I royally approve of this TL ! And I'm both overwhelmed and jealous that someone else is actually taking up this Borealian civilization idea, without ASB....

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Lands of Ice and Mice: An Alternate History of the Thule

- Thread starter DirtyCommie

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

I think it is also possible for the East Asian Eskimos to join this civilization giving it contact with China.

There are a lot of cultures between the Yupik and China...

On further reflection, a more extensive reply is warranted. As I understand it, the Yupik language spoken by so called 'Siberian Eskimo' who are around the Bering peninsula, is related to both the North American Alaskan 'Aleut' languages, and the more broadly extensive Inuit languages which range from Alaska to Greenland and Labrador.

It appears that Yupik diverged from the Aleut languages approximately 3000 years ago, and diverged from Inuit roughly 1000 year ago. This suggests to me that the Yupik were originally part of the proto-inuit group resident in Alaska (the Thule culture). Approximately 1000 years ago, that Thule culture began to expand out of its homeland, the group remaining or moving east across the Canadian Arctic and Greenland became the Inuit we know today. The group that moved west, re-crossing the Bering straight and colonizing Asia (for a change), lost contact and with isolation and contact/interbreeding/borrowing from other cultures, became the Yupik. Other groups such as the Chuchki were unrelated.

In this timeline, I don't think that the Yupik/Inuit split will be so thorough. What I envision is the Eastern Inuit developing Agriculture, and that this moves west, eventually into Alaska, and that there are further waves of migration from Alaska, which either swamp or merge with the Yupik culture (at this point, diverging only a couple of centuries) and basically butterflying them into Siberian resident Thule, and which add to the tools and package available, allowing the Siberian Thule to expand further along the Arctic and Pacific coasts. Sorry if this seems dry.

But despite this, the Siberian Thule are still a long way from China. Overland, they'd have to get through the Mongols, and north of the Mongols, other Siberian peoples. So there wouldn't be direct overland contact. There might be some occasional sea contact with Japan or Korea or Manchuria, which would amount to indirect contact with China. And there might even be something of a trading network establishing in the later era of the Thule civilization, say after 1500. But for the most part, the Thule would have the same sort of hazy notion of China that they have of Europe. Enough contact through peripheries to be aware that there are a lot of strange people in a strange land far away and hard to reach.

I'm not sure I envision a lot of cultural transfer from China/Manchuria/Korea/Japan, in part because I don't see these cultures having the same sort of 'in your face' interface that the Thule end up having with the Norse in Greenland. Even with Greenland, the cultural transfer, while significant, is far from comprehensive.

I hope that this helps.

On further reflection, a more extensive reply is warranted. As I understand it, the Yupik language spoken by so called 'Siberian Eskimo' who are around the Bering peninsula, is related to both the North American Alaskan 'Aleut' languages, and the more broadly extensive Inuit languages which range from Alaska to Greenland and Labrador.

It appears that Yupik diverged from the Aleut languages approximately 3000 years ago, and diverged from Inuit roughly 1000 year ago. This suggests to me that the Yupik were originally part of the proto-inuit group resident in Alaska (the Thule culture). Approximately 1000 years ago, that Thule culture began to expand out of its homeland, the group remaining or moving east across the Canadian Arctic and Greenland became the Inuit we know today. The group that moved west, re-crossing the Bering straight and colonizing Asia (for a change), lost contact and with isolation and contact/interbreeding/borrowing from other cultures, became the Yupik. Other groups such as the Chuchki were unrelated.

In this timeline, I don't think that the Yupik/Inuit split will be so thorough. What I envision is the Eastern Inuit developing Agriculture, and that this moves west, eventually into Alaska, and that there are further waves of migration from Alaska, which either swamp or merge with the Yupik culture (at this point, diverging only a couple of centuries) and basically butterflying them into Siberian resident Thule, and which add to the tools and package available, allowing the Siberian Thule to expand further along the Arctic and Pacific coasts. Sorry if this seems dry.

But despite this, the Siberian Thule are still a long way from China. Overland, they'd have to get through the Mongols, and north of the Mongols, other Siberian peoples. So there wouldn't be direct overland contact. There might be some occasional sea contact with Japan or Korea or Manchuria, which would amount to indirect contact with China. And there might even be something of a trading network establishing in the later era of the Thule civilization, say after 1500. But for the most part, the Thule would have the same sort of hazy notion of China that they have of Europe. Enough contact through peripheries to be aware that there are a lot of strange people in a strange land far away and hard to reach.

I'm not sure I envision a lot of cultural transfer from China/Manchuria/Korea/Japan, in part because I don't see these cultures having the same sort of 'in your face' interface that the Thule end up having with the Norse in Greenland. Even with Greenland, the cultural transfer, while significant, is far from comprehensive.

I hope that this helps.

Last edited:

On Lactose persistence (or tolerance), it is dominant, and there are two separate mutations that can cause it.

In the modern period 20% of Alaskan ethnic Inuit demonstrtae lactose persistence/tolerance. I don't know how many non-Inuit ancestors they modern population has, but that would suggest it wouldn't take that long to spread through a small population with a regular milk supply.

In the modern period 20% of Alaskan ethnic Inuit demonstrtae lactose persistence/tolerance. I don't know how many non-Inuit ancestors they modern population has, but that would suggest it wouldn't take that long to spread through a small population with a regular milk supply.

On Lactose persistence (or tolerance), it is dominant, and there are two separate mutations that can cause it.

In the modern period 20% of Alaskan ethnic Inuit demonstrtae lactose persistence/tolerance. I don't know how many non-Inuit ancestors they modern population has, but that would suggest it wouldn't take that long to spread through a small population with a regular milk supply.

Good to know. Thank you.

MY MOST AWESOME POSTS EVAH!!!

The Arctic is a harsh landscape. The territories have been repeatedly scoured by glaciers, the last of them retreating only some ten thousand years ago. In many areas, glacial action scoured the land down to raw bedrock. In other places, moving walls of ice picked up sands and gravel, depositing them in bands and eskers. Glacial melt basins pooled dust. Temperature extremes from summer to winter, water freezing and thawing, eroding winds and poor drainage have resulted in a landscape of rough soils, gravel and broken rock.

Winds are almost constant through the arctic. The wind dissipates heat readily, lowering overall temperatures. It also steals moisture, leaving a dry ‘arctic desert’ in many areas. Rainfall is infrequent, most of the water comes down as snow. In the Arctic Islands, precipitation is so sparse that the area is almost a desert. The driving wind picks up dust in the summer, ice crystals in the winter, both of which abrade tall plants like sandpaper. Unlike Siberia, the surrounding arctic ocean moderates temperatures, saving winters from the worst polar extremes, but also keeping summers cold, and making for late springs and early falls.

In many areas cold temperatures inhibit soil formation, slowing the decomposition of compost and plant material and reducing bacterial process to low levels. Biological processes cease completely in the cold winters. The result is a high organic matter content, but this biological wealth is slow to be released. River drainage, winds, extreme temperature fluctuations, the cycle of freeze and thaw, and groundwater and permafrost create a strange cryosoil. Go down a few feet, and you come to permafrost, perpetually and permanently frozen water saturating sandy soils and gravels.

Plants in the arctic have adapted to the conditions they find. Many arctic plants stay low, a low growing structure helps to avoid scouring by wind driven ice particles, while taking advantage of warm temperatures occurring at a thin boundary of almost still air close to the surface. Very few arctic plants reach any height. Two or three feet is tall for the Arctic, and most are shorter, many are much shorter. Both Roseroot and Sweetvetch reach an average height of a foot and a half. Claytonia is a fraction of that.

Many Arctic plants are like icebergs, with most of the plants mass hidden underground, and only a fraction above the surface. Claytonia is a classic example, a plant with a three foot root, that pokes a mere nine inches above ground. But Sweetvetch and Roseroot, and in fact many arctic plants share this quality - large root complexes which store energy and mass in order to get an early jumpstart on photosynthesis when its available.

Most arctic plants are perrenial, using longevity to ensure continuous presence when propagation is difficult and infrequent, and pacing growth out over two to ten seasons, maximizing their biological potential. Some are evergreen, maintaining leaves and stems to amortize biological production into the next year. Others like fireweed and roseoot will have leaves and stems which die off in fall, providing insulation and trapping moisture at the base of the plant.

Difficulty in propagation often means that plants of a species cluster closely together, forming clumps, matts and cushions. Dense growth of matts or cushions means more seed producing individuals, with more chance of propagating seeds. Clustering together means mutual shelter and maximizing the productive capacity of a given area.

These plants are extremely tolerant of freezing and dessication, not just in winter, but in other seasons, and thus are resistant to untimely frost events. They’re extremely tolerant of poor soils and low nutrients. There are subtle adaptations, leaves are often small, they can be hairy, or curl to trap little pockets of air to preserve warmth that would otherwise be stolen by direct exposure to wind. And of course, they share a capacity to begin growth almost immediately following snowmelt in the spring. Basically, they’re hardy opportunists, ready to take maximum advantage of the very short warm spells when they occur.

Despite these adaptations, there are large stretches of the arctic where it is little more than scoured rock and relic glaciers, a stony lifeless desert that you could mistake for the surface of Mars. There are immense rolling plains of tundra, exposed to wind, drained of moisture, warmth stolen away, sandblasted by ice and grit, which are basically lichens and moss, sparse and barren, where vegetation clings grimly to the landscape.

But the thing with life, is that it will find a way. There are a few advantages for Arctic plants. For instance, there’s sunlight. Lots of it. That far up the curvature of the earth, the intensity of sunlight is attenuated and often deflected by cloud cover, but over approximately 120 day growing season, sunlight can last anywhere from 18 hours a day all the way up to 24/7. That’s a lot of energy, and a lot of warmth accumulating.

For many plants, the name of the game is microclimates. How do you thrive when the wind steals away your warmth and water and scours your leaves?

Get out of the fucking wind. Get warm. Get more sun. These sound trite, but as noted, getting out of the wind is a universal strategy - that’s why arctic plants grow so low to the ground. Crevices, ditches, gullys, valleys, the sheltered side of hills all take plants out of the wind, and that makes a huge difference.

Without the wind, things can get very warm. Here’s an example: At Lake Hazen, on Ellesmere Island on 23 May 1958, surface soil temperatures as high as 21–24°C were recorded on a south-facing slope, the maximum open air temperature recorded was -5.6 C, essentially, the temperature at soil level was a full thirty degrees warmer than the open air. It would be a full two weeks before the open air temperature rose above freezing.

Ellesmere Island is about as close as you can get to the north pole, no joke. As you can see, biological strategies, or locations which get you out of the wind, get you a shot at a much warmer, biologically more productive environment. Warmer soils for longer periods are more biologically active, more organic matter is broken down into nutrients, soils become richer.

Of course, we’ve loaded the dice. That Ellesmere Island temperature was recorded on a south facing slope. The farther north you get, the more the inclination of the landscape affects the amount of light received. On Ellesmere Island a south-facing 30 degree slope receives about 15% more of the possible total solar radiation than a flat plane. Slopes facing other directions are at a disadvantage. For example, a steep north slope would receive less than half the sunlight received by that same flat plane we mentioned earlier.

At high latitudes, the sun remains at stable altitudes, rather than crossing the arch of the sky, which makes for stability under constant daylight and night time cooling is minimized or largely absent with the ground remaining warmer than the air throughout the summer. The results are that the frost-free growing season at ground surface level may be 3–4 weeks longer than open air temperatures would suggest.

If we can get microclimates like these as far north as Ellesmere Island, it becomes clear that its possible to magnify or maximize biological production in pockets of areas which would seem inescapably barren. It was the development and manipulation of microclimates which was the foundation of Arctic Agriculture technology, that marked the leap from a culture of relatively passive harvesters to one producing organized agricultural surpluses.

The specific location where Thule Agriculture first began is a matter of controversy. Favoured sites include the McKenzie Bay, Baffin Island or the Hudson Bay coast. All of these areas show archeological traces indicating systematic cultivation during the period 1170 - 1240. Due to intervening distances, however, it is considered extremely unlikely that one site’s development spread to the other sites.

Indeed, it is now believed that Agriculture may have emerged spontaneously, independently in several different locations, from a fairly uniform underlying cultural strata. To put it another way, a vast part of the Thule range had reached such an advanced state of pre-agricultural root propagation and harvest that many areas were able to take the next step on their own. In this interpretation, which specific area technically came first is largely academic. Agriculture spread from multiple points, and literally bootstrapped itself into existence.

Another view is that continuing expansion of territory and food resources drove a slow population explosion, which pushed the Thule into a malthusian crisis, which forced the development of agriculture in different areas.

Still another approach suggests that there was an additional common feature. The Thule expansion from their Alaskan Homeland, across the Arctic seems to coincide, at least initially, with the Medieval Warm Period, which endured from 800 to 1250. At least one theory suggests that the warm period produced a proliferation of fish and wildlife which triggered Thule overpopulation and waves of outward migration and expansion.

The end of the Medieval Warm period seems to coincide with the development of Thule Agriculture. Worsening or cooling climactic conditions had a double impact. Cooling had a negative impact on the animal populations that formed the backbone of the diet, forcing the Thule to rely much more heavily on plant harvest.

Cooling also impacted the plant harvest itself, both the range and quality of naturally occurring vegetation, forcing the Thule to adapt by aggressively maximizing their pre-agricultural harvest and propagation techniques, and wielding them into an agricultural package.

The early phase of the Agricultural revolution was simply a consolidation and expansion of existing techniques. With game declining from year to year, and average temperatures dropping, the Thule responded the way people always respond - by increasing effort. This meant more hunting, and hunting over larger areas, more intense hunting of previously overlooked or undesired species.

It also meant more intensive plant harvesting. This included more intensive and systematic harvesting of edible plants which hadn’t up to this time been a critical part of diet. But as conditions worsened, fewer and fewer food sources could be passed up. Berries, stems, leaves were scoured. Much more attention was paid to these plants, and their share of diet increased.

More intensive harvesting also included plants, especially the root staples, sweetvetch, claytonia and roseroot. But there came bottlenecks. There was visibly less to be gained by harvesting immature plants, and the harvesters knew it. It was understood that premature harvesting would result in a reduced yield now, and a much diminished yield in the future. So excess harvesting pressure was frowned upon.

Instead the increased effort was directed to planting and propagation. In Alaska, planting and propagation had been limited to existing patches, and sweetvetch and claytonia had spread gradually and naturally from there over time. Out in the lands we know as the Canadian north, this habit had morphed to planting and propagation in likely areas believed to contain favourable spirits, which had over time resulted in the plants becoming widespread.

Now with fewer and fewer options, planting effort intensified, and planting took place in any habitat that seemed suitable. Inevitably, the Thule outran primary plant habitat, attempting to maximize the distribution of their root crops. The result of course was planting effort in places where the root crops fared poorly or did not take at all.

Now, this is the critical point. It is possible that the Thule cultivation effort would stop there, and we would have simply seen some incremental adjustments in the plants range, and a continuation of hunter gatherer society. The Agricultural revolution might never have taken place.

But Thule culture had, for want of a better phrase, developed a pattern of active negotiation with the spirits. This had begun with replanting root bits when harvesting. It had extended to planting seeds and root sections in new areas, and tacit agreements with the spirits to harvest later, an agreement that included the commitment to wait to return. But the cultural traits had continued to elaborate, Sweetvetch grew readily, but both Roseroot and Claytonia required more care and attention in propagation, there had been an evolving tradition in planting or transplanting these, of taking more measures, and taking specific measures to protect the plants. The accumulated cultural wisdom was that the spirits could be finicky, but also that they could be propitiated, that they could be jollied along.

So, as Sweetvetch, Claytonia and Roseroot plantings were extended beyond their prime habitat, they did poorly. This was obviously because the spirits were unhappy. The question was what was required to make them happier. By this time, culture had accumulated a significant amount of information and insight, and the effects of wind exposure or lack of water were intuitively grasped.

This triggered Shaman-lead communal labour efforts to please the earth spirits. Earth and gravel were mounded to form wind breaks, which had the effect of allowing local temperatures on the other side of the windbreak to build up. Shallow trenches were dug or scooped to create warm recessed habitat, or make permafrost more accessible. It’s difficult to say to what extent these practices were motivated by direct cause and effect, far more likely was the sentiment that these actions encouraged goodwill from the spirits. But the effect was that vegetation grew faster and thrived more visibly.

More banked mounds were built up or reshaped to form ‘snow catchers’, places that drifting snow would build up into banks, providing critical moisture. Mounds were extended in both directions, forming long lines which curved, bent, looped or formed angles. Mound lines were generally small, often no more than a couple of feet in height, the tallest might be five or six feet.

To maximize wind protection and moisture accumulation, mound lines were built in succession, one after the other.

On the protected sides of mound lines, shallow trenches were dug to create warmer recessed plant habitat. Between mound lines, narrower and deeper trenches drained land or facilitated irrigation, sometimes moving water in or out of carefully selected gaps. Drainage and irrigation became more elaborate and ambitious. Earthworks were raised to shield against and store floodwaters for later use. Heavy snow cover was ponded during melt season and drained. Trenches were dug into permafrost to release local water. Irrigation channels were used to divert water from rivers and streams.

Mound construction was often a matter of trial and error, as the builders searched for the best locations and designs to block the arctic wind or gather snow and water. These communal labour efforts were small scale, carried on at the level of clans or groups, involving no more than a handful of individuals at a time, and using traditional digging/harvesting tools. But they were significant, and they were cumulative, year after year. The different pioneer agricultural complexes all evolved their own mound techniques and shapes, but each of them independently developed their own mound and trench techniques.

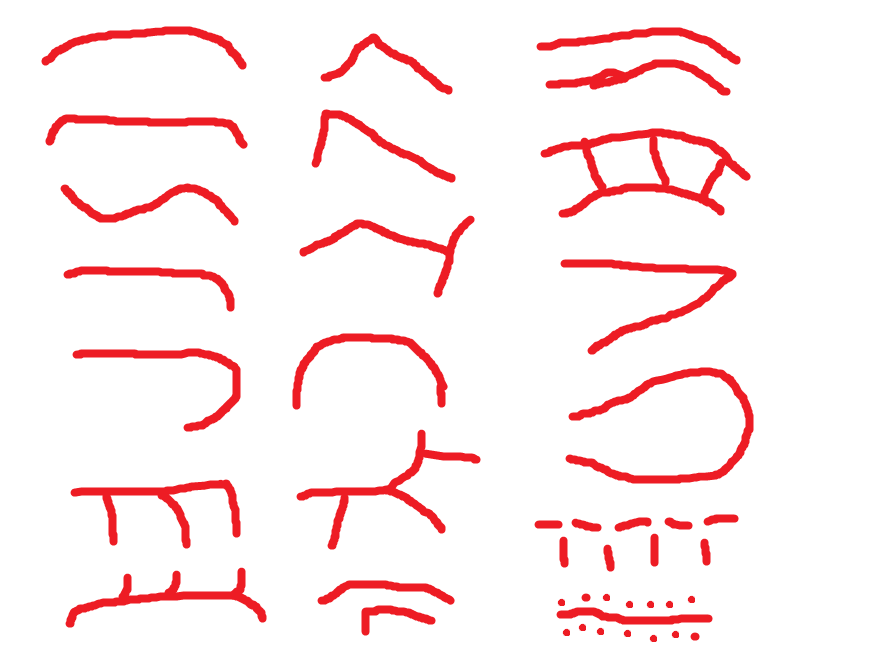

[Fig c.1. Types of Thule Mound lines. Taken from the Journals of Kenneth Malt, a British diplomat who travelled extensively through Thule lands, 1752-1756, and made numerous sketches. Malt was particularly interested in northern agriculture and landforms, and his sketchbooks and journals are considered to be landmark works in Thule studies. This drawing depicts the various styles of mound shapes that Malt encountered.]

The Arctic is a harsh landscape. The territories have been repeatedly scoured by glaciers, the last of them retreating only some ten thousand years ago. In many areas, glacial action scoured the land down to raw bedrock. In other places, moving walls of ice picked up sands and gravel, depositing them in bands and eskers. Glacial melt basins pooled dust. Temperature extremes from summer to winter, water freezing and thawing, eroding winds and poor drainage have resulted in a landscape of rough soils, gravel and broken rock.

Winds are almost constant through the arctic. The wind dissipates heat readily, lowering overall temperatures. It also steals moisture, leaving a dry ‘arctic desert’ in many areas. Rainfall is infrequent, most of the water comes down as snow. In the Arctic Islands, precipitation is so sparse that the area is almost a desert. The driving wind picks up dust in the summer, ice crystals in the winter, both of which abrade tall plants like sandpaper. Unlike Siberia, the surrounding arctic ocean moderates temperatures, saving winters from the worst polar extremes, but also keeping summers cold, and making for late springs and early falls.

In many areas cold temperatures inhibit soil formation, slowing the decomposition of compost and plant material and reducing bacterial process to low levels. Biological processes cease completely in the cold winters. The result is a high organic matter content, but this biological wealth is slow to be released. River drainage, winds, extreme temperature fluctuations, the cycle of freeze and thaw, and groundwater and permafrost create a strange cryosoil. Go down a few feet, and you come to permafrost, perpetually and permanently frozen water saturating sandy soils and gravels.

Plants in the arctic have adapted to the conditions they find. Many arctic plants stay low, a low growing structure helps to avoid scouring by wind driven ice particles, while taking advantage of warm temperatures occurring at a thin boundary of almost still air close to the surface. Very few arctic plants reach any height. Two or three feet is tall for the Arctic, and most are shorter, many are much shorter. Both Roseroot and Sweetvetch reach an average height of a foot and a half. Claytonia is a fraction of that.

Many Arctic plants are like icebergs, with most of the plants mass hidden underground, and only a fraction above the surface. Claytonia is a classic example, a plant with a three foot root, that pokes a mere nine inches above ground. But Sweetvetch and Roseroot, and in fact many arctic plants share this quality - large root complexes which store energy and mass in order to get an early jumpstart on photosynthesis when its available.

Most arctic plants are perrenial, using longevity to ensure continuous presence when propagation is difficult and infrequent, and pacing growth out over two to ten seasons, maximizing their biological potential. Some are evergreen, maintaining leaves and stems to amortize biological production into the next year. Others like fireweed and roseoot will have leaves and stems which die off in fall, providing insulation and trapping moisture at the base of the plant.

Difficulty in propagation often means that plants of a species cluster closely together, forming clumps, matts and cushions. Dense growth of matts or cushions means more seed producing individuals, with more chance of propagating seeds. Clustering together means mutual shelter and maximizing the productive capacity of a given area.

These plants are extremely tolerant of freezing and dessication, not just in winter, but in other seasons, and thus are resistant to untimely frost events. They’re extremely tolerant of poor soils and low nutrients. There are subtle adaptations, leaves are often small, they can be hairy, or curl to trap little pockets of air to preserve warmth that would otherwise be stolen by direct exposure to wind. And of course, they share a capacity to begin growth almost immediately following snowmelt in the spring. Basically, they’re hardy opportunists, ready to take maximum advantage of the very short warm spells when they occur.

Despite these adaptations, there are large stretches of the arctic where it is little more than scoured rock and relic glaciers, a stony lifeless desert that you could mistake for the surface of Mars. There are immense rolling plains of tundra, exposed to wind, drained of moisture, warmth stolen away, sandblasted by ice and grit, which are basically lichens and moss, sparse and barren, where vegetation clings grimly to the landscape.

But the thing with life, is that it will find a way. There are a few advantages for Arctic plants. For instance, there’s sunlight. Lots of it. That far up the curvature of the earth, the intensity of sunlight is attenuated and often deflected by cloud cover, but over approximately 120 day growing season, sunlight can last anywhere from 18 hours a day all the way up to 24/7. That’s a lot of energy, and a lot of warmth accumulating.

For many plants, the name of the game is microclimates. How do you thrive when the wind steals away your warmth and water and scours your leaves?

Get out of the fucking wind. Get warm. Get more sun. These sound trite, but as noted, getting out of the wind is a universal strategy - that’s why arctic plants grow so low to the ground. Crevices, ditches, gullys, valleys, the sheltered side of hills all take plants out of the wind, and that makes a huge difference.

Without the wind, things can get very warm. Here’s an example: At Lake Hazen, on Ellesmere Island on 23 May 1958, surface soil temperatures as high as 21–24°C were recorded on a south-facing slope, the maximum open air temperature recorded was -5.6 C, essentially, the temperature at soil level was a full thirty degrees warmer than the open air. It would be a full two weeks before the open air temperature rose above freezing.

Ellesmere Island is about as close as you can get to the north pole, no joke. As you can see, biological strategies, or locations which get you out of the wind, get you a shot at a much warmer, biologically more productive environment. Warmer soils for longer periods are more biologically active, more organic matter is broken down into nutrients, soils become richer.

Of course, we’ve loaded the dice. That Ellesmere Island temperature was recorded on a south facing slope. The farther north you get, the more the inclination of the landscape affects the amount of light received. On Ellesmere Island a south-facing 30 degree slope receives about 15% more of the possible total solar radiation than a flat plane. Slopes facing other directions are at a disadvantage. For example, a steep north slope would receive less than half the sunlight received by that same flat plane we mentioned earlier.

At high latitudes, the sun remains at stable altitudes, rather than crossing the arch of the sky, which makes for stability under constant daylight and night time cooling is minimized or largely absent with the ground remaining warmer than the air throughout the summer. The results are that the frost-free growing season at ground surface level may be 3–4 weeks longer than open air temperatures would suggest.

If we can get microclimates like these as far north as Ellesmere Island, it becomes clear that its possible to magnify or maximize biological production in pockets of areas which would seem inescapably barren. It was the development and manipulation of microclimates which was the foundation of Arctic Agriculture technology, that marked the leap from a culture of relatively passive harvesters to one producing organized agricultural surpluses.

The specific location where Thule Agriculture first began is a matter of controversy. Favoured sites include the McKenzie Bay, Baffin Island or the Hudson Bay coast. All of these areas show archeological traces indicating systematic cultivation during the period 1170 - 1240. Due to intervening distances, however, it is considered extremely unlikely that one site’s development spread to the other sites.

Indeed, it is now believed that Agriculture may have emerged spontaneously, independently in several different locations, from a fairly uniform underlying cultural strata. To put it another way, a vast part of the Thule range had reached such an advanced state of pre-agricultural root propagation and harvest that many areas were able to take the next step on their own. In this interpretation, which specific area technically came first is largely academic. Agriculture spread from multiple points, and literally bootstrapped itself into existence.

Another view is that continuing expansion of territory and food resources drove a slow population explosion, which pushed the Thule into a malthusian crisis, which forced the development of agriculture in different areas.

Still another approach suggests that there was an additional common feature. The Thule expansion from their Alaskan Homeland, across the Arctic seems to coincide, at least initially, with the Medieval Warm Period, which endured from 800 to 1250. At least one theory suggests that the warm period produced a proliferation of fish and wildlife which triggered Thule overpopulation and waves of outward migration and expansion.

The end of the Medieval Warm period seems to coincide with the development of Thule Agriculture. Worsening or cooling climactic conditions had a double impact. Cooling had a negative impact on the animal populations that formed the backbone of the diet, forcing the Thule to rely much more heavily on plant harvest.

Cooling also impacted the plant harvest itself, both the range and quality of naturally occurring vegetation, forcing the Thule to adapt by aggressively maximizing their pre-agricultural harvest and propagation techniques, and wielding them into an agricultural package.

The early phase of the Agricultural revolution was simply a consolidation and expansion of existing techniques. With game declining from year to year, and average temperatures dropping, the Thule responded the way people always respond - by increasing effort. This meant more hunting, and hunting over larger areas, more intense hunting of previously overlooked or undesired species.

It also meant more intensive plant harvesting. This included more intensive and systematic harvesting of edible plants which hadn’t up to this time been a critical part of diet. But as conditions worsened, fewer and fewer food sources could be passed up. Berries, stems, leaves were scoured. Much more attention was paid to these plants, and their share of diet increased.

More intensive harvesting also included plants, especially the root staples, sweetvetch, claytonia and roseroot. But there came bottlenecks. There was visibly less to be gained by harvesting immature plants, and the harvesters knew it. It was understood that premature harvesting would result in a reduced yield now, and a much diminished yield in the future. So excess harvesting pressure was frowned upon.

Instead the increased effort was directed to planting and propagation. In Alaska, planting and propagation had been limited to existing patches, and sweetvetch and claytonia had spread gradually and naturally from there over time. Out in the lands we know as the Canadian north, this habit had morphed to planting and propagation in likely areas believed to contain favourable spirits, which had over time resulted in the plants becoming widespread.

Now with fewer and fewer options, planting effort intensified, and planting took place in any habitat that seemed suitable. Inevitably, the Thule outran primary plant habitat, attempting to maximize the distribution of their root crops. The result of course was planting effort in places where the root crops fared poorly or did not take at all.

Now, this is the critical point. It is possible that the Thule cultivation effort would stop there, and we would have simply seen some incremental adjustments in the plants range, and a continuation of hunter gatherer society. The Agricultural revolution might never have taken place.

But Thule culture had, for want of a better phrase, developed a pattern of active negotiation with the spirits. This had begun with replanting root bits when harvesting. It had extended to planting seeds and root sections in new areas, and tacit agreements with the spirits to harvest later, an agreement that included the commitment to wait to return. But the cultural traits had continued to elaborate, Sweetvetch grew readily, but both Roseroot and Claytonia required more care and attention in propagation, there had been an evolving tradition in planting or transplanting these, of taking more measures, and taking specific measures to protect the plants. The accumulated cultural wisdom was that the spirits could be finicky, but also that they could be propitiated, that they could be jollied along.

So, as Sweetvetch, Claytonia and Roseroot plantings were extended beyond their prime habitat, they did poorly. This was obviously because the spirits were unhappy. The question was what was required to make them happier. By this time, culture had accumulated a significant amount of information and insight, and the effects of wind exposure or lack of water were intuitively grasped.

This triggered Shaman-lead communal labour efforts to please the earth spirits. Earth and gravel were mounded to form wind breaks, which had the effect of allowing local temperatures on the other side of the windbreak to build up. Shallow trenches were dug or scooped to create warm recessed habitat, or make permafrost more accessible. It’s difficult to say to what extent these practices were motivated by direct cause and effect, far more likely was the sentiment that these actions encouraged goodwill from the spirits. But the effect was that vegetation grew faster and thrived more visibly.

More banked mounds were built up or reshaped to form ‘snow catchers’, places that drifting snow would build up into banks, providing critical moisture. Mounds were extended in both directions, forming long lines which curved, bent, looped or formed angles. Mound lines were generally small, often no more than a couple of feet in height, the tallest might be five or six feet.

To maximize wind protection and moisture accumulation, mound lines were built in succession, one after the other.

On the protected sides of mound lines, shallow trenches were dug to create warmer recessed plant habitat. Between mound lines, narrower and deeper trenches drained land or facilitated irrigation, sometimes moving water in or out of carefully selected gaps. Drainage and irrigation became more elaborate and ambitious. Earthworks were raised to shield against and store floodwaters for later use. Heavy snow cover was ponded during melt season and drained. Trenches were dug into permafrost to release local water. Irrigation channels were used to divert water from rivers and streams.

Mound construction was often a matter of trial and error, as the builders searched for the best locations and designs to block the arctic wind or gather snow and water. These communal labour efforts were small scale, carried on at the level of clans or groups, involving no more than a handful of individuals at a time, and using traditional digging/harvesting tools. But they were significant, and they were cumulative, year after year. The different pioneer agricultural complexes all evolved their own mound techniques and shapes, but each of them independently developed their own mound and trench techniques.

[Fig c.1. Types of Thule Mound lines. Taken from the Journals of Kenneth Malt, a British diplomat who travelled extensively through Thule lands, 1752-1756, and made numerous sketches. Malt was particularly interested in northern agriculture and landforms, and his sketchbooks and journals are considered to be landmark works in Thule studies. This drawing depicts the various styles of mound shapes that Malt encountered.]

Over time, we see a rapid increase in sophistication and technique. Mound lines and water trench networks became larger and more complex in design, manipulating surface topography, to create large low wind or still air areas. All of these works were relatively small scale, but they were effective, they were taking place collectively over vast areas, and they were cumulative.

Thule moundbuilding and microclimate engineering turned inward, into the fertile fields, enhancing productivity, and ranged ever outward, always attempting to placate or encourage the spirits. Decade after decade, the mound and microclimate networks expanded ever outward.

There were other key innovations. The Shamans of Thule culture became very adept at recognizing the different intensities and amounts of light available to different orientations and angles of slopes. This was a kind of practical feng shui that had real applications with respect to sunlight, warmth, wind and water. Shamans often provided expert though intuitive direction with respect to which field and slopes to cultivate, how they were to be cultivated, where windbreak mounds and water trenches were to be created.

Another critical development was the practice of ‘smudge-burning’ new fields. This was not equivalent to slash and burn agriculture. Rather, arctic soils often contained high proportions of ‘raw’ organic matter. Smudge burning was used to raise local temperatures enough to promote a burst of bacterial decay, unlocking dormant soil fertility, and kicking arctic soils up to a higher level of productivity and richness. This was often done in early spring, before thaw, to avoid unnecessarily robbing the soil of water.

Another form of ‘smudge burning’ in late winter or early spring, involved burning lichens in fields to produce a slow smoldering fire that generated a thick black oily smoke. This smoke would darken the snow cover as the weather warmed, retaining heat and accelerating snow melt. Sometimes the ‘smudge fire’ was centrally located, sometimes a shaman would walk a swinging brazier through the field. Similar practices included spreading ashes, dust, or gathered shredded lichen and moss. The purpose was a sort of magical blessing, but the real effect was to hasten snowmelt and allow plants to become active earlier.

Stone cover agriculture was also developed, covering soils with small stones to reduce soil evaporation and build and retain heat. Stone cover tended to increase the overall warmth of the underlying soil, since they accumulated and dispersed heat slowly. In other areas, moss cover was used for similar effects.

Another innovation was the near simultaneous adoption of an additional suite of plants. Fireweed, Bistort, Plantain, Rhubarb and Ragwort were all rapidly added to the agricultural package. These plants were characterized by edible leaves and stems, less nutritious and less valuable than the three gifts, they had two strong advantages - they were easily cultivated and readily adopted by the techniques of root crop agriculture and their harvest periods did not overlap but complemented the root crops - they were best harvested either before or after the root crops and thus available labour could be used.

As the Agricultural package matured over the next few centuries, berry crops were added, regional domesticates from Alaska, Labrador and Greenland were added, and new domesticated animals for food and labour were added to the mix.

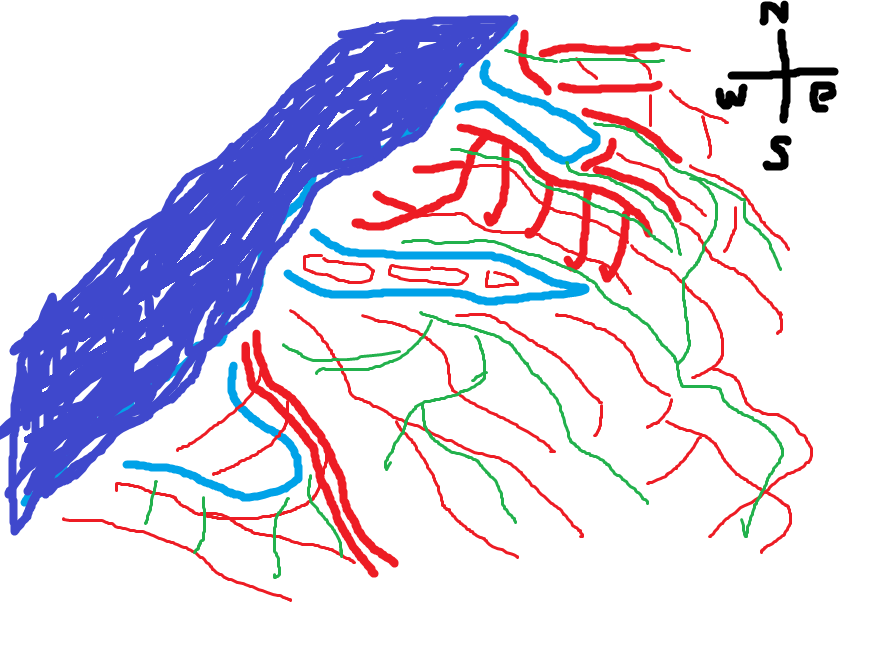

[fic c.13. Mound Construction on the Copper River tributary. Original drawing by Kenneth Malt, 1753. Colour added in 1932, Brittanica edition. The Copper River tributary is rendered in deep blue. Thick red lines indicate the major mound erections, reaching up to twelve feet in height. Thin red lines indicate smaller mound construction, from two to four feet in height. Thin green lines refer to water trenches. The thick light blue lines appear to depict river flood ponding structures. It is estimated that the Mound and Trench complex depicted, represents 200 to 300 years of cumulative local development.]

Thule moundbuilding and microclimate engineering turned inward, into the fertile fields, enhancing productivity, and ranged ever outward, always attempting to placate or encourage the spirits. Decade after decade, the mound and microclimate networks expanded ever outward.

There were other key innovations. The Shamans of Thule culture became very adept at recognizing the different intensities and amounts of light available to different orientations and angles of slopes. This was a kind of practical feng shui that had real applications with respect to sunlight, warmth, wind and water. Shamans often provided expert though intuitive direction with respect to which field and slopes to cultivate, how they were to be cultivated, where windbreak mounds and water trenches were to be created.

Another critical development was the practice of ‘smudge-burning’ new fields. This was not equivalent to slash and burn agriculture. Rather, arctic soils often contained high proportions of ‘raw’ organic matter. Smudge burning was used to raise local temperatures enough to promote a burst of bacterial decay, unlocking dormant soil fertility, and kicking arctic soils up to a higher level of productivity and richness. This was often done in early spring, before thaw, to avoid unnecessarily robbing the soil of water.

Another form of ‘smudge burning’ in late winter or early spring, involved burning lichens in fields to produce a slow smoldering fire that generated a thick black oily smoke. This smoke would darken the snow cover as the weather warmed, retaining heat and accelerating snow melt. Sometimes the ‘smudge fire’ was centrally located, sometimes a shaman would walk a swinging brazier through the field. Similar practices included spreading ashes, dust, or gathered shredded lichen and moss. The purpose was a sort of magical blessing, but the real effect was to hasten snowmelt and allow plants to become active earlier.

Stone cover agriculture was also developed, covering soils with small stones to reduce soil evaporation and build and retain heat. Stone cover tended to increase the overall warmth of the underlying soil, since they accumulated and dispersed heat slowly. In other areas, moss cover was used for similar effects.

Another innovation was the near simultaneous adoption of an additional suite of plants. Fireweed, Bistort, Plantain, Rhubarb and Ragwort were all rapidly added to the agricultural package. These plants were characterized by edible leaves and stems, less nutritious and less valuable than the three gifts, they had two strong advantages - they were easily cultivated and readily adopted by the techniques of root crop agriculture and their harvest periods did not overlap but complemented the root crops - they were best harvested either before or after the root crops and thus available labour could be used.

As the Agricultural package matured over the next few centuries, berry crops were added, regional domesticates from Alaska, Labrador and Greenland were added, and new domesticated animals for food and labour were added to the mix.

[fic c.13. Mound Construction on the Copper River tributary. Original drawing by Kenneth Malt, 1753. Colour added in 1932, Brittanica edition. The Copper River tributary is rendered in deep blue. Thick red lines indicate the major mound erections, reaching up to twelve feet in height. Thin red lines indicate smaller mound construction, from two to four feet in height. Thin green lines refer to water trenches. The thick light blue lines appear to depict river flood ponding structures. It is estimated that the Mound and Trench complex depicted, represents 200 to 300 years of cumulative local development.]

The rapidly emerging agricultural package had strengths and weaknesses. The primary weakness was the perrenial nature of just about all the Thule crops. Where a southern agricultural package would turn in a crop in the same year it was planted, the Thule package took anywhere from two to four years for plants to mature. Generally, Thule agriculture followed a three year/three field model. Only a third of fields were harvested in any particular year.

As agriculture grew more complex, fields tended to be harvested uniformly, so the majority plants in a field would tend to be the same age cohort. Elaborate markers were used to identify the fields, and particularly the age of the cohort.

In practical terms, this meant that on average, Thule crops were a third or a quarter as productive as comparable European crops. While this placed an upper limit on population in comparison to southern cultures, it still allowed an immense population in comparison to hunter-gatherer levels.

The greater volume of cropland under cultivation, in comparison to yield, also meant that Thule agriculture was significantly more labour intensive than southern agriculture. However, this was mostly offset by a couple of factors.

First, most Thule crops grew readily on their own, as befits pioneer species which clustered readily, so they didn’t require nearly the degree of cultivation attention. Southern crops were often delicate. Thule crops were anything but.

Second, Thule crops simply lacked the challengers of Southern crops. A significant portion of southern energy had to be devoted to weeding and eradicating rival species. In contrast, Arctic plants had a lot of difficulty propagating, and in the situation of wind break microclimates, even more difficulty. Thule crops tended to be relatively weed free, as well as mostly free of parasites, fungus, insects, etc.

The result was that although Thule crops required far more area for a given consistent annual harvest, the crops themselves were extremely low maintenance, minimizing the labour investment. This allowed for redeployment of labour into environmental manipulation, which, as we’ve noted, is cumulative rather than annual.

Thule agriculture, emerging in each of its three founding locations, expanded steadily through the north. The initial phase saw Mackenzie basin expanding east and south, Hudson Bay expanding north and west, and Baffin Island expanding south and to the islands. During this period, expansion was incremental, and Thule polities were insignificant.

Between 1240 and roughly 1350, the movement of different agricultural complexes was charted by the different styles of mound buildings, and different unique secondary cultivars particular to each. But as the agricultural territories overlapped, each adopted mound styles and secondary cultivars from the others.

By 1375, the portfolio of agricultural techniques and secondary plants had been fully exchanged and it was effectively impossible in most areas to trace the originating subculture. The period between 1200 and 1350 is known as the 'First Thule Agricultural Period.'

What is known as the 'Second Thule Agricultural Period', generally considered to be 1350 to 1550, marked the expansion of Thule Agriculture East, North and West.

From Baffin Island, there was a southern expansion into the Newfoundland and Labrador north region. Sometimes considered the last phase of the First Period, the Newfoundland and Labrador region retained an archaic Baffin Island complex, with many of the secondary cultivars missing, or being introduced very slowly. The Quebec/Labrador complex remained historically isolated and backward, but did contribute Labrador tea.

Meanwhile, the Baffin Island complex expanded north, entering Greenland and eventually encountering the Norse settlements. Trade and communication was more active with Greenland than Quebec/Labrador, and more of the full aggregate Agricultural package was received. In turn, Greenland provided Kuva, an indigenous crop, and acquired European root vegetables, notably carrots and onions.

In the west, the originating Thule culture of Alaska was resistant to importing agriculture, but eventually acquired it. The resulting population expansion produced a new wave of immigration to Asia, carrying the agricultural package with it.

The Thule revolution produced profound changes, the composition of the northern landscape was changing dramatically. Places were going green that had previously been barren. Marginal landscapes were now far more productive than ever before. The Arctic landscape was transforming. A neolithic people were literally terraforming one of the most inhospitable regions of earth.

[fic c.31. The expansion of the Thule Agricultural revolutions. Thick green areas depict the original sites of Thule Agriculture. The arrows depict routes of expansion, up to the limits of the First Period, circa 1200 - 1350, bordered in green. The areas bordered in blue depict the agreed areas of the Second Period.]

As agriculture grew more complex, fields tended to be harvested uniformly, so the majority plants in a field would tend to be the same age cohort. Elaborate markers were used to identify the fields, and particularly the age of the cohort.

In practical terms, this meant that on average, Thule crops were a third or a quarter as productive as comparable European crops. While this placed an upper limit on population in comparison to southern cultures, it still allowed an immense population in comparison to hunter-gatherer levels.

The greater volume of cropland under cultivation, in comparison to yield, also meant that Thule agriculture was significantly more labour intensive than southern agriculture. However, this was mostly offset by a couple of factors.

First, most Thule crops grew readily on their own, as befits pioneer species which clustered readily, so they didn’t require nearly the degree of cultivation attention. Southern crops were often delicate. Thule crops were anything but.

Second, Thule crops simply lacked the challengers of Southern crops. A significant portion of southern energy had to be devoted to weeding and eradicating rival species. In contrast, Arctic plants had a lot of difficulty propagating, and in the situation of wind break microclimates, even more difficulty. Thule crops tended to be relatively weed free, as well as mostly free of parasites, fungus, insects, etc.

The result was that although Thule crops required far more area for a given consistent annual harvest, the crops themselves were extremely low maintenance, minimizing the labour investment. This allowed for redeployment of labour into environmental manipulation, which, as we’ve noted, is cumulative rather than annual.

Thule agriculture, emerging in each of its three founding locations, expanded steadily through the north. The initial phase saw Mackenzie basin expanding east and south, Hudson Bay expanding north and west, and Baffin Island expanding south and to the islands. During this period, expansion was incremental, and Thule polities were insignificant.

Between 1240 and roughly 1350, the movement of different agricultural complexes was charted by the different styles of mound buildings, and different unique secondary cultivars particular to each. But as the agricultural territories overlapped, each adopted mound styles and secondary cultivars from the others.

By 1375, the portfolio of agricultural techniques and secondary plants had been fully exchanged and it was effectively impossible in most areas to trace the originating subculture. The period between 1200 and 1350 is known as the 'First Thule Agricultural Period.'

What is known as the 'Second Thule Agricultural Period', generally considered to be 1350 to 1550, marked the expansion of Thule Agriculture East, North and West.

From Baffin Island, there was a southern expansion into the Newfoundland and Labrador north region. Sometimes considered the last phase of the First Period, the Newfoundland and Labrador region retained an archaic Baffin Island complex, with many of the secondary cultivars missing, or being introduced very slowly. The Quebec/Labrador complex remained historically isolated and backward, but did contribute Labrador tea.

Meanwhile, the Baffin Island complex expanded north, entering Greenland and eventually encountering the Norse settlements. Trade and communication was more active with Greenland than Quebec/Labrador, and more of the full aggregate Agricultural package was received. In turn, Greenland provided Kuva, an indigenous crop, and acquired European root vegetables, notably carrots and onions.

In the west, the originating Thule culture of Alaska was resistant to importing agriculture, but eventually acquired it. The resulting population expansion produced a new wave of immigration to Asia, carrying the agricultural package with it.

The Thule revolution produced profound changes, the composition of the northern landscape was changing dramatically. Places were going green that had previously been barren. Marginal landscapes were now far more productive than ever before. The Arctic landscape was transforming. A neolithic people were literally terraforming one of the most inhospitable regions of earth.

[fic c.31. The expansion of the Thule Agricultural revolutions. Thick green areas depict the original sites of Thule Agriculture. The arrows depict routes of expansion, up to the limits of the First Period, circa 1200 - 1350, bordered in green. The areas bordered in blue depict the agreed areas of the Second Period.]

What's the red line on the last map? Major transport route or what?

A climate boundary. Above it, you get the low precipitation Islands.

My next post will be a survey of the secondary plant cultivars or domesticates of the First Thule Agricultural period. Basically, how and why these plants came to be part of the agricultural package, their reproduction and growing qualities, habitat preferences, food value, harvest times, point of origin and vector of spread.

Initially, there wasn't much, if any, protein in the agricultural package. In the first generations, the Thule diet shifted predominantly to plants, with intensive hunting and fishing effort on wildlife. The only significant domesticate was the Dog, whose numbers diminished rapidly, both as a proportion of the human population, and in real terms as it had to compete with humans for more of its food supply.

It's only after the Agricultural revolution is under way that we see the domestication of the Caribou and shortly thereafter the Musk Ox, and I have a couple of posts in development which will explore the acquisition of the big draft animals and their effects on Thule culture and diet.

Initially, there wasn't much, if any, protein in the agricultural package. In the first generations, the Thule diet shifted predominantly to plants, with intensive hunting and fishing effort on wildlife. The only significant domesticate was the Dog, whose numbers diminished rapidly, both as a proportion of the human population, and in real terms as it had to compete with humans for more of its food supply.

It's only after the Agricultural revolution is under way that we see the domestication of the Caribou and shortly thereafter the Musk Ox, and I have a couple of posts in development which will explore the acquisition of the big draft animals and their effects on Thule culture and diet.

The Three Lesser Gifts - Secondary Cultivation in the Thule First Agricultural Period

The Thule planting and harvest culture venerated threes. There were the ‘Three Gifts’ of Sweetveetch, Claytonia and Roseroot. There were the ‘Three Years’ harvest period, the ‘Three fields’ system of rotating harvest. Thule Shamans identified the ‘Three Good Seasons’ for harvest, and the ‘Three Good Directions’ for planting slopes - south, east, west.

Early in the Agricultural revolution, new cultivars were added to the ‘Three Gifts’ generally known as the ‘Three Lesser Gifts’ although technically there were five or six of them in all, when the collective contributions of the three originating agricultural complexes were added together.

These were in no way brand new plants. Rather, they had all been regularly, if sometimes intermittently harvested by the Thule culture These plants differed significantly from the Three Gifts in key ways.

Unlike the Three Gifts, these cultivars for the most part were not subject to pre-agricultural practices. They were harvested where they grew, but there was little effective effort to thank the spirits. The habit of replanting root cuttings was absent. There was no effort to propagate the plants to new habitats or fields, as with Sweetvetch and later Claytonia and Roseroot. There was no particular effort to encourage their growth, as with Roseroot or Claytonia by careful planting or adjustments to local conditions. They were simply picked where they were found at appropriate seasons, and any gifts made to the spirits were usually not ones that produced significant effects.

The new cultivars differed from the old ones in that mostly rather than producing edible roots, they generated edible leafs and stems. Nutritionally, they were much less essential, and had overall less nutrition, than the root plants, but still had some genuine significance. In the hunter/gatherer phase, they had minimal significance, and all else being equal would never have amounted to any substantial part of the Thule diet.

On the other hand, they shared some key features with the root crops. They were all flowering perrenials, which took two to four years. Most of them were pioneer species like Sweetvetch, hardy opportunists adept at taking root in and colonizing disturbed or stripped down environments. Most could and would reproduce vegetatively. And all of them were of the hardy arctic variety, adapted to poor soils, harsh conditions.

The harvest of the Root crops tended to encourage the harvesting of other edible plants in the area. Essentially, if the Thule were making the investment to remain in certain areas a little longer to dig up Sweetvetch and Claytonia, it made sense to use any spare time to catch or harvest whatever else the local area offered. So these plants tended to be harvested with increasing frequency and became more significant as the importance of the root plants increased.

The narrowing of territories that had come with the increasing proportion of root plants in the diet had made Thule cultures less mobile, and this reduction of territory size and decline of mobility, in a culture which was already naturally increasing its harvest, for a larger or more intensive harvest of these plants than would otherwise have taken place.

The result was that even before the Agricultural revolution, these plants were well established as a minor but significant part of the Thule diet. They were well known to the Thule, particularly their growing locations and habits, their properties, and something of their life cycles.

One factor which predisposed them to adoption was their perrenial nature. Like most Arctic plants they grew slowly, taking roughly three years to mature. What this meant however, is that as the root crops began to grow in organized cohorts - ie, one year patches, two year patches and three year harvest patches, the collateral harvesting of the secondary plants began to synch up. The result was that when the Thule harvesters went into a pasture region to collect Sweetvetch and other roots, they could reliably know that there were several other plants in the area that could be reliably harvested in profusion with very little extra effort. Essentially, the three year harvest cycle of the key root crops meant that other edible plants began to be synchronized for simultaneous harvesting.

None of these plants, by themselves, or in combination, could be deemed to grow reliably enough, in sufficient numbers, or be nutritionally productive enough to justify agriculture on their own. But, pardon the pun, knowledge and cultural traditions of them, and their association with the root plants, was deeply rooted enough in Thule culture, sufficiently ingrained, that the Agricultural Revolution would, inevitably pick them up as they exploded.

So, what were these plants, and where did they come from? Let’s have a look.

The Thule planting and harvest culture venerated threes. There were the ‘Three Gifts’ of Sweetveetch, Claytonia and Roseroot. There were the ‘Three Years’ harvest period, the ‘Three fields’ system of rotating harvest. Thule Shamans identified the ‘Three Good Seasons’ for harvest, and the ‘Three Good Directions’ for planting slopes - south, east, west.

Early in the Agricultural revolution, new cultivars were added to the ‘Three Gifts’ generally known as the ‘Three Lesser Gifts’ although technically there were five or six of them in all, when the collective contributions of the three originating agricultural complexes were added together.

These were in no way brand new plants. Rather, they had all been regularly, if sometimes intermittently harvested by the Thule culture These plants differed significantly from the Three Gifts in key ways.

Unlike the Three Gifts, these cultivars for the most part were not subject to pre-agricultural practices. They were harvested where they grew, but there was little effective effort to thank the spirits. The habit of replanting root cuttings was absent. There was no effort to propagate the plants to new habitats or fields, as with Sweetvetch and later Claytonia and Roseroot. There was no particular effort to encourage their growth, as with Roseroot or Claytonia by careful planting or adjustments to local conditions. They were simply picked where they were found at appropriate seasons, and any gifts made to the spirits were usually not ones that produced significant effects.

The new cultivars differed from the old ones in that mostly rather than producing edible roots, they generated edible leafs and stems. Nutritionally, they were much less essential, and had overall less nutrition, than the root plants, but still had some genuine significance. In the hunter/gatherer phase, they had minimal significance, and all else being equal would never have amounted to any substantial part of the Thule diet.

On the other hand, they shared some key features with the root crops. They were all flowering perrenials, which took two to four years. Most of them were pioneer species like Sweetvetch, hardy opportunists adept at taking root in and colonizing disturbed or stripped down environments. Most could and would reproduce vegetatively. And all of them were of the hardy arctic variety, adapted to poor soils, harsh conditions.

The harvest of the Root crops tended to encourage the harvesting of other edible plants in the area. Essentially, if the Thule were making the investment to remain in certain areas a little longer to dig up Sweetvetch and Claytonia, it made sense to use any spare time to catch or harvest whatever else the local area offered. So these plants tended to be harvested with increasing frequency and became more significant as the importance of the root plants increased.

The narrowing of territories that had come with the increasing proportion of root plants in the diet had made Thule cultures less mobile, and this reduction of territory size and decline of mobility, in a culture which was already naturally increasing its harvest, for a larger or more intensive harvest of these plants than would otherwise have taken place.

The result was that even before the Agricultural revolution, these plants were well established as a minor but significant part of the Thule diet. They were well known to the Thule, particularly their growing locations and habits, their properties, and something of their life cycles.

One factor which predisposed them to adoption was their perrenial nature. Like most Arctic plants they grew slowly, taking roughly three years to mature. What this meant however, is that as the root crops began to grow in organized cohorts - ie, one year patches, two year patches and three year harvest patches, the collateral harvesting of the secondary plants began to synch up. The result was that when the Thule harvesters went into a pasture region to collect Sweetvetch and other roots, they could reliably know that there were several other plants in the area that could be reliably harvested in profusion with very little extra effort. Essentially, the three year harvest cycle of the key root crops meant that other edible plants began to be synchronized for simultaneous harvesting.

None of these plants, by themselves, or in combination, could be deemed to grow reliably enough, in sufficient numbers, or be nutritionally productive enough to justify agriculture on their own. But, pardon the pun, knowledge and cultural traditions of them, and their association with the root plants, was deeply rooted enough in Thule culture, sufficiently ingrained, that the Agricultural Revolution would, inevitably pick them up as they exploded.

So, what were these plants, and where did they come from? Let’s have a look.

Almost One of the Big Three - First of the Secondary Domesticates

Alpine Bistort - Persicaria Vivipara. Very nearly one of the Three Gifts, and is by far the most credible candidate for the Thule’s ‘Fourth Domesticate.’ Bistort is universally acknowledged as a pivotal member of the 'Three Lesser Gifts' The identity of the other two lesser gifts, or the ranking of various secondary cultivars can be debated, but Bistort's place is assured.

Bistort is a short perrenial flowering plant, growing to about a foot in height, with a short thick rootstock or rhizome (a Rhizome is the thick underground stem of the plant, before it proliferates into thready roots. ‘Rhizome’ 'rootstock' and ‘root’ are sometimes used interchangeably) and willow like leaves, with a lifespan of three to four years. It produces small white or pink flowers. Below the flowers form small bulbs which are actually miniature plants, and which take root when detached. Sometimes these bulbs actually form leafs of their own before falling off the plant. The plant reproduces vegetatively through the bulbs or by fragmentation or seeding. It’s a very distinctive looking plant.

The rootstock or rhizome, is not very big, about the size of an unshelled peanut. But it is edible with a sweet nutty flavour, and can be eaten raw or roasted. In OTL it was harvested by Chukchi in Asia, who by all accounts were quite good at it, as well as by Inuit from Greenland and Alaska. The bulbs clinging under the flowers are also edible, tasting like almonds, giving the plant its name ‘Inuit Beads’ or ‘Inuit Nuts.’ In addition cooked leaves resembling spinach in flavour and appearance.

Bistort was common throughout the Thule range. It’s range actually exceeded Sweetvetch since it grew on the arctic Islands as far north as Ellesmere. Sweetvetch during the pre-agricultural period, didn’t get above the latitudes of Baffin Island.

Bistort leant itself even more readily to the replanting and planting practices that were evolving around Sweetvetch. Bistort was easier than Sweetvetch, all you had to do, rather than re-planting a root cutting, was to offer one or two of the bulbs that could be picked off the stem to the spirits of the earth. They would readily fall off themselves if conditions were right, and their occasional propensity to grow their own leaves while on the main plant made it clear that new plants would spring from them.

Bistort was a key intermediary in the development of Sweetvetch practices. The practice of picking and planting bulbs from Bistort was generalized over to collecting and planting seed pods from Sweetvetch.

Bistort, in most areas was harvested alongside Sweetvetch and benefitted from the same evolving cultural practices. It preceded either or both Claytonia and Roseroot as a regularly harvested root plant during the Thule expansion, and in the far north, it went beyond the range of Sweetvetch as literally the sole pseudo-cultivar.

So, why wasn’t Bistort one of the big three? Or big four? It had a couple of problems.

First, although it had more edible components than Sweetvetch or Claytonia, its key component, the edible root (rhizome) was comparatively tiny, about the size of an unshelled peanut, as I said. You had to harvest a lot of them to get any significant quantity, and that meant a lot more effort invested. The other root plants all offered a lot more return on the labour investment, which is why Roseroot and Claytonia expanded so readily.

The other big problem was that Bistort, in comparison to its rivals, was a more demanding plant. It preferred richer soils although it responded wonderfully to manure. Richer soils were at a premium in the Arctic, and its rivals tolerated poorer soils. It was also a plant that liked water rich soils. The Arctic was often dry, and its rivals were, as a whole less water hungry or more drought tolerant.

Bistort did have two things going for it. It tended to grow in profusion around human dwellings and camps, predator lairs, or long term bird nesting sites where organic garbage or manure would give it the critical boost. In these places, eminently predictable, it would grow in profusion in luxious beds. The proximity to humans, the clearly identifiable or predictable locations, and the growth density ensured that it could be regularly, reliably and profitably harvested, even if its growth requirements were so specific that it couldn’t be spread as widely as its rivals.

It’s clear responsiveness to manure however, helped to develop and incorporate the concept of fertilizer in Thule Agriculture, although the elements of that fertilizer were often sparse in the barren Arctic environment. Still, the Thule realized that it was possible to enrich soils, and that this could pay off quickly and directly, particularly with plants like Bistort.

In addition, its growth behaviour and lifestyle was essentially identical to the three root crops. This meant that there was essentially no intellectual leap to adopt Bistort. All that had to be done was to simply apply the existing techniques and habits, the cultural methods unchanged. Pretty much every other secondary cultivar required adaptation or innovation to incorporate into the package. Bistort, for want of a better word, was off the shelf and pre-fit.

Finally, Bistort was particularly widespread and cold tolerant. It was able to survive in the northernmost ranges, including Ellesmere Island, beyond the distribution of its rivals. While the extensive use of microclimates expanded the range of Root crops, Bistort profited heavily. In the Islands above Baffin, Bistort was often a strong candidate to anchor local agricultural or horticultural efforts. At the other extreme, Bistort thrived and became close to a staple in the McKenzie river basin, which contained the richest soils and most reliable waters in the Thule realm.

It therefore comes as no surprise that when the Agricultural revolution comes, Bistort is readily incorporated as a cultivar by all three agricultural founders, who treated it as an additional root crop, or that its cultivation spread and intensified.

The wide distribution of Bistort, and the simultaneous cultivation has given Bistort a diversity of genetic expression to rival Sweetvetch. Human selection began to modify Bistort earlier and faster than Sweetvetch. Essentially, in the case of Bistort, it was much easier a more intuitively natural gift to the spirits to drop a few extra bulbs where the root was comparatively large or where the plant sported more than the usual number of bulbs. This selected naturally for larger roots and more bulbs.

Even before the Agricultural revolution, a domestic version of Bistort was emerging in many areas with a larger root and large number of bulbs. Following the Agricultural revolution selection pressure became much more intense, and fully domesticated varieties emerged with as many as two dozen bulbs and roots the size of turnips or small potatoes.

Alpine Bistort - Persicaria Vivipara. Very nearly one of the Three Gifts, and is by far the most credible candidate for the Thule’s ‘Fourth Domesticate.’ Bistort is universally acknowledged as a pivotal member of the 'Three Lesser Gifts' The identity of the other two lesser gifts, or the ranking of various secondary cultivars can be debated, but Bistort's place is assured.

Bistort is a short perrenial flowering plant, growing to about a foot in height, with a short thick rootstock or rhizome (a Rhizome is the thick underground stem of the plant, before it proliferates into thready roots. ‘Rhizome’ 'rootstock' and ‘root’ are sometimes used interchangeably) and willow like leaves, with a lifespan of three to four years. It produces small white or pink flowers. Below the flowers form small bulbs which are actually miniature plants, and which take root when detached. Sometimes these bulbs actually form leafs of their own before falling off the plant. The plant reproduces vegetatively through the bulbs or by fragmentation or seeding. It’s a very distinctive looking plant.

The rootstock or rhizome, is not very big, about the size of an unshelled peanut. But it is edible with a sweet nutty flavour, and can be eaten raw or roasted. In OTL it was harvested by Chukchi in Asia, who by all accounts were quite good at it, as well as by Inuit from Greenland and Alaska. The bulbs clinging under the flowers are also edible, tasting like almonds, giving the plant its name ‘Inuit Beads’ or ‘Inuit Nuts.’ In addition cooked leaves resembling spinach in flavour and appearance.

Bistort was common throughout the Thule range. It’s range actually exceeded Sweetvetch since it grew on the arctic Islands as far north as Ellesmere. Sweetvetch during the pre-agricultural period, didn’t get above the latitudes of Baffin Island.

Bistort leant itself even more readily to the replanting and planting practices that were evolving around Sweetvetch. Bistort was easier than Sweetvetch, all you had to do, rather than re-planting a root cutting, was to offer one or two of the bulbs that could be picked off the stem to the spirits of the earth. They would readily fall off themselves if conditions were right, and their occasional propensity to grow their own leaves while on the main plant made it clear that new plants would spring from them.

Bistort was a key intermediary in the development of Sweetvetch practices. The practice of picking and planting bulbs from Bistort was generalized over to collecting and planting seed pods from Sweetvetch.

Bistort, in most areas was harvested alongside Sweetvetch and benefitted from the same evolving cultural practices. It preceded either or both Claytonia and Roseroot as a regularly harvested root plant during the Thule expansion, and in the far north, it went beyond the range of Sweetvetch as literally the sole pseudo-cultivar.

So, why wasn’t Bistort one of the big three? Or big four? It had a couple of problems.

First, although it had more edible components than Sweetvetch or Claytonia, its key component, the edible root (rhizome) was comparatively tiny, about the size of an unshelled peanut, as I said. You had to harvest a lot of them to get any significant quantity, and that meant a lot more effort invested. The other root plants all offered a lot more return on the labour investment, which is why Roseroot and Claytonia expanded so readily.