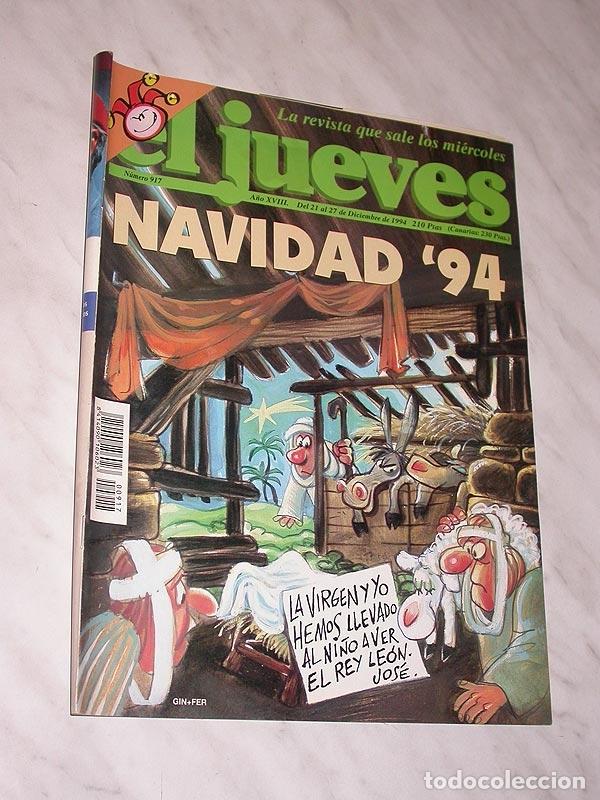

"I went with Mary and the kid to watch the Lion King

Joseph".

169. First Boyer Ministry (1993-1997) -1-

Without a shred of a doubt, Miguel Boyer is today remembered as the best Spanish prime minister. During his first tenure he had not only to deal with the challenge offered by the Nationalist coallition which, eventually, would result in the Catalan independence process of 1999, but also with the beginning of the crisis that would put the Spanish monarchy at stake. His experience as minister of economy, treasury and commerce with Garrigues Walker (1982-1984) gave him knowledge of the Spanish parliamentary system and help him not only to keep both challenges under control but also to keep them within peaceful and democratic limits in spite of the provocations presented by the radicals. He established a very centralized and highly effficient government following the example of the last Liberal Prime Minister. However, he would be also remembered for his cautious, managerial approach to governing, reacting to issues as they arose, and was otherwise inclined to inactivity.

His tenure started with a confrontation with the United States when Boyer canceled the contract to buy the

Sikorsky H-92 Superhawk to replace the aging

Westland Sea King, forcing the payment of $500 million of cancellation fees. Instead of the Superhawk, Boyer selected the Westland's new

Merlin. Thus, a few months later, the Boyer government announced the purchase of 25 EH-101 helicopters for the Navy plus 20 EH-101 for the Spanish Army to replace the

Aérospatiale SA 330 Puma. This cancelation of the Superhawk contract, signed by Verstsrynge in 1987, caused an inmediate worsening of the US-Spain foreign relations, as Boyer returned to the Anglophile policies of his predecessor. Following in that direct, she signed in early 1944, with the British Prime Minister, the fellow Liberal David Steel, the Anglo-Spanish Trade Treaty and made it a big victory in the press. During the talks, the Spanish delegation also broke a deal with British Aerospace to take charge of the modernization of the EF-18 Hornet fighter-bombers, which would become one of the most controversial moves of Boyer, as we shall see in due time.

Furthermore, as part of the efforts against the large national debt that had been inherited, Boyer fired the governor of the Bank of Spain, Luis Ángel Rojo, who was replaced with Carlos Solchaga on February 1, 1994. Rojo's policy of high interest rates, inherited from his pedecessor, Mariano Rubio, to achieve zero percent inflation was quite unpopular, and thus Boyer waited little to replace him after Rojo refused to forgo his zero percent inflation target and end the punishingly high interest rates.

He also trimmed the civil service, replacing the older civil servants with the younger and talented generation that the Spanish universities were churning out in considerable numbers by then. This "purge" also afected several deputy ministers that were deemed to be to inclined to the right. These measures were to prove a great public relations sucess for Boyer, who was highly praised in the press. Thus began the creation of the legend that surrounds him since then.

His first budget, however, was described as a "mild and tame". It aimed mainly at reducing the deficit to 3 percent of

Gross National Product (GNP) within three years, and brought in modest cuts, mostly to defence spending (this would lead to the cancelation of the Barret M92 contract, replaced by the Russian rifle OSV-96). This tendency would be kept until the terrorist attacks of 2005. Thus, Boyer's mesures would keep reducing the military spending to such a point that he would be accused of having reduced the Spanish Armed Forces to merely "

a bloated police force". Boyer would also claim, during a TV interview, that "

major cuts to government spending outside of defence are out of the question" and placed his trust in the economy. In his view, the growth of the Spanish economy would be enough to annhilate the deficit without any further cuts. Thus, he favoure the increse of the Spanish exported by embracing globalization and free trade with as many nations as possible. However, in spite of Boyer's good intentions, the stock market reacted quite negatively to his annoucement. Many economists claimed that Boyer was doing nothing to reduce the debt problem, but the prime minister went ahead with his plans. On his part, Mayor Oreja attacked the government and demanded far more drastic cuts, but Boyer, supported by Ardanza in the Cortes, ignored this view. However, this would change when many foreign investors began to express about buying Spanish bond. To change this, in 1995 the Bank of Spain raised the interest rates in order to attract investment, but this, in turn, damage the government's ability to collect taxes and increased the doubts among investors that they would be repaid. Thus, by late 1994, Boyer decided that a deeper change was needed and a more drastic pack of cuts was implemented, going even further than the cuts proposed by Mayor Oreja.

In November 1995, the radical Nationalist politician Angel Colom won the Catalan elections and became the new president of the Generalitat and began to demand a referendum at once. Boyer decied to use this as an opportunity to destroy the Catalan sovereignty movement once and for all.

Colom was a "hard separatist", determined to press for the total independence of Catalonia, but Boyer made the mistake of cosnidering the "mild separatists" like the Socialist Joaquin Nadal, as the "enemy" too and then compounded this mistake by courting the Conservative leader in Catalonia, Alejo Vidal Quadras, who was despised by even the less Catalan nationalists for his radical views on Spanish and Catalan nationalism. If Boyer had wanted to secure the victory of Colom, he could not have it helped in a better way. However, the Spanish prime minister was convinced that the separatists were to suffer such a defeat that it would be the end of Catalan separatism and an excellent warning for the Galician and Basque nationalists.

The Canadian economic meltdown of 1996 semeed to shake Boyer's complacency and forced him to change his policy. Deeped cuts were introduced in all of the departments of the government in spite of the complaints of the ministers. He had no troubles to replace his Defence Minister, Julián García Vargas, with Gustavo Suárez, and implement a strict control of the backbenchers and Cabinet ministers, in such a way that he was privately called "the Rockefeller of the dictators". Even if Boyer was quite reluctant to introduce in social programs, the Social spending fell from 20.35% in 1993, to 18.35 percent in 1996 and 16.94 percent in 1998. It would not be until 2003 when the social spending rose again. In spite of this, Boyer's popularity remained untoched.

Then, the 1996 Catalan referendum made Spain to shake.