Stationary target at point-blank range? Not even a stormtrooper could miss that shot.Assume the torpedoes hit, the Germans will definitely lose the cruiser.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Remember the Rainbow Redux: An Alternate Royal Canadian Navy

Dammit @RelativeGalaxy7 you tease, I just got all caught up and you leave me with a cliffhanger

I'm hoping Leipzig got sunk, but I'm suspecting that the numerous references made about the unreliability of the torpedoes means that both may have failed to hit or even detonate, we shall see. Perhaps the other boat might score a kill?

I'm hoping Leipzig got sunk, but I'm suspecting that the numerous references made about the unreliability of the torpedoes means that both may have failed to hit or even detonate, we shall see. Perhaps the other boat might score a kill?

Could be a mutual kill. At 400 yards the blast from 200 pounds of wet guncotton (or 400 if both torpedoes detonated) could have delivered a fatal blow to poor fragile Boat One. Or perhaps Willie Maitland-Dougall sacrificed himself to save the boat.

But was the target Algerine, or Leipzig? Or both? If the German ships were anchored side-by-side, which was in the outboard position, and would be the one seen and possibly torpedoed by Keyes?

The area that Keyes viewed through the periscope was somewhere amidships, where the davits for the ships boats would be. Both Leipzig and Algerine carried a midship 4 inch (or 4.1 inch/10.5 cm) gun with a gun shield. Algerine had not yet landed any of her guns, as OTL, because the Germans captured her before she returned to Esquimalt.

Did both Leipzig and Algerine carry motor launches? Possibly. The best picture I can find of Algerine is inconclusive. A steam launch would have a small funnel, but a motor launch need not. Both ships carried lots of boats.

Leipzig carried her searchlights on platforms on the masts, one on the foremast and one on the main. Looking at the best picture of Algerine I can find, I think I can see at least one searchlight, on a low superstructure just behind the port forward gun.

HMS Algerine, with a pretty good picture if you zoom right in.

www.hmoob.in

SMS Leipzig

www.hmoob.in

SMS Leipzig

www.deviantart.com

www.deviantart.com

But was the target Algerine, or Leipzig? Or both? If the German ships were anchored side-by-side, which was in the outboard position, and would be the one seen and possibly torpedoed by Keyes?

The above description makes it sound like the vessels are close together to work on these all these chores.It was viewed that consolidating resources back aboard Leipzig and moving forward in their original configuration would be the most sensible course of action. In order to prepare themselves for the next part of their plan, the crews of both ships were assigned to different teams throughout the night. A detachment of armed sailors were put out into launches to guard against any vengeful civilian or military incursion, the threat of submarines was not ignored but considering the cover of darkness and the distance traveled away from any major port, it was viewed as very minor. Men were rotated into the more intact mess and berthing spaces of Algerine to be fed and catch some rest, priority given to vital personnel such as those within the engineering department. Whoever remained worked to offload any useful supplies into the holds of Leipzig alongside assisting in maintenance and repairs where required.

The area that Keyes viewed through the periscope was somewhere amidships, where the davits for the ships boats would be. Both Leipzig and Algerine carried a midship 4 inch (or 4.1 inch/10.5 cm) gun with a gun shield. Algerine had not yet landed any of her guns, as OTL, because the Germans captured her before she returned to Esquimalt.

Did both Leipzig and Algerine carry motor launches? Possibly. The best picture I can find of Algerine is inconclusive. A steam launch would have a small funnel, but a motor launch need not. Both ships carried lots of boats.

Leipzig carried her searchlights on platforms on the masts, one on the foremast and one on the main. Looking at the best picture of Algerine I can find, I think I can see at least one searchlight, on a low superstructure just behind the port forward gun.

I would not call the Algerine's searchlight mount "high on the vessel," therefore the ship in the outboard position was Leipzig.Before the Lieutenant could make sense of the situation, a ray of blinding light emerged from high up aboard the unidentified vessel,

HMS Algerine, with a pretty good picture if you zoom right in.

एचएमएस अल्जीरीन (1895) इतिहास देखें अर्थ और सामग्री - hmoob.in

एचएमएस Algerine एक था फीनिक्स स्तरीय स्टील स्क्रू स्लूप की रॉयल नेवी । उसे 1895 में डेवोनपोर्ट में लॉन्च किया गया था, बॉक्सर विद्रोह के दौरान चीन में कार्रवाई देखी गई, और बाद में प्रशांत स्टेशन पर सेवा की। 1914 में एस्किमाल्ट में उसे उसके दल से हटा दिया गया था, और 1917 में रॉयल कैनेडियन नेवी में...

S M S Leipzig 1912 Pano by Deceptico on DeviantArt

That's smart, I didn't think to look at where each ship has its spotlights. I was assuming it was Leipzig if it had damage visible on the sides since I don't think Algerine got beat up to any degree but that's even better. The Germans must be at the end of the line here with torpedoes in the water and another submarine still around. Blasted cliffhanger strikes again.I would not call the Algerine's searchlight mount "high on the vessel," therefore the ship in the outboard position was Leipzig.

End of the Line

The following excerpt has been taken from Leipzig: The Coastal Raider by Fregattenkapitän Johann-Siegfried Haun.

“As Leipzig approached the entrance to the Discovery Passage at roughly 2200 hours, an air of near total exhaustion amidst the crew was apparent. Considering we had been on alert or engaged in some manner for nearly an entire day up until that point, the resilience of the crew thus far was something that I took a great deal of pride in. With that being stated though, even the most accomplished sailors of his majesty’s navy are still only men at the end of the day. The stripping of personnel for River Forth and Algerine had left Leipzig bereft of crew to the point where the typical rotations of men between work and sleep had become uncomfortable, not considering the damage done to much of the berthing spaces which only compounded the issues. It was quite fortunate that nearly an hour later we would make contact with Algerine within Menzies Bay as our continued ability to operate effectively had been largely compromised. I distinctly recall multiple times throughout the evening where I would step out onto the bridge wings to receive a bit of reinvigoration from the pleasant coastal air, although it was not much more than a temporary remedy.

Once both ships had been lashed together and bridged by gangplanks, I immediately went to meet with Korvettenkapitän Kretschmar to discuss the events of that afternoon. I would come to find out that the detached operation had seemingly been a complete success with all identified targets being attacked and minimal casualties suffered in return. Of course the loose-lipped Canadian wireless operators in the area had been more than willing to broadcast information in regard to Algerine’s path of destruction for all to hear throughout the day, so I was not entirely surprised in the end. Kretschmar had a more complete written account of the day's events to look over; however, the night was young and all aboard still had much to do. I had ordered the officers to assemble as much of the crew as possible on the decks of Algerine as I thought it wise to give a rousing speech to the men. The delivery was very succinct, I did not wish to dally as I believe I was nearly as tired as the men under my command.

I informed the crew of the damage we had wrought upon the British Empire and the history we had made throughout the day. I communicated our plan of action going forward, that we planned to sail at first light to rendezvous with SMS River Forth up the coast, where we would continue to patrol the local sea-lanes for as long as possible. I made my heartfelt admiration for the crew's outstanding conduct as clear as possible and to reinforce such a statement, I announced that a reward would be immediately provided. For so aptly discharging their duties, each man aboard was to be allotted a serving of captured rum from Algerine’s stores. The exhaustion temporarily drained from every man in sight as they broke into a cheer almost immediately, the first trio of cheers being in my name instead of the Kaiser as was typically navy custom. This was rectified soon after with a trio of applause for Leipzig and the Kaiser alike before the crew fell in for their well deserved drink and instructions going forward.

Before the nearby officers could return to their previous duties, Korvettenkapitän Kretschmar made a strange request to us all. He wished for the commissioned officers to meet below in Algerine’s wardroom at once, this confused me to no end as my executive officer would not explain the reasoning for such a congregation. Although truth be told there was some anger swelling inside me at the perceived insubordination, I was truly exhausted to the point where such semantics did not rate highly enough in my mind. Upon our arrival, Kretschmar produced a large bottle of whiskey apparently pilfered from the former cabin of Captain Corbett alongside an equally large smile of his own. I did feel rather childish after that, although I kept that fact to myself. With our civilian navigator Mr. Baumann joining us, we lined up glasses on the wardroom table and led into a cheer of our own. All in the room partook in the amber liquor so graciously supplied by our enemy and just for a moment, we collectively basked in the glory of victory. The exhaustion we all felt was temporarily stymied by the heat in our bellies and I was taken back to fond thoughts of my nearly 25 year long navy career before the war. This was it, a moment of glory that perhaps came once in a lifetime. While the moment itself was fleeting, it is a memory I will cherish for the remainder of my life. I did not realize at the time as each man filtered back out onto the deck to oversee their duties, it would be the last time I would see many of them alive.

For my own part, I entrusted oversight of the night's tasks to my executive officer and settled into a berth aboard Algerine for the evening. Kretschmar had assured me that he had been well rested previously and that I should prepare myself for the coming morning which I did not have any qualms with. The accommodations aboard the elderly British vessel was not exactly comfortable but I likely could have fallen asleep on my feet at such a point regardless. A sailor was eventually sent to wake me around 0415 that morning for a meeting with Mr. Baumann, in order for us to set a suitable course for when we departed. When I redressed and stepped back out onto the deck of Algerine, I was met with something I had not expected, the sound of familiar music met my ears. Some of the crew milling about their tasks between the vessels had stopped for a moment to look towards the direction of the sound. The ship's band was out near the bow playing a hauntingly beautiful rendition of 'Die Wacht am Rhein'. As I recognized the various instruments missing from the ensemble, a pang of sadness struck me from within. Even with over half of the band's usual members lost in the battle with Rainbow nearly a week prior, those who remained performed their duties admirably. It was a trait throughout the crew that I still have immense respect for to this day.

It was shortly after the band finished their performance when we all heard the commotion happening on the opposite side of Leipzig. Sailors were yelling to lower boats and something about men overboard, their voices were a harsh contrast from the sounds we were just privy to. As I crossed over the gangplanks to investigate what was happening, a great force yanked my feet out from under me as I tumbled to the deck. The accompanying shower of cold water down across the deck jarred me from the shock somewhat as my mind struggled for answers. It was soon clear though, our apparently helpless enemy had finally caught up with us.”

SMS Leipzig receiving repairs and paint touchups in a floating drydock located in Tsingtao during her service with the East Asia Squadron. An inserted portrait of Captain Haun can be seen in the top right corner.

Both torpedoes from Boat No.1’s salvo struck Leipzig along her starboard side at around 0430 hours that morning, the antique guncotton warheads causing considerable damage to the vessel. The first torpedo impacted almost directly below the third funnel, blowing the hull wide open and introducing a large amount of seawater into the surrounding boiler rooms. The second torpedo struck the cruiser roughly 30 to 40 feet further towards the stern in the machinery room, laying waste to the vessel's triple expansion engines and dynamo room in the process. While such catastrophic damage was certainly fatal in the long term, the state of the crew would only prove to hasten the ships sinking. Heavy casualties amongst the thinly stretched engineering department had effectively negated their ability to perform any kind of meaningful damage control, the situation being further complicated by the fact that the watertight doors in and surrounding the damaged compartments were not able to be completely closed in a timely manner following the attack. Lieutenant Rudolf Warner took control of a hastily organized team to survey the damage below and assist in damage control efforts however, the 20 degree starboard list and supplies freshly stripped from Algerine in anticipation of her scuttling proved a detriment to team as they attempted to navigate Leipzig’s passageways. Many of these men including Lieutenant Warner would ultimately give their lives in their attempt to save the ship, the flooding eventually overtaking their efforts and trapping many below decks.

By 0440, Captain Haun had organized a damage control party aboard Algerine with additional pumps and equipment; however before they could cross over to assist their crewmates, the sloop was forced to make steam and distance itself from the cruiser as her list dangerously accelerated. The ropes and gangplanks connecting both vessels together were severed in order to not pull the sloop down, making the attempted rescue parties efforts effectively in vain. Korvettenkapitän Kretschmar, still aboard Leipzig gave the order to begin abandoning ship as the vessel took on more water, partially then through the battle damage previously kept above the waterline. Algerine lowered and towed as many of its boats as possible as Leipzig’s sailors prepared to enter the water, many of their own boats unable to be launched due to a lack of power and the angle of the hull. Haun was faced with a difficult decision in the following moments, they had almost certainly been attacked by a submarine which still lurked nearby. Every minute he spent saving men from the water meant another potential torpedo launched in his direction. Thanks to the officers memoirs though, history is well aware that abandoning his man in hostile lands was a sacrifice that Haun was seemingly not willing to make. As Kretschmar had gathered all of the survivors on the ship's tilting bow, the German naval ensign was brought down, neatly folded and three cheers were given for the Leipzig. Before the men could take to the water though, the cruiser made a sudden lurch and began to fully capsize without warning. While some men would manage to escape relatively unscathed, many more were swept under or otherwise fatally wounded by the very ship they served aboard. By the time Algerine had raised sufficient steam and maneuvered herself back around to the debris field at 0450 hours, the cruisers keel was facing upwards towards the morning sky. German sailors made note after the fact of the jagged and warped hull of Leipzig as they swam towards the safety of Algerine and her nearby boats. Over the following 15 minutes, Algerine would pull 95 of Leipzig’s 191 man crew from the waters of Menzies Bay including Kretschmar and some other officers. As dawn had broken as rescue efforts dragged on, Haun did not wish to make himself any more of a target than was necessary and reluctantly left the area. All possible speed was made for Seymour Narrows to escape any submarines still lurking in the area and safely bypass Ripple Rock while the tide would remain slack.

An offset stern view of Algerine sailing around unknown coastal waters of British Columbia sometime throughout her Royal Navy service.

At approximately 0510 hours, Lieutenant Jones spotted the sloop approaching the narrows at top speed through the periscope of Boat No.2. Utilizing the insight of Mr. Johnson, the second Canadian boat had positioned itself off Wilfred Point with its pair of bow torpedo tubes pointed east towards the opposite shore. As only the eastern side of the passage was suitable to safely transit around Ripple Rock, the submarine was set to receive a perfect broadside target as the Germans passed. Jones would intermittently raise the periscope to confirm the approach of their target which was moving directly into their kill box. At a range of just over 500 yards, Boat No.2 fired its pair of torpedoes towards the passing sloop before retracting its periscope and counting down the half minute it would take for the weapons to reach their target. Lookouts aboard Algerine were none the wiser in regard to their silent stalker until a terrible explosion rocked the ship, shortly followed by a column of water raining down across the deck. To the astonishment of the onlooking Canadians, the German vessel emerged from the plume of water seemingly unharmed to continue its march unimpeded past Ripple Rock and northward up the coast. The first torpedo had deviated from its course and drifted ahead of the sloop, passing the vessel and exploding against the opposite shore. From the lack of a second explosion, the other torpedo was though to have missed as well. While Lieutenant Jones would attempt to turn the boat and bring his lone stern tube into action, his target was far outside of torpedo range once he had prepared a firing solution. Official Canadian reports would list both weapons as having missed their target; however, information surfaced following the end of the First World War which brought new light to the engagement.

Through official German Navy reports and interviews/memoirs of the crew aboard Algerine, it was confirmed that the second torpedo fired actually impacted the sloop near the first mast yet failed to detonate. One does not have to look far in period reports regarding the lackluster material condition of vintage torpedo stockpiles in both Esquimalt and Halifax to find a cause for such a failure. Haphazard transportation across the continent and a rushed inspection of the weapons prior to their use in combat are also potential trouble areas for mechanical reliability. Whatever the exact failure of the warhead in a situation such as this, the underfunded and overstretched Royal Canadian Navy had sadly become accustomed to such faulty equipment throughout their surface vessels and the newly procured submarines. Following the failed ambush of Algerine, Boat No.2 would surface and proceed back into Menzies Bay to attempt a rendezvous with her sister ship. A large amount of flotsam from the stricken cruiser had already begun to litter the surrounding waters to the point where it was drifting out towards the Seymour Narrows itself. The sight was reassuring news for Lieutenant Jones as even if part of the German flotilla had escaped, it would seem that their primary raider had been finally dealt with.

“As Leipzig approached the entrance to the Discovery Passage at roughly 2200 hours, an air of near total exhaustion amidst the crew was apparent. Considering we had been on alert or engaged in some manner for nearly an entire day up until that point, the resilience of the crew thus far was something that I took a great deal of pride in. With that being stated though, even the most accomplished sailors of his majesty’s navy are still only men at the end of the day. The stripping of personnel for River Forth and Algerine had left Leipzig bereft of crew to the point where the typical rotations of men between work and sleep had become uncomfortable, not considering the damage done to much of the berthing spaces which only compounded the issues. It was quite fortunate that nearly an hour later we would make contact with Algerine within Menzies Bay as our continued ability to operate effectively had been largely compromised. I distinctly recall multiple times throughout the evening where I would step out onto the bridge wings to receive a bit of reinvigoration from the pleasant coastal air, although it was not much more than a temporary remedy.

Once both ships had been lashed together and bridged by gangplanks, I immediately went to meet with Korvettenkapitän Kretschmar to discuss the events of that afternoon. I would come to find out that the detached operation had seemingly been a complete success with all identified targets being attacked and minimal casualties suffered in return. Of course the loose-lipped Canadian wireless operators in the area had been more than willing to broadcast information in regard to Algerine’s path of destruction for all to hear throughout the day, so I was not entirely surprised in the end. Kretschmar had a more complete written account of the day's events to look over; however, the night was young and all aboard still had much to do. I had ordered the officers to assemble as much of the crew as possible on the decks of Algerine as I thought it wise to give a rousing speech to the men. The delivery was very succinct, I did not wish to dally as I believe I was nearly as tired as the men under my command.

I informed the crew of the damage we had wrought upon the British Empire and the history we had made throughout the day. I communicated our plan of action going forward, that we planned to sail at first light to rendezvous with SMS River Forth up the coast, where we would continue to patrol the local sea-lanes for as long as possible. I made my heartfelt admiration for the crew's outstanding conduct as clear as possible and to reinforce such a statement, I announced that a reward would be immediately provided. For so aptly discharging their duties, each man aboard was to be allotted a serving of captured rum from Algerine’s stores. The exhaustion temporarily drained from every man in sight as they broke into a cheer almost immediately, the first trio of cheers being in my name instead of the Kaiser as was typically navy custom. This was rectified soon after with a trio of applause for Leipzig and the Kaiser alike before the crew fell in for their well deserved drink and instructions going forward.

Before the nearby officers could return to their previous duties, Korvettenkapitän Kretschmar made a strange request to us all. He wished for the commissioned officers to meet below in Algerine’s wardroom at once, this confused me to no end as my executive officer would not explain the reasoning for such a congregation. Although truth be told there was some anger swelling inside me at the perceived insubordination, I was truly exhausted to the point where such semantics did not rate highly enough in my mind. Upon our arrival, Kretschmar produced a large bottle of whiskey apparently pilfered from the former cabin of Captain Corbett alongside an equally large smile of his own. I did feel rather childish after that, although I kept that fact to myself. With our civilian navigator Mr. Baumann joining us, we lined up glasses on the wardroom table and led into a cheer of our own. All in the room partook in the amber liquor so graciously supplied by our enemy and just for a moment, we collectively basked in the glory of victory. The exhaustion we all felt was temporarily stymied by the heat in our bellies and I was taken back to fond thoughts of my nearly 25 year long navy career before the war. This was it, a moment of glory that perhaps came once in a lifetime. While the moment itself was fleeting, it is a memory I will cherish for the remainder of my life. I did not realize at the time as each man filtered back out onto the deck to oversee their duties, it would be the last time I would see many of them alive.

For my own part, I entrusted oversight of the night's tasks to my executive officer and settled into a berth aboard Algerine for the evening. Kretschmar had assured me that he had been well rested previously and that I should prepare myself for the coming morning which I did not have any qualms with. The accommodations aboard the elderly British vessel was not exactly comfortable but I likely could have fallen asleep on my feet at such a point regardless. A sailor was eventually sent to wake me around 0415 that morning for a meeting with Mr. Baumann, in order for us to set a suitable course for when we departed. When I redressed and stepped back out onto the deck of Algerine, I was met with something I had not expected, the sound of familiar music met my ears. Some of the crew milling about their tasks between the vessels had stopped for a moment to look towards the direction of the sound. The ship's band was out near the bow playing a hauntingly beautiful rendition of 'Die Wacht am Rhein'. As I recognized the various instruments missing from the ensemble, a pang of sadness struck me from within. Even with over half of the band's usual members lost in the battle with Rainbow nearly a week prior, those who remained performed their duties admirably. It was a trait throughout the crew that I still have immense respect for to this day.

It was shortly after the band finished their performance when we all heard the commotion happening on the opposite side of Leipzig. Sailors were yelling to lower boats and something about men overboard, their voices were a harsh contrast from the sounds we were just privy to. As I crossed over the gangplanks to investigate what was happening, a great force yanked my feet out from under me as I tumbled to the deck. The accompanying shower of cold water down across the deck jarred me from the shock somewhat as my mind struggled for answers. It was soon clear though, our apparently helpless enemy had finally caught up with us.”

SMS Leipzig receiving repairs and paint touchups in a floating drydock located in Tsingtao during her service with the East Asia Squadron. An inserted portrait of Captain Haun can be seen in the top right corner.

Both torpedoes from Boat No.1’s salvo struck Leipzig along her starboard side at around 0430 hours that morning, the antique guncotton warheads causing considerable damage to the vessel. The first torpedo impacted almost directly below the third funnel, blowing the hull wide open and introducing a large amount of seawater into the surrounding boiler rooms. The second torpedo struck the cruiser roughly 30 to 40 feet further towards the stern in the machinery room, laying waste to the vessel's triple expansion engines and dynamo room in the process. While such catastrophic damage was certainly fatal in the long term, the state of the crew would only prove to hasten the ships sinking. Heavy casualties amongst the thinly stretched engineering department had effectively negated their ability to perform any kind of meaningful damage control, the situation being further complicated by the fact that the watertight doors in and surrounding the damaged compartments were not able to be completely closed in a timely manner following the attack. Lieutenant Rudolf Warner took control of a hastily organized team to survey the damage below and assist in damage control efforts however, the 20 degree starboard list and supplies freshly stripped from Algerine in anticipation of her scuttling proved a detriment to team as they attempted to navigate Leipzig’s passageways. Many of these men including Lieutenant Warner would ultimately give their lives in their attempt to save the ship, the flooding eventually overtaking their efforts and trapping many below decks.

By 0440, Captain Haun had organized a damage control party aboard Algerine with additional pumps and equipment; however before they could cross over to assist their crewmates, the sloop was forced to make steam and distance itself from the cruiser as her list dangerously accelerated. The ropes and gangplanks connecting both vessels together were severed in order to not pull the sloop down, making the attempted rescue parties efforts effectively in vain. Korvettenkapitän Kretschmar, still aboard Leipzig gave the order to begin abandoning ship as the vessel took on more water, partially then through the battle damage previously kept above the waterline. Algerine lowered and towed as many of its boats as possible as Leipzig’s sailors prepared to enter the water, many of their own boats unable to be launched due to a lack of power and the angle of the hull. Haun was faced with a difficult decision in the following moments, they had almost certainly been attacked by a submarine which still lurked nearby. Every minute he spent saving men from the water meant another potential torpedo launched in his direction. Thanks to the officers memoirs though, history is well aware that abandoning his man in hostile lands was a sacrifice that Haun was seemingly not willing to make. As Kretschmar had gathered all of the survivors on the ship's tilting bow, the German naval ensign was brought down, neatly folded and three cheers were given for the Leipzig. Before the men could take to the water though, the cruiser made a sudden lurch and began to fully capsize without warning. While some men would manage to escape relatively unscathed, many more were swept under or otherwise fatally wounded by the very ship they served aboard. By the time Algerine had raised sufficient steam and maneuvered herself back around to the debris field at 0450 hours, the cruisers keel was facing upwards towards the morning sky. German sailors made note after the fact of the jagged and warped hull of Leipzig as they swam towards the safety of Algerine and her nearby boats. Over the following 15 minutes, Algerine would pull 95 of Leipzig’s 191 man crew from the waters of Menzies Bay including Kretschmar and some other officers. As dawn had broken as rescue efforts dragged on, Haun did not wish to make himself any more of a target than was necessary and reluctantly left the area. All possible speed was made for Seymour Narrows to escape any submarines still lurking in the area and safely bypass Ripple Rock while the tide would remain slack.

An offset stern view of Algerine sailing around unknown coastal waters of British Columbia sometime throughout her Royal Navy service.

At approximately 0510 hours, Lieutenant Jones spotted the sloop approaching the narrows at top speed through the periscope of Boat No.2. Utilizing the insight of Mr. Johnson, the second Canadian boat had positioned itself off Wilfred Point with its pair of bow torpedo tubes pointed east towards the opposite shore. As only the eastern side of the passage was suitable to safely transit around Ripple Rock, the submarine was set to receive a perfect broadside target as the Germans passed. Jones would intermittently raise the periscope to confirm the approach of their target which was moving directly into their kill box. At a range of just over 500 yards, Boat No.2 fired its pair of torpedoes towards the passing sloop before retracting its periscope and counting down the half minute it would take for the weapons to reach their target. Lookouts aboard Algerine were none the wiser in regard to their silent stalker until a terrible explosion rocked the ship, shortly followed by a column of water raining down across the deck. To the astonishment of the onlooking Canadians, the German vessel emerged from the plume of water seemingly unharmed to continue its march unimpeded past Ripple Rock and northward up the coast. The first torpedo had deviated from its course and drifted ahead of the sloop, passing the vessel and exploding against the opposite shore. From the lack of a second explosion, the other torpedo was though to have missed as well. While Lieutenant Jones would attempt to turn the boat and bring his lone stern tube into action, his target was far outside of torpedo range once he had prepared a firing solution. Official Canadian reports would list both weapons as having missed their target; however, information surfaced following the end of the First World War which brought new light to the engagement.

Through official German Navy reports and interviews/memoirs of the crew aboard Algerine, it was confirmed that the second torpedo fired actually impacted the sloop near the first mast yet failed to detonate. One does not have to look far in period reports regarding the lackluster material condition of vintage torpedo stockpiles in both Esquimalt and Halifax to find a cause for such a failure. Haphazard transportation across the continent and a rushed inspection of the weapons prior to their use in combat are also potential trouble areas for mechanical reliability. Whatever the exact failure of the warhead in a situation such as this, the underfunded and overstretched Royal Canadian Navy had sadly become accustomed to such faulty equipment throughout their surface vessels and the newly procured submarines. Following the failed ambush of Algerine, Boat No.2 would surface and proceed back into Menzies Bay to attempt a rendezvous with her sister ship. A large amount of flotsam from the stricken cruiser had already begun to litter the surrounding waters to the point where it was drifting out towards the Seymour Narrows itself. The sight was reassuring news for Lieutenant Jones as even if part of the German flotilla had escaped, it would seem that their primary raider had been finally dealt with.

Correction with Regard to Names and Crew Sizes.

I was going to include this within the most recent chapter update however, I thought I would separate and threadmark this update in information to make sure it was not overlooked. Through my continued research on many of the ships involved in this timeline, I have found more accurate information in regard to Leipzig’s crew complement and the identity of many of its officers.

In regard to the crew complement, I had written the story under the assumption that Leipzig was at sea with a crew of 288 enlisted men and 14 officers totaling 302 overall. On closer inspection with new sources, Leipzig was listed to have a total crew of 333 sailors when she sank at the Battle of the Falkland Islands. Therefore I have gone back and adjusted the figures to better reflect reality. The updated numbers are not that far off from my original figures and overall do not affect the story in much of a meaningful way however, it was some overdue housekeeping that I felt had to be done. For anybody curious, the crew breakdowns for the three German ships just prior to the Raid on British Columbia are as follows.

Algerine - 80 crew

River Forth - 35 crew

Leipzig - 191 crew (27 men were killed or seriously injured in the engagement with Rainbow)

As it pertains to the identity of Leipzig’s officers, I had not been privy to their personal details until recently when I stumbled upon a very helpful memorial website for fallen WWI era German sailors. All of the German officers outside of Captain Haun had been fabricated by myself up until this point; however, I have now gone back and updated them to reflect their real world counterparts.

Lieutenant Ritter is replaced by Lieutenant Enno Kraus

Lieutenant Hartkopf is replaced by Korvettenkapitän Ulrich Kretschmar

I have done my best to retroactively edit chapters with this updated information; however, please bear with me as there may be some holdovers I need to correct. As always, thanks for reading and I hope you enjoy a long overdue and important chapter.

In regard to the crew complement, I had written the story under the assumption that Leipzig was at sea with a crew of 288 enlisted men and 14 officers totaling 302 overall. On closer inspection with new sources, Leipzig was listed to have a total crew of 333 sailors when she sank at the Battle of the Falkland Islands. Therefore I have gone back and adjusted the figures to better reflect reality. The updated numbers are not that far off from my original figures and overall do not affect the story in much of a meaningful way however, it was some overdue housekeeping that I felt had to be done. For anybody curious, the crew breakdowns for the three German ships just prior to the Raid on British Columbia are as follows.

Algerine - 80 crew

River Forth - 35 crew

Leipzig - 191 crew (27 men were killed or seriously injured in the engagement with Rainbow)

As it pertains to the identity of Leipzig’s officers, I had not been privy to their personal details until recently when I stumbled upon a very helpful memorial website for fallen WWI era German sailors. All of the German officers outside of Captain Haun had been fabricated by myself up until this point; however, I have now gone back and updated them to reflect their real world counterparts.

Lieutenant Ritter is replaced by Lieutenant Enno Kraus

Lieutenant Hartkopf is replaced by Korvettenkapitän Ulrich Kretschmar

I have done my best to retroactively edit chapters with this updated information; however, please bear with me as there may be some holdovers I need to correct. As always, thanks for reading and I hope you enjoy a long overdue and important chapter.

Thanks for the update

Actually on Vancouver Island at the moment and was struck by how tight the passages are for the ferry from the mainland. So many bays and coves that make so much more sense seeing in real life

Actually on Vancouver Island at the moment and was struck by how tight the passages are for the ferry from the mainland. So many bays and coves that make so much more sense seeing in real life

I hereby award Boat No.1, AKA "HMCS Unfit For Service", a battle star for actions against the cruiser Leipzig.

May she sink only when ordered to by her crew and only to the specified depth, may she rise up again on command from her officers, may she not suffer engine failure at inconvenient times, may she be sold for a reasonable scrap price at end of service.

Amen.

May she sink only when ordered to by her crew and only to the specified depth, may she rise up again on command from her officers, may she not suffer engine failure at inconvenient times, may she be sold for a reasonable scrap price at end of service.

Amen.

I quite enjoyed the touches from Captain Hauns writing talking about the celebrations after the fact, a very fitting reward for the Germans. Leipzig is gone now but the Germans still have two ships and a good number of men. Is there even anything remaining in the area to destroy?

Up Spirits!

Immediately following the attack on SMS Leipzig, Boat No.1 would suffer a series of defects which would put both the boat and her crew in serious peril. As the bow of the ship lightened significantly with the launch of two of her torpedoes, it would rapidly rise which in turn caused the crew to fight in order to level the vessel out. It is thought that crew overcorrection alongside a malfunction within the ballast system would result in the boat pressing herself into a nose dive towards the bottom of Menzies Bay. The same malfunction in the ballast would not permit the submarine to recover from her dive in time and even with her engines going into full astern and an order to vent the forward fuel tanks, the boat's bow would plow into the seabed. Reeling from the sudden impact in utter darkness and with water rushing in around them, the forward torpedo compartment, overseen by Sub-Lieutenant Maitland-Dougall sprang into action in an attempt to save their vessel. Closing the bulkhead doors leading back aft into the rest of the boat, the three young men sealed themselves inside what very well could have been a dark and increasingly watery coffin. They were initially forced to grasp blindly in the darkness, attempting to locate what damage the boat had suffered and what little equipment they had at their disposal to hold back the upcoming water.

As the lights flickered back to life and the situation was digested, the severity of their predicament became apparent. Deck plating in the compartment had been heaved upwards on the port side and water poured in from nearly every direction around both the deck and the warped forward bulkhead. The force of the impact had dislodged and bent the torpedo access hatches out of place, allowing even more water to ingress into the small compartment. By the time they had gathered themselves and reported the situation back to the Control Room, cold water began to lap over the toes of their sea boots. Nearby wooden cabinets and the torpedo reload stands were promptly broken down and wedged into place around the torpedo doors in an attempt to stop the flooding while uniform pieces were stuffed into leaking seams throughout the compartment. These quick but desperate actions were enough to stem the flooding for the minutes it took for the aft compartments to be surveyed and the impromptu damage control team to arrive on the scene. Due to the boats having been lightened of all unnecessary equipment prior to their sailing to improve their diving characteristics, the typical assortment of bracing timbers had been left ashore. The crew made do with whatever they could manage, descending upon the long wooden table in the ship's pantry and many of the folding bunks with their assortment of saws and hammers.

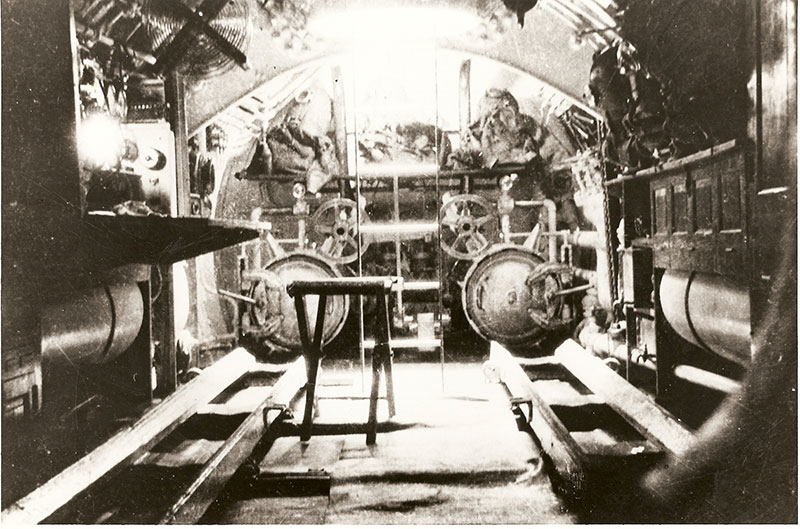

Torpedo compartment of Boat No.2, showcasing the wireless cabinet ready for use on the left and torpedo racks collapsed on the deck.

As the ship's crew worked to wedge more braces into the warped compartment and hammer the torpedo doors shut, members of the engineering team put the portable pumps to work. The small machines held the inflow at bay but until the leaks could be sufficiently plugged, little progress could be made to bring the boat truly out of harm's way. While the men forward worked to save the boat, their comrades within the control room amidships continued to adjust the trim of the boat as weight shifted throughout the hull. Lieutenant Keyes would have normally wished to surface his boat immediately in such a situation to lessen the pressure on the damaged hull but considering the temperamental nature of their ballast system and the fact that his periscope had been jammed due to the impact, attempting to surface could very much put them in the gunsights of a waiting enemy or could lead to another uncontrollable change in depth. Over an excruciating twenty minutes, leaks in the torpedo compartment would be reduced to the point where the portable pumps would begin to make worthwhile progress and some crew members could return to their previous stations. A survey would be done with regard to damage throughout the vessel and while most outside the torpedo room was not immediately threatening to their survival, the boat was no longer combat effective. Various gauges within the control room were cracked, the periscope was jammed, the wireless station had been ruined by water, trim controls forward were sluggish and the forward hydroplane controls seemed to be completely unresponsive.

With the situation coming largely under control in the coming minutes, Lieutenant Keyes ordered testing of the ship's ballast system in anticipation of surfacing. Compressed air could be heard normally entering the aft and amidships main tanks but when the forward tank was attempted to be emptied, yells from the torpedo compartment caused the process to be immediately halted. High pressure air could be heard loudly venting below the deck, meaning that the bow ballast tank was open to the sea. The recently emptied bow fuel tanks remained the only source of lift in that section of the boat, meaning that Keyes would have to be resourceful in order to successfully bring his boat from the depths. Over the sounds of the pumps forward and the motors aft, the men listened to the sound of propellers swirling above. If they could not fully control their ability to surface, they would have to wait until their potential enemy above had departed. At roughly 0505, the distinctive sound of the nearby vessel's propulsion began to fade to a point where it soon became indistinguishable from the boat's natural din. Similarly to his attempt to stop the boats out of control dive earlier, Keyes would order the electric motors into full astern as the tanks were blown. Working in tandem with the mercifully compliant amidships and rear ballast tanks, the screws hauled the submarine towards the surface stern first as her crew held on amidst creaking of the hull. As the few functioning gauges indicated they were approaching the surface, the men within the control room fought with the hydroplane controls in an attempt to level the boat out to some extent. This would prove to be a fairly difficult feat in hindsight considering that the boat had lost her forward hydroplanes and lacked much of her normal buoyancy forward, although the thick arms of the sailors eventually wrenched the controls into compliance. Lieutenant Keyes would hand over the helm to a battered but still capable Sub-Lieutenant Maitland-Dougall as the boat rolled in the surf, climbing up towards the conning tower with a lookout on his heels. A quick glance out of the towers internal view ports showed nothing and the fact they were not being fired was a positive development, Keyes would crack the main hatch and once the pressure had subsided, he clambered back into the light above. No time was wasted in scanning their immediate surroundings which revealed that they had surfaced directly into a sea of various flotsam and debris, emanating from the remains of the Leipzig which lay keel up a few hundred yards off their port side.

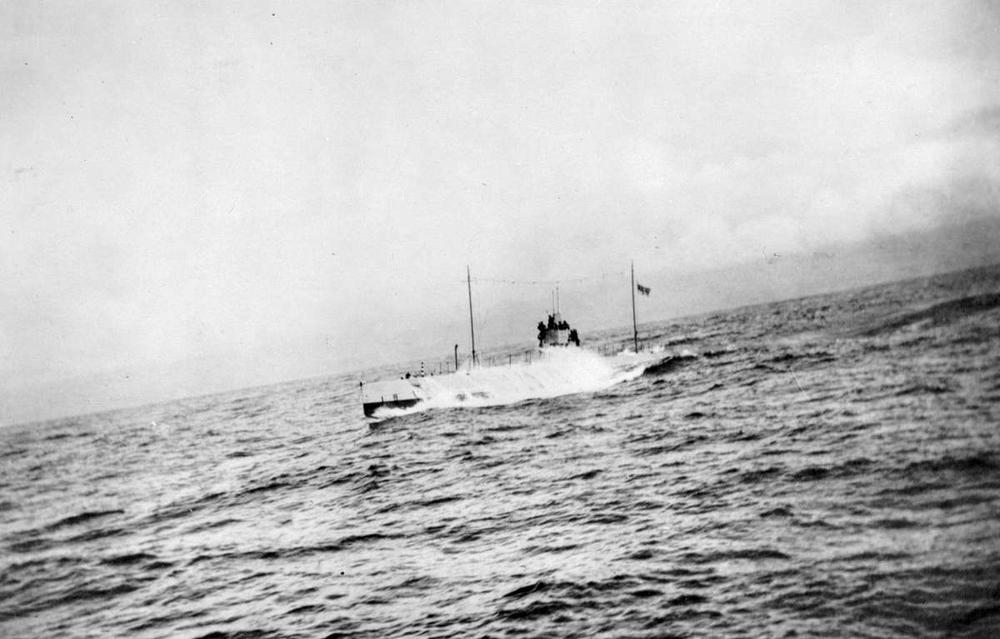

A view from a nearby vessel of Boat No.2 surfacing or rolling in the surf.

Being aboard Boat No.1 at the time, Able Seaman Frederick Crickard would give the following description in a 1949 interview with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

“Once it was clear that we’d surfaced and seemingly survived our ordeal, many of the men throughout the ship were chomping at the bit for any news about the success or failure of our attack. It was a tense few minutes waiting for the boys to scan the surrounding waters but when word came down through the conning tower hatch that Leipzig lay before us with her belly facing upwards, a thunderous chorus erupted throughout the sub. We had paid back the Hun who had so recently blown through many of our towns, many of the local lads nearly broke into tears when they heard. So much had happened in so little time, we had barely been in these boats for a few weeks and we had put the sword to one of the Kaisers finest. At the time we thought there could be no greater music to our ears but we were swiftly proved wrong when a second order came down the hatch. Lieutenant Keyes announced the one phrase that any man serving within the Navy adores so highly, ‘up spirits!’ The coxswain wasted little time clambering through the boat's compartments with a bottle of rum in hand as each man ran for their tots. Some greedily gulped down the contents nearly as soon as they got them while others gave a quick toast before indulging. Even some of the younger lads and the ship's officers who would usually be excluded from the ration found themselves partaking in the spirits.”

Once it was clear that they were the lone functional warship in the bay, Keyes moved to more closely inspect the damage his vessel had taken in their recent escapade. When the officer clambered down the conning tower and eventually reached the partially submerged bow of the boat, the true extent of their peril was evident. The port side hydroplane was completely missing while its opposite on the starboard side was crumpled into uselessness, the bottom port section of the bow looked as if one took a lit cigarette and butted it out onto the ground. Between the swells of the surf, the sides of the vessel roughly around where the forward ballast and trim tanks were located was surrounded by a tangled mess of dented scrap. Most worryingly of all, the boat's heavy circular bow caps had been jammed to the starboard and barely remained attached to the hull by a few strands of steel. The exposed muzzles of the boat's starboard pair of torpedo tubes could be clearly seen, likely causing Keyes a considerable amount of anxiety. Without ability to remove the torpedoes from the tubes and without the bow cap to protect the warheads, the antique firing pistols would be subject to waves constantly pounding them if they proceeded at any kind of speed. There was little that could be done to remedy the situation, Keyes would have to carefully pilot his boat and pray that the inbuilt safety mechanisms in the warheads kept their 200lbs of explosive filler docile, if the end would come thankfully it would likely be instant for all aboard. Soon after the rest of the crew was informed with regard to the extent of the damage (with the exposed warhead fact conveniently passed over as not to worry the men), an explosion was clearly heard emanating from the Seymour Narrows. As they were in no state to venture out into the Narrows and join their sister ship in what they guessed was a fight, Boat No.1 moved through the local debris field in search of survivors. The fact that the submarine lacked even a single rowboat to retrieve men adrift would have complicated rescue efforts but as they searched, nothing but an increasing count of bodies would be found. Keyes would bring the boat closer in order to view what remained of Leipzig. Perhaps five or ten feet of her barnacle-covered keel remained above the water, the warped hull plating along her side more than told the story of the morning's events.

While Keyes would be correct in assuming a high number of casualties from the sinking due to a lack of survivors, Captain Haun had effectively combed the waters clean of any men still able to be saved minutes before. After firing the majority of its weapons in its unsuccessful attack on Algerine, Boat No.2 would eventually make its way back into the bay in search of her sister. With Boat No.1 lacking a functional wireless set, neither knew the status of the other until visual contact was established at 0525 hours, the pair tying up alongside each other soon after to discuss their situation. Although one of the raiders had escaped in the end, the boats had succeeded in their mission to destroy the Germans main and most effective combatant found on this side of the Pacific. Tying the enemy to an antiquated sloop and a single support ship would drastically decrease the potency of their enemy to effectively strike worthwhile targets, although both submarines would be unable to sortie North or out into the Pacific to continue their hunt. Any future engagements would have to be fought by British and Japanese warships, if the Germans proved foolish enough to remain off the coast until they arrived.

As the lights flickered back to life and the situation was digested, the severity of their predicament became apparent. Deck plating in the compartment had been heaved upwards on the port side and water poured in from nearly every direction around both the deck and the warped forward bulkhead. The force of the impact had dislodged and bent the torpedo access hatches out of place, allowing even more water to ingress into the small compartment. By the time they had gathered themselves and reported the situation back to the Control Room, cold water began to lap over the toes of their sea boots. Nearby wooden cabinets and the torpedo reload stands were promptly broken down and wedged into place around the torpedo doors in an attempt to stop the flooding while uniform pieces were stuffed into leaking seams throughout the compartment. These quick but desperate actions were enough to stem the flooding for the minutes it took for the aft compartments to be surveyed and the impromptu damage control team to arrive on the scene. Due to the boats having been lightened of all unnecessary equipment prior to their sailing to improve their diving characteristics, the typical assortment of bracing timbers had been left ashore. The crew made do with whatever they could manage, descending upon the long wooden table in the ship's pantry and many of the folding bunks with their assortment of saws and hammers.

Torpedo compartment of Boat No.2, showcasing the wireless cabinet ready for use on the left and torpedo racks collapsed on the deck.

As the ship's crew worked to wedge more braces into the warped compartment and hammer the torpedo doors shut, members of the engineering team put the portable pumps to work. The small machines held the inflow at bay but until the leaks could be sufficiently plugged, little progress could be made to bring the boat truly out of harm's way. While the men forward worked to save the boat, their comrades within the control room amidships continued to adjust the trim of the boat as weight shifted throughout the hull. Lieutenant Keyes would have normally wished to surface his boat immediately in such a situation to lessen the pressure on the damaged hull but considering the temperamental nature of their ballast system and the fact that his periscope had been jammed due to the impact, attempting to surface could very much put them in the gunsights of a waiting enemy or could lead to another uncontrollable change in depth. Over an excruciating twenty minutes, leaks in the torpedo compartment would be reduced to the point where the portable pumps would begin to make worthwhile progress and some crew members could return to their previous stations. A survey would be done with regard to damage throughout the vessel and while most outside the torpedo room was not immediately threatening to their survival, the boat was no longer combat effective. Various gauges within the control room were cracked, the periscope was jammed, the wireless station had been ruined by water, trim controls forward were sluggish and the forward hydroplane controls seemed to be completely unresponsive.

With the situation coming largely under control in the coming minutes, Lieutenant Keyes ordered testing of the ship's ballast system in anticipation of surfacing. Compressed air could be heard normally entering the aft and amidships main tanks but when the forward tank was attempted to be emptied, yells from the torpedo compartment caused the process to be immediately halted. High pressure air could be heard loudly venting below the deck, meaning that the bow ballast tank was open to the sea. The recently emptied bow fuel tanks remained the only source of lift in that section of the boat, meaning that Keyes would have to be resourceful in order to successfully bring his boat from the depths. Over the sounds of the pumps forward and the motors aft, the men listened to the sound of propellers swirling above. If they could not fully control their ability to surface, they would have to wait until their potential enemy above had departed. At roughly 0505, the distinctive sound of the nearby vessel's propulsion began to fade to a point where it soon became indistinguishable from the boat's natural din. Similarly to his attempt to stop the boats out of control dive earlier, Keyes would order the electric motors into full astern as the tanks were blown. Working in tandem with the mercifully compliant amidships and rear ballast tanks, the screws hauled the submarine towards the surface stern first as her crew held on amidst creaking of the hull. As the few functioning gauges indicated they were approaching the surface, the men within the control room fought with the hydroplane controls in an attempt to level the boat out to some extent. This would prove to be a fairly difficult feat in hindsight considering that the boat had lost her forward hydroplanes and lacked much of her normal buoyancy forward, although the thick arms of the sailors eventually wrenched the controls into compliance. Lieutenant Keyes would hand over the helm to a battered but still capable Sub-Lieutenant Maitland-Dougall as the boat rolled in the surf, climbing up towards the conning tower with a lookout on his heels. A quick glance out of the towers internal view ports showed nothing and the fact they were not being fired was a positive development, Keyes would crack the main hatch and once the pressure had subsided, he clambered back into the light above. No time was wasted in scanning their immediate surroundings which revealed that they had surfaced directly into a sea of various flotsam and debris, emanating from the remains of the Leipzig which lay keel up a few hundred yards off their port side.

A view from a nearby vessel of Boat No.2 surfacing or rolling in the surf.

Being aboard Boat No.1 at the time, Able Seaman Frederick Crickard would give the following description in a 1949 interview with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

“Once it was clear that we’d surfaced and seemingly survived our ordeal, many of the men throughout the ship were chomping at the bit for any news about the success or failure of our attack. It was a tense few minutes waiting for the boys to scan the surrounding waters but when word came down through the conning tower hatch that Leipzig lay before us with her belly facing upwards, a thunderous chorus erupted throughout the sub. We had paid back the Hun who had so recently blown through many of our towns, many of the local lads nearly broke into tears when they heard. So much had happened in so little time, we had barely been in these boats for a few weeks and we had put the sword to one of the Kaisers finest. At the time we thought there could be no greater music to our ears but we were swiftly proved wrong when a second order came down the hatch. Lieutenant Keyes announced the one phrase that any man serving within the Navy adores so highly, ‘up spirits!’ The coxswain wasted little time clambering through the boat's compartments with a bottle of rum in hand as each man ran for their tots. Some greedily gulped down the contents nearly as soon as they got them while others gave a quick toast before indulging. Even some of the younger lads and the ship's officers who would usually be excluded from the ration found themselves partaking in the spirits.”

Once it was clear that they were the lone functional warship in the bay, Keyes moved to more closely inspect the damage his vessel had taken in their recent escapade. When the officer clambered down the conning tower and eventually reached the partially submerged bow of the boat, the true extent of their peril was evident. The port side hydroplane was completely missing while its opposite on the starboard side was crumpled into uselessness, the bottom port section of the bow looked as if one took a lit cigarette and butted it out onto the ground. Between the swells of the surf, the sides of the vessel roughly around where the forward ballast and trim tanks were located was surrounded by a tangled mess of dented scrap. Most worryingly of all, the boat's heavy circular bow caps had been jammed to the starboard and barely remained attached to the hull by a few strands of steel. The exposed muzzles of the boat's starboard pair of torpedo tubes could be clearly seen, likely causing Keyes a considerable amount of anxiety. Without ability to remove the torpedoes from the tubes and without the bow cap to protect the warheads, the antique firing pistols would be subject to waves constantly pounding them if they proceeded at any kind of speed. There was little that could be done to remedy the situation, Keyes would have to carefully pilot his boat and pray that the inbuilt safety mechanisms in the warheads kept their 200lbs of explosive filler docile, if the end would come thankfully it would likely be instant for all aboard. Soon after the rest of the crew was informed with regard to the extent of the damage (with the exposed warhead fact conveniently passed over as not to worry the men), an explosion was clearly heard emanating from the Seymour Narrows. As they were in no state to venture out into the Narrows and join their sister ship in what they guessed was a fight, Boat No.1 moved through the local debris field in search of survivors. The fact that the submarine lacked even a single rowboat to retrieve men adrift would have complicated rescue efforts but as they searched, nothing but an increasing count of bodies would be found. Keyes would bring the boat closer in order to view what remained of Leipzig. Perhaps five or ten feet of her barnacle-covered keel remained above the water, the warped hull plating along her side more than told the story of the morning's events.

While Keyes would be correct in assuming a high number of casualties from the sinking due to a lack of survivors, Captain Haun had effectively combed the waters clean of any men still able to be saved minutes before. After firing the majority of its weapons in its unsuccessful attack on Algerine, Boat No.2 would eventually make its way back into the bay in search of her sister. With Boat No.1 lacking a functional wireless set, neither knew the status of the other until visual contact was established at 0525 hours, the pair tying up alongside each other soon after to discuss their situation. Although one of the raiders had escaped in the end, the boats had succeeded in their mission to destroy the Germans main and most effective combatant found on this side of the Pacific. Tying the enemy to an antiquated sloop and a single support ship would drastically decrease the potency of their enemy to effectively strike worthwhile targets, although both submarines would be unable to sortie North or out into the Pacific to continue their hunt. Any future engagements would have to be fought by British and Japanese warships, if the Germans proved foolish enough to remain off the coast until they arrived.

Both sides manage to escape by the skin of their teeth but end up crippled by the encounter. I guess this is finally the end of the German rampage.

Pit Stop

With both Canadian submarines tied up alongside one another in Menzies Bay, their officers were almost immediately faced with a dilemma. They had been so desperate to catch up with the Germans that much like a dog which had finally caught its tail, they were at a loss for how to proceed. Over a half hour of transmitting messages regarding their situation via Boat No.2’s wireless set would bring back no response, the destruction of the Cape Lazo Wireless Station would mean that their short ranged set was largely useless. Lacking the ability to gain outside support from their current location, the pair were effectively on their own in the expansive waterways of British Columbia. Boat No.2 had the fuel margins to safely transit back to Esquimalt herself if required but her sister was in a far worse state. The desperate action of blowing the forward fuel tanks to surface likely saved the boat but had also deprived her of a significant amount of fuel. Even if the fuel supply turned out to be sufficient to return to a major port, her material condition made the idea of sailing the vessel any reasonable distance a very risky proposal. Running at any kind of speed could have reopened leaks in the crumpled forward bulkhead at best or at worst, detonated the antique torpedo warheads jammed inside their tubes. That was assuming the weather would be cooperative, any change could further dampen the survival of the boat and her crew. Abandoning Boat No.1 in Menzies Bay and taking the crew aboard her sister ship for their retreat was considered but as it could result in the complete loss of the unattended boat alongside being a very poor way to end an operation, Keyes had a difficult choice to make. It is likely that Keyes wished to give the men some say in the matter and would eventually inform them about the true danger they faced. The crew had performed admirably but they were still inexperienced and were rather worn from the events of the past few days, more mistakes would be expected if they were pushed. Accounts from the men show that immediately after, he presented them with a choice. Any man who did not wish to stay aboard for their return trip could transfer to Boat No.2, only a volunteer skeleton crew would be retained aboard Boat No.1 to keep the boat operational and minimize potential casualties. In an almost identical manner to how they were initially recruited, not a single man would take up the offer, all choosing to stay aboard their boat.

One sailor would famously state, “The only way I’ll be stepping foot off this boat is in port.”

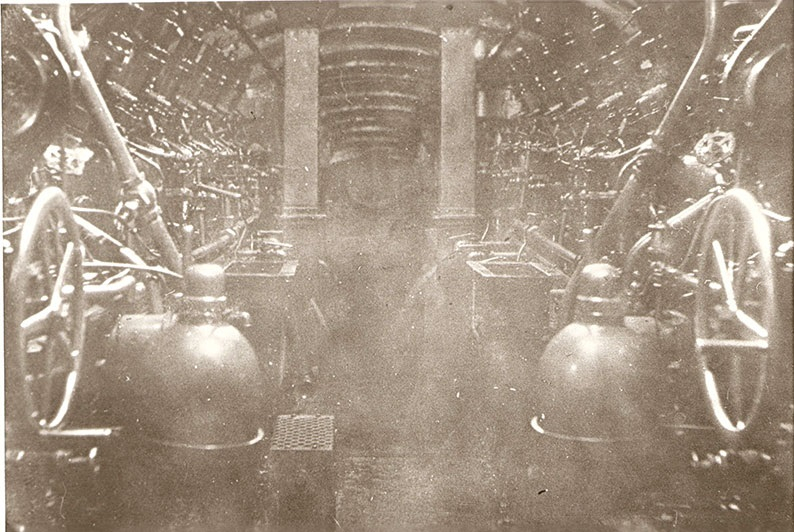

Engine room of one of the Canadian submarines, a decidedly uncomfortable, cramped and dirty affair but vital nonetheless.

It would eventually be decided to transfer all of Boat No.2’s pumps and damage control equipment to her damaged sister in case her condition worsened on the journey. Comox would be chosen as the most feasible destination considering it sat only 40 miles away, half the distance to Nanaimo and just below a quarter of the distance to Esquimalt. The aforementioned port was seen as a step too far considering Boat No.1’s condition and one can surmise that Lieutenant Keyes did not want the vessel at sea for a minute longer than was required. Although the nearby Union Bay had been attacked by the Germans, it was unlikely that the small town had been worth their bombardment given its lack of infrastructure. Even if Comox turned out to be damaged, its bay would serve as a suitable anchorage for Boat No.1 and would allow her crew proper respite. More importantly, the town would have a connection to the local telegram network. Shortly after 0610, both boats would depart Menzies Bay as the upturned hull of Leipzig finished her descent to the sea floor. Boat No.1 would lead with her sister close behind, ready to come alongside and take men off if required. In a test of both fate and the forward bulkhead, the engineers slowly throttled up the diesels until the vessel reached a cruising speed of 7 knots. Leaks had increased forward but constant reinforcement of the bulkhead and additional pumps under the watchful eye of Sub-Lieutenant Maitland-Dougall kept up with the flooding. The journey back down the coast would be wrought with further stress placed upon the ragged crew, the situation not helped by a breakfast described as dry bully beef sandwiches washed down by strange tasting water from the boats freshwater tanks. Pushing the unreliable diesels to the edge of their capability the night previously had resulted in a bevy of issues for the engineering staff to contend with, bearings had begun to show signs of overheating and the main shaft had visible warpage along its length. Crew stationed closer aft would report an increasing amount of vibration as they made their way closer to Comox. A loss of power outside of port would almost certainly spell doom for the boat itself if not her crew as well so as best could be done, the men aft kept her on course. The wear and damage would require major repairs in the long term but as long as port was reached, she could always be towed home at a later date.

Town of Comox around 1914 as viewed from the main pier, a relatively sparse but developing area.

In the end, Boat No.1 would manage to hold herself together and reach the entrance of Comox harbor shortly after 1200 hours, the flattened remains of the Cape Lazo Wireless visible as she passed. Both vessels would enter the small harbor with their White Ensigns flying, Boat No.1 remained anchored off shore as to not bring two primed torpedoes to the town's only pier. After tying up his boat alongside, Lieutenant Jones would head into town with a posse of sailors following closely behind. The men were to organize transportation ashore for the crew of Boat No.1 while Jones would attempt to establish communication with Esquimalt. Due to the recent bombardment and the spreading fires from Union Bay, the people of Comox had not received their daily mail shipment and were rather on edge. The destruction of the rail system down the coast by Algerine had severed the town physically from the outside world, leaving landline connections and old buggy roads as their only means of contact. More than happy to see vessels of the Navy in their little town, citizens flocked to the streets to greet the sailors as more arrived. When it was made clear that the men would likely be in town for sometime, the owner of the local hotel went to work preparing space for the tired sailors as they were shipped ashore piecemeal by local craft. Much to the chagrin of the Canadians, communication outside of the town had been incredibly spotty at best, nonfunctional at worst. The raging forest fires down the coast had begun to damage much of the area's nascent telephone and telegram infrastructure, leaving operators either unable to reliably receive and transmit messages. After nearly an hour of nonstop attempts, one of the local operators received a response from their counterpart in Port Alberni, 28 miles to the South. Being downwind from the ongoing blaze had spared some of the lines and mercifully allowed the message to be passed on. It read as follows:

URGENT URGENT TO HMCD ESQUIMALT. SUBMARINES SUNK CRUISER LEIPZIG OFF SEYMOUR NARROWS 0430 HOURS THIS MORNING. ALGERINE ESCAPED NORTH. BOAT ONE HEAVILY DAMAGED AND SHELTERING IN COMOX. NO CASUALTIES. REQUIRE TUG AND TRANSPORT AT ONCE.

The message had been kept brief to speed up repeated dispatch attempts and give the best chance of getting through. With the currently worsening condition of the local telegram network, receiving a prompt response from Esquimalt was seen as unlikely by all parties. Therefore until they were notified of their next action, the crew of both boats had more earned some rest. A small crew would rotate from ship to shore in order to maintain the damaged submarines pumps but otherwise, the men were largely ashore. Once word had spread throughout the town of their deeds however, any chance at immediate rest would be quickly replaced by a heroes welcome.

One sailor would famously state, “The only way I’ll be stepping foot off this boat is in port.”

Engine room of one of the Canadian submarines, a decidedly uncomfortable, cramped and dirty affair but vital nonetheless.

It would eventually be decided to transfer all of Boat No.2’s pumps and damage control equipment to her damaged sister in case her condition worsened on the journey. Comox would be chosen as the most feasible destination considering it sat only 40 miles away, half the distance to Nanaimo and just below a quarter of the distance to Esquimalt. The aforementioned port was seen as a step too far considering Boat No.1’s condition and one can surmise that Lieutenant Keyes did not want the vessel at sea for a minute longer than was required. Although the nearby Union Bay had been attacked by the Germans, it was unlikely that the small town had been worth their bombardment given its lack of infrastructure. Even if Comox turned out to be damaged, its bay would serve as a suitable anchorage for Boat No.1 and would allow her crew proper respite. More importantly, the town would have a connection to the local telegram network. Shortly after 0610, both boats would depart Menzies Bay as the upturned hull of Leipzig finished her descent to the sea floor. Boat No.1 would lead with her sister close behind, ready to come alongside and take men off if required. In a test of both fate and the forward bulkhead, the engineers slowly throttled up the diesels until the vessel reached a cruising speed of 7 knots. Leaks had increased forward but constant reinforcement of the bulkhead and additional pumps under the watchful eye of Sub-Lieutenant Maitland-Dougall kept up with the flooding. The journey back down the coast would be wrought with further stress placed upon the ragged crew, the situation not helped by a breakfast described as dry bully beef sandwiches washed down by strange tasting water from the boats freshwater tanks. Pushing the unreliable diesels to the edge of their capability the night previously had resulted in a bevy of issues for the engineering staff to contend with, bearings had begun to show signs of overheating and the main shaft had visible warpage along its length. Crew stationed closer aft would report an increasing amount of vibration as they made their way closer to Comox. A loss of power outside of port would almost certainly spell doom for the boat itself if not her crew as well so as best could be done, the men aft kept her on course. The wear and damage would require major repairs in the long term but as long as port was reached, she could always be towed home at a later date.

Town of Comox around 1914 as viewed from the main pier, a relatively sparse but developing area.

In the end, Boat No.1 would manage to hold herself together and reach the entrance of Comox harbor shortly after 1200 hours, the flattened remains of the Cape Lazo Wireless visible as she passed. Both vessels would enter the small harbor with their White Ensigns flying, Boat No.1 remained anchored off shore as to not bring two primed torpedoes to the town's only pier. After tying up his boat alongside, Lieutenant Jones would head into town with a posse of sailors following closely behind. The men were to organize transportation ashore for the crew of Boat No.1 while Jones would attempt to establish communication with Esquimalt. Due to the recent bombardment and the spreading fires from Union Bay, the people of Comox had not received their daily mail shipment and were rather on edge. The destruction of the rail system down the coast by Algerine had severed the town physically from the outside world, leaving landline connections and old buggy roads as their only means of contact. More than happy to see vessels of the Navy in their little town, citizens flocked to the streets to greet the sailors as more arrived. When it was made clear that the men would likely be in town for sometime, the owner of the local hotel went to work preparing space for the tired sailors as they were shipped ashore piecemeal by local craft. Much to the chagrin of the Canadians, communication outside of the town had been incredibly spotty at best, nonfunctional at worst. The raging forest fires down the coast had begun to damage much of the area's nascent telephone and telegram infrastructure, leaving operators either unable to reliably receive and transmit messages. After nearly an hour of nonstop attempts, one of the local operators received a response from their counterpart in Port Alberni, 28 miles to the South. Being downwind from the ongoing blaze had spared some of the lines and mercifully allowed the message to be passed on. It read as follows:

URGENT URGENT TO HMCD ESQUIMALT. SUBMARINES SUNK CRUISER LEIPZIG OFF SEYMOUR NARROWS 0430 HOURS THIS MORNING. ALGERINE ESCAPED NORTH. BOAT ONE HEAVILY DAMAGED AND SHELTERING IN COMOX. NO CASUALTIES. REQUIRE TUG AND TRANSPORT AT ONCE.

The message had been kept brief to speed up repeated dispatch attempts and give the best chance of getting through. With the currently worsening condition of the local telegram network, receiving a prompt response from Esquimalt was seen as unlikely by all parties. Therefore until they were notified of their next action, the crew of both boats had more earned some rest. A small crew would rotate from ship to shore in order to maintain the damaged submarines pumps but otherwise, the men were largely ashore. Once word had spread throughout the town of their deeds however, any chance at immediate rest would be quickly replaced by a heroes welcome.

Last edited:

NEW WIRELESS WHO DIS? - the memeified response from Esquimalt

Seriously though, those boys are going to be exhausted by the time this is over (and probably very hung over to boot, beginning a fine Navy Tradition, I'm sure)

Seriously though, those boys are going to be exhausted by the time this is over (and probably very hung over to boot, beginning a fine Navy Tradition, I'm sure)

Shouldn't that be 'upwind'? Downwind implies the fire's heading that way as it's blown.Being downwind from the ongoing blaze had spared some of the lines and mercifully allowed the message to be passed on.

Last edited:

The sailors have earned the rest for sure. It’s not like they can keep going after the Germans, the fact that they got a chance to attack them with those subs in the first place is a miracle.

A coastal forest fire would mess with communications. Telegraph and telephone, where it existed, tended to run beside the rail lines on poles. So if the fire ran over the rail line, the telegraph would go. I expect the telegraph would be cut in multiple places after Leipzig and Algerine’s rampaging.

The nearest Dominion wireless station to Seymour Narrows at the time was at Alert Bay, more than 100 miles away with many mountains intervening, and not to my knowledge connected to a land telegraph. So it would have a hard time receiving from the subs.

The nearest Dominion wireless station to Seymour Narrows at the time was at Alert Bay, more than 100 miles away with many mountains intervening, and not to my knowledge connected to a land telegraph. So it would have a hard time receiving from the subs.

Indeed, I had to look at period resources to try and piece together what settlements and towns were actually connected via telegram/telephone. Those same period sources complain about interruptions in service due to the poor quality of service poles holding up the lines, any serious amount of wind or weather could cause outages. Add artillery shells and fire into the mix and the outcome is unsurprising.A coastal forest fire would mess with communications. Telegraph and telephone, where it existed, tended to run beside the rail lines on poles. So if the fire ran over the rail line, the telegraph would go. I expect the telegraph would be cut in multiple places after Leipzig and Algerine’s rampaging.

The nearest Dominion wireless station to Seymour Narrows at the time was at Alert Bay, more than 100 miles away with many mountains intervening, and not to my knowledge connected to a land telegraph. So it would have a hard time receiving from the subs.