Story of a Party - Chapter XVII

Now is the Summer of our Discontent

"The constitution regulates our stewardship; the constitution devotes the domain to union, to justice, to defense, to welfare and to liberty. But there is a higher law than the Constitution, which regulates our authority over the domain, and devotes it to the same noble purposes."

- William Henry Seward

***

Broad Street, Charleston, South Carolina in 1863.

From "Deconstruction and Reconstruction: A History of the Postbellum United States, 1862-1924" by Walker Smith

Abrams Publishing, Philadelphia, 1956

"The acquisitions of Sonora, Alaska and British Columbia, despite Seward's hopes, served little to unite the nation behind his expansionist agenda; as such, after his first year in office, he increasingly turned to face the massive internal problems of the nation. The occupied South was, of course, still a running sore, and one which did not seem to run dry. Various Establisher groups were waging guerrilla wars against the army of occupation, supported by those remaining ex-Confederates who had not been stripped of their land and rights. Those plantations that were run by freedmen were particularly frequently targeted, and free blacks were lynched by the dozens across the South…"

***

Outside Lowndesboro, Alabama

United States

June 21, 1866

Summers in the Deep South were always hot, but this one was scorching, with temperatures in the high nineties at best [1]. Jake, who'd grown up in the significantly cooler Missouri, was sweating quite a bit, and constantly had to wipe his forehead with a handkerchief to keep the sweat from getting in his eyes. He was waiting for a group of other men from around the state, who were joining him to discuss the situation and any opportunities they might have to change it.

"Jake Sullivan," a drawling voice called out from behind him. "I haven't seen you since… well, before the war."

Jake turned around. Facing him were Smiley Johnston, an old friend of his that he'd met while working on a plantation in eastern Texas, and several others. He recognised George Thomas, the old planter at Meadowlawn before the rebellion, and Jim Thomson, another overseer in the county. There were several people who looked like they came from the North, actually; paler than most in normal weather, their skin now resembled smoked ham in its colour.

"Are all of us here?" he asked.

"As far as I can tell," said Thomas, "only old Dixie is missing." Some people chuckled at the man's pun, but overall, the party remained silent. Thomas spoke on.

"The situation here is getting unacceptable," he said. "The upstart niggers, aided by those damn Yankee carpetbaggers, are threatening to overthrow the natural order of things. The white man was created in God's image to rule over the lesser races, and now those very races have seen it fit to overthrow their natural masters and get the foolish notion that they are equal to the white man! The carpetbaggers and all who follow their misguided ideals are traitors to their race. We need to return the South and, in time, also the North, to the ways of the old time, the time before the war!" Thomas' face was nearly red. "We need the old order back! Say it with me: we need the old order back!"

***

From "Deconstruction and Reconstruction: A History of the Postbellum United States, 1862-1924" by Walker Smith

Abrams Publishing, Philadelphia, 1956

"As with the slave rebellions during the Civil War, the all-out race war between the Establishers and the freedmen began in the Black Belt of Alabama, in the summer of 1866. The army of occupation took to more violent measures against both groups, but mostly against the Establishers, leading to the Establishers vilifying the "Yankee carpetbaggers" as "traitors to their race" and "not really proper white men", which fuelled their cause across the South, as their claims were seen as more justified. The fighting soon spread in all directions; the two regions that became particularly infamous, apart from the Alabama Black Belt, were the Low Country in South Carolina, and the Gulf Coast between roughly New Orleans and Tallahassee. For this reason, Seward split off the Military District of West Florida from parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida, the latter being renamed as East Florida. The new territory was to be occupied by a new army corps, made up largely of New Yorker and Pennsylvanian volunteers. Few people actually volunteered for service, knowing that they would be guarding their own countrymen from each other, and Seward briefly considered enacting the first peacetime draft in U.S. history. However, the measure was never put to the vote due to its unconstitutional nature, which may be the only saving grace of the Seward Administration's internal policy. Instead, he formed a new corps from parts of old ones, chiefly those stationed in the districts in whose territories the new district had been erected. This led to overextension, since those states (possibly excepting East Florida) were the ones where the fighting was the most intense.

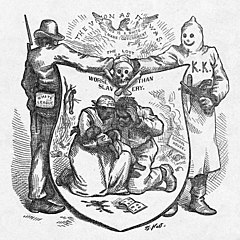

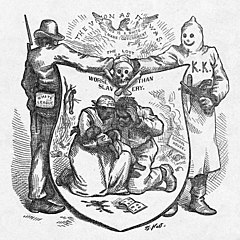

Political cartoon from Harper's Weekly, decrying the Establisher goals as "worse than Slavery".

By the summer of 1866, the army of occupation was forced to use more and more harsh methods of policing the South, and Seward's popularity was rapidly declining. Many moderate Republicans, disgusted with Seward's policies toward Reconstruction (which they dubbed "Deconstruction") left the party and joined the Constitutional Union, for which they ran in the midterms; as a result, the Republicans lost their supermajorities in both houses, although retaining simple majorities in both. However, Seward still retained strong support among the radical Republicans, who believed that the Establishers were a danger to equality and the freedmen's freedom.

The Readmission Bill, in large part penned by Thaddeus Stevens, was put before Congress on May 18, 1867. It stipulated that all known ex-Confederates and half of the entire populations of all Southern states that wanted to rejoin the Union had to take the Ironclad Oath, by which they promised to never rebel against government authority again. The states also had to have "quelled all such military and paramilitary activity within its borders whose goals involve the active opposition to government authority". This bill was controversial, but was still passed and signed into law due to the radicals' control of the Republican Party and the Republicans' control of Congress. The only state readmitted by this act was Missouri, which had only very narrowly joined the Confederacy to begin with, and had significant Unionist sentiments within its borders even with the loss of Osage. Missouri was readmitted on April 4, 1868.

By the end of 1867, the situation in the South was almost beyond hope. The army of occupation had suffered debilitating casualties in fending off Establisher attacks, and many areas were seeing their local garrisons withdrawn, leading to spikes of violence in those areas. The army was forced to concentrate itself on major cities, and much of the countryside was overrun with Establisher guerrillas. Many a courier was sent out never to return, and the standard practice adopted after a while was to send as many as six couriers with the same message in order for any information to get around. The violence between races was also intensifying, with some weeks seeing as many as twenty lynchings in a single state. The Establishers never even attempted to hide their racism and their unwavering opposition against giving the blacks any more rights whatsoever than they had before the Civil War. This fact, almost alone, was what kept Seward in office over the vociferous protests of nearly everyone but the radicals. By March of 1868, the administration was contemplating allowing the use of more malicious counterinsurgency tactics such as the salting of farmland and destruction of telegraph lines. At this crucial time, an election was held, which put the fate of the occupied South in the hands of the voters…"

***

From "A History of America through its Presidents"

John Bachmann & Son, Bluefields, Nicaragua, 1945

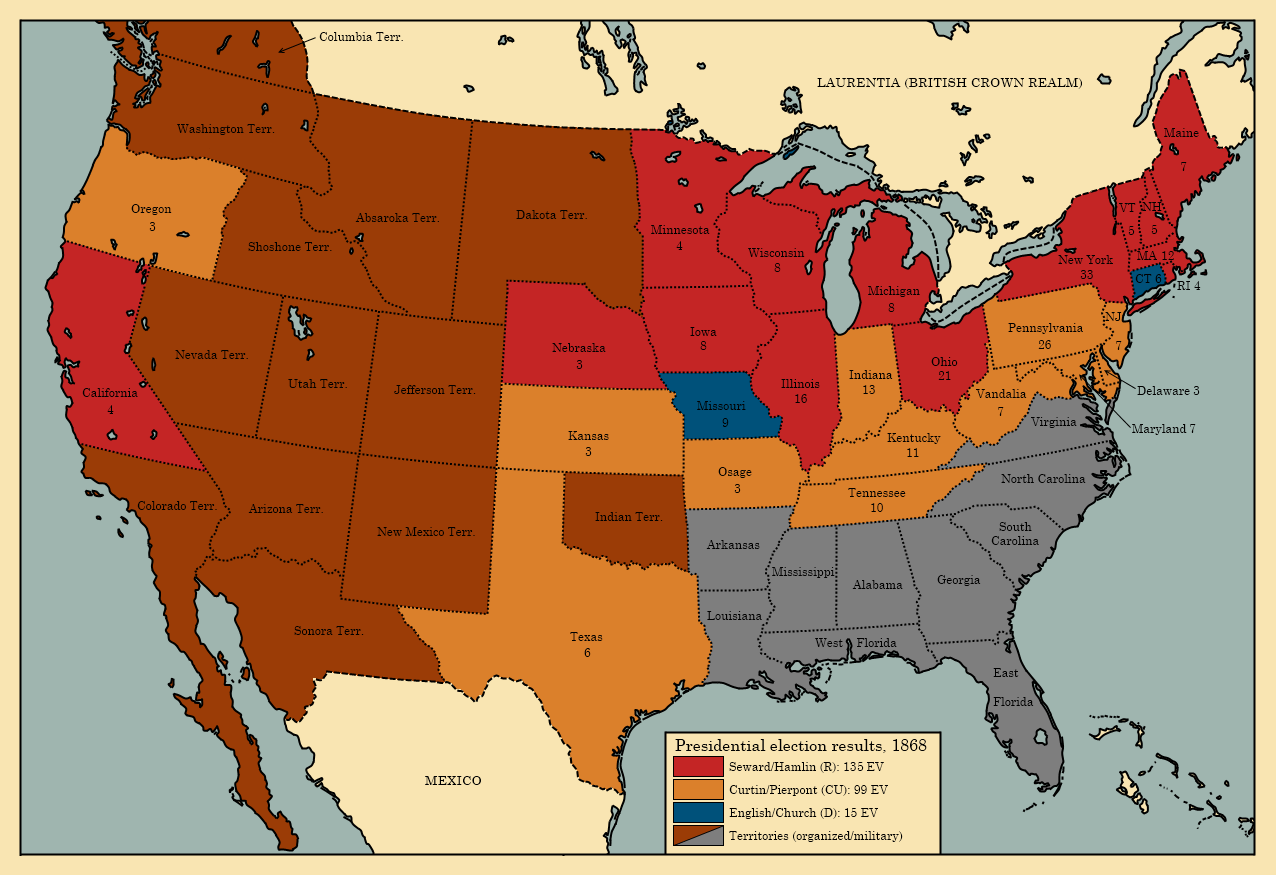

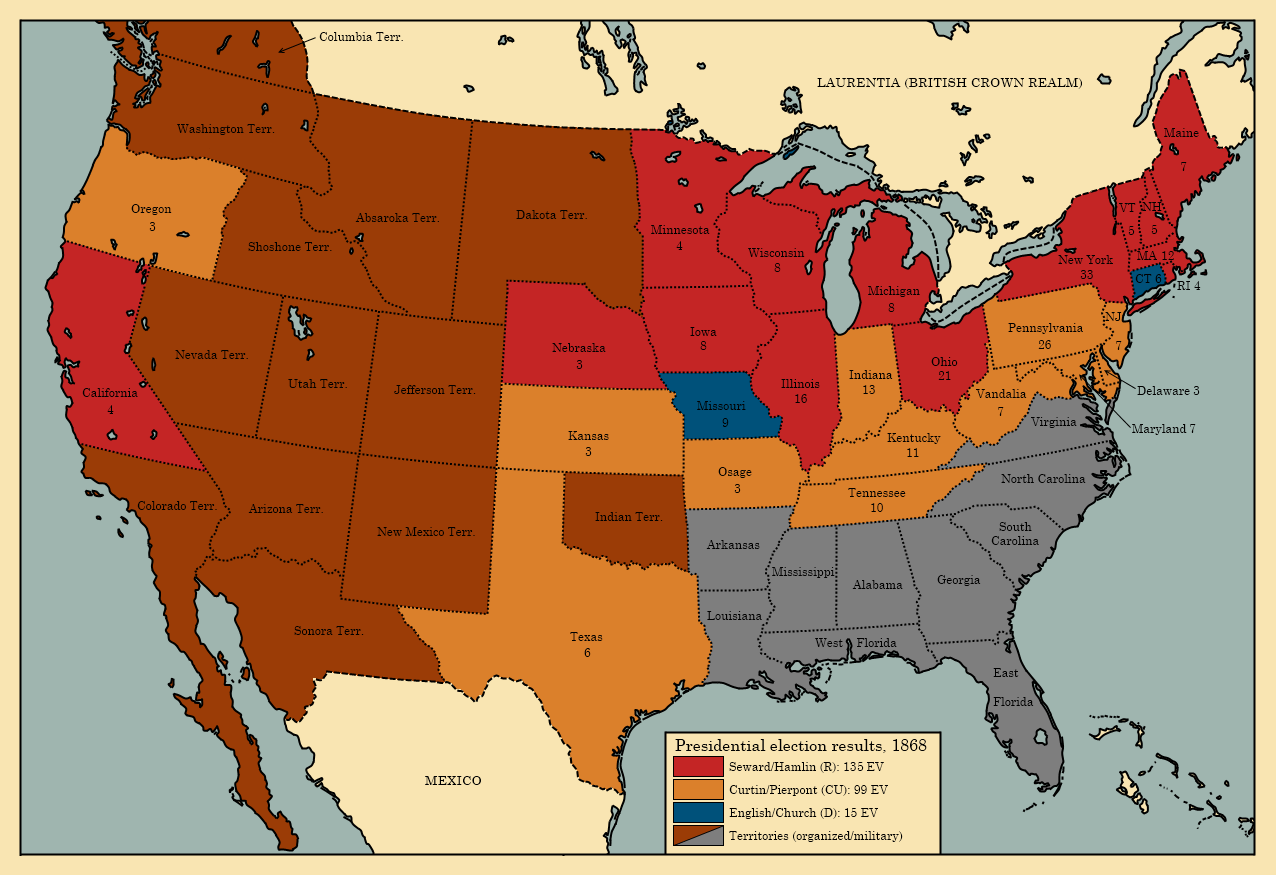

"1868 presidential election

The election of 1868 was a hard-fought battle between the Republicans and the Constitutional Unionists, with the Democrats caught in the middle but chiefly supporting the Constitutional Unionists, over Seward's reckless policies toward the South. Many Southerners in the border states were enraged over the forcible selling of land to the freedmen, the army presence in the Confederate states to prevent segregation, the lack of compensation for the wartime burning of barns and crops, and a host of other issues. Even in the North, many people found that the road Seward pursued was much too hard on the South, and they wept over the destruction of the historic cities and landscapes of Virginia and Georgia, which little had been done to mend. However, there was also a prominent feeling that the South deserved punishment for initiating the war.

The Republican convention, held in Harrisburg on April 3, was a fairly quick affair. It was thought that avenging the war and creating a racially equal society came before fairly mending relations with the governments of the Southern states, and so Seward and Hamlin had no difficulty in getting re-nominated.

The Constitutional Union convention in Baltimore was another matter entirely. The delegates debated for three days over which candidates to put forth, with almost every state delegation having its own "favourite son" who they voted for. Eventually the debate settled down, and it was realised that someone from a large Northern state would be necessary to win the election, since mistrust of Southerners still ran too high for one to gain office. The convention eventually settled on the wartime Governor of Pennsylvania, Andrew Gregg Curtin, who had previously been a Republican, but had switched sides when Seward was elected and began imposing his own methods of reconstruction. For Vice President they nominated Francis Harrison Pierpont, the Governor of Vandalia, who was thought to be able to sway the Upper South.

Andrew Gregg Curtin, nominee of the Constitutional Union.

The Democrats had an equally hard time settling on candidates, but eventually decided on a dark horse, the Governor of Connecticut, James Edward English. For Vice President they selected Sanford Church, the former Lieutenant-Governor of New York. [2]

James E. English, Democratic nominee.

The campaigning was extremely harsh, an attribute which characterised many election campaigns of the era. The Constitutional Unionists and the Democrats attacked the Republicans for their harsh reconstruction policies, condemning Seward and his policies as "the Harrowing of the South", and blamed him personally for the civil and political strife that had plagued the South in the five years since war's end. In return, the Republicans condemned the Unionists and, especially, the Democrats as traitors and rebel sympathisers. Famously, the Hartford Post, which at the time was Republican-aligned, described English as "as much of a traitor as Tyler [3]". The Unionists and Democrats, however, were far from united in their efforts to oppose the Republicans, and quarrelled almost as much between one another, chiefly over economic policy, with the Unionists favouring protectionism to strengthen industry, and the Democrats continuing with their established free trade advocacy.

All three parties fared fairly well in the polls, with the Democrats lagging behind a bit, but still maintaining a good percentage of the popular vote. In the end, however, no candidate managed to gain the majority needed to win, Seward notoriously falling short by a single vote, and so, for the second time in United States history, the election was sent to the House of Representatives."

***

[1] Fahrenheit, of course. The US is still using it.

[2] So, why not Seymour? Well, IOTL he presided over the nominating convention, and repeatedly refused to accept, stating first that "I must not be nominated by this Convention, as I could not accept the nomination if tendered. My own inclination prompted me to decline at the outset; my honor compels me to do so now. It is impossible, consistently with my position, to allow my name to be mentioned in this Convention against my protest", and then (once several state delegations had announced that he was the only candidate they would accept) "I have no terms in which to tell of my regret that my name has been brought before this convention. God knows that my life and all that I value most in life I would give for the good of my country, which I believe to be identified with that of the Democratic party, but when I said that I could not be a candidate, I mean it! I could not receive the nomination without placing not only myself but the Democratic party in a false position. God bless you for your kindness to me, but your candidate I cannot be." When he had gone out to rest, the convention nominated him unanimously without him even knowing there was a ballot.

[3] IOTL, the Hartford Post wrote of Seymour as "as much of a corpse" as Buchanan, who had just died at the time. ITTL, with Buchanan losing, the quote instead recalls John Tyler, who died as a Confederate Congressman ITTL.

***

Now is the Summer of our Discontent

"The constitution regulates our stewardship; the constitution devotes the domain to union, to justice, to defense, to welfare and to liberty. But there is a higher law than the Constitution, which regulates our authority over the domain, and devotes it to the same noble purposes."

- William Henry Seward

***

Broad Street, Charleston, South Carolina in 1863.

From "Deconstruction and Reconstruction: A History of the Postbellum United States, 1862-1924" by Walker Smith

Abrams Publishing, Philadelphia, 1956

"The acquisitions of Sonora, Alaska and British Columbia, despite Seward's hopes, served little to unite the nation behind his expansionist agenda; as such, after his first year in office, he increasingly turned to face the massive internal problems of the nation. The occupied South was, of course, still a running sore, and one which did not seem to run dry. Various Establisher groups were waging guerrilla wars against the army of occupation, supported by those remaining ex-Confederates who had not been stripped of their land and rights. Those plantations that were run by freedmen were particularly frequently targeted, and free blacks were lynched by the dozens across the South…"

***

Outside Lowndesboro, Alabama

United States

June 21, 1866

Summers in the Deep South were always hot, but this one was scorching, with temperatures in the high nineties at best [1]. Jake, who'd grown up in the significantly cooler Missouri, was sweating quite a bit, and constantly had to wipe his forehead with a handkerchief to keep the sweat from getting in his eyes. He was waiting for a group of other men from around the state, who were joining him to discuss the situation and any opportunities they might have to change it.

"Jake Sullivan," a drawling voice called out from behind him. "I haven't seen you since… well, before the war."

Jake turned around. Facing him were Smiley Johnston, an old friend of his that he'd met while working on a plantation in eastern Texas, and several others. He recognised George Thomas, the old planter at Meadowlawn before the rebellion, and Jim Thomson, another overseer in the county. There were several people who looked like they came from the North, actually; paler than most in normal weather, their skin now resembled smoked ham in its colour.

"Are all of us here?" he asked.

"As far as I can tell," said Thomas, "only old Dixie is missing." Some people chuckled at the man's pun, but overall, the party remained silent. Thomas spoke on.

"The situation here is getting unacceptable," he said. "The upstart niggers, aided by those damn Yankee carpetbaggers, are threatening to overthrow the natural order of things. The white man was created in God's image to rule over the lesser races, and now those very races have seen it fit to overthrow their natural masters and get the foolish notion that they are equal to the white man! The carpetbaggers and all who follow their misguided ideals are traitors to their race. We need to return the South and, in time, also the North, to the ways of the old time, the time before the war!" Thomas' face was nearly red. "We need the old order back! Say it with me: we need the old order back!"

***

From "Deconstruction and Reconstruction: A History of the Postbellum United States, 1862-1924" by Walker Smith

Abrams Publishing, Philadelphia, 1956

"As with the slave rebellions during the Civil War, the all-out race war between the Establishers and the freedmen began in the Black Belt of Alabama, in the summer of 1866. The army of occupation took to more violent measures against both groups, but mostly against the Establishers, leading to the Establishers vilifying the "Yankee carpetbaggers" as "traitors to their race" and "not really proper white men", which fuelled their cause across the South, as their claims were seen as more justified. The fighting soon spread in all directions; the two regions that became particularly infamous, apart from the Alabama Black Belt, were the Low Country in South Carolina, and the Gulf Coast between roughly New Orleans and Tallahassee. For this reason, Seward split off the Military District of West Florida from parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida, the latter being renamed as East Florida. The new territory was to be occupied by a new army corps, made up largely of New Yorker and Pennsylvanian volunteers. Few people actually volunteered for service, knowing that they would be guarding their own countrymen from each other, and Seward briefly considered enacting the first peacetime draft in U.S. history. However, the measure was never put to the vote due to its unconstitutional nature, which may be the only saving grace of the Seward Administration's internal policy. Instead, he formed a new corps from parts of old ones, chiefly those stationed in the districts in whose territories the new district had been erected. This led to overextension, since those states (possibly excepting East Florida) were the ones where the fighting was the most intense.

Political cartoon from Harper's Weekly, decrying the Establisher goals as "worse than Slavery".

By the summer of 1866, the army of occupation was forced to use more and more harsh methods of policing the South, and Seward's popularity was rapidly declining. Many moderate Republicans, disgusted with Seward's policies toward Reconstruction (which they dubbed "Deconstruction") left the party and joined the Constitutional Union, for which they ran in the midterms; as a result, the Republicans lost their supermajorities in both houses, although retaining simple majorities in both. However, Seward still retained strong support among the radical Republicans, who believed that the Establishers were a danger to equality and the freedmen's freedom.

The Readmission Bill, in large part penned by Thaddeus Stevens, was put before Congress on May 18, 1867. It stipulated that all known ex-Confederates and half of the entire populations of all Southern states that wanted to rejoin the Union had to take the Ironclad Oath, by which they promised to never rebel against government authority again. The states also had to have "quelled all such military and paramilitary activity within its borders whose goals involve the active opposition to government authority". This bill was controversial, but was still passed and signed into law due to the radicals' control of the Republican Party and the Republicans' control of Congress. The only state readmitted by this act was Missouri, which had only very narrowly joined the Confederacy to begin with, and had significant Unionist sentiments within its borders even with the loss of Osage. Missouri was readmitted on April 4, 1868.

By the end of 1867, the situation in the South was almost beyond hope. The army of occupation had suffered debilitating casualties in fending off Establisher attacks, and many areas were seeing their local garrisons withdrawn, leading to spikes of violence in those areas. The army was forced to concentrate itself on major cities, and much of the countryside was overrun with Establisher guerrillas. Many a courier was sent out never to return, and the standard practice adopted after a while was to send as many as six couriers with the same message in order for any information to get around. The violence between races was also intensifying, with some weeks seeing as many as twenty lynchings in a single state. The Establishers never even attempted to hide their racism and their unwavering opposition against giving the blacks any more rights whatsoever than they had before the Civil War. This fact, almost alone, was what kept Seward in office over the vociferous protests of nearly everyone but the radicals. By March of 1868, the administration was contemplating allowing the use of more malicious counterinsurgency tactics such as the salting of farmland and destruction of telegraph lines. At this crucial time, an election was held, which put the fate of the occupied South in the hands of the voters…"

***

From "A History of America through its Presidents"

John Bachmann & Son, Bluefields, Nicaragua, 1945

"1868 presidential election

The election of 1868 was a hard-fought battle between the Republicans and the Constitutional Unionists, with the Democrats caught in the middle but chiefly supporting the Constitutional Unionists, over Seward's reckless policies toward the South. Many Southerners in the border states were enraged over the forcible selling of land to the freedmen, the army presence in the Confederate states to prevent segregation, the lack of compensation for the wartime burning of barns and crops, and a host of other issues. Even in the North, many people found that the road Seward pursued was much too hard on the South, and they wept over the destruction of the historic cities and landscapes of Virginia and Georgia, which little had been done to mend. However, there was also a prominent feeling that the South deserved punishment for initiating the war.

The Republican convention, held in Harrisburg on April 3, was a fairly quick affair. It was thought that avenging the war and creating a racially equal society came before fairly mending relations with the governments of the Southern states, and so Seward and Hamlin had no difficulty in getting re-nominated.

The Constitutional Union convention in Baltimore was another matter entirely. The delegates debated for three days over which candidates to put forth, with almost every state delegation having its own "favourite son" who they voted for. Eventually the debate settled down, and it was realised that someone from a large Northern state would be necessary to win the election, since mistrust of Southerners still ran too high for one to gain office. The convention eventually settled on the wartime Governor of Pennsylvania, Andrew Gregg Curtin, who had previously been a Republican, but had switched sides when Seward was elected and began imposing his own methods of reconstruction. For Vice President they nominated Francis Harrison Pierpont, the Governor of Vandalia, who was thought to be able to sway the Upper South.

Andrew Gregg Curtin, nominee of the Constitutional Union.

The Democrats had an equally hard time settling on candidates, but eventually decided on a dark horse, the Governor of Connecticut, James Edward English. For Vice President they selected Sanford Church, the former Lieutenant-Governor of New York. [2]

James E. English, Democratic nominee.

The campaigning was extremely harsh, an attribute which characterised many election campaigns of the era. The Constitutional Unionists and the Democrats attacked the Republicans for their harsh reconstruction policies, condemning Seward and his policies as "the Harrowing of the South", and blamed him personally for the civil and political strife that had plagued the South in the five years since war's end. In return, the Republicans condemned the Unionists and, especially, the Democrats as traitors and rebel sympathisers. Famously, the Hartford Post, which at the time was Republican-aligned, described English as "as much of a traitor as Tyler [3]". The Unionists and Democrats, however, were far from united in their efforts to oppose the Republicans, and quarrelled almost as much between one another, chiefly over economic policy, with the Unionists favouring protectionism to strengthen industry, and the Democrats continuing with their established free trade advocacy.

All three parties fared fairly well in the polls, with the Democrats lagging behind a bit, but still maintaining a good percentage of the popular vote. In the end, however, no candidate managed to gain the majority needed to win, Seward notoriously falling short by a single vote, and so, for the second time in United States history, the election was sent to the House of Representatives."

***

[1] Fahrenheit, of course. The US is still using it.

[2] So, why not Seymour? Well, IOTL he presided over the nominating convention, and repeatedly refused to accept, stating first that "I must not be nominated by this Convention, as I could not accept the nomination if tendered. My own inclination prompted me to decline at the outset; my honor compels me to do so now. It is impossible, consistently with my position, to allow my name to be mentioned in this Convention against my protest", and then (once several state delegations had announced that he was the only candidate they would accept) "I have no terms in which to tell of my regret that my name has been brought before this convention. God knows that my life and all that I value most in life I would give for the good of my country, which I believe to be identified with that of the Democratic party, but when I said that I could not be a candidate, I mean it! I could not receive the nomination without placing not only myself but the Democratic party in a false position. God bless you for your kindness to me, but your candidate I cannot be." When he had gone out to rest, the convention nominated him unanimously without him even knowing there was a ballot.

[3] IOTL, the Hartford Post wrote of Seymour as "as much of a corpse" as Buchanan, who had just died at the time. ITTL, with Buchanan losing, the quote instead recalls John Tyler, who died as a Confederate Congressman ITTL.

***

Last edited: