Chapter 21

Supremacy

“By their subjugation, he remains the glorious victor and is raised by his renowned triumph to the shining stars of the heavens. Rightly he has frightened some enemies, the breakers of oaths and treaties, into keeping with the holy union by meeting out on them harsh punishments.”

- Matthias Gabler, 1523[1]

“Dabo tibi regem in furore meo”

I will give you a king in my rage

- Giles of Rome, Hosea 13:11

As Spring gave way to an early Summer, Christian II led his triumphant army North along the Oxen Road

[2], arriving at the vibrant market town of Viborg in early June 1523. As the king’s outriders reached the city, they found that whole new neighbourhoods of canvas and velvet tents had sprung up outside the city gates: Representatives from the isles, the Sound Provinces and Eastern Jutland all having converged on the city to attend the first

Estates General[3] in a generation.

The former capital of the Lords Declarent had been conquered by Clement Andersen’s peasant and burgher army shortly before the royal invasion of the duchies. The town which Poul Helgesen had once described as a place where “...

evil had grown to such a degree that this city [...]

became the most nefarious den of all kinds of ungodliness and profanation.”

[4] was therefore still under martial law by the time of the king’s arrival.

When the lords of Jutland raised the banner of rebellion, it was not for nothing that Viborg had been their staging point. The city’s ancient pedigree as the site of the regional assembly (and traditional place of royal acclamation) had granted Frederick I much needed legitimacy when he received the rebel crown from the Jutlandic council.

Just like his pretender uncle, Christian II knew full well the symbolic value of the city. It is well documented that the royal government deliberately chose the nesting ground for the rebellion as a way to signal the totality of the crown’s victory: The cathedral square where the king’s laws had been burned to signal the rising would now be re-appropriated to stage the final stroke against the conservative opposition.

It has often been noted that the timing of the convention could not have been better for the king’s programme as out of all the estates of quality, only the crown had emerged strengthened from the carnage of the Ducal Feud. The high nobility, temporal as well as ecclesiastical, had, conversely, been decimated by the civil war. The most prominent estate, the Lords Spiritual, had been almost halved numerically through the flight of Jørgen Friis, Iver Munk and Niels Stygge Rosenkrantz. Furthermore, the remaining prelates were either long-time Oldenburg loyalists (like chancellor Ove Bille) or low-born acolytes (such as archbishop Christiern Pedersen) who had been directly appointed by Christian II. Compared to the coronation negotiations of 1513 where Birger Gunnersen had presented an insurmountable challenge to the king’s agenda, the ecclesiastical estate of 1523 appeared to be more of a rubber stamp for the crown than an independent institution.

Things were not much better within the ranks of the temporal nobility. The very raison d’etre of the “armoured estate” was to defend the realm; the knighthood quite simply derived its status and privileges from such military service. Indeed, the lower gentry had stressed this point during the accession negotiations in 1513 by noting that: “...

Denmark is a free and elective realm and whatever attack or feud that should be wrought on Denmark’s realm, we are the ones who are to repel it.”

[5]

The fact that several members of the nobility had actively instigated such a feud naturally put a huge dent in the aristocracy’s credibility. Furthermore, the war had created deep cleavages within the military caste. The hitherto unseen bloodletting and battlefield executions had fatally weakened the cohesion of the Lords Temporal. Besides, many of those ancient families, who in times past would have been instrumental in checking the power of the crown, were now firmly in the king’s pocket. The Gøye, Bille and Gyldenstjerne clans had become Christian II’s willing enforcers whilst, conversely, the surviving members of the rebel families of Krabbe and Rosenkrantz were left at the king’s mercurial mercy. Others, such as Henrik Krummedige, who might otherwise have favoured the cause of councilarism, were off fighting the rebels in Västergötland.

To cope with the Frederickian crisis, the king had raised members of the lower gentry - Søren Norby being the most prominent - to serve him both in government and in the field. As bad as that might have been in the eyes of the high nobility, the fact that commoners, those born unfree

[6], had become part and parcel to the crown’s affairs was positively mortifying. Hans Mikkelsen, Clement Andersen and Tile Giseler had all proven indispensable in managing and directing the royal cause during the feud. The demands of the war effort had caused the loyalist gentry to tolerate their presence, but to their great horror, Christian II had not thrown his burgher aides aside the moment his enemies had been subdued.

Quite the contrary, the Estates General would prove just how much stock the king had come to place in his common advisors and captains.

The Knight Saint George.

Mural painting in the parish church of Aale, Skanderborg fief, by an unknown artist ca. 1500-1525. Saint George was a popular saint in late medieval Scandinavia, being, for example, especially favoured by Christian II’s Lord Admiral Søren Norby. In this mural painting from Eastern Jutland, the saint is depicted as a fully armed and armoured member of the noble estate. Military service was the rite de passage which legitimised the privileges of Denmark’s aristocracy. Perhaps, the mural was commissioned by a member of the local gentry as a way to impress the martial dominance of the nobility on the local peasants in the turbulent times of the 1520s.

Financially speaking, the realm was on the verge of bankruptcy. A decade’s worth of intermittent warfare in Sweden had been followed by only the shortest respite before the Ducal Feud put new strains on the royal exchequer. Loans from the merchant classes in the Sound Provinces and the assistance of Christian’s North German allies had kept the realm from imploding fiscally, but it was widely accepted that sweeping reforms were needed.

Following the same procedure as at the Odense Diet, the king pronounced the fiefs and debts of the rebels to be forfeit. Instead the West Jutland fiefs were reclaimed by the crown’s privy purse. In turn they were to be enfeoffed as account fiefs to loyalist nobles. Likewise, those noblemen who had not done their utmost to defend the rights of the king were expected to willingly renounce any claims which they might have held against Christian II.

The return of a large amount of pledge and service fiefs to royal control, however, did not solve the urgent need for ready coin. Although Lübeck was on the defensive, hemmed in by advancing Mecklenburgian troops and a strangling naval blockade, the city had not yet been brought to heel. The potential need for a fresh offensive could not be discounted and the Västgöta lords were still causing trouble for Henrik Krummedige’s viceregal government in Stockholm.

The imposition of extraordinary taxes was a dangerous move in early modern Europe, but none of the estates saw any other way out of the economic predicament. However, the remnants of the council-constitutionalist wing within the council of the realm immediately refused to participate in the “national levy” - referring to their rights of tax exemption, as stipulated in the king’s accession charter. Instead, the councilors proposed a new extraordinary tax solely for the peasants and burghers, which they, in a bizarre miscalculation, termed the ‘Royal Tax’

[7].

It has often been noted in the litterature that the high nobility’s position during the Viborg Diet seemed to be completely out of touch with the apparent political realities of the day. When Jens Andersen Beldenak delivered the proposal, Clement Andersen immediately asked why the commoners should pay for the destruction caused by the feud, when the war had been won “...

not because of, but in the face of the gentry’s arms.”

[8] Andersen’s claim might have been hyperbolic, but the notion that the burghers and peasants, who had been amongst the crown’s most ardent defenders, should bear the sole burden of taxation was absolutely unthinkable.

Matters were only exasperated when, on the third day of the diet, the king began to appoint new castellans at the vacant fiefs in Jutland. Christian II’s desire to see Clement Andersen invested with the rich and powerful fief of Aalborghus caused a storm of protests amongst the moderate and conservative nobles of Northern Jutland. Andersen was an unfree commoner, and although he had proven a diligent servant in the field, the notion of a simple burgher lording over them made the traditionalist Jutlandic gentry shake with indignation. Fuming with rage, the king supposedly slammed his fist on the council table and furiously declared that if “...

my most beloved council of gentlemen had obstructed me so in the recent feud and war as they have done in the matter of peace, then surely I should not be sitting here, but the crown of Denmark’s realm instead be worn by knaves and rogues.” Thanks to the intervention of Mogens Gøye, tempers were cooled and negotiations postponed to the following day.

When the estates met on the 23rd of June, preparations were well under way for the celebration of the Nativity of Saint John, the saint after whom the king’s father had been named. The noble opposition now proposed a compromise, where Clement Andersen would be ennobled on account of his military service. Thereby, he would fulfill the accession charter’s stipulations as to who could be appointed fief-holder. It was an extraordinary concession, as the ennoblement of a commoner was an extremely rare phenomenon, but the king drily replied that if he were to do so, then a great many men would have to be raised to the aristocracy as well. This, however, the council-constitutionalists were not prepared to accept. Pressing his advantage, Christian II now openly brought the matter before the entirety of the Estates General. The mood of the delegates had been soured by the intransigence of the high nobility and a great many now spoke in favour of the king’s prerogative to appoint fief-holders without the consent of the council of the realm. Confirmed in his majority, Christian II simply ignored the objections raised by the opposition and enfeoffed Clement Andersen and other supporters on the authority granted by “...

the consent of the estates in Viborg assembled.”

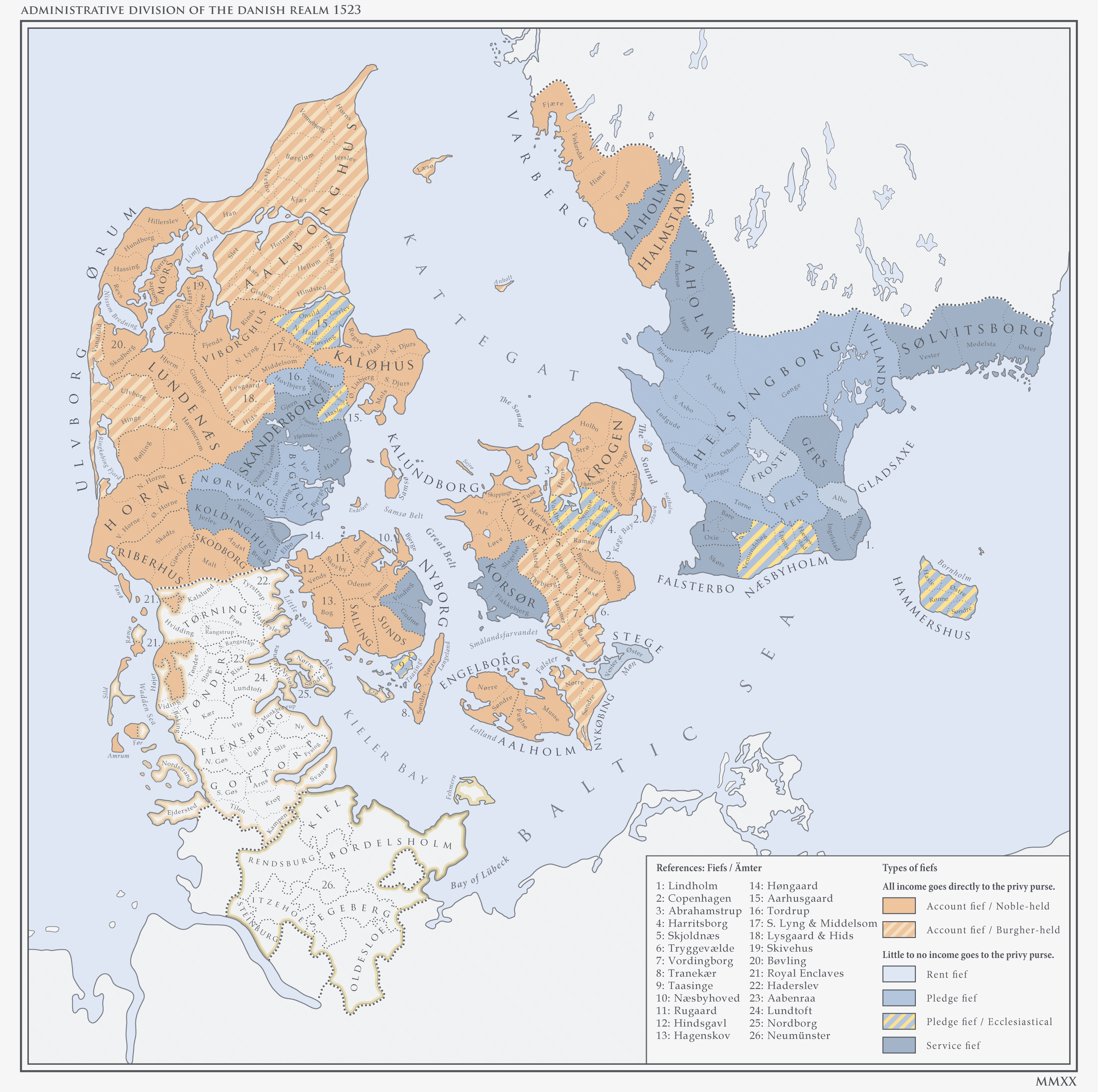

Map of the Danish realm, 1523.

The de-facto acceptance of burgher fief-holders proved to be a great blow to the power of the Danish aristocracy. For an explanation of the various forms of enfeoffment in late-medieval/early modern Denmark, please refer to Chapter 1.

The king’s high-handed disregard of the conservative opposition hardened the attitudes of the high nobility considerably. Eiler Bryske, for example, now switched sides and openly lamented the king’s programme of reclamation. Bryske had been driven from his own fief of Lundenæs by Tyge Krabbe and ever since pursued an aggressive policy towards the rebels

[9]. However, he also remained a committed champion of the privileges of his estate and one might well speculate whether the June negotiations had not made the 40-something years old knight regret his previous loyalty to the king. Joining Bryske was also Jens Andersen Beldenak, the low-born bishop of Odense. Beldenak’s father had been a cobbler from Northern Jutland and his sudden alliance with the councilar aristocracy bore an uncanny resemblance to that of Birger Gunnersen a decade earlier. However, unlike the late archbishop, Beldenak lacked the gravitas, diplomatic skill and high-office to successfully weld the fragmented opposition groups into a coherent front. Besides, his own desire to safeguard the traditional independence of the church was deeply resented by both a society wholeheartedly set on reform and an archbishop beholden to the crown.

When the matter of the Royal Tax was brought up again in private negotiations between the king and the council at the Viborg episcopal palace, Eiler Bryske and the bishop of Odense consequently joined other disgruntled traditionalists in a forceful declaration that the restored peace and tranquillity of the realm entirely depended on the king’s respect of his accession charter. If he did not, they would neither accept the proposed plan for financial reconstruction nor contribute to the measure of extraordinary taxation. The opposition knew full well that they would have to make certain concessions, but they were not prepared to let the king ride complete roughshod over their ancient privileges. Gravely, Beldenak reminded the king

[10] that his power was temporal - in the inherent meaning of the word. He would, in due course, pass from the world, and his authority return to its source - the council of the realm, the eternal representatives of the Danish realm’s sovereignty. If he would not heed their advice, the bishop continued, then his councillors would have to act in the best interest of the “...

free and elective realm of Denmark.”

It was a threat as markedly dramatic and pompous as it was hollow. The Ducal Feud had exposed the flaws of the

monarchia mixta by proving that any constitutional disagreement could only be settled through violence. Seen in this perspective, the Gottorpian crisis had been little more than a legal debate, albeit one causing a fair bit more bloodshed than a contemporary courtroom scuffle. As such, the moment Christian II sentenced Predbjørn Podebusk to death on the field of Hillerslev, the executioner’s sword had not only smitten off the head of the preeminent Lord Declarent, but also that of the entire constitutional system.

The foolhardy stubbornness of the council-constitutionalists finally convinced the king to break the stalemate by force. As the two sides withdrew for the evening, Christian II confided in Søren Norby that he was determined to “...

take hold of the obstinate lords by the scruff of their necks.”

[11] We know now that the broad outlines of the royal programme for the Viborg Diet had been planned months in advance by the king and his supporters, but it is indisputable that the most radical points were only finalised the night before the fateful Tuesday meeting of the 26th of June.

When the two sides reconvened in the morning, Bryske, Beldenak and the other members of the opposition must have noted upon arrival, that the gateway to the bishop’s palace was guarded by a substantial amount of liveried men-at-arms. Paying it little mind, they entered the council hall where they found the room cleared, with the king seated on a dias, attended to by his chief generals Anders Bille, Henrik Gøye, Søren Norby and Otte Krumpen. Just below the king, Hans Mikkelsen, Christiern Pedersen and Mogens Gøye sat at attention behind a long wooden table. Along the galleries, other representatives of the Estates stood waiting whilst the walls were lined with royal halberdiers dressed in “...

bright breastplates and plumes of scarlet and gold.”

Saint Helena Before the Pope by Bernard van Orley,

ca. 1525. In what many art historians have described as van Orley’s pièce de résistance,

Queen Elisabeth is depicted as the beatified mother of Constantine the Great, while her husband, Christian II, takes on the role of the supreme emperor. The Danish flag is featured prominently, being held aloft by a young squire immediately behind the king, whilst, in the background the Dannebrog

is also flown by a large host of soldiers.

As the traditionalists filed in, Hans Mikkelsen rose to greet them and declared that the king had charged him, in his capacity as Master Secretary, with reading the crown’s final reply to their demands.

Essentially, Mikkelsen summarised, the main issue dividing the two parties was the question of rights and restrictions as stipulated in the accession charter. All other disputes stemmed from this great matter. The opposition simply refused to accept the king’s position, because they based their argument on the legal stipulations of the charter and the restrictions it placed on the royal executive. However, Mikkelsen then stated, the charter was no just legal document and its stipulations therefore void since “...

the council of Denmark’s realm cannot document their right to election other than to the time after Queen Margaret’s death: In all chronicles before her, the succession is no different than being hereditary.”

[12]

The cause of the political impasse, indeed the very cause of the “poisoned time” had, in the king’s mind, to be found in this deviation from the God-given, natural order of government. Peace and stability did therefore not hinge on a return to the tried and failed system of the monarchia mixta, but rather depended on “...

such a state of governance,

[13] and God’s word, amongst the people, who teach them how to obey their authorities in honour and devotion, then - without a doubt - will in Denmark be a long lasting peace and harmonious love.”

[14]

By all accounts, the entire council hall held its breath as the king’s burgher enforcer directly addressed his sovereign, imploring him to “...

on the welfare of Your Grace and Your Grace’s children and that of all Danishmen to receive the realm as a hereditary monarch and as such a prince act with grace and mercy.”

[15]

Rising from his seat, Christian II in turn asked his chief commanders if they would be prepared to defend his rights as a hereditary monarch. In response all four knelt, drew their swords and placed them at their sovereign’s feet. At this show of fealty some of those present broke into cheers, but Bryske and Beldenak defiantly began to protest the legality of the proceedings, being joined by a large amount of their followers. Immediately thereafter, the doors to the council hall swung open and a troop of men-at-arms entered, seized the two prominent council-constitutionalists and dragged them from the room.

As the scuffle died down, it was Mogens Gøye’s turn to rise and proclaim to the assembly that “...

he who will concur with his royal majesty and the above councillors of war, shall have his safety assured, but he who will not, he shall also be seized.” Supposedly, Henrik Gøye, the Steward of the Realm’s younger brother, then quipped to the king that he thought that the other delegates “...

would after all quite willingly kiss the rod.”

[16]

Apocryphal or not, the statement made by the younger Gøye proved to be correct. When Christiern Pedersen also rose and promised the undying fidelity of the Danish church, the remaining opposition quite simply folded in on itself. Emerging from the episcopal palace, the king proceeded to Viborg’s Cathedral square, where the remaining delegates of the Estates had been summoned. The archbishop now declared that the council of the realm had offered the king to receive the crown as a hereditary monarch and granted him provision to create “...

a lasting and loveable concordant and just governance that might solve this difficult time and advance, defend and exalt the realm of Denmark in perpetuity.”

In the modern literature there has been a tendency to portray the “

altercation of state” of 1523 as a prime example of “...

a conventional alliance between prince and pleb.” Still, such a reading ignores the fact that the altercation happened with the blessing of the most senior members of both the Lords Temporal and Spiritual. Without the crucial support of Mogens Gøye and the church, the king would simply not have had the political muscle needed to force through his dearest ambition - the destruction of the councilar restraints on the crown and the Oldenburg dynasty.

Besides, to contemporaries, hereditary monarchy did not necessarily mean absolute monarchy. It is quite evident that Mogens Gøye and his confederates fully expected to continue to play an important part in the governance of the realm. In this regard, the Viborg Altercation suddenly appears as a far less radical break with tradition.

Nevertheless, as Christian II accepted the acclamation of a thousand delegates, their right hands raised in homage, there could be little doubt as to who ruled the realm. In the subservient words of Matthias Gabler, the king received his unbound crown as “...

a Hyperborean Constantine, shining bright with the image of threefold scepters, shadowing the names and deeds of other princes.”

[17]

Footnotes:

[1]From an OTL 1521 poem in Latin by Gabler titled “

Matthias Gabler Greets the Marvelous Christernus, the Danes’ Famous and Invincible King”

[2]Known in Danish as Hærvejen and in German as the Ochsenweg, the Oxen Road was the primary overland trade artery of the Jutland peninsula.

[3]The term Estates General is my own rendering of the Danish political institution of stændermøde (literally Meeting of the Estates). Up until this point, the Estates General was very rarely called and only so, when one of the parties to governance (crown or nobility) sought to legitimise certain, and often controversial political propositions. It was also a rather large event. At the OTL meeting in 1536 some 1200 people showed up.

[4]Quote from Poul Helgesen’s 1534 chronicle, originally referring to the spread of Lutheranism from Viborg.

[5]From an OTL statement made by the representatives of the lower gentry during the accession charter negotiations of 1513. The original transcript reads: “...

at Danmarckis rigæ ær it frit kaare riigæ, oc hwad anfalldt eller feide som kommer paa Danmarckis riigæ, tha ære wii thee som thet skall affwerie…”

[6]In contemporary sources only nobles were referred to as being free (i.e. free from taxation). Commoners and peasants were all, conversely, considered to have been born unfree - tied to the jurisdiction and protection of their betters.

[7]The same term was applied to the taxes levied by Frederick I in 1524, which immediately resulted in a peasant rising in Scania.

[8]A slightly rewritten quote by Christian II from 1520 where he noted that the campaign against Sten Sture had not been won thanks to the Swedes, but in the face of their opposition.

[9]As mentioned in Chapter 15, he had suggested burning rebel towns to the ground.

[10]Jens Andersen Beldenak was an eminent scholar of the law - especially canonical law. In OTL he had an even more tumultuous relationship with the king and spent several years imprisoned under harsh conditions. Still, he was brought to Sweden after the surrender of Stockholm and was the main legal expert who “proved” that Sweden had always been a hereditary monarchy. He also presided over the ecclesiastical court that convicted the pardoned Sture rebels of heresy, thereby giving the Stockholm Bloodbath a thin veneer of legality.

[11]A slightly rewritten OTL quote from 1536 used to describe the arrest and deposition of the Catholic bishops by Christian III.

[12]From a letter to Christian II from Hans Mikkelsen, dated 10/8 1526. The original reads: “...

aldring kand Danmarcks riiges raad lengere proscribere theres vtuellelsse end siden dronning Margretes död; alle krönicker fore henne findes thet icke anderledes end til arff...”

[13]I.e. the hereditary monarchy.

[14]From the same letter. The original reads: “…

thet soo kommer vti sijn stadt igen, och guds ord kommer eblandt folcket, som lerer thennom, huorledes thee skulle holle theres offuerighed vti ere oc elsskelighed, thaa vden ald twiffwel bliffuer vti Danmarck en languoverende friid och endrechtig kerlighet.”

[15]Ibid. Slightly rewritten and condensed. The original reads: “…

paa ethers nades oc börns lange bestand og velffartter, sammeledes alle dansskemends, at ethers nade [...] anammer riiget ighen som en arff konge, och thennom, som sodant ville göre at beuise nade och barmhertighet.”

[16]Both this quote and the one above made by Mogens Gøye are taken from an OTL report written by the admiral Johann von Pein to his master, Albert duke of Prussia, detailing the events surrounding the arrest of the Danish Catholic bishops in 1536.

[17]An amalgamation of various verses from the poem referred to in footnote 1.