Quote ?Radar has been around since 1908 ITTL

Only after his death it was found out how for years Hermann von Helmholtz had used magnetic oscillations to reheat his meals when working late in the laboratory.

Last edited:

Quote ?Radar has been around since 1908 ITTL

That would be in character.Quote ?

Only after his death it was found out how for years Hermann von Helmholtz had used magnetic oscillations to reheat his meals when working late in the laboratory.

It just occurs to me that military oversight over the national motor pool will obviously mean an early introduction of roadworthiness inspections (if only to ensure the owners don't modify them beyond usefulness). This is likely to be the job of the army. It will make German streets much safer early on, but since this does not affect the kind of upmarket cars that don't get the tax breaks and subsidies associated with entry into the mobilisation roster, it will probably create an interesting privilege. If you have the money to buy a 'taxed' car (import or domestic nonstandard), you are also exempt from inspections and can modify it as you wish. We will probably see heavily individualised cars rolling around German streets to advertise their owners' affluence, and 'rich person driving unsafe car' will be a continued source of irritation in the Social Democratic press coverage of traffic accidents.German cars are not bad, they just aren't designed with an affluent global export market in mind. It's a question of culture, and German management, engineering and labour can just as easily give you VW as it can Mercedes Benz. Here, the German car industry became unified not by consumer demand (as happened to the US industry in its consolidation phase), but by military demand. Its champions were created because the army wanted a motorisation programme it could not afford. The structure they came up with created incentives to car ownership as long as the vehicles met certain specifications. These were in force, in some fashion, until the 1970s. It gives you a design culture that is slow to change and focused on ruggedness, reliability, and ease of repair.

This is the root of it: https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...ntinuation-thread.448981/page-8#post-17741339

there are some German companies making high-end cars, but they are not very widespread outside the country. The symbols of 'the good life' are associated with Paris and London ITTL. Wealthy people want the trappings of civilised affluence, not something they mentally associate with spartan simplicity and Central European farm life. So perversely, you can get a very good German luxury car for less than you would pay for a Rolls Royce or a Chrysler, but even though it marches the performance, it will not give you the same cachet.

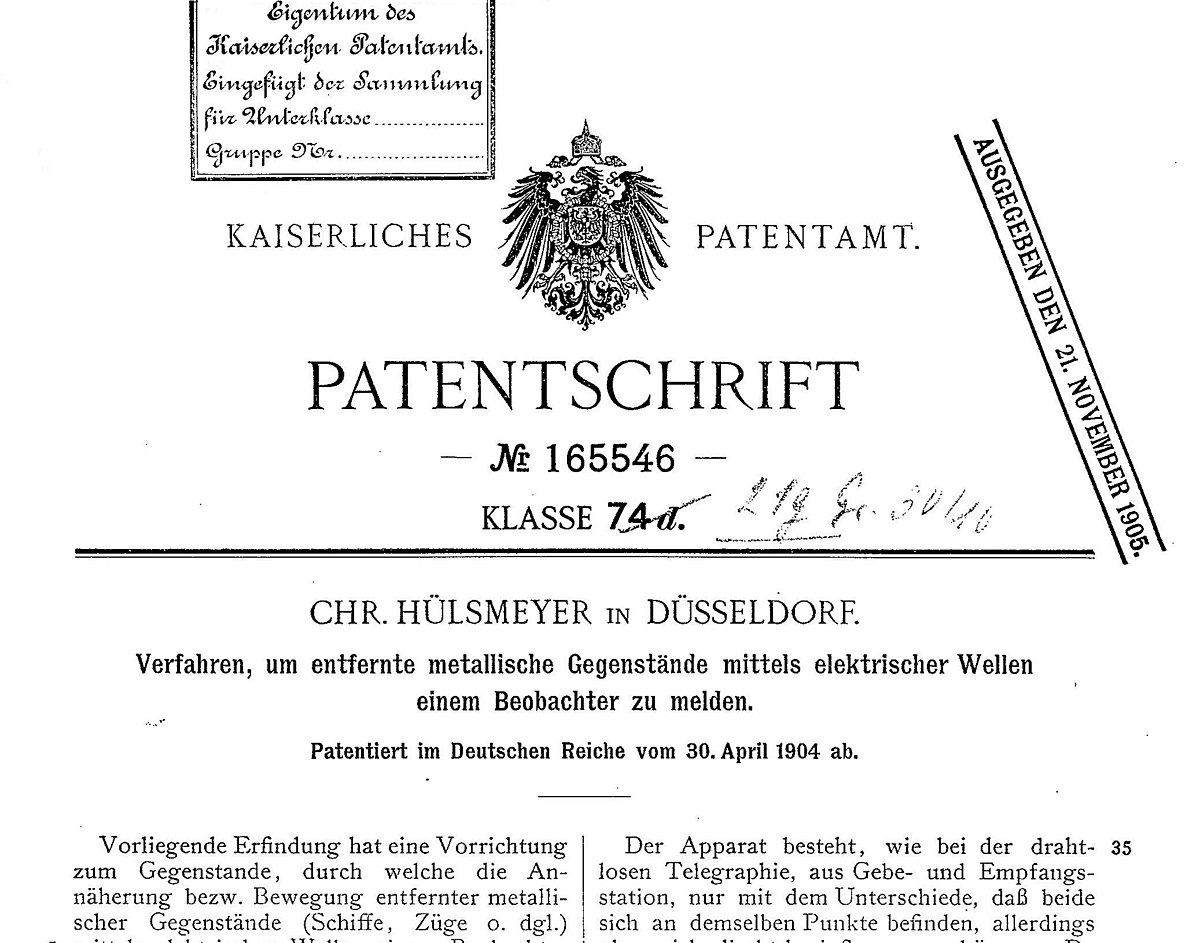

Thanks.This is the guy: Christian Hülsmeyer.

Der 7. Sinn, Achtung Panzer, 1986The army. It will make German streets much safer.

East Prussia is doing okay, for a rural backwater with more history than future. the imperial government put serious money into repairting the war damage, and a lot of it went to the noble families who own so much of the province. As a result it is a bit of a Junker's Disneyland, a place where a lifestyle that is dying elsewhere goes on parade. It's very much Old Prussia, zackzack, lots of officers come from there or wish they did. And obviously they do have weird accents, but nowhere near as weird as the Bavarians or Saxons.How is east prussia doing, and Holstein and sch something? Do east prussian still have weird accents?

What is the proper dialect of germany, whats their Parisians french?

Certainly extremely contentious. There are Austrians, and not a few, who deliberately imitate Prussian speech patterns. Others deliberately eschew them. The court is very puntilious about 'heuer' and 'Jänner'.And presumably Austria is another story entirely. Even IOTL Germans have to take mandatory language classes if they want a permanent job in Austrian televison. Having any program presented in too 'German' German is seen as unacceptable.

German cars are not bad, they just aren't designed with an affluent global export market in mind. It's a question of culture, and German management, engineering and labour can just as easily give you VW as it can Mercedes Benz. Here, the German car industry became unified not by consumer demand (as happened to the US industry in its consolidation phase), but by military demand. Its champions were created because the army wanted a motorisation programme it could not afford. The structure they came up with created incentives to car ownership as long as the vehicles met certain specifications. These were in force, in some fashion, until the 1970s. It gives you a design culture that is slow to change and focused on ruggedness, reliability, and ease of repair.

This is the root of it: https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...ntinuation-thread.448981/page-8#post-17741339

there are some German companies making high-end cars, but they are not very widespread outside the country. The symbols of 'the good life' are associated with Paris and London ITTL. Wealthy people want the trappings of civilised affluence, not something they mentally associate with spartan simplicity and Central European farm life. So perversely, you can get a very good German luxury car for less than you would pay for a Rolls Royce or a Chrysler, but even though it marches the performance, it will not give you the same cachet.

Not far, unless you toned it down to a charming reminder of local identity. Then it could support a political career in the Zentrumspartei, I guess. Not the DKP - soooo unmilitary.So, where would my Grandmothers' Wallhausen Platt (Rheinland-Pfalz) take me in this world?

I think the idea can come from the USA. The market is big enough to support high-end brands, and US companies understand marketing very well. Mass production niche is taken, but selling a much nicer, distinctive vehiocle at a higher, but still manageable price is a vacuum that will be filled. Ford can't do it - who wants a Ford?I think it's more likely that we don't see the development of high end car brands[1]. Instead we simply see most major car brand having some high end models. I don't think we should underestimate how much of the German dominance of high end brand is because of cross-brand synergy between the different brand and from a general reputation of German enginering. The problem outside Japan I can't really see another country develop the same reputation: Sweden have some of the reputation, but they also have a reputation for a obsession of function over form.

[1]Luxury brand will still exist

I think the idea can come from the USA. The market is big enough to support high-end brands, and US companies understand marketing very well. Mass production niche is taken, but selling a much nicer, distinctive vehiocle at a higher, but still manageable price is a vacuum that will be filled. Ford can't do it - who wants a Ford?

I agree, that kind of identification of a nation with upmarket cars is not going to happen. International success is going to be brand-based. Not 'French' but Citroen, not 'American' but Chrysler and Cadillac. Similar to what Ferrari has - nobody is going to call a Ferrari an "Italian car". But in this TL, people will "know" that Germany doesn't really make that kind of car.But some of the point is that if you’re not German, and you hear the word “German Car” you see a high end car on your inner eye. It’s harder to make that connections if the country in question is also producing cars seen as shoddy. It’s why the German cross brand synergy have only improved as VW moved away from cheap cars, Opel have become seen as “German” and Trabant have disappeared“. American car did have something of a high end reputation after the war in OTL, but in the end without cross brand synergy this didn’t last.

Darn!Not far, unless you toned it down to a charming reminder of local identity. Then it could support a political career in the Zentrumspartei, I guess. Not the DKP - soooo unmilitary.

National Brandenburg Central, Der Weg nach Walhalla episode 4: "Nullpunkt", earlier that evening, 9 July 1965 [post canon]The German car industry became unified not by consumer demand (as happened to the US industry in its consolidation phase), but by military demand.