11. Spain in the new century.

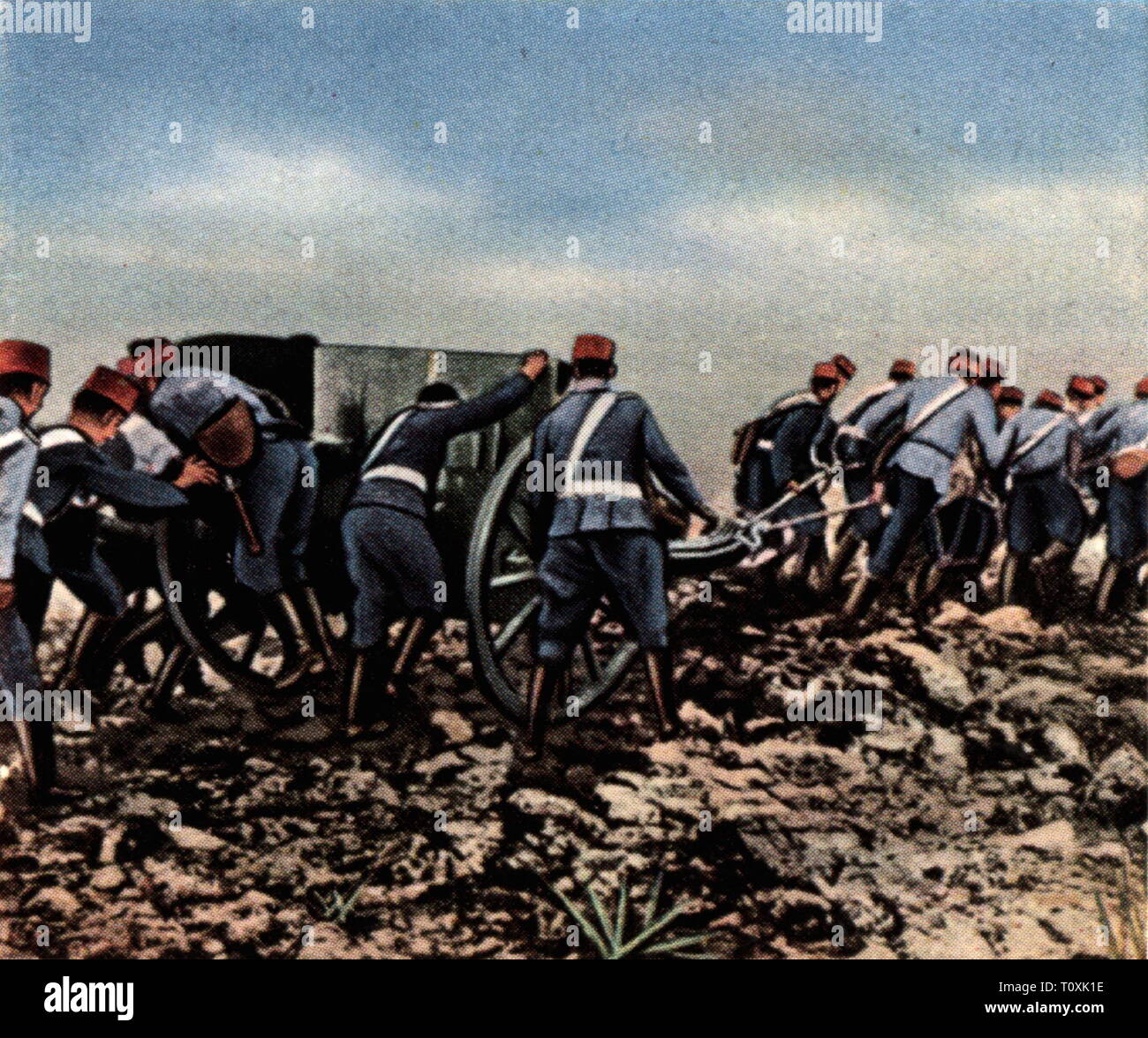

Since the end of the Napoleonic wars and the American Independence Wars, Spain had enjoyed a peaceful period that would was interrupted by the Civil War of 1848-1849, the royalist repression (1849-1856) and the short First Morocco War (1859), which had a visible effect upon the growning of the Spanish population, that would be hit hard again by the famine crisis of 1880-1885 (1), made worse by the cholera outbreak of 1885. The colonial wars in Cuba would kill 65,000 soldiers and, to this death toll, we must add the famine crisis that plagued the country between 1885 and 1890, that caused a rise in the mortality rate, which grew to a 2,5% and remained stable there until 1894, when it fell to 2,1% (2). By 1920, the mortality rate in Spain was 1,78%, while the birth rate would go down from 3,4% in 1905 to 3,03 in 1920. We must to keep in mind that between 1882 and 1900 230,000 Spaniards emigrated towards South America and France. Thus, in spite of this troubles, the Spanish population grew from 1860 to 1900. If in 1860 Spain had a population of 15,6 millions in 1900 had grew to 20,5 (3).

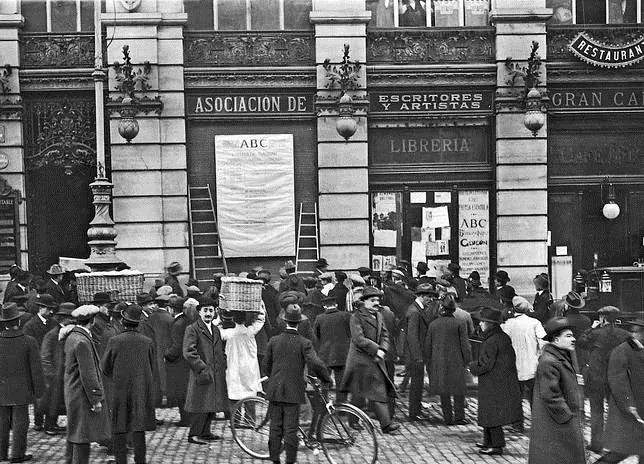

With this growing population, the economic and social crisis mutiplied themselves too. The quality of life had improved, indeed, but the mentioned troubles forced to an increased inmigration too, so, while in the 1890s around 15,000 Spaniards a year left Spain for the Americas and France, by the 1910s this number had grew to 36,000, until it fell down in the 1920s to 14,000 and vanished totally by the 1930s. The internal emmigration will be also a factor in the rise of big cities like Madrid and Barcelona. If by 1877 45,4% of the population of Madrid and 19,5 of the inhabitants of Barcelona were not born in those cities, by 1910 the percentages were 39,9% in Madrid and 29,3% in Barcelona. If we analyze the overall figures of Spain we shall see a small rise from a 8,5% in 1877 to 10,2 in 1910.

How were the economy and the politics that had to back this growing population? The industry and services were well developed by 1882-1890, but the strain seen during the famine of 1881-1885 would go on from then on during the 1890s, when an imbalance between industry and population was clearly seen. In spite of the best efforts of the government, there was a huge difference in the industralization process of the different Spanish regions, as Catalonia gathered the bulk of the industry (with the heavy industry and the shipyards placed in the Basque Country and a small industrial settlement in Valencia) and of the banking system. The thriving steel and mining industry in Málaga, Sevilla and Huelva of the 1870s, it had been halved by the end of the century, and it survived only by the presence of the French and British mining companies (4).

After the end of the Cuba War, the Spanish industry underwent a process of expansion. The coal and the steel industries, along with the hyropower one, were joined by the iron and textil bussines and the new banks that would help to Spanish markets well stocked at least until the end of the 1910s. Another sign of this industrial rise is the expansion of the Spanish roads. If Spain had 20,000 kms of roads by 1880, they had grown to 35,000 in 1895 and 49,000 in 1905 (5), with 1,000 new cars being bought by the Spaniards every year by 1911. The railways would also follow this rise, from 5,500 kms in 1870 to 15,000 in 1901.

(1) In spite of all the improvements of the Spanish "health services", this famine was hard enough in TTL. Thus, the cholera outbreaks of 1833-1834 and 1854-1855 killed 500,000 people, but the one of 185 "only 75,000 -120,000 IOTL- and the one of 1885 65,000 - 120,000 IOTL-). However, as there are no Carlist Wars, we avoid 250,000 deads and around 200,000 victims from illnesses caused by the war.

(2) 3% IOTL 1885-1890; 2,9% IOTL 1894.

(3) 18,5 million IOT. No Carlist Wars, no Ten Year Wars in Cuba, less damaging outbreaks, better health services... all this explains this slight change.

(4) This was so true IOT, when this industries had almost vanished by the end of th 18th but for Huelva, thanks to the French and British companies, which converted the area into a small colony. There the industry survives in better shape thanks a bit to the Spanish government and the foreign companies.

(5) 27,000 kms IOTL 1985, 43,000 IOTl 1905.

Last edited: