Chapter V, Part IV: Poniente, With Old Wars

The problem with Cuba solved, there were other things related with the Americas that the Spanish diplomacy decided to tackle soon.

One of them was the First Pacific War [1], which was theoretically still on-going in spite of the fact that no war action had taken place since 1866: basically, the last governments of Isabel II and both the Provisional Government and the governments that had searched for the new king and then fought the war against France had forgotten it due to more pressing problems. However, now they could do something, and the Sagasta government thought it was an excellent moment to attempt to establish better ties with the South American nations.

With the help of the United States, who was seeking a way to gain rapport with the resurgent nation, Spanish diplomats met with those of the South American alliance, formed by Chile, Bolivia, Perú and Ecuador. In the following Treaty of Tallahassee of 1875 (signed in the capital of the state of Florida), Spain recognised the independence of the four American nations in exchange of them opening their markets to Spanish products.

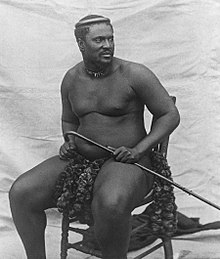

However, the years between the end of the war and the peace signing had taken their toll on the alliance, and now the nations were separating: Gabriel García Moreno, who had been President of Ecuador, would soon die at the hands of Colombian Faustino Rayo, and Ecuador drifted away from the other nations; Perú and Bolivia, which had once been part of the same nation, remained together, and Chile, which was emerging in the region as a powerful nation, was slowly starting to turn against its northern neighbours, which could become potential enemies in achieving regional supremacy.

Gabriel García Moreno, President of Ecuador

Sagasta saw this as a clear chance to divide the alliance and instead find some allies of its own in the southern hemisphere. After some considerations, it was decided that the best idea would be to pick Perú. This decision was not taken lightly: despite the fact that the war had initially started against Perú, there was still a pro-Spanish sentiment in the region, coming from the 1820s, when Perú was the last nation to become independent from Spain. Also, they had access to a great number of resources in the region, and if the Peruvian markets were opened to Spanish products, perhaps Spanish businesses could manage to even expand operations into. The guano deposits in the Chincha Islands, as well as the many natural resources in there, could be at hand. Of course, benefits would have to be shared with Perú, and probably they should build factories, but it was something they were willing to do.

Soon after this, two new buildings were built in La Paz and Lima, capitals of Bolivia and Perú, respectively: the Casa de España, ostensibly a place where all Spaniard people living in both nations could meet to remember their mother nation and encounter their compatriots, but it would also be used as the headquarters of the trade between Spain and both nations. Soon, one of the main articles both nations would be buying were weapons, both of German and Spanish production. The possibility of a war with Chile was near, and the allied nations wanted to make sure that such a war fell in their favour.

Casa de España in the city of Lima

The war did not take long to come. The nationalization, by part of Perú, of the nitrate mines in the department of Tarapaca, near the border with Bolivia, harmed Chilean interests in the region, as it left a great part of the nitrate resources in the region in the hands of the Peruvians (more than half of them, in fact). However, Chile only elevated complaints for the actions of the Peruvian government, and decided to concentrate in the Bolivian mines in the province of Antofagasta. The region was quite difficult to colonize by part of the Bolivians, as the mighty Andes stood in the way, and thus Chile had the way open for business expansion.

However, in 1878, the Bolivian government chose to use a loophole in a contract that had given the Chilean

Compañía de Ferrocarriles y Nitratos de Antofagasta the authorization to extract saltpeter from Antofagasta's mines without paying taxes, arguing that said agreement had not been approved by the Bolivian Congress. After a series of offers and counteroffers, the Bolivian Congress approved a 10 cent per 100 kilograms tax. The Chilean company asked for the support of its government, which argued that the tax was illegal, as per the Boundary Treaty of 1874, which, among other things, fixed the tax rates on Chilean companies operating in Bolivia for 25 years. In the end, Bolivia refused to back down, and threatened to confiscate the company's property.

The war started on February 14th 1879, the day when the Bolivian government auctioned the

Compañía de Ferrocarriles y Nitratos de Antofagasta's assets in Bolivia. That same day, 500 Chilean soldiers occupied the port city of Antofagasta, being welcomed by the mostly Chilean population in the city. Bolivia, however, did not declare war definitely until March 14th, asking the Peruvian government to do the same. Perú attempted to mediate in the war, trying to get both nations to the negotiating table, but Chile demanded immediate neutrality from Perú in the war, and, after not receiving confirmation of this, Chile officially declared war on Bolivia and Perú on April 5th.

Occupation of Antofagasta by Chilean soldiers

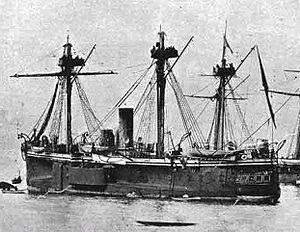

Most of the war, due to the fact that Antofagasta was next to the Atacama, the driest desert in the world, was fought in the seas, between the

Marina de Guerra de Perú and the

Armada de Chile. The former was led by the broadside ironclad

Independencia and the monitor

Huáscar, while the latter was led by twin central battery ironclads

Almirante Cochrane and

Blanco Encalada.

From left to right: Peruvian ships Independencia

and Huáscar

, and Chilean ships Almirante Cochrane

and Blanco Encalada

The Chilean navy blockaded the port of Iquique on the same day war was declared. The siege lasted for a month and a half, ending in the Battle of Iquique: there, Captain Miguel Grau demonstrated his great worth and ability, commanding the

Huáscar and managed to sink the Chilean corvette

Esmeralda. However, the victory was a pyrrhic one, for Perú lost the

Independencia as it persecuted the schooner

Covadonga.

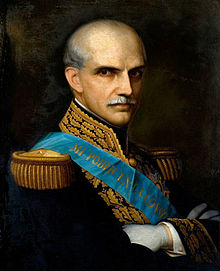

Miguel Grau Seminario, Admiral and future President of the Republic of Perú, and the Battle of Iquique

Despite the loss, it nonetheless allowed Perú to free the port of Iquique, and the subsequent months turned Miguel Grau into the hero of his generation, because, on board of the

Huáscar, he managed to hold off the Chilean Navy, participating in several fights in the Pacific. His genius stroke true with the capture of the steamship

Rimac, which was carrying a whole cavalry regiment: this was the biggest defeat so far in the war for Chile.

Due to this defeat, the Chilean government was forced to resign, as did Commander-in-Chief of the Navy Juan Williams Rebolledo, who was replaced by Commodore Galvarino Riveros Cárdenas: he started to devise a plan with which the Chilean navy would be able to trap the

Huáscar and give victory to Chile.

However, the capture of the

Rimac gave Perú time to deal with the problematic situation of its navy, and managed to buy two ironclads from Spain, with the possible options to obtain more of them if required. Sagasta and Prim decided to use this as a way to both intimidate Chile and gain new territories in the Southern Pacific, which could easily become part of another route between Spain and the Philippines should the two African routes (the Suez Canal and South Africa) be closed off.

Nine ships, led by the

Numancia and

Zaragoza ironclads, travelled from the port of El Ferrol to the Canary Islands, and from there to Iquique, making stops in Rio de Janeiro and the young but growing Argentinian town of Rawson, before crossing the Magallanes Straits and reaching Perú. Two of the ships would shed their Spanish colours to replace them with the Bicolour Banner, officially joining the Peruvian Navy, while the rest sailed west, making stops in some of the islands and archipelagos of the zone, such as the island of Pascua – where the natives signed a protectorate treaty with the Spanish admirals, who were amazed at the size of the statues that had been built by the natives' ancestors – or Salas y Gómez – a movement protested by the Chilean government, which had claimed the island for itself – before reaching the Carolinas, where some German ships were found and saluted. A small diplomatic incident nearly happened when it turned out that some of those ships were planning to claim the islands for the German Empire, but as soon as they realised their mistake, the Germans left without discussion.

The Numancia

and Zaragoza

ironclads

The two new ships – christened

Independencia, after the lost ironclad, and

Iquique – joined the Peruvian Navy in the nick of time. They managed to take part on the Battle of Punta Angamos of October 8th [2], where, although numbers favoured the Chileans, the greater ability of Miguel Grau gave victory to the Peruvians and preventing what could have been a land invasion of Chilean troops into Peruvian territory. The Chilean Navy also lost the

Blanco Encalada, which would be marked as the start of the end of the war.

After achieving naval supremacy following another battle in front of Antofagasta, the Peruvian Army and Navy achieved a landing of troops nearby the city of Antofagasta, keeping them supplied from Iquique and taking the city from the beleaguered Chileans, after a battle where, according to accounts, more casualties were caused by the heat and humidity than by the bullets shot by the soldiers.

From Antofagasta, the Peruvian soldiers started to march towards the east in an attempt to take the desert forts spread along the Atacama desert, a task that would have been hard at any time of the year, but became harder due to the high temperatures typical of the Southern Hemisphere's summer. Bolivian troops also marched from the east, and, after two months of march and battle, all Chilean troops were dead or prisoners of the allied armies.

The Atacama Desert: I'm getting thirsty just for looking at it...

Meanwhile, Miguel Grau had not remained quiet: his fleet attacked the Chilean coast, forcing their navy to attempt to stop them, an attempt that saw the loss of the

Almirante Cochrane, Chile's remaining ironclad, in a battle that happened on November 15th in front of the city of Valparaíso.

The last event of the war was a landing by a mixed Peruvian-Bolivian army on the city of Copiapó, which took the city on January 20th of 1880. By then, most Chilean cities were demanding that the government put an end to the war, which they had to acquiesce, and asked the Peruvian-Bolivian alliance for an armistice.

Under the auspices of the United States and United Kingdom, a peace treaty would be signed on March 1st in Quito, Ecuador. Territorially, the situation was

statu quo ante bellum, that is, there would be no exchange of lands. However, economically, things were different: Chile was forced to accept Bolivia's expropriation of the

Compañía de Ferrocarriles y Nitratos de Antofagasta, which had started the war, accept the change of taxes for the Chilean companies and pay a compensation to both Perú and Bolivia.

In spite of Bolivia being the most benefited economically, the great winner of the war was Perú, which had established its supremacy in the south-eastern Pacific, and which found itself in a great euphoria following the victory. Miguel Grau Seminario, ascended now to the rank of Admiral, would be also elevated to the rank of

Héroe de la República [3], and would, in 1884, be voted in a landslide to become President of the Republic, using his position to direct Perú towards modernization, so that their regional supremacy could be upheld.

[1] The Chincha Islands War.

[2] In RL, this battle ended with Chilean victory and the death of Miguel Grau Seminario. Things were then much more lopsided towards the Chilean fleet, which had 4 warships and 2 transports against the Peruvian fleet, with only 2 warships.

[3] Miguel Grau Seminario remains, to this day, one of the most important figures of Peruvian history. In RL, he was recognised as the most important Peruvian of the Millenium, and, as he was a member of the Congress of the Republic of Perú, to this day his seat remains preserved in the Congress, with all congressmen and women responding "present" when Grau is called.