After Confederate hopes of victory died in the quiet green hills of Union Mills, the eventual triumph of the Union seemed assured. Indeed, with all three main Southern armies on the retreat and the Union in control of the Mississippi, its own armies poised to strike at the vitals of the Confederacy, few doubted that the end of the war was in sight. “Peace does not appear so distant as it did”, Lincoln wrote in the fall of 1863. “I hope it will come soon, and come to stay; and so come as to be worth the keeping in all future time.” But whether that peace was worth keeping would depend largely on what form it took. The prospect of Northern victory opened many questions regarding the future of the United States, of how the government would deal with the rebel states and what place African Americans would occupy in the post-slavery South. “How will their freedom affect us?”, asked a Northern pamphleteer, as he pondered the great changes that war and emancipation would bring to the United States, a question that reflected the complex interrogatives that Reconstruction raised.

Reconstruction, defined as the process by which the Union government would administer occupied territories during the war and reintegrate them into the Union after it, “began shortly after the fall of Washington”. Indeed, as the Union Army advanced into the South, it had to grapple with questions regarding how the liberated territories were to be ruled, what their relations to the National government were, and how to deal with their inhabitants, both Black and White. During the first year of the war, the Union’s leaders were more preoccupied with whether they could win the war at all, and most of their anti-slavery measures were tentative, certainly not enough to effectuate a complete revolution in the Southern states. Then, the Emancipation Proclamation forever closed the possibility of the war resulting in the Union as it was. It established that from the flames of war a society free of slavery would emerge. But in doing so, the Proclamation also “unleashed a dynamic debate over the meaning of American freedom and the definition and entitlements of American citizenship”.

The question of Reconstruction reached into all the aspects of American life, in both North and South. The “peculiar institution” was not a mere aspect of the South, but the cornerstone of its economy and the basis of its social and political system. Slavery created a socio-political system that deposited most power in the hands of the planter elite, which in turn used its political and social influence to maintain and expand slavery. Even outside of the South, the “Slave Power” had profoundly influenced American life, contributing to the North’s industrialization, creating deep prejudices against Black Americans in Yankees, and maintaining a national political system that gave undue influence to pro-slavery Southerners. Slavery was not incidental to the war, but rather caused it directly, for the rise of the Republican Party and the election of Abraham Lincoln represented a threat to this influence and consequently to slavery itself. The end of slavery was then sure to bring revolutionary changes, not just to labor relations in the South, but to the entire economic, political, cultural and social fabric of the entire United States.

Reconstructing the South thus entailed more than simply outlawing slavery and declaring Black people free. At least, that was the conviction held by most Republicans. The painful experience of war had taught them “that the pieces of the old Union could not be cobbled together”. Slavery, it was agreed, was at an end; the prominent role the architects of secession had played in national politics was over as well. But Radicals and Moderates disagreed on the

substance of reconstruction, that is, how far the process would go, which people would take control in the post-war regime, and what role Black people would play in the political and social life of this new South. Likewise, there were disagreements over how Reconstruction would work in practical terms, meaning how the former Confederacy would be reintegrated into the Union, under which and whose terms. Behind all these concerns, the overreaching interrogative was how slavery’s end would redefine American freedom. Debate over the meaning of freedom, the definition of citizenship and the very nature of the Federal government and its relation to the states started like never before since the nation’s founding, as Republicans grappled with these complex questions.

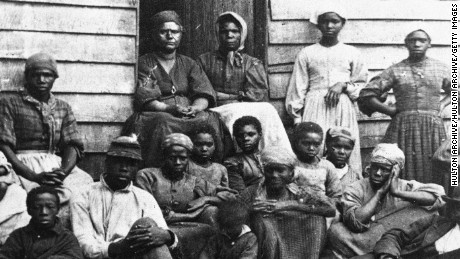

The question of Reconstruction increasingly came to be associated with the future of the freedmen

By the end of 1863, all Republicans agreed that slavery had to be abolished, and that Black people would be forever free. But

how slavery was to be destroyed was a practical question that still troubled Republicans more than a year after the Emancipation Proclamation. Hundreds of thousands of slaves had already been freed by the Union Army, but military emancipation proved to be an imperfect instrument for the liberation of millions. The Confederacy was “by far the largest slave society in the world, possibly the largest in the history of the world”, with over four million slaves, twice the number of Brazil or even Rome at its height. Three years of bloody campaigning had pushed the Confederates to the brink, but large sections of its enormous expanse remained untouched by the hard hand of war, the Black people there still enslaved. Around 15% of the South’s slaves had been freed by the Army by 1864. Though this was a significant number, the great majority of slaves remained on the plantation, be it because they couldn’t reach the Yankees or due to Confederate threats and violence.

Furthermore, though Republicans believed and decreed that liberated slaves would be “forever free”, the Proclamation by itself could not assure that their freedom would be indeed enduring. Once the fighting stopped the freedmen would be under risk of violence or even re-enslavement, and even though the Union had decided that it had a responsibility to protect them from these threats, how this protection was to be effectuated had to still be decided. Within this context, military emancipation proved woefully inadequate. As James Oakes puts it, military emancipation “was brutal. It would not free all the slaves. And it might not free any of them forever”. The Three Bureaus, of Land, Freedmen, and Labor, had been created to address this problem and offer protection and guidance to the freedmen on their transition from slavery to freedom. But they were conceived as temporary solutions. Black people’s freedom could only be rendered lasting and meaningful by a successful Reconstruction, a process that necessarily required a firmer legal and practical basis given through Federal action.

The Third Confiscation Act had seemingly settled the issue by disposing that the land confiscated from traitors would be given to the loyal freedmen, thus creating a Black yeomanry that would enjoy economic independence and equal opportunities for advancement. But the practical social and economic consequences of land redistribution were nothing less than revolutionary. Slavery, it must be emphasized, was “first and foremost, a system of labor”. Its end “opens a vast and most difficult subject”, the

New York Times admitted, for the organization of land and labor in the post-war South would be the basis of its politics, economics and society, just as slavery had been in the ante-bellum. “Will the Negro work?”, was the “question of the age”, said a former Louisiana sugar planter, a question that reveals the profound disagreements and anxieties that affected all sectors of society, as Army officers, Bureau agents, Republican lawmakers, Unionist Conservatives, the Black community and Radical activists all struggled to set the limits, objectives and scope of the Reconstruction process.

Outside of the most conservative Northerners, there was an agreement that the power, land and even citizenship of the Confederate leaders would be permanently taken away. Wade Hampton, the South’s richest man and now a Confederate general, would certainly “not retain his land, even if he retains his head”, announced Owen Lovejoy, a Radical Senator and a close Lincoln ally. But Lincoln and other Moderates hoped for a lenient Reconstruction that included recanting Southerners, and for that reason they were open to the restitution of property and their participation in the political process. Excluding poor White Southerners from confiscation and including them in the process of Reconstruction, they argued, would divide the White South, while an indiscriminate enforcement would create a united bloc of resistance that would “fight the national government until the land was barren of life, and flooded with blood. Would you care to see scenes like those of New York in every Southern city and village?”. Furthermore, limiting confiscation and punishment to the Confederate leadership would still yield great tracks of land, since most large landowners were also enthusiastic secessionists.

The properties of the most prominent Confederates was quickly confiscated, such as Lee's plantation in Arlington, which included a section reserved for Black soldiers

However, on the left the Radical Republicans naturally pushed forward for a more extensive enforcement of the Third Confiscation Act. “Not a single foot of land” had to remain in rebel hands, insisted Stevens. Reconstruction had to “revolutionize Southern institutions, habits, and manners . . . The foundation of their institutions . . . must be broken up and relaid, or all our blood and treasure have been spent in vain.” Stevens’ rhetoric reveals that aside from humanitarian concern for the freedmen, Radicals supported confiscation as a way to complete the destruction of the old Southern order. “The war can be ended only by annihilating that Oligarchy which formed and rules the South and makes the war—by annihilating a state of society”, said the veteran abolitionist Wendell Philipps, who insisted that a Reconstruction without extensive confiscation and disenfranchisement would leave the “large landed proprietors of the South still to domineer over its politics, and makes the negro's freedom a mere sham.”

Confiscation, then, was a necessary part of Reconstruction if slavery and the social system it established were to be truly destroyed. Otherwise, the freedmen would just become landless serfs, still subject to the authority and power of the old planter aristocracy, a situation “more galling than slavery itself” according to George Julian. Within this context, freedom was defined by Radicals in terms similar to those Jefferson had once employed: men free to chart their own destiny thanks to the economic independence land ownership afforded them. In principle, Lincoln and the moderates agreed with Radical philosophies. That’s why they had approved of the Third Confiscation Act after all. But instead of a Revolution, the Moderates envisioned Reconstruction as a practical problem to be solved. The rebel States, Lincoln said, were “out of their proper practical relation with the Union; and the sole object of the government . . . is to again get them into that proper practical relation.” Reconstruction, under this view, was about finding the best way of restoring the Confederacy to that “proper practical relation”.

That’s why Lincoln thought that these debates about the substance of Reconstruction were “pernicious abstractions”, and that to ponder whether “the seceded States, so called, are in the Union or out of it” was “merely a metaphysical question”. Lincoln fully understood that these arguments could result in radically different visions for Reconstruction, but the President felt that he had the duty and power to act to reconstruct the South without needing to wait until Congress settled on a policy. Here, Lincoln’s political objectives converged with his military responsibilities, for he also saw in Reconstruction a chance to weaken and defeat the Confederacy. Thus, while Congress debated, Lincoln exercised his “inherent advantage over Congress in time of war”, by appointing military governors to rule in the areas of Tennessee, Louisiana and Arkansas that came under Union control. These governors would have to grapple not just with guerrilla warfare and discontent populations, but also with the duty of enforcing Congressional directives and Executive proposals. In this regard, one of their greatest challenges was the question of land and labor.

Land and labor, as examined previously, was hotly debated throughout the North, as much in Congress as in newspapers and town halls. But the question was thornier and much more difficult in the South, where Army officers and Bureau agents had to oversee the freedmen’s transition to free labor at the same time as they continued to fight the war. It’s here, too, that the disadvantages of military emancipation became more evident, for the liberation of thousands of slaves created a giant humanitarian crisis even if they constituted a relatively low percentage of the total enslaved population. And finally, it was in their dealings with the freedmen that the military authorities, and through them the entire North, learned of the Black community’s unexpected militancy and own vision for the future. All these factors intersected and shaped the establishment of free labor in the occupied South.

Northern authorities were often surprised by the discovery that Black people had their own agendas and aspirations regarding the post-war world

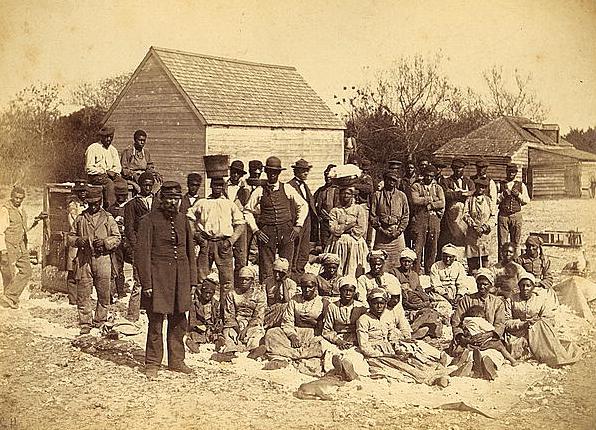

The first “rehearsals for Reconstruction” took place in the South Carolina Sea Islands. The unusual characteristics of slavery in that area, including allowing the enslaved to organize their own labor and even own property, created unique perspectives and aspirations within the 10,000 slaves who had been left when the White population fled after the Union took the islands. They mostly hoped to “chart their own path to free labor”, but with the Yankee soldiers came also “a white host from the North – military officers, Treasury agents, Northern investors and a squad of young teachers and missionaries known as Gideon’s Band.” This last group was the so-called “Gideonites”, young idealists who had already worked assiduously in Maryland. But the Sea Islands offered an even greater opportunity, for there the “political and social foundations will be built anew” while in Maryland their task was limited to “patching the worst parts of the old edifice.”

The “Sea Islands Experiment” became a highly publicized affair, as Northerners, whose knowledge of Black people was often limited to what they had read in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, saw in it a perfect opportunity to see how the enslaved would fare once emancipated. Many, if not most, of the Yankees that flocked to the Sea Islands carried with them paternalistic attitudes and racist assumptions, believing that Black people could only join the free market and become free laborers if guided by benevolent White teachers and advisors. But these beliefs belied genuine concern for the freedmen and a sincere desire to aid them. These commitments were shared by reformers who flocked to the occupied lands in the Mississippi Valley. It was their efforts and activism that secured the creation of the Three Bureaus in middle-1863, and their lobbying also secured the appointment or enhanced the influence of many officers sympathetic to the freedmen, such as Rufus Saxton, E.R.S. Canby, and John Eaton. Their crowning achievement was convincing Lincoln to set aside plots of land, to be given to the Black families of the Sea Islands.

Throughout the liberated Confederate areas, the Freedmen’s Bureau took over the education, health and protection of the freedmen, while the Labor Bureau set conditions for their employment and the Land Bureau worked to confiscate and distribute estates among them. But the abolitionists that dominated local chapters of the Bureaus had to grapple with Army authorities, Northern investors and Treasury agents that weren’t always sympathetic to their goals or to their charges. The problem was increased by the fact that the Bureaus had not been given their own budget, meaning that they needed to use Army personnel. This, naturally, greatly limited their influence wherever the local officers weren’t willing to cooperate. Even within the Bureaus there was the widespread feeling that the freedmen should not be made permanent wards of the State, and that the only way for them to achieve true dignity and freedom was through self-sufficiency, not the aid of the government.

The consequences were that the Union authorities enforced the government’s directives not with the revolutionary vision with which lawmakers had conceived them. In special, military authorities worked under the assumption that some sort of coerced labor would be needed to reactivate the production of cotton and thus the region’s economy. This conviction was reinforced by the pressure of Northern industrialists and investors, who hoped to strike it rich through the cultivation of cotton by free Black labor. These entrepreneurs by and large would agree with Edward S. Philbrick, a member of their ranks who asserted that “the abandonment of slavery did not imply the abandonment of cotton”, but that Black laborers would work more efficiently and profitably now that they were free and could trust in economic rewards and social advancement if they worked hard enough.

As a result, and many months previously to the enactment of the Third Confiscation Act, a system of “compulsory free labor” was developed in the occupied South. The enslaved that came within Union lines would be given three choices: being put to work on abandoned plantations, working for the Army as laborers, or, after the Emancipation Proclamation and especially after Union Mills, joining the Army as soldiers. In all cases, they would sign contracts and receive wages, an acknowledgement of their right to “the fruits of their own labor”, a right Lincoln had once insisted they should always enjoy. The Army would also protect their other rights, offering education to their children, medical care to the infirm or elderly, and forbidding physical punishment. Such a system, those in favor argued, would help manage the humanitarian crisis, reactivate the Southern economy, and allow the freedmen to pay for their own protection and living.

The Port Royal Experiment was the most publicized one, but far from the usual war-time experience of freedmen

This system, “an anomaly born of the exigencies of war, ideology, and politics”, soon proved imperfect, and satisfactory to no one. In the Mississippi Valley, it was found especially unsuitable due to the sheer number of refugees who flocked to the territories controlled by the Union. Directly organizing their labor seemed an impossible task, especially when the Army still had to fight against the rebels and thus could not devote its entire energies to this humanitarian crisis. To solve this problem, in middle-1862 the Army started to lease abandoned plantations to loyal men. As part of the policy of conciliation, loyal Southerners and recanting Confederates were allowed to lease it too after swearing a loyalty oath. Most of the leased plantations, however, ended under the control of Northern leasers, who usually arrived not with idealistic convictions or a genuine sympathy for the freedmen, but a desire to build a fortune in cotton trade.

This “unsavory lot” was motivated by greed and aided by the corruption of army officers and soldiers who also hoped to “pluck the golden goose” of the South. Naturally, the rights of the freedmen were not a priority, especially when they showed their unwillingness to submit to a system that didn’t fully guarantee their rights and didn’t fulfill their aspirations. Most of the freedmen wanted, above everything else, to own and work their own land, free of White coercion and violence. The lease system, with its forced yearly contracts, low wages and “perfect subordination” enforced by the Army, was seen by most as slavery under another name. Constant disputes between employers and employees ensued, as the lessees clamored for more coercive measures, even adopting the planters’ beliefs that physical punishment was the only way to make Black people work. “They work less, have less respect, are less orderly than ever”, they complained.

The lessees also found it difficult to obtain the tools and food they needed and had to face unscrupulous Army officers and the “Army worm”, named like that because, like the Army officers, it always “found ways to appropriate nine tenths of the crop”. But what ultimately doomed the lease system was the collapse of order in the Mississippi Valley, and the resulting increase in violence and chaos. The Union Army, nominally in control, was overwhelmed by the degree of savage violence in a territory as large as France or the Iberian Peninsula. In the areas presumably under Northern control “a system of anarchy reigned” instead, a distraught Confederate admitted. The degree of brutality and destruction increased after the Fall of Vicksburg and Port Hudson, for the weakened Confederate regular forces had to rely in raids, unable to directly face Grant. But maneuvers meant to strain logistics or slow down the enemy had an appalling tendency to degenerate into indiscriminate and disorganized campaigns of looting, arson and murder. Direct casualties, to be sure, remained relatively low, but the continuous chaos impeded commerce, disrupted agriculture and made thousands of fearful citizens flee. The quite brutal policy of forcibly expelling civilians became a tool of the Yankees, who issued decrees that forced non-combattants out, seized their produce and cattle, and confiscated their homes in reprisal for their aid to the guerrillas. "It is harsh and cruel," a soldier admitted, "but whatever we don't take a marauder will".

However, it wasn't only the Federals that engaged in such policies. To prevent Southern resources from falling into the hands of the enemy, rebel armies and guerrillas ordered that all loyal Confederates should leave their homes for the interior, taking everything they could and turning everything they could not over to the Confederacy. But civilians didn't want to give their mules and cattle to the graybacks anymore than they wanted to give them to the bluejackets. Of special contention was the "refugeeing" of the enslaved, an expensive practice that wealthy masters engaged in, forcing their human property deeper into the interior or to far away areas such as Texas. But other masters refused, leaving slaves behind who, they believed, would remain loyal to them. Even in the face of the Union's growing commitment to emancipation, which meant that slaves left behind would just become the enemy's laborers and soldiers, many masters still insisted that the government had no right to move or use their property. When Breckinridge ordered commanders "to remove from any district exposed to . . . or overrun by the enemy the effective male slaves", a Virginia legislator lectured the President, telling him he should "refrain . . . from exercising a power . . . seriously objectionable and prejudicial" to the interests of planters.

The flight of civilians caused thousands of deaths due to exposure, hunger and disease

While people in Richmond debated constitutional niceties, the situation grew desperate in Mississippi and other areas where the Yankees were directly assaulting slavery. When planters and plantation owners refused to move to the interior, the Army and the guerrillas would forcibly expel them, abducting the enslaved to serve as laborers and taking all the foodstuffs and produce for themselves. If they refused, they were simply murdered. Planters who tried to resume their loyalty to the Union and lease land or work with their former slaves found themselves continually threatened by guerrillas that regarded them as traitors and menaced their lives if they refused to move or turn over their property. With civil authority having completely collapsed, guerrilla chieftains and individual commanders became warlords over large swathes of territory, where their men were the real power. Illustrative of this situation was that in a Mississippi county, the selling of a house was completed not by an appearance before a judge or notary, but before the local guerrilla chief, who was given a large amount of cotton and beef in exchange of recognizing the sell and protecting the new owner. The situation made it necessary for thousands to escape, which resulted in the spectacle of once wealthy and proud planters fleeing through swamps with nothing but the clothes on their backs.

Appallingly, the collapse of slavery only inspired further violence on the part of guerrillas, which often decided to just massacre Black laborers who refused to be "refugeed", or attacked those who had already been settled on plantations, murdering the Northern lessee or Southern Tory that was in charge. The Confederates too destroyed boats and impeded river commerce, and routinely razed the land behind Union lines to prevent the enemy from using it. The result was that lessees lived in constant fear of having their laborers murdered, the land they leased destroyed, and their own lives ended. In response, Grant ordered a series of anti-guerrilla sweeps, declaring that all rebels found under arms should be immediately executed. Union guerrillas, not to be outdone by their rebel counterparts, took to enforcing these terrible decrees, plundering farms and plantations, and coldly butchering those who didn't flee or refused to take the loyalty oath. These bloody actions were taken without the direct orders of the Yankee commanders, but often with their tacit approval.

But these actions could not stop the constant depredations of Confederate soldiers and guerrillas. The Army, unable to patrol the enormous territory under its control, was helpless to aid lessees when Confederate marauders attacked. Through 1863, over thirty lessees were murdered along with thousands of freedmen, in many scenes of gory massacre. One lessee, for example, found the heads of his two sons on his doorstep, a note telling him to leave. He preferred to kill himself. Recanting Confederates fared even worse, for they were considered traitors to their section and thus held in greater contempt. “We live in terror and dismay, sir. Daily deadly threats come in against my husband’s life since he turned Union”, a woman desperately wrote to her local commander, begging for some protection. “We know these men don’t hesitate to murder women and children in the most horrendous ways. Please sir, we need soldiers to protect us loyal people.”

Such a violent situation caused the lessee system to crumble during 1863. Submerged in constant disputes and constant threats, most lessees found it impossible to turn a profit despite the sky-high price of cotton. The increase of guerrilla activity and the worsening of the humanitarian crisis after the fall of Vicksburg created an even more desperate situation. Disillusioned, most returned North by late 1863. This allowed for an alternate system, one that encouraged Black independence and land ownership, to take hold. The “home farm” system was first instituted by General John Eaton in the Mississippi Valley in early 1863. Instead of leasing the land to Northern factors or loyal planters, the abandoned, and later confiscated, plantations would be turned over to the freemen, who were free to work them as they saw fit. The Army would ensure their safety and bring them food and tools, in exchange for the cotton they grew. The need to balance the Army’s needs with the freedmen’s aspirations meant that most of the home farms created were relatively small. Nonetheless, and especially after the Third Confiscation Act, thousands of freedmen were settled in thousands of acres of confiscated land, forty acres being given to each family alongside a title to the land under the terms of the law.

In practice, the home farm project proved far more successful than leasing. The slaves that had flooded the Union strongholds were quickly resettled in confiscated plantations, while those who had been abandoned and welcomed the Yankees would often be given command over their former owner's plantations on the spot. Many a fleeing master discovered then that their expectations of loyalty had been sorely mistaken. The young Katherine Stone was "hurt and perplexed" when she learned that her family's butler, instead of defending their plantation, had invited the Yankees in and become the leader of the home farm they established. It was this show of loyalty to the National cause rather than the rebel authorities that inspired Grant and other Union commanders to arm Black refugees, often giving them whatever surplus arms were available and formally organizing them as USCT regiments only later. Consequently, wherever the Union Army marched, they liberated and armed the enslaved, a fulfillment of "the worst nightmares of the planter class".

The Negro Paradise of Davis Bend

Thus, the liberation of the enslaved, their arming and organization, and the redistribution of land in their favor became the most effective and accepted way to deal with the crisis. To make it easier for the Army, the freedmen were usually given collective control over large plantations, with the promise that it would be divided into family plots at the end of the war. USCT regiments formed out of the home farm’s men would be organized and posted to protect the residents, creating a more constant and motivated force that would free White soldiers to remain with the main army commands. These “independent Negro cultivators” managed to raise more cotton and protect themselves more effectively from Confederates than the “sharp sighted speculators” had done. One particular story of success is that of Davis Bend, the plantation Confederate Secretary of War Jefferson Davis had owned with his brother Joseph. Ordered by Grant to create a “Negro paradise” there, Eaton settled several Black families, which went on to raise 2,000 bales of cotton and create their own government complete with judges and sheriffs.

From its inception, the home farm system earned bitter criticism, especially from White Southerners who believed that such a system would only encourage “laziness and vagrancy” among freedmen. “Only the whip and the hard hand of the overseer”, could revive agriculture, they asserted, and pointed to the fact that many freedmen preferred to cultivate food for their families or focus on their children’s education rather than devoting all their energies to cotton cultivation as under slavery. As Black activists said in outrage, these criticisms were invalid and hypocritical, for whenever White men worked only for their own subsistence they were lauded as Jeffersonian heroes and self-reliant farmers, while Black laborers were criticized as “lazy, indolent and improvident for the future” for wanting to concentrate on their own living instead of working for the benefit and under the control of Whites. Especially contentious was the refusal of many freedmen to cultivate cotton, “the slave crop” that they identified with slavery and submission to White authority but one that Yankees usually saw as the only way to run the home farms efficiently and profitably.

The success of the home farm system became more apparent in the later half of 1863, after the vigorous enforcement of the Third Confiscation Act and the weakening of the Confederates thanks to Grant’s victory at Liberty allowed for millions of acres of land to come under Union control. Union Mills also changed Yankee aptitudes towards Black Union soldiers, and whereas their recruitment was once seen as an invitation to butchery and servile insurrection, now hundreds more regiments were being mustered into service to defend the home farms. These regiments, which wounded Southern pride so deeply, proved adept when it came to countering rebel guerrillas. After the war, many leaders of the Black community and Reconstruction came from the home farm regiments, whose military service and experience fighting the Confederates resulted in a firm commitment to defend the new order and demand and protect their rights. As soon as the war ended, and with many Yankees regiment returning home, these regiments of radicalized Black soldiers would be the ones left behind to patrol the occupied South and enforce Reconstruction.

The arrival of the new Bureau authorities also resulted in great changes, as Bureau agents settled freedmen on confiscated plantations, protected them from abuse and violence, and regulated the labor of those who still worked for wages. The labor system under the Bureaus, a Northern lessee complained, was “framed in the exclusive interest of the negro and in the non-recognition of the moral sense and patriotism of the white man.” But the Bureaus also worked to take care of poor White refugees, and thousands of White yeomen also were settled in confiscated plantations. The weak Unionist sentiment in many parts of the South ensued that these “Union colonies” would also be defended by USCT regiments, and many Bureau schools and hospitals were racially integrated. Though this naturally contributed to racial tensions, the experience of war and emancipation also caused many Southerners to leave behind their prejudices, and by 1864 a Northern radical touring the South could be astonished by the fact that in cities like Jackson, Nashville and Vicksburg “Negroes and Whites work together, go to school together, and even take part in local governments together. Who could have predicted this wondrous transformation of public feeling?”

Despite the fact that many Union authorities remained opposed to the idea of Black land-ownership, one calling it “a wild scheme, that out-radicals all the radicalism I ever heard of”, by the middle of 1864 the home farm system had taken over and Bureau agents continued to enforce the Confiscation Act

en large to obtain more land for more home farms. The failure of the lease system, constant Confederate violence and the failures and tribulations of Reconstruction seemed to convince most Yankees, including Lincoln, that this was the way forward. As the

New York Times noted, deeply rooted “theories and prejudices” were being discarded, and ideas that had seemed impossible just a year ago, such as Black landownership and Black suffrage, were now taking hold among Northern Republicans. Consequently, when the Congress passed George Julian’s Southern Homestead bill, which gave Black soldiers 10 acres of land for their service and declared that confiscated land would be taken “in perpetuity”, Lincoln signed it, commenting the success of land redistribution “in the work of the colored people’s moral and physical elevation” and how experiments in Black land ownership were leading to “an earlier and happier consummation than the most sanguine friends of the freedmen could reasonably expect.”

The Home Farm system proved succesful for the management of Black labor and the humanitarian crisis

In early 1864, a white resident of Chattanooga noted that, even with the war still raging on, life was “so different from what it used to be”. Indeed, revolutionary changes had come to the occupied South. With Bureau schools and hospitals dotting the land, and some 200,000 Black people settled in some 5 million acres of land, this new South looked nothing like the old one. But as it often happens, the Revolution kept inexorably moving forward, and while these astounding changes would have received “unqualified applause” from Northern Republicans just a year ago, now they didn’t seem enough. The issues shifted and with “emancipation now an article of party faith”, most Republicans now were debating the post-war status of Black people. For the Radicals, the Revolution would not be complete until “blacks had been guaranteed education, access to land, and, most importantly, the ballot”. The struggle to define the post-war order continued, and was intensified, instead of settled, by Lincoln’s Declaration of Amnesty and Reconstruction, delivered as part of his annual message to Congress in December, 1863.

The message was borne out of the war experiences of 1863, the failure of the lease system and the first successes of land redistribution, and the thriving debate over the meaning of freedom and citizenship that raged in the North towards the end of the year. It was the first time a coherent program for Reconstruction had been articulated by the Union’s leaders. “Under the sharp discipline of civil war the nation is beginning a new life”, Lincoln declared, remarking that the liberation of thousands of slaves and the process of Reconstruction would lead to “changes as profound as those of the first revolution”. The President also paid homage to the “heroism and patriotism” of the more than 200,000 Black Union soldiers, “whose commitment to the cause of freedom is as noble and enduring as that of the best white men in our service”. Finally, Lincoln presented his proclamation, with which he hoped to start a process of Reconstruction that would see “the home of freedom disenthralled, regenerated, enlarged, and perpetuated.”

In the proclamation, Lincoln declared that rebels that desired “to resume their allegiance to the United States and to reinaugurate loyal State governments” would receive a full pardon and amnesty, after swearing an oath of allegiance to the United States and all of its laws and proclamations. This blanket offer was not extended to anybody who had held civil office, state or Federal, under “the so-called Confederate states”; served in its armed forces with the equivalent rank of colonel or superior; or had held civil or military office, state or Federal, under the United States but had then joined the rebellion. People who had engaged in “abominable crimes against the laws of war and nations” would also be exempted, Lincoln warning that they would be tried under the laws passed by Congress. Those who had had their properties confiscated would enjoy its full restitution, except for slaves, if they resumed their loyalty before July 4th, 1865. Should any of those who applied for a pardon engage in future disloyal activities against the US in “a cruel and an astounding breach of faith”, they would be liable for confiscation, even of properties already returned, and also for treason trials.

The Proclamation continued, stating that loyal citizens and those who had taken the oath and resumed their loyalty could organize loyal State governments that would be recognized by his administration as the legitimate government of the state if they constituted 25% of the citizens that had voted in the last presidential election. To begin this process, the loyal citizens would have to elect a constitutional convention, that would then draft a new state constitution which had to prohibit slavery. Any provision in regard to the freedmen that “shall recognize and declare their permanent freedom, provide for their education, and which may yet be consistent, as a temporary arrangement, with their present condition as a laboring, landless, and homeless class” would be welcomed by the President, but not required. As for qualifications, only those who could take the “ironclad oath”, meaning that they had never aided the Confederacy willingly in any way, could be elected to a seat in these Constitutional Conventions.

The Heroism of the Black Soldiers of the Union Army helped to transform the nation

The most revolutionary parts of the Proclamation came at the end. Lincoln declared that the lands confiscated from those exempted from pardons would never be restored; likewise, land confiscated from anybody who had not resumed their loyalty before July 4th 1865 would be permanently forfeited. Land on which the freedmen had been settled was theirs, “in perpetuity”, and the new state governments had to grant them a secure title. Finally, suffrage was extended to Black men “on the basis of military service and intelligence”, allowing them to take part in the Reconstruction process. Black voters would count to reach the required 25% of the pre-war voter total, opening the possibility of a Reconstruction dominated by Black voters in states where African Americans constituted a large minority or even a majority of the population. This was nothing less than a Revolution in earnest.

Lincoln’s measures, as usual, combined sincere beliefs with practicality. Lincoln had already privately told a New York Republican that he favored suffrage for Blacks the previous summer after Union Mills, but had said nothing publicly. This was due to the unpopularity of Black suffrage among Northerners. But just like how emancipation had come to be accepted, it seemed now that giving the ballot to at least some African Americans was being accepted by more and more Yankees. “I find that almost all who are willing to have colored men fight are willing to have them vote”, wrote Secretary Chase for instance. The overwhelming Republican triumph in the fall elections and the achievements of the Maryland Constitutional Convention certainly helped, for they made Lincoln feel secure in his political position and brought the issue of Black suffrage to the center of the political debate. It’s certainly not a coincidence that Lincoln first timidly raised the issue publicly after those events, and although the passing mention of “the recognition of the colored people’s civil and political rights” evoked predictable outrage, Lincoln dismissed it freely as “the opinions of a few Copperheads”. One month later, and he included Black suffrage as part of Reconstruction.

But underneath this Radical front, Lincoln’s Reconstruction plan also included some measures that disquieted Radicals. Though the exclusions of many Confederate leaders were welcome, Lincoln’s measures left the great majority of White Southerners, including low level government officials and private planters that had supported secession but hadn’t joined the Confederate government, free to take part in the Reconstruction process. Lincoln claimed that all loyal men agreed that it was necessary to keep “the rebellious populations from overwhelming and outvoting the loyal minority”, but most Radicals believed that without universal suffrage that would inevitably happen, since the qualified suffrage of Lincoln’s formula would only allow a tiny percentage of the South’s Black people to vote. The plan, moreover, did not force the Southern governments to include any disposition pertaining to Black people’s education or other political and civil rights such as jury service, and there were real fears that confiscation and other measures needed to continue the Revolution would be stopped if Federal oversight was quickly ended.

Indeed, a hasty end to Federal intervention was the greater Radical worry, for most had become convinced that a lengthy period of Federal rule, during which the South could be socially and politically reconstructed, was needed before the states were reintegrated into the Union. Lincoln’s plan promised a quick restoration of governments that would necessarily include former Confederates whose Unionism was suspect. These “inverted pyramids”, as the New York

World called them because “only a few thousand voters would control the destiny of entire states”, could certainly not function as the basis for stable governments or for the more far-reaching changes Radicals advocated for. Furthermore, while Lincoln sincerely believed in Black suffrage as the right thing to do, savvy Radicals were quick to recognize that for the President it was mostly another “carrot and stick”, because it would push planters and other Confederates to quickly pledge loyalty to the Union and take command of the Reconstruction process lest Black people do it first. For that reason, Lincoln would allow the new governments ample capacity to regulate the transition to free labor and the new state institutions, which smacked of betrayal to Radicals committed to deep and revolutionary changes in Southern life.

The Second American Revolution had already begun. The questions related to its extent and objectives

The “Quarter Plan” as it became known, was not a policy set in stone from which Lincoln was never willing to deviate. The President never thought of it as final policy for Reconstruction, but, similarly to Emancipation, he believed in the Plan as a military measure that would create “a rallying point– a plan of action”, causing snowballing defections from the Confederacy and achieving a faster end to the war. The Quarter Plan, Lincoln said, “is the best the Executive can present, with his present impressions”, but “it must not be understood that no other possible mode would be acceptable”. It didn’t lay a comprehensible blueprint for the South’s future once the war was over, but it wasn’t meant to. Nonetheless, the implementation of the plan in the Deep South quickly revealed its revolutionary implications, allowing for new groups of power to emerge, and creating serious differences among Northern lawmakers. Nowhere was this more evident than in Louisiana, whose experience of Reconstruction would profoundly affect and even shape the President’s and the Congress’ intentions and perceptions regarding the future, and result in a struggle between them as they both tried to take charge.