Thinking about it Burnside was often more in his element as an engineer than the commander of manoeuvre army. Alas the British may be playing to his strengths. (Americans are of course allowed to yay at this).

YAY!!

Thinking about it Burnside was often more in his element as an engineer than the commander of manoeuvre army. Alas the British may be playing to his strengths. (Americans are of course allowed to yay at this).

If the British do stop at any line of earthworks because they run low on manpower, what is preventing them from perhaps digging in at another point for a while? In a race against time, the Americans do still have more to lose. I thought they cannot as of yet replenish their ammunition supplies as fast as they are spending them? And the economy is teetering on the brink of freefall?

Minor question/quibble: what’s your source for General William F Williams’ middle name being Frederick? I always understood it was William Fenwick Williams.

Two chapters ago.Shoot, you're definitely right that it is supposed to be William Fenwick Williams. Where did I put the wrong name down so I can fix that?

Two chapters ago.

Secret Finnish Defence Plans

What? You sure you in the right thread?Technology Plan

Sorry, i make a huge mistake.

I posted in the wrong place, sorry for this.

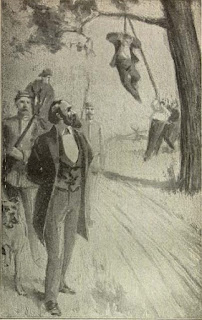

Ha, Denison is such a wonderful character. I hope he does well in the war.

It occurs to me that somewhere in this chaos, Harry Flashman is having a hell of an adventure.

Sorry, i make a huge mistake.

I posted in the wrong place, sorry for this.

Too limiting, Harry would have a place with each of the three combatants as a spy, soldier and cad.Ah but where to put him? He'd probably get along well with Field Marshal Dundas (who from all I've been able to find out about him says he was a salacious gossip), but there he'd be smack dab in the middle of the worst fighting. Charging against old Hancock in the defense of Portland? Or maybe he's off having a good time in New Zealand as things are getting more upset in 1863!

Too limiting, Harry would have a place with each of the three combatants as a spy, soldier and cad.

So tempting to actually suggest ideas for an OTL fiction character to show up in your TL that is trying to be historically and logically true.