You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Lands of Red and Gold

- Thread starter Jared

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Threadmarks

View all 78 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Lands of Red and Gold #8: Of Birds, Bats and Bugs Lands of Red and Gold #7: True Wealth Lands of Red and Gold #6: Collapse and Rebirth Lands of Red and Gold #5: Life As It Once Was Lands of Red and Gold #4: What Lies Beneath The Earth Lands of Red and Gold #3: Yams of Red, Trees of Gold Lands of Red and Gold #2: What Grows From The Earth Lands of Red and Gold #1: Old Land, New TimesNice...

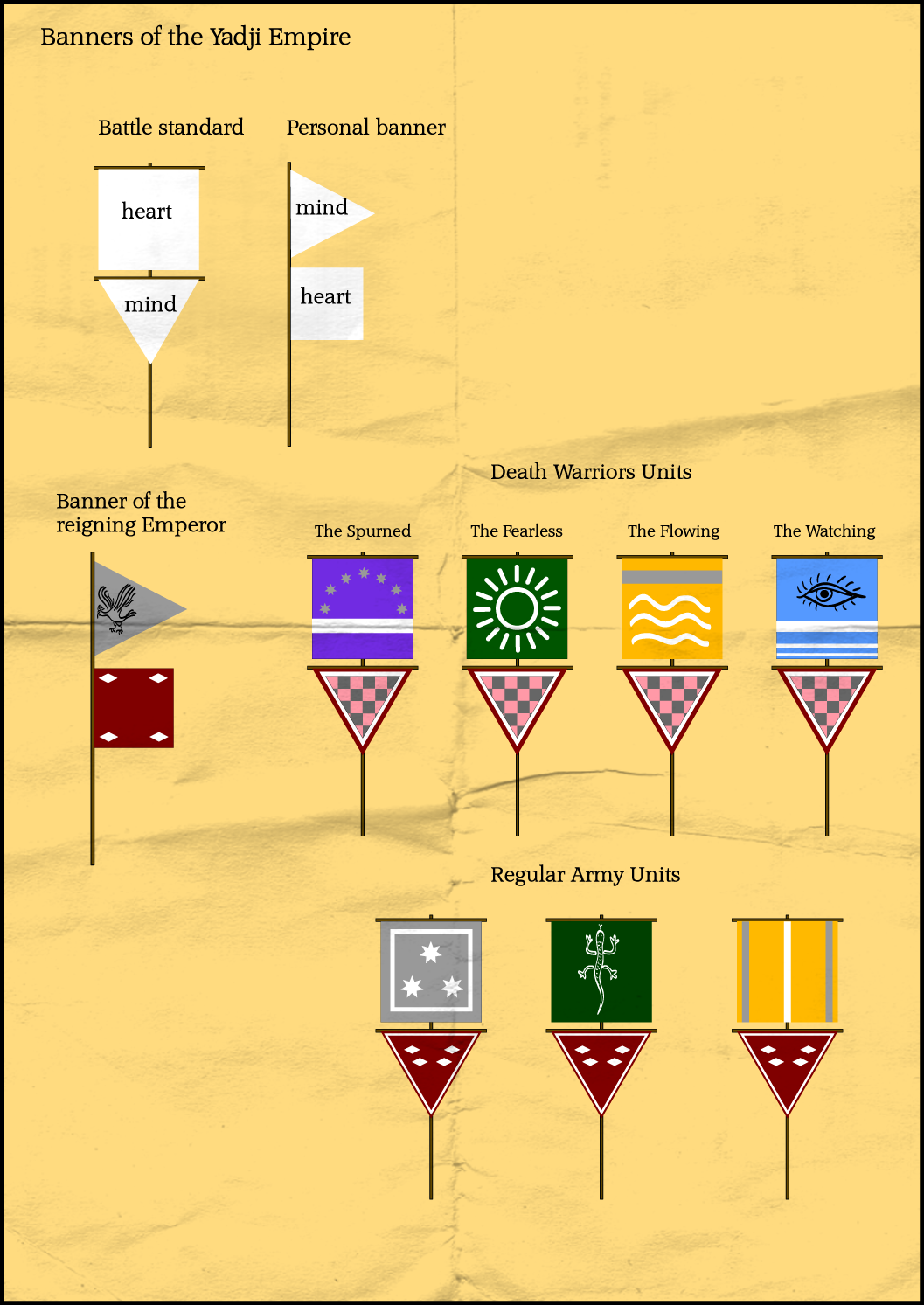

Edit: Just want to mention I love the pink/gray "Mind" of the Death Warriors. Very fitting.

Leave it to Jared to make pink the color of death and terror!

Edit: Just want to mention I love the pink/gray "Mind" of the Death Warriors. Very fitting.

Leave it to Jared to make pink the color of death and terror!

Last edited:

As always, Sapiento = awsome!

Nice...

Edit: Just want to mention I love the pink/gray "Mind" of the Death Warriors. Very fitting.

Leave it to Jared to make pink the color of death and terror!

Excellent banners there. Is there a reason the regular army units standards are not named?

Thank you all!

I made the banners after a description Jared gave me. He only mentioned one Death Warrrior unit, the Spurned, so I came up with names for the others.

For the regular units: you have to ask Jared if they have names. I could see a designation that use the town of the garrison and numbers, like 'the 3rd Birmingham' or 'the 1st Liverpool' for example.

Lands of Red and Gold #17: The Good Man

Lands of Red and Gold #17: The Good Man

In Australia, the driest of inhabited continents, water means life. Droughts are common, and even when rain does fall, it often does so in such abundance that floods are the end result. The irregularity of this rain is most pronounced in the interior, and naturally enough most of the inhabitants of the continent live nearer the coast. The outback – the red heart of the continent – is nearly devoid of water, and nearly devoid of human life.

In eastern Australia, the frontier between the outback and the settled districts is traditionally the River Darling. Rising in the mountain ranges of southern Queensland, the Darling drains a large part of the continent before emptying into the River Murray. The Darling is an extremely irregular river, often drying up completely, and at other times flooding so prodigiously that the waters can take six months to recede. Nonetheless, it became an important transport route during the early days of European settlement of Australia.

Beyond the Darling lies the red heart, the outback. The nearest part of this is called the Channel Country, a series of ancient flood plains marked by the courses of many dried up rivers. Rain seldom falls here, but when it does, it floods along these channels and drains into Lake Eyre, the largest lake in Australia, and which has no outlet to the sea. Most of the time, Lake Eyre is a flat, dry salt plain, but sometimes the rains from distant cyclones or monsoons fill the lake. When it does, fish spawn in great abundance, and waterbirds gather from across the vast interior to feed and breed by the shores. The lake dries out soon enough, the fish dying, the waterbirds moving on, and its bed reverts to a salt plain.

In the cyclically dry country beyond the Darling, Europeans found relatively little to interest them. Some rich mineral lodes have been mined, and sheep and cattle graze in stations (farms) which need very large areas to support their herds on the sparse vegetation, but otherwise the country is mostly empty.

In allohistorical Australia, the same river is called the Anedeli. To the Gunnagalic peoples who developed agriculture along the Nyalananga [River Murray], the Anedeli was for a very long time considered a frontier. The lower reaches of the Anedeli drained through country where the rainfall was extremely limited and agriculture almost impossible. In time, migrants used the Anedeli as a transportation route, following its course to the upper reaches. Here, they found more fertile country and a variety of mineral wealth – especially tin – which meant that the Anedeli became a much more important transportation route.

As Gunnagalic civilization developed over the centuries, they came to regard the Anedeli as one of the Five Rivers that watered the known world [1]. An empire arose, Watjubaga, which took its name from the Five Rivers which flowed through the heart of its territory. Four of those rivers had long-established cities and verdant agriculture and aquaculture along their banks. The fifth river, the Anedeli, continued to be used primarily as a transportation route, and it marked a frontier rather than a source of life.

To the Gunnagalic peoples, the country beyond the Anedeli was called the Red Lands, or the Hot Lands, or the Dry Country. They did have a few uses for it. Silver Hill [Broken Hill] gave them a rich source of silver, lead and zinc, and other mines gave them some valuable metals and minerals, especially varieties of ochre which they used for dyes. They sometimes mined salt and gypsum from the dry lake beds, and collected a few flavourings and fibres from some of the outback plants. For the most part, though, the Red Lands were a thinly-settled frontier fading into desert which was occupied only by sometimes hostile hunter-gatherer peoples.

Usually.

For the Red Lands had a brief flowering of more reliable agriculture, a time when the Anedeli became not a frontier but a treasured source of water for peoples who lived along its banks. Thanks to a rare shift in the climate, the rainfall along the lower Anedeli became sufficient enough to support several substantial cities and a separate kingdom. This time of flowering would come to an end, with the yams and wattles withering for lack of water and the cities abandoned to the desert. In that brief time, though, the kingdom beside the Anedeli witnessed the birth of the first evangelical religion on the continent; a new faith which would in time spread far beyond its shores...

* * *

At the turn of the tenth century AD, during the decline of the Watjubaga Empire, imperial authority was dying outside of the heartland of the Five Rivers. The Bungudjimay in the northeast had defeated imperial armies and were starting to raid the fringes of the tin and sapphire-producing regions of the north. In the east, the Patjimunra had just declared their independence from imperial authority. The Junditmara in the south were rising in perpetual rebellion, and the imperial governors were powerless to stop them.

In the midst of this chaos, it took some time for the imperial administration at Garrkimang [Narrandera] to notice a remarkable shift in the climate. The lands around the Anedeli had always been dry and barely worth farming. Yet over the last few decades, the usual winter rains had been heavier than usual, and reached further and further north. Summers and winters both had grown somewhat cooler, but not intolerably so. Any minor inconvenience that the colder temperatures caused was more than offset by the prospect of bountiful rains falling year after year [2].

Just after the turn of the century, news reached Garrkimang of another remarkable change. They knew, of course, of the distant salt bed that they called Papukurdna [Lake Eyre], and of the cycle of refilling and evaporation. Most of their salt came from smaller dry lakes, but they had sufficient contact with the hunter-gatherer peoples of the interior to hear about this greatest of dry lakes. Tales from these peoples, and confirmed by ‘civilized’ visitors, confirmed the extraordinary tale that this great lake had filled permanently, or so it seemed.

The years turned, with rebellions and defeats plaguing Watjubaga, yet still visitors reported that the former dry lake remained full. The heavier winter rains continued over the frontier of the River Anedeli and the Red Lands it bordered. In time, the existence of these heavier rains came to be seen as the natural state of affairs. In 912, then-First Speaker [Emperor] Lopitja announced the founding of a new city along the Anedeli, modestly named after himself. Farmers started to settle the lands around this new city of Lopitja [Wilcannia, New South Wales]. In time, most people forgot that this country had for so long been arid and too hostile to support agriculture [3].

The decades passed, and the Red Lands along the Anedeli became almost as well-populated as any other part of the Five Rivers. Yams and wattles flourished with the rains, and the expansion into this region gave them access to crops which had not been domesticated further south; bush pears and bush raisins as fruits and flavourings, and trees such as blue-leaved mallee as a spice [4]. They were not able to build artificial wetlands in quite the same way as on the other main rivers, but they did build some artificial lakes which could store Anedeli floodwaters and allow both fishing and irrigation.

Lopitja became a flourishing city, the largest of several along the lower Anedeli, and an important waypoint in the tin trade. It prospered even as Watjubaga faded; the Empire was first reduced to its heartland of the Five Rivers, then into what was a minor kingdom in all but name. Lopitja declared its independence in 1080, establishing a nation of its own along the banks of the Anedeli. It became the capital of one of the several post-Imperial kingdoms which vied to inherit the mantle of the First Speakers’ authority; its main rivals were Gutjanal [Albury-Wodonga], Tjibarr [Swan Hill] and Yigutji [Wagga Wagga].

Lopitja’s favourable position along the Anedeli meant that it controlled the best transportation route for tin from the north. This was no longer a monopoly, since tin could also be imported from the distant Cider Isle [Tasmania], but it was still a valuable trade good. It was also close to the mines of Silver Hill, and its control over those lands added to its wealth.

For a brief flowering in the twelfth century, Lopitja was one of the two greatest post-Imperial kingdoms. Its main rival was Tjibarr, and the two kingdoms fought several wars throughout the century. Lopitja successfully defended itself during those wars. What its people did not know, however, was that their era of prominence was limited. The climate was reverting to its long-term norm of semi-aridity, and Lopitja’s place in the wet would be replaced by a more normal place in the sun – the endless heat of the outback sun, to be more precise.

In that brief time, though, Lopitja produced one man who had ideas which would change the world.

* * *

August 1145

House of the Spring Flowers

Kantji [Menindee, NSW], Kingdom of Lopitja

Some have called him the Good Man, although he never acknowledges when people speak to him by that title. Nor does he answer to the name his mother gave him. What is that but an arbitrary set of syllables? Some have called him the Teacher, and he will answer to that name, however reluctantly. He does not want to teach people; he wants to make them teach themselves.

He stands at the double bronze gates that mark the start of the Spiral Garden. The breeze blows out of the northwest, warming his cheeks with the breath of the endless desert. The wind carries the distinctive tang of blue-leaved mallee trees, a scent that for now overwhelms the myriad other aromas of the garden beyond these walls.

In the burnished bronze, the Teacher catches a glimpse of himself. Red-brown skin covers a face which no honest man would call handsome, and which is mercifully blurred in the imperfect reflection of metal. Wavy hair growing bushy and long on both sides of his face, black streaked with white. He is turning old, he knows, but that is all part of the Path on which any man finds himself, willing or not. It matters not what happens to a man, just how he bears himself while events happen.

The image in the burnished bronze reminds him, although he already knows, that his clothing is no different to that worn by any other gentleman of substance in the kingdom. It has to be. Rightly or wrongly, no-one would listen to a poor teacher, any more than they would seek treatment from a deformed doctor. So he wears the same black-collared tjiming which any high-status man would wear, fitting loose around his neck, long sleeves dangling beneath his arms, and the main bulk of the garment wrapped twice around his torso and held in place with an opal-studded sash, while the hem just covers his knees. Clothes are merely appearance, not substance, but a wise man knows when appearances matter.

Four other men cluster behind him, dressed in similar styles although without the ornateness of opals and sapphires. They think that he has brought them to the House of the Spring Flowers to reveal to them some great truth that is concealed within these walls of stone and timber and vegetation.

So, in a way, he is. But it is nothing like what they will be expecting. The carefully crafted forms of the House were built on a spot where, it is said, the Rainbow Serpent rested on his path down the Anedeli. This is meant to be a place of power, a place where a man can stand and feel himself growing closer to the Evertime. The gardens, the pools, the three fountains, are all meant to inspire that sense of serenity.

If only truth were so simple to find that a man could step in here and attain it!

He gestures, and three of the four would-be acolytes move to open the gates. The fourth man does not move, but keeps chewing on a lump of pituri. That man had offered the Teacher another ball of the stimulant a few moments before, and did not seem to understand why he declined the offer. Many men have claimed that using pituri or other drugs brings a man closer to the Evertime. For himself, though, he thinks that such drugs merely let the user hear the echoes in his own head.

He leads the men into the Spiral Garden. He moves at a quicker pace than they will be expecting; he pretends not to notice the occasional mumbles of the would-be acolytes behind him. The Garden is meant to be contemplated slowly, in a careful progression in ever-decreasing almost-circles until one reaches the centre.

The Teacher strides past the places of contemplation; he ignores the niches set into the walls, or the places where gum trees have been planted to provide shade for men to stand and savour the scenery. He walks alongside the stream that traces a path along the centre of the spiral, drawing water via underground passages from the Anedeli. Flowers bloom in a myriad of colours around him, desert flowers from the Red Lands to the far north and west which normally would blossom only in the aftermath of rare desert rains. Here, with irrigation water available, the flowers bloom according to the command of the gardeners. There is a lesson there, but not the one which he wants these men to consider today.

He leads them through almost all the Garden, then stops while they are not yet in sight of the central pond, although the sacred bunya trees [5] around that pond grow high enough that they show over the walls. When he stops, it is not to draw their attention to any of the arrangements of plants, but to speak to a gardener’s assistant who is methodically pruning one of the ironwood [Casuarina] trees.

The assistant pauses in his labour and says, “Good to see you, Teacher! Are you well, my friend?”

The Teacher says, “Yes, Gung, I am well.” He introduces each of the would-be acolytes in turn. Each time, the gardener’s assistant gives the same enthusiastic greeting, word for word the same except for the name of the person he is greeting. The acolytes respond to the enthusiasm that the assistant shows, saying their own greetings in a similar energetic tone.

The Teacher says, “We need to see more of the Garden. Stay well, Gung.”

The gardener’s assistant says, “You too. Have a good day, Teacher!” He offers similar farewells to each of the would-be acolytes, each of them the same except for the name.

The Teacher leads the would-be acolytes a short distance away. Far enough that they can talk without their voices carrying, but not so far that they lose sight of the gardener’s assistant. They watch as the assistant returns to his task of pruning the ironwood trees, cheerfully completing each step without supervision.

The Teacher says, “Gung is a man slow of wit, but sincere in his heart. If we go back and greet him in a few minutes, he will say the same thing as before, and greet each of us warmly, for he knows but little of how to speak. Yet he does his tasks as the gardeners give them, and will approach all of them in the same manner.”

He pauses, then continues, “So, is this man happier than the king? The king is burdened with worry, with our enemies in Tjibarr and Garrkimang threatening our borders. Yet this man knows little, and enjoys much.”

The would-be acolytes nod and murmur in agreement. “This man is happy, happier even than the king,” the pituri-chewing acolyte says.

The Teacher says, “So, if this man is happy, then, what makes him happy? It cannot be wealth, for this man has none.” As if carelessly, his fingers run over the sapphire-studded bracelet on his wrist. All of these acolytes know that the Teacher is wealthy, if not quite of the royal family. “It cannot be praise, for those who work with him neither praise him nor condemn him, but just expect him to work.”

“His joy must come from within, then,” one of the acolytes says.

“So, then, is joy something which comes from within?” the Teacher asks. “Is it intrinsic to a man, not something which can be granted from without?”

The acolytes nod again.

“Yet if this man were to be punished, condemned, shouted at, would he not feel sorrow? Would he not be deprived of happiness?”

“Maybe happiness comes from within, while unhappiness comes from without?” the pituri-chewing acolyte says.

“Perhaps,” the Teacher says. “Yet if a man is praised, would that not usually make him happy? If I were to say to you, “I am pleased with you,” would that not grant you a boon of joy?”

“It would be the honour of my day,” the pituri-chewer says.

“So, then, is joy something which can be found from within, or something which comes from without?”

The Teacher waits, but no-one answers him.

Eventually, he says, “Joy is neither internal nor external; it comes from bringing oneself into harmony with the world around. It need not even be a choice of enlightenment; a man who perceives as little as our gardeners’ assistant can still be abundantly joyful. It is the alignment, the convergence of one’s own desires with the present circumstances which matter. As circumstances change, as lives change, we must strive to keep ourselves aligned; we must make our own essence the balance on which our world shifts.”

* * *

The man whom allohistory would come to call the Good Man was born sometime around 1080; accounts differ as to whether he was born before or after Lopitja gained its independence. The place of his birth is recognised to be somewhere near Kantji, although there are several competing claims for the exact location. He was born into a reasonably wealthy family; his father is reported to have been a dealer in incenses and perfumes. A plethora of tales describe his life and his teachings, many of them undoubtedly apocryphal, but there is no doubt that in his lifetime he was regarded as a great philosopher, teacher, and visionary. Certainly, he spoke of the need to bring harmony to the cosmos, and of the Sevenfold Path which was the best means to achieve harmony. He was presumably a literate man, as most men of his background would have been, but no surviving letters or other writings can be indisputably attributed to him.

After the Good Man’s death in 1151, his disciples squabbled amongst themselves as to his legacy, and produced a variety of writings which purported to describe his teachings and philosophy. Over the next three decades, most of these disciples settled on a more-or-less accepted account of the Good Man’s life, teachings, and the path which should be followed. They came to be called the Pliri faith, from a word which can be roughly translated as “(the) Harmony.” This faith regarded the Good Man as a prophet-philosopher and ideal example of how a person should live, and its beliefs would spread most widely across the continent.

A smaller group of holdouts regarded the Good Man as a semi-divine figure, and over the next century emerged as a distinct sect who called themselves Tjarrling, a name which can be roughly translated as “the Heirs” or perhaps “the True Heirs.” Opinions differed on both sides of the religious divide as to whether the Tjarrling should be considered a separate religion or a branch of the Pliri faith; broadly speaking, most orthodox Pliri accepted the Tjarrling as misguided adherents of the same faith.

The Pliri faith became the first evangelical religion which the continent had seen. Its adherents created an organised priesthood, whose emphasis was on the continuity of faith and personal teaching from the Good Man to his disciples and to his priests. While they had a variety of religious writings, to the orthodox Pliri, these were treated as supplements to the continuity of learning from teacher to disciple to priest. They taught that following the Sevenfold Path and bringing balance to one’s own desires was the only way to achieve true harmony and concord throughout the cosmos. Other faiths and beliefs might have some truth, but they were not the whole truth, and so would thus inevitably bring discord. Only once all peoples followed the Sevenfold Path would there be complete harmony in the cosmos.

Missionaries and acolytes of the Pliri faith spread throughout the Five Rivers and beyond, and met with mixed receptions. They won a few converts, but the syncretic nature of many of the Gunnagalic beliefs meant that there was considerable resistance to the idea of one true path.

Pliri missionaries had their first major success in 1209, when the new king of Lopitja converted to the Pliri faith, and then in 1214 made it the state religion of his kingdom. Over the next few decades, the faith became deeply established in the kingdom. Unfortunately for its adherents, Lopitja itself was dying. The unusual climatic conditions which sustained the kingdom were fading. Papukurdna was drying up, and the winter rains were becoming more erratic. Farmers abandoned their fields, the population declined, and in time the kingdom lost its wars with Tjibarr. The capital was sacked in 1284, and most of its other cities were abandoned. Kantji returned to desert, its stone walls and roads now an empty haunt of wind-borne red dust, while the wonders of the Spiral Garden were reclaimed by desert scrubs.

By then, however, the Pliri faith had spread much further.

Within the Five Rivers itself, the Pliri faith never became a majority religion anywhere except the fading Lopitja kingdom. Some people converted to the religion, and temples were established which remained over the centuries. Yet the traditional view of religion gradually reasserted itself; the Good Man’s teachings were simply viewed as one path among many.

Orthodox Pliri teachings were brought by missionaries to the lower reaches of the Nyalananga. They had some success in converting the peoples there, particularly the Yadilli who dwelt south-east of the Nyalananga mouth. Their most important long-term success, however, came from the establishment of temples on the Island [Kangaroo Island], and the wholesale conversion of the Nangu in 1240. The Nangu embraced the Pliri faith, and as their trade network grew, the faith spread along with it.

The heterodox Tjarrling sect made little progress within the Five Rivers, but its displaced adherents carried their beliefs to the northern headwaters of the Anedeli. There, the Butjupa and Yalatji peoples [6] slowly converted to the new faith, and by the seventeenth century it had become almost universal among those peoples.

* * *

The Pliri faith has many competing schools and interpretations; there are written scriptures, but no universal agreement about what they mean. Above the level of an individual temple, there is no guiding central authority for the faith, no-one who can make absolute decisions. Some living priests become regarded as influential authorities who should be consulted, and the writings of some former priests have become the foundation of particular schools of thought.

However, the form which was adopted by the Nangu would be the most influential school of the Pliri faith. Like all of the schools, it was based on acceptance of the Sevenfold Path which was the core of the Good Man’s teachings. It also included considerable elements and influences from traditional Gunnagalic religion. For the Good Man had taken many religious concepts and other aspects of his worldview from the preceding Gunnagalic religions, and some others were inserted into the Pliri faith by his disciples and early converts.

At its core, the Pliri faith views the cosmos as a single connected entity. The actions of every person and every object are connected; nothing happens in isolation. There is no such thing as an inanimate object, for everything is seen as having the same “essence,” and both affects and is affected by everything else. All actions, great or small, good or bad, have their place in the pattern of the cosmos. Moreover, all actions have consequences; nothing which is done can be said to have no effect on the rest of the world. The most common analogy which the Good Man taught is of the cosmos being like a pond; anything which was cast into that pond would produce ripples.

According to the Good Man, the foundation of understanding came from recognising the truth of interconnectedness, and the effects of this truth. It is inevitable that actions will change the world, but the question is whether an action is dandiri (bringing harmony) or waal (bringing discord). Acting in a way which brings harmony is the foundation of all virtues and good things; acting in a way which brings discord is the foundation of all suffering, even if the influence is not obvious to the casual beholder.

The Good Man taught that the key to maximising harmony was to bring balance to one’s own desires, and align them with the broader cosmos. This meant that one should follow the Sevenfold Path. The Path was the only true way to bring oneself into harmony with the cosmos. Stepping off the Path unbalanced oneself and reduced harmony in the cosmos, which increased discord and suffering. Other faiths and beliefs might contain some similarities to the Path, and so some aspects of truth, but their correspondence was never perfect. So, to some degree every other faith increases the suffering and discord in the cosmos. If everything and everyone acts in harmony, then there will be balance. That will bring a minimum of suffering, and the maximum of solace.

The Sevenfold Path was divided into seven aspects, each of which should be followed by every person, at least as far as they are able to within their understanding and ability. The interpretation of these paths was coloured by individual societies and pre-existing religious beliefs, but the names of each of the paths was accepted throughout the Pliri faith.

The first path, the founding path, is the path of harmony. All people should act in a way which increases harmony, not in a way which causes discord. There is no universal list of the actions which create discord, but in general harmony can be increased by maintaining standards of courtesy, honesty, and respect for others. Honesty is not an absolute, at least according to some priests, but can be tolerated when a lie would be less hurtful. Theft and taking of other people’s property is condemned unless it is to avoid greater suffering. Violence is generally to be avoided, but it can become necessary if it is directed against something which would otherwise increase disharmony, such as social unrest, preventing murder or theft, and so on.

The second path is the path of propriety. This means that each person should act in a manner befitting their station in society; to do otherwise is to cause disharmony. Princes and slaves both should act as befits their role. A Nangu axiom restates this path as “to the merchant his profit, to the chief his obedience, to the artisan his craft, to the priest his prayers, and to the worker his duties.” This includes the implicit assumption that rulers who act in a manner befitting their status should be obeyed, while those who do not do so should be removed. It also means that workers, labour draftees, slaves and the common classes are expected to obey and serve, not seek to improve their station. There is an implicit hierarchy in a Pliri society, and there is not much expectation of social mobility in life. Since the Pliri faith inherited the old Gunnagalic beliefs in eternity and reincarnation, it is expected that people will live in different stations in different lives.

The third path is the path of decisiveness. This is often restated to mean “no half-actions.” The principle of balance and harmony means that inaction is often the best course; sometimes doing nothing is the best way to avoid causing discord. Conversely, when action is required, it is because something has been done to cause disharmony. In this case, decisive action is required, not half-measures.

For instance, the Pliri principle is that war should not be fought unless there is good reason. Most commonly, this is because a society is causing discord, or against social unrest. Such a war should be pursued to its utmost finish. Enemy soldiers should be hunted down and killed in decisive battles; prisoners should not be taken, quarter should not be given. Soldiers should not kill those who are not part of the war, but if someone makes himself a part of the war, then he should be killed without compunction. Likewise, rulers who live according to this path should ignore small slights; there is no need to respond to every complaint and insult. That would only provoke a cycle of retribution and cause endless discord. If action is required against an enemy of the realm, though, it should be swift, decisive, and without mercy [7].

The fourth path is the path of prayer. The Good Man viewed prayer as both a means of personal enlightenment – communing with the Evertime – and as a means of honour, respect and intercession with other beings. People are expected to pray to intercede with beings of power, such as the myriad of divine beings whose existence was accepted as an inheritance from older religions. People are also expected to pray to honour and respect both their ancestors and their descendants. (The inherited view of time means that the distinction between ancestors and descendants is blurred.)

For common people, the orthodox faith has standardised the time of daily prayers as dawn and dusk. These are called the half-times, when there is balance between day and night, and when prayers are most efficacious. Other important times for prayer are at the times of the half-moon (both waxing and waning), and especially the equinoxes, which are seen as the focal points of the year. The orthodox Pliri calendar starts with a great religious festival at the spring equinox, as an ideal time of balance. Priests are expected to spend much of their lives in prayer, since this will increase harmony and preserve the balance of the cosmos.

The fifth path is the path of charity. The Good Man taught of the need to support and care for others. On the Island, the Nangu traditionally interpret this as requiring a donation of an twelfth of their income to support others; other Pliri nations usually just expect generosity and helpfulness rather than a specific amount. In most cases, this path is followed by donating to the temples, which in turn are expected to support the poor, sick and hungry. Rulers are likewise expected to be generous; earning wealth is perfectly acceptable, but hoarding it while people starve is not.

The sixth path is the path of acceptance. The Good Man taught that the cosmos is larger than any individual; sometimes, no matter what a man’s deeds might be, there are larger forces at work which he cannot control. In this case, while a man should do the best he can, he should not express frustration or condemn himself for things which cannot be changed. He should simply accept some things as inevitable, abandon futile striving which will only bring about further discord, and focus his attention on those duties which he can perform. In common practice, this is interpreted to mean avoidance of complaining about outcomes, perceived poor fortune, bad luck, or the like. It is appropriate to advise others on when their actions may be increasing discord, but not to complain about one’s own status or present condition.

The seventh path is the path of understanding. The Good Man taught that each person should strive to understand themselves and the cosmos as they really are, not through misunderstandings or illusions. They should achieve this knowledge both through self-reflection and through instruction from those who have achieved greater understanding. In common practice, this means that a person should seek the guidance of their parents or other elder relatives to assist in understanding their daily lives. To understand the broader cosmos, they should seek the guidance of their priests or the written teachings of revered teachers, who can help to build their proper knowledge. Priests can guide people and help them to recognise the effects of their own actions, and thus better follow all aspects of the Sevenfold Path.

While they are not strictly part of the teachings of the Sevenfold Path, there are also other beliefs which have become integral parts of the Pliri faith. Most of these beliefs were derived from the traditional Gunnagalic religious milieu. These include the existence of a great many divine beings, heroic figures, and other spiritual figures which are part of the cosmos. These can be prayed to, negotiated with, and in some cases consulted to gain greater understanding. However, the Good Man taught that none of these beings were infallible or all-knowing; they were merely powerful beings.

Likewise, the Pliri faith accepts the idea of the Evertime, of the eternal nature of the cosmos, and of reincarnation. However, reincarnation has been somewhat reinterpreted. In traditional Gunnagalic religion, reincarnation could be into a variety of forms, human, animal, or plant. The Pliri faith recognises only reincarnation in human form, and teaches that people are reborn into different bodies and stations as part of the overall balance of the cosmos. Reincarnation is not based just on an individual’s own actions, but on the broader principles of harmony and discord. Everyone will be influenced by the cosmos.

* * *

In 1618, the Pliri faith is the one multinational faith on the continent. Some peoples have religions of state, such as the Atjuntja and the Yadji. There are some traditional syncretic religions which are widespread over some areas, particularly the Five Rivers.

However, the Pliri faith is the one faith which explicitly tries to convert other peoples, and its adherents have slowly become more numerous and more widespread, with even a few converts in Aotearoa [New Zealand]. The Atjuntja kill converts amongst their own subject peoples, the Yadji persecute them, and some other Gunnagalic peoples spurn them.

The Pliri faith is still slowly growing. This is not least because once a population has become majority Pliri, they are very unlikely to revert to other faiths. This is part of the Pliri teaching that other religions increase discord and suffering; any would-be converts are discouraged through passive or active means. Pliri peoples are also inclined to speak out against their own people if they believe that a particular person is not living according to the Path. After all, anyone who steps off the Path is, in their way, increasing the suffering of others.

Still, after 1618, the Pliri faith will have deal with a religious challenge greater than any which it has so far experienced...

* * *

[1] The Five Rivers are the Nyalananga [Murray], Anedeli [Darling], Matjidi [Murrumbidgee], Gurrnyal [Lachlan] and Pulanatji [Macquarie].

[2] Bountiful rains by Australian standards, that is. The rainfall in this period still only averages between 300-400 mm. It is more reliable than the usual Australian weather, though; droughts have been reduced in both frequency and duration.

[3] This climate shift occurs within the same broad timeframe as the Medieval Warm Period (roughly 900-1300 AD). Around the North Atlantic, this climatic shift produced generally warmer temperatures. It lasted for varying time periods and had different effects in other parts of the globe; parts of the tropical Pacific seem to have been cool and dry, as was the Antarctic Peninsula. In Australia, the weather was affected by a long-term La Niña phenomenon, which produced generally cooler temperatures and increased rainfall. It is unclear just how much the climate shifted, since climate records in Australia are sparse, but Lake Eyre held permanent water for what seems to have been at least two centuries, and probably longer. The climate reverted to a drier phase by the end of the Medieval Warm Period, possibly earlier.

[4] Bush pears (Marsdenia australis) and desert raisins (Solanum centrale) are fruits grown on vines and shrubs suited to semi-arid conditions. Blue-leaved mallee (Eucalyptus polybractea) is one of many Australian eucalypt species. It is native to semiarid regions such as along the Darling, and its leaves contain high concentrations of eucalyptus oil which make them useful as a flavouring.

[5] The bunya tree (Araucaria bidwillii), popularly but somewhat inaccurately called bunya pine, is a kind of conifer which in its wild state is restricted to small areas in the Bunya Mountains and a few other parts of Queensland. It produces erratic but large yields of edible seeds which were much appreciated by Aboriginal peoples; in the years when bunyas produced seeds, large gatherings of people would congregate to feast on the seeds. Bunya trees can be grown in cultivation over a fairly wide area, although they need a reasonable amount of water. In allohistorical Australia, bunya trees are also revered as sacred, although they are mostly grown on the eastern seaboard. In the inland areas, they can only be grown if supported by irrigation.

[6] The Buputja live in historical northern New South Wales west of the New England tablelands. The Yalatji live in the historical Darling Downs, among the headwaters of the eponymous river.

[7] Orthodox Pliri priests would be right alongside Machiavelli’s adage of never doing an enemy a small injury, although he would not necessarily have agreed with their idea of fighting wars without taking prisoners.

* * *

Thoughts?

P.S. From here, there are two more posts coming up about the culture of *Australia in 1618. One post will be on Tjibarr, the kingdom along the *Murray, although that post may be long enough to be split into two. The other post will be on the Daluming kingdom, on the east coast. After that, I’ll be moving on to posts about European contact with *Australia (initially the Dutch). At some point, I’ll also give an overview of the Maori in *New Zealand, but it’s taking a while to work out the details of that culture, so I’ll move on to showing European contact first.

In Australia, the driest of inhabited continents, water means life. Droughts are common, and even when rain does fall, it often does so in such abundance that floods are the end result. The irregularity of this rain is most pronounced in the interior, and naturally enough most of the inhabitants of the continent live nearer the coast. The outback – the red heart of the continent – is nearly devoid of water, and nearly devoid of human life.

In eastern Australia, the frontier between the outback and the settled districts is traditionally the River Darling. Rising in the mountain ranges of southern Queensland, the Darling drains a large part of the continent before emptying into the River Murray. The Darling is an extremely irregular river, often drying up completely, and at other times flooding so prodigiously that the waters can take six months to recede. Nonetheless, it became an important transport route during the early days of European settlement of Australia.

Beyond the Darling lies the red heart, the outback. The nearest part of this is called the Channel Country, a series of ancient flood plains marked by the courses of many dried up rivers. Rain seldom falls here, but when it does, it floods along these channels and drains into Lake Eyre, the largest lake in Australia, and which has no outlet to the sea. Most of the time, Lake Eyre is a flat, dry salt plain, but sometimes the rains from distant cyclones or monsoons fill the lake. When it does, fish spawn in great abundance, and waterbirds gather from across the vast interior to feed and breed by the shores. The lake dries out soon enough, the fish dying, the waterbirds moving on, and its bed reverts to a salt plain.

In the cyclically dry country beyond the Darling, Europeans found relatively little to interest them. Some rich mineral lodes have been mined, and sheep and cattle graze in stations (farms) which need very large areas to support their herds on the sparse vegetation, but otherwise the country is mostly empty.

In allohistorical Australia, the same river is called the Anedeli. To the Gunnagalic peoples who developed agriculture along the Nyalananga [River Murray], the Anedeli was for a very long time considered a frontier. The lower reaches of the Anedeli drained through country where the rainfall was extremely limited and agriculture almost impossible. In time, migrants used the Anedeli as a transportation route, following its course to the upper reaches. Here, they found more fertile country and a variety of mineral wealth – especially tin – which meant that the Anedeli became a much more important transportation route.

As Gunnagalic civilization developed over the centuries, they came to regard the Anedeli as one of the Five Rivers that watered the known world [1]. An empire arose, Watjubaga, which took its name from the Five Rivers which flowed through the heart of its territory. Four of those rivers had long-established cities and verdant agriculture and aquaculture along their banks. The fifth river, the Anedeli, continued to be used primarily as a transportation route, and it marked a frontier rather than a source of life.

To the Gunnagalic peoples, the country beyond the Anedeli was called the Red Lands, or the Hot Lands, or the Dry Country. They did have a few uses for it. Silver Hill [Broken Hill] gave them a rich source of silver, lead and zinc, and other mines gave them some valuable metals and minerals, especially varieties of ochre which they used for dyes. They sometimes mined salt and gypsum from the dry lake beds, and collected a few flavourings and fibres from some of the outback plants. For the most part, though, the Red Lands were a thinly-settled frontier fading into desert which was occupied only by sometimes hostile hunter-gatherer peoples.

Usually.

For the Red Lands had a brief flowering of more reliable agriculture, a time when the Anedeli became not a frontier but a treasured source of water for peoples who lived along its banks. Thanks to a rare shift in the climate, the rainfall along the lower Anedeli became sufficient enough to support several substantial cities and a separate kingdom. This time of flowering would come to an end, with the yams and wattles withering for lack of water and the cities abandoned to the desert. In that brief time, though, the kingdom beside the Anedeli witnessed the birth of the first evangelical religion on the continent; a new faith which would in time spread far beyond its shores...

* * *

At the turn of the tenth century AD, during the decline of the Watjubaga Empire, imperial authority was dying outside of the heartland of the Five Rivers. The Bungudjimay in the northeast had defeated imperial armies and were starting to raid the fringes of the tin and sapphire-producing regions of the north. In the east, the Patjimunra had just declared their independence from imperial authority. The Junditmara in the south were rising in perpetual rebellion, and the imperial governors were powerless to stop them.

In the midst of this chaos, it took some time for the imperial administration at Garrkimang [Narrandera] to notice a remarkable shift in the climate. The lands around the Anedeli had always been dry and barely worth farming. Yet over the last few decades, the usual winter rains had been heavier than usual, and reached further and further north. Summers and winters both had grown somewhat cooler, but not intolerably so. Any minor inconvenience that the colder temperatures caused was more than offset by the prospect of bountiful rains falling year after year [2].

Just after the turn of the century, news reached Garrkimang of another remarkable change. They knew, of course, of the distant salt bed that they called Papukurdna [Lake Eyre], and of the cycle of refilling and evaporation. Most of their salt came from smaller dry lakes, but they had sufficient contact with the hunter-gatherer peoples of the interior to hear about this greatest of dry lakes. Tales from these peoples, and confirmed by ‘civilized’ visitors, confirmed the extraordinary tale that this great lake had filled permanently, or so it seemed.

The years turned, with rebellions and defeats plaguing Watjubaga, yet still visitors reported that the former dry lake remained full. The heavier winter rains continued over the frontier of the River Anedeli and the Red Lands it bordered. In time, the existence of these heavier rains came to be seen as the natural state of affairs. In 912, then-First Speaker [Emperor] Lopitja announced the founding of a new city along the Anedeli, modestly named after himself. Farmers started to settle the lands around this new city of Lopitja [Wilcannia, New South Wales]. In time, most people forgot that this country had for so long been arid and too hostile to support agriculture [3].

The decades passed, and the Red Lands along the Anedeli became almost as well-populated as any other part of the Five Rivers. Yams and wattles flourished with the rains, and the expansion into this region gave them access to crops which had not been domesticated further south; bush pears and bush raisins as fruits and flavourings, and trees such as blue-leaved mallee as a spice [4]. They were not able to build artificial wetlands in quite the same way as on the other main rivers, but they did build some artificial lakes which could store Anedeli floodwaters and allow both fishing and irrigation.

Lopitja became a flourishing city, the largest of several along the lower Anedeli, and an important waypoint in the tin trade. It prospered even as Watjubaga faded; the Empire was first reduced to its heartland of the Five Rivers, then into what was a minor kingdom in all but name. Lopitja declared its independence in 1080, establishing a nation of its own along the banks of the Anedeli. It became the capital of one of the several post-Imperial kingdoms which vied to inherit the mantle of the First Speakers’ authority; its main rivals were Gutjanal [Albury-Wodonga], Tjibarr [Swan Hill] and Yigutji [Wagga Wagga].

Lopitja’s favourable position along the Anedeli meant that it controlled the best transportation route for tin from the north. This was no longer a monopoly, since tin could also be imported from the distant Cider Isle [Tasmania], but it was still a valuable trade good. It was also close to the mines of Silver Hill, and its control over those lands added to its wealth.

For a brief flowering in the twelfth century, Lopitja was one of the two greatest post-Imperial kingdoms. Its main rival was Tjibarr, and the two kingdoms fought several wars throughout the century. Lopitja successfully defended itself during those wars. What its people did not know, however, was that their era of prominence was limited. The climate was reverting to its long-term norm of semi-aridity, and Lopitja’s place in the wet would be replaced by a more normal place in the sun – the endless heat of the outback sun, to be more precise.

In that brief time, though, Lopitja produced one man who had ideas which would change the world.

* * *

August 1145

House of the Spring Flowers

Kantji [Menindee, NSW], Kingdom of Lopitja

Some have called him the Good Man, although he never acknowledges when people speak to him by that title. Nor does he answer to the name his mother gave him. What is that but an arbitrary set of syllables? Some have called him the Teacher, and he will answer to that name, however reluctantly. He does not want to teach people; he wants to make them teach themselves.

He stands at the double bronze gates that mark the start of the Spiral Garden. The breeze blows out of the northwest, warming his cheeks with the breath of the endless desert. The wind carries the distinctive tang of blue-leaved mallee trees, a scent that for now overwhelms the myriad other aromas of the garden beyond these walls.

In the burnished bronze, the Teacher catches a glimpse of himself. Red-brown skin covers a face which no honest man would call handsome, and which is mercifully blurred in the imperfect reflection of metal. Wavy hair growing bushy and long on both sides of his face, black streaked with white. He is turning old, he knows, but that is all part of the Path on which any man finds himself, willing or not. It matters not what happens to a man, just how he bears himself while events happen.

The image in the burnished bronze reminds him, although he already knows, that his clothing is no different to that worn by any other gentleman of substance in the kingdom. It has to be. Rightly or wrongly, no-one would listen to a poor teacher, any more than they would seek treatment from a deformed doctor. So he wears the same black-collared tjiming which any high-status man would wear, fitting loose around his neck, long sleeves dangling beneath his arms, and the main bulk of the garment wrapped twice around his torso and held in place with an opal-studded sash, while the hem just covers his knees. Clothes are merely appearance, not substance, but a wise man knows when appearances matter.

Four other men cluster behind him, dressed in similar styles although without the ornateness of opals and sapphires. They think that he has brought them to the House of the Spring Flowers to reveal to them some great truth that is concealed within these walls of stone and timber and vegetation.

So, in a way, he is. But it is nothing like what they will be expecting. The carefully crafted forms of the House were built on a spot where, it is said, the Rainbow Serpent rested on his path down the Anedeli. This is meant to be a place of power, a place where a man can stand and feel himself growing closer to the Evertime. The gardens, the pools, the three fountains, are all meant to inspire that sense of serenity.

If only truth were so simple to find that a man could step in here and attain it!

He gestures, and three of the four would-be acolytes move to open the gates. The fourth man does not move, but keeps chewing on a lump of pituri. That man had offered the Teacher another ball of the stimulant a few moments before, and did not seem to understand why he declined the offer. Many men have claimed that using pituri or other drugs brings a man closer to the Evertime. For himself, though, he thinks that such drugs merely let the user hear the echoes in his own head.

He leads the men into the Spiral Garden. He moves at a quicker pace than they will be expecting; he pretends not to notice the occasional mumbles of the would-be acolytes behind him. The Garden is meant to be contemplated slowly, in a careful progression in ever-decreasing almost-circles until one reaches the centre.

The Teacher strides past the places of contemplation; he ignores the niches set into the walls, or the places where gum trees have been planted to provide shade for men to stand and savour the scenery. He walks alongside the stream that traces a path along the centre of the spiral, drawing water via underground passages from the Anedeli. Flowers bloom in a myriad of colours around him, desert flowers from the Red Lands to the far north and west which normally would blossom only in the aftermath of rare desert rains. Here, with irrigation water available, the flowers bloom according to the command of the gardeners. There is a lesson there, but not the one which he wants these men to consider today.

He leads them through almost all the Garden, then stops while they are not yet in sight of the central pond, although the sacred bunya trees [5] around that pond grow high enough that they show over the walls. When he stops, it is not to draw their attention to any of the arrangements of plants, but to speak to a gardener’s assistant who is methodically pruning one of the ironwood [Casuarina] trees.

The assistant pauses in his labour and says, “Good to see you, Teacher! Are you well, my friend?”

The Teacher says, “Yes, Gung, I am well.” He introduces each of the would-be acolytes in turn. Each time, the gardener’s assistant gives the same enthusiastic greeting, word for word the same except for the name of the person he is greeting. The acolytes respond to the enthusiasm that the assistant shows, saying their own greetings in a similar energetic tone.

The Teacher says, “We need to see more of the Garden. Stay well, Gung.”

The gardener’s assistant says, “You too. Have a good day, Teacher!” He offers similar farewells to each of the would-be acolytes, each of them the same except for the name.

The Teacher leads the would-be acolytes a short distance away. Far enough that they can talk without their voices carrying, but not so far that they lose sight of the gardener’s assistant. They watch as the assistant returns to his task of pruning the ironwood trees, cheerfully completing each step without supervision.

The Teacher says, “Gung is a man slow of wit, but sincere in his heart. If we go back and greet him in a few minutes, he will say the same thing as before, and greet each of us warmly, for he knows but little of how to speak. Yet he does his tasks as the gardeners give them, and will approach all of them in the same manner.”

He pauses, then continues, “So, is this man happier than the king? The king is burdened with worry, with our enemies in Tjibarr and Garrkimang threatening our borders. Yet this man knows little, and enjoys much.”

The would-be acolytes nod and murmur in agreement. “This man is happy, happier even than the king,” the pituri-chewing acolyte says.

The Teacher says, “So, if this man is happy, then, what makes him happy? It cannot be wealth, for this man has none.” As if carelessly, his fingers run over the sapphire-studded bracelet on his wrist. All of these acolytes know that the Teacher is wealthy, if not quite of the royal family. “It cannot be praise, for those who work with him neither praise him nor condemn him, but just expect him to work.”

“His joy must come from within, then,” one of the acolytes says.

“So, then, is joy something which comes from within?” the Teacher asks. “Is it intrinsic to a man, not something which can be granted from without?”

The acolytes nod again.

“Yet if this man were to be punished, condemned, shouted at, would he not feel sorrow? Would he not be deprived of happiness?”

“Maybe happiness comes from within, while unhappiness comes from without?” the pituri-chewing acolyte says.

“Perhaps,” the Teacher says. “Yet if a man is praised, would that not usually make him happy? If I were to say to you, “I am pleased with you,” would that not grant you a boon of joy?”

“It would be the honour of my day,” the pituri-chewer says.

“So, then, is joy something which can be found from within, or something which comes from without?”

The Teacher waits, but no-one answers him.

Eventually, he says, “Joy is neither internal nor external; it comes from bringing oneself into harmony with the world around. It need not even be a choice of enlightenment; a man who perceives as little as our gardeners’ assistant can still be abundantly joyful. It is the alignment, the convergence of one’s own desires with the present circumstances which matter. As circumstances change, as lives change, we must strive to keep ourselves aligned; we must make our own essence the balance on which our world shifts.”

* * *

The man whom allohistory would come to call the Good Man was born sometime around 1080; accounts differ as to whether he was born before or after Lopitja gained its independence. The place of his birth is recognised to be somewhere near Kantji, although there are several competing claims for the exact location. He was born into a reasonably wealthy family; his father is reported to have been a dealer in incenses and perfumes. A plethora of tales describe his life and his teachings, many of them undoubtedly apocryphal, but there is no doubt that in his lifetime he was regarded as a great philosopher, teacher, and visionary. Certainly, he spoke of the need to bring harmony to the cosmos, and of the Sevenfold Path which was the best means to achieve harmony. He was presumably a literate man, as most men of his background would have been, but no surviving letters or other writings can be indisputably attributed to him.

After the Good Man’s death in 1151, his disciples squabbled amongst themselves as to his legacy, and produced a variety of writings which purported to describe his teachings and philosophy. Over the next three decades, most of these disciples settled on a more-or-less accepted account of the Good Man’s life, teachings, and the path which should be followed. They came to be called the Pliri faith, from a word which can be roughly translated as “(the) Harmony.” This faith regarded the Good Man as a prophet-philosopher and ideal example of how a person should live, and its beliefs would spread most widely across the continent.

A smaller group of holdouts regarded the Good Man as a semi-divine figure, and over the next century emerged as a distinct sect who called themselves Tjarrling, a name which can be roughly translated as “the Heirs” or perhaps “the True Heirs.” Opinions differed on both sides of the religious divide as to whether the Tjarrling should be considered a separate religion or a branch of the Pliri faith; broadly speaking, most orthodox Pliri accepted the Tjarrling as misguided adherents of the same faith.

The Pliri faith became the first evangelical religion which the continent had seen. Its adherents created an organised priesthood, whose emphasis was on the continuity of faith and personal teaching from the Good Man to his disciples and to his priests. While they had a variety of religious writings, to the orthodox Pliri, these were treated as supplements to the continuity of learning from teacher to disciple to priest. They taught that following the Sevenfold Path and bringing balance to one’s own desires was the only way to achieve true harmony and concord throughout the cosmos. Other faiths and beliefs might have some truth, but they were not the whole truth, and so would thus inevitably bring discord. Only once all peoples followed the Sevenfold Path would there be complete harmony in the cosmos.

Missionaries and acolytes of the Pliri faith spread throughout the Five Rivers and beyond, and met with mixed receptions. They won a few converts, but the syncretic nature of many of the Gunnagalic beliefs meant that there was considerable resistance to the idea of one true path.

Pliri missionaries had their first major success in 1209, when the new king of Lopitja converted to the Pliri faith, and then in 1214 made it the state religion of his kingdom. Over the next few decades, the faith became deeply established in the kingdom. Unfortunately for its adherents, Lopitja itself was dying. The unusual climatic conditions which sustained the kingdom were fading. Papukurdna was drying up, and the winter rains were becoming more erratic. Farmers abandoned their fields, the population declined, and in time the kingdom lost its wars with Tjibarr. The capital was sacked in 1284, and most of its other cities were abandoned. Kantji returned to desert, its stone walls and roads now an empty haunt of wind-borne red dust, while the wonders of the Spiral Garden were reclaimed by desert scrubs.

By then, however, the Pliri faith had spread much further.

Within the Five Rivers itself, the Pliri faith never became a majority religion anywhere except the fading Lopitja kingdom. Some people converted to the religion, and temples were established which remained over the centuries. Yet the traditional view of religion gradually reasserted itself; the Good Man’s teachings were simply viewed as one path among many.

Orthodox Pliri teachings were brought by missionaries to the lower reaches of the Nyalananga. They had some success in converting the peoples there, particularly the Yadilli who dwelt south-east of the Nyalananga mouth. Their most important long-term success, however, came from the establishment of temples on the Island [Kangaroo Island], and the wholesale conversion of the Nangu in 1240. The Nangu embraced the Pliri faith, and as their trade network grew, the faith spread along with it.

The heterodox Tjarrling sect made little progress within the Five Rivers, but its displaced adherents carried their beliefs to the northern headwaters of the Anedeli. There, the Butjupa and Yalatji peoples [6] slowly converted to the new faith, and by the seventeenth century it had become almost universal among those peoples.

* * *

The Pliri faith has many competing schools and interpretations; there are written scriptures, but no universal agreement about what they mean. Above the level of an individual temple, there is no guiding central authority for the faith, no-one who can make absolute decisions. Some living priests become regarded as influential authorities who should be consulted, and the writings of some former priests have become the foundation of particular schools of thought.

However, the form which was adopted by the Nangu would be the most influential school of the Pliri faith. Like all of the schools, it was based on acceptance of the Sevenfold Path which was the core of the Good Man’s teachings. It also included considerable elements and influences from traditional Gunnagalic religion. For the Good Man had taken many religious concepts and other aspects of his worldview from the preceding Gunnagalic religions, and some others were inserted into the Pliri faith by his disciples and early converts.

At its core, the Pliri faith views the cosmos as a single connected entity. The actions of every person and every object are connected; nothing happens in isolation. There is no such thing as an inanimate object, for everything is seen as having the same “essence,” and both affects and is affected by everything else. All actions, great or small, good or bad, have their place in the pattern of the cosmos. Moreover, all actions have consequences; nothing which is done can be said to have no effect on the rest of the world. The most common analogy which the Good Man taught is of the cosmos being like a pond; anything which was cast into that pond would produce ripples.

According to the Good Man, the foundation of understanding came from recognising the truth of interconnectedness, and the effects of this truth. It is inevitable that actions will change the world, but the question is whether an action is dandiri (bringing harmony) or waal (bringing discord). Acting in a way which brings harmony is the foundation of all virtues and good things; acting in a way which brings discord is the foundation of all suffering, even if the influence is not obvious to the casual beholder.

The Good Man taught that the key to maximising harmony was to bring balance to one’s own desires, and align them with the broader cosmos. This meant that one should follow the Sevenfold Path. The Path was the only true way to bring oneself into harmony with the cosmos. Stepping off the Path unbalanced oneself and reduced harmony in the cosmos, which increased discord and suffering. Other faiths and beliefs might contain some similarities to the Path, and so some aspects of truth, but their correspondence was never perfect. So, to some degree every other faith increases the suffering and discord in the cosmos. If everything and everyone acts in harmony, then there will be balance. That will bring a minimum of suffering, and the maximum of solace.

The Sevenfold Path was divided into seven aspects, each of which should be followed by every person, at least as far as they are able to within their understanding and ability. The interpretation of these paths was coloured by individual societies and pre-existing religious beliefs, but the names of each of the paths was accepted throughout the Pliri faith.

The first path, the founding path, is the path of harmony. All people should act in a way which increases harmony, not in a way which causes discord. There is no universal list of the actions which create discord, but in general harmony can be increased by maintaining standards of courtesy, honesty, and respect for others. Honesty is not an absolute, at least according to some priests, but can be tolerated when a lie would be less hurtful. Theft and taking of other people’s property is condemned unless it is to avoid greater suffering. Violence is generally to be avoided, but it can become necessary if it is directed against something which would otherwise increase disharmony, such as social unrest, preventing murder or theft, and so on.

The second path is the path of propriety. This means that each person should act in a manner befitting their station in society; to do otherwise is to cause disharmony. Princes and slaves both should act as befits their role. A Nangu axiom restates this path as “to the merchant his profit, to the chief his obedience, to the artisan his craft, to the priest his prayers, and to the worker his duties.” This includes the implicit assumption that rulers who act in a manner befitting their status should be obeyed, while those who do not do so should be removed. It also means that workers, labour draftees, slaves and the common classes are expected to obey and serve, not seek to improve their station. There is an implicit hierarchy in a Pliri society, and there is not much expectation of social mobility in life. Since the Pliri faith inherited the old Gunnagalic beliefs in eternity and reincarnation, it is expected that people will live in different stations in different lives.

The third path is the path of decisiveness. This is often restated to mean “no half-actions.” The principle of balance and harmony means that inaction is often the best course; sometimes doing nothing is the best way to avoid causing discord. Conversely, when action is required, it is because something has been done to cause disharmony. In this case, decisive action is required, not half-measures.

For instance, the Pliri principle is that war should not be fought unless there is good reason. Most commonly, this is because a society is causing discord, or against social unrest. Such a war should be pursued to its utmost finish. Enemy soldiers should be hunted down and killed in decisive battles; prisoners should not be taken, quarter should not be given. Soldiers should not kill those who are not part of the war, but if someone makes himself a part of the war, then he should be killed without compunction. Likewise, rulers who live according to this path should ignore small slights; there is no need to respond to every complaint and insult. That would only provoke a cycle of retribution and cause endless discord. If action is required against an enemy of the realm, though, it should be swift, decisive, and without mercy [7].

The fourth path is the path of prayer. The Good Man viewed prayer as both a means of personal enlightenment – communing with the Evertime – and as a means of honour, respect and intercession with other beings. People are expected to pray to intercede with beings of power, such as the myriad of divine beings whose existence was accepted as an inheritance from older religions. People are also expected to pray to honour and respect both their ancestors and their descendants. (The inherited view of time means that the distinction between ancestors and descendants is blurred.)

For common people, the orthodox faith has standardised the time of daily prayers as dawn and dusk. These are called the half-times, when there is balance between day and night, and when prayers are most efficacious. Other important times for prayer are at the times of the half-moon (both waxing and waning), and especially the equinoxes, which are seen as the focal points of the year. The orthodox Pliri calendar starts with a great religious festival at the spring equinox, as an ideal time of balance. Priests are expected to spend much of their lives in prayer, since this will increase harmony and preserve the balance of the cosmos.

The fifth path is the path of charity. The Good Man taught of the need to support and care for others. On the Island, the Nangu traditionally interpret this as requiring a donation of an twelfth of their income to support others; other Pliri nations usually just expect generosity and helpfulness rather than a specific amount. In most cases, this path is followed by donating to the temples, which in turn are expected to support the poor, sick and hungry. Rulers are likewise expected to be generous; earning wealth is perfectly acceptable, but hoarding it while people starve is not.

The sixth path is the path of acceptance. The Good Man taught that the cosmos is larger than any individual; sometimes, no matter what a man’s deeds might be, there are larger forces at work which he cannot control. In this case, while a man should do the best he can, he should not express frustration or condemn himself for things which cannot be changed. He should simply accept some things as inevitable, abandon futile striving which will only bring about further discord, and focus his attention on those duties which he can perform. In common practice, this is interpreted to mean avoidance of complaining about outcomes, perceived poor fortune, bad luck, or the like. It is appropriate to advise others on when their actions may be increasing discord, but not to complain about one’s own status or present condition.

The seventh path is the path of understanding. The Good Man taught that each person should strive to understand themselves and the cosmos as they really are, not through misunderstandings or illusions. They should achieve this knowledge both through self-reflection and through instruction from those who have achieved greater understanding. In common practice, this means that a person should seek the guidance of their parents or other elder relatives to assist in understanding their daily lives. To understand the broader cosmos, they should seek the guidance of their priests or the written teachings of revered teachers, who can help to build their proper knowledge. Priests can guide people and help them to recognise the effects of their own actions, and thus better follow all aspects of the Sevenfold Path.

While they are not strictly part of the teachings of the Sevenfold Path, there are also other beliefs which have become integral parts of the Pliri faith. Most of these beliefs were derived from the traditional Gunnagalic religious milieu. These include the existence of a great many divine beings, heroic figures, and other spiritual figures which are part of the cosmos. These can be prayed to, negotiated with, and in some cases consulted to gain greater understanding. However, the Good Man taught that none of these beings were infallible or all-knowing; they were merely powerful beings.

Likewise, the Pliri faith accepts the idea of the Evertime, of the eternal nature of the cosmos, and of reincarnation. However, reincarnation has been somewhat reinterpreted. In traditional Gunnagalic religion, reincarnation could be into a variety of forms, human, animal, or plant. The Pliri faith recognises only reincarnation in human form, and teaches that people are reborn into different bodies and stations as part of the overall balance of the cosmos. Reincarnation is not based just on an individual’s own actions, but on the broader principles of harmony and discord. Everyone will be influenced by the cosmos.

* * *

In 1618, the Pliri faith is the one multinational faith on the continent. Some peoples have religions of state, such as the Atjuntja and the Yadji. There are some traditional syncretic religions which are widespread over some areas, particularly the Five Rivers.

However, the Pliri faith is the one faith which explicitly tries to convert other peoples, and its adherents have slowly become more numerous and more widespread, with even a few converts in Aotearoa [New Zealand]. The Atjuntja kill converts amongst their own subject peoples, the Yadji persecute them, and some other Gunnagalic peoples spurn them.

The Pliri faith is still slowly growing. This is not least because once a population has become majority Pliri, they are very unlikely to revert to other faiths. This is part of the Pliri teaching that other religions increase discord and suffering; any would-be converts are discouraged through passive or active means. Pliri peoples are also inclined to speak out against their own people if they believe that a particular person is not living according to the Path. After all, anyone who steps off the Path is, in their way, increasing the suffering of others.

Still, after 1618, the Pliri faith will have deal with a religious challenge greater than any which it has so far experienced...

* * *

[1] The Five Rivers are the Nyalananga [Murray], Anedeli [Darling], Matjidi [Murrumbidgee], Gurrnyal [Lachlan] and Pulanatji [Macquarie].

[2] Bountiful rains by Australian standards, that is. The rainfall in this period still only averages between 300-400 mm. It is more reliable than the usual Australian weather, though; droughts have been reduced in both frequency and duration.

[3] This climate shift occurs within the same broad timeframe as the Medieval Warm Period (roughly 900-1300 AD). Around the North Atlantic, this climatic shift produced generally warmer temperatures. It lasted for varying time periods and had different effects in other parts of the globe; parts of the tropical Pacific seem to have been cool and dry, as was the Antarctic Peninsula. In Australia, the weather was affected by a long-term La Niña phenomenon, which produced generally cooler temperatures and increased rainfall. It is unclear just how much the climate shifted, since climate records in Australia are sparse, but Lake Eyre held permanent water for what seems to have been at least two centuries, and probably longer. The climate reverted to a drier phase by the end of the Medieval Warm Period, possibly earlier.

[4] Bush pears (Marsdenia australis) and desert raisins (Solanum centrale) are fruits grown on vines and shrubs suited to semi-arid conditions. Blue-leaved mallee (Eucalyptus polybractea) is one of many Australian eucalypt species. It is native to semiarid regions such as along the Darling, and its leaves contain high concentrations of eucalyptus oil which make them useful as a flavouring.

[5] The bunya tree (Araucaria bidwillii), popularly but somewhat inaccurately called bunya pine, is a kind of conifer which in its wild state is restricted to small areas in the Bunya Mountains and a few other parts of Queensland. It produces erratic but large yields of edible seeds which were much appreciated by Aboriginal peoples; in the years when bunyas produced seeds, large gatherings of people would congregate to feast on the seeds. Bunya trees can be grown in cultivation over a fairly wide area, although they need a reasonable amount of water. In allohistorical Australia, bunya trees are also revered as sacred, although they are mostly grown on the eastern seaboard. In the inland areas, they can only be grown if supported by irrigation.

[6] The Buputja live in historical northern New South Wales west of the New England tablelands. The Yalatji live in the historical Darling Downs, among the headwaters of the eponymous river.

[7] Orthodox Pliri priests would be right alongside Machiavelli’s adage of never doing an enemy a small injury, although he would not necessarily have agreed with their idea of fighting wars without taking prisoners.

* * *

Thoughts?

P.S. From here, there are two more posts coming up about the culture of *Australia in 1618. One post will be on Tjibarr, the kingdom along the *Murray, although that post may be long enough to be split into two. The other post will be on the Daluming kingdom, on the east coast. After that, I’ll be moving on to posts about European contact with *Australia (initially the Dutch). At some point, I’ll also give an overview of the Maori in *New Zealand, but it’s taking a while to work out the details of that culture, so I’ll move on to showing European contact first.

I do like the different religion - it does remind me of Taoism or Islam - although more of a philosophy than anything else. You've put a lot of detail into "Good Man"'s thought and it reflects it. I'm guessing that much of this faith is in the interior rather than the coastal parts of this alternate Australia.

By the way - in the flag section, what does the "mind" flag represents since the top one obviously states the tribe/section of the army unit/an individual Emperor?

By the way - in the flag section, what does the "mind" flag represents since the top one obviously states the tribe/section of the army unit/an individual Emperor?