Chapter 60: Imperial Russian Army, Part IV: The Resistance of the Old Guard

Imperial Russian Army, Part IV:

The Resistance of the Old Guard

War Minister Kuropatkin felt from day one in his new job, that his duty was to finish the job his great role model had started decades earlier. For Kuropatkin it was clear that his paragon, the great Miliutin had correctly understood the key to the survival and greatness of Russian Empire: an educated, competent officer corps. The reform efforts started by Miliutin had thus focused on providing leadership for the army based on merit; from the start to the end of his tenure he had fought the strong aristocratic privileges that allowed incompetent officers to rise to high positions. This conflict, between merit and noble privilege, was still a key issue in Russian officer training when Kuropatkin took office. Kuropatkin greatly admired Miliutin, and inspired by his predecessors example he pushed further reforms in officer education with considerable political and administrative effectiveness. But whereas the great Miliutin had had the backing of the reforming tsar Alexander II, Kuropatkin had to deal with Nicholas II, who dogmatically defended the privileges of the aristocracy, the old generals and the “parade culture” that characterized the imperial army in general.

The battle over the inclusion of lectures about the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 into the curriculum of the General Staff Academy is a good example of the kind of systemic resistance the reforms promoted by Kuropatkin and his patron Grand Duke Nicholas faced. The Russo-Turkish War was the most recent war where Russia had fought, and the first one to be fought by the army since the reforms stared by Miliutin. Russian military-scientific interest towards the war had been considerable since it's conclusion, and both Kuropatkin and Grand Duke Nicholas had published books about the subject. So when Coloniel E.I. Martynov announced his intent to organize a series of lectures based on the work of a military-history commission that had been working on the war’s history for twenty years without publishing any findings before this, the higher ranks of the Russian officer corps naturally expressed a great deal of initial interest. The initial curiosity was met by a shock, when it became clear that Martynov would not hesitate to point out that the meddling of the Grand Dukes in decision-making had been behind several of the key operational failures in the war. Because members of the Imperial family still dominated the high command of the Russian army in 1877-78, such lectures, no matter how close to the truth, were political dynamite, and initially it seemed clear they could not and would not be tolerated at the Nicholas Academy. But after Kuropatkin consulted Martynov and pressured him to drop the criticism to Grand Duke Nicholas, the controversial lecture courses were eventually started in 1907, and turned into an annual course of the history of the war in the following year. Finally Russian officers could learn from their latest military encounter, instead relying on histories of European conflicts and the US Civil War.[1]

These kind of obstacles to Kuropatkin’s plans came from the legacy of officer education system inherited from General Mikhail Dragomirov, who had had both Academy teaching experience and a formidable field service as the commander of the important Kiev Military District and as the decorated hero of the crossing of Danube at Zimnitza in 1877. Dragomirov had favored training officers for offensive warfare, promoted the elite guards regiments, and emphasizing the old Suvorov-era concept of the importance of soldier élan over military technology. Genrikh Leer, the old teacher of strategy at the Academy, was another tactical arch-conservative. As a firm supporter of Jominian principles, he trained the Russian officers to always look for firm and immutable solutions. He was also a representative of the "Western" strategic lobby,a group of generals for whom the menace of Germany had became an unchallenged strategic orthodoxy after 1870. With his military career focused on earlier Asiatic campaigns, Kuropatkin and his tashkentsy officers allies were willing to challenge this German-oriented strategic school as overtly dogmatic way of approaching the strategic needs of Russian Empire.

As a General Staff-trained officer who had planned Russian mobilization schemes for decades, Kuropatkin was painfully aware of the German threat. But he concluded that in order to win a possible confrontation against the Triple Alliance, Russia needed to fully mobilize her armies first. And while doing so she'd have to both initially prepare for defensive warfare, and to invest considerably more funds to modern weapons and communication technology. This conflict between two doctrinal schools contributed to situation where the old Academy generals with their persistent conservatism and unwillingness to confront the demands of modern warfare clung stubbornly to antiquated theories that were based on Napoleonic-era notions of military leadership. Ultimately Kuropatkin dealt with the Academy be the same method he had used with the Main Staff: unable to defeat it by using enough court intrigue to gain the favor of Nicholas II, he opted to bypass it by promoting officer training methods and opening new officer schools that marginalized the role of the Nicholas Academy.

Talented individuals had well-based ideas on how to improve the Army, but their ambitions foundered on the structures, practices and ideology of autocracy and noble privilege. Like the professionals in civilian society, the military officers did not have the autonomy to determine and enforce their own standards. the Czar and the aristocrats of the elite Guards corps all meddled in military affairs with little appreciation of the revolutionary transformation that warfare had undergone since the days of Borodino. The same Czar and his entourage that would not tolerate any autonomy for civil society or self-government in the civilian sphere could hardly be expected to allow the military to manage its affairs. Kuropatkin thus had to walk a tight rope between the whims of the Czar and his entourage, and his view of the necessity of further reforms. His policy of isolating the conservatives from the officer training led to a decision to grant the Military Districts much more leeway. This policy gave reform-minded high-ranking officers like Dmitrii Shcherbachev, Nikolai Golovin, Iurii Danilov, V.I. Gurko, von Korf and A.S. Lukomskii more room to train officers and troops without interference and to pursue their reform agendas relatively undisturbed.

Golovin’s vision, in particular, reflected the way the growing contacts between their French allies were exposing Russian military leaders to new ideas. His familiarity with the French military educational model had turned Golovin into an advocate for more investment in advanced weapons technology and communications systems. After attending to the French Ecole Superieure du Guerre, Golovin had declared himself as a proud disciple of Foch and his method of “applied tactics”, and had since gathered around him a party of young talented officers who sought to propagate new military doctrines to those of the epigones of the era of Leer and Dragomirov. They had an important following among the younger genshtabisty officers, who introduced new tactical doctrines in their areas of command and thereby considerably improved the training of recruits.

The tug-of-war between the conservatives and reformers in the Russian military led to a compromise of sorts. Czar Nicholas II was always greatly agitated to learn about doctrinal disputes, and stated that officers should discuss tactics, as matters of strategy were exclusively His domain to decide. Yet Nicholas II never really dared to challenge the Grand Duke Nicholas directly, and under his protection War Minister Kuropatkin could in turn protect his clients from anti-reformist interference, and allow them to focus on developing experimental troop training schemes that Kuropatkin then sought to utilize when compiling new GUGSh training manuals for general usage.

To the Russian military reformers protected by Kuropatkin and Grand Duke and opposed by the old generals, the traditional Russian officer training concepts of upravlenie (control) and pochin (initiative) did no longer represent the old stereotype of a brave officer shouting “Hurrah!” and leading the troops into charge. Instead they claimed that these military virtues should now be seen as the methodical application of professional military skills to ensure the persistent development of the battle in the necessary direction. On an operational level Kuropatkin and his proteges were planning the Army to short and decisive war, where the solution would be achieved by operational-level maneuver in the field. Meeting engagement was nearly ignored in the training manuals, but once forces were firmly in contact direct frontal confrontation was the preferable tactical approach. In infantry training this meant that as a standard practice the attacking force would fire one rifle volley, and then conduct a charge with fixed bayonets.

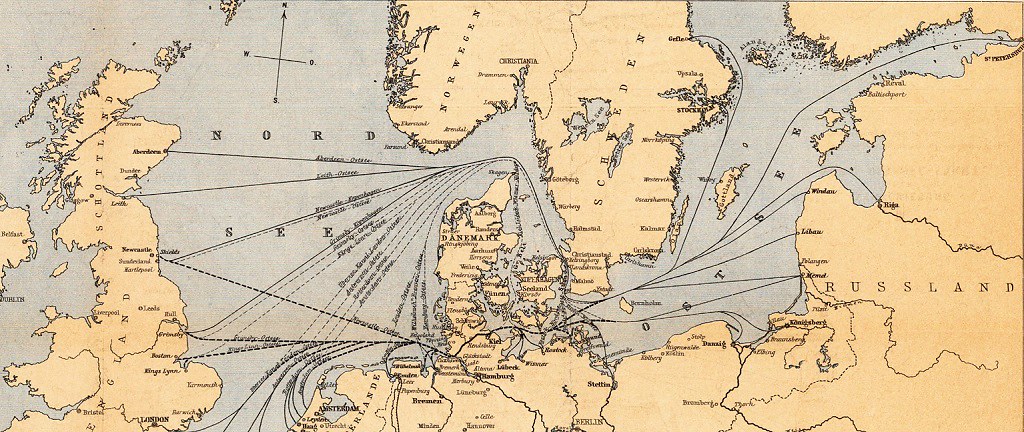

Kuropatkin did not concern himself with tactics - he focused on matters of logistics and strategy. To him the earlier campaigns in Central Asia and the Boxer War seemed to prove his earlier views that tactics were of secondary significance compared to the problems of food supply, sanitation, and hygiene of troops. For him, the primary cause of concern was the fact that first-line maneuver units that would initialize combat operations against the enemy were to be tethered to their own organic support units, which meant that logistics would become problematic at any time the distance between supporting rail-head and these formations would exceed two days’ field march. Because of this Kuropatkin warmly supported the idea that the supply infrastructure at the key borders of Russia should be expanded, so that the massive field armies of the Empire would be able to operate effectively during a four-to-six months long campaign in all possible theaters of operations.

1: In OTL the lectures were entirely censored.

The Resistance of the Old Guard

War Minister Kuropatkin felt from day one in his new job, that his duty was to finish the job his great role model had started decades earlier. For Kuropatkin it was clear that his paragon, the great Miliutin had correctly understood the key to the survival and greatness of Russian Empire: an educated, competent officer corps. The reform efforts started by Miliutin had thus focused on providing leadership for the army based on merit; from the start to the end of his tenure he had fought the strong aristocratic privileges that allowed incompetent officers to rise to high positions. This conflict, between merit and noble privilege, was still a key issue in Russian officer training when Kuropatkin took office. Kuropatkin greatly admired Miliutin, and inspired by his predecessors example he pushed further reforms in officer education with considerable political and administrative effectiveness. But whereas the great Miliutin had had the backing of the reforming tsar Alexander II, Kuropatkin had to deal with Nicholas II, who dogmatically defended the privileges of the aristocracy, the old generals and the “parade culture” that characterized the imperial army in general.

The battle over the inclusion of lectures about the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 into the curriculum of the General Staff Academy is a good example of the kind of systemic resistance the reforms promoted by Kuropatkin and his patron Grand Duke Nicholas faced. The Russo-Turkish War was the most recent war where Russia had fought, and the first one to be fought by the army since the reforms stared by Miliutin. Russian military-scientific interest towards the war had been considerable since it's conclusion, and both Kuropatkin and Grand Duke Nicholas had published books about the subject. So when Coloniel E.I. Martynov announced his intent to organize a series of lectures based on the work of a military-history commission that had been working on the war’s history for twenty years without publishing any findings before this, the higher ranks of the Russian officer corps naturally expressed a great deal of initial interest. The initial curiosity was met by a shock, when it became clear that Martynov would not hesitate to point out that the meddling of the Grand Dukes in decision-making had been behind several of the key operational failures in the war. Because members of the Imperial family still dominated the high command of the Russian army in 1877-78, such lectures, no matter how close to the truth, were political dynamite, and initially it seemed clear they could not and would not be tolerated at the Nicholas Academy. But after Kuropatkin consulted Martynov and pressured him to drop the criticism to Grand Duke Nicholas, the controversial lecture courses were eventually started in 1907, and turned into an annual course of the history of the war in the following year. Finally Russian officers could learn from their latest military encounter, instead relying on histories of European conflicts and the US Civil War.[1]

These kind of obstacles to Kuropatkin’s plans came from the legacy of officer education system inherited from General Mikhail Dragomirov, who had had both Academy teaching experience and a formidable field service as the commander of the important Kiev Military District and as the decorated hero of the crossing of Danube at Zimnitza in 1877. Dragomirov had favored training officers for offensive warfare, promoted the elite guards regiments, and emphasizing the old Suvorov-era concept of the importance of soldier élan over military technology. Genrikh Leer, the old teacher of strategy at the Academy, was another tactical arch-conservative. As a firm supporter of Jominian principles, he trained the Russian officers to always look for firm and immutable solutions. He was also a representative of the "Western" strategic lobby,a group of generals for whom the menace of Germany had became an unchallenged strategic orthodoxy after 1870. With his military career focused on earlier Asiatic campaigns, Kuropatkin and his tashkentsy officers allies were willing to challenge this German-oriented strategic school as overtly dogmatic way of approaching the strategic needs of Russian Empire.

As a General Staff-trained officer who had planned Russian mobilization schemes for decades, Kuropatkin was painfully aware of the German threat. But he concluded that in order to win a possible confrontation against the Triple Alliance, Russia needed to fully mobilize her armies first. And while doing so she'd have to both initially prepare for defensive warfare, and to invest considerably more funds to modern weapons and communication technology. This conflict between two doctrinal schools contributed to situation where the old Academy generals with their persistent conservatism and unwillingness to confront the demands of modern warfare clung stubbornly to antiquated theories that were based on Napoleonic-era notions of military leadership. Ultimately Kuropatkin dealt with the Academy be the same method he had used with the Main Staff: unable to defeat it by using enough court intrigue to gain the favor of Nicholas II, he opted to bypass it by promoting officer training methods and opening new officer schools that marginalized the role of the Nicholas Academy.

Talented individuals had well-based ideas on how to improve the Army, but their ambitions foundered on the structures, practices and ideology of autocracy and noble privilege. Like the professionals in civilian society, the military officers did not have the autonomy to determine and enforce their own standards. the Czar and the aristocrats of the elite Guards corps all meddled in military affairs with little appreciation of the revolutionary transformation that warfare had undergone since the days of Borodino. The same Czar and his entourage that would not tolerate any autonomy for civil society or self-government in the civilian sphere could hardly be expected to allow the military to manage its affairs. Kuropatkin thus had to walk a tight rope between the whims of the Czar and his entourage, and his view of the necessity of further reforms. His policy of isolating the conservatives from the officer training led to a decision to grant the Military Districts much more leeway. This policy gave reform-minded high-ranking officers like Dmitrii Shcherbachev, Nikolai Golovin, Iurii Danilov, V.I. Gurko, von Korf and A.S. Lukomskii more room to train officers and troops without interference and to pursue their reform agendas relatively undisturbed.

Golovin’s vision, in particular, reflected the way the growing contacts between their French allies were exposing Russian military leaders to new ideas. His familiarity with the French military educational model had turned Golovin into an advocate for more investment in advanced weapons technology and communications systems. After attending to the French Ecole Superieure du Guerre, Golovin had declared himself as a proud disciple of Foch and his method of “applied tactics”, and had since gathered around him a party of young talented officers who sought to propagate new military doctrines to those of the epigones of the era of Leer and Dragomirov. They had an important following among the younger genshtabisty officers, who introduced new tactical doctrines in their areas of command and thereby considerably improved the training of recruits.

The tug-of-war between the conservatives and reformers in the Russian military led to a compromise of sorts. Czar Nicholas II was always greatly agitated to learn about doctrinal disputes, and stated that officers should discuss tactics, as matters of strategy were exclusively His domain to decide. Yet Nicholas II never really dared to challenge the Grand Duke Nicholas directly, and under his protection War Minister Kuropatkin could in turn protect his clients from anti-reformist interference, and allow them to focus on developing experimental troop training schemes that Kuropatkin then sought to utilize when compiling new GUGSh training manuals for general usage.

To the Russian military reformers protected by Kuropatkin and Grand Duke and opposed by the old generals, the traditional Russian officer training concepts of upravlenie (control) and pochin (initiative) did no longer represent the old stereotype of a brave officer shouting “Hurrah!” and leading the troops into charge. Instead they claimed that these military virtues should now be seen as the methodical application of professional military skills to ensure the persistent development of the battle in the necessary direction. On an operational level Kuropatkin and his proteges were planning the Army to short and decisive war, where the solution would be achieved by operational-level maneuver in the field. Meeting engagement was nearly ignored in the training manuals, but once forces were firmly in contact direct frontal confrontation was the preferable tactical approach. In infantry training this meant that as a standard practice the attacking force would fire one rifle volley, and then conduct a charge with fixed bayonets.

Kuropatkin did not concern himself with tactics - he focused on matters of logistics and strategy. To him the earlier campaigns in Central Asia and the Boxer War seemed to prove his earlier views that tactics were of secondary significance compared to the problems of food supply, sanitation, and hygiene of troops. For him, the primary cause of concern was the fact that first-line maneuver units that would initialize combat operations against the enemy were to be tethered to their own organic support units, which meant that logistics would become problematic at any time the distance between supporting rail-head and these formations would exceed two days’ field march. Because of this Kuropatkin warmly supported the idea that the supply infrastructure at the key borders of Russia should be expanded, so that the massive field armies of the Empire would be able to operate effectively during a four-to-six months long campaign in all possible theaters of operations.

1: In OTL the lectures were entirely censored.

Last edited: