Archibald

Banned

Flight Day 1

January 16, 2003, 10:39 EST

Cape Canaveral Launch Complex 39, Florida

That cold day of January Space Shuttle Columbia was to fly a Spacehab, a class of mission the International Space Station would made extinct soon.

The old orbiter would be reduced to Hubble servicing every four years, but even these missions were nearing their end. Columbia in fact had only mission planned in the 21th century: that of retrieving Hubble. Of bringing it back to Earth, somewhere in the next decade. As for Columbia three siblings, per lack of viable successor - the shuttle was so unique a design NASA had failed to replace it - a plan was seriously considered to extend the space shuttle lives to the year 2020.

The SSME lit first, and for seven seconds as they went full thrust they were thoroughly monitored.

Then the immense solid rocket motors awoke into life and for a fraction of second the shuttle tried to lift its launch pad through the huge power of its five engines. Big pins were blown explosively, freeing the space shuttle which literally jumped upwards, throwing flames in the direction of orbit.

Only ten minutes later and after an apparently nominal ascent the tank was discarded, the engines shut down, and Columbia peacefully drifted into orbit.

What was to be a boring, last-of-its-kind, long delayed Spacehab mission had begun.

The crew were all professionals deeply committed to their mission whatever the rest of the world, or NASA astronaut corp, could think about it. Half of the crew were rookies; and they come for all walk of life. Kalpana Chawla was born in India; guest cosmonaut Ilan Ramon was an Israeli pilot ; Michael Anderson was an afro-american and a veteran of the last flight to Mir four years before. Commander Rick Husband was a veteran of another Columbia / Spacehab mission years before. All others - William McCool, Laurel Clark and David Brown - were living the thrill of their first foray into orbit.

...

NASA space shuttle had spent his whole career chasing elusive space stations. It was by itself the original sinner, since it had killed the space station it was to go in the very first place.

In 1970, after losing nuclear shuttles to the Moon and Mars

NASA pinned all hopes into a balanced package - the winged shuttle would fly to a space station. Even that package, however, was impossible to fund, and soon a choice had to be made - station or shuttle ?

The reasoning at the time was the shuttle would be the truck to build the station, so the truck had to come first, and the station was pushed by a decade. The soviets, for their part, picked up the opposite path - station first, shuttle... someday. In the end Buran only fly once.

Because it had no destinations to go - no Moon, no Mars, not even a space station - the shuttle had to seek an interim job to fill its first decade of existence. It ultimately earned a life launching satellites, all of them - military, science, and commercial satellites. By a bizarre twist of fate a federal agency like NASA found itself competing with private companies, notably Arianespace.

In 1973 the shuttle was given all American satellites on a silver plate but the price to pay was that it was to earn money, and to achieve that it had to fly no less than 60 times a year - once a week ! Unfortunately experience would prove the vehicle could fly at best 8 times a year (in 1996).

Early in the 80's NASA only partially acknowledged that reality by cutting the shuttle "ideal" flight rate to 24 a year, still three times more than what the shuttle could endure.

From 1984 onwards the space agency had its back against a wall - 24 flights a year or lose face against Congress and the World.

In 1985 the shuttle flew 10 times with two more flights cancelled. Still half the nominal target, yet the agency was already on its heels, scrapping everything it had for money and personal.

In 1986 it was to fly 16 times, but as of mid-January repeated delays with the last 1985 flight had already ruined the schedule. Not only was the flight schedule gruelling, it was also constrained by fixed planetary launch windows - the Halley comet and planet Jupiter would not suffer any delay. The robotic probes would not wait !

Since December shuttle flights had been pretty nightmarish. Columbia early December mission had lifted off early January; and from then things got worse. Delays on January 22; technical glitches on January 24 and January 27; and, last but not least, bad weather forecast all plotted to ruin the schedule. Enough was enough, for the aforementioned reasons the shuttle had to fly. After a handful of stormy, controversial video conferences in the evening of January 27 the decision was made to launch on a day that had not only the coldest temperatures on the ground, but also very brutal jet streams at 30 000 ft.

That Tuesday, January 28 1986 the weather was definitively discouraging. Yet for the sake of impossible flight rates determining NASA credibility and unforgiving planetary launch windows, Space Shuttle Challenger was bound to go through these disastrous weather conditions.

It did not made it.

The night before the launch icy temperatures froze a join on a booster, the jet stream shook the frozen join; a tongue of flame then leaked from the damaged booster onto the external tank, piercing it. The tank violently disintegrated ... and the crewed orbiter above it was blown to pieces. The crew cabin retained a relative integrity but crashed into the ocean, killing all seven crew members including a school teacher that was to give a lesson from space. A major public relation hit for NASA now had very horribly and tragically backfired. Under Presidential inquiry the shuttle fleet was grounded for two and half years.

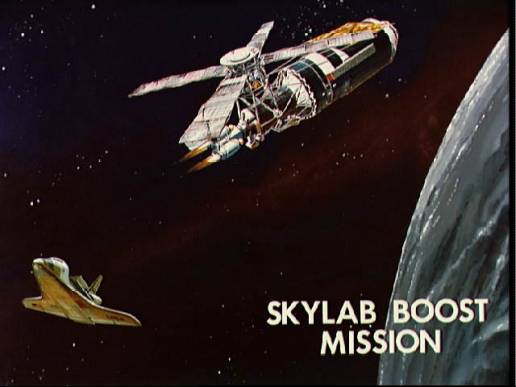

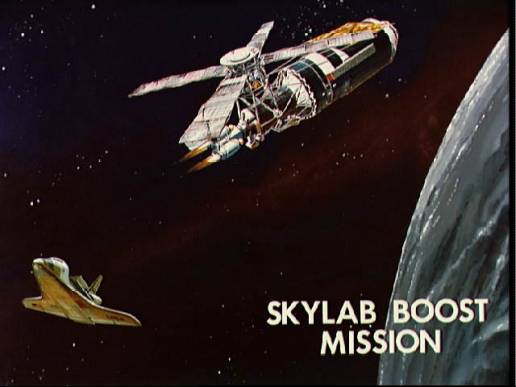

Meanwhile the space station case was no better. The shuttle kept missing rendezvous with possible orbital outposts. Old Skylab could no wait for the shuttle to overcome its delays, and burned into the atmosphere in 1979.

Afghanistan, Poland and Reagan election ensured no shuttle ever docked to a Soviet Salyut operated between 1978 and 1985. Salyut was improved into Mir and that time the shuttle was present to the rendezvous. After 1995 and for three years the shuttle meet the now Russian space station. It was a wonderful piece of international cooperation.

What still missed, however, was some big American space station, a return of the project postponed by a decade to build the shuttle. In 1984 Reagan did just that, giving NASA $8 billion to build the station of their dreams.

What none foresee at the time was it would be fourteen years before the first module was launched, and that module was a Russian one of Mir heritage !

At the turn of the century NASA at least was building its (international) space station; the shuttle had returned to its original job as imagined in 1969. It had taken the best part of three decades to reach that nirvana. The shuttle credibility, however, had been definitively ruined by the disastrous satellite business leading to the Challenger disaster.

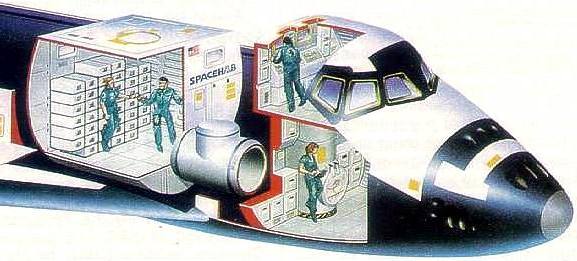

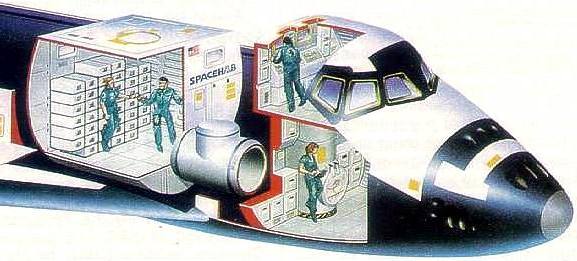

As the shuttle missed a space station badly, and because that satellite job was not truly satisfying, early in the 70's an inexpensive ersatz of space station had been imagined. Europe Spacelab (and later its private incarnation Spacehab space shuttle Columbia carried that January 16, 2003) were space station without wings. They would fly into orbit within the shuttle payload bay but, in order to save money they would draw their life from the shuttle itself, meaning they could not be released to live a space station life. Instead they would stuck aboard the shuttle and get down with it at the end of the mission. Bluntly, Spacelab flew for brief 15 days missions instead of Mir continuous 15 years. The ISS, of course, would change that; but it had been delayed again and again and again.

Circa 1997 and waiting for the never-coming ISS, Congress encouraged NASA flying Spacehab in a couple of missions. The space agency, however, did not give a rat: energy and money instead flowed into the ISS. The shore mission was delayed by two full years and ultimately fell on the oldest of the shuttle, veteran Columbia.

It had once been the member of a troika that included the now defunct Challenger and the mostly forgotten Enterprise. The last two, unlike Columbia, were mock-ups; and one of the two mock-up was to be turned into a fully fledged shuttle to fly along Columbia itself. Early on the honour belonged to Enterprise; but Challenger was found to be easier to modify, and Enterprise never flew into orbit. With Challenger dead and Enterprise stuck in a museum old Columbia found itself isolated; it become a relic the other three shuttles - Discovery, Atlantis and Challenger successor Endeavour - looked with disdain.

Columbia was considered a relic in the sense that, build ten years before Discovery its structure was somewhat heavier and its payload was lower. It happened the ISS was in a Russian-friendly orbit, and that orbit induced severe penalties for all shuttles - but Columbia higher mass made the penalties even more cumbersome.

In 1996 NASA decided old Columbia would not build the ISS; it instead entered into a semi-retirement, doing every single non-ISS missions, although there were not many of them. As a result Columbia became intimate with the Hubble space telescope... and Spacehab.

January 16, 2003, 10:39 EST

Cape Canaveral Launch Complex 39, Florida

That cold day of January Space Shuttle Columbia was to fly a Spacehab, a class of mission the International Space Station would made extinct soon.

The old orbiter would be reduced to Hubble servicing every four years, but even these missions were nearing their end. Columbia in fact had only mission planned in the 21th century: that of retrieving Hubble. Of bringing it back to Earth, somewhere in the next decade. As for Columbia three siblings, per lack of viable successor - the shuttle was so unique a design NASA had failed to replace it - a plan was seriously considered to extend the space shuttle lives to the year 2020.

The SSME lit first, and for seven seconds as they went full thrust they were thoroughly monitored.

Then the immense solid rocket motors awoke into life and for a fraction of second the shuttle tried to lift its launch pad through the huge power of its five engines. Big pins were blown explosively, freeing the space shuttle which literally jumped upwards, throwing flames in the direction of orbit.

Only ten minutes later and after an apparently nominal ascent the tank was discarded, the engines shut down, and Columbia peacefully drifted into orbit.

What was to be a boring, last-of-its-kind, long delayed Spacehab mission had begun.

The crew were all professionals deeply committed to their mission whatever the rest of the world, or NASA astronaut corp, could think about it. Half of the crew were rookies; and they come for all walk of life. Kalpana Chawla was born in India; guest cosmonaut Ilan Ramon was an Israeli pilot ; Michael Anderson was an afro-american and a veteran of the last flight to Mir four years before. Commander Rick Husband was a veteran of another Columbia / Spacehab mission years before. All others - William McCool, Laurel Clark and David Brown - were living the thrill of their first foray into orbit.

...

NASA space shuttle had spent his whole career chasing elusive space stations. It was by itself the original sinner, since it had killed the space station it was to go in the very first place.

In 1970, after losing nuclear shuttles to the Moon and Mars

NASA pinned all hopes into a balanced package - the winged shuttle would fly to a space station. Even that package, however, was impossible to fund, and soon a choice had to be made - station or shuttle ?

The reasoning at the time was the shuttle would be the truck to build the station, so the truck had to come first, and the station was pushed by a decade. The soviets, for their part, picked up the opposite path - station first, shuttle... someday. In the end Buran only fly once.

Because it had no destinations to go - no Moon, no Mars, not even a space station - the shuttle had to seek an interim job to fill its first decade of existence. It ultimately earned a life launching satellites, all of them - military, science, and commercial satellites. By a bizarre twist of fate a federal agency like NASA found itself competing with private companies, notably Arianespace.

In 1973 the shuttle was given all American satellites on a silver plate but the price to pay was that it was to earn money, and to achieve that it had to fly no less than 60 times a year - once a week ! Unfortunately experience would prove the vehicle could fly at best 8 times a year (in 1996).

Early in the 80's NASA only partially acknowledged that reality by cutting the shuttle "ideal" flight rate to 24 a year, still three times more than what the shuttle could endure.

From 1984 onwards the space agency had its back against a wall - 24 flights a year or lose face against Congress and the World.

In 1985 the shuttle flew 10 times with two more flights cancelled. Still half the nominal target, yet the agency was already on its heels, scrapping everything it had for money and personal.

In 1986 it was to fly 16 times, but as of mid-January repeated delays with the last 1985 flight had already ruined the schedule. Not only was the flight schedule gruelling, it was also constrained by fixed planetary launch windows - the Halley comet and planet Jupiter would not suffer any delay. The robotic probes would not wait !

Since December shuttle flights had been pretty nightmarish. Columbia early December mission had lifted off early January; and from then things got worse. Delays on January 22; technical glitches on January 24 and January 27; and, last but not least, bad weather forecast all plotted to ruin the schedule. Enough was enough, for the aforementioned reasons the shuttle had to fly. After a handful of stormy, controversial video conferences in the evening of January 27 the decision was made to launch on a day that had not only the coldest temperatures on the ground, but also very brutal jet streams at 30 000 ft.

That Tuesday, January 28 1986 the weather was definitively discouraging. Yet for the sake of impossible flight rates determining NASA credibility and unforgiving planetary launch windows, Space Shuttle Challenger was bound to go through these disastrous weather conditions.

It did not made it.

The night before the launch icy temperatures froze a join on a booster, the jet stream shook the frozen join; a tongue of flame then leaked from the damaged booster onto the external tank, piercing it. The tank violently disintegrated ... and the crewed orbiter above it was blown to pieces. The crew cabin retained a relative integrity but crashed into the ocean, killing all seven crew members including a school teacher that was to give a lesson from space. A major public relation hit for NASA now had very horribly and tragically backfired. Under Presidential inquiry the shuttle fleet was grounded for two and half years.

Meanwhile the space station case was no better. The shuttle kept missing rendezvous with possible orbital outposts. Old Skylab could no wait for the shuttle to overcome its delays, and burned into the atmosphere in 1979.

Afghanistan, Poland and Reagan election ensured no shuttle ever docked to a Soviet Salyut operated between 1978 and 1985. Salyut was improved into Mir and that time the shuttle was present to the rendezvous. After 1995 and for three years the shuttle meet the now Russian space station. It was a wonderful piece of international cooperation.

What still missed, however, was some big American space station, a return of the project postponed by a decade to build the shuttle. In 1984 Reagan did just that, giving NASA $8 billion to build the station of their dreams.

What none foresee at the time was it would be fourteen years before the first module was launched, and that module was a Russian one of Mir heritage !

At the turn of the century NASA at least was building its (international) space station; the shuttle had returned to its original job as imagined in 1969. It had taken the best part of three decades to reach that nirvana. The shuttle credibility, however, had been definitively ruined by the disastrous satellite business leading to the Challenger disaster.

As the shuttle missed a space station badly, and because that satellite job was not truly satisfying, early in the 70's an inexpensive ersatz of space station had been imagined. Europe Spacelab (and later its private incarnation Spacehab space shuttle Columbia carried that January 16, 2003) were space station without wings. They would fly into orbit within the shuttle payload bay but, in order to save money they would draw their life from the shuttle itself, meaning they could not be released to live a space station life. Instead they would stuck aboard the shuttle and get down with it at the end of the mission. Bluntly, Spacelab flew for brief 15 days missions instead of Mir continuous 15 years. The ISS, of course, would change that; but it had been delayed again and again and again.

Circa 1997 and waiting for the never-coming ISS, Congress encouraged NASA flying Spacehab in a couple of missions. The space agency, however, did not give a rat: energy and money instead flowed into the ISS. The shore mission was delayed by two full years and ultimately fell on the oldest of the shuttle, veteran Columbia.

It had once been the member of a troika that included the now defunct Challenger and the mostly forgotten Enterprise. The last two, unlike Columbia, were mock-ups; and one of the two mock-up was to be turned into a fully fledged shuttle to fly along Columbia itself. Early on the honour belonged to Enterprise; but Challenger was found to be easier to modify, and Enterprise never flew into orbit. With Challenger dead and Enterprise stuck in a museum old Columbia found itself isolated; it become a relic the other three shuttles - Discovery, Atlantis and Challenger successor Endeavour - looked with disdain.

Columbia was considered a relic in the sense that, build ten years before Discovery its structure was somewhat heavier and its payload was lower. It happened the ISS was in a Russian-friendly orbit, and that orbit induced severe penalties for all shuttles - but Columbia higher mass made the penalties even more cumbersome.

In 1996 NASA decided old Columbia would not build the ISS; it instead entered into a semi-retirement, doing every single non-ISS missions, although there were not many of them. As a result Columbia became intimate with the Hubble space telescope... and Spacehab.

Last edited: