These vessels were also well armed with all calibers of secondary battery guns. The McCulloch's boilers and engines were above the water-line and entirely unprotected, so that she was unfit for the fighting line.

Consul Williams brought information that the greater part of the above fleet, some smaller gunboats escepted, was mobilized in Manila Bay; that there were three or more batteries along the water front of the city; two on Sangley Point, protecting the navy yard at Cavite, one or more at Mariveles, two or more on Corregidor and Caballo Islands and one or more on the south shore of the entrance to the bay, all of six- to nine-inch caliber. Mr. Williams had also been credibly informed that the customary entrance to the bay between Corregidor Island and Mariveles, and the waters in the vicinity of Cavite had been extensively mined. He further stated that a large merchant transport, the Isla de Mindanao of the Compania Transatlantica arrived the day before his departure, laden with munitions of war, including coast guns, automobile torpedoes and submarine mines, the latter intended for the larger entrance to the bay south of Corregidor.

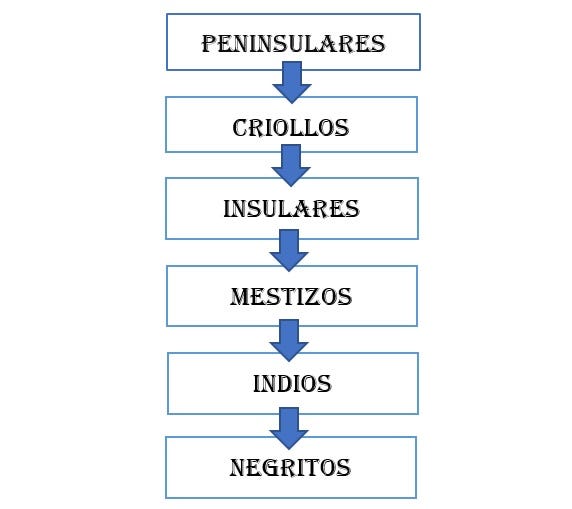

Assuming, then, that each shore battery contained at least two guns, which afterwards proved to be an under estimate and that the Spanish Admiral was going to make his stand in Manila Bay, Commodore Dewey had to expect to draw the fire of at least five batteries, of ten 6-inch guns or larger, whichever entrance to the bay he chose and whether he found the Spanish fleet at Manila or Cavite. Since a commander, when entering a theater of operations, must look to the contingency of the whole enemy's force being combined to the best advantage against him, we may now tabulate the elements of the opposing forces as they must have presented themselves to Commodore Dewey when he started for Manila.

We must add to this the probability that the entrances to the bay and the approaches to Manila and Cavite were strewn with submarine mines. Hence, assuming that the Spaniards were fairly good marksmen and that the best disposition would be made of their material, it must be conceded that the apparent odds were not in favor of the United States squadron.

On the afternoon of the first day out from Mirs Bay all hands were called to muster on each ship and the following proclamation of the Governor-General of the Philippines was read:

"SPANIARDS—Between Spain and the United States of North America hostilities have broken out.

"The moment has arrived to prove to the world that we possess the spirit to conquer those who, pretending to be loyal friends, take advantage of our misfortunes and abuse our hospitality, using means which civilized nations count unworthy and disreputable.

"The North American people, constituted of all the social excrescences, have exhausted our patience and provoked war with the perfidious machinations, with their acts of treachery, with their outrages against the law of nations and international conventions.

"The struggle will be short and decisive. The God of Victories will give us one as brilliant and complete as the righteousness and justice of our cause demand. Spain, which counts upon the sympathies of all the nations, will emerge triumphantly from this new test, humiliating and blasting the adventurers from those States that, without cohesion and without a history, offer to humanity only infamous traditions and the ungrateful spectacle of Chambers, in which appear united insolence and defamation, cowardice and cynicism.

"A squadron manned by foreigners possessing neither instruction nor discipline, is preparing to come to this archipelago with the ruffianly intention of robbing us of all that means life, honor, and liberty. Pretending to be inspired by a courage of which they are incapable, the North American seamen undertake as an enterprise capable of realization, the substitution of Protestantism for the Catholic religion you profess to treat you as tribes refractory to civilization, to take possession of your riches as if they were unacquainted with the rights of property, and to kidnap those persons whom they consider useful to man their ships or to be exploited in agricultural or industrial labor.

" Vain designs! Ridiculous boastings!

"Your indomitable bravery will suffice to frustrate the attempt to carry them into realization. You will not allow the faith you profess to be made a mock of; impious hands to be placed on the temple of the true God; the images you adore to be thrown down by unbelief. The aggressors shall not profane the tombs of your fathers, they shall not gratify their lustful passions at the cost of your wives' and daughters’ honor, or appropriate the property your industry has accumulated as a provision for your old age. No, they shall not perpetrate any of the crimes inspired by their wickedness and covetousness, because your valor and patriotism will suffice to punish and abase the people that, to be civilized and cultivated, have exterminated the natives of North America, instead of bringing to them the life of civilization and of progress.

“Philippinos prepare for the struggle and, united under the glorious Spanish which is ever covered with laurels, let us fight with the conviction that victory will crown our efforts, and to the calls of our enemies let us oppose with the decision of the Christian and the patriot, the cry of 'Viva Espana.'

"Your General,

"BASILIO AUGUSTIN DAVILA."

Immediately after the reading of this remarkable document the crews were informed that they were bound for the Philippines to "capture or destroy the Spanish fleet." Probably no such cheers have ever before floated over the China Sea as then went up from each ship of the squadron, assuring each commander that he need not count alone on the skill and obedience but upon the eagerness and enthusiasm of the men behind the guns.

The run across the China Sea was made as directly and with as little attempted concealment as if on a peace mission. Lights were carried at night and electric signals freely exchanged; but gruesome preparations were going on within each ship. Anchor chains were hung about exposed gun positions and wound around ammunition hoists; splinter nets were spread under boats; bulkhead gratings and wooden chests were thrown overboard, furniture was struck below protective decks; surgical instruments were overhauled and hundreds of yards bandaging disinfected. The sea was strewn for fifty leagues with jettisoned woodwork unfit to carry into battle.

Leaving this squadron seeking its adversary with such grim directness, let us see what the Spaniards were doing.

A war board had been in session at Manila for two months devising means for defense. It directed the erection of batteries at the entrances to Manila and Subig Bays, the laying of mines and the mobilization of the fleet, but its members were fatally at variance as to where the fleet should make a stand. The commandant of the land forces at Manila wanted it in front of the city supported by the water-front batteries. The Spanish Admiral wished to go to Subig Bay.

The idea of utilizing the tactical advantages of some of the many channels around the other islands, maintaining a "fleet in being,” and causing the American squadron to fritter away its scanty supply of coal and provisions in vain attempts to strike a crushing blow, does not seem to have been entertained.

Manila Bay is a vast pocket in the west side of the island of Luzon, twenty-odd miles deep and nearly as many wide, with an entrance ten miles across, divided by the island of Corregidor into channels known as Boca Chica and Boca Grande two miles and six miles wide respectively. Subig Bay, thirty miles farther north, is almost exactly similar but much smaller.

On the night of the 25th of April, Admiral Montojo took his squadron to Subig Bay with a view to making his stand there. He found four 15 cm. guns (and ammunition) landed on the island at the entrance but which could by no effort possible be emplaced within a month, so remaining there only long enough to repair the Castilla, which had developed a serious leak around her stern tube, he returned to Manila Bay on the evening of April 29 and anchored his squadron off Cavite Arsenal where he prepared for battle. By that date the land defenses of Manila Bay, though not complete, were formidable. Guarding the Boca Chica were three 8-inch Armstrong muzzle-loading rifles on Corregidor Island, three 7-inch muzzle-loading rifles on Punta Gorda and two 16-cm. converted breech-loading rifles on Punta Lasisi.

Guarding the Boca Grande were three 6-inch Armstrong breech-loading rifles on Caballo Island, three 16-cm. muzzle-loading rifles near Punta Restina and three 12-cm. breech-loading rifles on El Fraile Rock. The last-named guns were taken from the gunboat Lezo and those on Caballo from the cruiser Velasco, which were undergoing repairs at Cavite, and so far from ready that all hope of getting them into service for the war had been abandoned.

The Don Antonio de Ulloa was unfit to steam. This vessel was therefore moored head and stern just inside Sangley Point, over which she could readily fire, and her inshore (port) battery was removed and emplaced on shore about a mile and a half westward, at Canacao. One of these two guns was ready for service and used on the first of May.

There was also on Sangley Point a modern fortress of masonry and earth in which were mounted two 15 cm. Ordonez breech-loading rifles. As the batteries at Manila do not enter seriously into this narrative they will not be described.

Mines are said to have been laid in the Boca Grande, off Cavite and to N.Ed. of St. Nicholas shoal. Admiral Montojo anchored his squadron across Bakoor Bay in a N.Ely. and S.Wly. line somewhat curved back toward Bakoor; his left, prolonged by the Ulloa, resting on Sangley Point and having the protection of Sangley and Canacao batteries. Besides being in shoal water, it was further protected from being turned by a line of iron lighters loaded with sand and moored together head and stern, extending in prolongation of Sangley Point, screening the ships on the left wing but in no way masking their fire. From Sangley Point to the N.Ed. the Spanish ships were disposed as follows: Don Antonio de Ulloa, Castilla, Reina Cristina (flagship), Don de Austria, Isla de Cuba, Isla de Luzon. A little inside and abreast the others lay the Marques del Duero, and possibly the Argos, but there are some indications that the latter remained at the arsenal, as did the Velasco, Lezo and transport Manila. A small armed guard was kept on each of these latter vessels and their crews distributed among the other ships, the greater number going to the Reina Cristina. The ships were cleared for action, light spars and boats sent ashore, etc., but many minor items were left to the last moment, so that the squadron went into battle without unshipping awning stanchions, hatch canopies or gangway ladders, and, excepting her gun sponsons, the Castilla was still painted white.

Two 6-inch Armstrong muzzle-loading rifles mounted on the ramparts of Fort San Felipe in Cavite Arsenal could fire over the squadron at the enemy.

By the Spanish disposition for battle, the United States squadron would have to endure the fire of three 16-cm. three 6-inch and three 12-cm. guns, a broadside of 725 pounds of metal in entering the Boca Grande or of five 8-inch, two 7-inch and two 16-cm. (898 pounds) in Boca Chica beside running the risk of submarine mines at three different points in the approach to Cavite, and would then have to fight eight or nine vessels and three shore batteries, mounting in the aggregate 36 guns and throwing a broadside of 1,800 pounds of metal or, more briefly, Commodore Dewey had actually to encounter 45 guns throwing 2,525 pounds of metal. The rapidity with which he got in touch with his adversary prevented the emplacement of several more guns at Sangley and Canacao and the mobilization of the remaining gunboats of the Spanish fleet.

On the morning of April 30, the United States squadron reached the coast of Luzon near Cape Bolinao, stood close in under the green, mountainous bluffs and coasted southward, keeping a sharp lookout for the enemy. The Boston and Concord were sent ahead at full speed as scouts and to search Subig Bay. Later in the day the Baltimore was also sent ahead to Subig, where upon arriving, she found the other two ships coming out, they having skirted all round the bay and seen nothing of the enemy. It is interesting to note that twenty-four hours earlier they would have found there nearly the whole Spanish fleet. The Baltimore stopped a Spanish schooner with a shot across her bow, but her crew professed the densest ignorance of the whereabouts of a single Spanish naval vessel.

It was nearly sunset when the squadron reassembled at the entrance to Subig Bay. Here Commodore Dewey stopped and called his captains on board the flagship to receive what proved to be their final instructions before the battle. It was a deeply impressive scene; these nine ships, dark as the clouds of a gathering storm, resting against a background of bright green hills and graceful waving palms and illumined by the golden radiance of the setting sun; over them sweeping the light land breeze wafting the perfume of fragrant tropical flowers, and from their decks the notes of their bands rising in evening concert as they played by instinctive agreement, "There'll be a hot time in the old town tonight." The stage had been set, the orchestras were playing the overture and the curtain was about to rise upon a new and terrible international tragedy.

The captains soon returned from their conference and once more the squadron was put in motion, but now the McCulloch, Nanshan and Zafiro fell directly astern of the Boston, so that there was formed a single column, flagship leading, transports in the rear. It was quickly known, almost without the telling, that Commodore Dewey was going to run past the forts into Manila Bay that night and engage the enemy as soon as found in the morning. Only a single white light at the stern of each ship was to be shown, screened in all directions but astern, to guide the next ship behind.

The night was ideal for the enterprise. The little light needed to find the entrance to the bay was furnished by a young moon which would set soon after midnight. After it had served its purpose, and the dark outlines of Corregidor Island had been discerned, a screen of passing clouds hid the moon almost constantly from view, giving the benefit of its diffused light but seldom permitting a sheen upon the water.

Early in the evening the crews were called to quarters, guns cast loose and loaded, ready ammunition ranged on deck and every preparation made for battle. Then officers and men not actually on watch were allowed to sleep on their arms till the moment for action. Most of them were still standing about the decks in low-covering groups, however, when at 10:40, the word was quietly passed around to stand to the guns. The squadron was approaching the Boca Grande. The mountainous headlands at the entrance to the bay were looming up on either hand, occasionally thrown out in bold relief by sluggish copper-colored lightning from thunder clouds behind them. A darker, nearer object lay between like a huge ill-moulded grave. This was Corregidor Island, the armed sentinel of the bay, There was a light-house upon this island and also upon its little neighbor, Caballo, but neither was lighted. Straight on the squadron now steamed at the moderate speed of 8 knots as confidently as if through a lighted channel. American officers were guiding it, and no hired pilot. It is probable that few of the navigators who conned those ships into Manila Bay that night had ever been there even in the broad light of day but United States naval officers are educated and trained for such emergencies.

Nearer and nearer loomed Corregidor as these ghost-like ships stole on undiscovered. Even to each other they were scarcely visible; each seemed alone save for a little white light ahead, always leading onward. Guns were silently trained ever toward the dark cliffs, which were constantly searched with night-glasses. At last the island was abeam,. Men held their breath and hearts almost stood still. Where were the Spanish lookouts? Where their picket boats? Where their terrible mines? The flagship ran boldly close up to El Fraile Rock in order to shape from it a good course into the bay, little suspecting that a battery had been erected upon it.

Midnight came and went and the hopes began to form that the squadron would get into Manila Bay undetected, when suddenly a light was displayed, apparently on a vessel in Mariveles Bay, then a bright light flared up on the south shore near Punta Restinga. The flagship in turning at El Fraile Rock, had disclosed her stern light toward Restinga, and at the same moment soot in the McCulloch's smokestack caught fire. The signal at Restinga Point was answered by a bright rocket on Corregidor and a flare-up light on El Fraile. The Restinga battery shot out a tongue of flame, followed by a dull report, and the rising notes of the first screaming shell came nearer and nearer till it passed with a fierce hiss high over the Raleigh and plunged in the water beyond. Another followed quickly, falling just astern of the Baltimore. Restinga battery fired no more but now Fraile opened. The Raleigh and some of the rear vessel; returned the fire; one shell, as afterward discovered, bursting directly in the midst of this battery and silencing it after it had fired but three times. Caballo and Corregidor remained silent. It is probable that at a distance of three miles the passing ships were wholly invisible except when discovered by their stern lights.

It was twelve minutes past midnight when the first gun was fired and in half an hour the whole squadron had passed out of range unscathed into the still waters of Manila Bay. Twenty miles away the sky was illumined by the lights of the city.

Excellent navigation, cool judgment, and daring audacity had foiled three batteries and knocked off 725 pounds from the enemy’s available broadside.

Concealment was no longer necessary. Bright rows of electric signal lights, red and white, were flashed from ship to ship, until the chagrined and astounded Spaniards on Corregidor must have thought the Americans were holding a water carnival. It was only the flagship setting the speed at four knots for the remainder of the night, and calling the McCulloch and transports up on her port beam.

The lights died out, crews were allowed to sleep at their guns and the squadron continued its silent journey towards its slumbering adversaries.

That the Americans would dare to run the batteries, pass over probable mine fields and be able to find their way into Manila Bay, in the dead of night, and that on the first night of their arrival on the coast, without even a casual reconnaissance to take note of these difficulties, seemed never to have entered the Spanish mind. The Spaniards had exact information by cable from Hong Kong of the sailing of the American force from Mirs Bay and were promptly informed from Bolinao and Subig of its arrival on the coast. Nevertheless Admiral Montojo seemed to think he had still a few days' grace, for among his captured effects were found an order for his ships to be ready for a grand inspection on the morning of May 1. Fires were banked on the ships and many officers were sleeping ashore at the Arsenal with their families when the dull boom of the guns at Corregidor gave warning that the enemy was creeping upon them in the darkness.

It was two o'clock in the morning when Admiral Montojo was informed by telegraph that the whole American squadron was in the bay. Steam was ordered at once, officers and men were turned from their slumber and their families and hurried aboard ship, many of them never to return alive, and every preparation was made for battle.

The night was sultry; the light breeze of the evening died out; The sky gradually cleared. In the early dawn Manila Bay was like a sheet of silver. Toward five o'clock a forest of masts became indistinctly visible to the Americans right ahead, and behind them the white houses of Manila. Close scrutiny showed only merchant vessels but almost at the same time, off to the right, was seen a number of white buildings on a low point, and beyond them a line of dark gray objects on the water. The Olympia immediately headed straight for these, followed by the squadron in column. They quickly developed into the Spanish ships off their arsenal at Cavite; one of them, the Castilla being white, showing out with great distinctness. The black merchant transport Isla de Mindanao lay in prolongation of the line to N.Ed.

Only holding his course toward the enemy’s ships long enough to make out their number and disposition, Commodore Dewey headed again toward Manila, and at 5.05 hoisted the signal "prepare for general action."

Everybody was already up, all peering through the mist of the morning. On some ships, a little coffee had been served, but, on all, the men were without breakfast; galley fires remaining extinguished. When that awe-inspiring signal went up to the flag-ship's yardarm the Stars and Stripes broke from every staff and masthead in the squadron. Twenty-six American flags floated in deadly challengebefore the incredulous eyes of awaking Manila. The McCulloch and transports were then left in the middle of the bay and the fighting column turned to starboard, sweeping slowly past the city of Manila as if passing in review, and headed directly for the Spanish fleet. At the same time the Spanish colors were displayed at the gaffs and flagstaffs of the enemy’s ships. As most of these had sent down their topmasts and left them ashore, no flags flew at their mastheads except on the Castilla, and the Admiral's flag on the Cristina. Almost immediately the batteries at Cavite and Manila opened fire, but their shells fell short and were ignored. At 5.20 the Spanish ships opened, but these shells, too, fell short, and the American squadron stood on without replying.

At last, just as the sun of May 1 rose over the hills and meadows of Luzon, the Olympia's eight-inch guns in the forward turret burst forth at 5,000 yards range as the signal that the action should begin, she herself turning to starboard and leading the column past the enemy with port broadsides bearing. About the same time two white columns of water rushed upward in front of the flagships as if from exploded mines.

The smoke from the discharge, as it sagged first away, disclosed a long lead-colored launch coming out from behind Sangley Point and standing rapidly toward the flagship, flying the Spanish flag. The secondary batteries of the flagship and Baltimore turned upon her a hail of shell, under which she stood on for awhile with plucky persistence but finally fled toward Sangley Point, where she was beached and abandoned under the guns of the fort. She was afterward claimed by the owner of the marine railway at Canacao, a Britisher who said she was only going to market at Manila, but as this man's Spanish sympathies and interests were strong, it seems quite probable that she had been impressed by the enemy as a torpedo-boat.

The battle had now commenced in earnest, and both squadrons were enshrouded in dense white billows of smoke, ever increasing in volume and incessantly pierced by red tongues of flame, while the heavy jarring reports of great guns, the bias and scream of projectiles and the sharp bursting of shells added the awful majesty of terrific noise to the vivid grandeur of fire and smoke. It soon became evident that the Spanish Admiral was content to fight in his position, which prevented his maneuvering the squadron as a whole and left each of his ships to independent action in bringing their batteries to bear. In that stubborn combat of two and a half hours the Spanish ships fought like beasts at bay. Every divisional officer in the American squadron had studied the fighting qualities of each of the enemy's vessels and every American ship, as if by common agreement, concentrated on the Reina Cristina, the enemy’s flagship and most formidable vessel. Only when guns would not bear upon her were they turned upon others and then generally upon the Cristina of equal size and armament, though built of wood. The shore batteries were permitted to keep up their incessant fire with only rapid-fire guns replying to them. The failure of these comparatively undisturbed batteries to score a single hit can only be accredited to execrable marksmanship but the poor work of the Spanish ships was undoubtedly largely due to the murderously demoralizing fire which they were compelled endure and to their bunched position.

The American squadron stood past the Spanish ships and batteries in perfect column at six knots speed, making a run of two and a half miles, then returned with starboard guns bearing. The first lap followed the five-fathom curve as marked on the charts, and each succeeding one was made a little nearer, as soundings showed deeper water than the chart indicated. The range was thus gradually reduced. Let the unprofessional reader note the great range of modern ordnance by passing here to realize that with moving guns and moving targets a whole squadron was destroyed and hundreds of people killed a mile to three miles away.

Under the miraculous providence which ordered the events of that day those six American ships steamed serenely back and forth unharmed for nearly three hours. Shells flew over them, between masts and stacks and ventilators; shells fell beside them and flung sheets of water over their guns and gunners; shells falling far short bounded and wobbled over their mastheads; shells incessantly burst above, ahead, astern and around them, but on they went unhurt; their gunners unheeding the din, loading and training and firing with the rapidity, regularity, and accuracy of machinery. Only three ships brought scars out of the fight—the Olympia, Boston and Baltimore. Fragments of a bursting shell ripped across the flagship’s bridge, passing close to the Commodore and his chief-of-staff and other fragments scarred her sides without penetrating. A well-aimed shot struck the Boston near the water on the port side aft. The shell burst in the drawers under an officer's bunk, wrecking and setting fire to the room, but prompt measures extinguished the fire. Another shell passed through this ship's foremast only a few feet from her captain as he stood on the bridge, but it fortunately failed to explode. Another small shell burst in her port hammock netting, starting a slight fire, which was quickly put out.

The Baltimore was less fortunate, being struck five times, not counting a hole in her flag at the main, a main brace (of a signal yard) shot away and a bare shave on the rim of the after ventilator. The first shell, a 6-pounder, entered under the starboard forward six-inch gun and burst harmlessly in a clothes-locker on the berth deck. The second, of the same caliber, struck at the waterline amidships on the port side and burst in a coal bunker. Another 6-pounder quickly followed some feet higher, cutting the exhaust pipe of the port ventilating blower engine on the berth deck, and exploding harmlessly, one piece sticking in the shoe-sole of the man running the blower engine. The fourth hit was perhaps the most remarkable in the annals of naval warfare, for a 12-cm. (nearly 5-inch) armor-piercing shell (weighing 55 pounds) crossed the ship’s deck and returned almost to the point of entry, passing each time through a group of fourteen men without actually hitting a soul. This shell entered the starboard bulwarks abreast the main rigging, a few inches above the spar deck, ploughed up the wooden deck planking and struck a steel beam, cracking it through. The beam deflected the projectile upward so that it passed sideways through both sides of the steel combing of the engine room hatch, after which it was again pointed straight, then struck the left recoil cylinder of the port 6-inch gun and glanced from this to the inside surface or the semicircular gun-shield. This changed its course nearly 180 degrees, and it flew again across the deck, struck an iron ladder on a ventilator, fell to the deck, spun rapidly on its side and rolled into the waterway scarcely twenty feet from where it first entered. On its first trip this shell struck a box of 3-pdr. ammunition, bursting several charges. Fragments of these and splinters from the deck wounded two officers and seven men, all so slightly that many of them continued their duties after surgical attendance on the spot. The officer commanding the division, who received a slight wound in the arm, was standing upon the engine-room hatch (in order to see over the bulwarks) when the shell passed through it. He and several iron gratings over the hatch were thrown upward by the blow. A powderman, near whom the shell passed upon its return trip was rendered instantly unconscious from the windage, falling flat upon his face and not fully recovering consciousness for twenty-four hours. The port gun was disabled, for when fired again it would not run out to battery on account of the deformed cylinder. The last shell to score a hit on the Baltimore struck the water on near her port bow, ricocheted end-aver-end above the heads of an 8-inch gun’s crew and past the captain and navigator on her bridge; then tumbled into the cowl of a ventilator.

In the early part of the action the Baltimore's two quarter-boats were blown to pieces by the blasts of her own guns, and their remnants were cut adrift, making a gruesome wreckage in the squadron's path.

The pall of smoke which hung between the contending vessels prevented the effect of many shots from being seen, but close scrutiny with glasses gave the comforting assurance after the first twenty minutes that the enemy was being hit hard and repeatedly, and as the range grew less so that gun's crews could watch the fall of their shots with the naked eye, many an exultant cheer went up from every ship. Naked to the waist and grimy with the soot of powder, their heads bound up in water-soaked towels, sweat running in rivulets over their glistening bodies, these men who had fasted for sixteen hours now swung shell after shell and charge after charge each weighing a hundred to two hundred and fifty pounds, into their huge guns and trained these monster engines of destruction, fifteen to twenty tons, all under a tropical sun which melted the pitch in the decks, utterly unconscious of fatigue, and oblivious of the fact that each and everyone of them was in momentary danger of being mangled out of all semblance to humanity. Such is the exaltation of battle! Even greater was the endurance of those below, imprisoned beneath huge battle and behind water-tight doors, facing the white heat of furnace fires and breathing an atmosphere at two hundred degrees; knowing not the tide of battle; knowing not if the shocks which continually shook their ships were from their own guns or from the enemy’s shells, but knowing full well that for themselves in case of disaster there was no escape, but death amid the horrors of scalding steam, searing fire and in-rushing water.

Toward the end of the action the Cristina stood out as if unable to endure longer her constricted position, but the concentration of fire upon her was even greater than before and she turned away like a steed bewildered in a storm. It was seen that she was on fire forward. Then a six-inch shell tore a jagged hole under her stern from which the smoke of another fire began to seep out. Right into this gaping wound another huge shell plunged, driving a fierce gust of flame and smoke out through ports and skylights. Then came a jet of white steam from around her after smokestack high into the air, and she swayed onward upon an irregular course toward Cavite until aground under its walls.

The Spanish Admiral's flag was now hoisted upon the Isla de Cuba, and many guns were turned upon it, but the excellent target presented by the white sides of the Castilla held for her a large attention. Shell after shell burst in her hull, and the dark columns of smoke which followed told of deadly fires started.

Then the Duero pointed her long ram out past Sangley Point, either preparing to use a torpedo or endeavoring to escape, but she received the same storm of shells as the' Cristina, and retired on fire.

It was now 7.30. The Cristina was out of action and on fire, the Castilla’s guns were almost silenced, and all the rest of the Spanish fleet except the Ulloa were retiring behind the mole at Cavite Arsenal, whence they could not possibly escape. It was at this time erroneously reported to Commodore Dewey that his ammunition was running short, so at 7.35 the flagship signaled "Withdraw from action," followed by "Let the people go to breakfast." Ten minutes later the American squadron stood out beyond the range of the persistent shore batteries and came to rest. Battle gratings were lifted and grimy men crowded on deck, clambering upon every available projection on the blistered, flame-scorched sides of their ships to cheer each other like demons released from Hades. Commanding officers were then called on board the flagship to discuss plans of final destruction.

Meantime let us look at the Spanish side. Having part of the Velasco’s crew and additional marines from the Arsenal, the Reina Cristina is said to have gone into action with 493 men all told. As soon as the American gunners got her range the carnage was dreadful, but there were plenty to fill the dead men's places at the guns, and they were fought gallantly and without slacking for more than half the action. Admiral Montojo was posted upon the characteristics of all his opponent’s ships except the Baltimore. She was a "Johnny-come-lately" in the squadron, of whom he had received but meager information. Her great, apparent size, her heavy battery and her immunity from injury finally convinced him that she was a battleship. He then directed the Cristina’s battery upon her with armor-piercing shells.

In the early part of the action a shell burst in the Cristina's forecastle, almost annihilating four rapid-fire guns’ crews; a fragment striking the foremast and flinging splinters upon the bridge which disabled the helmsman. Lieut. Don Jose Nunez immediately took the wheel and steered the ship until her steering gear was destroyed. The next heavy shell burst among the crew's lockers on the orlop deck and started a fire which was with difficulty extinguished. Then an eight-inch shell pierced the shield on the port forward 16 cm. gun and burst in the midst of the gun’s crew. This was just in front of the bridge. Under his very feet Admiral Montojo saw in a moment of time a gun disabled and twenty men torn to pieces.

The Spanish Admiral seems at last to have realized that to continue the fight, where he was meant certain annihilation, and with desperation he headed the Cristina toward the American flagship. She could more easily have faced a hurricane. Shells of all calibers from every American ship plunged into her fore castle and swept her upper works. An eight-inch shell, bursting forward started anew the fire on the orlop which its companion shells now prevented from being extinguished, and it was necessary to turn the ship’s bow from the enemy in order to fight the flames. As she swung broadside on a large shell plunged into her super heater and burst, scalding and killing a gunner’s mate and twelve men. Next came a six-inch shell which burst in the ward room, already turned into a bloody hospital, tearing out the after part of the ship, killing the wounded and starting a new fire. Then the mizzen topmast and spanker gaff came down with a crash, bringing the Spanish ensign and Admiral Montojo's flag to the deck, but these were quickly rehoisted on other halyards.

A shell now carried away the steam steering gear on the bridge and an attempt was made to connect the hand-wheel aft, but the ship swung stern to the enemy and was exposed to a raking fire. The next large shell which hit killed nine men. Then came the

coup de grace. An eight-inch shell plunged into the stern, annihilating the hand steering gear and the men working upon it, tore its way on a long slant to the engine-room and cut the exhaust pipe-leading to the condenser.

The Cristina drifted aimlessly onward toward Cavite followed by an undiminished hail of projectiles. Her blood-drenched decks were cumbered with redly dripping human fragments and writhing and groaning wounded. Only one gun captain and another petty officer, with a few unwounded sailors, now went from gun to gun in the waist of the ship loading and firing. Flames were licking their way from bow and stern, consuming the wounded as well as the dead. The after magazine was now flooded, orders were given to scuttle the ship, and the Cuba and Luzon were signaled to rescue the crew. The Duero also assisted, and boats from the arsenal, but scores of men were imprisoned beneath a roaring furnace with only the choice between rushing up to die in its devouring flames or remaining below to drown in the rising waters. The captain, Don Luis Cadarso, was killed by a shell while superintending the rescue of the survivors. All who could be gotten out of the doomed ship were landed at Cavite and mustered. One hundred and sixty answered to their names, and of these ninety were wounded. Thus, out of 493 on that ship, 333 brave sailors were dead or missing and go more were

hors de combat.

Admiral Montojo estimates that the Cristina was hulled seventy times before he left her. An officer who remained on her to the last moment says she was hit far oftener.

The Castilla remained at anchor during the action, fighting her port guns until her port side was riddled, then by chance her chain was cut and she swung around till her starboard guns bore. Being a wooden vessel she was repeatedly set on fire and her gunners had frequently to leave their guns and subdue flames. About the middle of the action, after her wardroom had become filled with wounded, a large shell burst in it, killing nearly all and starting a fire which could not be subdued. The after magazine was then flooded. A little later another shell of large caliber struck her amidships near the water-line, bursting in the machinery and starting another fire which finally got beyond control. Toward the close of the action a third large shell burst under the forecastle and set fire to her forward. The forward magazine was cut off by flames so that it could not be flooded and the ship's destruction became a certainty. A prearranged distress signal was then hoisted and boats put off from Cavite to rescue her crew. Her captain and 23 men had been killed and 80 wounded. At about ten o'clock the last man who could be found alive was taken out, her flag was hauled down and she was abandoned, burning and sinking.

When the Cristina sagged out of action the next best target was the Austria and many more guns were turned upon her. Her bridge and pilot-house were completely wrecked by heavy shells. The steering gear was demolished and the man at the wheel killed. At this time, too, the gunboat Duero, after her dash, was running for cover with a fire under her forecastle. The Austria, having now to be steered below decks, was scarcely under control. Admiral Montojo realized he was completely beaten and made signal to retire behind the arsenal and scuttle and abandon the remaining ships. The demoralization is indescribable. Ships crowded helter skelter into Bakoor Bay, grounding and anchoring anywhere when out of sight of the enemy. The sea-valves of the Austria, Cuba and Luzon were broken, and officers and men hurried ashore without stopping for personal effects. Photographs of wives and daughters were afterward found upon their bureaus; silver toilet articles and

bric-a-brac remained untouched; money lay scattered upon cabin floors. Admiral Montojo had a slight wound in his leg dres5ed in Cavite, then took a carriage and fled to Manila.

At this time the American sailors were at breakfast, the ships drifting idly upon the placid waters of the bay, shells from Manila and Sangley falling harmlessly some cable lengths away. While the captains were with the Commodore a strange steamer was sighted coming up the bay and keeping close to the Cavite side. When the conference broke up the captain of the Baltimore was directed to intercept this vessel while the rest of the squadron stood in to complete their morning’s work. The Baltimore was therefore considerably in advance of the squadron standing directly in toward the beach across the steamer's bow, when the latter was discovered to be a merchantman, and the McCulloch was directed to stop her, while the Baltimore was signaled to lead into action. Sounding as she went, she got safely within 2,500 yards of the beach, then turned to port at 11.05 and steamed slowly, signaling "Permission to attack enemy's earthworks." Then followed for ten minutes a duel with the batteries which is attested by the onlooking squadron (not then within fighting distance) as one of the most magnificent spectacles of the day. The big cruiser, slowing and creeping along at a snail's pace, seemed to be in a vortex of incessant explosions both from her own guns and the enemy’s shells. At times she was completely shrouded in smoke and seemed to be on fire, while every shell she fired was placed in the earthworks as accurately as if she were at target practice. Canacao battery was the first to fall under this deadly fire. Its embankments of sand, backed by boiler iron were torn up and flung into the faces of the gunners until panic took hold of them. Hauling down their flag, they tumbled into an ambulance and drove madly to the protection of Fort Sangley. The whole fire of the squadron was then concentrated upon this fort. Its ramparts seemed to be in an incessant upheaval of earth from which dust and smoke and fire rolled away as from a volcanic crater. Three times its guns seemed silenced and the ships reserved their fire, only to see the plucky Spaniards begin again. At last, when by Spanish accounts, a gun was disabled and six men killed and four wounded the Spanish flag came down and a white flag was raised in its place.

There remained only the cruiser Ulloa, moored just inside Sangley Point. She had received some punishment in the first engagement, but her commander had not obeyed Admiral Montojo’s signal to "scuttle and abandon." We cannot too highly admire the courage of this man, commanding a little cruiser unable to move and already severely crippled by the enemy’s guns, who, with an order from his commander-in-chief to

sauve qui peut, stuck to his ship for three hours within a stone's throw of the beach and safety, calmly awaiting the onslaught of the whole American squadron.

The Baltimore, drifting past Sangley Point, received the fire of the Ulloa and at once returned it with a raking rife. The Olympia, passing outside and abreast the Baltimore, also openedon her. The Raleigh, passing beyond both, turned Sangley Point and threw in a deadly cross-fire. The intrepid ship was literally riddled with shells, nearly every gun being dismounted or disabled. At length the crew swarmed over her unengaged side and swam for shore. Then she gave a slow roll toward her executioners and sank beneath the waves. Three masts remained in sight to mark her grave, from one of which still flew the Spanish flag.

Meanwhile the Boston advanced beyond the Raleigh toward the arsenal, past the blazing Castilla, but was stopped by shoal water. The Concord entered Bakoor Bay to destroy the transport Isla de Mindanao which had been run aground. She opened fire with her six-inch guns and the transport was quickly in flames, her crew deserting her and taking to the woods. The little Petrel alone was able by her light draught to steam in to the arsenal, which she did with gallant dash. Those on the less fortunate ships held their breath, expecting to see her draw the fire of all the hidden Spanish gunboats but after she had fired a few shots, which were not returned, the last Spanish flag was hauled down, and at twenty minutes after noon, a white flag was hoisted on the arsenal sheers and the Petrel signaled “The enemy has surrendered."

Sending his chief-of-staff to the Petrel to receive the surrender, Commodore Dewey steamed at once to Manila, followed later by the Baltimore, Raleigh, Concord, McCulloch and transports. The squadron anchored off the city as unmolested as if in time of peace. The sun went down amid the usual evening concert and one could scarcely realize that he had just participated in the most complete naval victory of modern times.

Yet over at Cavite lay ten warships burning, exploding, and sinking; a squadron annihilated; a navy yard captured and nearly four hundred Spanish dead and wounded. On the American side not a ship disabled; not a man killed.

It is impossible in closing to refrain from summing up the results already apparent of this remarkable victory.

It gave a prestige to the American arms at the very outbreak of hostilities which commanded the respect and admiration of nations which might otherwise have been hostile.

It swept all Spanish naval force from Pacific waters, relieving even the most timorous from all fear of a raid upon our Pacific coast or Pacific commerce.

It gave the United States a vast and prolific territory to hold for ransom or retain as indemnity.

It necessitated and brought about the capture of Guam and the annexation of Hawaii.

It diverted the Cadiz fleet from Cuba, thus permitting the whole Atlantic cruising force to concentrate on Santiago and Cervera.

*The writer has endeavored to reconcile many statements of Spanish casualties. Governor General Augustin's official dispatch to Madrid, as published in the

New York Herald, states that the total loss was 618. Admiral Montojo's official report, as published in

El Imparcial, Madrid, states that 381 were killed and wounded. Statements of surgeons and other officers who were on the ships and in the hospitals add up to very nearly the higher figure, as killed or missing alone.

Credit additional:

Digital Proceedings content made possible by a gift from CAPT Roger Ekman, USN (Ret.)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-89861170-56b008335f9b58b7d01f9b15.jpg)