You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

TL-191: Filling the Gaps

- Thread starter Craigo

- Start date

Wolfpaw

Banned

LIST OF PRESIDENTS OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES OF AMERICA (1861-1944)

- Jefferson Davis, 1861-1868 (Democrat)

- Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter, 1868-1874 (Democrat)

- Zebulon Baird Vance, 1874-1880 (Democrat)

- James Longstreet, 1880-1886 (Democrat)

- John Tyler Morgan, 1886-1892 (Whig)

- Fitzhugh Lee, 1892-1898 (Whig)

- Matthew Butler, 1898-1904 (Whig)

- Robert Love Taylor, 1904-1910 (Whig)

- Woodrow Wilson, 1910-1916 (Whig)

- Gabriel Semmes, 1916-1922 (Whig)

- Wade Hampton V, 1922 (Whig)*

- Burton Mitchel, 1922-1934 (Whig)

- Jake Featherston, 1934-1944 (Freedom)*

- Donald Partridge, 1944 (Freedom)

LIST OF PRESIDENTS OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES OF AMERICA (1861-1944)

*Assassinated

- Jefferson Davis, 1861-1868 (Democrat)

- Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter, 1868-1874 (Democrat)

- Zebulon Baird Vance, 1874-1880 (Democrat)

- James Longstreet, 1880-1886 (Democrat)

- John Tyler Morgan, 1886-1892 (Whig)

- Fitzhugh Lee, 1892-1898 (Whig)

- Matthew Butler, 1898-1904 (Whig)

- Robert Love Taylor, 1904-1910 (Whig)

- Woodrow Wilson, 1910-1916 (Whig)

- Gabriel Semmes, 1916-1922 (Whig)

- Wade Hampton V, 1922 (Whig)*

- Burton Mitchel, 1922-1934 (Whig)

- Jake Featherston, 1934-1944 (Freedom)*

- Donald Partridge, 1944 (Freedom)

This is a bit different from your last list.

I considered having Fitzhugh Lee in the same position, but the information we're given generally indicates that the 1890s were not all that successful foreign policy wise, due to Haiti and Nicaragua. I thought that it would be against the spirit of 191, where apparently the Lees can do no wrong, for one of their number to be in office then.

Wolfpaw

Banned

Sorry about that. Do you think it's better or worse, because I'd be more than happy to change it.This is a bit different from your last list.

Those're good points. What if we had it this way:I considered having Fitzhugh Lee in the same position, but the information we're given generally indicates that the 1890s were not all that successful foreign policy wise, due to Haiti and Nicaragua. I thought that it would be against the spirit of 191, where apparently the Lees can do no wrong, for one of their number to be in office then.

- James Longstreet, 1880-1886

- Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar II, 1886-1892

- John Tyler Morgan, 1892-1898

- Fitzhugh Lee, 1898-1904

Morgan was a bellicose, bumbling, expansionist hawk, so if the '90s are a bad decade for Confederate FP (as you correctly pointed out), then he'd probably be the reason why.

And Lee dies about a month after he'd leave office ITTL, so we needn't worry about that.

Sorry about that. Do you think it's better or worse, because I'd be more than happy to change it.

Those're good points. What if we had it this way:

I figure that Longstreet would try to get Lamar to succeed him as he would likely follow Longstreet's manumission agenda, something that a South Carolinian like Butler probably wouldn't.

- James Longstreet, 1880-1886

- Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar II, 1886-1892

- John Tyler Morgan, 1892-1898

- Fitzhugh Lee, 1898-1904

Morgan was a bellicose, bumbling, expansionist hawk, so if the '90s are a bad decade for Confederate FP (as you correctly pointed out), then he'd probably be the reason why.

And Lee dies about a month after he'd leave office ITTL, so we needn't worry about that.

Good catch, I was wondering about that.

Would Lamar be well disposed towards manumission? He was a Mississippian, no? That's one of the reasons I included Jackson, as HFR paints him as more or less converted by Longstreet.

Morgan's a good choice. I wanted to include at least ONE Confederate who died in the real war as a President, which is why I chose Gist.

You went with Champ Clark and Robert Taylor at various times - I think they're both good choices for the pre-Wilson President (I think I originally had them one after another, actually.) We know by GW: AF that the industrialists (think the Sloss brothers) have joined the landed aristocracy as the barons of the Whig party, so Taylor and Clark would illustrate the increasing importance of commerce in the 20th century Confederacy.

Last edited:

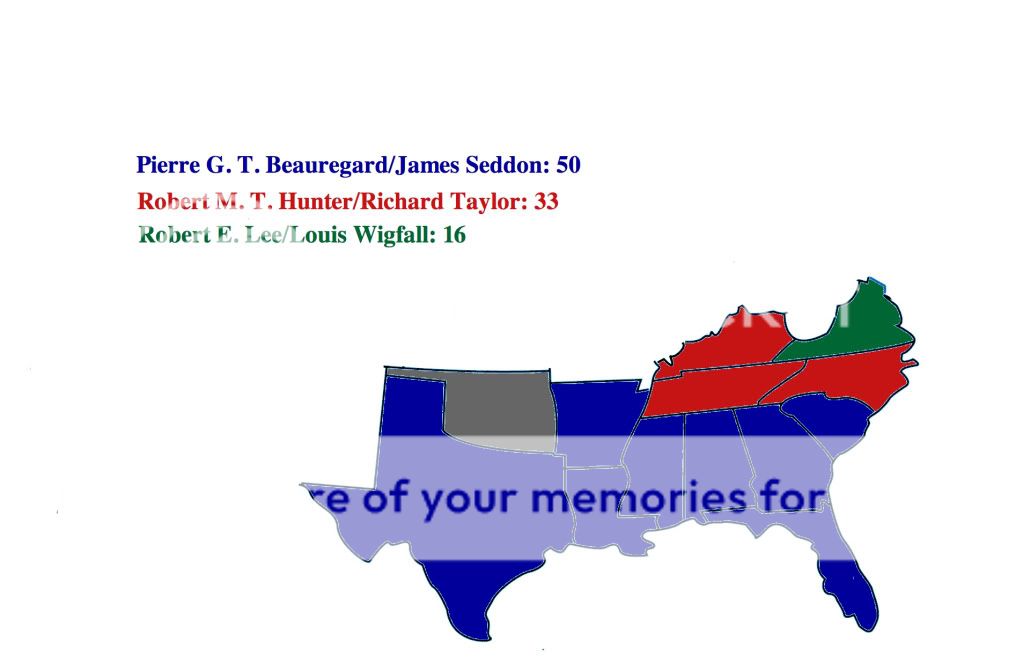

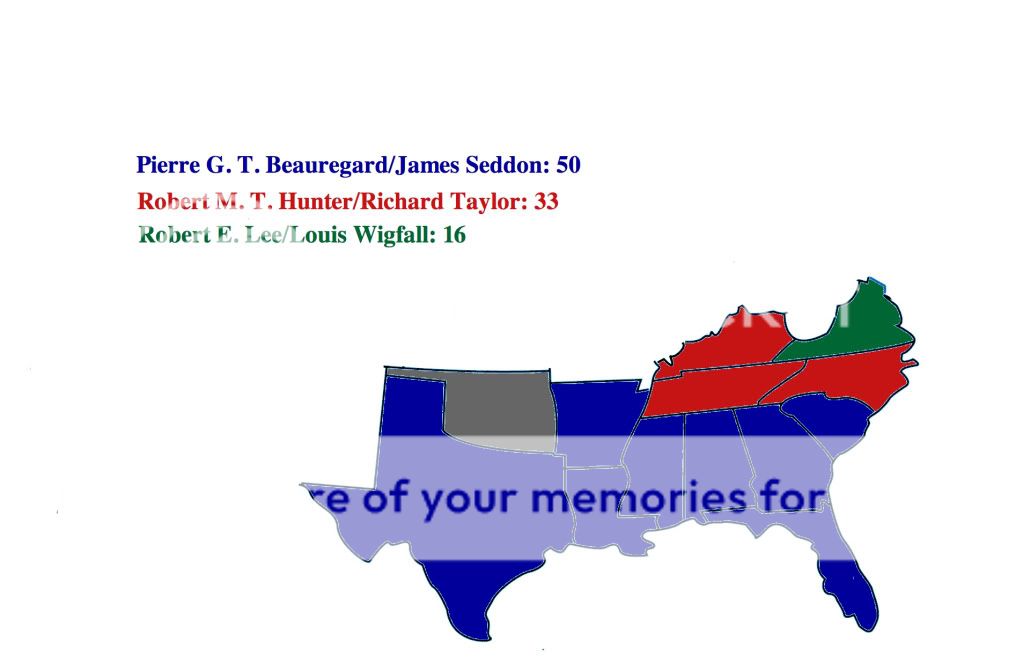

Confederate presidential election, 1867

This contest is highly unusual in North American annals: An election which was dominated by a man who was not a candidate and did not win. Robert E. Lee had achieved towering fame in and outside his native South for his brilliant, war-winning Pennsylvania campaign five years before, and from 1863 onwards had ably served as General-in-Chief of the Confederate Army (a post that the Congress created specifically for him). But he was getting on in years, and was greatly troubled by heart pains that often prevented him from riding working at his desk.

In response to a flood of encouragement to run, e finally responded in the spring of 1867, in the form of a letter to the editor of the Richmond Examiner, in which he thanked his many supporters, but declined to run for the Presidency, citing his current responsibilities and the fact that he had already achieved his heart's desire, freedom for Virginia.

He was nonetheless, placed on the ballot by supporters in several states, including Virginia. And the hounding would not stop, as he was pressed to endorse one of the two contenders: General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, who had fired on Fort Sumter and won the Battle of Manassas; and Senator Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter, a former Secretary of State who had successfully negotiated a treaty of friendship with President Horatio Seymour up north.

(The grandificent names of these two men is another one of history's oddities.)

Lee steadfastly refused to comment publicly on the race, which became a contest of personalities and resumes over policies, as the two men had few real disagreements over what they would do as President. (RMT Hunter favored an early defensive alliance with Britain and France, which would not be forthcoming for nearly two decades.) The division between the "military" and "political" classes were clearly illustrated by their choices in running mates: Beauregard reached out to Secretary of War James Seddon, in what was seen in some quarters as a naked appeal for Virginian votes; while Hunter chose General Richard Taylor of Louisiana, the son of Zachary Taylor. In the six states in which he was on the ballot, Lee was paired with a variety of running mates, including Louis Wigfall of Texas in Virginia.

In the end, it came down to the upper South and the east vs. the lower South and the west. Many in the Confederacy seemed to have feared political domination by Virginia, reminiscent of the early days of the United States, and rallied around the "outsider," who happened to have an appealing war record.

P.G.T. Beauregard: 50 electoral votes, 41% of the vote

R.M.T. Hunter: 33 electoral votes, 36% of the vote

Robert E. Lee: 16 electoral votes, 23% of the vote

Lee dominated the voting in Virginia - in the five states where all three were on the ballot, this was the only contest where one candidate won a majority of the popular vote. Hunter took Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina, and Beauregard the rest. Even if Hunter had won his home state of Virginia, Beauregard would have had a majority in the electoral college.

South Carolina, alone of the states, chose its electors by vote of the legislature, which supported the hero of Fort Sumter. Had they voted for Hunter, no candidate would have a majority in the electoral college, and the election would have been decided in the House. Hunter, a longtime legislator who was well-respected in that body, would likely have become the second Confederate President in that scenario.

This contest is highly unusual in North American annals: An election which was dominated by a man who was not a candidate and did not win. Robert E. Lee had achieved towering fame in and outside his native South for his brilliant, war-winning Pennsylvania campaign five years before, and from 1863 onwards had ably served as General-in-Chief of the Confederate Army (a post that the Congress created specifically for him). But he was getting on in years, and was greatly troubled by heart pains that often prevented him from riding working at his desk.

In response to a flood of encouragement to run, e finally responded in the spring of 1867, in the form of a letter to the editor of the Richmond Examiner, in which he thanked his many supporters, but declined to run for the Presidency, citing his current responsibilities and the fact that he had already achieved his heart's desire, freedom for Virginia.

He was nonetheless, placed on the ballot by supporters in several states, including Virginia. And the hounding would not stop, as he was pressed to endorse one of the two contenders: General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, who had fired on Fort Sumter and won the Battle of Manassas; and Senator Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter, a former Secretary of State who had successfully negotiated a treaty of friendship with President Horatio Seymour up north.

(The grandificent names of these two men is another one of history's oddities.)

Lee steadfastly refused to comment publicly on the race, which became a contest of personalities and resumes over policies, as the two men had few real disagreements over what they would do as President. (RMT Hunter favored an early defensive alliance with Britain and France, which would not be forthcoming for nearly two decades.) The division between the "military" and "political" classes were clearly illustrated by their choices in running mates: Beauregard reached out to Secretary of War James Seddon, in what was seen in some quarters as a naked appeal for Virginian votes; while Hunter chose General Richard Taylor of Louisiana, the son of Zachary Taylor. In the six states in which he was on the ballot, Lee was paired with a variety of running mates, including Louis Wigfall of Texas in Virginia.

In the end, it came down to the upper South and the east vs. the lower South and the west. Many in the Confederacy seemed to have feared political domination by Virginia, reminiscent of the early days of the United States, and rallied around the "outsider," who happened to have an appealing war record.

P.G.T. Beauregard: 50 electoral votes, 41% of the vote

R.M.T. Hunter: 33 electoral votes, 36% of the vote

Robert E. Lee: 16 electoral votes, 23% of the vote

Lee dominated the voting in Virginia - in the five states where all three were on the ballot, this was the only contest where one candidate won a majority of the popular vote. Hunter took Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina, and Beauregard the rest. Even if Hunter had won his home state of Virginia, Beauregard would have had a majority in the electoral college.

South Carolina, alone of the states, chose its electors by vote of the legislature, which supported the hero of Fort Sumter. Had they voted for Hunter, no candidate would have a majority in the electoral college, and the election would have been decided in the House. Hunter, a longtime legislator who was well-respected in that body, would likely have become the second Confederate President in that scenario.

Last edited:

Craigo, I must say that you never cease to impress me

Thanks, and I really appreciate the good contributions and suggestions that readers are giving. I wish I could afford to work on this stuff a lot more.

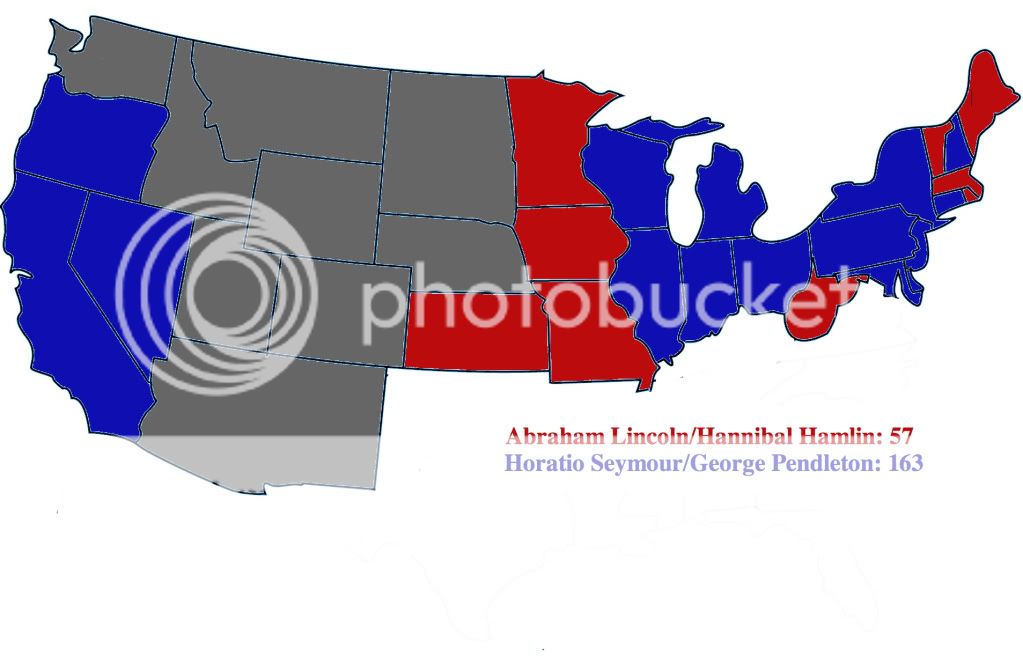

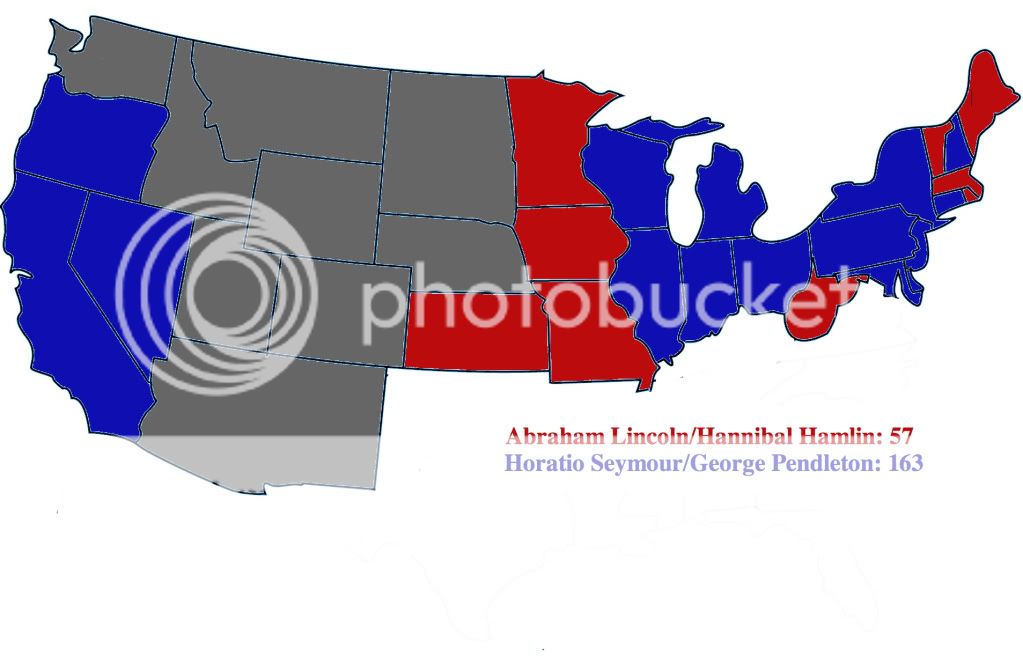

United States presidential election, 1864

Abraham Lincoln was a dead man walking. Though he would live another twenty years, dying naturally on Good Friday in 1885, he was a spent political force in 1864. The fact that he even retained the Republican nomination merits attention.

The best friend a man can have is a poor enemy, and unlike in the War of Secession, Lincoln had those aplenty in the Republican Party. Chief among them was Salmon Chase, a man of great integrity and even greater ambition who served as Lincoln's Secretary of Treasury. Chase had used his position and his abolitionism to build a network of political patrons and supporters. Lincoln was well aware of these shenanigans, but chose to overlook them.

There was some wisdom in this, as the political winds were blowing against abolitionism, and allowing a radical splinter group to fulminate against him helped Lincoln secure his right flank. He also cannily predicted that this splinter group would splinter again, as John C. Fremont, the 1856 GOP nominee, clearly wished to try again. Lincoln had publicly overruled Fremont when the latter, as a general, had attempted to free Confederate slaves on his own hook, becoming a radical hero in failure.

These radicals met at at their own convention in May 1864 - they hoped that by threatening a third-party candidacy, Lincoln could be persuaded to step aside and allow the abolitionist to control the party. But Lincoln's allies, most notably the Blair family, succeeded in manipulating the radicals into ensuring that both ambitious contenders, Chase and Fremont, were put into nomination, along with Lincoln. With the convention deadlocked the Blairs, who controlled the Missouri and Maryland delegations, staged a walkout of the Fremont faction, leaving the Radicals to nominate a weakened Chase, who would later withdraw when it became clear that his backers had abandoned him.

Fremont, who only now realized how badly he had been used, attempted to make a comeback at the GOP convention the next month, but his legs had been cut out from under him. Moderates dominated the ranks of the delegates, and Lincoln was easily re-nominated, along with his 1860 running mate, Hannibal Hamlin of Maine. Lincoln was not especially fond of Hamlin, and only kept him on the ticket after Pennsylbania Jeremiah Black, a staunch unionist in Buchanan's cabinet, declined the offer. In the end, the rumblings of discontent among the abolitionists over te Chase-Fremont affair compelled Lincoln to retain Hamlin. (Had Lincoln his choice, he would have nominated Black or Montgomery Blair of Maryland, his former Postmaster General and current Attorney General, but the Blairs had become antathema t much of the party after the Radical Republican fiasco.)

There was little such drama on the other side, where Governor Horatio Seymour of New York marched to an easy triumph at the Democratic National Convention, winning a two-thirds majority on the second ballot. His only real opposition came from another Seymour, Thomas from Connecticut, who attracted scattered New England votes, and Speaker of the House Daniel Voorhees of Indiana, the candidate of the western Democracy. (Voorhees declined the offer of the Vice-Presidency; it was then extended to Rep. George Pendleton of Ohio, who accepted.) Seymour favored concluding the treaty with the Confederates and putting the matter to rest; he was put somewhat on the defensive when Lincoln successfully concluded a treaty that retained Missouri, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia and the New Mexico Territory, ceding only Kentucky and the Indian Territory. (Confederate historians have long alleged that British mediator, the diplomat Lord Lyons, had shown undue favor the United States. It is known that Lyons was frequently in poor health, and would depart North America permanently shortly after the signing. )

Lincoln's last ditch appeal to the patriotism of the North may have slowed the bleeding, but nothing could have stopped it. The Republican party had lost its majority in the House in 1862, and now the Senate followed. Lincoln was defeated by a huge margin (though ironically, he won almost exactly as many votes as he had four years previously).

Abraham Lincoln/Hannibal Hamlin: 52 electoral votes, 44% of the vote

Horatio Seymour/George Pendleton: 170 electoral votes, 54% of the vote

Lincoln's efforts to stand up for the border states paid off to some extent, as he won West Virginia and Missouri, and in general did better than in the belt of counties bordering the South than he had in 1860. He also performed well in the upper North, winning most of New England's votes as well as the Plains states. But heavy defections in the lower North doomed the campaign; the Democratic ticket went into the election with a stranglehold on New York and Ohio, which made Lincoln's path to re-election exceedingly narrow. When the early returns from Pennsylvania had the Republican ticket running behind 1860, the President knew it was over. His last act as President would be to spend his lame-duck winter persuading Congress to pass the proposed Thirteenth Amendment banning slavery and send it to the states for ratification. He succeeded, but like his own career, the Thirteen Amendment would not be concluded for nearly two decades.

Abraham Lincoln was a dead man walking. Though he would live another twenty years, dying naturally on Good Friday in 1885, he was a spent political force in 1864. The fact that he even retained the Republican nomination merits attention.

The best friend a man can have is a poor enemy, and unlike in the War of Secession, Lincoln had those aplenty in the Republican Party. Chief among them was Salmon Chase, a man of great integrity and even greater ambition who served as Lincoln's Secretary of Treasury. Chase had used his position and his abolitionism to build a network of political patrons and supporters. Lincoln was well aware of these shenanigans, but chose to overlook them.

There was some wisdom in this, as the political winds were blowing against abolitionism, and allowing a radical splinter group to fulminate against him helped Lincoln secure his right flank. He also cannily predicted that this splinter group would splinter again, as John C. Fremont, the 1856 GOP nominee, clearly wished to try again. Lincoln had publicly overruled Fremont when the latter, as a general, had attempted to free Confederate slaves on his own hook, becoming a radical hero in failure.

These radicals met at at their own convention in May 1864 - they hoped that by threatening a third-party candidacy, Lincoln could be persuaded to step aside and allow the abolitionist to control the party. But Lincoln's allies, most notably the Blair family, succeeded in manipulating the radicals into ensuring that both ambitious contenders, Chase and Fremont, were put into nomination, along with Lincoln. With the convention deadlocked the Blairs, who controlled the Missouri and Maryland delegations, staged a walkout of the Fremont faction, leaving the Radicals to nominate a weakened Chase, who would later withdraw when it became clear that his backers had abandoned him.

Fremont, who only now realized how badly he had been used, attempted to make a comeback at the GOP convention the next month, but his legs had been cut out from under him. Moderates dominated the ranks of the delegates, and Lincoln was easily re-nominated, along with his 1860 running mate, Hannibal Hamlin of Maine. Lincoln was not especially fond of Hamlin, and only kept him on the ticket after Pennsylbania Jeremiah Black, a staunch unionist in Buchanan's cabinet, declined the offer. In the end, the rumblings of discontent among the abolitionists over te Chase-Fremont affair compelled Lincoln to retain Hamlin. (Had Lincoln his choice, he would have nominated Black or Montgomery Blair of Maryland, his former Postmaster General and current Attorney General, but the Blairs had become antathema t much of the party after the Radical Republican fiasco.)

There was little such drama on the other side, where Governor Horatio Seymour of New York marched to an easy triumph at the Democratic National Convention, winning a two-thirds majority on the second ballot. His only real opposition came from another Seymour, Thomas from Connecticut, who attracted scattered New England votes, and Speaker of the House Daniel Voorhees of Indiana, the candidate of the western Democracy. (Voorhees declined the offer of the Vice-Presidency; it was then extended to Rep. George Pendleton of Ohio, who accepted.) Seymour favored concluding the treaty with the Confederates and putting the matter to rest; he was put somewhat on the defensive when Lincoln successfully concluded a treaty that retained Missouri, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia and the New Mexico Territory, ceding only Kentucky and the Indian Territory. (Confederate historians have long alleged that British mediator, the diplomat Lord Lyons, had shown undue favor the United States. It is known that Lyons was frequently in poor health, and would depart North America permanently shortly after the signing. )

Lincoln's last ditch appeal to the patriotism of the North may have slowed the bleeding, but nothing could have stopped it. The Republican party had lost its majority in the House in 1862, and now the Senate followed. Lincoln was defeated by a huge margin (though ironically, he won almost exactly as many votes as he had four years previously).

Abraham Lincoln/Hannibal Hamlin: 52 electoral votes, 44% of the vote

Horatio Seymour/George Pendleton: 170 electoral votes, 54% of the vote

Lincoln's efforts to stand up for the border states paid off to some extent, as he won West Virginia and Missouri, and in general did better than in the belt of counties bordering the South than he had in 1860. He also performed well in the upper North, winning most of New England's votes as well as the Plains states. But heavy defections in the lower North doomed the campaign; the Democratic ticket went into the election with a stranglehold on New York and Ohio, which made Lincoln's path to re-election exceedingly narrow. When the early returns from Pennsylvania had the Republican ticket running behind 1860, the President knew it was over. His last act as President would be to spend his lame-duck winter persuading Congress to pass the proposed Thirteenth Amendment banning slavery and send it to the states for ratification. He succeeded, but like his own career, the Thirteen Amendment would not be concluded for nearly two decades.

Last edited:

bguy

Donor

Lincoln was easily re-nominated, along with his cunning ally Montgomery Blair of Maryland, Lincoln's former Postmaster General and current Attorney General.

One minor quibble about an otherwise excellent entry, there's a passage in How Few Remain that says Hannibal Hamlin stayed on the ticket in the 1864 election.

One minor quibble about an otherwise excellent entry, there's a passage in How Few Remain that says Hannibal Hamlin stayed on the ticket in the 1864 election.

Oops. I'll fix it.

Oops. I'll fix it.

Another Comment I seem to remember in How Few Remain that Longstreet was already a Whig. I would imagine that the southern dems would have started calling themselves Whigs in honor of the English Party that helped free America in 1789. I say that because in another novel I remember Pinkard making a comment about how Southerners where "real" Americans so I think they would make that homage to the Whigs and British support. Otherwise, I am not sure, as to how they became called Whigs in the first place; the American Whig party was not a southern party IOTL.

I find Turtledove's political parties difficult to understand. I wish he explained it better, but that is not really the point of the 191 series.

Another Comment I seem to remember in How Few Remain that Longstreet was already a Whig. I would imagine that the southern dems would have started calling themselves Whigs in honor of the English Party that helped free America in 1789. I say that because in another novel I remember Pinkard making a comment about how Southerners where "real" Americans so I think they would make that homage to the Whigs and British support. Otherwise, I am not sure, as to how they became called Whigs in the first place; the American Whig party was not a southern party IOTL.

I find Turtledove's political parties difficult to understand. I wish he explained it better, but that is not really the point of the 191 series.

Plus Featherston said that Jefferson Davis, "Lee" and Longstreet were all great Whigs.

I can't imagine Massachusetts and Rhode Island voting for Lincoln. With the south now an independent country, the U.S. government would be completely broke for atleast a decade since nearly all of the government was funded by tariffs from southern ports. The "Panic of 1863" as it was called in How Few Remain, would have lasted for quite some time. Samuel Clemens described the finances as 4 cents for every gold dollar, and for about 2 or 3 weeks as 3 cents per gold dollar. The New England manufacturers would have been hurt the most by this, and probably would have blamed Lincoln and the Republicans. Great job on the maps though.

Plus Featherston said that Jefferson Davis, "Lee" and Longstreet were all great Whigs.

I leafed through HFR and couldn't find any references to Longstreet being called a Whig at the time, but I'd appreciate it if anyone else could find the page.

There were in fact southern Whigs (Alexander Stephens, for one). The Impending Crisis by David Potter is a great resource for American politics just between the Mexican-American War and the Civil War.

Why they're called the Whigs - the Revolutionary connection is a good point. It's also worth noting that the Confederates would likely be loth to take any name associated with a current Yankee party, and historically the only major American parties have been called Federalists, Republicans, Democrats, or Whigs. "Federalist" is a nonstarter, obviously. And although American parties just before the Civil War were generally heterogeneous, there was a definite undercurrent of "privilege" in the Whigs, while the Democrats were nominally "populist." A party dominated by planters, like the early Whigs, might hew to that name, despite the fact that most of them were Democrats prewar.

I'm currently working on the development on Confederate political parties, some of which has been mentioned obliquely.

I can't imagine Massachusetts and Rhode Island voting for Lincoln. With the south now an independent country, the U.S. government would be completely broke for atleast a decade since nearly all of the government was funded by tariffs from southern ports. The "Panic of 1863" as it was called in How Few Remain, would have lasted for quite some time. Samuel Clemens described the finances as 4 cents for every gold dollar, and for about 2 or 3 weeks as 3 cents per gold dollar. The New England manufacturers would have been hurt the most by this, and probably would have blamed Lincoln and the Republicans. Great job on the maps though.

My (unscientific) method was to take the real 1864 results, and allocate to the GOP any state where Lincoln won by more than his national average of about 55%. There were a few exceptions - I gave Wisconsin to the Democrats, albeit narrowly, along with Ohio (Pendleton's influence on the ticket). I gave them the West too. The next version of the map will add Maine to the GOP column, due to Hamlin still being on the GOP ticket, and the fact that Lincoln garnered 60% there IOTL.

Lincoln won Massachusetts and Vermont with over two-thirds of the vote, so I couldn't justify flipping them.

(I still think keeping Hamlin is a boring and illogical choice, but this is HT's story, not mine.)

Last edited:

Sound logic. But I think the economy would definately swing Massachusetts to the Democrats (but I agree Vermont would remain solid Republican). Good thinking giving the West Coast to the Democrats.

Wolfpaw

Banned

I could see Maine remaining a Republican stronghold ITTL, seeing as how it had both vice presidential and presidential spots on the Republican ticket in that period..Oops. I'll fix it.

Then again, half of Maine was annexed to Canada after the Second Mexican War, so it would seem likely that the state would vote Democrat so they could atleast attempt to get it back if there was another war (Great War).

Share: