You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Land of Sweetness: A Pre-Columbian Timeline

- Thread starter Every Grass in Java

- Start date

-

- Tags

- mesoamerica mesoamerican taino

Threadmarks

View all 86 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Entry 58: The Death of Lord Mahpilhuēyac Entry 59: The Fall of Lyobaa, August 1410 Entry 60: The Fingers' Children Entry 61: The Death of Lord Tlamahpilhuiani, 1411 Entry 62: The Cholōltec War, 1411—1413 Entry 63: Ah Ek Lemba's Oration at Cempoala, 1413 Entry 64: Responding to Defeat, 1413 Entry 64-1: Chīmalpāin's NameOasisamerica seems to be forming into the inverse mirror of Mesoamerica; egalitarian, non-violent, and much less warfare-focused. Thank goodness Ah Ek Lamba won't be stomping around in the region!

But that makes them more vulnerable when the europeans arrive.Oasisamerica seems to be forming into the inverse mirror of Mesoamerica; egalitarian, non-violent, and much less warfare-focused. Thank goodness Ah Ek Lamba won't be stomping around in the region!

oh the diseases and I suspect diseases will wipe them out as otlBut that makes them more vulnerable when the europeans arrive.

I mean in terms of social and military resistence, right now they are protected only by their geography.oh the diseases and I suspect diseases will wipe them out as otl

I am under the impression that societal resistance to Europeans by the Pueblo peoples IOTL was fairly decent, by the standards of the utterly apocalyptic scenario that, IOTL, all Native peoples of the Americas, bar none, experienced after the Columbian Exchange. More militarily equipped peoples fared generally no better. A resilient society (resilience being arguably helped by the egalitarian outlook) and a protective geography were what "protected" the Puebloan peoples (as in, they were "only" devastated and expropriated, as opposed to the utterly brutal mix of extermination, extreme subjugation and almost total deculturation of the survivors that was fairly common fare in many parts of the Americas). Being militaristic (in the way the Mexica were, let's say) would not have done them much good facing determined European effort to put them down (as Mesoamerica, the Andes and plenty other situation does indeed show, though I suppose that the Mapuche can be taken as a partial counterexample).I mean in terms of social and military resistence, right now they are protected only by their geography.

This isn't really relevant to Oasisamerica, but it's something that came to mind when I was writing the examples of stylized Hopi script in the most recent entry. This was said before a long, long time ago in Entry 10, but I felt it was worth reiterating in stronger terms.

One of the key ways Oasisamerica is unlike Mesoamerica is that the former's elite prefers a writing system. By "writing system," I mean that they have a system that can encode language exactly. Hopi, for example, is written in a 127-character, 20-diacritic syllabary (TTL's "Standard Hopi" has twenty consonants and six vowels, and final consonants are written with diacritics).

The origin of the Oasisamerican syllabary is Mesoamerica's "merchants' script," whose characters derive from a simplification of the syllabic values of Maya hieroglyphs. The merchants' script is also a syllabary, and it has a few different variants. The most widely used one is the one for Nahuatl (Isatian), which has 60 different characters corresponding to the sixty combinations you can make from the fourteen possible initial consonants (plus no initial consonant) and four vowels of Nahuatl. With a diacritic to mark long vowels and special diacritic forms of the fourteen final consonants, you can write all of the 1,680 syllables that Nahuatl phonology permits.

(I've invented two sets of glyphs for TTL's Nahuatl syllabary. The first is more primitive. It uses a lot of ugly boxes that are simplified forms of Maya face glyphs, long vowels are marked by doubling vowel characters instead of using a diacritic, and there aren't special characters for final consonants; a word like calli is written ca-li-li. You can see how it looks like in Page 10.)

(The second is a lot more elegant and easier to write with the brush pen used by Mesoamerican scripts, mainly because I was inspired by China, the other brush-using civilization, and got rid of all the boxes and replaced them with "hats" resembling the Chinese radical 人. Doubled vowels and syllabic characters representing final consonants also went the way of the dodo as diacritics were introduced.)

But the merchant's script is low-prestige. It's easy and quick to write, so merchants use it for commercial purposes ("bring me twenty turkeys tonight"), generals use it to give orders, and so forth. But because it's perceived as almost blasphemously easy to write, it's not used for literature.

In fact, TTL's Mesoamerican literature doesn't use a writing system at all. What it has is a semasiographic system, which encodes meaning, not a specific spoken language. Familiar examples include musical notation or OTL's Aztec pictographs. But it's not just any semasiographic system; it's one that's more complete, as in "capable of expressing the full range of human ideas, not just classical music," than any semasiography used IOTL. I'm not sure to what degree it's plausible, but I really like the concept.

Say that a TTL Mesoamerican opens a codex and sees a painting of a peasant kneeling before a lord. There's a speech scroll covered with feathers issuing from the mouth of the peasant, and the scroll unfolds into a box above the peasant. Everything so far is written in black ink. Within the box, there's a sleeping peasant (drawn in blue ink), and another box issuing from his chest. In this second box, there's the same peasant kneeling before the same lord, only drawn in red ink.

In the same way that we can "read" non-written elements of a comic book (e.g. a speech bubble means that the person is speaking; a thought bubble means the person is thinking; a certain jagged yellow shape means an explosion), TTL's Mesoamerican can "read" this painting with no ambiguity.

But the basic elements of the translation would be the same for all readers. For example, nobody could translate this as the peasant "shouting," because shouting would require the speech scroll to have thicker lines than was actually used. Nor could anybody think that the peasant was saying "I met you in my dreams," because the dream was in red ink, so the peasant dreamed it as a future event (hence "would").

More details drawn on the picture would further qualify the description and limit the range of possible interpretations, just as with spoken language.

This is what Mesoamerican elites use and what almost all the primary sources quoted in almost all prior entries are written in. Historians learn the conventions of the system if they want to major in the field.

(OTL Mesoamerica had something similar, but there was something missing—grammatical elements. OTL Aztec codices don't explicitly spell out the relative position in time of specific events, as TTL's system does with color, nor does it mark recursion, as TTL's system does with dozens of different types of boxes and lines. The result is that the OTL system is a lot more context-dependent than TTL's. OTL Aztec pictographs is to TTL's semasiographic system almost as hand gestures is to sign language.)

One of the key ways Oasisamerica is unlike Mesoamerica is that the former's elite prefers a writing system. By "writing system," I mean that they have a system that can encode language exactly. Hopi, for example, is written in a 127-character, 20-diacritic syllabary (TTL's "Standard Hopi" has twenty consonants and six vowels, and final consonants are written with diacritics).

The origin of the Oasisamerican syllabary is Mesoamerica's "merchants' script," whose characters derive from a simplification of the syllabic values of Maya hieroglyphs. The merchants' script is also a syllabary, and it has a few different variants. The most widely used one is the one for Nahuatl (Isatian), which has 60 different characters corresponding to the sixty combinations you can make from the fourteen possible initial consonants (plus no initial consonant) and four vowels of Nahuatl. With a diacritic to mark long vowels and special diacritic forms of the fourteen final consonants, you can write all of the 1,680 syllables that Nahuatl phonology permits.

(I've invented two sets of glyphs for TTL's Nahuatl syllabary. The first is more primitive. It uses a lot of ugly boxes that are simplified forms of Maya face glyphs, long vowels are marked by doubling vowel characters instead of using a diacritic, and there aren't special characters for final consonants; a word like calli is written ca-li-li. You can see how it looks like in Page 10.)

(The second is a lot more elegant and easier to write with the brush pen used by Mesoamerican scripts, mainly because I was inspired by China, the other brush-using civilization, and got rid of all the boxes and replaced them with "hats" resembling the Chinese radical 人. Doubled vowels and syllabic characters representing final consonants also went the way of the dodo as diacritics were introduced.)

But the merchant's script is low-prestige. It's easy and quick to write, so merchants use it for commercial purposes ("bring me twenty turkeys tonight"), generals use it to give orders, and so forth. But because it's perceived as almost blasphemously easy to write, it's not used for literature.

In fact, TTL's Mesoamerican literature doesn't use a writing system at all. What it has is a semasiographic system, which encodes meaning, not a specific spoken language. Familiar examples include musical notation or OTL's Aztec pictographs. But it's not just any semasiographic system; it's one that's more complete, as in "capable of expressing the full range of human ideas, not just classical music," than any semasiography used IOTL. I'm not sure to what degree it's plausible, but I really like the concept.

Say that a TTL Mesoamerican opens a codex and sees a painting of a peasant kneeling before a lord. There's a speech scroll covered with feathers issuing from the mouth of the peasant, and the scroll unfolds into a box above the peasant. Everything so far is written in black ink. Within the box, there's a sleeping peasant (drawn in blue ink), and another box issuing from his chest. In this second box, there's the same peasant kneeling before the same lord, only drawn in red ink.

In the same way that we can "read" non-written elements of a comic book (e.g. a speech bubble means that the person is speaking; a thought bubble means the person is thinking; a certain jagged yellow shape means an explosion), TTL's Mesoamerican can "read" this painting with no ambiguity.

- The speech scroll means the peasant is speaking, and the feathers means that his speech is courteous.

- The things within the box that the scroll opens into are the contents of the man's speech.

- The use of blue ink means that it's a past event.

- A box issuing from the chest of a sleeping person refers to a dream. The things within the box are the contents of the dream.

- Red ink means that it's a future event.

The peasant knelt before the lord. He said: "Your honored lordship, I dreamed that I would meet you."

Of course, each reader would have a slightly different interpretation. Someone else might translate the painting as:

The peasant prostrated before the lord, saying: "Sir, I knew that I would meet you from my dreams."

But the basic elements of the translation would be the same for all readers. For example, nobody could translate this as the peasant "shouting," because shouting would require the speech scroll to have thicker lines than was actually used. Nor could anybody think that the peasant was saying "I met you in my dreams," because the dream was in red ink, so the peasant dreamed it as a future event (hence "would").

More details drawn on the picture would further qualify the description and limit the range of possible interpretations, just as with spoken language.

This is what Mesoamerican elites use and what almost all the primary sources quoted in almost all prior entries are written in. Historians learn the conventions of the system if they want to major in the field.

(OTL Mesoamerica had something similar, but there was something missing—grammatical elements. OTL Aztec codices don't explicitly spell out the relative position in time of specific events, as TTL's system does with color, nor does it mark recursion, as TTL's system does with dozens of different types of boxes and lines. The result is that the OTL system is a lot more context-dependent than TTL's. OTL Aztec pictographs is to TTL's semasiographic system almost as hand gestures is to sign language.)

Last edited:

The Mexico got so unlucky it unbelievable it would have been much much harder for them to conquer them if the spanish didn't roll 13s and I do not remember the name but a native American stop us expansion across the Mississipi... comaches not sure I might be mistaken about bot .. native Americans almost stop us expansion in the beginning. also the Pacifica northwest was peaceful but there was nothing left when we arrivedI am under the impression that societal resistance to Europeans by the Pueblo peoples IOTL was fairly decent, by the standards of the utterly apocalyptic scenario that, IOTL, all Native peoples of the Americas, bar none, experienced after the Columbian Exchange. More militarily equipped peoples fared generally no better. A resilient society (resilience being arguably helped by the egalitarian outlook) and a protective geography were what "protected" the Puebloan peoples (as in, they were "only" devastated and expropriated, as opposed to the utterly brutal mix of extermination, extreme subjugation and almost total deculturation of the survivors that was fairly common fare in many parts of the Americas). Being militaristic (in the way the Mexica were, let's say) would not have done them much good facing determined European effort to put them down (as Mesoamerica, the Andes and plenty other situation does indeed show, though I suppose that the Mapuche can be taken as a partial counterexample).

Last edited:

I mean, the Pueblos did have several revolts against the Spanish and one in 1681(the Pueblo Revolt, aka Pope's Rebellion) drove the Spanish out for a decade. I think it does matter as much that the Pueblos were on the fringes of Spanish North America, and according to this book the threat of revolt(at least in the "we can't afford another one of these" forced the Spanish to be more accommodating of Pueblo customs and more willing to make concessions to their interests.

Yah but were they a peaceful society or did they become militaristic too fight against them too?I mean, the Pueblos did have several revolts against the Spanish and one in 1681(the Pueblo Revolt, aka Pope's Rebellion) drove the Spanish out for a decade. I think it does matter as much that the Pueblos were on the fringes of Spanish North America, and according to this book the threat of revolt(at least in the "we can't afford another one of these" forced the Spanish to be more accommodating of Pueblo customs and more willing to make concessions to their interests.

No. It's important to remember that the system is entirely detached from the phonology of Nahuatl/Otomi/Mixtec/Zapotec/Maya/whatever. Even names are "written" according to their semantic value, i.e. what the name means. Writing represents spoken language in visual form. This semasiographic system is really a visual language in itself. And just as you can write down English iambic pentameter but it's impossible to translate it into French without sacrificing the meter, it's impossible to translate the vagaries of spoken language into the Mesoamerican system.I wonder if you translate aspects of verse-stress, rythm, etc.

Speech scrolls can be modified with certain visual elements to specify that the person is speaking in verse or singing, but that's equivalent to spoken-language expressions like "say poetically" or "speak in verse," not the actual rhythm of the verse.

As this is a visual system, the equivalent to the verse literature of Mesoamericans' spoken languages is a painting executed to high artistic standards. (But because the very point of scorning the syllabary and using this unwieldy system is because of its universality and beauty, and since semasiographic works are almost all commissioned by rulers and executed by teams of professional artists, it's a given that almost all codices are exceptionally beautiful.)

Song lyrics for entertainers and such are probably written in merchants' script.

* * *

Also, would there be an interest in me sketching out the "grammatical" elements of the semasiographic system? I imagine that, even though it doesn't encode language directly, what kind of contextual information (the relative position in time of different scenes in the picture, etc.) is explicitly marked by the picture would still be heavily affected by the spoken language. For example, a Mixtec-based semasiography will probably only obligatorily mark past, present, and future because that's what Mixtec verbs do. But a Mayan-based semasiography is more likely to distinguish between scenes that took place in the recent past and ones that took place in the distant past, because that's what Mayan verbs do.

By reading up on the grammatical systems of Nahuatl, Mixtec, and Yucatec Maya (the three most important languages in Mesoamerica, excluding Tarascan) and the conventions of OTL Mesoamerican pictographs, I could probably sketch a semi-plausible series of "grammatical conventions" for the semasiography.

Pros:

- Helps in worldbuilding, and I really like the idea of a not-really-writing system that took things the other way, encoding meaning instead of sounds.

- Maybe I'll have a coherent system to draw stuff for future entries, even if I really am not much of an artist.

Cons:

- Takes time (a few days?), further delaying the chronological progression of the TL (and the arrival of the Europeans, which a lot of people seem to be anticipating)

Thoughts? I'll set up a poll.

Dont worry about time, this is the fastest updating timeline I am following dispate the quality and complexity of the content.No. It's important to remember that the system is entirely detached from the phonology of Nahuatl/Otomi/Mixtec/Zapotec/Maya/whatever. Even names are "written" according to their semantic value, i.e. what the name means. Writing represents spoken language in visual form. This semasiographic system is really a visual language in itself. And just as you can write down English iambic pentameter but it's impossible to translate it into French without sacrificing the meter, it's impossible to translate the vagaries of spoken language into the Mesoamerican system.

Speech scrolls can be modified with certain visual elements to specify that the person is speaking in verse or singing, but that's equivalent to spoken-language expressions like "say poetically" or "speak in verse," not the actual rhythm of the verse.

As this is a visual system, the equivalent to the verse literature of Mesoamericans' spoken languages is a painting executed to high artistic standards. (But because the very point of scorning the syllabary and using this unwieldy system is because of its universality and beauty, and since semasiographic works are almost all commissioned by rulers and executed by teams of professional artists, it's a given that almost all codices are exceptionally beautiful.)

Song lyrics for entertainers and such are probably written in merchants' script.

* * *

Also, would there be an interest in me sketching out the "grammatical" elements of the semasiographic system? I imagine that, even though it doesn't encode language directly, what kind of contextual information (the relative position in time of different scenes in the picture, etc.) is explicitly marked by the picture would still be heavily affected by the spoken language. For example, a Mixtec-based semasiography will probably only obligatorily mark past, present, and future because that's what Mixtec verbs do. But a Mayan-based semasiography is more likely to distinguish between scenes that took place in the recent past and ones that took place in the distant past, because that's what Mayan verbs do.

By reading up on the grammatical systems of Nahuatl, Mixtec, and Yucatec Maya (the three most important languages in Mesoamerica, excluding Tarascan) and the conventions of OTL Mesoamerican pictographs, I could probably sketch a semi-plausible series of "grammatical conventions" for the semasiography.

Pros:

- Helps in worldbuilding, and I really like the idea of a not-really-writing system that took things the other way, encoding meaning instead of sounds.

Cons:

- Maybe I'll have a coherent system to draw stuff for future entries, even if I really am not much of an artist.

- Takes time (a few days?), further delaying the chronological progression of the TL (and the arrival of the Europeans, which a lot of people seem to be anticipating)

Thoughts? I'll set up a poll.

I would rather him talk about the regions of this new world instead of grammerI would rather read about grammar and this system being developed than "EOROPEANS!!!" to be honest.

There's no easy answer to your poll. It depends on how you envision it: on one end a full-fledged constructed language (unlikely, bordering on ASB before widespread literacy in already written languages), or an art form with set conventions.

If you want suggestions for more options, there are many, many possibilities. I'd say what you have outlined sounds a bit like Polynesian navigation charts, but applied to storytelling.

Your description also makes me a bit confused: I thought you were making an analogy with the Akkadian/Sumerian situation? It seems to me like this is a whole new thing apart from the syllarbry and the script it's derived from? I mean I don't see what this thing you're describing has to do with the merchants' script (the syllabry)? I thought the script that the merchants' script was derived from was basically kanji+hiragana, or more precisely the way Akkadians used the Sumerian script in the outlying regions that adopted it, and what you're describing now is the thing THAT it's derived from. Maybe like oracle bones of ancient China or Sumerian commercial tokens, but derived from storytelling rather than temple/commerce? Can you clear this up?

EDIT: I seem to recall there's precedent for things like that in cultures north of what your TL has covered so far, but not with grammar, as I said more like navigational charts with a narrative element. I can imagine this being more developed ITTL but at that point IOTL they were already at the Sumerian stage and I though it developing into a syllabry was the advanced element.

If you want suggestions for more options, there are many, many possibilities. I'd say what you have outlined sounds a bit like Polynesian navigation charts, but applied to storytelling.

Your description also makes me a bit confused: I thought you were making an analogy with the Akkadian/Sumerian situation? It seems to me like this is a whole new thing apart from the syllarbry and the script it's derived from? I mean I don't see what this thing you're describing has to do with the merchants' script (the syllabry)? I thought the script that the merchants' script was derived from was basically kanji+hiragana, or more precisely the way Akkadians used the Sumerian script in the outlying regions that adopted it, and what you're describing now is the thing THAT it's derived from. Maybe like oracle bones of ancient China or Sumerian commercial tokens, but derived from storytelling rather than temple/commerce? Can you clear this up?

EDIT: I seem to recall there's precedent for things like that in cultures north of what your TL has covered so far, but not with grammar, as I said more like navigational charts with a narrative element. I can imagine this being more developed ITTL but at that point IOTL they were already at the Sumerian stage and I though it developing into a syllabry was the advanced element.

Last edited:

Brief summary of OTL Mesoamerican writing systems

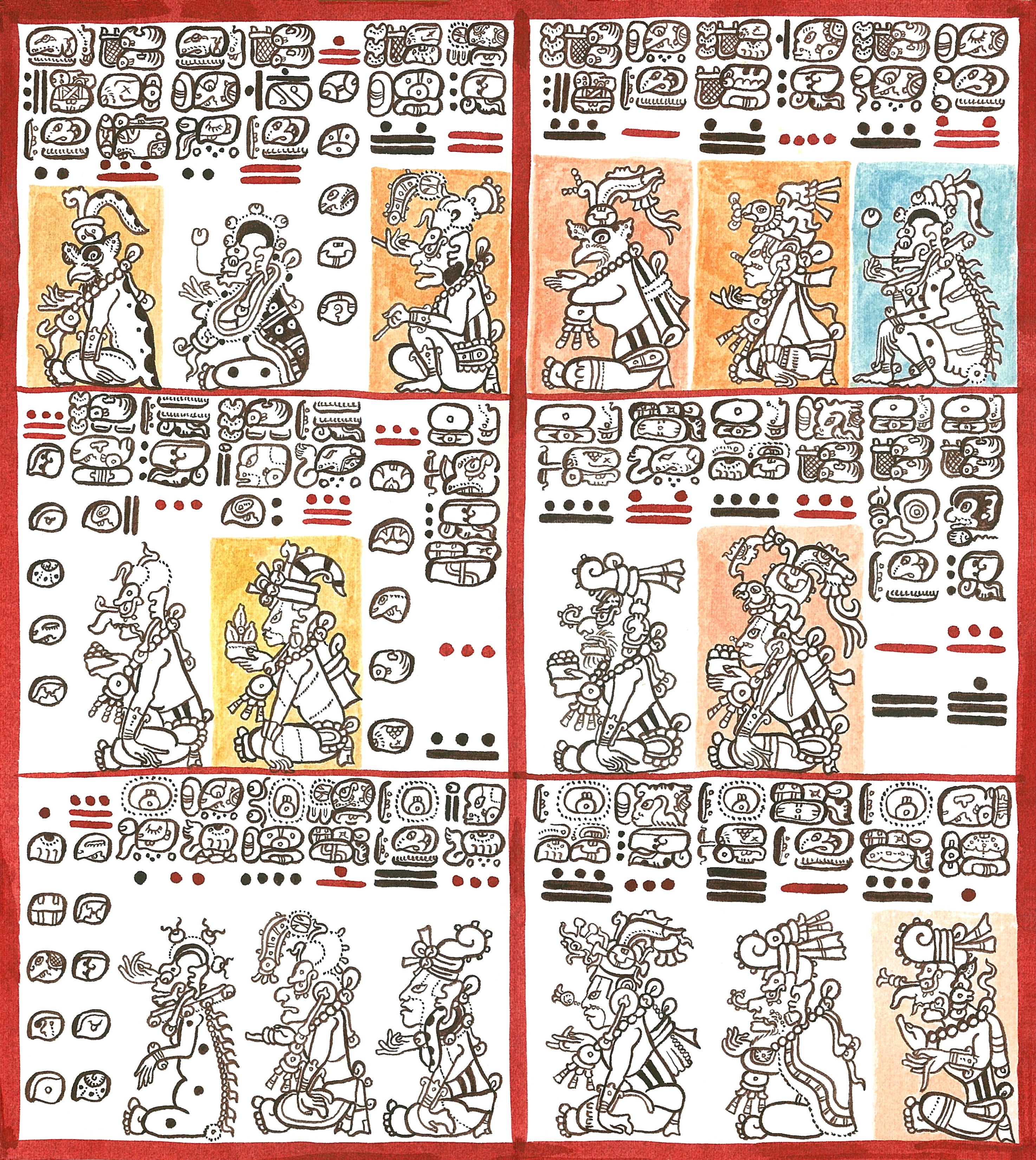

So OTL Mesoamerica had two types of "writing." The first was a logosyllabary, used by the Maya and by Classic-era Zapotecs. One characteristic of this more familiar type of system is that "writing" and "pictures" are clearly distinguishable. Here's an example from the Maya Dresden Codex:It seems to me like this is a whole new thing apart from the sillarbry and the script it's derived from?

Even if you knew nothing about Maya art, you can instantly tell the difference between the written material (the squarish face-looking things) and the painted material (the seated figures).

The second, which technically isn't "writing" because it doesn't encode spoken language, is a semasiographic system used by Aztecs and Mixtecs. This system has a series of artistic conventions by which paintings can be "read." This means that there's no distinction between the written text and the painted material; the meaning is read in the painting. Here's an example from a Mixtec history book, the Codex Zouche-Nuttall:

Other than the names (hovering above the characters), there's no written text to speak of. Does that mean that it's just a painting whose meaning only the painter can understand for sure? No, because it relies on an enormous set of fixed artistic conventions that enable any educated Mixtec to read the codex. Here are the meaning of some of the gestures, for example (from Mixtec Pictorial Manuscripts):

Thanks to these conventions, the same codex could be read and understood by an Aztec scribe even if he didn't speak Mixtec, and even by a hypothetical modern scholar who's memorized the conventions, even if he hasn't bothered to learn Mixtec. And modern historians can, with little ambiguity or risk of misinterpretation, can "translate" the Codex Zouche-Nuttall, which turns out to be about a twelfth-century king of a place called Tilatongo whose lover became married to the ruler of a neighboring kingdom called "Xipe's Bundle." When the king conquered Xipe's Bundle and extirpated its royal family, he found that his former lover had died as well because of his war. Apparently out of compassion and regret, he spared his lover's youngest child. Fourteen years later, the child he spared returned to conquer Tilatongo and sacrificed the king.

It's not "true writing" (writing that encodes spoken language), but once you know the conventions of the art it's still a quite effective means of communication, especially across language boundaries.

Postclassic Mesoamerica had a tendency to prefer systems like these over "true writing."

* * *

What TTL does is take both trends further along and create a state of digraphia, two writing systems used at once:

- The Maya-style logosyllabary fully discards its logographic past and becomes the merchants' script, a full syllabary used for low-prestige purposes.

- The Mixtec-style pictographic system further expands on its system of conventions and further cuts down on ambiguity by inventing ways to mark grammatical elements like tense, and becomes the Mesoamerican semasiography, a visual language of sorts used for high-prestige and artistic purposes.

Threadmarks

View all 86 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Entry 58: The Death of Lord Mahpilhuēyac Entry 59: The Fall of Lyobaa, August 1410 Entry 60: The Fingers' Children Entry 61: The Death of Lord Tlamahpilhuiani, 1411 Entry 62: The Cholōltec War, 1411—1413 Entry 63: Ah Ek Lemba's Oration at Cempoala, 1413 Entry 64: Responding to Defeat, 1413 Entry 64-1: Chīmalpāin's Name

Share: