I doubt it, since they still have a strong supply from the ConfederatesAre the British still ramping up the cotton production in India and or Egypt?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Wrapped in Flames: The Great American War and Beyond

- Thread starter EnglishCanuck

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 157 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

The New World Order 1866 Part 4: The Mexican Empire Chapter 126: The Balance of Power in North America Chapter 127: What If? Chapter 128: 1866 A Year in Review Chapter 129: Grasping at Thrones Chapter 130: Plots in Motion Chapter 131: Trans-Atlantic Troubles Chapter 132: A Want of PreparationI understand that, but imo, cooperation is going to be required in order to see the war come to a successful conclusion. I'm sure Confederates are aiding in the blockade, however minimal their help may be. And I'm sure British supplies are pouring into Confederate ports. For all intents and purposes, their allies in this war whether it's on paper or not.

In the Chesapeake the Confederates aid the blockade with some ships, but primarily by letting the British use Norfolk as a base, which really helps logistically. The British are also selling most of what they sold to the Union to the Confederates here.

However, as has been said, the two are effectively fighting a separate war. The British end goal is not Confederate independence, if it incidentally helps their goals that's great. However, they are not going to be signing a Treaty of Alliance with the CSA anytime soon. Whether they will extend formal recognition to the CSA remains to be seen.

Are the British still ramping up the cotton production in India and or Egypt?

Not quite. The 'Cotton Hunger' of 1863 isn't going to bite, and TTL's cotton embargo only lasted for about 9 months. On the flip side Confederate commerce is doing quite well.

In the Chesapeake the Confederates aid the blockade with some ships, but primarily by letting the British use Norfolk as a base, which really helps logistically. The British are also selling most of what they sold to the Union to the Confederates here.

However, as has been said, the two are effectively fighting a separate war. The British end goal is not Confederate independence, if it incidentally helps their goals that's great. However, they are not going to be signing a Treaty of Alliance with the CSA anytime soon. Whether they will extend formal recognition to the CSA remains to be seen.

l

Not quite. The 'Cotton Hunger' of 1863 isn't going to bite, and TTL's cotton embargo only lasted for about 9 months. On the flip side Confederate commerce is doing quite well.

I’m not actually sure what the point of the British war is. There aren’t all that many strategic goals they have in mind, beyond of course winning. It does seem somewhat unrealistic that they’d be doing so well in the west. The preponderance of land forces seems to favor the Union.

Favor the Union out west? How so? They are using almost all their energy out east, they have next to nothing out west to seriously contest the Brits. In no way, shape, or form does the war out west favor the Union.I’m not actually sure what the point of the British war is. There aren’t all that many strategic goals they have in mind, beyond of course winning. It does seem somewhat unrealistic that they’d be doing so well in the west. The preponderance of land forces seems to favor the Union.

And as a note, Canada will still exist as a nation when this is all done, based on the name of one of the books that one of the first postings in the thread includes.

I make no bones about the survival of Canada. Though how different it is from OTL's Canada is an open question.

I’m not actually sure what the point of the British war is. There aren’t all that many strategic goals they have in mind, beyond of course winning.

The British have stumbled into this war. Lyons ITL said it would be "The greatest and chiefest calamity of our time" which would be a sentiment I agree with (and espouse), and even a few writers OTL said that same. The war is wholly unnecessary, but both sides were not willing to budge on certain key issues.

Back in Chapter 5 the British included their four point ultimatum:

1) The immediate release of the Confederate commissioners

2) The dismissal of both Captain Wilkes and Captain McInstry from naval service

3) The issuing of a formal and public apology on the part of the United States government for the actions undertaken by members of its Navy

4) The United States would pay for the damages to HMS Terror and would provide financial restitution for the damages done aboard RMS Trent. The amount to be paid would be determined solely by Her Majesties Government

OTL (like TTL) they got the release of the commissioners, but Seward refused the apology and Britain was fine with that. TTL, that response would be completely insufficient and so it was. The British were both OTL and TTL operating under the belief that the Union was losing their civil war and would instead try and save face by turning around and annexing Canada. This is why they were so prepared to issue a harsh ultimatum in OTL which was toned down by Prince Albert before he died. Here its not only a worse diplomatic situation, but Albert himself isn't here to tone it down, and the Union isn't really inclined to accept parts 2-3 of that demand. It would be humiliating.

Now you see that the War Cabinet is unwilling to seek terms themselves, and they want to force the Union to the negotiating table. Palmerston is seeking a harsh peace like he got in China in 1860 and unlike what he didn't get in 1856. With lives lost and damage to British prestige and trade at stake, there isn't anyone in his cabinet to tell him no.

Lincoln on the other hand wants some material gain so he can open negotiations on favorable terms. Hence why the gains he's made now (occupying Canada West) aren't what he's looking for.

It does seem somewhat unrealistic that they’d be doing so well in the west. The preponderance of land forces seems to favor the Union.

Ah you'll have to be more specific which 'west' you mean

I make no bones about the survival of Canada. Though how different it is from OTL's Canada is an open question.

The British have stumbled into this war. Lyons ITL said it would be "The greatest and chiefest calamity of our time" which would be a sentiment I agree with (and espouse), and even a few writers OTL said that same. The war is wholly unnecessary, but both sides were not willing to budge on certain key issues.

Back in Chapter 5 the British included their four point ultimatum:

OTL (like TTL) they got the release of the commissioners, but Seward refused the apology and Britain was fine with that. TTL, that response would be completely insufficient and so it was. The British were both OTL and TTL operating under the belief that the Union was losing their civil war and would instead try and save face by turning around and annexing Canada. This is why they were so prepared to issue a harsh ultimatum in OTL which was toned down by Prince Albert before he died. Here its not only a worse diplomatic situation, but Albert himself isn't here to tone it down, and the Union isn't really inclined to accept parts 2-3 of that demand. It would be humiliating.

Now you see that the War Cabinet is unwilling to seek terms themselves, and they want to force the Union to the negotiating table. Palmerston is seeking a harsh peace like he got in China in 1860 and unlike what he didn't get in 1856. With lives lost and damage to British prestige and trade at stake, there isn't anyone in his cabinet to tell him no.

Lincoln on the other hand wants some material gain so he can open negotiations on favorable terms. Hence why the gains he's made now (occupying Canada West) aren't what he's looking for.

Ah you'll have to be more specific which 'west' you meanIs that Canada West or the Pacific slope? I can answer either one, but knowing which helps

Pacific slope I suppose, although I wrote the comment before I realized exactly how many people lived in Canada at this point. Still, it seems hardly likely that they’d move a battalion from a restive area to a place which really was on the periphery of the empire.

Pacific slope I suppose, although I wrote the comment before I realized exactly how many people lived in Canada at this point. Still, it seems hardly likely that they’d move a battalion from a restive area to a place which really was on the periphery of the empire.

So far the war on the Pacific slope has been limited to the British capture of the territorial capital of Olympia and the blockade of San Francisco.

The reason for the British success at Olympia is that, even before the war, the Puget Sound was not prepared to repel steamships. In terms of defences and men it was an afterthought. When the civil war broke out the regulars were transported east to fight, and the militia were either under-strength or non-existant. Most of what was deployed in South West and the Pacific OTL came from California. Here the California Volunteers are all needed in California to guard the coast and garrison San Francisco against any British threat.

Marching north would be too slow, 748 miles from San Francisco to Olympia, and the British rule the seas. They outnumber the Americans on the sea, so men and material must go overland if it gets sent at all. The British moving the 99th Regiment from China gives them an extra 800 men added to the roughly 300 Royal Engineers and Marines already on station, putting 1,000 men ready for action in conjunction with the fleet. With the American Pacific Squadron blockaded the British have freedom on the coasts, and so can land men at will along the coast, except at San Francisco where the Americans have to defend it all costs or lose their influence in the Pacific Ocean completely.

While in pure numbers the Americans outnumber the whole British presence (7 regiments of Volunteer Infantry and 6 companies of Regular troops plus 2 regiments of cavalry and numerous artillery and garrison artillery companies - vs 3 companies of British militia and an Engineer company roughly 2-4 companies of Royal Marines and 1 Infantry regiment) the need to garrison San Francisco (4 regiments) and points south at Fort Yuma, the overland routes, and monitor Indian bands leaves precious little to maneuver against a British incursion. The other problem is the paucity of resources, with most small arms and powder shipped east for the war.

While the British would need to mount a huge effort to threaten someplace like San Francisco, they can at present easily threaten smaller holdings like Olympia. However, for all parties at present this is the periphery of the war.

A Canada that only includes Ontario and land to the east of it is still a very viable nation, although whiter and more Francophone. If that is how the war ends up, it would be interesting to see how Canada develops. Without the western part of Canadian identity it may seem more "European" as it will be far more concentrated and centralized.I make no bones about the survival of Canada. Though how different it is from OTL's Canada is an open question.

A Canada that only includes Ontario and land to the east of it is still a very viable nation, although whiter and more Francophone. If that is how the war ends up, it would be interesting to see how Canada develops. Without the western part of Canadian identity it may seem more "European" as it will be far more concentrated and centralized.

It would still be a viable nation, but certainly a poorer one without Pacific access. I daresay that on both sides of the border there would be a much larger impetus for increased railroad construction no matter how this turns out.

This Canada* (say just Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and PEI) would be far more European looking, seeking better ties with the Mother Country up till the turn of the century as a check on American expansion. Absent the draw to settle the West you'd have more investment in trade, industry, and the Maritimes most likely. Definitely not the most amicable towards its southern neighbor either.

union in 1862 would like look they are losing the civil war but they did not have the right military leaders or resources to win in 1862 neither. the union forces in the east are inept at attacking but a more then able even outnumbered of holding their own in a defensive campaign.

The Union in 1862 certainly didn't look like they were winning the war to foreign observers. With the failure of the Peninsula Campaign, the defeats at Second Bull Run and followed by Lee's invasion of Maryland and then another Federal army being turned back at Fredericksburg? Things seemed grim indeed which was why many foreign observers predicted a Confederate victory until the summer of 1863. After that though, it was a long decline for the Confederate fortunes.

Though as of 1862 TTL, things certainly look worse for the Union.

I'm pleased to say that we shall have two chapters up this weekend and then two chapters the following week. Then I will have to take till mid January to get all the fine technical details down for the first part of the upcoming campaigns of 1863 which will cover from April - June of that year, followed by the campaigns in Canada, the campaigns out West, and then the various odds and sods till I get to July - August of 1863.

But January and February should be reasonably busy for this TL, while it may take until April for me to get the details out West right. However, I am hoping to get 1863 wrapped up by the summer of 2019 and get into 1864 by fall and winter of next year. Maybe I'll even surprise myself and move more swiftly than that?

But January and February should be reasonably busy for this TL, while it may take until April for me to get the details out West right. However, I am hoping to get 1863 wrapped up by the summer of 2019 and get into 1864 by fall and winter of next year. Maybe I'll even surprise myself and move more swiftly than that?

Chapter 48: A War of Conscience Pt. 2

Chapter 48: A War of Conscience Pt. 2

“Our present form of provincial government is cumbrous and so expensive as to be ill suited to the circumstances of the country; and the necessary reference it demands to a distant government, imperfectly acquainted with Canadian affairs, and somewhat indifferent to our interests, is anomalous and irksome. Yet, in the event of a rupture between two of the most powerful nations of the world, Canada would become the battlefield and the sufferer, however little her interests might be involved in the cause of quarrel or the issue of the contest.” - Montreal Annexation Manifesto, published in The Montreal Gazette, October 11, 1849

“The depletion of the Canadian militia from attrition, disease and desertion had been under way since the opening of hostilities in February 1862. While the urban militia battalions displayed a hardier constitution in the field, as evidenced by the York Brigade, the rural battalions saw a higher rate of attrition.

This may be attributed to a number of reasons. The first is that lacking the similar early espirit de corps of the urban battalions, having been merged from numerous disparate companies of otherwise independent militia associations, many broke or suffered disproportionately in their first taste of battle. Only the fire of battle and the rigours of campaign itself would mold them into efficient fighting forces. Even in camp life these units suffered. While the urban battalions had by their very nature been inoculated to various diseases common in urban areas, the rural men were not used to the uncomfortable conditions cramped together in the camps. Nor did many of them pay heed early on to the sanitary guides of their British instructors, much to their detriment. These units were decimated by sickness and disease, and over the winter of 1863 this effect accelerated once battle casualties were accounted for.

The loss of Canada West beyond the Trent River made reinforcing and replenishing the existing militia battalions from that portion of the province difficult. The populations of the rural regions along the St. Lawrence and the farming settlements of the Ottawa Valley did not have the manpower to completely replenish the losses suffered over the previous campaigning season, and in many areas men who had not volunteered were needed at home, never mind that the existing battalions were tied down guarding against sudden American raids and protecting the important lines of communication along the railroads and the Rideau Canal, the only now reliable route for supplies to proceed to Kingston and from there to the front.

In Montreal, Macdonald and the Provincial Government struggled with a way to cope with these losses. Demoralized by the occupation of much of Canada West, many MP’s from that region suggested that it should fall on Canada East to boost the number of Volunteers who would serve in the British army on the shores of Lake Ontario.

Naturally the Canada East MP’s balked at such a proposition. Did they not already have enough men serving in the Army of Canada? Was it not their men who manned the defenses of Quebec and Montreal, and kept the Americans at bay east of Cornwall?

Though critics like Brown and Mowat would sharply protest that the loss of the most populous portions of the Province meant that by default much of the cost of the war would be placed on the Eastern province, Macdonald, Cartier and Monck were all more realistic in their assessment of the ability of Canada East to reinforce the armies in the field. As substantial numbers of MP’s from Canada East were necessary to sustain the coalition, Macdonald could not be insensitive to their needs.

The needs of the war though, were pressing. With many units reduced from battle and disease, there was no choice but to issue another call for Volunteers. The call went out in January for 25,000 men to join the ranks, with the proviso that if these ranks were not filled by March 15th, the ballot would select men not serving from amongst the sedentary militia of Canada East and Canada West…” – Blood and Daring: The War of 1862 and how Canada forged a Nation, Raymond Green, University of Toronto Press, 2002

“…the economic costs in 1863, for such a young nation, were staggering. Millions in tax revenues had been lost, and a provincial legislature which was accruing significant debts could little afford the costs of maintaining a not inconsiderable field force by itself.

Though the costs were largely folded into war spending by the Imperial Government, London did expect that the provinces would adjust to the war with financial sacrifices of their own. The Maritimes and Quebec in particular were drawn heavily upon. The Maritimes did receive some relief as in 1862 – 1863 the number of immigrants ballooned by a factor of four, some 40,000 arriving directly in Halifax, St. Johns, and St. Andrews. Many were drawn by work, especially the work on the roads and the expensive proposition of expanding the railroads north to Tobique and beyond. However, an influx of workers greatly deflated wages, and there were grumblings among the populace.

Similar economic patterns were noted in Canada East, where 60,000 people landed between 1862 and 1863, with over 200,000 coming through Quebec and Montreal between 1864 and 1871. These earlier years, were more chaotic however, as work was not scarce, but wages again fell steadily. Though some of these immigrants did indeed volunteer to take the Queen’s shilling, it was apparent that neither purely patriotic rallying nor the enticement of bounties could bring all manner of people to the ranks…

…The government’s call for men was examined, and found to have fallen short by seven thousand men. Only a further 18,000 had joined the ranks, and many of these attached to existing companies. With pressure from the British forces, anxious for a summer campaign, the Macdonald government was forced into action. On the 20th of March, an announcement was circulated that if the remaining men were not found, the ballot would need to be introduced.

There was call that the announcement should wait until the 23rd, when the God fearing men and women of the province would all be at church and the news softened by the power of the Church, but military concerns overrode those of the Governor General and the Provincial Parliament…” The Road to Confederation, 1863 – 1869 the Formative Years, Queens University Press, Donald Simmonds

“The first rumblings of discontent were known only a day after the announcement, when on the 21st, crowds of men, mostly Irish and French laborers from the docks of Montreal, gathered in the St. Lawrence Market. Many had been drinking the previous evening, and the news of the announcement had spread rapidly among them. The slow winter months, coupled with increasing competition for work meant that there were “many idle hands in the city, a populace well place to cause great mischief” according to Tache. Though the day was largely only interrupted by inflammatory speeches from members of the Institut de Montreal. The night ended calmly, with few disturbances reported. However, the morning would be electrified by events 15 miles away…” – Blood and Daring: The War of 1862 and how Canada forged a Nation, Raymond Green, University of Toronto Press, 2002

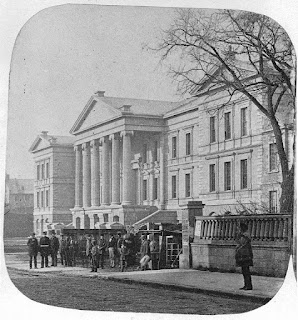

Fort Chambly and environs, 1840

The fort itself, like most of the fortifications pressed into service in the winter of 1861-62, had seen better days. The original fortifications dated back to the Ancien Regime, built to protect the river from British encroachment. They were occupied by the British, facing the ill-fated American invasion in 1775 and the War of 1812, then again guarding the river from rebels in 1837-38 and being used as a prison. Abandoned in the 1850s, they had again been hastily reoccupied.

In these fortifications the men of the 36th had drilled, but battled nothing more than boredom for over a year. They felt they were doing their duty, but when a rider came proclaiming that the ballot was instituted, many were outraged. Though there were reports of grumbling among the men, Col. Archambalt displayed no worries. He retired that night, along with his staff, and there is no sign he saw the events of the morning coming.

At dawn on the 22nd, he was roused roughly from his bed by his junior captains, and along with his staff and members of the British Military Transport Service, placed in the cells within the fort. In the night men from Montreal had appeared and spread the rumour that the ‘British’ (a vague term if there ever was one in this situation) were arresting dissidents. The rumour was obviously false, but it serves to illustrate the state of excitement which sprang up overnight. The news of the mutiny again would travel by dispatch rider, reading Montreal late the afternoon of the 22nd…” – Canada and the Draft: A History of Disservice, Martin Laberge, McGill University, 1989

“News of the Chambly mutiny electrified crowds in Montreal. The yard and factory workers were still largely without work, and were in a mutinous mood. Most gathered at the St. Lawrence Market, while some few were gathered along the roadways near Bonaventure Station, clogging the tracks.

During the night, the Montreal garrison had been put on alert. Chief of the Montreal Police and Major in the militia Guillaume Lamothe had scrambled men from his commands towards important points in the city, a detachment watching at the market and another at the station. Colonel Dyde commanding the garrison, had gathered six companies of the Montreal Light Infantry, and five of the 55th Volunteers at the Champ de Mars, alongside some mounted men in anticipation of trouble.

Trouble was had when it was announced that men had assembled on the Champ de Mars, and the crowds came to believe they were to be attacked. Angrily they marched on the courthouse, intending to burn civil records. Captain Eugenie Flynn of the police read the riot act, ordering the crowd to disperse, but after a short skirmish he and his men were bulled aside and the mob moved on. Having swollen to nearly 2,000 individuals, the gathered at the court house and began throwing stones and attempting to force entry.

It was at that moment, a semi-leading figure emerged, Denis Papineau, a member of the Institut, he, along with others, rallied the crowd to resist. However, at that moment, the police and militia, led by Dyde, arrived. They again read the riot act, and again the mob refused to disperse. This led to another tense standoff as Dyde attempted to calm the crowd, he announced a delegation would be coming from the Bishop’s Palace.

The Montreal Court House

That night martial law was declared in the city. On the morning of the 23rd armed militia patrolled the streets, and British cavalry from the 13th Hussars were arriving. The 23rd was mostly calm, and many attended church. Bishop Bourget delivered a stern sermon, reminding the parishioners of their duty to the Crown and the Church, and that civil disobedience was not to be countenanced…

…during the night however, many had fled ahead of the announced draft proposals. Throughout the 23rd and 24th some 500 men joined the mutineers at Chambly. There were soon 1,000 armed men encamped at the fort. Though less than half were mutineers, the remainder were old die hard patriotes who sensed a chance to fight injustice, among them Denis Papineau himself and others like Arthur Buies and George Green.

They expected a showdown, and when on the morning of the 25th they noted mounted men and troops marching towards the fortifications, they expected the worst. However, after a day of digging in, no shots were exchanged. Both sides merely stared at one another quietly.

On the afternoon of the 26th, a sled could be seen approaching the fort under a flag of truce. Out of the sled walked Col. Tache. Accompanied only by a secretary, he requested to speak with the leaders at the fort. After some discussion, a collection of the mutinous officers and local dignitaries approached. Tache handed them a letter from the Archbishop, and he was invited inside to discuss matters with the mutineers and ‘rebels’ who now held the fort…

The whole meeting was, in a sense, a victory for the Canadians. Dundas, upon learning the news of riots and mutiny, had promptly ordered troops north to suppress it, intending to take the fort by storm. However, Monck and Macdonald, with input from Tache, had convinced him to stand down. Monck, diplomatic by nature, and Macdonald remembering the events of Montgomery’s Tavern and the Windmill, felt it would be better to first treat with the men and avoid bloodshed. While Dundas was scornful of the idea, he allowed the meeting to go ahead.

It was fortuitous. Tache managed to secure the surrender of the men inside under generous terms. The men who had taken up arms not in the militia, were simply allowed to return home, while the militiamen themselves would be paroled to their own homes. Their officers who had taken part in the mutiny however, were arrested awaiting trial…” – Blood and Daring: The War of 1862 and how Canada forged a Nation, Raymond Green, University of Toronto Press, 2002

Buies

Though little has been said about the timing with Lincoln’s ‘moral imperative’ of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Though there are many popular accounts to suggest that the Canadian populace was overall receptive to the Emancipation Proclamation, there has been little comment on the moral effect it might have had. Certainly some have considered the anecdotal evidence, but little has been spoken openly on those suspicions. Perhaps it falls to the unjustly unknown Arthur Buies to speak on them.

Having deserted his allegiance to the 55th Battalion of Volunteers in the aftermath of the riots, Buies fled southwards to American lines after the surrender of the mutineers at Chambly. Though he would join the 4th Battalion of Canadian Volunteers in New York, he never saw action with the unit, it being relegated to garrison and communications duties. He remained in New York until 1870 when he returned, perhaps his trip having been made easier for not bearing the ‘stain’ of fighting against his fellow countrymen. But his Letter of an Errant Canadien (1864) is fascinating in its content, to whit:

“The imposition of the draft upon the peaceful peoples of Eastern Canada was one which any man must find intolerable, bringing to mind all the horrors and injustices of 1837. But when one considers than then our own swords were taken up in the defence of Empire and Tyranny, how could any truly patriotic son of Canada not see that Lincoln’s government meant to end all those hated aspects of English life. Aristocracy, Autocracy, and Slavery. Each evil the Lincoln government railed against, with their war on the Slaver Aristocracy of the South and the Imperial Aristocracy of Britain, how can any man not take up arms for this cause?”

Tragically, this sentiment has often been overlooked. Buies himself was one of the most radical members of the Institut’s second generation. Its gradual decline from 1858 to 1881, due to the turn to ultramonte politics by the Quebec establishment has left much of early Liberal sentiment from the era unresearched. Certainly the makings of the modern Liberal Party, born in the tumultuous early elections and the soul searching done in the 1880s, has sought to forget its more radical roots.

Unfortunate tendencies such as these produce an unwillingness to address pre-Canadian resistance to draft and military policies…” – Canada and the Draft: A History of Disservice, Martin Laberge, McGill University, 1989

“…in the end the draft went ahead. Macdonald’s government would have much to answer for after the war, but both Dundas and Macdonald got what they wanted. 5,000 men would come forward, leaving only 1,000 to be filled out by ballot.

By accepting the ballot it can be argued Macdonald bungled much of the compromise he had made when forging the Great Coalition in 1862. However, with those most decidedly opposed to the ballot amongst the rouges either in the political wilderness or disgrace following the riots and mutiny, the bleu members of his coalition sat comfortably in their seats. The powerful defection of McGee the previous year and the stalwart support of the Church would insulate them against the worst of the crisis and anger which followed. Irish and French opinion would be steered solidly towards the Church, while the war itself raged on, leaving all opposed to the rouges well known support for annexation.

The Coalition though, saw its first early strains…” Nation Maker: The Life of John A. Macdonald, Richard Chartrand, Queens University Publishing, 2005

Last edited:

RodentRevolution

Banned

Well that was a commendably tense chapter and a good look at some oft overlooked fault lines within Canadian society.

Well that was a commendably tense chapter and a good look at some oft overlooked fault lines within Canadian society.

I'm glad it was tense! Though I'd hardly say some of it is unknown, as Canada really hasn't seen a major war without Francophone Canada expressing some level of discontent. I mostly based this on the Lachine Riot from OTL's 1812 war, while the mutiny is actually pretty extreme in light of most of Canadian military history.

s

Chapter 49: War's Evils

Chapter 49: War's Evils

The Champ de Mars, Montreal, April 2nd, 1863

Macdonald watched with some dissatisfaction as the two men were led out by their comrades. A large crowd had gathered, and he felt distinctly at unease. Though he sensed less hostility, and more curiosity. Beside him stood Cartier, Lysons, and Tache. Both the soldiers looked resplendent in their well polished dress uniforms, and the city fathers looked no less so. Mayor Jean-Louis Beaudry in full regalia, Bishop Bourget, John Redpath, George Stephen, and even Dorion were attending.

“I still find this distasteful.” He said, taking another nip from his flask. “I saw enough fools killed in 1838. Well meaning fools, but fools all the same. Shooting them seems like such a spectacle.”

“The men who occupied Windmill Point were hardly serving in Her Majesties forces.” Lysons said. “Those American bandits got what they deserved, and we cannot do anything but treat the mutineers here the same way. It is the law, military law, and we must maintain discipline, especially in these times, hangings would do no good here.”

“I relish this no more than you Monsieur Macdonald.” Tache added. “I treated with them myself, but I never promised them all amnesty. Besides, on the terms agreed the 36th Battalion was disbanded, and such a step must be heralded by those responsible being held accountable. The trial was held by a Volunteer tribunal, and our men, Canadien men, found them guilty. It is only fitting that we carry out the sentence.” He indicated the posts erected at the end of the parade ground.

The two mutinous captains were led, gently, by soldiers of the 5th Battalion to the posts. A priest accompanied them, and the two were tied without incident. Both men accepted blindfolds, but only one the cigarette. They were given a few moments to confer privately with the priest, before he walked behind the line of men assembling. A captain in the 5th stepped beside his men, sword drawn. Colonel Dyde stepped forward to read the charges to the assembled crowd.

As he did Cartier spoke up.

“I can understand their urge to take up arms.” That earned him narrowed eyes from Tache. “I was young and exuberant myself in ’37. We fought for what we believed was right. I don’t know if those men were wrong to fight, but I have discovered that the violence only begot more violence, and those who live by the sword shall surely die by it.”

“Hence why you’ve hitched your horse with me.” Macdonald smiled. Cartier favored him with a grin.

“We’ve accomplished more via the ballot than was possible with the rifles we had. This Coalition we have created is too important for us to be divided by petty issues over the ballot. We’re fighting for our very survival, and that has already cost lives. These men do a disservice to their home by hindering any defence of it.”

“Quite right sir.” Lysons said. “Though I find the ballot an unseemly process myself, men should not take up arms against their Sovereign. This government has been just, and acted well within the law. Whatever their reasoning, we have handled them gently, more gently than they deserve at any rate.”

Dyde finished his own small speech and stepped back. The militiamen stepped forward.

“Ready!” Cried the captain raising his sword. Macdonald took another sip from the flask.

“Aim!” The rifles rose and men took to knee.

“FIRE!” He chopped his sword forward and the rifles cracked as one. The men on the posts jerked as they were perforated with shot, and then fell limp. A few cries of shock went up from the crowd, but it was soon deathly quiet.

“It is done.” Lysons said. Macdonald shook his head, thinking back to the faces of the men imprisoned in Fort Henry all those years ago, the thunder of the cannons at the Tavern, he thought of the faces of the men lined up for battle just 30 miles to the south. It’s a long way from done, he thought quietly to himself.

Whitehall, London, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, April 4th 1863

“I tell you again it is a weapon!” Gladstone exclaimed emphatically. Palmerston hid a sigh. Gladstone was going on again about an issue he had not been keen to drop since October last. Both Somerset and Russel were nodding with him as he trundled on regarding the merits of the Confederate States.

Palmerston himself however, was thoroughly tired of the rousing arguments being trotted out before the Cabinet. As Gladstone paused for breath he loudly rapped his knuckles on the table.

“Now gentlemen, to business.” He said smiling thinly. Gladstone looked as though he would object, but instead grumbled and took his seat. Soon he would manage to force Palmerston’s hand, but Palmerston would hold that off as long as possible.

“What news from the east?” Palmerston asked gravely.

“The Russians continue their subjugation of Poland, though now they have dispatched men to Lithuania as the uprising there becomes more serious. It seems that the French protests on the part of the Poles has come to naught, and Austria shows no interest in aiding them. Though we’ve rained protests down on the Tsar’s head he has been stonily silent or dismissive of our missives.”

“Any sign of a reaction to the Greek crisis?” Palmerston asked.

“Not as of yet. The Russian army seems completely intent on the crushing of the revolution, they’ve paid little mind to events in Greece it seems. The Polish rising could not be more fortunately timed in that regard. Our show of force in the Ionian Islands should serve to deter any adventurism on their part.”

“This is just as well.” Lewis added. “The secret convention between Prussia and Russia is most distressing. Threatening to combine their arms to crush the Poles, its atrocious. That fellow Bismarck has no shame!”

“If he has no shame should we fear he will goad the Gallic Bull to arms?” Palmerston asked. The specter of war had seemed very real when the Poles had risen in revolt three months ago. Russel shook his head.

“The French and the Austrians have condemned it as we have. I doubt either the Tsar or Prussian King feel they would be strong enough to invite the wrath of all Europe over the Polish question. We shall see how the Emperor in Paris plays his cards, but as he is digging himself deeper in Mexico I will be surprised if he pushes for war this year.”

“This year at least.” Palmerston grumbled. “Though speaking of this year, how has our planning developed over the winter?” Somerset was first to speak, regarding a pile of reports in his hands.

“We have the most recent reports from Admiral Milne just in yesterday from one of our steamers. He reports Cochrane’s ‘Particular Service Squadron’ has been most active in vexing the American coasts. It has bombarded Portsmouth again, and visited destruction on numerous smaller American inlets with fortifications. He believes this will keep the Americans guessing as to our naval intentions, as well as mounting further pressure on the American mob to negotiate.”

“Any further debacles we should be aware of?” Palmerston asked. Somerset bit back a retort and steamed on.

“The American squadrons in action have been in harbor for the winter months. Admiral Farragut’s ships have not bestirred themselves since November, and nor has a single one of our patrols been seriously challenged save by their batteries ashore. It is Milne’s opinion they are husbanding their resources for a push later in the year. Though he regrets to report that the winter months have roughly impacted his vessels serving off New York and Massachusetts.”

“Such is the fair weather of North America.” Gladstone snorted. “I assume he will be sending those ships on home for repair?”

“Naturally.” Somerset said. “He however assures us that none of this will interfere with his proposed operations this spring.”

“I for one remain leery of these operations.” Granville said. Lewis nodded as well. “All the frustrations of Sevastopol might be repeated, why are we to believe that this General Lee will deliver upon his lofty promises?”

“Come now, it is not as though I am proposing we divert troops from the Army of Canada or the Army of New Brunswick to help here.” Palmerston protested. “Milne has been supportive of acting in concert with the Confederate army for over a year now, and our own reports from Fremantle suggest that their army is much improved from the spring. Besides, General Lee led a daring raid into Maryland just this November, with the support of the fleet what might he accomplish now?”

“With two fleets we were vexed by the French in the Crimea.” Lewis recalled acidly. “I too am concerned, but so long as we are not removing men from our own goal we ought to be reasonably certain to avoid bad press if all goes wrong.”

“I am hoping that you gentlemen remember that in 1814 our fleet alone helped burn Washington and threatened Baltimore while sealing up their coast from Maine to New Orleans.” Palmerston said. “Now we will be helping one-hundred thousand Confederates with our fleet, we might end the war in a season! In conjunction with the Army in Canada and our gains in Maine and on the Pacific what hope has Lincoln to fight on?”

“We must hope he will finally see reason.” Granville said. “Why he did not seek terms last fall is beyond me.”

“The American mob must be placated.” Palmerston said dismissively. “He must have something to show so he is not thrown out of office. I have heard his enemies made significant gains last year, and this is sure to startle him. Lincoln and Seward are ever at the mercy of their newspapers and voters, it will drag this war on beyond reason.”

There were nods of agreement around the table. None doubted that the war was driven by the whims of the American populace rather than the proper decision making process exercised by a common sense Parliament. Palmerston himself was quite comfortable in thinking that if the people of the Disunited States desired a harder war he would gladly give it to them.

“The Army in Canada is quite ready for service.” Lewis replied. “Dundas has formally organized the army into three corps-”

“Three corps?” Granville asked.

“Yes, two in Canada East under Paulet and Grant, and Williams has been reassigned to Canada West to command the Third Corps. We have a spare division operating with the army in Canada East, and our reserve division in Halifax under Windham if any trouble should arise in Maine or the Canadas. All told, there are forty-eight thousand men under arms in Canada East ready for the spring campaigning season. All Dundas waits on is the thaw.”

Palmerston made no effort to hide his smile. Nearly fifty-thousand British troops poised like a dagger over the heart of the United States. True there was some fear that the whole expedition might end up like Burgoyne at Saratoga, Palmerston felt no difficulty would be forthcoming. The timid Williams had been dispatched elsewhere, and a hard fighter was leading the army now. They had effectively occupied all of Maine, and were poised to strike a blow at the heart of American industry.

“Then once the thaw arrives, I cheerfully anticipate in a month, two months at most, we shall hear Dundas is establishing his headquarters in Albany. Then, we can hope Lincoln and Seward will come to their senses and seek terms.” Palmerston said. “And with that, victory will be in our grasp.”

Threadmarks

View all 157 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

The New World Order 1866 Part 4: The Mexican Empire Chapter 126: The Balance of Power in North America Chapter 127: What If? Chapter 128: 1866 A Year in Review Chapter 129: Grasping at Thrones Chapter 130: Plots in Motion Chapter 131: Trans-Atlantic Troubles Chapter 132: A Want of Preparation

Share: