Zemsta Za Nóż w Plecy - The Polish Volunteers in Finland

Zemsta Za Nóż w Plecy - The Polish Volunteers in Finland

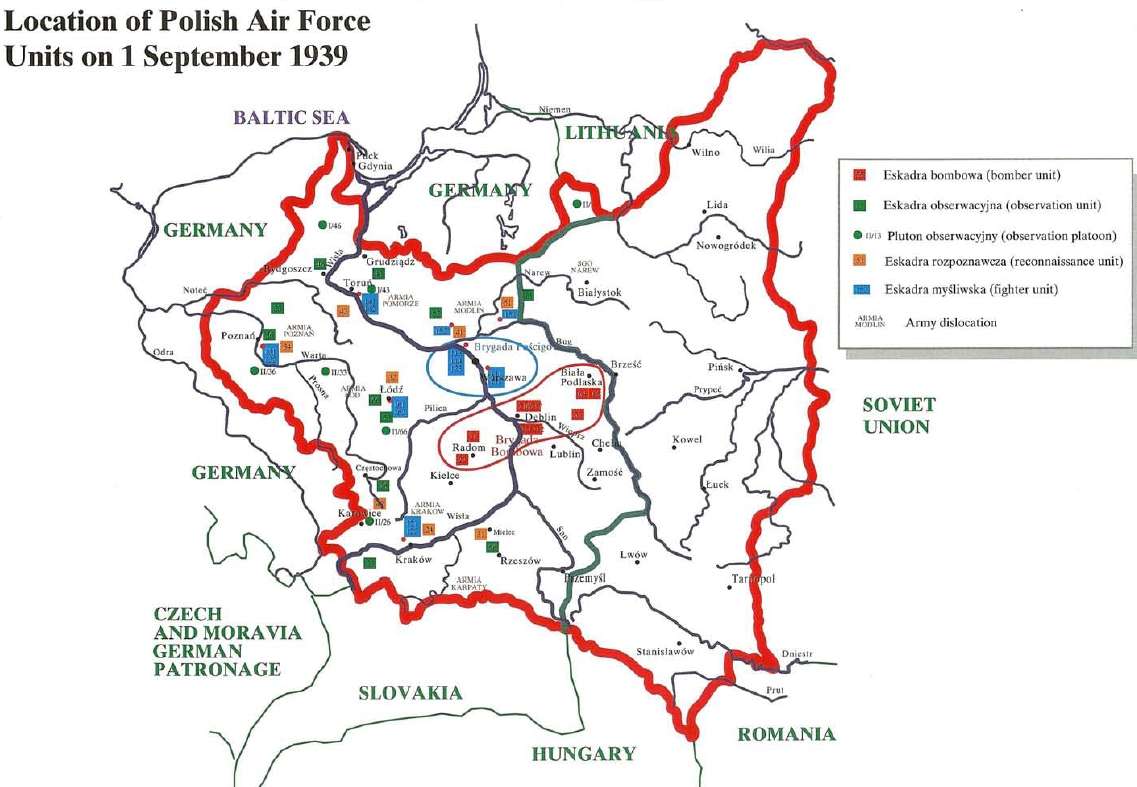

In an earlier Post, it was mentioned that in November 1939, there were already two foreign contingents in Finland that had been formed in Finland from Polish soldiers evacuated by the Merivoimat from Lithuania and Latvia in late September and early October after the fall of Poland. The Merivoimat had, in the face of direct opposition from both the USSR and Germany, done what nobody else could have done, and evacuated some 30,000 Poles from Latvia and Lithuania to Finland. In addition, Polish warships, submarines and a number of Polish Airforce aircraft had found safety and refuge in Finland. With the agreement of the Polish Government-in-Exile in London, the warships and aircraft had been incorporated into the Finnish military until such time as they could be transferred to the UK and France to resume the fight.

Arrangements were in progress through October 1939 to have the men themselves shipped out of Finland via Petsamo to the UK, from where they could join the British or French and resume the fight. However, with the rapid escalation of the situation between the USSR and Finland through October and November, events overtook the plans and under the circumstances of the Soviet attack on Finland, the Polish Government-in-Exile agreed that all Poles in Finland who volunteered to fight could stay. Almost to a man, the vast majority of the Poles in Finland had volunteered. The Poles with air force or naval experience were allocated to the Ilmavoimat or Merivoimat as appropriate, while the soldiers were assigned to six Regimental Battle Groups, loosely grouped into two Divisions. These two Divisions would be joined in April 1940 by the Polish Second Infantry Fusiliers Division (15,830 soldiers), shipped in from France and commanded by Brigadier-General Bronisław Prugar-Ketling. In une 1940, after the Allies retreated from Narvik, the Polish Independent Highland Brigade under Zygmunt Bohusz-Szyszko would join the Polish Volunteers in Finland.

Where we have not already done so, we will now look at these units as well as the Polish warships and Polish aircraft that would fight with the Finns against the USSR in the Winter War.

The Polish Navy-in-Exile in Finland

With the fall of Poland to both Germany and the Soviet Union in September 1939, a number of ships and submarines of the Polish Navy had escaped to Finland – something that had quietly been arranged between the two governments earlier in 1939 as a somewhat remote contingency plan that neither country expected to eventuate. The Polish Navy in 1939 was not large. The coastline was relatively short and included no major seaports. In the 1920s and 1930s, such ports were built in Gdynia and Hel, and the Polish Navy was built up under the leadership of Counter-Admiral Józef Unrug (CO of the Fleet) and Vice-Admiral Jerzy Świrski (Chief of Naval Staff), with ships acquired from France, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, and the Navy.

The Naval War Plan was primarily focused on securing Polish supply lines in case of a war against the Soviet Union and it was wih a war with the USSR in mind that most Polish war planning had been carried out. By September 1939 the Polish Navy consisted of 5 submarines, 4 destroyers, and various support vessels and mine-warfare ships. This force was no match for the large German Navy and in the event of war with Germany an alternative strategy of harassment and indirect engagement was planned (the “Peking Plan”). In the case of a war with Germany, the Polish Naval base at Gdynia was clearly likely to be overrun or rendered useless by air attack and the Peking Plan was created in order to remove the Destroyer Division (Dywizjon Kontrtorpedowców) from the immediate operational theatre and needless loss in the event of war with Germany. The Kriegsmarine had a significant numerical advantage over the Polish Navy and the Polish High Command realized that the ships which remained in the small and mostly landlocked Baltic were likely to be quickly sunk by the Germans. Also, the Danish straits were well within operation range of the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe, so there was little chance for the plan to succeed if implemented after hostilities began.

Originally intended to cover the withdrawal of three destroyers of the Polish Navy, the Burza ("Storm"), Błyskawica ("Lightning"), and Grom ("Thunder") to the United Kingdom, this Plan had been amended in early 1939 as a result of negotiations conducted between Marshal Mannerheim, the Polish Prime Minister, Major General Składkowski and the Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Forces, Marshal Edward Smigly-Rydz. While the early version of the Plan had focused on moving the newer Destroyers to the UK, the revisions made following the informal agreement with Finland made provision for the smaller warships and submarines to escape to Finland, something that was within their capabilities, whereas escape from the Baltic entirely was not (with the exception of the submarines). This agreement was undocumented and informal, but the arrangement was that in the event of either country being involved in a war with the USSR, each would assist in whatever way they could and provide a refuge for the others ships, aircraft and soldiers in the event of defeat.

The mounting strain in European politics reached a new tension-point in March 1939, with the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia - first, with the German-inspired secession of Slovakia, and then with the Bohemia "protectorate" enforced upon her at a gun-point. Soon after the "independent" Slovakia also asked to become a German protectorate, and Hitler, at the peak of his diplomatic successes, extorted Klaipeda from Lithuania, and voiced territorial claims in Poland, to which Poland answered with stern refusal. On 18 March 1939, three days after the occupation of Bohemia and Moravia, while German preparations to annexate Klaipeda were under way, the Polish Navy was put on partial alert. The alert concerned primarily the destroyer squadron and the submarine squadron - the only forces of the Polish fleet of considerable combat value, which could be actively engaged in hostilities. Another large Polish warship, the heavy minesweeper Gryf, was kept in reserve. The Polish measures were not entirely unjustified - on 23 March a strong convoy of German ships heading for Klaipeda passed closely along the Polish coast en route from Germany to East Prussia. Under the escort of destroyers and trawlers, the battleship Deutschland carried the Chancellor of the Third Reich himself. After Klaipeda was incorporated into the Reich, the convoy returned along the same route, sparking fears that Hitler, intoxicated with another easy success, would decide to enter Danzig and triumphantly proclaim the return of the city and the whole territory of the Free City of Danzig to Germany. Polish naval ships remained on alert and the Polish outpost on the Westerplatte peninsula in Danzig was also readied to repel any hostile actions of Danzig Nazis. However, this time the German fleet returned to its bases.

In April 1939 political tensions eased and the Polish warships also returned to their bases for maintenance. The submarine squadron was reinforced by a new unit – the submarine Sęp, twin-sister of the Orzeł, had been commissioned in February 1939 amidst an enthusiastic reception following her arrival from the Netherlands. Sęp arrived unfinished, since the Polish command was afraid that on the outbreak of a war she might be trapped. The Poles anticipated that Sęp would return to Rotterdam for further fitting out as soon as the strains in the political situation were eased. Also at this time work on fortifications along the Polish coast and on the Hel peninsula were started. The Polish government opened talks with France and Italy concerning delivery of modern coastal artillery (230mm guns) and also consulted with the Finnish Coastal Defence Forces, whose expertise in this area was well known. As the talks stalled, the Poles approached the British asking them to send a monitor fitted with 381mm guns to the Baltic, but that initiative also failed.

In the summer of 1930, the activities of the Kreigsmarine in the Baltic intensified, as did the volume of merchant shipping between Germany and East Prussia.

The commander of the Polish destroyer Wicher, Captain Stefan de Walden, noted on this occasion:

“At that time our ships conducted round-the-clock duties in turns, during which the task of the ship on duty was to observe the activities of the German ships on the routes leading to East Prussia, as well as estimate, if possible, the type and quantity of the cargo they carried. Needless to say, we also closely observed the movements of the warships, and used to send detailed reports to the Fleet Headquarters immediately after passing the duties to the next ship. In their turn Polish ships, and especially the ship currently on duty, were under close observation of the swastika-marked aircraft, and it used to happen that this or that destroyer or cruiser showed interest in a Polish ship, which could be detected from their manoeuvres and general behaviour.

During such encounters both ships, as a rule, were on alert, having guns and torpedo tubes aimed at the counter-part. Simultaneously they minded respectful distance, which did not require a gun-salute, which could have grave consequences in the circumstances, when both ships aimed at each other. To use a rough naval saying - we were "sniffing" each other. It was an excellent opportunity to train the crews in bearing the elements of a target; a target, which at any time, at any second, might become a real combat target.”

The Polish Navy’s submarines were also kept busy with training and on various exercises preparing them for war, whose inevitability the Navy - due to constant contact with the soon-to-be enemy - was generally expected. While at sea, Polish submarines often found them-selves being used as targets for simulated attacks by German aircraft or submarine chasers – it was no wonder that their crews more often than their colleagues in the surface ships, or in other service branches, had the feeling that open war was just a matter of time.

Captain Włodzimierz Kodrębski thus summarized the atmosphere of those days:

“It rarely happened that ships stayed in ports; switching services to wartime routine ("combat watches"), patrolling and anti-air alert were permanent, and leaves were granted only by day, and only for few hours. Everybody gradually started getting weary of the wartime service conditions, without any satisfaction, since it was forbidden to shoot annoying planes and boats, which followed us everywhere. We were similarly helpless, when we watched Germans sending regular convoys of ships full of troops and war materials to East Prussia. And the real berserk got to all of us one morning, when from the Hel roadstead we saw the German battleship Schleswig-Holstein entering Gdańsk upon the consent of the government of the Republic of Poland, and greeted cheerfully by the hitlerised townfolks.”

Photo sourced from: http://www.militaryfactory.com/ships/im ... lstein.jpg

The German battleship Schleswig-Holstein entering Gdańsk The German battleship was ostensibly on a courtesy visit, but her real task was to take part in the invasion of Poland, according to the Fall Weiß plan. The Germans expected that the war with Poland would be a local conflict, since a Polish-Soviet rapproachment had never taken place and the Western democracies showed no real determination to commit to the Polish cause.

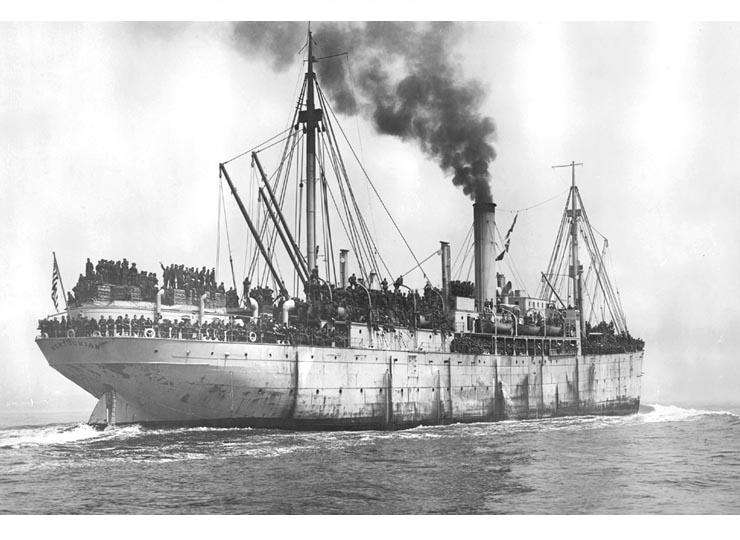

Prior to Poland being attacked by Germany, Mannerheim had, outside the normal government channels, contacted both Składkowski and Smigly-Rydz and informed them that Finland considered the arrangement to include the current situation. Lacking numerical superiority, Polish naval commanders decided in late August to execute the Peking Plan. The Burza ("Storm"), Błyskawica ("Lightning"), and Grom ("Thunder") were ordered to escape the Baltic and make for Lyngenfjiord or Petsamo, while the Wicher (“Gale”) and the heavy minelayer ORP Gryf were ordered to make for Finland in company with the Polish navy’s smaller Minelayers and Minesweepers, the frogman support ship ORP Nurek, the school of naval artillery ship ORP Mazur and two mobilized patrol boats of the Border Guard, the ORP Batory and the ORP Kaszub. The orders came as somewhat of a surprise to the ships Captains and crew - For six months then they had been preparing for the defence of Polish territorial waters, and now they were to abandon them. The Polish Navy’s five submarines were ordered to undertake whatever action against the Kreigsmarine was possible and then proceed to either the UK or Finland at the CO’s discretion.

Initially, Marshal Edward Smigly-Rydz, Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Forces had resisted the implementation of the Peking Plan but he finally agreed., largely due to the plan for a Romanian Bridgehead. It was hoped the Polish forces could hold out in the southeast of the country, near the common border with Romania, until relieved by a Franco-British offensive. Munitions and arms could be delivered from the west via Romanian ports and railways. The Polish Navy outside the Baltic would then be able to assist in escorting the ships delivering military supplies to Romanian ports. As the tensions between Poland and Germany increased, the Commander of the Polish Fleet, Counter Admiral Józef Unrug signed the order for the operation on 26 August 1939, a day after the signing of the Polish-British Common Defence Pact; the order was delivered in sealed envelopes to the ships. On 29 August, the fleet received the signal "Peking, Peking, Peking" from the Polish Commander-in-Chief, Marshall Śmigły-Rydz: "Execute Peking". At 1255 hours, the ships received the signal via signal flags or radio from the signal tower at Oksywie, general quarters were sounded the respective captains of the ships opened the envelopes, and departed at 1415.

The Fleet split into two. The destroyers Błyskawica (commanded by Komandor porucznik Włodzimierz Kodrębski), Burza (commanded by Komandor podporucznik Stanisław Nahorski) and Grom (commanded by Komandor porucznik Włodzimierz Hulewicz) weighed anchor, formed and line and steamed towards Hel at 23 knots, heading for the Baltic exit under the command of Komandor porucznik Roman Stankiewicz. As soon as the squadron made away from the coast and the range of the observation posts, it changed its course again, making towards Bornholm in an attempt to evade German observation. This didn’t work - the German submarine U-31 (Lt.-Cdr. Johannes Habekost) from the squadron detached to trace the movements of the Polish fleet, spotted the Polish destroyers some 30 miles north of Rozewie and - undetected by the Poles - radioed their position to the German command in Swinemunde. Secondly, on the way to Bornholm the Polish destroyers passed a German passenger liner from the Seedienst Ostpreußen transporting German troops to East Prussia. It is not known whether the transport reported the position of the Polish ships, but since the encounter took place in broad daylight, there is little doubt that they were spotted.

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... Peking.jpg

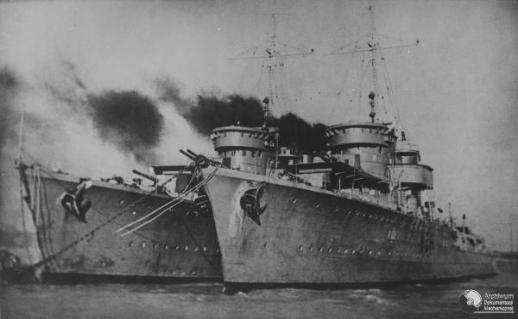

Polish destroyers during execution of the Peking Plan. View from ORP Blyskawica of ORP Grom and ORP Burza / Polskie niszczyciele płynące do Wielkiej Brytanii w ramach planu "Peking" - widok z rufy ORP Błyskawica na ORP Grom i ORP Burza.

As the Polish destroyers approached the Danish straits, another encounter took place close to the Falsterborev lightship, this time with unidentified warships steaming from the straits southward. Although the Polish commanders agreed that these might be Danish ships (a gunboat and a torpedo boat), the ships were blacked out, which aroused understandable concern and called for caution. The outbreak of the war was expected momentarily, a potential enemy could turn into a real one any time, and torpedoe tubes on the Polish destroyers were kept ready in case of any attack. Nevertheless, the two squadrons passed each other and disappeared in the darkness. It was not until many years later that it became known that the ships the Polish squadron encountered on that night of 30/31 August 1939 were actually the Kreigsmarine cruisers Köln and Königsberg with an escort of destroyers. What is more, the Germans knew whom they had encountered, while the Poles were left to more or less guess that the encountered squadron might be German, although they were not able to identify them positively.

The Polish warships passed the Falsterborev and around midnight entered the Øresund, full of shallows and banks, forcing a reduction in speed to 16 knots. It was the most difficult stage of the voyage, since the Poles were forced by the Danish regulations regarding foreign warships steaming in Danish territorial waters to take the more difficult of the sea routes through the Sund: the Flintrinne passage. Soon after, when only a few miles away from the Skagen lighthouse, the Polish squadron was spotted by German aircraft which followed until nightfall, when the Poles turned towards the Norwegian coast, and from there headed out into the North Sea. In the evening of 31 August the Polish squadron was also spotted from the German submarine U-19. The German conduct was correct and without any provocative action as there still was no state of war between Germany and Poland.

The small squadron changed course towards Norway in order to shake off the pursuit during the night. The ships entered the North Sea, and at 0925 on the morning of 1 September learned about the German invasion of Poland. At 1258 that day, they encountered the Merivoimat destroyer FNS Jylhä which had been sent south from Lyngenfjiord to meet them. Each of the three destroyers received a Merivoimat liaison officer together with Merivoimat signals personnel and were reflagged under the Merivoimat Naval Ensign. The crews were immediately sworn in as Finnish Citizens (with a special dispensation as per the Act of the Parliament passed on 1 Sepetember 1939, permitting dual Polish-Finnish citizenship for members of the Polish military). Two days later, at 17:37 on 3 September 1930, they dropped anchor in Lyngenfjord. Thoughtfully, the first deliveries to the three ex-Polish destroyers were complete sets of Merivoimat dinnerware for the Officers Messes.

Merivoimat dinnerware - plate

Merivoimat dinnerware – plate backstamp – manufactured by the Arabia Porcelain Factory

Photo sourced from: http://www.polishgreatness.com/sitebuil ... 72x269.jpg

The Polish Destroyer ORP Blyskawica anchored in Lyngenfjiord harbour – October 1939. ORP Blyskawica was commanded by Lt. Cmdr. Włodzimierz Kodrębski.

Photo sourced from http://img.audiovis.nac.gov.pl/PIC/PIC_1-W-2090-1.jpg

Photo from August 1935: Wizyta niemieckiego krążownika "Konigsberg" w Polsce: Przedstawiciele załogi krążownika "Konigsberg" oraz witający ich wojskowi przed samolotem na lotnisku Okęcie. Widoczni m.in. komandor Hubert Schmundt (4 z lewej), niemiecki attache wojskowy gen. Max Schindler (2 z lewej), komandor Kodrębski (1 z prawej) / Visit of the German cruiser "Konigsberg" to Poland: Representatives of the crew of the cruiser "Konigsberg" being welcomed. Visible among others are Captain Hubert Schmundt (4th left), the German military attache, General Max Schindler (2nd left), Commander Kodrębski, Polish Navy (1st, right)

Photo sourced from: http://www.polishgreatness.com/sitebuil ... 18x319.jpg

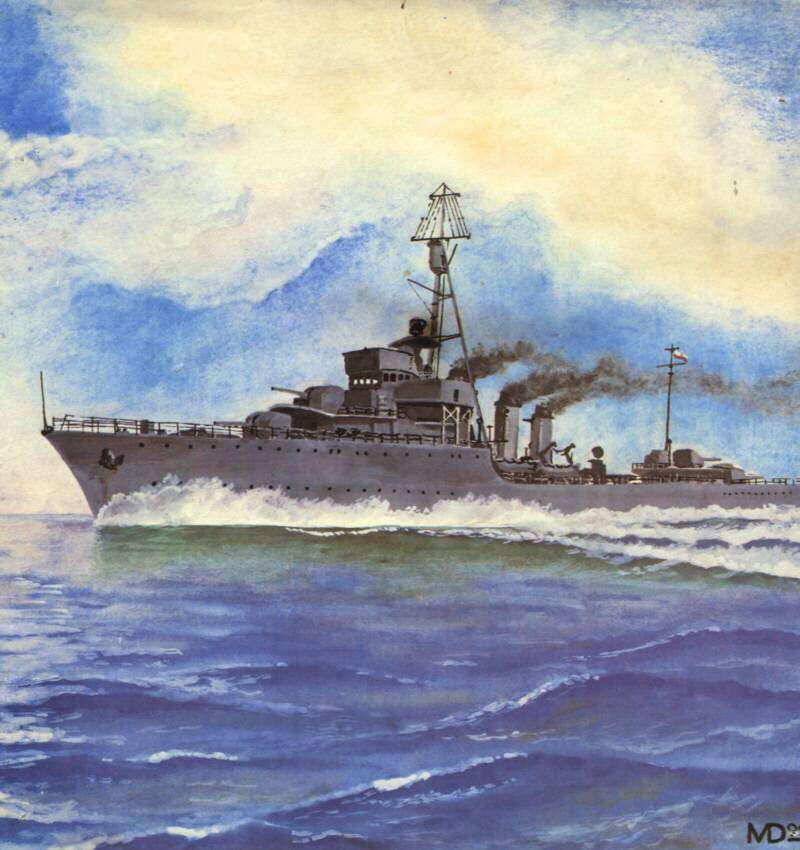

The Polish Destroyers ORP Blyskawica and ORP Grom tied up together in Lyngenfjiord. ORP Grom was commanded by Komandor porucznik Włodzimierz Hulewicz. The Polish Navy’s Grom-class destroyers built by the British company of J. Samuel White, Cowes.They were laid down in 1935 and commissioned in 1937. The two Groms were some of the fastest and most heavily-armed pre-World War II destroyers. Despite having ordered its previous pair of destroyers (ORP Burza and ORP Wicher) from France, a country with which it had strong ties, Poland decided to acquire the second pair from the United Kingdom, possibly in recognition of the excellence of British destroyer designs at the time. The selected design resulted in large and powerful ships, superior to German and Soviet destroyers of the time, and comparable to the famous British Tribal class of 1936. The main armament was changed from the 130 mm used on the Wicher-class destroyer to the standard British destroyer calibre of 4.7 inch (120 mm). However, the guns were not British, but rather the Swedish Bofors 50cal QF M34/36, the same as those used previously on the minelayer ORP Gryf.

As was mentioned in an earlier Post on the Merivoimat, Finland had licensed the design for the Grom-class destroyers from the Polish Government even before construction of the Polish orders had started, an arrangement that suited both parties, although the Finnish Navy modified the design somewhat, reducing the number of 120mm guns and substantially increasing the anti-aircraft armament. The Finnish Navy Grom-class destroyers Jylhä and Jyry were commissioned in 1936 and 1937 respectively. Jymy and Jyske were delivered in mid-1938, Vasama and Vinha in mid-1939 and Viima and Vihuri in late 1939. A further 6 destroyers of this class would be constructed following the end of the Winter War and prior to Finland’s re-entry into WW2 in early 1944.

Photo sourced from: http://www.computerage.co.uk/navy/pic/burza.jpg

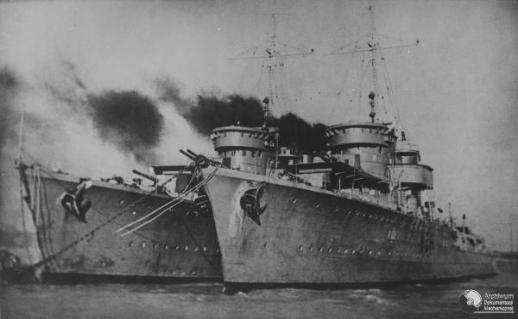

The Polish Navy’s Wicher-class destroyer ORP Burza (Storm), commanded by Komandor podporucznik Stanisław Nahorski, en route to Lyngenfjiord: ORP Burza and her sister ship, ORP Wicher, were ordered on 2 April 1926 from the French shipyard Chantiers Naval Francais. She entered service in 1932 (roughly 4 years after the scheduled delivery date), and her first commander became Kmdr Bolesław Sokołowski. On 30 August 1939 the Polish Navy’s destroyers and submarines were ordered to execute the “Peking Plan”, and headed for Lyngenfjiord or Finland as their orders indicated. Burza fought with the Merivoimat against the Soviet Navy in late 1939. In April 1940 she was part of the Helsinki Convoy Escort as the Convoy entered the Baltic. She saw action againts the Kreigsmarine and then served as part of an FNS Baltic Convoy Escort Group for the remainder of the Winter War. After the Winter War, Burza became a Merivoimat Training Ship and then in 1944 she was transferred back to the Polish Navy and became a submarine tender for Polish submarines. At the end of WW2 she returned to Gdynia where she was later overhauled, remaining in serviced until 1955. In 1960, she became a museum ship. After Błyskawica replaced her in that role, she was scrapped in 1977.

Photo sourced from: http://img.audiovis.nac.gov.pl/PIC/PIC_1-W-353.jpg

Komandor podporucznik (Lieutenant Commander) Stanisław Nahorski, Captain of ORP Burza.

The remainder of the Fleet, led by the destroyer Wicher and under the overall command of Wicher’s CO, Stefan de Walden, steamed for Finland on the same day, with the minelayers hastily deploying their final loads of mines to augment the minefields already laid. Accompanying the Wicher were the heavy minelayer ORP Gryf commanded by Stefan Kwiatkowski, the six small ships of the Minelayer/Minesweeper Flotilla (Flotylla Minowców), composed mostly of the so-called birdies (ptaszki, a nickname coined after the fact that all of the Jaskółka class ships were named after a different species of bird), the frogman support ship ORP Nurek, the school of naval artillery ship ORP Mazur, a small patrol boat of the Border Guard, the ORP Batory and two obsolete gunboats, the ORP Generał Haller and ORP Komendant Piłsudski. It was a sizable little flotilla and at the maximum speed of the slowest ship,

Photo sourced from: http://www.biurodabrowski.republika.pl/wicher.jpg

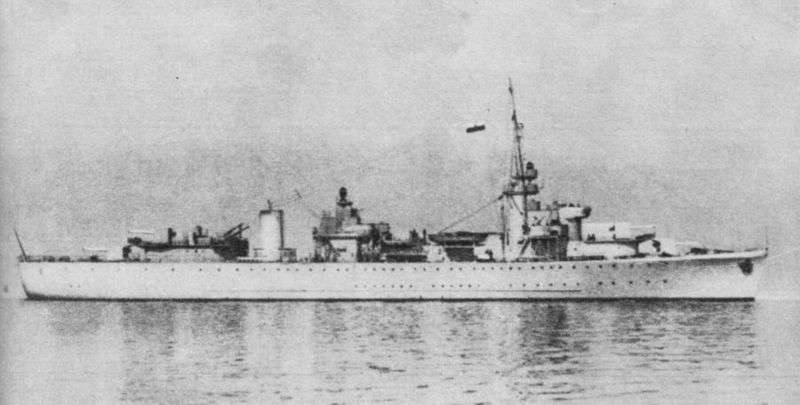

ORP Wicher at speed in the Baltic Sea, 30 August 1939: ORP Wicher was commissioned into the Polish Navy on 8 July 1930 and was the first modern ship of the Polish Navy. During the Interbellum, Wicher served a variety of roles, mostly political. For instance, on 15 June 1932, she was sent to the port of the Free City of Danzig (Gdańsk) to meet two British destroyers entering the port and to underline the Polish political influence in that city. In March 1931 she sailed to Madeira, from where she brought the Marshal of Poland Józef Piłsudski and his family back to Poland. She also visited Stockholm in August 1932, Leningrad in July 1934, Kiel in June 1935 and Helsinki and Tallinn the following month.

Photo sourced from: http://aj-press.home.pl/images/rekl/eow28_s_85.jpg

ORP Wicher and her sister ship ORP Burza side by side at Tallinn (Estonia) harbour during the goodwill visit of July 1935.

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... finder.JPG

Range-finder of the Polish destroyer ORP Wicher. Photo from 1931. Wicher could reach a maximum speed of 33.8 knots, had a crew of 162 and was armed with four 130 mm Schneider-Creusot Model 1924 guns (4xI), two 40 mm Vickers - Armstrong AA guns (2xI), four torpedo tubes 550/533 mm (2xII), two depth charge launchers, two Thornycroft depth charge throwers and 60 mines. By the late 1930s it was apparent that the armament was insufficient. The French guns had a low rate of fire and the ship had inadequate protection against aerial bombardment. To partially solve the problem, in the autumn of 1935 two additional double 13.2 mm Hotchkiss heavy machine guns were added.

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... P_Gryf.jpg

The heavy minelayer ORP Gryf (Griffin), commanded by Stefan Kwiatkowski. Laid down in 1934 at the French shipyard Chantiers et Ateliers A. Normand in Le Havre, she was launched in 1936. Built to Polish specifications, she was intended as a large minelayer with an armament close to that of a destroyer. Powered by two Sulzer 8SD48 engines of 6,000 horsepower (4,500 kW) each, she was capable of 20 knots (37 km/h/23 mph), fast for her size. She also had a remarkably long range of roughly 9,500 nautical miles (17,600 km) at 14 knots (26 km/h). As the Polish Navy was small and no other state expressed a need for such a vessel, she remained the only ship of the class. Whiler her usual complement of crew was 162, she also served as a school ship and could take on board up to 60 additional students. Her armament consisted of 6 × 120 mm (4.7 in) Bofors wz. 34/36 guns (2 × 2 and 2 × 1) in four turrets, 4 × 40 mm (1.6 in) Bofors wz. 36 AA guns (2 × 2), 4 × 13.2 mm (0.52 in) Hotchkiss wz. 30 HMG's (2 × 2) and 8 × naval mine racks, with up to 600 mines. With her heavy load of mines, she would prove a remarkably useful addition to the Merivoimat in the Winter War.

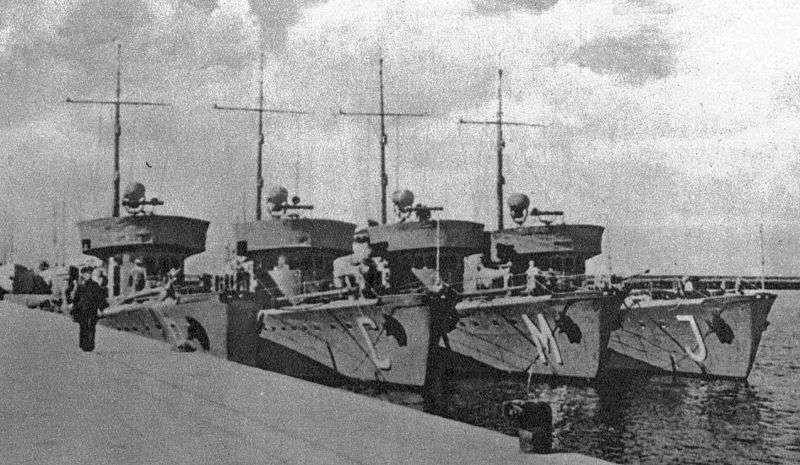

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... taszki.jpg

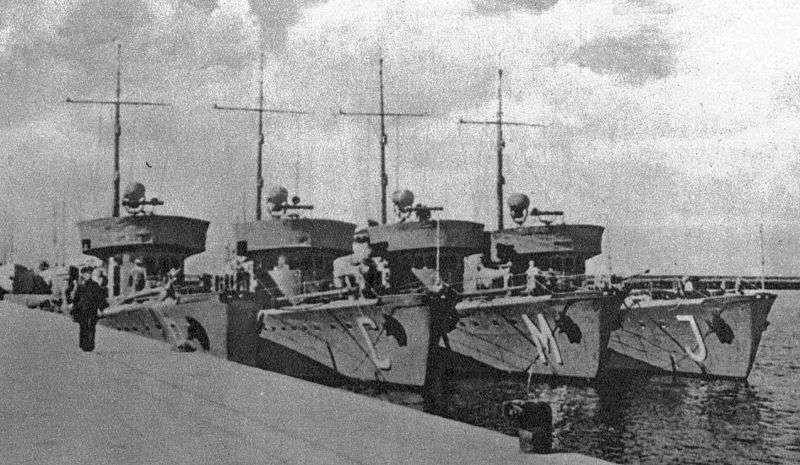

The Polish minesweepers OORP Rybitwa, Czajka, Mewa, Jaskółka in 1937 The six small ships of the Minelayer/Minesweeper Flotilla (Flotylla Minowców) were of the Jaskółka class, built during the 1930's. They were the first sea going warships to be built in Poland and were of a versatile design allowing the ships to serve in the role of either a minesweeper, small minelayer or a sub chaser. All were named after birds, therefore the class was nicknamed: ptaszki (birdies) in Polish. The first 4 ships of the class were built at Gdynia in the Modlin shipyard. After they entered service they proved to be a good design so a further 2 were ordered in the mid 30s. They had a maximum speed of 17.5 knots, displaced 183 toms, had a crew of 30, were powered by 2 shaft diesel engines, 1040 BHP with a length of 45m and a beam of 5.5m. They were armed with 1 x 75mm or 76mm, 2 x 7.92mm machineguns and could carry 20 mines or depth charges.

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... el_bok.jpg

A model of ORP Jaskółka in the Pomorskim Muzeum Wojskowym. Jaskółka was under the command of Captain Tadeusz Borysiewicz. Of the other warships in this class, ORP Żuraw was under the command of Capt Mjr. Robert Kasperski, ORP Rybitwa was under the command of Lieutenant Commander Kazimierz Miładowski. The CO’s of Mewa, Czajka and Czapla are not recorded.

Photo sourced from: http://forum.valka.cz/files/orp_nurek_2_509.jpg

Photo sourced from: http://www.computerage.co.uk/navy/pic/jaskolka.jpg

ORP Jaskółka in action with the Merivoimat, Gulf of Finland, Summer 1940

The Polish Navy’s diver support ship ORP Nurek, a small ship, displacing only 110 tons and with a length of 26.5m and a beam of 5.8m. Her maximum speed was 10 knots. In the early 1930's the Navy with decided to build a modern ship to support naval divers, who made do with an old and battered support boat (a British M-52, purchased from surplus, which has been given the name "Nurek" (Diver) in 1922). After long deliberation, a design from engineer A. Potyrała was accepted. In the second half of 1935 construction started at the naval shipyard in Gdynia. This was an indication of the development of this yard, only a few years earlier, all orders received had of necessity, to be completed in the Gdansk Shipyard. In July 1936 the ship was completed. By order of the Minister of Defense she was named ORP "Diver". Her entry into service took place on 1 November 1936. The ship was equipped with a decompression chamber of Polish construction, a diving pump, winch and radio. Her commander was Warrant Officer W. Tomasiewicz. Until the outbreak of war and the execution of the Peking Plan, the ship served as a base for underwater work and training of Polish Navy divers.

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... /Mazur.jpg

ORP Mazur was a former German torpedo boat (V-105). Originally built in 1914 by Stettiner Maschinenbau A.G. Vulcan in Stettin, Germany to meet an order for the Netherlands Navy (as Z-1, along with three sisterships Z-2, Z-3 and Z-4), she was confiscated by Germany and commissioned as torpedo boat V-105. During the division of German naval ships in December 1919, Poland was assigned only six torpedo boats, largely due to a reluctance of the British to strengthen new born navies. The V-105 was first assigned to Brasil, but then bought by a British dockyard and finally exchanged with Poland for another torpedo boat, the A-69, in 1921, for an extra charge of £900 to the Poles. Poland also received her sistership, V-108 (later the Polish ORP Kaszub), and four smaller torpedo boats. V-105 was in bad condition and after some repairs in Rosyth, in September 1921 she was towed from Great Britain to Gdańsk. After a refit, she was commissioned in the Polish Navy on August 2, 1922 under the name ORP Mazur. She served in the Torpedo Boat Unit (Dywizjon Torpedowców) with the identification letters MR. In 1931 she was rebuilt as a gunnery training ship and her armament was updated. In 1935 she underwent a modernization program and was returned to service in 1937. She displaced 421 tons fully loaded, had a length of 62.6m and a beam of 6.2m, had a maximum speed of 27 knots and a range of 1,400 nautical miles (2,600kms) at 17 knots. With a crew of 80, she was armed with 3 × Schneider 75 mm (3.0 in) guns, 1 x Vickers 40,, AA gun and 2 machineguns.

Photo sourced from: http://img.audiovis.nac.gov.pl/SM0/SM0_1-P-3549-9.jpg

14 July 1937: Prezydent RP Ignacy Mościcki na mostku kapitańskim na ORP "Mazur". Widoczni także m.in.: kontradmirał Jerzy Świrski (na lewo za prezydentem), adiutant prezydenta RP kapitan Stefan Kryński (na lewo od kontradmirała Świrskiego), dowódca Zamkowego Szwadronu Żandarmerii kpt. Jan Huber (stoi przed kpt. Kryński) / Polish President Ignacy Mościcki on the bridge of ORP "Mazur". Also in the photo are: Admiral Jerzy Świrski (to the left of the president), the Polish President's adjutant, Captain Stefan Krynski (left of Admiral Świrski), the commander of the Squadron Castle Police Cpt. Jan Huber (standing in front of Cpt. Kryński)

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... r_75mm.jpg

The two bow 75 mm guns of the Polish artillery training ship ORP Mazur (a former German torpedo boat) ater her refit in 1937

Photo sourced from: http://images.okazje.info.pl/p/sport-i- ... -wz-39.jpg

ORP Mazur under attack by Soviet aircraft, December 1939, Gulf of Finland.

Picture sourced from: http://wielkamalaflota.blox.pl/resource ... 01x558.jpg

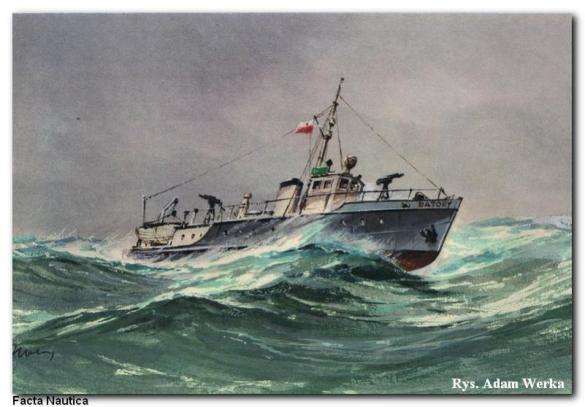

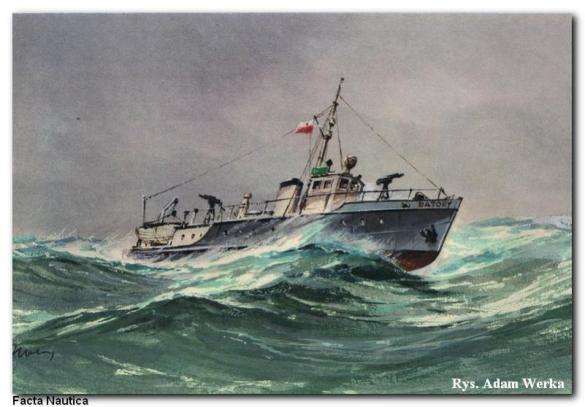

One of the remaining warships in the small flotilla consisted of a small patrol boat of the Border Guard, the ORP Batory. She had been built by the State Engineering Works shipyard in Modlin, launched on 23 April 1932, and entered service with the Border Guard exactly two months later at Hel. Her main task was to suppress smuggling in Gdańsk Bay. She was the biggest and fastest vessel of the Border Guard, classified also as "pursuit cutter" (kuter pościgowy). Prior to the German invasion of Poland, the Batory was mobilized into the Polish Navy, and escaped to Finland, where she would serve as a harbour Patrol Boat based out of Turku for the remainder of WW2. She would return to Poland on 24 October 1945, where she was returned to the Border Defence Army service. She is now in the Polish Navy Museum in Gdynia, where she is going to be restored. She displaced 28 tons, had a length of 28m, was powered by 2 petrol and 1 diesel engine with a speed pf 24.3 knots (45kph) and a range of 245 nautical miles at 11 knots and 145 nautical miles at 24 knots. With a crew of 10, she was armed with 2 machineguns.

Picture sourced from: http://facta-nautica.graptolite.net/sit ... 47x579.jpg

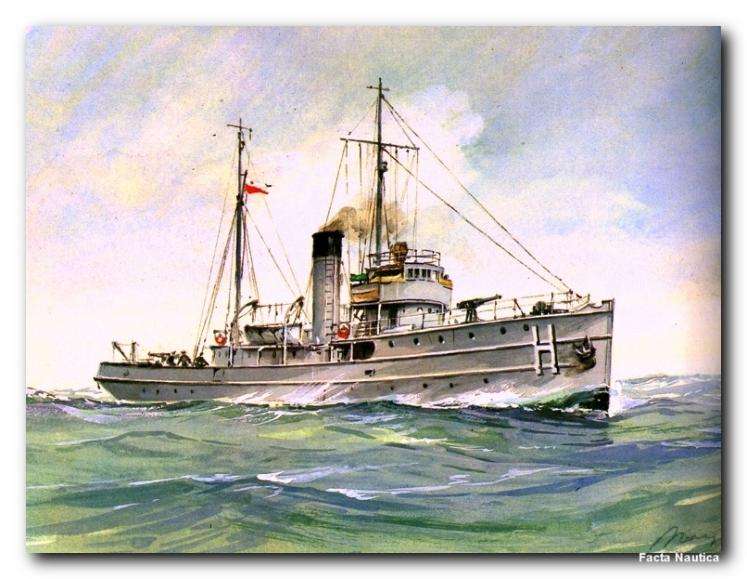

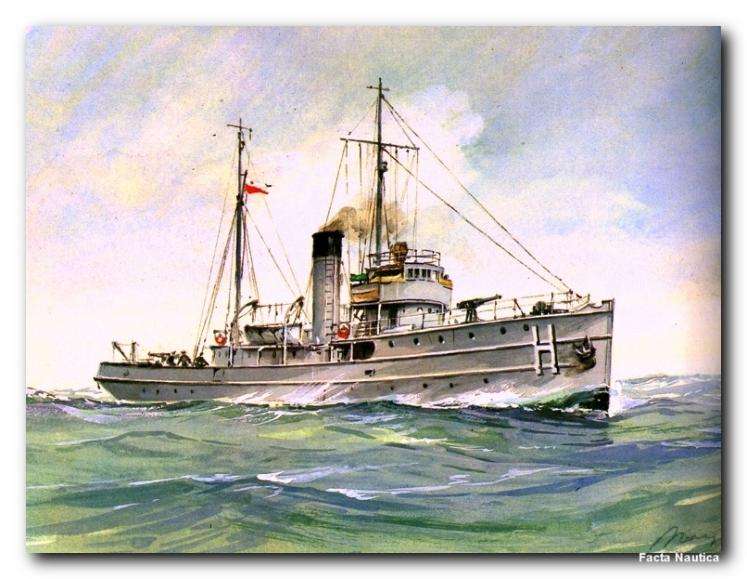

ORP General Haller: The remaining warships of the small flotilla heading towards Finland consisted of two obsolete gunboats, the ORP Generał Haller and ORP Komendant Piłsudski. Both ships were Filin-class guard ships originally built for the Imperial Russian Navy at the Crichton-Vulcan naval yard in Turku, Finland. They were later acquired by the Polish Navy and served as school ships and minelayers. Under the command of Stanisław Mieszkowski, General Haller sucessfully escaped to Finland where she served with the Merivoimat until sunk in action in a Soviet air raid in the last stages of the Winter War. The General Haller displaced 342 tons, was 55m in length with a beam of 7m, had a maximim speed of 14.5 knopts and a crew of 60. Armament consisted of 2 x 76mm guns, 4 machineguns and 30 mines. ORP Komendant Piłsudski also escaped to Finland and was lost in action against the Kreigsmarine when minelaying off the Latvian coast in mid 1944 after Finland declared war on Germany.

Within the Baltic, on 14 September 1939 the Polish submarine ORP Orzeł (Eagle) reached Helsinki and over the next four days a further 3 of the 4 remaining Polish submarines – the Orzel-class sub ORP Sęp (Vulture) and the Wilk-class subs ORP Ryś (Lynx) and ORP Żbik (Wildcat) all arrived at various Finnish ports. Of all the Polish submarines, only the ORP Wilk (Wolf) would escape the Baltic and make it to the UK.

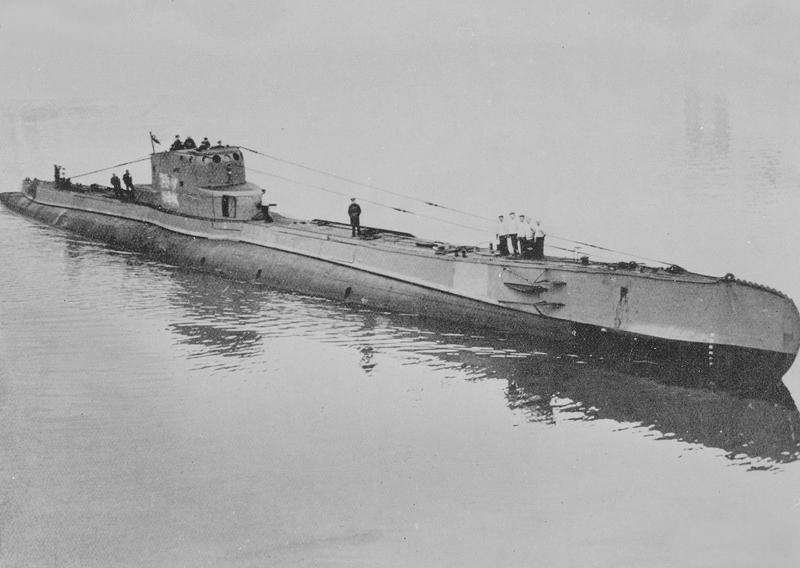

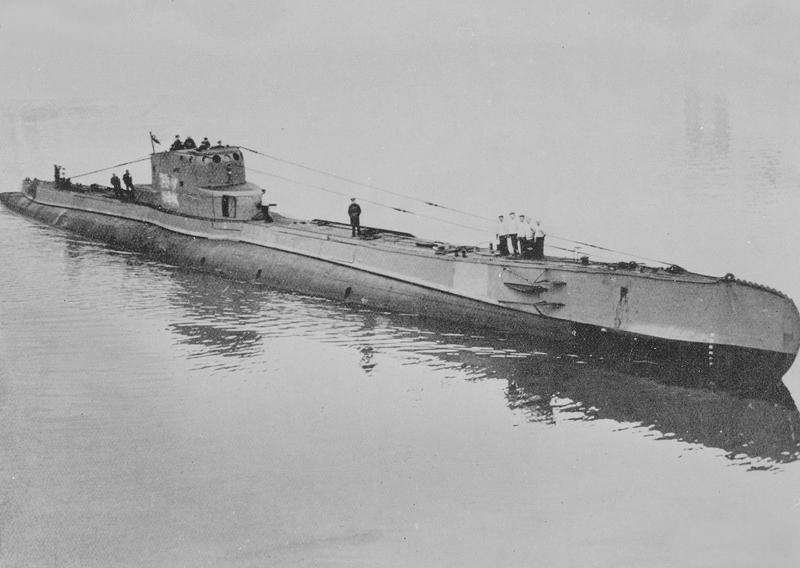

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... _Orzel.jpg

ORP Orzeł was the lead ship of her class of submarines serving in the Polish Navy. Orzeł was laid down 14 August 1936 at the Dutch shipyard of De Schelde; she was launched on 15 January 1938, and commissioned on 2 February 1939. She was a modern design (designed by Polish and Dutch engineers), albeit a bit too large for the shallow Baltic Sea (she displaced 1,473 tons submerged). She had a surface speed of 19.4 knots, a submerged speed of 9 knots and a crew of 60. Armament consisted of 1 x Bofors 105mm gun, 1 x double barrelled Bofors 40mm AA gun, 1 x 13.2mm machinegun and 12 torpedo tubes (4 aft, 4 riudder, 4 waist). She carried 20 torpedoes.

At the start of hostilities Orzeł was on patrol in her designated sector of the Baltic Sea. After expending almost all her torpedoes on attacks on German ships, Orzel was unable to return to the Polish naval bases at Gdynia or Hel. Following orders, the now critically ill Captain of the Orzel ordered the executive officer, Lt.Cdr. Jan Grudzinski, to make for Helsinki. En-route in the Gulf of Finland, she torpedoed a Soviet merchant ship, sparking a major naval incident between the Soviet Navy and the Merivoimat. Following her arrival in Helsinki, both the Germans and the Soviets insisted that the Orzel be interned. Finland refused and instead, “seized” the submarine and granted the crew Finnish citizenship, as they did with all Polish military personnel who arrived in Finland at this time. Both the Soviet Union and Germany expressed outrage. Finland was unmoved.

In service with the Merivoimat as FNS Orzel, she was assigned (with her Polish crew) to the 1st Submarine Flotilla based out of Helsinki and patrolled the Gulf of Finland where sank one, possibly two Soviet submarines as they attempted to break out into the Baltic. In early April 1940, she was part of the Merivoimat submarine task force that was sent south to assist in safeguarding the “Helsinki Convoy.” When the convoy was attacked by a Kreigsmarine flotilla, the FNS Orzel aggressively attacked, launching four torpedoes, two of which hit and sank a Kreigsmarine destroyer. She evaded repeated depth charge attacks and as darkness fell, surfaced and ran head on into the Kreigsmarine flotilla, now returning after taking a beating from the Merivoimat in what would become known as the “Battle of Bornholm.” Orzel managed to launch a further torpedo attack in the darkness and observed a single hit, but was forced to dive before any actual damage could be confirmed.

She returned to Helsinki and on 23 May 1940 departed on her seventh patrol of the Gulf of Finland. No radio signals were received from her after she had sailed, and on 5 June she was ordered to return to base. She never acknowledged reception, and never returned to base. 8 June 1940 was officially accepted as the day of her loss. It was suspected she might have run into a minefield, of which there were many in the Gulf, but the true cause of her loss remains unknown even today. Her remains have never been located.

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... _1939.jpeg

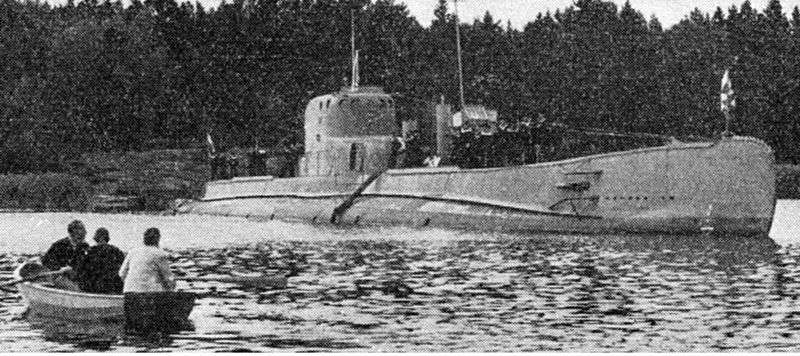

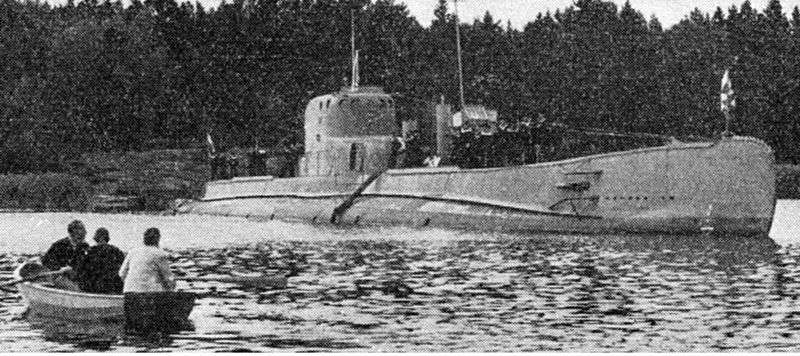

ORP Sep (Vulture) anchored somewhere in the Finnish Archipelago shortly after her arrival, late-Spetember 1939

The second Polish submarine to arrive was also the second Orzel-class submarine in the Polish Navy. ORP Sep (Vulture) was built at the Dutch shipyard Rotterdamse Droogdok Maatschappij, laid down in November 1936 and launched on 17 October 1938. In early 1939 the Polish team supervising the building of the ship noticed a significant slowdown in her construction, which it attributed to the action of German agents. Because of fears that German pressure on Holland would prevent that country from delivering the ship into Polish hands, it was decided to bring the ship to Poland earlier than scheduled. On April 2nd, the ship left for deep water sea trials in Horten, Norway, with a crew of Polish sailors and Dutch technicians, under the Dutch flag. After completing the trials, the Polish crew took control of the ship (against the will of the Dutch technicians on board), raised the Polish flag and left Horten to rendezvous with the Polish destroyer ORP Burza outside the harbour. All but two Dutch workers were left ashore in Norway. From Burza the submarine received additional crew and supplies, then sailed under her escort to Poland. On the way the ship ran out of diesel fuel and had to be taken in tow by the destroyer. On April 18 Sęp arrived in Gdynia, entering the harbour on her electric engines, and was officially commissioned into the Polish Navy. The remaining two Dutch technicians were released and allowed to return home.

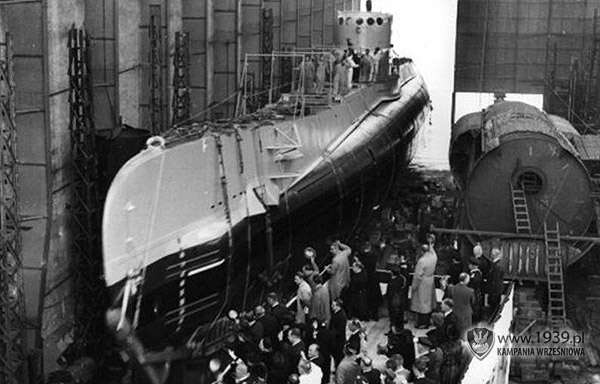

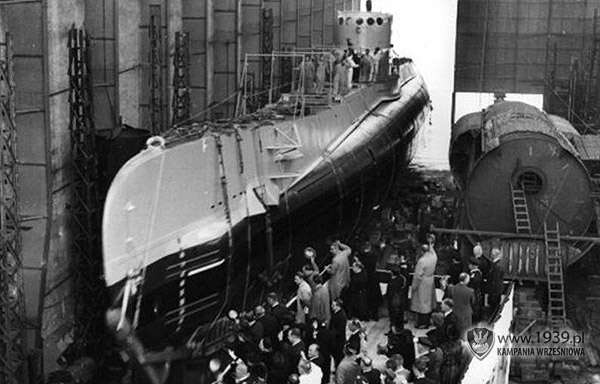

Photo sourced from: http://www.1939.pl/uzbrojenie/polskie/o ... dowa01.jpg

ORP Sep shortly prior to being launched

The fitting out of the ship continued in Poland, with parts arriving from Holland after relations with the Dutch were repaired following the "hijacking." Work was not finished before the war broke out, hence the ship was not at full readiness by September 1939. A visit to Rotterdam to finish the fitting out was contemplated but the outbreak of war prevented this. Sęp sailed into the naval port of Hel a few days before the war started, commanded by Kmdr ppor. Władysław Salamon. On 1st September 1939, the first day of the war, the submarine took up her patrol sector in accordance with the Worek Plan. On 2 September she attacked the German destroyer Friedrich Ihn (Z14) with a single torpedo which missed. The destroyer responded with heavy depth-charging which damaged the submarine, causing water leaks. On 3 September Sęp was attacked again and suffered more damage, which caused more leaks. With her position clearly revealed to the enemy, the submarine left her assigned sector and began to sail in the direction of Gotland Island. Over the next few days she operated without contact with the enemy in the vicinity of Sweden, her crew trying to repair the damage, and her captain requesting permission to return to base in order to carry out more repairs, which was denied.

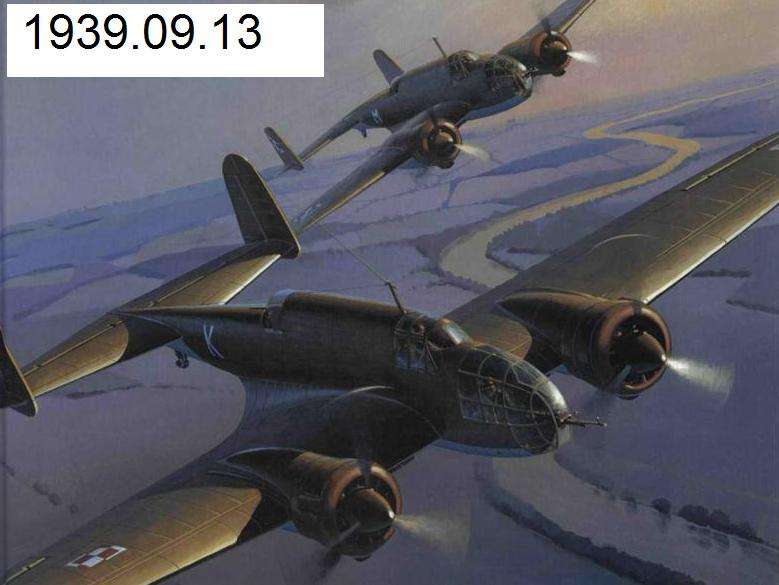

On September 13 the submarine received orders permitting her to sail to England if possible and otherwise to proceed to Finland. The crew at first decided to sail for England but over the next few days the ship's condition deteriorated further with serious leaks when submerged, and the submerging itself taking up to 30 minutes, unacceptably long if the ship was to successfully pass through German patrols on the way to the UK. On September 15 her commander decided to sail for Finland. On September 18 the submarine appeared off Turku and requested permission to enter the harbor. With the political furore over the Orzel still in progress, ORP Sep was discretely moved at night to an offshore island where she was hidden until the fuss had died down, after which she was promptly moved into the Crichton-Vulcan yards and repair work started. Work was completed over the winter and she re-entered service in March 1940. Survi9ving the Winter War, she would be again officially commissioned into the Polish Navy on 1 May 1944, shortly after Finland re-entered WW2 as a belligerent. In a 1959 Polish film the ship was used to portray her twin, ORP Orzeł. In 1959 the submarine became a training ship. She remained the largest submarine of the postwar Polish Navy until 1962. In 1964 she suffered a serious fire (8 crewmembers died), after which she was repaired, but was not fully operational. In 1969 the ship suffered another accident while submerged. The ship was decommissioned on 15 September 1969 and subsequently scrapped in 1972. In 2002 the Polish Navy commissioned the second ORP Sęp, a Kobben class submarine obtained from Norway.

Over the next few days, two of the Wilk-class subs, ORP Ryś (Lynx) and ORP Żbik (Wildcat) would arrive at various Finnish ports. ORP Wilk (Wolf) would leave the Polish coast after deploying her mines and unsuccessfully attacking German shipping, successfully passing the Danish straits (Oresund) on September 14/15, escaping from the Baltic Sea and arriving in Great Britain on September 20. ORP Wilk undertook nine patrols from British bases, without success. The last patrol was between 8 and 20 January 1941, after which the submarine was assigned to training duties. Due to her poor mechanical shape, ORP Wilk was decommissioned as a reserve submarine on April 2, 1942. Because of her poor condition, she was towed to Poland only in October 1952. She was declared unfit to service, decommissioned from the Polish Navy, and scrapped in 1954.

Of the remaining two submarines, ORP Ryś (Lynx) took part in the Worek Plan for the defense of the Polish coast. After suffering battle damage, the submarine withdrew to Finland and was taken into the Merivoimat, along with her crew. After serving through the Winter War on Baltic Patrols from Ahvenanmaa (the Åland Islands), she was officially returned to the Polish Navy on 1 May 1944 where she served until 1955. She was scrapped in 1956. ORP Żbik also took part in the Worek Plan for the defense of the Polish coast. According to the plan she laid her mines, one of which sank the small (525 t) German minesweeper M-85 on 1 October. After suffering battle damage and shortages of fuel, the submarine withdrew to to Finland and was taken into the Merivoimat, along with her crew. After serving through the Winter War on Baltic Patrols from Ahvenanmaa (the Åland Islands), she was officially returned to the Polish Navy on 1 May 1944 where she too served until 1955. As with her sistership, the Ryś, she was scrapped in 1956.

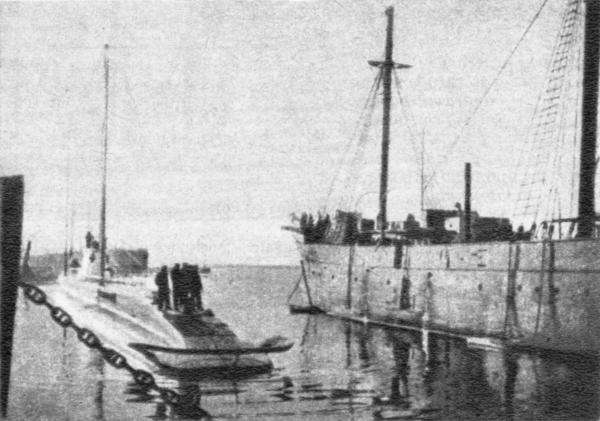

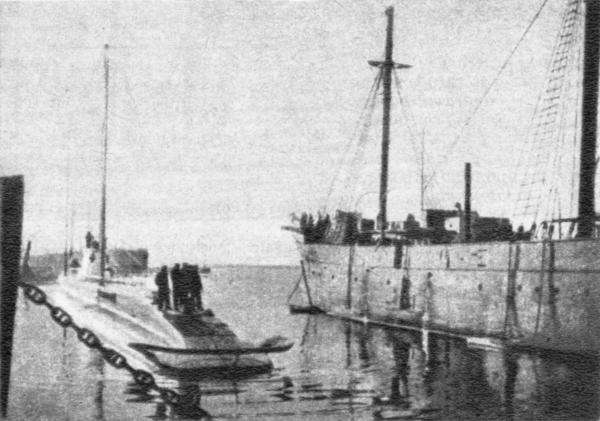

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... P_Lwow.jpg

The Polish submarine ORP Zbik together with the Polish sail training ship Lwow. On the outbreak of WW2, the Zbik was commanded by Lieutenant M. Zebrowski.

Photo sourced from: http://www.weu1918-1939.pl/kmw/podwodne/zbik/zbik_5.jpg

ORP Zbik: The ORP Ryś and ORP Żbik were Wilk class submarines of the Polish Navy, with their design based on that of the French submarine Pierre Chailley, which had been laid down in 1917 and was in service from 1923 to 1936. Wilk, Ryś and Żbik were all laid down in 1927 at Chantiers Augustine Normand shipyard at Le Havre in France. Launched in 1929, they were commissioned into the Polish Navy in 1931 and 1932. The Wilk-class submarines displaced 1,250 tons submerged, were 78.5m long with a beam of 5.9m, had a range of 3,500 nautical miles (4,000 miles), a surface speed pf 14.5 knots and a submerged speed of 9.5 knots. They had a crew of between 46 and 54 and were armed with 1 x 100mm deck gun, 2 x 23.2mm machineguns, 4 bow tubes, 2 rotating midship tubes and carried 16 torpedoes (6 in the tubes and 10 reloads) and 40 mines.

Finland refused demands from the Soviet Union and Germany that these submarines and ships and their crews be turned over to them. Rather than interning the ships and their crews as international law demanded, Finland (again, with the prior agreement of the Polish Government), announced that the ships were being “seized”, re-flagged and integrated into the Finnish Navy, while their crews were granted immediate Finnish citizenhip by special Act of Parliament. As a result, Finland's neutrality was strongly questioned by both the Soviet Union.and Germany over the same period. The protests from both Germany and the Soviet Union were not muted. On the other hand, with Finnish Intelligence knowing what they knew of the secret clauses to the Soviet and German Agreement, Finland simply ignored the protests. Particularly as the 4 Destroyers and 4 Submarines together with the smaller ships were a very useful addition to the Finnish Navy’s strength for a war that the Finnish High Command was almost certain was coming regardless of how Finland acted.

The two Grom-class Destroyers were a known quantity and were excellent destroyers – the Merivoimat had used the design as the basis for their own Destroyers, even calling the class by the same name. The two Wicher-class Destroyers were another story. They were modified versions of the Bourrasque class destroyers built for the French Navy. The Wicher class had severe problems: the destroyers were relatively slow, had a large silhouette with three large funnels, and were inadequately armoured. Additionally, flaws in the design resulted in poorly designed water-resistant chambers and pipelines, which could result in the ship being immobilized after only minor damage. Also the ships suffered from poor stability due to fuel tanks being located high up on the superstructure just below the bridge. Nevertheless, they were destroyers, thay had guns and they could fight. And they would see a great deal of action with the Merivoimat over the course of the Winter War.

Next Post: The escape of remnants of the Polish Air Force to Finland

Zemsta Za Nóż w Plecy - The Polish Volunteers in Finland

In an earlier Post, it was mentioned that in November 1939, there were already two foreign contingents in Finland that had been formed in Finland from Polish soldiers evacuated by the Merivoimat from Lithuania and Latvia in late September and early October after the fall of Poland. The Merivoimat had, in the face of direct opposition from both the USSR and Germany, done what nobody else could have done, and evacuated some 30,000 Poles from Latvia and Lithuania to Finland. In addition, Polish warships, submarines and a number of Polish Airforce aircraft had found safety and refuge in Finland. With the agreement of the Polish Government-in-Exile in London, the warships and aircraft had been incorporated into the Finnish military until such time as they could be transferred to the UK and France to resume the fight.

Arrangements were in progress through October 1939 to have the men themselves shipped out of Finland via Petsamo to the UK, from where they could join the British or French and resume the fight. However, with the rapid escalation of the situation between the USSR and Finland through October and November, events overtook the plans and under the circumstances of the Soviet attack on Finland, the Polish Government-in-Exile agreed that all Poles in Finland who volunteered to fight could stay. Almost to a man, the vast majority of the Poles in Finland had volunteered. The Poles with air force or naval experience were allocated to the Ilmavoimat or Merivoimat as appropriate, while the soldiers were assigned to six Regimental Battle Groups, loosely grouped into two Divisions. These two Divisions would be joined in April 1940 by the Polish Second Infantry Fusiliers Division (15,830 soldiers), shipped in from France and commanded by Brigadier-General Bronisław Prugar-Ketling. In une 1940, after the Allies retreated from Narvik, the Polish Independent Highland Brigade under Zygmunt Bohusz-Szyszko would join the Polish Volunteers in Finland.

Where we have not already done so, we will now look at these units as well as the Polish warships and Polish aircraft that would fight with the Finns against the USSR in the Winter War.

The Polish Navy-in-Exile in Finland

With the fall of Poland to both Germany and the Soviet Union in September 1939, a number of ships and submarines of the Polish Navy had escaped to Finland – something that had quietly been arranged between the two governments earlier in 1939 as a somewhat remote contingency plan that neither country expected to eventuate. The Polish Navy in 1939 was not large. The coastline was relatively short and included no major seaports. In the 1920s and 1930s, such ports were built in Gdynia and Hel, and the Polish Navy was built up under the leadership of Counter-Admiral Józef Unrug (CO of the Fleet) and Vice-Admiral Jerzy Świrski (Chief of Naval Staff), with ships acquired from France, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, and the Navy.

The Naval War Plan was primarily focused on securing Polish supply lines in case of a war against the Soviet Union and it was wih a war with the USSR in mind that most Polish war planning had been carried out. By September 1939 the Polish Navy consisted of 5 submarines, 4 destroyers, and various support vessels and mine-warfare ships. This force was no match for the large German Navy and in the event of war with Germany an alternative strategy of harassment and indirect engagement was planned (the “Peking Plan”). In the case of a war with Germany, the Polish Naval base at Gdynia was clearly likely to be overrun or rendered useless by air attack and the Peking Plan was created in order to remove the Destroyer Division (Dywizjon Kontrtorpedowców) from the immediate operational theatre and needless loss in the event of war with Germany. The Kriegsmarine had a significant numerical advantage over the Polish Navy and the Polish High Command realized that the ships which remained in the small and mostly landlocked Baltic were likely to be quickly sunk by the Germans. Also, the Danish straits were well within operation range of the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe, so there was little chance for the plan to succeed if implemented after hostilities began.

Originally intended to cover the withdrawal of three destroyers of the Polish Navy, the Burza ("Storm"), Błyskawica ("Lightning"), and Grom ("Thunder") to the United Kingdom, this Plan had been amended in early 1939 as a result of negotiations conducted between Marshal Mannerheim, the Polish Prime Minister, Major General Składkowski and the Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Forces, Marshal Edward Smigly-Rydz. While the early version of the Plan had focused on moving the newer Destroyers to the UK, the revisions made following the informal agreement with Finland made provision for the smaller warships and submarines to escape to Finland, something that was within their capabilities, whereas escape from the Baltic entirely was not (with the exception of the submarines). This agreement was undocumented and informal, but the arrangement was that in the event of either country being involved in a war with the USSR, each would assist in whatever way they could and provide a refuge for the others ships, aircraft and soldiers in the event of defeat.

The mounting strain in European politics reached a new tension-point in March 1939, with the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia - first, with the German-inspired secession of Slovakia, and then with the Bohemia "protectorate" enforced upon her at a gun-point. Soon after the "independent" Slovakia also asked to become a German protectorate, and Hitler, at the peak of his diplomatic successes, extorted Klaipeda from Lithuania, and voiced territorial claims in Poland, to which Poland answered with stern refusal. On 18 March 1939, three days after the occupation of Bohemia and Moravia, while German preparations to annexate Klaipeda were under way, the Polish Navy was put on partial alert. The alert concerned primarily the destroyer squadron and the submarine squadron - the only forces of the Polish fleet of considerable combat value, which could be actively engaged in hostilities. Another large Polish warship, the heavy minesweeper Gryf, was kept in reserve. The Polish measures were not entirely unjustified - on 23 March a strong convoy of German ships heading for Klaipeda passed closely along the Polish coast en route from Germany to East Prussia. Under the escort of destroyers and trawlers, the battleship Deutschland carried the Chancellor of the Third Reich himself. After Klaipeda was incorporated into the Reich, the convoy returned along the same route, sparking fears that Hitler, intoxicated with another easy success, would decide to enter Danzig and triumphantly proclaim the return of the city and the whole territory of the Free City of Danzig to Germany. Polish naval ships remained on alert and the Polish outpost on the Westerplatte peninsula in Danzig was also readied to repel any hostile actions of Danzig Nazis. However, this time the German fleet returned to its bases.

In April 1939 political tensions eased and the Polish warships also returned to their bases for maintenance. The submarine squadron was reinforced by a new unit – the submarine Sęp, twin-sister of the Orzeł, had been commissioned in February 1939 amidst an enthusiastic reception following her arrival from the Netherlands. Sęp arrived unfinished, since the Polish command was afraid that on the outbreak of a war she might be trapped. The Poles anticipated that Sęp would return to Rotterdam for further fitting out as soon as the strains in the political situation were eased. Also at this time work on fortifications along the Polish coast and on the Hel peninsula were started. The Polish government opened talks with France and Italy concerning delivery of modern coastal artillery (230mm guns) and also consulted with the Finnish Coastal Defence Forces, whose expertise in this area was well known. As the talks stalled, the Poles approached the British asking them to send a monitor fitted with 381mm guns to the Baltic, but that initiative also failed.

In the summer of 1930, the activities of the Kreigsmarine in the Baltic intensified, as did the volume of merchant shipping between Germany and East Prussia.

The commander of the Polish destroyer Wicher, Captain Stefan de Walden, noted on this occasion:

“At that time our ships conducted round-the-clock duties in turns, during which the task of the ship on duty was to observe the activities of the German ships on the routes leading to East Prussia, as well as estimate, if possible, the type and quantity of the cargo they carried. Needless to say, we also closely observed the movements of the warships, and used to send detailed reports to the Fleet Headquarters immediately after passing the duties to the next ship. In their turn Polish ships, and especially the ship currently on duty, were under close observation of the swastika-marked aircraft, and it used to happen that this or that destroyer or cruiser showed interest in a Polish ship, which could be detected from their manoeuvres and general behaviour.

During such encounters both ships, as a rule, were on alert, having guns and torpedo tubes aimed at the counter-part. Simultaneously they minded respectful distance, which did not require a gun-salute, which could have grave consequences in the circumstances, when both ships aimed at each other. To use a rough naval saying - we were "sniffing" each other. It was an excellent opportunity to train the crews in bearing the elements of a target; a target, which at any time, at any second, might become a real combat target.”

The Polish Navy’s submarines were also kept busy with training and on various exercises preparing them for war, whose inevitability the Navy - due to constant contact with the soon-to-be enemy - was generally expected. While at sea, Polish submarines often found them-selves being used as targets for simulated attacks by German aircraft or submarine chasers – it was no wonder that their crews more often than their colleagues in the surface ships, or in other service branches, had the feeling that open war was just a matter of time.

Captain Włodzimierz Kodrębski thus summarized the atmosphere of those days:

“It rarely happened that ships stayed in ports; switching services to wartime routine ("combat watches"), patrolling and anti-air alert were permanent, and leaves were granted only by day, and only for few hours. Everybody gradually started getting weary of the wartime service conditions, without any satisfaction, since it was forbidden to shoot annoying planes and boats, which followed us everywhere. We were similarly helpless, when we watched Germans sending regular convoys of ships full of troops and war materials to East Prussia. And the real berserk got to all of us one morning, when from the Hel roadstead we saw the German battleship Schleswig-Holstein entering Gdańsk upon the consent of the government of the Republic of Poland, and greeted cheerfully by the hitlerised townfolks.”

Photo sourced from: http://www.militaryfactory.com/ships/im ... lstein.jpg

The German battleship Schleswig-Holstein entering Gdańsk The German battleship was ostensibly on a courtesy visit, but her real task was to take part in the invasion of Poland, according to the Fall Weiß plan. The Germans expected that the war with Poland would be a local conflict, since a Polish-Soviet rapproachment had never taken place and the Western democracies showed no real determination to commit to the Polish cause.

Prior to Poland being attacked by Germany, Mannerheim had, outside the normal government channels, contacted both Składkowski and Smigly-Rydz and informed them that Finland considered the arrangement to include the current situation. Lacking numerical superiority, Polish naval commanders decided in late August to execute the Peking Plan. The Burza ("Storm"), Błyskawica ("Lightning"), and Grom ("Thunder") were ordered to escape the Baltic and make for Lyngenfjiord or Petsamo, while the Wicher (“Gale”) and the heavy minelayer ORP Gryf were ordered to make for Finland in company with the Polish navy’s smaller Minelayers and Minesweepers, the frogman support ship ORP Nurek, the school of naval artillery ship ORP Mazur and two mobilized patrol boats of the Border Guard, the ORP Batory and the ORP Kaszub. The orders came as somewhat of a surprise to the ships Captains and crew - For six months then they had been preparing for the defence of Polish territorial waters, and now they were to abandon them. The Polish Navy’s five submarines were ordered to undertake whatever action against the Kreigsmarine was possible and then proceed to either the UK or Finland at the CO’s discretion.

Initially, Marshal Edward Smigly-Rydz, Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Forces had resisted the implementation of the Peking Plan but he finally agreed., largely due to the plan for a Romanian Bridgehead. It was hoped the Polish forces could hold out in the southeast of the country, near the common border with Romania, until relieved by a Franco-British offensive. Munitions and arms could be delivered from the west via Romanian ports and railways. The Polish Navy outside the Baltic would then be able to assist in escorting the ships delivering military supplies to Romanian ports. As the tensions between Poland and Germany increased, the Commander of the Polish Fleet, Counter Admiral Józef Unrug signed the order for the operation on 26 August 1939, a day after the signing of the Polish-British Common Defence Pact; the order was delivered in sealed envelopes to the ships. On 29 August, the fleet received the signal "Peking, Peking, Peking" from the Polish Commander-in-Chief, Marshall Śmigły-Rydz: "Execute Peking". At 1255 hours, the ships received the signal via signal flags or radio from the signal tower at Oksywie, general quarters were sounded the respective captains of the ships opened the envelopes, and departed at 1415.

The Fleet split into two. The destroyers Błyskawica (commanded by Komandor porucznik Włodzimierz Kodrębski), Burza (commanded by Komandor podporucznik Stanisław Nahorski) and Grom (commanded by Komandor porucznik Włodzimierz Hulewicz) weighed anchor, formed and line and steamed towards Hel at 23 knots, heading for the Baltic exit under the command of Komandor porucznik Roman Stankiewicz. As soon as the squadron made away from the coast and the range of the observation posts, it changed its course again, making towards Bornholm in an attempt to evade German observation. This didn’t work - the German submarine U-31 (Lt.-Cdr. Johannes Habekost) from the squadron detached to trace the movements of the Polish fleet, spotted the Polish destroyers some 30 miles north of Rozewie and - undetected by the Poles - radioed their position to the German command in Swinemunde. Secondly, on the way to Bornholm the Polish destroyers passed a German passenger liner from the Seedienst Ostpreußen transporting German troops to East Prussia. It is not known whether the transport reported the position of the Polish ships, but since the encounter took place in broad daylight, there is little doubt that they were spotted.

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... Peking.jpg

Polish destroyers during execution of the Peking Plan. View from ORP Blyskawica of ORP Grom and ORP Burza / Polskie niszczyciele płynące do Wielkiej Brytanii w ramach planu "Peking" - widok z rufy ORP Błyskawica na ORP Grom i ORP Burza.

As the Polish destroyers approached the Danish straits, another encounter took place close to the Falsterborev lightship, this time with unidentified warships steaming from the straits southward. Although the Polish commanders agreed that these might be Danish ships (a gunboat and a torpedo boat), the ships were blacked out, which aroused understandable concern and called for caution. The outbreak of the war was expected momentarily, a potential enemy could turn into a real one any time, and torpedoe tubes on the Polish destroyers were kept ready in case of any attack. Nevertheless, the two squadrons passed each other and disappeared in the darkness. It was not until many years later that it became known that the ships the Polish squadron encountered on that night of 30/31 August 1939 were actually the Kreigsmarine cruisers Köln and Königsberg with an escort of destroyers. What is more, the Germans knew whom they had encountered, while the Poles were left to more or less guess that the encountered squadron might be German, although they were not able to identify them positively.

The Polish warships passed the Falsterborev and around midnight entered the Øresund, full of shallows and banks, forcing a reduction in speed to 16 knots. It was the most difficult stage of the voyage, since the Poles were forced by the Danish regulations regarding foreign warships steaming in Danish territorial waters to take the more difficult of the sea routes through the Sund: the Flintrinne passage. Soon after, when only a few miles away from the Skagen lighthouse, the Polish squadron was spotted by German aircraft which followed until nightfall, when the Poles turned towards the Norwegian coast, and from there headed out into the North Sea. In the evening of 31 August the Polish squadron was also spotted from the German submarine U-19. The German conduct was correct and without any provocative action as there still was no state of war between Germany and Poland.

The small squadron changed course towards Norway in order to shake off the pursuit during the night. The ships entered the North Sea, and at 0925 on the morning of 1 September learned about the German invasion of Poland. At 1258 that day, they encountered the Merivoimat destroyer FNS Jylhä which had been sent south from Lyngenfjiord to meet them. Each of the three destroyers received a Merivoimat liaison officer together with Merivoimat signals personnel and were reflagged under the Merivoimat Naval Ensign. The crews were immediately sworn in as Finnish Citizens (with a special dispensation as per the Act of the Parliament passed on 1 Sepetember 1939, permitting dual Polish-Finnish citizenship for members of the Polish military). Two days later, at 17:37 on 3 September 1930, they dropped anchor in Lyngenfjord. Thoughtfully, the first deliveries to the three ex-Polish destroyers were complete sets of Merivoimat dinnerware for the Officers Messes.

Merivoimat dinnerware - plate

Merivoimat dinnerware – plate backstamp – manufactured by the Arabia Porcelain Factory

Photo sourced from: http://www.polishgreatness.com/sitebuil ... 72x269.jpg

The Polish Destroyer ORP Blyskawica anchored in Lyngenfjiord harbour – October 1939. ORP Blyskawica was commanded by Lt. Cmdr. Włodzimierz Kodrębski.

Photo sourced from http://img.audiovis.nac.gov.pl/PIC/PIC_1-W-2090-1.jpg

Photo from August 1935: Wizyta niemieckiego krążownika "Konigsberg" w Polsce: Przedstawiciele załogi krążownika "Konigsberg" oraz witający ich wojskowi przed samolotem na lotnisku Okęcie. Widoczni m.in. komandor Hubert Schmundt (4 z lewej), niemiecki attache wojskowy gen. Max Schindler (2 z lewej), komandor Kodrębski (1 z prawej) / Visit of the German cruiser "Konigsberg" to Poland: Representatives of the crew of the cruiser "Konigsberg" being welcomed. Visible among others are Captain Hubert Schmundt (4th left), the German military attache, General Max Schindler (2nd left), Commander Kodrębski, Polish Navy (1st, right)

Photo sourced from: http://www.polishgreatness.com/sitebuil ... 18x319.jpg

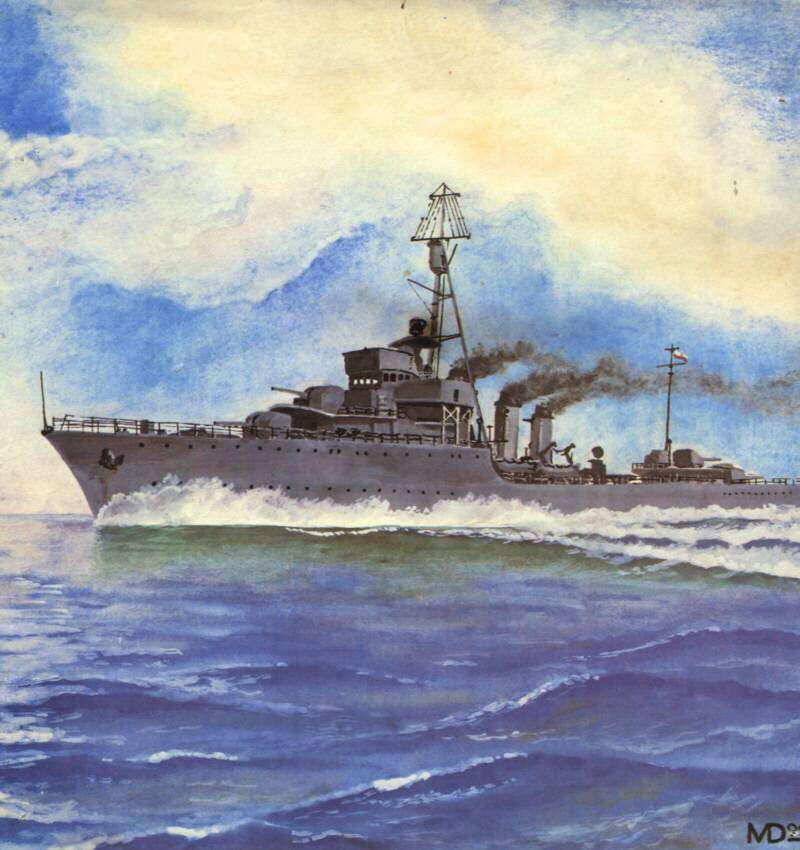

The Polish Destroyers ORP Blyskawica and ORP Grom tied up together in Lyngenfjiord. ORP Grom was commanded by Komandor porucznik Włodzimierz Hulewicz. The Polish Navy’s Grom-class destroyers built by the British company of J. Samuel White, Cowes.They were laid down in 1935 and commissioned in 1937. The two Groms were some of the fastest and most heavily-armed pre-World War II destroyers. Despite having ordered its previous pair of destroyers (ORP Burza and ORP Wicher) from France, a country with which it had strong ties, Poland decided to acquire the second pair from the United Kingdom, possibly in recognition of the excellence of British destroyer designs at the time. The selected design resulted in large and powerful ships, superior to German and Soviet destroyers of the time, and comparable to the famous British Tribal class of 1936. The main armament was changed from the 130 mm used on the Wicher-class destroyer to the standard British destroyer calibre of 4.7 inch (120 mm). However, the guns were not British, but rather the Swedish Bofors 50cal QF M34/36, the same as those used previously on the minelayer ORP Gryf.

As was mentioned in an earlier Post on the Merivoimat, Finland had licensed the design for the Grom-class destroyers from the Polish Government even before construction of the Polish orders had started, an arrangement that suited both parties, although the Finnish Navy modified the design somewhat, reducing the number of 120mm guns and substantially increasing the anti-aircraft armament. The Finnish Navy Grom-class destroyers Jylhä and Jyry were commissioned in 1936 and 1937 respectively. Jymy and Jyske were delivered in mid-1938, Vasama and Vinha in mid-1939 and Viima and Vihuri in late 1939. A further 6 destroyers of this class would be constructed following the end of the Winter War and prior to Finland’s re-entry into WW2 in early 1944.

Photo sourced from: http://www.computerage.co.uk/navy/pic/burza.jpg

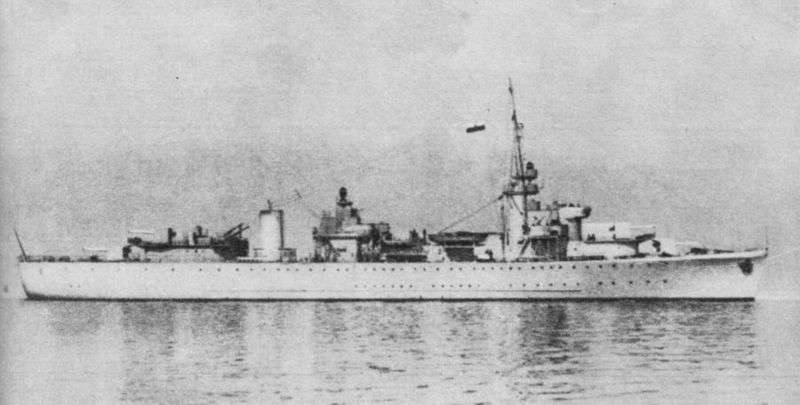

The Polish Navy’s Wicher-class destroyer ORP Burza (Storm), commanded by Komandor podporucznik Stanisław Nahorski, en route to Lyngenfjiord: ORP Burza and her sister ship, ORP Wicher, were ordered on 2 April 1926 from the French shipyard Chantiers Naval Francais. She entered service in 1932 (roughly 4 years after the scheduled delivery date), and her first commander became Kmdr Bolesław Sokołowski. On 30 August 1939 the Polish Navy’s destroyers and submarines were ordered to execute the “Peking Plan”, and headed for Lyngenfjiord or Finland as their orders indicated. Burza fought with the Merivoimat against the Soviet Navy in late 1939. In April 1940 she was part of the Helsinki Convoy Escort as the Convoy entered the Baltic. She saw action againts the Kreigsmarine and then served as part of an FNS Baltic Convoy Escort Group for the remainder of the Winter War. After the Winter War, Burza became a Merivoimat Training Ship and then in 1944 she was transferred back to the Polish Navy and became a submarine tender for Polish submarines. At the end of WW2 she returned to Gdynia where she was later overhauled, remaining in serviced until 1955. In 1960, she became a museum ship. After Błyskawica replaced her in that role, she was scrapped in 1977.

Photo sourced from: http://img.audiovis.nac.gov.pl/PIC/PIC_1-W-353.jpg

Komandor podporucznik (Lieutenant Commander) Stanisław Nahorski, Captain of ORP Burza.

The remainder of the Fleet, led by the destroyer Wicher and under the overall command of Wicher’s CO, Stefan de Walden, steamed for Finland on the same day, with the minelayers hastily deploying their final loads of mines to augment the minefields already laid. Accompanying the Wicher were the heavy minelayer ORP Gryf commanded by Stefan Kwiatkowski, the six small ships of the Minelayer/Minesweeper Flotilla (Flotylla Minowców), composed mostly of the so-called birdies (ptaszki, a nickname coined after the fact that all of the Jaskółka class ships were named after a different species of bird), the frogman support ship ORP Nurek, the school of naval artillery ship ORP Mazur, a small patrol boat of the Border Guard, the ORP Batory and two obsolete gunboats, the ORP Generał Haller and ORP Komendant Piłsudski. It was a sizable little flotilla and at the maximum speed of the slowest ship,

Photo sourced from: http://www.biurodabrowski.republika.pl/wicher.jpg

ORP Wicher at speed in the Baltic Sea, 30 August 1939: ORP Wicher was commissioned into the Polish Navy on 8 July 1930 and was the first modern ship of the Polish Navy. During the Interbellum, Wicher served a variety of roles, mostly political. For instance, on 15 June 1932, she was sent to the port of the Free City of Danzig (Gdańsk) to meet two British destroyers entering the port and to underline the Polish political influence in that city. In March 1931 she sailed to Madeira, from where she brought the Marshal of Poland Józef Piłsudski and his family back to Poland. She also visited Stockholm in August 1932, Leningrad in July 1934, Kiel in June 1935 and Helsinki and Tallinn the following month.

Photo sourced from: http://aj-press.home.pl/images/rekl/eow28_s_85.jpg

ORP Wicher and her sister ship ORP Burza side by side at Tallinn (Estonia) harbour during the goodwill visit of July 1935.

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... finder.JPG

Range-finder of the Polish destroyer ORP Wicher. Photo from 1931. Wicher could reach a maximum speed of 33.8 knots, had a crew of 162 and was armed with four 130 mm Schneider-Creusot Model 1924 guns (4xI), two 40 mm Vickers - Armstrong AA guns (2xI), four torpedo tubes 550/533 mm (2xII), two depth charge launchers, two Thornycroft depth charge throwers and 60 mines. By the late 1930s it was apparent that the armament was insufficient. The French guns had a low rate of fire and the ship had inadequate protection against aerial bombardment. To partially solve the problem, in the autumn of 1935 two additional double 13.2 mm Hotchkiss heavy machine guns were added.

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... P_Gryf.jpg

The heavy minelayer ORP Gryf (Griffin), commanded by Stefan Kwiatkowski. Laid down in 1934 at the French shipyard Chantiers et Ateliers A. Normand in Le Havre, she was launched in 1936. Built to Polish specifications, she was intended as a large minelayer with an armament close to that of a destroyer. Powered by two Sulzer 8SD48 engines of 6,000 horsepower (4,500 kW) each, she was capable of 20 knots (37 km/h/23 mph), fast for her size. She also had a remarkably long range of roughly 9,500 nautical miles (17,600 km) at 14 knots (26 km/h). As the Polish Navy was small and no other state expressed a need for such a vessel, she remained the only ship of the class. Whiler her usual complement of crew was 162, she also served as a school ship and could take on board up to 60 additional students. Her armament consisted of 6 × 120 mm (4.7 in) Bofors wz. 34/36 guns (2 × 2 and 2 × 1) in four turrets, 4 × 40 mm (1.6 in) Bofors wz. 36 AA guns (2 × 2), 4 × 13.2 mm (0.52 in) Hotchkiss wz. 30 HMG's (2 × 2) and 8 × naval mine racks, with up to 600 mines. With her heavy load of mines, she would prove a remarkably useful addition to the Merivoimat in the Winter War.

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... taszki.jpg

The Polish minesweepers OORP Rybitwa, Czajka, Mewa, Jaskółka in 1937 The six small ships of the Minelayer/Minesweeper Flotilla (Flotylla Minowców) were of the Jaskółka class, built during the 1930's. They were the first sea going warships to be built in Poland and were of a versatile design allowing the ships to serve in the role of either a minesweeper, small minelayer or a sub chaser. All were named after birds, therefore the class was nicknamed: ptaszki (birdies) in Polish. The first 4 ships of the class were built at Gdynia in the Modlin shipyard. After they entered service they proved to be a good design so a further 2 were ordered in the mid 30s. They had a maximum speed of 17.5 knots, displaced 183 toms, had a crew of 30, were powered by 2 shaft diesel engines, 1040 BHP with a length of 45m and a beam of 5.5m. They were armed with 1 x 75mm or 76mm, 2 x 7.92mm machineguns and could carry 20 mines or depth charges.

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... el_bok.jpg

A model of ORP Jaskółka in the Pomorskim Muzeum Wojskowym. Jaskółka was under the command of Captain Tadeusz Borysiewicz. Of the other warships in this class, ORP Żuraw was under the command of Capt Mjr. Robert Kasperski, ORP Rybitwa was under the command of Lieutenant Commander Kazimierz Miładowski. The CO’s of Mewa, Czajka and Czapla are not recorded.

Photo sourced from: http://forum.valka.cz/files/orp_nurek_2_509.jpg

Photo sourced from: http://www.computerage.co.uk/navy/pic/jaskolka.jpg

ORP Jaskółka in action with the Merivoimat, Gulf of Finland, Summer 1940

The Polish Navy’s diver support ship ORP Nurek, a small ship, displacing only 110 tons and with a length of 26.5m and a beam of 5.8m. Her maximum speed was 10 knots. In the early 1930's the Navy with decided to build a modern ship to support naval divers, who made do with an old and battered support boat (a British M-52, purchased from surplus, which has been given the name "Nurek" (Diver) in 1922). After long deliberation, a design from engineer A. Potyrała was accepted. In the second half of 1935 construction started at the naval shipyard in Gdynia. This was an indication of the development of this yard, only a few years earlier, all orders received had of necessity, to be completed in the Gdansk Shipyard. In July 1936 the ship was completed. By order of the Minister of Defense she was named ORP "Diver". Her entry into service took place on 1 November 1936. The ship was equipped with a decompression chamber of Polish construction, a diving pump, winch and radio. Her commander was Warrant Officer W. Tomasiewicz. Until the outbreak of war and the execution of the Peking Plan, the ship served as a base for underwater work and training of Polish Navy divers.

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... /Mazur.jpg