Book I - America in Waiting: The Remainder of Nixon's Term

Chapter IV

To The Finish

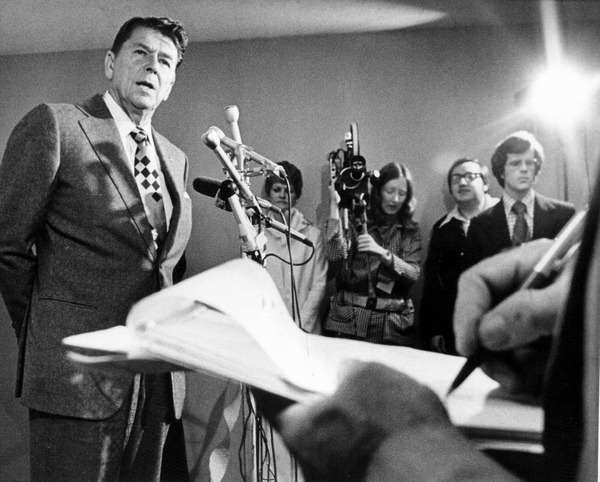

As janitors and crew swept up the fallen confetti and popped the remaining balloons in Kansas City, Senator Jesse Helms awoke with a new mission. He may have just cost Ronald Reagan the Republican nomination (though he tended to think he didn’t), but at least he had not compromised on his principles. Reagan, in his eyes, was weak and ineffectual. If you weren’t willing to stick to the conservative platform, you had no place leading the conservative movement. John Sears, Reagan’s campaign manager, agreed to come on as Helms’ campaign manager. Immediately, they would need to get to work on securing ballot access in as many states as possible. They had little time, but Helms’ extensive donor list enabled them to raise the money needed to hire canvassers to get the needed signatures. Helms announced his running mate, Maryland Congressman Bob Bauman, two days after the Republican National Convention.

Ronald Reagan returned to California dejected and confused. He had gone from nearly becoming the Republican nominee to thoroughly unsure of his role within the Republican Party. He as tempted to endorse Helms and campaign for him, but if Reagan wanted to win the Republican nomination in 1980, he would need to be a Party man. He endorsed Rockefeller, only further angering Helms. Largely, though, Reagan faded from the national spotlight, awaiting a chance to return should Rockefeller lose the election.

The Rockefeller campaign was thrilled by Helms’ entrance. In fact, Rockefeller sent volunteers to help Helms get on the ballot in Southern states where he believed Helms would draw supporters away from the regional candidate, Democrat Jimmy Carter. In many ways, Carter was a more conservative candidate than Rockefeller. The president hoped to exploit Helms’ candidacy to his advantage by tying Carter and Helms together ideologically, giving him room for half of the middle and the left. In fact, some Democratic lawmakers privately confessed they were considering voting for Rockefeller.

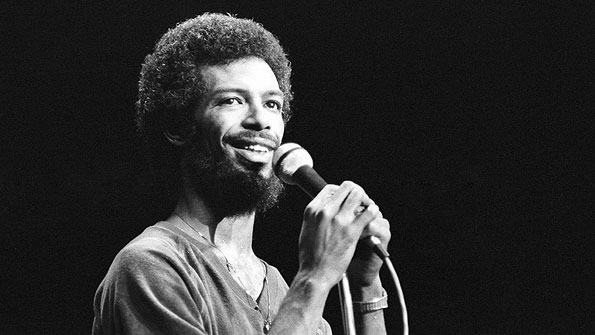

Democrat Jimmy Carter campaigning for the White House in 1976.

The 1976 campaign was significant for this very reason. Neither candidate neatly fit into the ideological boundaries of their time. Carter, a Southerner, was part of the New South, but still attended a segregated church. Rockefeller, a liberal Republican, was of a dying breed. In fact, it was likely that he would be the last moderate Republican nominated, but if he were elected in November, it was possible that the moderates might return to the Republican Party and the New Right could form their own party or rejoin the Democrats. The future of it all was very uncertain. Those questions would be left to political scientists and historians, however. In the meantime, there was a three-way race for the presidency.

The Rockefeller/Dole ticket again emphasized Rockefeller’s stable leadership and the need for the White House to remain in trusted hands. Rockefeller had been around for decades. The American people knew him and could trust him. He’d run the Rockefeller Commission to bring transparency to government in the wake of Watergate. Carter was an unknown. His candidacy began with the question of, “Jimmy who?” and many Americans still didn’t know him by the time the general election campaign kicked off. Though some Americans, still reeling from Watergate, thought the country needed a fresh start, many more were convinced that after the resignation of one president and the assassination of another, it was time to project strength from the Oval Office. Rockefeller certainly did that. It would be tough to overstate how much the assassination of Gerald Ford shocked the American psyche. It was the fourth high profile political assassination in ten years. For many, it brought back the images of Robert Kennedy, bleeding on the kitchen floor of Los Angele’s Ambassador Hotel. Carter appealed on the basis of a new start – a chance to put that history behind them. Rockefeller appealed to voters because he was someone they could trust to do the job and halt the instability gripping the nation. Jesse Helms was just too radical for most voters outside of the South.

For much of September, the race progressed without incident. Carter’s running mate Walter Mondale hit Rockefeller for moving to the right. Most voters found the attempts to label Rockefeller as too conservative laughable. After all, conservatives literally created a third party to challenge Rockefeller. The Rockefeller campaign stayed on message almost painfully. Every campaign ad, every stump speech, and every interview answer seemed to say the same thing: When America needed a leader; Nelson Rockefeller stepped up to the plate. Plus, Carter’s Watergate message was falling short. Without criticizing the pardon of Nixon (which could not be connected to Rockefeller), Carter just seemed to be emphasizing his peanut farm. The Republican Party, with Rockefeller at the helm, was sufficiently distanced from Watergate.

Senator Jesse Helms ran for the presidency as an independent; he was the most conservative candidate in the race.

In early October, Rockefeller led and Carter felt it was time to drift from his comfort zone. He sat for an interview in

Playboy where he committed one of the greatest gaffes in presidential politics. Asked about his views on sin, Carter replied that he had “committed adultery in my heart many times.” And confessed he looked at many women with lust. Somehow Jimmy Carter managed to the morality argument to a man who divorced his first wife so he could marry his mistress. Carter’s campaign staff was distraught. Hamilton Jordan, the campaign manager, remarked how “only Carter” could think talking about lust in

Playboy magazine would win him votes. “The most religious candidate of our generation,” Jordan said in disbelief, “somehow lost on the question of morality to a serial cheater. Un-fucking-believable. Actually, I take that back. Not with Jimmy.”

Unfortunately for Carter, the candidates were unable to come to an agreement on any televised debates, which may have given Carter the platform to come back. Neither side particularly wanted them. Carter’s staff thought he would do poorly against the more polished Rockefeller. The Republicans didn’t want to put Carter on equal footing as the president. Helms, for his part, demanded a national debate, but while Carter himself wanted to debate Helms, his staff said that the image of Carter on stage with a third party candidate and without Rockefeller would diminish his standing against Rockefeller. “It’ll look like the kids are running amok while Rockefeller is the only responsible candidate,” Jordan explained.

While Carter himself wanted to debate Rockefeller, his campaign team worried about how he'd do against the president.

The polls indicated that the national popular vote was anyone’s for the taking and when voting ended on Election Day, neither side was sure who would come out on top. Early on, everyone realized it was going to be a close fight. The percentage of the vote Helms was able to land would prove key in several states. Rather quickly, Helms was declared the winner of his native North Carolina, taking 13 electoral votes away from the Democrats who were widely expected to carry the South. Rockefeller took most of the Northeast, including his home state of New York. Carter, however, was able to hold on to Massachusetts and Rhode Island, states that wouldn’t budge from the Democratic column no matter how liberal the Republican was. He also managed to take Maine where his outsider image and Southern charm proved more relatable than Rockefeller’s penthouse appeal.

Reporters quickly identified the closest states of the night: Pennsylvania, Ohio, Texas, and California – a combined 123 electoral votes that had the ability to decide the election. Carter would likely need all of them to win the election given Helms scored electoral victories in Arkansas, Mississippi, and South Carolina (21 electoral votes that would have afforded Carter the ability to lose Ohio or Pennsylvania). At the White House, Rockefeller looked with horror as Texas and its 26 electoral votes were called for Carter. Of course, no Democrat in recent memory had ever made it to the White House without Texas. It was more important for Democrats than it was for Republicans.

Without Texas, however, Oregon’s six electoral votes were more important. Rockefeller sat at 211 electoral votes and Carter had 190. Carter had to win California’s 45 electoral votes in order to have a chance. He would need at least Pennsylvania and Ohio to win the election. Rockefeller could afford to lose Oregon but not both Pennsylvania and Ohio if he lost California. The nightmare scenario would be for no candidate to reach 270. If either candidate won California, but not some combination of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Oregon, the election would go to the House to decide the president and the Senate to decide the vice president. Neither Carter nor Rockefeller wanted that outcome.

When the networks called Ohio for Rockefeller, it helped dampen some of that concern. Then, Barbara Walters broke in with an important announcement on ABC News. “We can now call California, and the presidency, for President Nelson Rockefeller.” The president went on to win Pennsylvania and Oregon. Carter, for his part, did reasonably well. Helms drew rather evenly from both sides, but some speculated that had he not been on the ballot in California those Reagan Republican votes could have broken for Carter as opposed to Rockefeller. Perhaps they, with enough votes in Ohio or Pennsylvania, could have tipped the presidency. Helms didn’t give a damn. He was no more upset that Rockefeller had won than he would’ve been had Carter won. In his eyes, the whole election was an enormous waste of time.

President Nelson Rockefeller and the First Lady, Happy, at Rockefeller's victory party on Election Night 1976.

Carter delivered a gracious concession speech in which he called on the country to unite as it did 200 years earlier at the founding of the nation. “Like our revolutionary heroes before us, we march into this third century for our country with hope and optimism – determined to do all we can as Americans to leave a better nation for our posterity.” The next morning, Rockefeller held a press conference at the White House where he thanked Carter for his words and invited him to the White House for a discussion. It was the first time the candidates would formally meet.

Right away, Rockefeller began working on his new administration. He hoped to push forward major energy legislation, which became a topic of discussion with Carter during the governor’s visit. He also wanted to replace some of the cabinet holdovers with his new people. Bush and Clements would stay on. Cheney, back from the campaign, nabbed a role as the Director of the Office of Management and Budget. Rockefeller asked Lowell Weicker of Connecticut to join his administration as the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, but Weicker expressed a desire to remain in the Senate. Rockefeller decided to appoint former Michigan Governor George Romney to the position.

United States Presidential Election, 1976

Nelson A. Rockefeller/Robert Dole (R) ... 314 electoral votes ... 46.6% of the popular vote

James E. Carter/Walter F. Mondale (D) ... 190 electoral votes ... 43.5% of the popular vote

Jesse Helms/Robert E. Bauman (I) ... 34 electoral votes ... 9.9% of the popular vote

United States Senate Elections, 1976

Arizona: Dennis DeConcini, D def. Sam Steiger, R. (D+1)

California: S.I. Hayakawa, R def. Sen. John V. Tunney, D. (R+1)

Connecticut: Sen. Lowell P. Weicker, R def. Gloria Schaffer, D.

Delaware: Sen. William V. Roth, Jr., R def. Thomas C. Maloney, D.

Florida: Sen. Lawton Chiles, D def. John Grady, R.

Hawaii: Spark Matsunaga, D def. William F. Quinn, R. (D+1)

Indiana: Sen. Richard Lugar, R def. Sen. Vance Hartke, D. (R+1)

Maine: Sen. Edmund Muskie, D def. Robert Monks, R.

Maryland: Paul Sarbanes, D def. Sen. John Glenn Beall, Jr., R. (D+1)

Massachusetts: Sen. Ted Kennedy, D def. Michael Robertson, R.

Michigan: Philip Hart, D def. Marvin L. Esch, R.

Minnesota: Sen. Hubert Humphrey, D def. Gerald Brekke, R.

Mississippi: Sen. John C. Stennis, D reelected without opposition.

Missouri: John Danforth, R def. Warren E. Hearnes, D. (R+1)

Montana: John Melcher, D def. Stanley C. Burger, R.

Nebraska: Edward Zorinsky, D def. John McCollister, R. (D+1)

Nevada: Sen. Howard Cannon, D def. David Towell, R.

New Jersey: Sen. Harrison A. Williams, D def. David A. Norcross, R.

New Mexico: Harrison Scmitt, R def. Sen. Joseph Montoya, D. (R+1)

New York: Bell Abzug, D def. Sen. James Buckley, R. (D+1)

North Dakota: Sen. Quentin N. Burdick, D def. Robert Stroup, R.

Ohio: Sen. Robert Taft, Jr., R def. Howard Metzenbaum, D.

Pennsylvania: H. John Heinz III, R def. William J. Green III, D.

Rhode Island: John Chafee, R def. Richard Lorber, D. (R+1)

Tennessee: Jim Sasser, D def. Sen. Bill Brock, R. (D+1)

Texas: Sen. Lloyd Bentsen, D def. Alan Steelman, R.

Utah: Orrin Hatch, R def. Sen. Frank Moss, D. (R+1)

Vermont: Sen. Robert Stafford, R def. Thomas P. Salmon, D.

Virginia: Harry F. Byrd, I def. Elmo Zumwalt, Jr., D.

Washington: Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson, D def. George Brown, R.

West Virginia: Sen. Robert Byrd, D reelected without opposition.

Wisconsin: Sen. William Proxmire, D def. Stanley York, R.

Wyoming: Malcolm Wallop, R def. Gale W. McGee, D. (R+1)

Senate composition before election: 61 D, 37 R, 1 Ind. Democrat, 1 Conservative

Senate composition after election: 60 D, 39 R, 1 Ind. Democrat

Senate Majority Leader: Robert Byrd (D-WV)

Senate Majority Whip: Alan Cranston (D-CA)

Senate Minority Leader: Howard Baker (R-TN)

Senate Minority Whip: Ted Stevens (R-AK)

United States House of Representatives Elections, 1976

House composition before election: 291 D, 144 R

House composition after election: 290 D, 145 R (R+1)

Speaker of the House: Tip O’Neill (D-MA)

House Majority Leader: Richard Bolling (D-MO)

House Majority Whip: John Brademas (D-IN)

House Minority Leader: John Rhodes (R-AZ)

House Minority Whip: Robert Michel (R-IL)

United States Gubernatorial Elecitons, 1975

Kentucky: Gov. Julian Carroll, D def. Bob Gable, R.

Louisiana: Gov. Edwin Edwards, D def. Robert G. Jones, D.

Mississippi: Cliff Finch, D def. Gil Carmichael, R.

Governors before election: 36 D, 13 R

Governors after election: 36 D, 13 R

United States Gubernatorial Elections, 1976

Arkansas: Gov. David Pryor, D def. Leon Griffith, R.

Delaware: Pierre S. du Pont IV, R def. Gov. Sherman W. Tribbitt, D. (R+1)

Illinois: James R. Thompson, R def. Michael Howlett, D. (R+1)

Indiana: Gov. Otis Bowen, R def. Larry Conrad, D.

Missouri: Joseph P. Teasdale, D def. Gov. Kit Bond, R. (D+1)

Montana: Gov. Thomas Lee Judge, D def. Robert Woodahl, R.

New Hampshire: Gov. Meldrim Thomson, Jr, R def. Harry Spanos, D.

North Carolina: Jim Hunt, D def. David Flaherty, R. (D+1)

North Dakota: Arthur A. Link, D def. Richard Elkin, R.

Rhode Island: John Garrahy, D def. James Taft, R.

Utah: Scott M. Matheson, D def. Vernon Romney, R.

Vermont: Richard Snelling, R def. Stella Hackel, D. (R+1)

Washington: Dixy Lee Ray, D def. John Spellman, R. (D+1)

West Virginia: Jay Rockefeller, D def. Cecil Underwood, R. (D+1)

Governors before election: 36 D, 13 R

Governors after election: 37 D, 12 R

Cabinet of President Nelson Rockefeller

President: Nelson Rockefeller (1975- )

Vice President: Bob Dole (1975- )

Secretary of State: George H.W. Bush (1975- )

Secretary of Treasury: William E. Simon (1974- )

Secretary of Defense: Bill Clements (1975- )

Attorney General: Edward H. Levi (1975- )

Secretary of the Interior: Thomas S. Kleppe (1975- )

Secretary of Agriculture: John Albert Knebel (1976- )

Secretary of Commerce: Elliot Richardson (1975- )

Secretary of Labor: William Usery Jr. (1976- )

Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare: George W. Romney (1977- )

Secretary of Housing and Urban Development: Carla Anderson Hills (1975- )

Secretary of Transportation: William Thaddeus Coleman Jr. (1975- )

White House Chief of Staff: George Hinman (1975- )

Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency: Russell Train (1974- )

Director of the Office of Management and Budget: Dick Cheney (1977- )

U.S. Trade Ambassador: Frederick B. Dent (1975- )

U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations: William Scranton (1976- )