You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Asami

Banned

一. 明治大帝

Chapter One: Meiji the Great

“…the contrast between that which preceded the funeral car and that which followed it was striking indeed. Before it went old Japan; after it came new Japan.”

- New York Times, 1912, after the funeral of the Meiji Emperor

The death of the Emperor Meiji was perhaps the most somber event to have taken Japan in years. The Emperor had watched over the ascent of Japan through the 19th century recursive bakufu governance, and into the modern age of constitutional government, where the storms of war were gathering as Europe armed itself to the hilt, and China fell into a state of anarchy under the guise of republican revolution, lead by men like Yuan Shikai, Sun Yat-sen, and the Kuomintang.

At approximately 1 o’clock in the morning of the same day as the Emperor’s death (30 July 1912), two of the three 'sanshu no jingi' were handed over to the Crown Prince. He received Kusanagi, the sword; and Yasakani no Magatama, the jewel, as well as the formal seal of the state. The new Emperor was not of completely sound mind and body, having spent his entire life with varying levels of neurological issues; however, he still found himself in possession of the items that struck like a bolt from the blue—he was now the Emperor of Japan, and in his hands, he possessed the items that legitimized his rule. He was conferred these honors less than a quarter-hour after the demise of his father. With this done, the Meiji Era had ended, and the Taisho Era had begun.

Two weeks after the death of the Emperor, his body was transferred from his deathbed to the hinkyuu (殯宮, temporary imperial mortuary) which had been put together in the central pavilion of the Imperial Palace. The Emperor’s deceased body had been enclosed in a space boxed in on three sides with white cloths, and the fourth by a shutter. He was placed in this enclosure with his sword, and his coffin decorated with the sakaki (榊), a sacred tree in Shinto. During the procession of his body lying in state, over 50 days, every tenth day, offerings of food and textiles were placed before the coffin, and eulogies to honor the Emperor were given.

On the 29th, the Emperor, whom in his life as Crown Prince had the name Mutsuhito, and as Emperor was merely referred to as ‘His Majesty the Emperor’ (天皇陛下, tennouheika), was given his permanent posthumous name. It was decided that the posthumous Emperor should be known forever more as 明治天皇 (Meiji-tennou). The Crown Prince also decided upon his nengou (era) name. He would take up 大正 (Taishou), which loosely translates to 'great righteousness’.

On the 4th of September, the diplomatic corps of foreign nations were invited to pay a visit to the Emperor’s place of temporary internment and pay their respects. As the de-facto leader of the diplomatic corps in Japan, the Ambassador to Japan from the Court of St. James deposited a silver crown at the Emperor’s grave.

9 days later, a memorial tablet carrying the name of Emperor Meiji was placed in his private chambers, while the funeral was conducted. At 19:00, the body was carried via a golden chariot from the palace towards his eternal resting place. He was accompanied by a funeral parade of 300 people carrying torches, gongs, drums and other material. This procession was also joined by military bands, and a youth group from Yase, northeast of the ancient capital, Kyoto.

At 11:15, the Emperor’s last rites, salutes and offerings were started. General Nogi, a hero of the Russo-Japanese War, and a man of great national renown, committed seppuku with his wife so that he may accompany the Emperor in the afterlife. Whilst the funeral celebrations and other things like it would not stop until 1913, the newly ascended and not-entirely-present Emperor Taishou would have to buckle down and prepare himself for his new role as Emperor of Japan.

It was not long after the last rites were given, that a new political crisis sprang up, testing the new Emperor’s mettle and wit.

- New York Times, 1912, after the funeral of the Meiji Emperor

The death of the Emperor Meiji was perhaps the most somber event to have taken Japan in years. The Emperor had watched over the ascent of Japan through the 19th century recursive bakufu governance, and into the modern age of constitutional government, where the storms of war were gathering as Europe armed itself to the hilt, and China fell into a state of anarchy under the guise of republican revolution, lead by men like Yuan Shikai, Sun Yat-sen, and the Kuomintang.

At approximately 1 o’clock in the morning of the same day as the Emperor’s death (30 July 1912), two of the three 'sanshu no jingi' were handed over to the Crown Prince. He received Kusanagi, the sword; and Yasakani no Magatama, the jewel, as well as the formal seal of the state. The new Emperor was not of completely sound mind and body, having spent his entire life with varying levels of neurological issues; however, he still found himself in possession of the items that struck like a bolt from the blue—he was now the Emperor of Japan, and in his hands, he possessed the items that legitimized his rule. He was conferred these honors less than a quarter-hour after the demise of his father. With this done, the Meiji Era had ended, and the Taisho Era had begun.

Two weeks after the death of the Emperor, his body was transferred from his deathbed to the hinkyuu (殯宮, temporary imperial mortuary) which had been put together in the central pavilion of the Imperial Palace. The Emperor’s deceased body had been enclosed in a space boxed in on three sides with white cloths, and the fourth by a shutter. He was placed in this enclosure with his sword, and his coffin decorated with the sakaki (榊), a sacred tree in Shinto. During the procession of his body lying in state, over 50 days, every tenth day, offerings of food and textiles were placed before the coffin, and eulogies to honor the Emperor were given.

On the 29th, the Emperor, whom in his life as Crown Prince had the name Mutsuhito, and as Emperor was merely referred to as ‘His Majesty the Emperor’ (天皇陛下, tennouheika), was given his permanent posthumous name. It was decided that the posthumous Emperor should be known forever more as 明治天皇 (Meiji-tennou). The Crown Prince also decided upon his nengou (era) name. He would take up 大正 (Taishou), which loosely translates to 'great righteousness’.

On the 4th of September, the diplomatic corps of foreign nations were invited to pay a visit to the Emperor’s place of temporary internment and pay their respects. As the de-facto leader of the diplomatic corps in Japan, the Ambassador to Japan from the Court of St. James deposited a silver crown at the Emperor’s grave.

9 days later, a memorial tablet carrying the name of Emperor Meiji was placed in his private chambers, while the funeral was conducted. At 19:00, the body was carried via a golden chariot from the palace towards his eternal resting place. He was accompanied by a funeral parade of 300 people carrying torches, gongs, drums and other material. This procession was also joined by military bands, and a youth group from Yase, northeast of the ancient capital, Kyoto.

At 11:15, the Emperor’s last rites, salutes and offerings were started. General Nogi, a hero of the Russo-Japanese War, and a man of great national renown, committed seppuku with his wife so that he may accompany the Emperor in the afterlife. Whilst the funeral celebrations and other things like it would not stop until 1913, the newly ascended and not-entirely-present Emperor Taishou would have to buckle down and prepare himself for his new role as Emperor of Japan.

It was not long after the last rites were given, that a new political crisis sprang up, testing the new Emperor’s mettle and wit.

Last edited:

Asami

Banned

二. 大正政変

Chapter Two: Taishou Political Crisis

November 1912 - June 1914

By the end of the year, the Emperor’s first trials would be undertaken. Under the Meiji Emperor, government spending had grown incredibly high, as the Imperial Japanese Army sought to expand. The Meiji Constitution provided a clause in which the military would come to have a level of bargaining power over the civilian government—the constitution required that the office of Army Minister must be filled by an active-service Lieutenant General or General.

In the months following the Emperor’s death, debates and disputes over the military budget for 1913 had continued to escalate. Prime Minister Saionji Kinmochi did not want to further empower the armed forces, whilst the armed forces, largely under the leadership of genrō Field Marshal Yamagata Aritomo, wanted to further expand the budget for the Army to field stronger units to further their expansionist thirst, which had been only briefly satiated with the annexation of Korea in 1910, and the victories over Russia and China in 1905 and 1894, respectively.

In November 1912, General Uehara, the sitting Army Minister, resigned due to the inability for the cabinet to accede to the Army’s demands. Despite the attempts of the Prime Minister, no military officer was willing to take the position out of fear of being ostracized from their own military comrades.

On December 21st, 1912, Prime Minister Saionji was forced to resign, bringing down his civilian government.

The Emperor was initially pressured to appoint Katsura Tarou to the office of Prime Minister. Katsura was a former military officer, and a member of the genrō. However, the Emperor exercised a more neutral option. Inoue Kaoru was appointed to the office of Prime Minister on the same day. Inoue was meant primarily to be a stop-gap measure, and would keep the state on a balanced line between the Army and Navy’s propelling influence.

Almost immediately, the Army and Navy threatened to undermine the Inoue government by refusing to allow the appointment of military ministers within the government. They insisted that the Emperor appointed a man from their two quarreling factions to the office, and spare them the theatrics of a statesman. The Emperor was not very happy with this assertion on their part, and issued an edict, mandating that the Navy and Army were both required to provide to the cabinet appointments to the ministry.

To gather support for him democratically, the Prime Minister managed to cultivate many representatives in the Diet away from the main parties, and called together the formation of the 自由党 (Jiyuuto, ‘Freedom Party’).

While the Jiyuuto was not the majority party in the Diet, it was a marked step in the establishment of a continuity of constitutional politics and the marked attempts by anti-militarists to keep the military from meddling in civilian government affairs. The legislative system of the Taisho era is pointedly remembered as being overly chaotic, with new parties springing up constantly in the name of certain policy or personal advocating. The Jiyuuto was the first party which billed itself as a ‘big-tent party’, encompassing the support for certain freedoms for male populations, and for the state to lend its aid to the developing zaibatsu to expand Japan’s economic power instead of outright subjugating everyone. The party borrowed its name from an early Meiji era political party, the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement (自由民権運動), which sought to establish universal democracy instead of oligarchic democracy. The Jiyuuto was soon joined by other small parties in forming an informal alliance, called the Sakurakai (‘cherry blossom society’) which was dedicated to the empowerment of the civilian government, and the continuation of the balance of Imperial power, and civilian power.

While the public did stage protests aimed against the entrenchment of the genrō over the general authority of the democratic civilian government with his appointment, the Prime Minister managed to silence many of the protests by openly challenging the ‘military appointments’ rule that had undone the previous administration.

He convinced the increasingly annoyed Diet to repeal the rule that required both a Navy Minister and an Army Minister be appointed to the office. The repeal of the rule took place in late January 1913.

With his best efforts put into place, the Prime Minister managed to stave off attempts to unseat him from within and outside of the Diet, and secured his continuous rule, whilst the Emperor dealt with his increasingly infirm mind and body.

In early 1914, Prime Minister Inoue publicized and was the primary force behind what would become the Siemens Scandal. This scandal revealed that the Japanese navy, which was under a rapid expansion program to meet the demands of a potential war in the Pacific, and the need to assert Japanese dominance in the region—was importing necessary materials, such as advanced plans and weaponry. While this was not bad by itself, the details were what mattered—to meet their needs, they were importing from Europe.

Siemens AG, a German company, was enjoying a monopoly over Japanese contracts in exchange for a 15% kickback to the naval authorities responsible for the contracts.

After an attempt by the British company Vickers to take the contracts by offering a 25% kickback and a significant sum of money to the Japanese admiral responsible for anointing them as the primary provider of warship materials, the German headquarters of Siemens fired off a telegram to Tokyo, demanding clarification into matter.

Despite the efforts of Siemens to downplay the situation to their corporate masters, Karl Richter, an employee of Siemens, stole incriminating documents, and through the chain of money passing through the palms of politicians and men, they ended up in the hands of the Prime Minister.

The Prime Minister’s public reveal of the information whipped Japan, and its press corps into a frenzy, particularly when it was revealed that the Navy was going to attempt to force the Cabinet and Diet to approve a tax increase to pay for the rampantly over-budget Navy. By mid-February, most of the naval officers involved in the matter were arrested, and the government had been cleared of being involved with the charges, as the Prime Minister had no prior ties to the Navy.

Dozens of people were arrested in the matter of the procurement scandal, and in March, the Diet passed a heavily amended Naval Budget for 1914, significantly reducing the money that the Navy had to expand their scope. A court martial reduced several men, including Saitou Makoto and one of the genrō, Admiral Yamamoto Gonnohyoe, to a lower rank, although both men avoided imprisonment. As well, the Japanese government banned Vickers and Siemens from further contracts for the Japanese navy.

Once all was said and done, the Prime Minister was resolute to continue the ship of state forward. However, a few weeks after the affair had concluded, and the men were behind bars or discredited, the world was turned upside down…

In the months following the Emperor’s death, debates and disputes over the military budget for 1913 had continued to escalate. Prime Minister Saionji Kinmochi did not want to further empower the armed forces, whilst the armed forces, largely under the leadership of genrō Field Marshal Yamagata Aritomo, wanted to further expand the budget for the Army to field stronger units to further their expansionist thirst, which had been only briefly satiated with the annexation of Korea in 1910, and the victories over Russia and China in 1905 and 1894, respectively.

In November 1912, General Uehara, the sitting Army Minister, resigned due to the inability for the cabinet to accede to the Army’s demands. Despite the attempts of the Prime Minister, no military officer was willing to take the position out of fear of being ostracized from their own military comrades.

On December 21st, 1912, Prime Minister Saionji was forced to resign, bringing down his civilian government.

The Emperor was initially pressured to appoint Katsura Tarou to the office of Prime Minister. Katsura was a former military officer, and a member of the genrō. However, the Emperor exercised a more neutral option. Inoue Kaoru was appointed to the office of Prime Minister on the same day. Inoue was meant primarily to be a stop-gap measure, and would keep the state on a balanced line between the Army and Navy’s propelling influence.

Almost immediately, the Army and Navy threatened to undermine the Inoue government by refusing to allow the appointment of military ministers within the government. They insisted that the Emperor appointed a man from their two quarreling factions to the office, and spare them the theatrics of a statesman. The Emperor was not very happy with this assertion on their part, and issued an edict, mandating that the Navy and Army were both required to provide to the cabinet appointments to the ministry.

To gather support for him democratically, the Prime Minister managed to cultivate many representatives in the Diet away from the main parties, and called together the formation of the 自由党 (Jiyuuto, ‘Freedom Party’).

While the Jiyuuto was not the majority party in the Diet, it was a marked step in the establishment of a continuity of constitutional politics and the marked attempts by anti-militarists to keep the military from meddling in civilian government affairs. The legislative system of the Taisho era is pointedly remembered as being overly chaotic, with new parties springing up constantly in the name of certain policy or personal advocating. The Jiyuuto was the first party which billed itself as a ‘big-tent party’, encompassing the support for certain freedoms for male populations, and for the state to lend its aid to the developing zaibatsu to expand Japan’s economic power instead of outright subjugating everyone. The party borrowed its name from an early Meiji era political party, the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement (自由民権運動), which sought to establish universal democracy instead of oligarchic democracy. The Jiyuuto was soon joined by other small parties in forming an informal alliance, called the Sakurakai (‘cherry blossom society’) which was dedicated to the empowerment of the civilian government, and the continuation of the balance of Imperial power, and civilian power.

While the public did stage protests aimed against the entrenchment of the genrō over the general authority of the democratic civilian government with his appointment, the Prime Minister managed to silence many of the protests by openly challenging the ‘military appointments’ rule that had undone the previous administration.

He convinced the increasingly annoyed Diet to repeal the rule that required both a Navy Minister and an Army Minister be appointed to the office. The repeal of the rule took place in late January 1913.

With his best efforts put into place, the Prime Minister managed to stave off attempts to unseat him from within and outside of the Diet, and secured his continuous rule, whilst the Emperor dealt with his increasingly infirm mind and body.

In early 1914, Prime Minister Inoue publicized and was the primary force behind what would become the Siemens Scandal. This scandal revealed that the Japanese navy, which was under a rapid expansion program to meet the demands of a potential war in the Pacific, and the need to assert Japanese dominance in the region—was importing necessary materials, such as advanced plans and weaponry. While this was not bad by itself, the details were what mattered—to meet their needs, they were importing from Europe.

Siemens AG, a German company, was enjoying a monopoly over Japanese contracts in exchange for a 15% kickback to the naval authorities responsible for the contracts.

After an attempt by the British company Vickers to take the contracts by offering a 25% kickback and a significant sum of money to the Japanese admiral responsible for anointing them as the primary provider of warship materials, the German headquarters of Siemens fired off a telegram to Tokyo, demanding clarification into matter.

Despite the efforts of Siemens to downplay the situation to their corporate masters, Karl Richter, an employee of Siemens, stole incriminating documents, and through the chain of money passing through the palms of politicians and men, they ended up in the hands of the Prime Minister.

The Prime Minister’s public reveal of the information whipped Japan, and its press corps into a frenzy, particularly when it was revealed that the Navy was going to attempt to force the Cabinet and Diet to approve a tax increase to pay for the rampantly over-budget Navy. By mid-February, most of the naval officers involved in the matter were arrested, and the government had been cleared of being involved with the charges, as the Prime Minister had no prior ties to the Navy.

Dozens of people were arrested in the matter of the procurement scandal, and in March, the Diet passed a heavily amended Naval Budget for 1914, significantly reducing the money that the Navy had to expand their scope. A court martial reduced several men, including Saitou Makoto and one of the genrō, Admiral Yamamoto Gonnohyoe, to a lower rank, although both men avoided imprisonment. As well, the Japanese government banned Vickers and Siemens from further contracts for the Japanese navy.

Once all was said and done, the Prime Minister was resolute to continue the ship of state forward. However, a few weeks after the affair had concluded, and the men were behind bars or discredited, the world was turned upside down…

Last edited:

Asami

Banned

三. 第一次世界大戦

Chapter Three: World War I

June 1914—January 1915

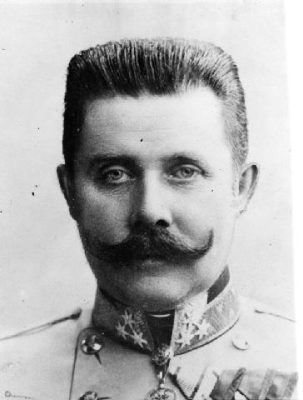

On June 28th, 1914, the world was forever changed. Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, was assassinated in Sarajevo during a visit to the newly annexed Bosnian territory. At 10:45 am, Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg were shot dead by a Serbian nationalist named Gavrilo Princip.

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand sent waves rocking through the courts of Europe. Anti-Serb riots rocked the city of Sarajevo, in which Croatian and Bosniak people killed ethnic Serbs and destroyed Serbian businesses explicitly to destroy Serbian influence in the province that Vienna had annexed a scant 6 years prior.

After a month of attempts to reach a diplomatic solution—during which time, all efforts had been solidly rebuffed by Serbia and their patron, the Russian Empire, the Austrians turned to coercion to get what they wanted. On 23rd July, the Austrians issued the July Ultimatum, a list of ten demands which were made intentionally unacceptable as so to provoke a war against the Serbian monarchy. The following day, the Russian Tsar, Nicholas II, ordered a general mobilization of the armed forces for two Ukrainian districts, the Kazan district, and the Moscow districts—as well as his navies in the Baltic and Black Sea.

The day after that, July 25th, the Serbs mobilized their armed forces and announced the accepting of 9 of the ten terms of the ultimatum—all except for Article Six, which would have mandated that the Austrians be able to send delegates to personally investigate Serbian participation in assassination of Franz Ferdinand.

After breaking off relations and mobilizing, on July 28th, 1914, the Austro-Hungarian Empire declared war on the Kingdom of Serbia, plunging the world into a war that would take millions of lives before it’s end. The following day, Russia issued mobilization orders against Austria-Hungary, drawing the ire of Germany—whom then demanded Russia stop. On the 30th, Russia then mobilized against Germany. Kaiser Wilhelm II, in an impassioned plea to his cousin Nicholas II, requested he suspend mobilization, an offer which was refused.

On August 1st, 1914, Germany declared war on Russia, which had mobilized against the Austro-Hungarian state already. The first stage of the Great War had taken shape, and the two soon went to blows. However, there was another stage that needed mentioning—the West.

France and Germany were historical enemies, and the two loathed each other so immensely, over the matters of Alsace-Lorraine, and Germany’s brutal defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War years prior. In the following days, Germany declared war and attempted to invade Luxembourg and France. On August 4th, German forces crossed into Belgium after the Belgians refused to grant the Germans passage.

That same day, Britain declared war on the German Empire, as the Germans had violated the Treaty of London, and had refused British demands to keep Belgium neutral in the war.

Japan’s involvement in World War I largely stemmed from their 1902 alliance with the British Empire. In the first week of the war, the Japanese government decided that the situation afforded to them was too good—even Prime Minister Inoue recognized that by seizing Germany’s territories in China, it would allow for the expansion of Japanese economic power, and allow for Japan to wedge her way into a position of hegemony in Asia, without the need for careless warmongering, particularly against a nation like China, or, Kami forbid, America.

On 7 August, the British replied to Japan’s initial diplomatic suggestion, this time officially asking Japan to help eliminate raiders from the Imperial German Navy’s Ostasienflotte in and around Chinese waters. Japan agreed to this, and dispatched an ultimatum to Germany on 14 August 1914, demanding the immediate handover of all German territory in the Pacific to Japanese control. Berlin did not answer the ultimatum, believing it impossible for Japan to inflict any damage upon them in any manner. Thus, Germany and Japan went to war after the Japanese issued a declaration of war on August 23.

Two days later, Japan declared war on the Austrians after they refused to withdraw the SMS Kaiserin Elizabeth from the Tsingtao concession port.

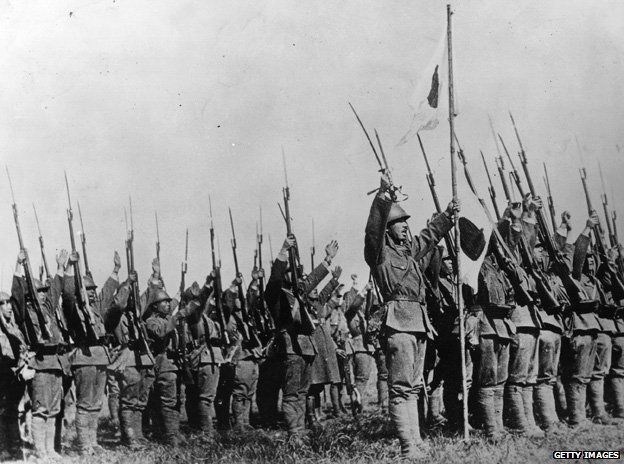

The Japanese wasted no time in sending troops to dispatch Germany’s colonies in Asia. In early September, Japanese naval forces landed in the Shandong Peninsula, which was only nominally under the control of the Peking government.

Yuan Shikai remained President of the Republic of China, but his power was rapidly collapsing. The man’s ham-fisted efforts to contain people whom disagreed with him was damaging him politically. By 1914, he was ruling with military fiat, banning organizations (including the revolutionary Kuomintang organization), and was disregarding the power of the provinces, preferring to rule entirely from Peking, and Peking alone. However, warlords, and Sun Yat-sen's revolutionary Kuomintang were throwing off his game, and giving him one headache after another.

So, when the Japanese staged their invasion of Qingdao from within Chinese territory, they received no complaints from the Chinese government, as they were completely and utterly subdued and incapable of issuing any type of response to the Japanese violation of their territory.

During the Japanese siege of Qingdao, on 6 September, a seaplane launched from the Wakamiya inflicted damage upon Kaiserin Elizabeth and the German gunboat Jaguar with bombs, but did not sink the ships. As the Japanese forced their way into the settlement, the Jaguar and her three sister ships were scuttled. The Kaiserin Elizabeth soon followed. While Japan did not capture any ships, they did manage to take Qingdao, which was upheld as a triumph back home.

Throughout October 1914, the Imperial Navy, looking to play a risky game and gain more influence domestically, acted without the support of the state, and seized several of Germany’s island colonies in the Pacific Basin on their own. This annoyed the Prime Minister, but he played it off, stating that the civilian leadership had determined these targets to be of use in the long-term, as it would allow Japan’s safety to be assured. He was unsure how to deal with the unruly naval commanders acting outside of the scope of their orders, but did not want to undermine the war effort.

The first months of World War I had afforded for the Empire of Japan an immense ability to expand her power. Prime Minister Inoue was very cautious about how to deal with these issues, and did not want to allow any branch of the armed forces to gain an upper-hand and impose their will on the civilian government. He hoped that more moderate officers would emerge, but he was doubtful this would take place.

In 1915, with the Germans incapable of launching a counter-attack against Japan's seizure of their colonies, Japan's foreign policy matters drew the Prime Minister's attention to China. Yuan Shikai was continuing to wreak havoc in the Chinese political hierarchy, and calls were growing for the Prime Minister and his government to do something to bring China into line. While some wanted to simply lay out an ultimatum to submit to Japanese authority, Prime Minister Inoue was more willing to play a longer game...

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand sent waves rocking through the courts of Europe. Anti-Serb riots rocked the city of Sarajevo, in which Croatian and Bosniak people killed ethnic Serbs and destroyed Serbian businesses explicitly to destroy Serbian influence in the province that Vienna had annexed a scant 6 years prior.

After a month of attempts to reach a diplomatic solution—during which time, all efforts had been solidly rebuffed by Serbia and their patron, the Russian Empire, the Austrians turned to coercion to get what they wanted. On 23rd July, the Austrians issued the July Ultimatum, a list of ten demands which were made intentionally unacceptable as so to provoke a war against the Serbian monarchy. The following day, the Russian Tsar, Nicholas II, ordered a general mobilization of the armed forces for two Ukrainian districts, the Kazan district, and the Moscow districts—as well as his navies in the Baltic and Black Sea.

The day after that, July 25th, the Serbs mobilized their armed forces and announced the accepting of 9 of the ten terms of the ultimatum—all except for Article Six, which would have mandated that the Austrians be able to send delegates to personally investigate Serbian participation in assassination of Franz Ferdinand.

After breaking off relations and mobilizing, on July 28th, 1914, the Austro-Hungarian Empire declared war on the Kingdom of Serbia, plunging the world into a war that would take millions of lives before it’s end. The following day, Russia issued mobilization orders against Austria-Hungary, drawing the ire of Germany—whom then demanded Russia stop. On the 30th, Russia then mobilized against Germany. Kaiser Wilhelm II, in an impassioned plea to his cousin Nicholas II, requested he suspend mobilization, an offer which was refused.

On August 1st, 1914, Germany declared war on Russia, which had mobilized against the Austro-Hungarian state already. The first stage of the Great War had taken shape, and the two soon went to blows. However, there was another stage that needed mentioning—the West.

France and Germany were historical enemies, and the two loathed each other so immensely, over the matters of Alsace-Lorraine, and Germany’s brutal defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War years prior. In the following days, Germany declared war and attempted to invade Luxembourg and France. On August 4th, German forces crossed into Belgium after the Belgians refused to grant the Germans passage.

That same day, Britain declared war on the German Empire, as the Germans had violated the Treaty of London, and had refused British demands to keep Belgium neutral in the war.

Japan’s involvement in World War I largely stemmed from their 1902 alliance with the British Empire. In the first week of the war, the Japanese government decided that the situation afforded to them was too good—even Prime Minister Inoue recognized that by seizing Germany’s territories in China, it would allow for the expansion of Japanese economic power, and allow for Japan to wedge her way into a position of hegemony in Asia, without the need for careless warmongering, particularly against a nation like China, or, Kami forbid, America.

On 7 August, the British replied to Japan’s initial diplomatic suggestion, this time officially asking Japan to help eliminate raiders from the Imperial German Navy’s Ostasienflotte in and around Chinese waters. Japan agreed to this, and dispatched an ultimatum to Germany on 14 August 1914, demanding the immediate handover of all German territory in the Pacific to Japanese control. Berlin did not answer the ultimatum, believing it impossible for Japan to inflict any damage upon them in any manner. Thus, Germany and Japan went to war after the Japanese issued a declaration of war on August 23.

Two days later, Japan declared war on the Austrians after they refused to withdraw the SMS Kaiserin Elizabeth from the Tsingtao concession port.

The Japanese wasted no time in sending troops to dispatch Germany’s colonies in Asia. In early September, Japanese naval forces landed in the Shandong Peninsula, which was only nominally under the control of the Peking government.

Yuan Shikai remained President of the Republic of China, but his power was rapidly collapsing. The man’s ham-fisted efforts to contain people whom disagreed with him was damaging him politically. By 1914, he was ruling with military fiat, banning organizations (including the revolutionary Kuomintang organization), and was disregarding the power of the provinces, preferring to rule entirely from Peking, and Peking alone. However, warlords, and Sun Yat-sen's revolutionary Kuomintang were throwing off his game, and giving him one headache after another.

So, when the Japanese staged their invasion of Qingdao from within Chinese territory, they received no complaints from the Chinese government, as they were completely and utterly subdued and incapable of issuing any type of response to the Japanese violation of their territory.

During the Japanese siege of Qingdao, on 6 September, a seaplane launched from the Wakamiya inflicted damage upon Kaiserin Elizabeth and the German gunboat Jaguar with bombs, but did not sink the ships. As the Japanese forced their way into the settlement, the Jaguar and her three sister ships were scuttled. The Kaiserin Elizabeth soon followed. While Japan did not capture any ships, they did manage to take Qingdao, which was upheld as a triumph back home.

Throughout October 1914, the Imperial Navy, looking to play a risky game and gain more influence domestically, acted without the support of the state, and seized several of Germany’s island colonies in the Pacific Basin on their own. This annoyed the Prime Minister, but he played it off, stating that the civilian leadership had determined these targets to be of use in the long-term, as it would allow Japan’s safety to be assured. He was unsure how to deal with the unruly naval commanders acting outside of the scope of their orders, but did not want to undermine the war effort.

The first months of World War I had afforded for the Empire of Japan an immense ability to expand her power. Prime Minister Inoue was very cautious about how to deal with these issues, and did not want to allow any branch of the armed forces to gain an upper-hand and impose their will on the civilian government. He hoped that more moderate officers would emerge, but he was doubtful this would take place.

In 1915, with the Germans incapable of launching a counter-attack against Japan's seizure of their colonies, Japan's foreign policy matters drew the Prime Minister's attention to China. Yuan Shikai was continuing to wreak havoc in the Chinese political hierarchy, and calls were growing for the Prime Minister and his government to do something to bring China into line. While some wanted to simply lay out an ultimatum to submit to Japanese authority, Prime Minister Inoue was more willing to play a longer game...

Last edited:

Asami

Banned

四. 反共和党運動

Chapter 4: The Anti-Republican Movement

January 1915—September 1915

In 1908, the Dowager Empress Cixi of China died, leaving the throne to the nearly 3-year-old Aisin-Gioro Pu-yi. The new Emperor was placed under a regency lead by his father, Prince Chun. After a brief four years as Emperor, in 1912, the Xinhai Revolution brought down the Qing Empire, and dissolved it. The absolute power of the Forbidden City began to poison the young prince’s mind, and he soon became a tyrant, ordering the beating of eunuchs for minor transgressions—however, the young Prince was also not without influence, namely in the form of tutors from foreign countries, and a few sensible minds in the court.

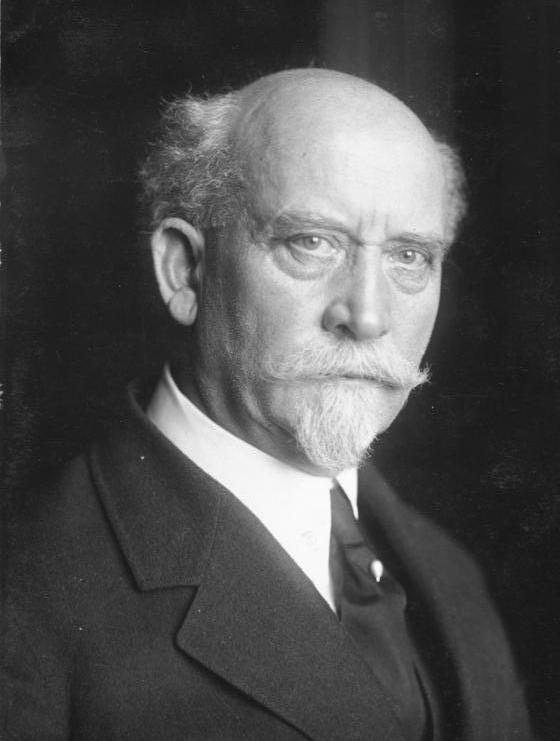

Prime Minister Inoue recognized that a divided China, even if not entirely under Japanese authority, was still a better solution than a single, unified, indivisible China. He acquiesced to some of the radicals’ demands, and issued what were then termed as the 対華15ヶ条要求 (en: Fifteen Demands). These demands were nothing Japan had not already demanded of China, but it was a general reaffirmation of Japan’s position as the dominant regional power in China. Yuan Shikai’s government attempted to force Japan to withdraw the demands by publicizing them, sparking a wave of anti-Japanese sentiment in China.

However, in the Fifteen Demands, while Japan demanded a laundry list of things—including preferential treatment, and the ceasing of handing out concession ports to foreign powers, it also demanded a significant number of extensions of Open Door policies that had been in place prior, despite extension of Japanese economic dominance in Manchuria and Shandong. The Fifteen Demands, therefore, received zero complaint from amongst the foreign courts, particularly Britain and America, whom stood to gain from the extension of the Open-Door policy. Russia’s complaints were heard but not listened to—as they were in the middle of fighting a war of horrendous attrition against Germany.

Yuan’s plan backfired, and the President accepted Japan’s demands. Japan’s exports to China took a minor hit, but did not sharply drop, as the attempts by revolutionaries to organize a boycott of Japanese goods failed, as the terms of the treaty were not more than what the Chinese had already been expecting.

With that done, Prime Minister Inoue began to plot to damage the integrity of the Chinese Republic through diplomatic intrigue. With Yuan’s power teetering, Inoue made overtures to the Forbidden City’s rump court, implying Japan’s interest in the restoration of the Qing monarchy under certain… constitutional reforms on the Qing’s part. This drew the attention of some royalists within both Yuan’s government, and the Beiyang Army, whom were interested at the idea of restoring the defunct monarchy.

In secrecy, the Anti-Republican Movement was put together, mostly lead by a cabal of Chinese officers, the Qing monarchy’s rump leadership, and several Japanese advisers whom had an express interest in utilizing a dependency in China to rapidly pump money into the economy. This movement began to consider operations to weaken the power of the Republic, and to set the stage for a restoration, at least in parts of China—they were in it for the long-haul, as the Japanese advisers put it.

The treatise that put the Fifteen Demands into place was finally signed in May 1915, and Yuan could turn internally to start putting into place his plan to end the strife in China—whatever that was.

Inoue’s government then turned their attentions to the interior of Japan, particularly Korea. Korea had been annexed by Japan five years prior with the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty of 1910. Since then, Terauchi Masatake had been running the peninsula as Governor-General. His policy methods of controlling Korea centered entirely on one goal—assimilation of Korea into Japan, and the eventual demise of Korean culture.

While Inoue and his Cabinet were not die-hard fans of Korea, or of Korean culture, they still understood that the continued militant oppression of Korea would end with something just like the Satsuma Rebellion that he had helped start, in which, unless Japan used military force to quell and kill dissenters, would spiral out of control until Korea was all but independent.

Inoue had to admit, however, that sometimes, Terauchi’s policies had unintended negative effects, but good intentions. Land reform was one of them—the policy had created bitterness and a spike of land efficiency. To make matters worse, Inoue had come to see that the position of Governor-General of Korea was little more than an extension of the Imperial Japanese Army’s attempts to weasel significant power away from the civilian government.

To this end, Inoue looked to figure out what steps could be taken to establish civilian control of the Governor-General’s office, and to prevent the overwhelming militarization of Korea from becoming a reality, more so than just a thought.

In June 1915, the Diet saw the proposal of the Power Reform Act of 1915, an act which would significantly weaken the powers of the Governors-General of Taiwan and Korea—a start which would ‘carry policy’ to other Japanese acquisitions across Asia. The Prime Minister utilized most of his political capital to carry this bill to its completion, claiming that unless the Japanese nation reformed their control of their possessions, they would never be able to instill harmony and peace there—as well, the political power of the Navy and Army was troubling, and this would be a ‘great step towards entrenching constitutional governance of our exterior territories’.

The bill managed to pass through the efforts of the Sakurakai and other ‘pro-Constitution’ politicians and bureaucrats. The armed forces were incredibly displeased, and many nationalists within the system were beginning to set into effect their own methods of dealing with this annoyance that was an anti-military Prime Minister.

With the bill passed, the Prime Minister set into action with appointing new Governors-General. For Taiwan, he was convinced by his Cabinet to appoint Den Kenjirou, a baron of the House of Peers, to the office. Den was a known member of the more conservative levels of society, but still voiced his support for reforms to assimilate Taiwan peacefully, and without the extensive measures of coercion.

In Korea, the process was a little less cut and dry. The Prime Minister, with Imperial assent, relieved Count Terauchi from his post. Terauchi returned to Japan and began to stir up sentiments against the government, claiming that the Prime Minister was playing favorites with Japan’s subjects than with Japan’s citizens, and began to coordinate nationalist sentiments and fervor against the Prime Minister.

In August, the office of Governor-General of Korea was filled, this time by Takahashi Korekiyo, the man whom had introduced a patent system in Japan, and had secured foreign loans during the Russo-Japanese War. The Prime Minister felt that if any man could strengthen Korea’s economic value to the Empire, it would be Takahashi.

Takahashi pledged to reform Korea and bring it up to par with the Empire proper, and proclaimed that by 1920, Korea would have more schools, more trains, and more industry. A side effect of this, was also the quiet ‘moderation’ of education in Korea, as his administration focused less on the forced assimilation of Korea, and more on the ‘assimilation by prosperity’ method that was being used in Taiwan. Korean language and cultural assets were no longer suppressed, and were taught alongside Japanese, with emphasis being placed on the cultural similarity, and fraternity of the Japanese and Korean peoples.

While Korean nationalism had not been stopped by this, Takahashi marked the first steps by a Japanese civilian government to attempt a reconciliation between subject and master, something that some Koreans of academic standing hoped would continue in the future.

With these efforts secured, the nation was struck with shock as Prime Minister Inoue died in September 1915. His appointed replacement was a member of the Sakurakai, this man was Minobe Tatsukichi, a 42-year-old constitutional scholar, whom was immensely unpopular in nationalist and military circles for his assertions that the state needed to take steps to prevent a ‘dual-government’ situation from emerging and the armed forces from dominating the government of Japan.

With Minobe’s empowerment as Prime Minister, the nationalists now felt it was time to act, before it was too late…

Prime Minister Inoue recognized that a divided China, even if not entirely under Japanese authority, was still a better solution than a single, unified, indivisible China. He acquiesced to some of the radicals’ demands, and issued what were then termed as the 対華15ヶ条要求 (en: Fifteen Demands). These demands were nothing Japan had not already demanded of China, but it was a general reaffirmation of Japan’s position as the dominant regional power in China. Yuan Shikai’s government attempted to force Japan to withdraw the demands by publicizing them, sparking a wave of anti-Japanese sentiment in China.

However, in the Fifteen Demands, while Japan demanded a laundry list of things—including preferential treatment, and the ceasing of handing out concession ports to foreign powers, it also demanded a significant number of extensions of Open Door policies that had been in place prior, despite extension of Japanese economic dominance in Manchuria and Shandong. The Fifteen Demands, therefore, received zero complaint from amongst the foreign courts, particularly Britain and America, whom stood to gain from the extension of the Open-Door policy. Russia’s complaints were heard but not listened to—as they were in the middle of fighting a war of horrendous attrition against Germany.

Yuan’s plan backfired, and the President accepted Japan’s demands. Japan’s exports to China took a minor hit, but did not sharply drop, as the attempts by revolutionaries to organize a boycott of Japanese goods failed, as the terms of the treaty were not more than what the Chinese had already been expecting.

With that done, Prime Minister Inoue began to plot to damage the integrity of the Chinese Republic through diplomatic intrigue. With Yuan’s power teetering, Inoue made overtures to the Forbidden City’s rump court, implying Japan’s interest in the restoration of the Qing monarchy under certain… constitutional reforms on the Qing’s part. This drew the attention of some royalists within both Yuan’s government, and the Beiyang Army, whom were interested at the idea of restoring the defunct monarchy.

In secrecy, the Anti-Republican Movement was put together, mostly lead by a cabal of Chinese officers, the Qing monarchy’s rump leadership, and several Japanese advisers whom had an express interest in utilizing a dependency in China to rapidly pump money into the economy. This movement began to consider operations to weaken the power of the Republic, and to set the stage for a restoration, at least in parts of China—they were in it for the long-haul, as the Japanese advisers put it.

The treatise that put the Fifteen Demands into place was finally signed in May 1915, and Yuan could turn internally to start putting into place his plan to end the strife in China—whatever that was.

Inoue’s government then turned their attentions to the interior of Japan, particularly Korea. Korea had been annexed by Japan five years prior with the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty of 1910. Since then, Terauchi Masatake had been running the peninsula as Governor-General. His policy methods of controlling Korea centered entirely on one goal—assimilation of Korea into Japan, and the eventual demise of Korean culture.

While Inoue and his Cabinet were not die-hard fans of Korea, or of Korean culture, they still understood that the continued militant oppression of Korea would end with something just like the Satsuma Rebellion that he had helped start, in which, unless Japan used military force to quell and kill dissenters, would spiral out of control until Korea was all but independent.

Inoue had to admit, however, that sometimes, Terauchi’s policies had unintended negative effects, but good intentions. Land reform was one of them—the policy had created bitterness and a spike of land efficiency. To make matters worse, Inoue had come to see that the position of Governor-General of Korea was little more than an extension of the Imperial Japanese Army’s attempts to weasel significant power away from the civilian government.

To this end, Inoue looked to figure out what steps could be taken to establish civilian control of the Governor-General’s office, and to prevent the overwhelming militarization of Korea from becoming a reality, more so than just a thought.

In June 1915, the Diet saw the proposal of the Power Reform Act of 1915, an act which would significantly weaken the powers of the Governors-General of Taiwan and Korea—a start which would ‘carry policy’ to other Japanese acquisitions across Asia. The Prime Minister utilized most of his political capital to carry this bill to its completion, claiming that unless the Japanese nation reformed their control of their possessions, they would never be able to instill harmony and peace there—as well, the political power of the Navy and Army was troubling, and this would be a ‘great step towards entrenching constitutional governance of our exterior territories’.

The bill managed to pass through the efforts of the Sakurakai and other ‘pro-Constitution’ politicians and bureaucrats. The armed forces were incredibly displeased, and many nationalists within the system were beginning to set into effect their own methods of dealing with this annoyance that was an anti-military Prime Minister.

With the bill passed, the Prime Minister set into action with appointing new Governors-General. For Taiwan, he was convinced by his Cabinet to appoint Den Kenjirou, a baron of the House of Peers, to the office. Den was a known member of the more conservative levels of society, but still voiced his support for reforms to assimilate Taiwan peacefully, and without the extensive measures of coercion.

In Korea, the process was a little less cut and dry. The Prime Minister, with Imperial assent, relieved Count Terauchi from his post. Terauchi returned to Japan and began to stir up sentiments against the government, claiming that the Prime Minister was playing favorites with Japan’s subjects than with Japan’s citizens, and began to coordinate nationalist sentiments and fervor against the Prime Minister.

In August, the office of Governor-General of Korea was filled, this time by Takahashi Korekiyo, the man whom had introduced a patent system in Japan, and had secured foreign loans during the Russo-Japanese War. The Prime Minister felt that if any man could strengthen Korea’s economic value to the Empire, it would be Takahashi.

Takahashi pledged to reform Korea and bring it up to par with the Empire proper, and proclaimed that by 1920, Korea would have more schools, more trains, and more industry. A side effect of this, was also the quiet ‘moderation’ of education in Korea, as his administration focused less on the forced assimilation of Korea, and more on the ‘assimilation by prosperity’ method that was being used in Taiwan. Korean language and cultural assets were no longer suppressed, and were taught alongside Japanese, with emphasis being placed on the cultural similarity, and fraternity of the Japanese and Korean peoples.

While Korean nationalism had not been stopped by this, Takahashi marked the first steps by a Japanese civilian government to attempt a reconciliation between subject and master, something that some Koreans of academic standing hoped would continue in the future.

With these efforts secured, the nation was struck with shock as Prime Minister Inoue died in September 1915. His appointed replacement was a member of the Sakurakai, this man was Minobe Tatsukichi, a 42-year-old constitutional scholar, whom was immensely unpopular in nationalist and military circles for his assertions that the state needed to take steps to prevent a ‘dual-government’ situation from emerging and the armed forces from dominating the government of Japan.

With Minobe’s empowerment as Prime Minister, the nationalists now felt it was time to act, before it was too late…

Last edited:

Asami

Banned

This is what the world looks like in September 1915.

The Central Powers are doing alright--Austria is beating Serbia, but is losing ground in Galicia-Lodomeria to the Russians. Germany is advancing in both theatres, and has cut off a large number of Belgian and French troops near Calais, but the French are fighting robust, and attempting to break the German salient. In Afro-Asia, the Ottomans have occupied Kuwait and have made advances in the Sinai, Iran and Russia. Germany's African colonies are almost all gone, as the Entente wreck havoc across the territory. France's lackluster African warfare has lead to Britain taking the lead in seizing German colonies, though Belgium is beginning an invasion of Tangikniya in order to get some of the spoils at the end of the war.

China is in an unstable state. The Kuomintang is active once more in the South, whilst the Japanese have expanded their influence in the Shandong region, and in Manchuria. Yuan's rule is as precarious as ever.

Germany has completely flopped in Asia, as Japan has occupied all their holdings, save New Guinea, which Australia rapidly occupied at the outbreak of war.

Asami

Banned

五. 十・六事件

Chapter Five: October 6 Incident

The morning of October 6, 1915 marked a significant evolution in the Japanese Empire’s politics, military, and national integrity. For months, the civilian government had been chipping away at the temporal power of the armed forces—through the reformation of how the Korean and Taiwanese Governor-Generals worked, and through the refusal to allow for the appointment of an active military officer to the office of Prime Minister—the new Prime Minister, Minobe Tatsukichi, was a known enemy of the Imperial war-machine’s influence.

The nationalists had been leading outbursts of violence in the months of the governance of Prime Minister Inoue and now, Prime Minister Minobe. With Minobe’s appointment, they felt ready to act. In the days before the October 6th incident, several high-ranking Japanese officers in the Army planned to focus on a few key items

First, the assassination of enemies of the Empire and those who stand in the way of kokutai. This meant that the Prime Minister, whom was a major proponent that the Emperor was an organ of the state, was the prime target.

Secondly, the reversion of all major reforms put into play since the ascent of the Taisho Emperor in 1912; this included the reforms to the Korean and Taiwanese colonies, which would be placed under direct military rule, as they were de facto before.

Thirdly, the dissolution of the Diet, and the full empowering of the Emperor as the sole embodiment of the state and the people. They felt that, should the Emperor not be willing to assume this role, they may be forced to replace the Emperor with a regency under one of his sons—his eldest, Prince Michi, seemed a viable candidate to replace the Emperor, but they also looked at Prince Chichibu as a potential replacement for the Emperor as well.

In the morning of October 6th, the plot went into action. The Army staged a coup d’etat in Taipei, Gyeongseong and in Tokyo. In Gyeongseong, they seized the Governor-General’s mansion—the Governor-General, fortunately, had been in the Northern Korean countryside at the time, and escaped death. Upon hearing of the seizure of power in Gyeongseong, Governor Takahashi did not return to Gyeongseong, but instead remained where he was with loyalist military forces.

In Taipei, the Governor-General managed to barely escape with his life. The small civilian boat he was on managed to slip through the early morning, and he arrived on Okinawa safe—the Army thereafter occupied the Governor-General’s office in Taipei as well. It was not long after that the office came under siege from loyalists.

In Tokyo, the largest concentration of Army traitors seized the Ministry of War, arresting scores of officers whom did not join their coup d’etat—they hoped to purge the Army of any dissenting officers, and convince the Navy to join them to force the Emperor to capitulate to their demands.

They attempted an encirclement of the Prime Minister’s house, but failed, as the Prime Minister had already fled after early news of the rebellion in Gyeongseong and Taipei had become clear. Overzealous members of the rebellion attempted to assault and force their way into the Imperial Palace to deliver their ultimatum to Emperor Taisho. However, upon entry, they were fired upon by several police-officers. One overzealous officer launched a small firebomb at the group of police officers and started a fire within the Imperial Palace. The quick spread of the fire eliminated the ability for the Emperor to reach safety. In the chaos, the Emperor attempted to affect his own escape from the burning Palace by climbing out of a second story window. However, the window-sill, still wet from a previous night’s rain, caused the Emperor to slip. The Emperor fell out of the window and fell on his head, knocking His Imperial Majesty out cold.

The rebellious soldiers were driven out of the Imperial grounds, and the Emperor was discovered shortly afterwards. News of what had happened to the Imperial Palace (now half-burned out) and the Emperor spread across Japan thanks to telegraph, and soon, members of the rebellious soldiers’ ranks were turning on themselves, and fighting soon broke out between those whom were reluctant accomplices, and those whom were die-hard militarists.

The turning point was when the rebels attempted to seize the Diet building and arrest those inside. Taking up weapons, many police officers, loyalist soldiers, and others, gathered at the Diet, and traded fire with the rebels from their barricades. Soon, more loyalist officers arrived and started attacking from the flank.

The Navy, which had been just as insulted by the civilian government’s actions, put down any attempts to join the rebellion. More moderate officers prevailed, and managed to prevent any major mutinies from erupting. More than 180 naval officers were arrested and handed over to the civilian government for trial.

The military coup d’etat failed after the Ministry of War was reclaimed by the Loyalists. The ring-leaders of the coup were arrested, tried, and sentenced to death in the same day. That same afternoon, Prime Minister Minobe ordered an investigation into both branches of the Armed Forces to verify that there were no more plotters and conspirators in their ranks.

Public trust in the armed forces was significantly damaged by their foolish venture that day, and hundreds of soldiers, officers and people with militarist and nationalist sentiment were arrested and imprisoned, or even executed. Yamamoto Gonnohyoue was named the ring-leader of the plot, and was executed on October 10th. The Emperor slipped into a coma induced by severe neurological trauma and pre-existing condition. With a regency needed, and none of his sons of age, someone new had to be found.

They enlisted the aid of Ōyama Iwao, an elder statesman and, ironically, one of the founders of the Imperial Japanese Army, to serve as Sesshou. While he was supportive of the genrō and against democratic politics, he was also very reserved, and did not put his interests before that of the state, and therefore pledged to serve as Regent and do his job with impartiality.

Whilst the Emperor’s children had not been involved in the coup, a great amount of public suspicion encircled both Michi and Chichibu, as they had been listed in the rebel’s demands as ‘replacements’ for the Emperor, should he have refused their demands.

While Michi would still inherit the Chrysanthemum Throne upon his father’s death, there was little to no enthusiasm for the Emperor to die any time soon.

The regency of Ōyama Iwao lasted a brief two months. On 2 December 1915, the Regent died of a heart attack. The council then convened, and anointed Hirata Tosuke as Sesshou, which is where he would stay until the Regency dissolved in 1919.

The nationalists had been leading outbursts of violence in the months of the governance of Prime Minister Inoue and now, Prime Minister Minobe. With Minobe’s appointment, they felt ready to act. In the days before the October 6th incident, several high-ranking Japanese officers in the Army planned to focus on a few key items

First, the assassination of enemies of the Empire and those who stand in the way of kokutai. This meant that the Prime Minister, whom was a major proponent that the Emperor was an organ of the state, was the prime target.

Secondly, the reversion of all major reforms put into play since the ascent of the Taisho Emperor in 1912; this included the reforms to the Korean and Taiwanese colonies, which would be placed under direct military rule, as they were de facto before.

Thirdly, the dissolution of the Diet, and the full empowering of the Emperor as the sole embodiment of the state and the people. They felt that, should the Emperor not be willing to assume this role, they may be forced to replace the Emperor with a regency under one of his sons—his eldest, Prince Michi, seemed a viable candidate to replace the Emperor, but they also looked at Prince Chichibu as a potential replacement for the Emperor as well.

In the morning of October 6th, the plot went into action. The Army staged a coup d’etat in Taipei, Gyeongseong and in Tokyo. In Gyeongseong, they seized the Governor-General’s mansion—the Governor-General, fortunately, had been in the Northern Korean countryside at the time, and escaped death. Upon hearing of the seizure of power in Gyeongseong, Governor Takahashi did not return to Gyeongseong, but instead remained where he was with loyalist military forces.

In Taipei, the Governor-General managed to barely escape with his life. The small civilian boat he was on managed to slip through the early morning, and he arrived on Okinawa safe—the Army thereafter occupied the Governor-General’s office in Taipei as well. It was not long after that the office came under siege from loyalists.

In Tokyo, the largest concentration of Army traitors seized the Ministry of War, arresting scores of officers whom did not join their coup d’etat—they hoped to purge the Army of any dissenting officers, and convince the Navy to join them to force the Emperor to capitulate to their demands.

They attempted an encirclement of the Prime Minister’s house, but failed, as the Prime Minister had already fled after early news of the rebellion in Gyeongseong and Taipei had become clear. Overzealous members of the rebellion attempted to assault and force their way into the Imperial Palace to deliver their ultimatum to Emperor Taisho. However, upon entry, they were fired upon by several police-officers. One overzealous officer launched a small firebomb at the group of police officers and started a fire within the Imperial Palace. The quick spread of the fire eliminated the ability for the Emperor to reach safety. In the chaos, the Emperor attempted to affect his own escape from the burning Palace by climbing out of a second story window. However, the window-sill, still wet from a previous night’s rain, caused the Emperor to slip. The Emperor fell out of the window and fell on his head, knocking His Imperial Majesty out cold.

The rebellious soldiers were driven out of the Imperial grounds, and the Emperor was discovered shortly afterwards. News of what had happened to the Imperial Palace (now half-burned out) and the Emperor spread across Japan thanks to telegraph, and soon, members of the rebellious soldiers’ ranks were turning on themselves, and fighting soon broke out between those whom were reluctant accomplices, and those whom were die-hard militarists.

The turning point was when the rebels attempted to seize the Diet building and arrest those inside. Taking up weapons, many police officers, loyalist soldiers, and others, gathered at the Diet, and traded fire with the rebels from their barricades. Soon, more loyalist officers arrived and started attacking from the flank.

The Navy, which had been just as insulted by the civilian government’s actions, put down any attempts to join the rebellion. More moderate officers prevailed, and managed to prevent any major mutinies from erupting. More than 180 naval officers were arrested and handed over to the civilian government for trial.

The military coup d’etat failed after the Ministry of War was reclaimed by the Loyalists. The ring-leaders of the coup were arrested, tried, and sentenced to death in the same day. That same afternoon, Prime Minister Minobe ordered an investigation into both branches of the Armed Forces to verify that there were no more plotters and conspirators in their ranks.

Public trust in the armed forces was significantly damaged by their foolish venture that day, and hundreds of soldiers, officers and people with militarist and nationalist sentiment were arrested and imprisoned, or even executed. Yamamoto Gonnohyoue was named the ring-leader of the plot, and was executed on October 10th. The Emperor slipped into a coma induced by severe neurological trauma and pre-existing condition. With a regency needed, and none of his sons of age, someone new had to be found.

They enlisted the aid of Ōyama Iwao, an elder statesman and, ironically, one of the founders of the Imperial Japanese Army, to serve as Sesshou. While he was supportive of the genrō and against democratic politics, he was also very reserved, and did not put his interests before that of the state, and therefore pledged to serve as Regent and do his job with impartiality.

Whilst the Emperor’s children had not been involved in the coup, a great amount of public suspicion encircled both Michi and Chichibu, as they had been listed in the rebel’s demands as ‘replacements’ for the Emperor, should he have refused their demands.

While Michi would still inherit the Chrysanthemum Throne upon his father’s death, there was little to no enthusiasm for the Emperor to die any time soon.

The regency of Ōyama Iwao lasted a brief two months. On 2 December 1915, the Regent died of a heart attack. The council then convened, and anointed Hirata Tosuke as Sesshou, which is where he would stay until the Regency dissolved in 1919.

Last edited:

Asami

Banned

六. 塹壕

Chapter Six: Entrenchment

The war in Europe was going nowhere fast.

By the start of 1916, the Western front was a grinding mess of unmovable trenches, with neither side managing to get the leg up on the other. While Germany had the natural upper-hand going into the year, her salient to the seat which had cut off supplies to Calais and Western Belgium had done very little to help the situation as the Kaiserliche Marine had not been able to prevent Britain from delivering supplies to the small pocket.

The Eastern Front was, in fact, very fluid. In September 1915, German forces were still slogging east through Congress Poland, however, by the time of the winter setting in a few scant months later, German forces had made it as far as Riga and Minsk, and settled in for Mother Winter’s steely bitterness.

For Austria, their fortunes against all their adversaries had been less than successful in the grand scheme of things—while Serbia had fallen in fall 1915, Italy had entered the war on the side of the Entente, and was causing issues for the Austrians. As well, they had failed to capture back most of their land from Russia, causing for Germany to ‘de-facto’ occupy chunks of Galicia-Lodomeria.

Bulgaria, which had joined the Central Powers in 1915, had been given a lion’s share of Southern Serbia for their contributions. However, the final ersatz ally of the Central Powers, the once glorious Ottoman Empire was suffering an unbelievable number of set-backs in their efforts to conquer Britain’s territories in Africa and Arabia. The British had reversed the Ottoman invasions of Egypt and Kuwait, and had made great strides in beating back the Turks—by the start of 1916, the British were in the Levant, Hejaz and Iraq causing significant issues for the Turks.

The Russians, despite their numerous defeats by the Central Powers, had managed to turn things around in the Caucasian Mountains, where they drove the Turks back across their own border, and had advanced into Trebizond, south to Lake Van. Their advancements into Turkish territory would be reversed by January 1917, and the border would go back to being static.

The Lusitania, an American cargo ship, was sank by the German Navy in 1915, sparking outrage amongst Americans whom felt that their rights as a nation were violated. Within weeks of that, false allegations of British diplomats attempting to bribe U.S. government officials enflamed anti-British sentiment in the United States as well—Irish-Americans, German-Americans and Jewish-Americans all patently disliked the British Empire. The Irish-Americans were largely expatriates whose families had been forced out of Ireland during the Potato Famine 70 years prior; the German-Americans and Jewish-Americans either had great ties back to Germany, or felt that Britain did not sufficiently represent their interests as groups.

Theodore Roosevelt, former President, and major political operative, gave a speech in 1916 crucifying these groups for ‘anti-American behaviour’, lambasting ‘hyphenated Americans’, claiming that the U.S. had no use for such people. While the patriotic sentiment was there, it just enflamed anti-Anglo sentiments, as many people felt that Teddy Roosevelt was implying that Anglos were the only acceptable form of Americans. Despite attempts by the governments of states and the federal government itself, the anti-English sentiment did not falter through 1916.

In the 1916 election, the Republicans decided to gamble with the isolationist wing of the party. William Borah, a incorrigible Senator, and a firebrand isolationist, was nominated for their candidacy. Borah’s campaign focused on keeping America out of European affairs, and embracing the ‘Nation with Two Oceanic Walls’ ideals that had been celebrated for years prior. He believed that America should keep to America’s region of the world, and that by building efforts here at home to focus on home, America’s prosperity would be unending.

Wilson attacked Borah for his ‘cowardly stance’ in the face of ‘German aggression’, but Borah hit back saying that both alliances were playing America like a fiddle, and that America was above getting involved in Europe’s petty wars over nobility and imperialism. With threats at home, including ‘the specter of Socialism’, and other ‘domestic threats to American prosperity’, Borah believed that America ought to be treated as a world within itself.

The American public seemed to agree, as William Borah was elected to the office of the President of the United States in November 1916, soundly defeating President Woodrow Wilson, whose growing interventionist ideas were soundly refuted by the American public. They wanted no part of a foreign war.

Thus, Borah announced his intentions to begin to move to rescind the availability of loans and materiel to the Entente. While Japan needed no American loans, and was, at the time of the war, a creditor nation, Britain was concerned that if America ‘turned off the tap’, it would be a catastrophic set-back for the war effort. Add in the growing casualties of the war, Britain began to look for an exit to keep their Empire together, and prevent revolution that seemed ever the more likely in Russia by the day.

Japan and the United Kingdom both made clear that they were willing to withdraw from the war against Germany in exchange for certain concessions by late November 1916. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance implied to Germany in late November 1916 that they would seek peace with Germany on the condition that they recognized the territorial seizures undertaken by both Empires, and that Germany pledge not to take any territory from Belgium in a peace treaty.

The Germans were interested in the proposal. The Western Front was a static bloodbath, and even if France was uninterested in ending the war (blood of the German must flow, in their minds), Germany could lessen a significant naval thorn in the form of Japan and the United Kingdom. The Belgian clause of the peace agreement was a bitter pill to swallow for Berlin, but it was admitted in higher level circles in both the military and civilian elements that seeking a separate peace and acquiescing to the demands given were the better solution than fighting to exhaustion.

Sanity reigned, and the British and Japanese exited World War I on December 3rd, 1916, with Britain’s dominions following three days later. All the territorial acquisitions of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance were recognized by the German Empire. While Germany had made peace with Britain and Japan, none of the other Central Powers had. Germany’s decision alienated her in the courts of Vienna and Istanbul, while Tokyo and London’s actions deeply alienated them in Paris and Rome.

Britain’s withdrawal lead to the rapid collapse of the Calais pocket as British troops left France en masse. With a lack of British naval support, the French were required to reorganize their war effort, realizing that now they were on the naval back-foot, as the Kaiserliche Marine had an incredibly narrow margin over them, enough to annoy the French.

By the start of 1917, the Ottomans were teetering on collapse, the British having advanced almost into Anatolia, armed to the hilt and ready to bring down the Ottoman Sultanate. Russia was teetering on the brink of revolution; her armies weary and ready to lay down their arms and find peace. Vladimir Lenin and his cadre of Bolsheviks were stirring up a storm, and Russia was ready to break. France was on the ropes herself, her fields bloodied with the bodies of youth, and with her officers unsure of how to proceed against the Hun menace after the British betrayal.

Britain licked her wounds, and steeled herself in the face of growing Irish nationalism. The Easter Rising of April 1916 had been a major factor in Britain seeking to exit the war, so that she may deal with the issues growing at home. However, the now threat of an unchallenged Germany caused a significant rise of alarm in Britain, and the move for a rapid naval expansion. Britain’s attentions there-after became two-fold—deal with the rise in nationalism in India and Ireland; and built an untouchable navy.

For Japan, their attentions had not lingered on the war for quite some time, as affairs in Asia had grown into a serious situation must faster than originally anticipated…

By the start of 1916, the Western front was a grinding mess of unmovable trenches, with neither side managing to get the leg up on the other. While Germany had the natural upper-hand going into the year, her salient to the seat which had cut off supplies to Calais and Western Belgium had done very little to help the situation as the Kaiserliche Marine had not been able to prevent Britain from delivering supplies to the small pocket.

The Eastern Front was, in fact, very fluid. In September 1915, German forces were still slogging east through Congress Poland, however, by the time of the winter setting in a few scant months later, German forces had made it as far as Riga and Minsk, and settled in for Mother Winter’s steely bitterness.

For Austria, their fortunes against all their adversaries had been less than successful in the grand scheme of things—while Serbia had fallen in fall 1915, Italy had entered the war on the side of the Entente, and was causing issues for the Austrians. As well, they had failed to capture back most of their land from Russia, causing for Germany to ‘de-facto’ occupy chunks of Galicia-Lodomeria.

Bulgaria, which had joined the Central Powers in 1915, had been given a lion’s share of Southern Serbia for their contributions. However, the final ersatz ally of the Central Powers, the once glorious Ottoman Empire was suffering an unbelievable number of set-backs in their efforts to conquer Britain’s territories in Africa and Arabia. The British had reversed the Ottoman invasions of Egypt and Kuwait, and had made great strides in beating back the Turks—by the start of 1916, the British were in the Levant, Hejaz and Iraq causing significant issues for the Turks.

The Russians, despite their numerous defeats by the Central Powers, had managed to turn things around in the Caucasian Mountains, where they drove the Turks back across their own border, and had advanced into Trebizond, south to Lake Van. Their advancements into Turkish territory would be reversed by January 1917, and the border would go back to being static.

…

In the United States, the Presidential Election of 1916 was in full-swing. President Woodrow Wilson was campaigning on the platform of ‘He Kept Us Out of the War’, and was appealing to the sense of American exceptionalism at its finest—the United States was having an increasingly complex relationship with both the Entente and the Central Powers.

The Lusitania, an American cargo ship, was sank by the German Navy in 1915, sparking outrage amongst Americans whom felt that their rights as a nation were violated. Within weeks of that, false allegations of British diplomats attempting to bribe U.S. government officials enflamed anti-British sentiment in the United States as well—Irish-Americans, German-Americans and Jewish-Americans all patently disliked the British Empire. The Irish-Americans were largely expatriates whose families had been forced out of Ireland during the Potato Famine 70 years prior; the German-Americans and Jewish-Americans either had great ties back to Germany, or felt that Britain did not sufficiently represent their interests as groups.