Woah, my 15 minute shitpost got 10 likes. In all honesty, I've been super stressed to the point of almost getting sick from it, and some other IRL stuff kinda drained me. But the fact that this little map got attention makes me honestly feel way better. I'm gonna have something good for y'all this week. I'm thinking either something having to do with Manicheanism, or something having to do with a Gnostic Protestant Reformation, or maybe something else. But y'all honestly made my day. So thanks to all

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Map Thread XVII

- Thread starter Upvoteanthology

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Isaac Beach

Banned

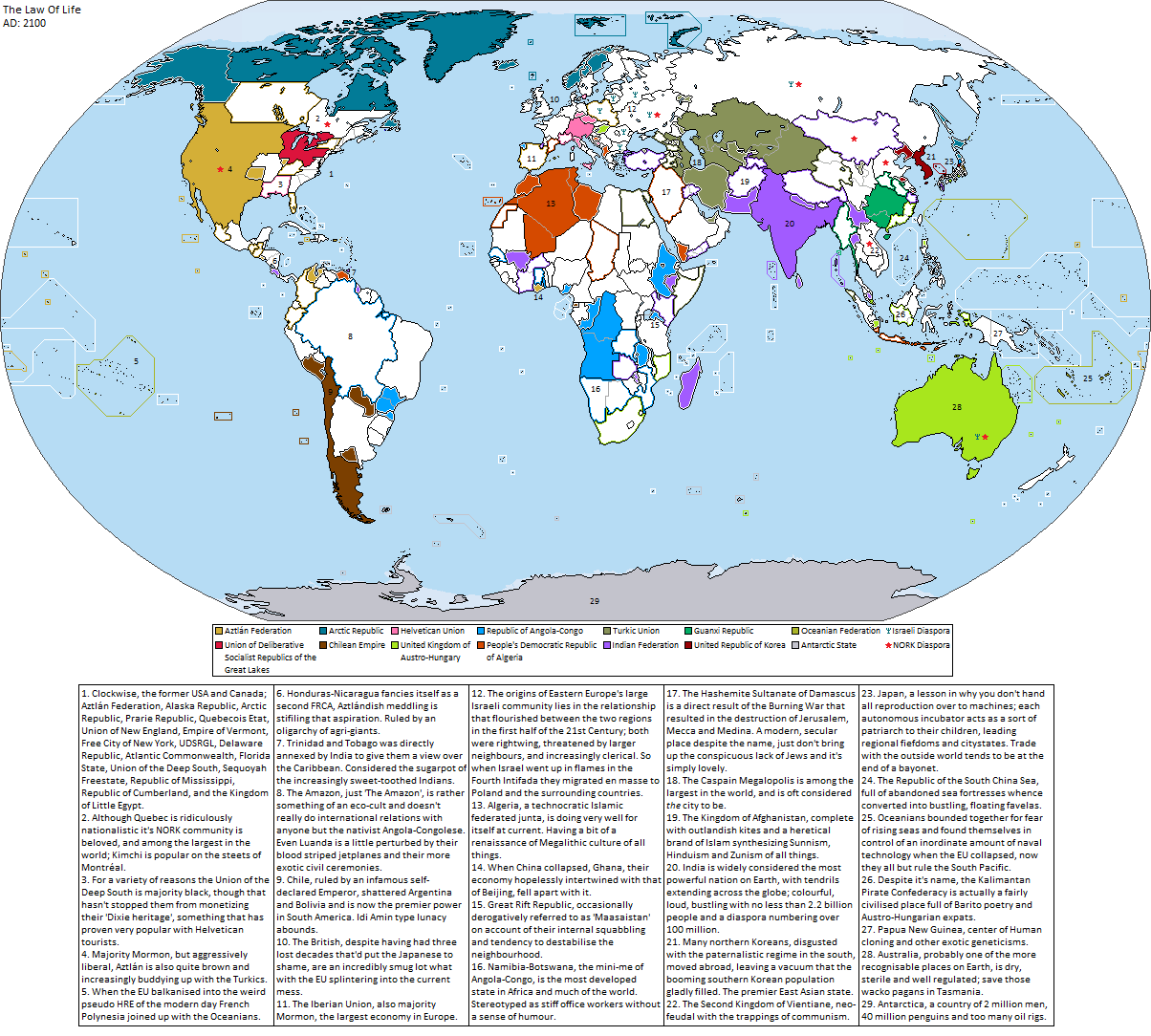

So I recently made a map detailing my realistic interpretation of the state of the world in 2100, something I'm still writing the blurb for. As an aside to that and other maps, I decided to make a somewhat ridiculous map about how the world could turn out in the same period, but with wackier results.

So naturally pretty much everything balkanised, and for it you've got such wild things as a Mormon majority Aztlan, a communist Great Lakes based on Council Communism, a wannabe Napoleon popping up in Chile, a technocratic Algeria, a Helvetican Union that looks as though it came out of a 'period manga' smack bang in the middle of post-EU neo-feudal Europe, naturally the United Kingdom of Austro-Hungary, a nativist Angola-Congo, mega Turkic Union, Indian hyperpower, a neo-feudal autonomously reproductive Japan, a silly Oceanian mega-state I made to fill space, and independent republics at either pole that'd put the Water Tribes to shame.

Oh and NORK and Israeli refugees after both of their respective states were essentially atomised, the latter of which arose from a discussion in the Future History thread about restoring Eastern Europe's Jewish communities that I could only imagine happening if Western Europe simultaneously became incredibly anti-Semitic and Israel itself exploded.

Admittedly it's not actually as silly or ASB as it could be, all things considered, and that's probably because it's not my area of expertise. I'm not that creative at coming up with 'bizarre' circumstances, but I like what I did here. Hope you do to!

Oh, and the name of the map comes from a misappropriated quote from John F. Kennedy, which I only put in because I've been watching a lot of Mad Men.

So naturally pretty much everything balkanised, and for it you've got such wild things as a Mormon majority Aztlan, a communist Great Lakes based on Council Communism, a wannabe Napoleon popping up in Chile, a technocratic Algeria, a Helvetican Union that looks as though it came out of a 'period manga' smack bang in the middle of post-EU neo-feudal Europe, naturally the United Kingdom of Austro-Hungary, a nativist Angola-Congo, mega Turkic Union, Indian hyperpower, a neo-feudal autonomously reproductive Japan, a silly Oceanian mega-state I made to fill space, and independent republics at either pole that'd put the Water Tribes to shame.

Oh and NORK and Israeli refugees after both of their respective states were essentially atomised, the latter of which arose from a discussion in the Future History thread about restoring Eastern Europe's Jewish communities that I could only imagine happening if Western Europe simultaneously became incredibly anti-Semitic and Israel itself exploded.

Admittedly it's not actually as silly or ASB as it could be, all things considered, and that's probably because it's not my area of expertise. I'm not that creative at coming up with 'bizarre' circumstances, but I like what I did here. Hope you do to!

Oh, and the name of the map comes from a misappropriated quote from John F. Kennedy, which I only put in because I've been watching a lot of Mad Men.

So I recently made a map detailing my realistic interpretation of the state of the world in 2100, something I'm still writing the blurb for. As an aside to that and other maps, I decided to make a somewhat ridiculous map about how the world could turn out in the same period, but with wackier results.

So naturally pretty much everything balkanised, and for it you've got such wild things as a Mormon majority Aztlan, a communist Great Lakes based on Council Communism, a wannabe Napoleon popping up in Chile, a technocratic Algeria, a Helvetican Union that looks as though it came out of a 'period manga' smack bang in the middle of post-EU neo-feudal Europe, naturally the United Kingdom of Austro-Hungary, a nativist Angola-Congo, mega Turkic Union, Indian hyperpower, a neo-feudal autonomously reproductive Japan, a silly Oceanian mega-state I made to fill space, and independent republics at either pole that'd put the Water Tribes to shame.

Oh and NORK and Israeli refugees after both of their respective states were essentially atomised, the latter of which arose from a discussion in the Future History thread about restoring Eastern Europe's Jewish communities that I could only imagine happening if Western Europe simultaneously became incredibly anti-Semitic and Israel itself exploded.

Admittedly it's not actually as silly or ASB as it could be, all things considered, and that's probably because it's not my area of expertise. I'm not that creative at coming up with 'bizarre' circumstances, but I like what I did here. Hope you do to!

Oh, and the name of the map comes from a misappropriated quote from John F. Kennedy, which I only put in because I've been watching a lot of Mad Men.

View attachment 355528

Nice map, dude. Gotta admit that the whole uber-Aztlan thing was especially interesting for me, as you don't see that often.)

(TBH, though, I do have to be honest: your other scenario on DevArt is itself a bit iffy plausibility wise and is kinda wacky itself in some respects; I mean, fascist France? A white ethnostate in the south of Brazil? In 2100?)

Isaac Beach

Banned

Nice map, dude. Gotta admit that the whole uber-Aztlan thing was especially interesting for me, as you don't see that often.)

(TBH, though, I do have to be honest: your other scenario on DevArt is itself a bit iffy plausibility wise and is kinda wacky itself in some respects; I mean, fascist France? A white ethnostate in the south of Brazil? In 2100?)

Thanks! I thought it was neat; I didn't want to go down one route where the US get's screwed and everywhere else does well, but not the complete opposite either, so making a new nation out of thin air seemed more interesting and a decent middle-ground.

Well it wouldn't necessarily be fascism as we would understand it; it's a flexible ideology, I would think, and over a century from WWII I would suspect that it would be well enough forgotten that a similar political climate may arise that allows a totalitarian regime of some sort to come to power. I don't predict a smooth ride for Europe in the coming century, and while it's not a given that France could slide into fascism it's hardly implausible. Though I do agree it's unlikely, and something of a trope in current future history scenarios.

Again, that's based on the fact that Brazil at the moment is very ethnocentric in it's media and politics. If you watch Brazilian media you'll notice that almost everyone in it is white, despite the fact that just over half of Brazil isn't. It's not problematic currently as the country has rather larger problems to deal with (drugs, corruption, the economy, etc.) but I could see a negative reaction were the state to move towards a more multicultural policy, especially in Rio Grande do Sul which is one of the whitest states in Brazil. Racial progress doesn't move linearly, and I suspect it will take a long time for Brazil to reach the same state of affairs as much of the developed world (which still isn't all that good at the moment), and as such I don't see racist insurgencies as altogether unlikely, especially given that as of the map's currency the world is going through something of an upheaval or transition.

Thanks! I thought it was neat; I didn't want to go down one route where the US get's screwed and everywhere else does well, but not the complete opposite either, so making a new nation out of thin air seemed more interesting and a decent middle-ground.

Well it wouldn't necessarily be fascism as we would understand it; it's a flexible ideology, I would think, and over a century from WWII I would suspect that it would be well enough forgotten that a similar political climate may arise that allows a totalitarian regime of some sort to come to power. I don't predict a smooth ride for Europe in the coming century, and while it's not a given that France could slide into fascism it's hardly implausible. Though I do agree it's unlikely, and something of a trope in current future history scenarios.

Again, that's based on the fact that Brazil at the moment is very ethnocentric in it's media and politics. If you watch Brazilian media you'll notice that almost everyone in it is white, despite the fact that just over half of Brazil isn't. It's not problematic currently as the country has rather larger problems to deal with (drugs, corruption, the economy, etc.) but I could see a negative reaction were the state to move towards a more multicultural policy, especially in Rio Grande do Sul which is one of the whitest states in Brazil. Racial progress doesn't move linearly, and I suspect it will take a long time for Brazil to reach the same state of affairs as much of the developed world (which still isn't all that good at the moment), and as such I don't see racist insurgencies as altogether unlikely, especially given that as of the map's currency the world is going through something of an upheaval or transition.

Well, okay. Thanks for clarifying things, then.

hows non Nicaragua central america and Caribbean. whats mass entertainment and media like. besides Mormonism, what other changes happen to religion. hows Ecuador,Paraguay,and Uruguay. hows new Zealand?So I recently made a map detailing my realistic interpretation of the state of the world in 2100, something I'm still writing the blurb for. As an aside to that and other maps, I decided to make a somewhat ridiculous map about how the world could turn out in the same period, but with wackier results.

So naturally pretty much everything balkanised, and for it you've got such wild things as a Mormon majority Aztlan, a communist Great Lakes based on Council Communism, a wannabe Napoleon popping up in Chile, a technocratic Algeria, a Helvetican Union that looks as though it came out of a 'period manga' smack bang in the middle of post-EU neo-feudal Europe, naturally the United Kingdom of Austro-Hungary, a nativist Angola-Congo, mega Turkic Union, Indian hyperpower, a neo-feudal autonomously reproductive Japan, a silly Oceanian mega-state I made to fill space, and independent republics at either pole that'd put the Water Tribes to shame.

Oh and NORK and Israeli refugees after both of their respective states were essentially atomised, the latter of which arose from a discussion in the Future History thread about restoring Eastern Europe's Jewish communities that I could only imagine happening if Western Europe simultaneously became incredibly anti-Semitic and Israel itself exploded.

Admittedly it's not actually as silly or ASB as it could be, all things considered, and that's probably because it's not my area of expertise. I'm not that creative at coming up with 'bizarre' circumstances, but I like what I did here. Hope you do to!

Oh, and the name of the map comes from a misappropriated quote from John F. Kennedy, which I only put in because I've been watching a lot of Mad Men.

View attachment 355528

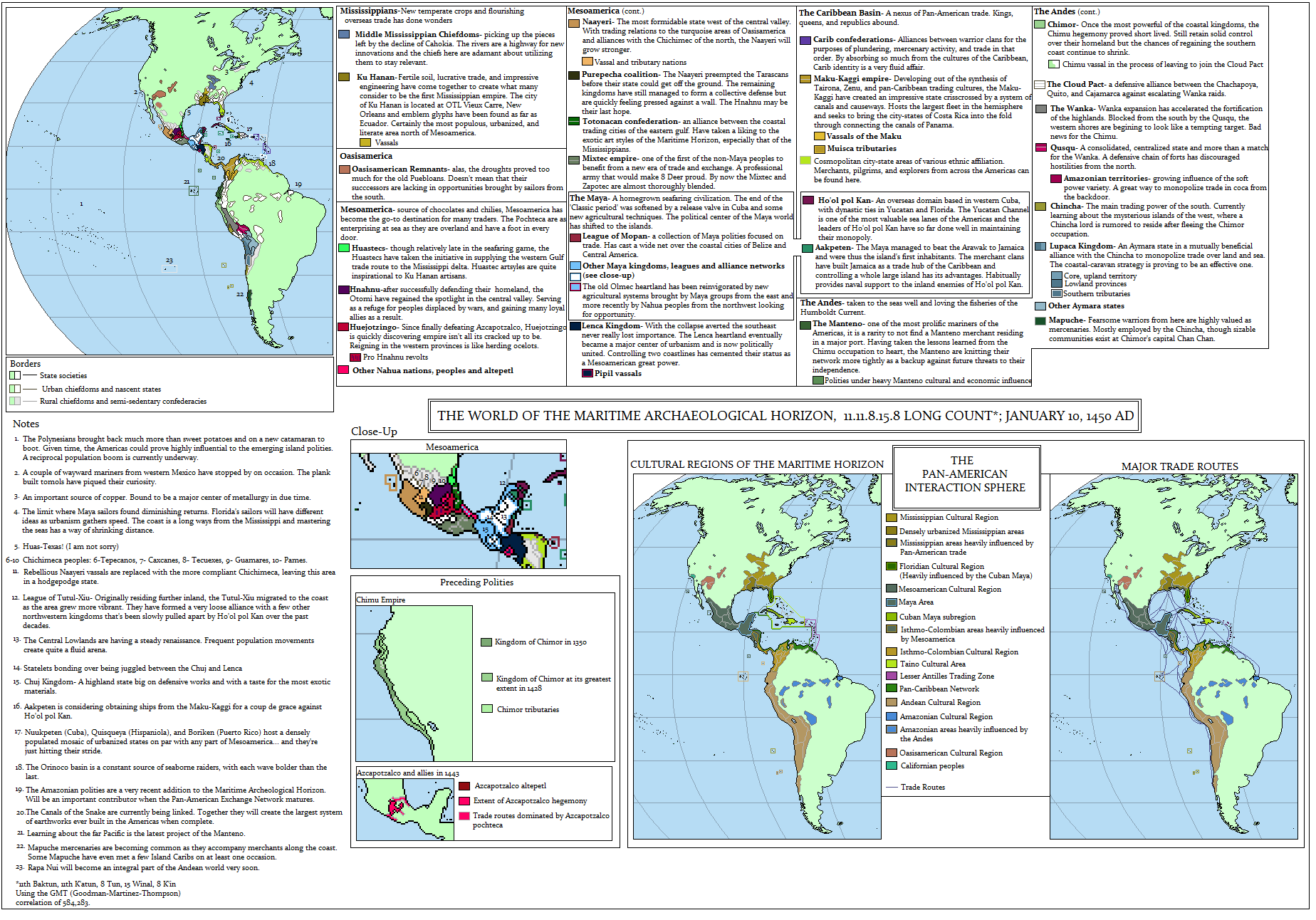

After eons observing the amazing maps by everyone, I've finally completed my first contribution to a Map Thread!

So a while ago in Before 1900 there was a thread titled 'Maya/Mesoamerican Colonization of the Caribbean' (created by @Cuāuhtemōc), wherein a gradual development seafaring technology in the Yucatan peninsula eventually leads to an interconnected trade and exchange network between most of the major cultural regions of the Americas. The POD is essentially the same as 'Bronze Age New World' but with the development of outriggers occurring in the city of Muyil as opposed to the Orinoco. The thread is now too old to reply but the amount of great ideas by everyone in the thread provided an excellent framework for world building.

Inspired by the ideas explored in the thread, I decided to build on this concept and give an impression on the potential ways this world could develop and look like.

@Skallagrim brought together the ideas developed in the thread into a coherent timeline which can be found on page 2. I will post it as a write-up consisting of Skallagrim's master post with additional information that was discussed in the thread along with details on the map itself. Special thanks to the many contributors to the thread @Achaemenid Rome, @Skallagrim, @Cuāuhtemōc, @John7755 يوحنا, @twovultures, and many others.

There were also many divergent and interlocking TL ideas in the thread (contact with West Africa or Trans Pacific trade for example) that may not have been able to be fully fleshed out in a Before 1900 thread alone that I would like to explore at one point. They would make for very interesting worlds on their own.

So a while ago in Before 1900 there was a thread titled 'Maya/Mesoamerican Colonization of the Caribbean' (created by @Cuāuhtemōc), wherein a gradual development seafaring technology in the Yucatan peninsula eventually leads to an interconnected trade and exchange network between most of the major cultural regions of the Americas. The POD is essentially the same as 'Bronze Age New World' but with the development of outriggers occurring in the city of Muyil as opposed to the Orinoco. The thread is now too old to reply but the amount of great ideas by everyone in the thread provided an excellent framework for world building.

Inspired by the ideas explored in the thread, I decided to build on this concept and give an impression on the potential ways this world could develop and look like.

@Skallagrim brought together the ideas developed in the thread into a coherent timeline which can be found on page 2. I will post it as a write-up consisting of Skallagrim's master post with additional information that was discussed in the thread along with details on the map itself. Special thanks to the many contributors to the thread @Achaemenid Rome, @Skallagrim, @Cuāuhtemōc, @John7755 يوحنا, @twovultures, and many others.

There were also many divergent and interlocking TL ideas in the thread (contact with West Africa or Trans Pacific trade for example) that may not have been able to be fully fleshed out in a Before 1900 thread alone that I would like to explore at one point. They would make for very interesting worlds on their own.

Most of this timeline is quoted from @Skallagrim. Details and extra content I've added are within brackets [ ].

---

c. 400 AD — Outrigger canoes are developed in Muyil. (The POD.)

c. 400 AD – c. 550 AD — The stability in rough waters of the outrigger canoe is valued for trade along the Caribbean coast. Other Maya city-states soon adopt this new craft. Eventually the canoes are made longer and parts are weaved between to carry greater loads. Fisherman communities from the coastal cities are able to travel further in their trips and carry more of their catch back, reaching Cuba by 550 AD, and from there on solidifying the trade link between Cuba and Yucatan.

c. 550 AD – c. 750 AD — The places where the Maya fishermen visit most frequently become outposts for resupply, and later grow into trading towns. First trading with western Cuba alone, Maya trade posts later emerge all along the Cuban coast, on the Cayman Islands, on Jamaica and at the very west of Hispaniola. Farming communities are established in these emerging towns and they become a new destination and/or source for Maya trade goods.

Eventually the trade becomes highly lucrative to those involved on either side. The trade brings new agricultural products and practices to the Maya heartland, which rapidly spread among the various city-states. Increased wealth and argicultural yield leads to a population boom. In addition, inreasing numbers of people in Yucatan begin to migrate from the cities further south to the northern coastal cities, which have profited most from the Caribbean trade connections. The traditional low-density urbanism of the Maya ends up having some considerable trouble absorbing these developments.

[The transition from Saladoid to Ostionoid occurs in Puerto Rico and Hispaniola. This transition is characterized IOTL by a synthesis of pottery styles of the earlier cultures of the Antilles. The emergence of cultural traits associated with the Taino such as ball courts, plazas, hierarchical chiefdoms and zemi deities are also associated with these changes. ITTL this indigenous Caribbean development is compounded with influence from the expanding Maya linked cultures forming in Cuba. Taking place between 500 and 700 is a thorough synthesis of Maya and Ostionoid cultures and agricultural techniques in the Greater Antilles.]

c. 750 AD – c. 900 AD — Economic and social changes, combined with overpopulation (or rather: a population growth that could theoretically be supported, but cannot easily be absorbed by the existing social model) cause unrest and social problems among the Maya. Increasingly, people moving to the coastal trade cities find there is little place for them there. They move on, along the trade routes, and begin to settle in the trade towns of Cuba, Jamaica and Hispaniola. Later on, these migrants begin to diffuse across the coastal settlements of these islands. Some of the most prominent Maya settlements grow into full-blown cities.

The increased Maya settlement causes demographic and cultural changes on the islands, which is paired with some social upheaval. Despite the inevitable tensions, many have profited from the trade, and continue to profit. Those who have benefitted most are also most closely allied to the Maya settlers. These are also the ones most open to Maya cultural influence, and - handily - the ones who have gained a useful upper hand on their neighbours through the wealth and the cultural innovations that the trade has brought them. Eventually, the migrating Maya simply tip the demographic balance, while also mixing with the native groups allied to them. Both sides adopt cultural practices from the other, and although the resulting culture is heavily dominated by Maya practices and conventions... it is no longer the exact same culture that had existed in Yucatan. (Notably, the trade-based origins and focus of this hybrid culture lends a more prominent role to the merchant class, and causes something of an evolution away from earlier theocratic tendencies.)

[Through sustained and frequent contact with the mainland, the Maya of Cuba form a continuum of trade and knowledge stretching from the Greater Antilles to Central America. The population shift to Northern Yucatan and the Caribbean spreads the Maya cultural sphere and expands the world known to them as a result. Knowledge of the surroundings of the sea soon becomes common to Mesoamerican traders.]

[c.800 AD - Outrigger fishermen bring cultural elements of the Maya and Cuba cultures to Florida. The Gulf stream assures they reach there. The Calusa, who were already a fishing boat building culture adopt them readily. Elements from the Caloosahatchee culture (ropes, causways, canals) from which they belong spread to Cuba and northward along the coast. On the east coast, fishermen returning from the Bahamas spread the outrigger design to the St. John's culture.

The Indigenous peoples of the Florida panhandle encounter Caloosahatchee fishermen more often than before and while trading items from the north for the fishing catch and tools, they begin making outrigger canoes with fibered baskets to travel along the coast and up rivers. The design becomes a staple of the Gulf coast Mississippian cultures and new towns of such type are founded near the shore owing to a small but steady stream of goods from the Caribbean as well as the ability to catch more fish and trade the bounty. As Cuba becomes a source for Maya goods like cotton and cocoa, Floridian traders grow wealthy by bargaining these items up the peninsula. Agricultural communities in southern Florida become much more common than OTL, benefiting from tropical plants that can be grown in a climate closer to home. This, coupled with the abundant marine based resources, allows for larger populations to be sustained.]

c. 900 AD – c. 1100 AD — The Maya, though they rely entirely on oar-driven ships, spread their influence rapidly. As the Caribbean cities continue to grow, new settlements are founded on Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, the Bahamas and on the southern and southwestern coasts of Florida (a region with which the Taino of Cuba already traded). The coastal regions are drawn into the trade network directly. Further inland, large chiefdoms begin to consolidate. These also profit from the trade and from cultural exchange, although they are far more independent from direct Maya influence.

Besides actual establishment of trade posts and any real settlement, there are also more daring expeditions on a more ad hoc basis. Island-hopping isn’t that difficult, and the Taino were already a rather nautical people who used their own canoes for island trade. The emerging Maya island culture essentially expands its trade exactly in the opposite direction from the one the Taino did: tracing the Caribbean arc from Cuba towards Trinidad. (Beyond Puerto Rico, however, this is incidental trade, and not any kind of systematic settlement... yet.)

[By the 1100s outrigger designs have spread to Louisiana owing to the extensive connections that tie the Mississippian culture together. Since pottery, copper, and shells were bartered over land distances far rougher than the coast, the trade route towards the Caribbean (though sporadic compared to core Mississippian sites) is well within the realms of sustainability. It is in this time frame that an outpost at Vieux Carré, New Orleans is founded, originally as a farming-fishing village of the late Coles creek culture. The transition to the Plaquemine culture still occurs but this incarnation has benefited from new boats and subtle trade with growing Florida.]

While hardly a booming trade post at that early stage (the Mississippians are still too far north for any contact to take place), the rich soil of the great river’s delta makes for a highly successful agricultural settlement.

Because the “Carribean release valve” for excess population has worked to migitate the social pressures in Yucatan, the old Maya heartland is stabilising again, and also profits from the trade. Another factor that plays a role in this stabilisation is the increasingly diversified and sustainable agriculture and aquaculture of the Maya polities. The climates and soil types of the various islands that are being settled have sparked a move away from slash and burn monoculture, and towards other alternatives. New crops and new techniques make the whole culture and the entire trade network far less vulnerable to drought, climatological changes, and certain crop blights. The cities of Yucatan also benefit from this. So much so, in fact, that the increased levels op population density become increasingly sustainable. Migration to the islands recedes somewhat (although trade remains booming), and ventures along the Mesoamerican coast begin to be launched instead.

By 1100, the Maya are expanding from Yucatan towards the old Olmec heartland (which has been sparsely populated sinse the Olmec decline of the fourth century BC, and would in Otl remain so until after Spanish colonisation). The old Olmec sites, such as the one at La Venta, become inhabited again... by Maya settlers. On the other side of the Yucatan, some Maya trade posts are established along the Caribbean coast of OTL’s Honduras, while in the south, Mayan influence once again expands through OTL’s chiapas and Guatemala, all the way to the Pacific coast.

Still, despite the flourishing of the old Maya heartland and the expansion of its influence... the economic centre of gravity of the whole trade network is gradually beginning to shift towards the Caribbean islands.

c. 1100 AD – c. 1200 AD — The trade network of the Caribbean Maya gradually expands, as the pattern of trade posts being established and settlements growing around them progressively follows the arc of the lesser Antilles all the way to Trinidad. Ever more daring exploratory expeditions precede the actual settlement, eventually skirting west from Trinidad along the northern coast of South America, and tentatively going east from there as well.

Maya explorers come across South Americans using sails on their boats, and are fascinated by this innovation. Trade-minded as they are, they do not fail to grasp the implications of using ships that do not rely on oars alone. Employing sails would vastly increase the load that Maya ships could carry, and would also make them less dependent on island-hopping for getting around the region. Sails are introduced to Maya ships by eager entrepeneurs around 1100 AD, marking a drastic development that will greatly change the possibilities of nautical trade. By 1200 AD, sails are near-ubiquitous within the Maya trade network.

[The Classic-Postclassic shift sees the center of Maya urban society move not only to northern Yucatan but also beyond towards Belize and coastal Honduras. The moving communities travel along the fishermen routes established centuries earlier. New Maya descended dialects form in coastal central Cuba and Honduras analogous to the Huastec. Accompanying this is the growth of mixed Maya-Arawak and Maya-Honduran societies. These societies, with new Caribbean agricultural techniques spare the southeastern Maya area from becoming irrelevant. Road systems are stronger than the same era of OTL meaning ideas and technologies from the Pacific coast have the chance to spread gradually to the Caribbean. Coastal ports in the greater Antilles flourish while the inland chiefdoms centralize under fortified towns and hamlets.

The 1100s will see sites in the south central Maya area recover while near coastal Belize and Honduras emerge as powerful as their counterparts in the north. The result is the Ulua basin and the Honduran coast becoming the seat of a unique Post Classical urban culture, as well as the encounter with sail/raft making peoples of South America. The era of glory for this new phase in Maya civilization is inaugurated by the invention of the catamaran in the 1200s, inspired by rafts seen on both sides of the isthmus. Their design is combined with the Maya outriggers, creating a vessel that allows traders ro maximise their cargo load. This has such obvious advantages that is rapidly becomes the standard vessel of the trade routes.

Equipped with catamarans and the skills learned from South America open sailing becomes a growing phenomena for the Maya, Cuba, Taino, Chibcha, and Caloosahatche; the later three are more populated and commerce oriented than OTL. Sailors travel directly from Yucatan and Colombia to Jamaica and from Cuba to the Florida panhandle. This new found confidence at sea has emboldened the disparate people of the trade network to ply the coasts and migrate further afield, they can carry more of their cargo physically and culturally. The Post Classic south sends regular trips to Panama,Ecuador and Peru. They pick a bounty of exotic foods, (some nobles have even made gardens and pens), and tools.]

[The Yucatan and Caribbean gradually pull the southeastern Maya and Central American worlds into their orbit, facilitating the diffusion of metallurgy and sails into the island trade network.]

Also by that time, trade posts have been established along the less Antilles, and are beginning to pop up along the Caribbean coast of South America. At this point, sails are mostly still used for coastal plying, but sailing skills are rapidly developing. More daring traders already risk crossing the open sea. Soon, sailing will be so universally embraced that all traders will confidently voyage far out of sight of land.

On the northern edges of the trade network, developments are no less stunning. First of all, various entrepots have been established along the Gulf Coast, more firmly linking the trade posts in Florida to the settlement at Vieux Carré. Besides that, trading posts are also being formed on Florida’s eastern coast. The northerneasternmost trade post, marking the very edge of the Caribbean Maya culture’s influence, is at the mouth of the Altamaha River, near the site of OTL’s Brunswick, Georgia.

Finally, and most importantly, contact is established, around 1200 AD, between the Caribbean Maya culture and the Mississippian culture. Specifically, the Mississippian Plaquemine culture has migrated south, establishing complexes such as Emerald Mound and Grand Village at the site of OTL’s Natchez... and in exploring the region, they have made contact with the Maya settlement at Vieux Carré. Trade links are cautiously established, and a mutual understanding of non-hostility is reached. The Maya esablish a trade post, roughly at the location of OTL’s Medora Site.

While all these exciting developments are underway, the cultural area of the Caribbean Maya people becomes more consolidated. The various chiefdoms are gradually integrated more fully into the trade network, although this takes a number of minor wars here and there. By 1200, the trade empire of the Maya is orderly and at peace. Of course, this trade empire is not really an "empire" at all, but rather a culturally and economically interlinked association of mostly autonomous city-states. In some cases, some of those city states enjoy hegemony over lesser city-states, colonies, and inland chiefdoms (ehich are now much like OTL’s "princely states" of the Raj). There are a number of major cities that tend to dominate their region, and demand loyalty from others in some form or another. But all in all, this is certainly not a rigidly hierarchical empire with one clear capital that calls all the shots, and there is a general understanding of peaceful interaction and free trade.

Within this sprawling and still expanding trade network, the centre of power is now clearly shifting towards the Caribbean islands. The domanant cultural forms are no longer purely those of the Maya (as these once were). The culture has gradually changed as ever more cultures have been absorbed into its sphere. The exact culture, beyond the basic tenets, varies from place to place, but a sense of fundamental common identity and mutual association binds the entire trade network together. (Much like the Greek sense of a common Hellenic identity, even at times when various poleis were most opposed to each other.) The more hybrid culture of the islands has become ever more dominant, and by 1200 AD, the old homeland in Yucatan has mostly been swept into its orbit.

c. 1200 AD – 1300 AD — The use of sails, and an increasing willingness to cross open water, kicks off rapid changes within the trade network. Not only does it solidify the interactions between the Antilles and Mesoamerica to an even greater extent than ever before, but it also brings the harder to reach peripheral areas fully into the network’s orbit. Traders and explorers, both from Trinidad and Yucatan, use sailing vessels to trace the Caribbean coastline of Mesoamerica and South America.

[The recovery of the southeast is nearly, if not totally, complete. The Pacific coast sailors follow the route along the west coast of Central America, retracing the routes through which metalworking diffused. By doing so they encounter skilled craftsmen from the south as well as tying Western Mesoamerica into a more direct trading relationship to northwestern South America. The trade focused Maya and Taino of the Antilles also make use of open sailing to trade across the Caribbean rim and Gulf Coast.]

Establishing entrepots on the coasts of OTL’s Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia, they trade with the native inhabitants and pick up metallurgy techniques and other useful skills and items. Settlements in the region are already utilising ditches, causeways and terraces. The Diquis, Zenu, Tairona, Tierra Alta and an assortment of Panamanian and Colombian highland cultures are gradually drawn into the interaction sphere of the circum-Caribbean trade network.

Sailors from Hispaniola, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, the Lesser Antilles increasingly travel directly to Yucatan, instead of following the arc of the islands (and vice versa). At the same time, ships from the coastal ports of Central and South America ever more frequently cut directly across open water when they head for Cuba etc. — it is truly a new era for trade, and for culture. Ideas are exchanged ever more rapidly.

[One area, once peripheral to the network soon becomes one of it's most important destinations...

Florida's societies continued to grow in size and complexity owing to its warm climate and land connections to the Mississippian culture. They obtained copper via this route since time immemorial, but now there exists a great demand for smelted copper, as tools and currency. Its working became ubiquitous across the Caribbean and Mesoamerica. The Gulf Coast and Florida, connected to abundant copper sources in the Grest Lakes, became a new focus for trading outposts.

The effects of this trade were nothing short of revolutionary. Powerful chiefdoms matured in Florida, the largest based at Big Mound City near Canal point utilized aquaculture in addition to radiating causways to create one of the peninsula's greatest pilgrimage sites. To the west along the Gulf, the Fort Walton, Pensacola, and Plaquemine cultures received Caribbean and Mesoamerican sailors along their fishing villages. They did not come empty handed. Chilies, chocolate, textiles, ornaments, exotic feathers, smelted objects, honey, salt, skins and ceramics were carried on their catamarans. Well recieved by the natives, communities of traders were established within many of the coastal Mississippian sites. Already making outriggers, the Mississippian port towns took to constructing catamarans in their own style and before long were sailing them to the Caribbean, a land beyond the sea with cities and treasures beyond imagination.

The Gulf Coast also experiences meteoric growth in urbanization and specialization. A series of trading towns pepper the bays, expanding from the already prominent boat building villages. These urban centers act as middlemen to the more northerly parts of the southeast, providing a link to the most exotic tropical goods through their seaborne connections.

Influence also comes from the north in the form of a chiefdoms based at Moundville and Etowah in Alabama and Georgia. One of the largest Mississippian sites, Moundville appears to have repeatedly interfered in the affairs of the Pensacola culture of the coast. At the Bottle Creek Mounds, legends and texts tell diplomatic and militarily relationships to the north. The Lake Jackson Mounds also show trading relationships to the north through Etowah, the latter sitting along the trade route to copper sources in the Cumberland Plateau. It was through these means that copper smelting and agricultural techniques made their way into the interior. Such interactions went a long way towards tying the northern parts of the South Appalachian Mississippians into the Gulf Coast's Pan-American economy and the Maritime Horizon cultural sphere.

This is corroborated in the archaeological record by the appearance of copper smelting workshops not only at Moundville, but also at Etowah, the latter sitting along the trade route to copper sources in the Cumberland Plateau.]

By controlling the distribution of these goods to the interior, the Gulf chiefs grew famously wealthy and one site would be the wealthiest of them all...

The Vieux Carré site of Plaquemine culture grew exponentially thanks to its fertile soils and direct trade with the south. A new archaeological horizon begins around the 1300s. Characterized by a dazzling array of Mesoamerican and Caribbean artifacts, large mounds, ditches, canals, and a large population, the stylistic types Vieux Carré expand northward. Cahokia's influence meanwhile spreads southward, eventually fully connecting the copper sources far to the north to the Caribbean.]

Vieux Carré is blooming into a major city, while lesser boom towns pepper the Gulf coast from the site of OTL’s Galveston to Florida. The sea lanes now loop the Gulf, while sailors also travel across open sea. The delta dwellers, once living on the periphery, now have far more direct contact with the rest of the trade network. And so much the better. With trade goods like textiles, chocolate, chilies, exotic stones and feathers available to the Maya merchants, the trip to the mouth of the Mississippi is well worth the cost. The Mississippians to the north are eager to buy, to learn, to exchange goods and knowledge. The Plaquemine culture, growing immensely rich by being the middle man between the Maya and the other Mississippians, are eager to share their canal building techniques with the Maya settlers. This allows the booming city at Vieux Carré to become a masterpiece of water management, ensuring that its teeming masses keep their feet dry.

Among the Mississippians, wealth derived from the Mesoamerican-Caribbean trade gradually allows more centralised command structures to form, along with a greater opportunity to manage infrastructural works. The same goes for the city at Vieux Carré. The two cultural spheres continue to learn from each other, and even adopt some of each other’s cultural tenets. Nobably, the mississippians adopt certain agricultural practices from their trade partners, which ultimately brings them a more versatile and stable supply of food.

[Some other Plaquemine sites share Vieux Carré's unique iconography. Most prominent are warrior emblems and effigy vessels of priests and priestesses. This indicates the rise of one of the most powerful of Mississippian chiefdoms. It is called by its inhabitants "Ku-Hanan", based on the Chitimacha words water and house respectively. The name derives from the large harbors of catamarans, canoes and rafts near its largest canals. Some settlements dominated by the Ku-Hanan Chiefdom become specialized centers for manufacturing and distributing goods. Copper, river canoes and rafts, catamarans, textiles, and pottery workshops, and plantations across the Plaquemine culture testify to the chiefdom's influence.

Controlling the diminished hunting grounds, maintaining workers in its various sectors, the lucrative copper trade, wood for boats, tropical/subtropical fibers for fishing and sails leads to the rise of a military of elite warriors and religious means of ensuring legitimacy. Ku-Hanan comes to dominate other local chiefdoms as vassals, who pay tribute in traded items and captives to the paramount. The late 1400s sees the Plaquemine and parts of the surrounding cultures united under Ku-Hanan hegemony. In fact it's name had a reputation across the gulf of Mexico and into the Ohio river, spoken by oral historians and even bearing a gliph of it's name in a Huastec codex.]

While not incredibly common, no Caribbean merchant would by this point be surpised to bring Mississippian emmisaries to Cuba, nor is it unheard of for Maya dignitaries to occasionally venture up the Mississippi— occasionally even as far north as Cahokia.

.....

[The 13th century marks the beginning of what historians of TTL call the Maritime Horizon. This archaeological horizon represents a unique phenomenon in that it is the first indigenous culture to span a considerable portion of both continents, thus becoming pan-American in scope. The Maritime Horizon is not marked by a single dominant cultural trait, but by the (synthesis) of elements from many societies surrounding the seas. Though many cultures and ideas will come to define this "maritime age" a few early traits are noteworthy to separate this era from the one immediately preceding it. The first is a demonstrated ability (and preference if the records left behind at Maya trading enclaves are to be understood) for sailing into the open sea. This period features an active policy on the part of Maya descended traders to not only seek trading opportunities along established sea lanes but also to find new ones.

Another defining early trait was the presence of smelting technology, especially with copper alloys. These technical skills proved extremely useful both with regards to the creation of art and utilitarian use as can be seen in later times by the metal tweezers in Hispaniola, the cast molded Mississippian copper plates, and the implements used in ship making.

The early defining elements of the Maritime Horizon merged together in an arc stretching from northwestern Colombia through Central America and esast to Puerto Rico. This core would then absorb a plethora of ideas from contributing cultures as they were brought into the interaction sphere.

In spite of the established seaborne trade routes, the first great navigators of the Maritime Horizon were based in the Pacific rather than the Caribbean. The mariners appear to have followed the coastal routes through which metalworking was introduced from the south.]

With open sea sailing now the norm, long distance expeditions along the coastline of the Americas are being attempted in the early [13th] century. These are prestige undertakings by which the various great cities attempt to outdo one another. The always-present possibility of finding new trade partners also plays a role, of course. The most promising of these expeditions, undertaken at the end of the 13th century, is the daring journey down South America's west coast. A particularly enterprising group of wealthy merchants from a Maya city on the Pacific coast, determined not to be outdone by the more prominent teaders of the Caribbean, orders an unprecedented expedition to the far south. Travelling beyond Panama, the exceedingly experienced marined hired to carry out this feat reaches the urban centers of Ecuador— with their own impressive naval traditions and their well-established trade network up to lake Titicaca. Stopping by the Sican, Chimu, and Chincha cultures, the Maya crew ultimately brings back the most exotic textiles, smelted tools (the Chimu being known for their utilitarian bronze objects), hallucinogens, animals, and foods.

This development causes a major boom in the establishment of new settlements on Mesoamerica’s Pacific coast in the middle of the [13th] century, and lucrative trade with the various cultures to the south. To facilitate the transportation of goods, the leading merchants of various major cities eventually begin to discuss a wild idea: a [series of] canals, to be cut across the isthmus of Panama. (And this notion is not utterly ridiculous: the Egyptian Canal of the Pharaos, first cut in the sixth century BC, was 35 miles long, whereas OTL’s Panama Canal is 48 miles long.) [As these cities mature, they each add their own contribution to the network of causways and canals.]

....

[Northern Colombia, as an early nucleus of catamaran construction, begins the transformation into a trading nexus. The Tairona emerge as the foremost seafarers of the region, uniting the coast economically with the Maya trading communities. Already renowned builders of terraces and paved stone roads, the Tairona were quick to add Mesoamerican architectural styles to their already sophisticated works. To the immediate west, the 1100s IOTL featured a decline in the waterworks of the Zenú, the population subsequently relocating to the highlands from the lowlands. ITTL a shift southward still occurs, but lucrative trade to Mesoamerica and the Antilles (obtaining goods such as vanilla and cacao) gives a great incentive to hold the coast in their orbit and integrate it to the highlands. This is accomplished through the construction of roads and canals as well as sustained merchant activity from the Tairona. In the coming centuries the cultures of Colombia would rise to become among the most influential contributors of the Maritime Horizon through bridging the Andes to the Caribbean and beyond.

.....

Owing to a long history of seafaring, it should come as no surprise that the peoples of Ecuador would take full advantage of new vessels capable of tackling the open ocean. It was sailors from Ecuador, plying the coast on balsa rafts, that brought metalworking to Central America. Building on old tradition, the Manteño used the catamarans to ply their old trade routes with larger cargo capacity than what was possible before. Trade to the north, while not infrequent, was often indirect..at least until a Maya voyager from the Pacific coast of Guatemala made landfall in the Manteño heartland. Bringing with him exotic goods such as feathers, cocao, and honey, the Maya Voyager made quite an impression on the Manteño leaders. They took great interest in obtaining these treasures directly. Likewise the Maya Voyager returned from his trip with the wealth of the Andes. It was the beginning of a fruitful relationship.

......

With open ocean voyages becoming a universal phenomenon, a great synthesis is underway. Arising from the connected trade routes traveled by the peoples of the Maritime Horizon is an ever expanding economic web. This is referred to as the Pan-American Interaction Sphere by archaeologists, an exchange network stretching from the Andes to the Mississippi basin. Crafts, tools, art styles, exotic materials, crops, agricultural systems, and technologies where brought together, culminating into in a wide-ranging cultural flowering that transformed all the societies touched.

Peoples from Mesoamerica, the Caribbean, Central America, the Andes, the Gulf Coast and the Mississippi basin over time accumulated knowledge of each other, linked together in a pan-American world.]

c. 1300 AD – 1491 AD — By the 14th century, the Caribbean Maya culture has almost reached its greatest extent. It is a vast collection of thriving market centers, all across the Antilles, the Bahamas, Florida, the northern Gulf Coast of North America and the Caribbean coasts of Mesomamerica and South America. All these regions have been more or less swept up into the cultural sphere of the Caribbean Maya. The population of the larger region is considerably higher than OTL. Politically, the region is a mosaic of cities, confederations, towns, kingdoms and chiefdoms. The culture is highly diverse, varying from place to place in a number of loose groupings, but there are certainly cultural traits that bind them all together; a Caribbean equivalent of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, that synthesizes all the interacting societies. Ceremonial pilgrimage sites, ball games, cults and recreational foods... all shared across the sea lanes.

Of late, the Maya settlements on the Pacific coast (in OTL’s Chiapas and Guatemala) have begun to send out even more trade expeditions along the coastline, and not without success. All of Mesoamerica has been thoroughly tied into the trade zone and its cultural sphere. The time is ripe to learn of what lies beyond...

Mississippians and Florida

The maturation of centuries of direct contact with Mesoamerica, the Caribbean, and South America has transformed the Gulf Coast cultural region. What was once an area characterized by scattered fishing villages has given way to a thriving littoral of urban centers where the most exotic materials found in the hemisphere are exchanged. The trading towns, pilgrimage centers, and port cities that rim the shore represent the immense wealth of this new society, which has rapidly become the most densely populated area of North America north of Mexico. The Mississippi basin has emerged as a highway for economic and cultural influence from all over the Americas to permeate through the continent. The Mississippi delta is one of the great nexuses of the Pan-American Interaction Sphere and thus a sizably urbanized locale.

The cities of Louisiana are all under the hegemony of Ku Hanan and recognize the ruler as sovereign over their interactions. The cities have their own branches of the Ku Hanan clans in their elite positions, ranging from priests, to artisans and military governors. Crisscrossed by canals and mounds, the city of Ku Hanan is one marked by a massive system of earthworks and port areas. The need to maintain the function of Ku Hanan's canal system, workshops, and shipyards has fostered the growth of the first writing system of the Mississipian culture. Like virtually all writing styles of the Maritime Horizon, the Ku Hanan scrip is derived from that of the Maya. In this instance the script is reinterpreted in the Chitimacha language which has become the lingua franca of the former Plaquemine culture and the Gulf Coast. Chitimacha has gathered a great many loan words from the gulf and Mesoamerica, particularly Mayan and Totonacan.

The cultural traits encompassed by Ku Hanan have transferred across much of the Mississippi watershed, with it's peoples gradually absorbing innovations into their own production networks. This process has lead to the development of comparable political and economic units. A textbook example is the use of smelting technology, which was adapted into the millennia old copper working tradition stretching to Hopewell days. Smelted copper alloys were utilized for new experiments in art style, form, and function across the basin. Ritual plates and statuettes were created using the lost wax casting method while axes of copper and bronze were used ritually and technically depending on the location. Many items manufactured in Ku Hanan and other Mississipian sites have been found in burials as far away as southern Mexico and Peru.

By the 1400s the realm Ku Hanan still holds the position as the most populous polity and urbanized area of the Mississipian culture and will for some time. This doesn't mean that the runner ups are stagnant however. To the east are city states built from the Pensacola, and Fort Walton cultures. They have undergone similar expansion in organization and population, supplying exotic goods to the southeastern interior. Upriver from Louisiana and north of the Gulf are chiefdoms that have also benefited from introduced plants, animals, and technology from as far as the Andes. Though Cahokia has still declined, it's hegemony over other Middle Mississippian sites is being replicated by successor chiefdoms. The demographic and cultural weight of Ku Hanan remains very strong to challenge but with a more favorable climate for Andean crops the Middle Mississippian region may regain the limelight.

Florida's landscape is characterized by city-states and regional kingdoms developed out of a three way amalgam of local, Mississippian, and Cuba-Maya influences. The transition towards urbanism in Florida is somewhat similar to that of Cuba, with communities subsisting through intensive agriculture gradually growing over time. Florida provides a coastal route to the Mississippi delta and Atlantic seaboard during times when weather makes it too hazardous to sail in the open ocean. Florida's polities function through a kind of ritual hegemony, where influence is spread via trade, cultural works, and the maintenance of pilgrimage centers.

Mainland Maya Area

The Southern Maya Area is one of the three great ship building regions of Mesoamerica, sharing this title with Yucatan and Veracruz. Contact with other societies that rim the Pacific is a common occurrence. This area was the source of the first missions to South America and the inhabitants have not lost their exploratory spirit.

The coastal cities are tied economically to southern Mexico, Isthmo-Colombia and Western South America, with Maya communities inhabiting all these areas. They have managed to build a thriving trading society and bring back plenty from their voyages. The introduction of a variety of Andean foodstuffs has lead to a growth in urbanism within the highlands, with the Chuj forming a hegemony over highland sites.

The coastal cities of the southwest are slowly falling into the Chuj orbit but those of the southeast are allying themselves with the Lenca and Pipil to resist this trend. The Lenca region is another hotbed of the new Maya civilization, owing to more productive agricultural techniques and a series of polities that have managed to sustain trade between both shores of the isthmus. Consolidating into a single state, the Lenca are have become one of the strongest players in the mainland Maya world.

The political scene of Belize is lead by a trading empire built by the Mopan people. They prefer to leave the squabbles of their neighbors alone and focus more on keeping their network of posts along coastal Honduras and Nicaragua functioning properly.

Mesoamerica outside the Maya

The Mixtec and Zapotec homelands have benefited greatly from trade and fishing with the cultures surrounding the Pacific. Merchants from as far afield as Peru and Ecuador are a common sight and those of the Maya world more common still. The Mixtec and Zapotec were among the first Mesoamericans (excepting the Maya) to practice the intensive cultivation of uniquely Andean crops. As such, their demographic growth has underpinned their ascension in the political scene of central Mexico. The Mixtec are currently the leading members of the relationship, though the culture can be considered to be thoroughly blended.

Western Mexico's current hegemon is a state lead by the Náayeri, the Cora people. The region was originally divided into a mosaic of local cities, with coastal ones serving as stepping stones to Oasisamerica. As sea borne trade intensified, the Náayeri found themselves along the main route to copper and turquoise sources from the north. This has been used to increase their clout with polities to the east. Náayeri architecture is heavily inspired by the Teuchitlan tradition, known for rounded step pyramids. This architectural style has gained some popularity with a few of the Oasisamerican settlements.

The Náayeri would have reached central Mexico if not for the league of Purépecha cities. These cities, in conjunction with their coastal neighbors have kept the Náayeri and their Chichimec allies from central Mexico for now. These contests are notable for the use of bronze weapons and tools in combat.

Central Mexico features three great powers, the Hñähñu of the north, Huejotzingo to the east, and Azcapotzalco to the southwest. The Hñähñu kingdom represents a resurgence of Otomi power in an era otherwise dominated by Nahua peoples. The Hñähñu are primarily defensive in their relations, though this is slowly changing. The rulers have recently adopted a policy of allying with downtrodden, displaced peoples and their cities, providing relative safety and peace in exchange for military, government, and agricultural services. This has endeared many to the Hñähñu cause as a result. Thus the Otomi have perhaps the most loyal allies of central Mexico and pro Hñähñu revolts a cropping up more and more frequently.

Huejotzingo and Azcapotzalco were originally the two largest political entities of central Mexico, with a relationship that could best be described as mutual hostility. Ebbs and flows where one city held many others under their loose hegemony was a steady feature of the early 1400s until Huejotzingo finally succeeded in capturing the tlatoani of Azcapotzalco. Determined to eliminate Azcapotzalco as a threat, the ruler of Huejotzingo systematically replaced the royalty of the city with that of his own and garrisoned Azcapotzalco's closest allies with elite troops. Unfortunately, the altepetl surrounding both polities did not appreciate loosing the opportunity to play both sides against each other and are now in the process of revolt. The Tepanec and Mexica are currently offering overtures to Hñähñu in their struggle, while the rulers of Huejotzingo are trying their best to centralize their realm in order to keep what they fought so hard to obtain.

Veracruz has emerged as the new hotbed for Mesoamerican sailing outside the Maya region. Vessels carrying items from across the Mississippi make port along the eastern coast Mesoamerica and vice versa. The art styles of the Mississippi delta and Veracruz share much in style, with copper plates becoming very popular with the nobility in Veracruz. Far flung trade has worked to the advantage of the Totonacs, who have used the revenue and communication routes to create a confederation of eastern cities. This Totonac led alliance is more than capable of fending off expansionary efforts from central Mexico.

The Totonac share the coast with the Huastec to the north and a collection of Maya and Nahua cities to the southeast. The Huastec were relatively late in adopting shipbuilding techniques compared to other coastal peoples but took a much more proactive approach to supplying the routes. Establishing small communities along the coast of northern Mexico and Texas, the Huastec sail the shore until they reach the Mississippi delta. The cities are dependant on the Huastec heartland to keep afloat, excepting a growing settlement at the Rio Grande.

The old Olmec heartland was resettled with Maya traders who utilized new agricultural systems and trade routes to revitalize the region. The intensive activity has attracted a new wave of Nahua migrants to the coast, who have also absorbed the cultural elements of the people they encountered.

Oasisamerica

The changes brought about from the Maritime Horizon could not stall the decline of the Oasisamerican cultures. Afflicted with drought and stressed by unmanageable floods many of the larger centers were abandoned. Migration to adjacent valleys still amicable to cultivation continues even after Mesoamerican merchants arrived by sea.

The villages of the Hohokam culture have shifted to Gila basin, an OTL transition that was encouraged somewhat ITTL by the influx of exotic Mesoamerican goods. By sailing along the Gulf of California, mariners from western Mexico have gained direct access to valuable turquoise and copper sources as well as an opportunity to share ideas with the southwest. The Oasisamerican cultures are making a subdued recovery with the introduction of new crops and smelting techniques.

Caribbean and northern South America

By the late 1400s the Caribbean has truly come into its own as a nexus for trade. Maya descended voyagers have completely traced the Antilles from Cuba to Trinidad and the various seafaring peoples they encountered have integrated the boat building technologies into their lifestyles and economies. Urbanization and political consolidation has gathered apace in the Antilles and the Caribbean rim owing to direct connections from Mesoamerica, the Gulf Coast, Central America and the Andes. The Maya and Taino of the Greater Antilles are organized into a number polites based around trading cities and fortified towns. They share these centers with numerous other peoples from across the Americas.

The cosmopolitan nature of the Maritime Horizon can be said to be most accentuated in Northern South America. Here the coastal areas and islands are peppered with cities and towns founded by peoples touched by the Maritime Horizon exchange network. An inhabitant of these settlements could easily have a conversation with a persom of Maya, Chibchan, Taino, Carib, or Mississippian descent.

The principle powers of the Caribbean are Ho’ol pol Kan ("Head of the Snake") and Aakpeten (Turtle Island) of western Cuba and Jamaica respectively. These polities have created leagues centered around themselves. Unwilling to challenge each other directly, these rivals instead have engaged in a series of proxy conflicts between tributary rulers and governors. These tensions dominate the political scene of Yucatan and Cuba.

Aakpeten was unified by an oligarchy whose members permeated throughout the island until their collective weight translated to an active political policy beyond the landmass. This process has been repeated in the coastal towns of Yucatan, Cuba and Hispaniola where many local nobles have connections to the ruling families of Aakpeten.

The the city of Ho’ol pol Kan is located at Consolación del Sur. Ho’ol pol Kan's dominance of the Yucatan channel has brought it great wealth. Sitting on the trade route between Central America, South America, and the Gulf Coast, Ho’ol pol Kan has built a trading empire with subject cities in Florida and western Yucatan. Ho’ol pol Kan was close to unifying northern Yucatan until a coalition of cities gained naval support from Aakpeten. Ho’ol pol Kan, dispite being the larger of the two alliances, is less coherent than Aakpeten, the latter benefiting from control of the entire island of Jamaica. The foreign support of Ho’ol pol Kan's enemies on the Cuban mainland poses the greatest threat to the city.

Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, and the Lesser Antilles are a mosaic of city-kingdoms and statelets of Taino, Island Carib, and Maya origin, with a strong Pan-American component. With such a diverse array of peoples exchanging ideas, the culture of the Antilles is one that trends toward experimentation. The area is a hotbed of changing ship designs, building techniques, and political organizations. Rigging styles and sail shapes are being developed through a process of trial and error, while cities are lead by caciques and cacicas who fulfill roles ranging from explorers to military leaders. The latter role has grown much more common as not all Maya and especially Carib have arrived to the island peacefully. In Puerto Rico specifically, Carib raiding clans have come to control half of the island. The Tainos of Puerto Rico were originally on a trend towards a chiefly oligarchy with signs of nascent republicanism. The Caribs of the east have absorbed these aspects of society and redirected them towards a kind of meritocracy based on military prowess, where the most successful raiders are elected to lead the latest assault. This ideology is spreading throughout the Carib dominated parts of the trade network, slowly increasing the organization and effectiveness of the Island Caribs and allowing them to take even larger cities previously beyond their grasp.

....

The centuries following the 1200s features the consolidation of a regional state in the Tairona heartland. This process is initially indicated by standardized artwork, massed produced ceramics and later by stela and glyphs marking domains ruled by Tairona monarchs. The glyphs are demonstrably descended from Mayan, made in a unique Colombian style, making it the oldest written attestation a Chibchan language. The cities of this state all share a similar architectural style, especially administrative buildings, indicating a degree of direct control unseen before in the Isthmo-Colombian region. Other forms of standardized works include the ceremonial ball game common throughout Mesoamerica as well as plazas for chunky (a Mississippian game), and batey (a local one). These games have taken on an almost Olympic feel, where sporting folk are rewarded handsomely for mastering all three.

The rulers of this polity were called Makú (Lords), and it's domain Makú-Kággi, The Lord's Earth. Information on the early Makú-Kággi state derives from texts written by it's priests as well as Maya and Pochteca merchants who frequented the trade routes the Makú sought to control. These records state that Makú-Kággi began as a union between the Tairona and Zenú wherein the two groups agreed to aid each other in restoring their canal systems after a major drought. This confederation soon grew into a redistributive network where food surplus, trade goods, and ritual objects were concentrated and presented to local urban centers. Eventually, the Tairona and Zenú became one and they connected their realms through the maintenance of their already extensive network of roads and canals, centralizing continuously afterward.

To protect their trading cities and combat piracy the Makú-Kággi have assembled the largest navy in the hemisphere, a massive fleet of catamarans used for both trade and war. The Makú-Kággi navy is in fact large enough that even the fearsome pirating Carib alliances tend to steer clear (though some have joined as a sort of royal guard to the Makú). The funds for maintaining the fleet are obtained through taxation of trade across the cities of Panama, creating a feedback loop wherein the more stable the trade, the stronger the fleet and thus the protection of trade.

The greatest challenge of the Makú is coordinating the fleets of the Caribbean and the Pacific to maximize safe passage for merchants from Yucatan, Peru, and the Antilles. Originally the strategy was to garrison two cities (Panama, and Colon) on both ends of the isthmus and link them via an extensive system of causeways and canals. This system did not create a continuous stretch of water between the two seas but did serve as the foundation for such a structure later. The Makú responsible for linking the canals together was Kuisbángui (reigned 1398-1419), named after the Tairona lord of thunder. Kuisbángui is said to have embraced the idea of a continuous canal after hearing the idea from a prominent pilgrim during his coronation. To complete the project, the greatest and brightest of the Americas were brought together, engineers from as far as Louisiana, Mexico, and Peru. The Canal of the Snake, as the project was to be called, became one of the largest earthen structures of the hemisphere. In fact, it is one of the only cross referenced structures of indigenous tradition, mentioned not only by the Maya but also by the Taino, Manteño, and Caribs.

Makú-Kággi is currently attempting to assert hegemony over the city-states of Costa Rica with the coastal cities either governed directly or as tributary allies. The urban centers of the coast have significant foreign communities while the interior is fully in the hands of the locals.

Andes

Following the end of Wari and Tiwanaku, the Andes have entered a new period of urban development. Regional identities have grown stronger and with it a willingness to experiment with ideas from the past as well as the present. From the 1200s onwards these societies were increasingly drawn into the expansive world of the Maritime Horizon. This new period features the growth of cultural, economic, and political ties between the Andes and the Isthmo-Colombian, Caribbean and Mesoamerican regions. The integration of these societies into the Pan American exchange network transformed the lifestyles of the coastal peoples. With excellent ocean going ships they were able to communicate with each other faster and more frequently. There also grew a greater capacity to fish in the productive waters of the Humboldt current, a major draw for the inhabitants of the coastal deserts...

As the Manteño merchant clans pursued a role as middlemen traders they established themselves in quarters along various coastal ports. Setting up shop in the domains of the Sican, Ica, and Chincha, the Manteño spread (wether purposeful or not) the knowledge of their routes and techniques.

It would be the Chincha that would propel the sea going traditions to new heights. An urbanized people of exceptional trading experience throughout the Andes, the Chincha merchant lords spread their network to the far flung regions the Manteño found too distant to reach. Chincha settlements peppered the coast of Chile acting as springboards to the ocean and interior. Traversing the shores beyond the Atacama, Chincha sailors encountered fearsome peoples of the far south. While some were hostile to the newcomers, others were more than willing to cooperate in exchange for tools, and precious goods. Many of these peoples, known to us as the Mapuche accompanied the Chincha on their way back north as mercenaries, serving in the armies of both Chincha and Manteño lords....

The Manteño-Chincha duopoly discovered a number of Pacific islands on their fishing and exploratory missions, including the Galapagos, San Felix, and San Ambrosio. Sailors created elaborate charts to map the stars and currents on their trips. Their hegemony however came under threat in the late 1300s when the rulers of Chimor forged an alliance with the trading clans in their territory to seize the ports and valleys of the coast. The campaigns of the Chimu eventually reached the Manteño and Chincha heartlands and soon the traded artifacts featured art styles associated with Chimor hegemony.

The last Chincha lord was said to have forseen the coming of the Chimu while on pilgrimage to the oracle of Pachacamac and chose to flee to the west where people too built double hulled boats. This was initially dismissed as legend by chauvinistic historians who thought little of the indigenous peoples. The more focused research of today has brought to light the contacts between the Americas and Polynesia as artifacts and plant remains revealed not only meetings but transfers of knowledge as well. While the last lord of the Chincha was not the first or last of the Andean sailors, his story is a testament to the confidence of these peoples in the open ocean.

Chimor's hegemony proved to be short lived. A succession struggle with claimants backed by differing merchant clans and nobles reduced Chimor to it's base territories while the coastal polities it captured reasserted their independence. These areas were heavily influenced by Chimor's art and organization, using these models to centralize their resources.

By the 1400s, highland powers are making moves towards the coast. This is an active policy for the Wanka and Lupaca. The Wanka have united many fortified towns under their banner and are currently contesting the mountains with the Quechua of Qusqu. The homelands of the Chanka have borne the brunt of these conflicts, being situated between these two powers.

The Lupaca, an Aymara people , were more fortunate in their coastal ambitions, not facing nearly as organized a resistance as their northern neighbors. They have managed to incorporate the Chincha trading settlements peacefully, striking a deal where the Lupaca protect the traders interests overland while the traders supply the Lupaca with the bounty from the sea. The Lupaca have solidified their land trade through the construction of forts along the major caravan routes, an idea borrowed from the Wari. These forts also serve as a buffer against Qusqu raids from the north and rival Aymara kingdoms from the east.

The maturation of centuries of direct contact with Mesoamerica, the Caribbean, and South America has transformed the Gulf Coast cultural region. What was once an area characterized by scattered fishing villages has given way to a thriving littoral of urban centers where the most exotic materials found in the hemisphere are exchanged. The trading towns, pilgrimage centers, and port cities that rim the shore represent the immense wealth of this new society, which has rapidly become the most densely populated area of North America north of Mexico. The Mississippi basin has emerged as a highway for economic and cultural influence from all over the Americas to permeate through the continent. The Mississippi delta is one of the great nexuses of the Pan-American Interaction Sphere and thus a sizably urbanized locale.

The cities of Louisiana are all under the hegemony of Ku Hanan and recognize the ruler as sovereign over their interactions. The cities have their own branches of the Ku Hanan clans in their elite positions, ranging from priests, to artisans and military governors. Crisscrossed by canals and mounds, the city of Ku Hanan is one marked by a massive system of earthworks and port areas. The need to maintain the function of Ku Hanan's canal system, workshops, and shipyards has fostered the growth of the first writing system of the Mississipian culture. Like virtually all writing styles of the Maritime Horizon, the Ku Hanan scrip is derived from that of the Maya. In this instance the script is reinterpreted in the Chitimacha language which has become the lingua franca of the former Plaquemine culture and the Gulf Coast. Chitimacha has gathered a great many loan words from the gulf and Mesoamerica, particularly Mayan and Totonacan.

The cultural traits encompassed by Ku Hanan have transferred across much of the Mississippi watershed, with it's peoples gradually absorbing innovations into their own production networks. This process has lead to the development of comparable political and economic units. A textbook example is the use of smelting technology, which was adapted into the millennia old copper working tradition stretching to Hopewell days. Smelted copper alloys were utilized for new experiments in art style, form, and function across the basin. Ritual plates and statuettes were created using the lost wax casting method while axes of copper and bronze were used ritually and technically depending on the location. Many items manufactured in Ku Hanan and other Mississipian sites have been found in burials as far away as southern Mexico and Peru.

By the 1400s the realm Ku Hanan still holds the position as the most populous polity and urbanized area of the Mississipian culture and will for some time. This doesn't mean that the runner ups are stagnant however. To the east are city states built from the Pensacola, and Fort Walton cultures. They have undergone similar expansion in organization and population, supplying exotic goods to the southeastern interior. Upriver from Louisiana and north of the Gulf are chiefdoms that have also benefited from introduced plants, animals, and technology from as far as the Andes. Though Cahokia has still declined, it's hegemony over other Middle Mississippian sites is being replicated by successor chiefdoms. The demographic and cultural weight of Ku Hanan remains very strong to challenge but with a more favorable climate for Andean crops the Middle Mississippian region may regain the limelight.

Florida's landscape is characterized by city-states and regional kingdoms developed out of a three way amalgam of local, Mississippian, and Cuba-Maya influences. The transition towards urbanism in Florida is somewhat similar to that of Cuba, with communities subsisting through intensive agriculture gradually growing over time. Florida provides a coastal route to the Mississippi delta and Atlantic seaboard during times when weather makes it too hazardous to sail in the open ocean. Florida's polities function through a kind of ritual hegemony, where influence is spread via trade, cultural works, and the maintenance of pilgrimage centers.

Mainland Maya Area

The Southern Maya Area is one of the three great ship building regions of Mesoamerica, sharing this title with Yucatan and Veracruz. Contact with other societies that rim the Pacific is a common occurrence. This area was the source of the first missions to South America and the inhabitants have not lost their exploratory spirit.

The coastal cities are tied economically to southern Mexico, Isthmo-Colombia and Western South America, with Maya communities inhabiting all these areas. They have managed to build a thriving trading society and bring back plenty from their voyages. The introduction of a variety of Andean foodstuffs has lead to a growth in urbanism within the highlands, with the Chuj forming a hegemony over highland sites.

The coastal cities of the southwest are slowly falling into the Chuj orbit but those of the southeast are allying themselves with the Lenca and Pipil to resist this trend. The Lenca region is another hotbed of the new Maya civilization, owing to more productive agricultural techniques and a series of polities that have managed to sustain trade between both shores of the isthmus. Consolidating into a single state, the Lenca are have become one of the strongest players in the mainland Maya world.

The political scene of Belize is lead by a trading empire built by the Mopan people. They prefer to leave the squabbles of their neighbors alone and focus more on keeping their network of posts along coastal Honduras and Nicaragua functioning properly.

Mesoamerica outside the Maya

The Mixtec and Zapotec homelands have benefited greatly from trade and fishing with the cultures surrounding the Pacific. Merchants from as far afield as Peru and Ecuador are a common sight and those of the Maya world more common still. The Mixtec and Zapotec were among the first Mesoamericans (excepting the Maya) to practice the intensive cultivation of uniquely Andean crops. As such, their demographic growth has underpinned their ascension in the political scene of central Mexico. The Mixtec are currently the leading members of the relationship, though the culture can be considered to be thoroughly blended.

Western Mexico's current hegemon is a state lead by the Náayeri, the Cora people. The region was originally divided into a mosaic of local cities, with coastal ones serving as stepping stones to Oasisamerica. As sea borne trade intensified, the Náayeri found themselves along the main route to copper and turquoise sources from the north. This has been used to increase their clout with polities to the east. Náayeri architecture is heavily inspired by the Teuchitlan tradition, known for rounded step pyramids. This architectural style has gained some popularity with a few of the Oasisamerican settlements.

The Náayeri would have reached central Mexico if not for the league of Purépecha cities. These cities, in conjunction with their coastal neighbors have kept the Náayeri and their Chichimec allies from central Mexico for now. These contests are notable for the use of bronze weapons and tools in combat.