MSZ

Banned

Okay, this is my first attempt at writing a timeline. I always liked the idea of no WW2 and thought about various scenarios which could avert it. The POD in this one is Adolf Hitler being killed by Maurice Bavaud after annexing the Sudetenland, leading to Goring taking power in Germany and a Cold War between the capitalists, communists and fascist taking place instead of a world war. For those who would like to point out that OTL the Reich was indebted so much that it would have to go bankrupt soon after 1938 without a war – assume the PoD being also Goring being overall a more clever guy, doing a better job running the first 4 year plan. Dictatorships tend to pay their debts, even if they have to kill their own people. So just please handwave it, okay?

Historians still debate on the question which event could be considered as marking the beginning of the Cold War. While some point towards the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 in Russia as the point where “traditional” competition between world Great Powers turned into an ideological - rather than a national - conflict, others consider it the Fascist takeover of Italy in 1922, pointing out that it was only after the birth of Fascism that the actual three ideologies competing for global dominance in the XXth century were born. The National Socialist Revolution of 1933 in Germany is considered another one, as it was the German Reich that led Fascism into becoming an actual alternative to both the Capitalist and Communist ideologies, competing with the states following them for power and influence

It was a strange coincidence that both Vladimir Lenin, as well as Adolf Hitler, the two men who “begun” the Cold War, by starting their respective revolutions in their countries, have not seen it develop beyond it’s infant stages. Having suffered a stroke in 1922, Lenin died in 1924, leaving a vacuum of power which his fellow Bolsheviks would come to fight to fill. Joseph Stalin succeeded, quickly becoming the undisputed ruler of the Soviet Union. A paranoiac on his own, like many of his comrades, believing the Soviet Union to be the carrier of an inevitable Global Soviet Revolution, Stalin’s policies allowed the broken country to rise from the ashes of the Great War and the Revolutionary War back to Great Power status, albeit at a terrible cost in human life.

Adolf Hitler’s demise in 1938 also occurred before the clash between National Socialism and Communism he predicted had come. On November 9, during the celebrations of the 15th anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch, the chancellor was killed by Maurice Bavaud, shot two times in the chest. Despite immediate medical aid, “the Fuhrer” died on the streets of Munich, in the very cradle of the Nazi Revolution which he started and led to victory. Becoming another martyr of the movement, the popularity of National Socialists soared, at the same time reducing the leftover opposition into irrelevance – the accusations that it was the “reds and reactionaries” who killed the man who returned the Reich to greatness denied anyone who disagreed with the new order any place in politics or public office, as they were immediately branded as anti-German and anti-state, either arrested or outright executed.

And just like the Lenin’s, his death too would bring the Nazi’s into a conflict of succession. Having officially been holding only the office of “Führer und Reichskanzler” after taking over presidency powers in 1934 and without the office of Vice Chancellor being occupied, his legal successor was uncertain. The main competitors soon became Rudolf Hess, the Deputy Fuhrer and the Chairman of the NSDAP; and Hermann Goring, the Head of the Luftwaffe and President of the Reichstag, among other of his held offices.

The two sided conflict would come to reflect a general split in the Nazi party, between the so-called “Blood and Soil”, “Agrarian” wing - led by Hess, followers of Hitler's vision of an endless Social Darwinist struggle between different races – and the “Wilhelmine Imperialists” – led by Goring, who viewed themselves as the successors of Imperial Germany, Nazism being the modern incarnation of the traditional German Sonderweg. While the NSDAP would also be filled with various opportunists, who hopped on the bandwagon of the Nazi movement during it’s rise after the Great Depression, actual believers were still plenty, and remained loyal to the party leadership.

Rudolf Hess and the “B&S” wing appeared to have the initial upper hand – holding not only a large part of the country’s administration via it’s Gaue but also enjoying popular support among the population - thanks to the charisma of Hess, as well as the efforts of Goebbels, the Minister of Propaganda. With Himmler and his Schutzstaffel, at his disposal as well as the Gestapo and other police forces on his side, the matter of the Deputy Fuhrer stepping into the office of Chancellor seemed obvious.

Goring would however have allies of his own, and was not willing for the matter of succession to simply take it’s course. Wilhelm Frick, the German minister of internal affairs, would prove to be one of his greatest assets, passing a regulation on declaring a three-month long period of national mourning after “the Fuhrer’s” death. For that time Goring, acting as President of the Reichstag, prevented it from assembling and electing Hitler’s successor. The three month period during which the casket of “the Fuhrer” traveled across Germany for all people to see, starting and ending in Munich, his final resting place, would be a time in which the Wilhelmine faction gathered it’s strength to challenge Hess, Himmler and Goebbels.

Memorial srvices for Adolf Hitler being held in Munich

Goring was quick to regain control over large portions of the German police forces, by having the office of Chef der Deutschen Polizei – held by Himmler – to be directly responsible before the minister of interior, rather than the Chancellor, due to it’s vacancy. While Himmler did object to it, he found himself powerless to prevent the ordinary police to fall to Goring. With a great many of policeman despising the SS, most of local police units of the Ordnungspolizei begun to report directly to the Minister of Interior, going around the Reichsfuhrer. Those who remained loyal to Himmler were dismissed. With the prosecutors offices subordinated to Franz Gurtner, another ally of Goring, the Wilhelmine faction gained control over the entire judicial branch of government. The “B&S” faction found its power significantly reduced, with the SS becoming its main will-enforcement unit.

Goring’s actions allowed him to bypass the limitations put in place by the Ministry of Propaganda, led by Goebbels. With a large part of German media tycoons being uncertain of their future should the German News Office grow in power, many of them saw Goring as a safer alternative. Mostly free from the threat of arrest, German media would come to hugely support Goring, praising him as the “right hand” of the deceased Chancellor, as well as cover the matter of the investigation regarding his death. Many supporters of Hess found themselves under accusations of either being part of the anti-Hitler conspiracy, or their negligence allowing the assassination to take place, strongly affecting the publics view of them. Goring’s “blessing” of immunity would also extend to other of his supporters within the German Big Business, as his position of being in charge of the 4 years plan gave him great influence over the German economy, bringing industrial tycoons to his side.

But Goring’s main source of strength would come not from the police or large business owners, but from the Army. While the Wehrmacht was nominally placed outside the matter of politics, many high ranking officers were opposed not only to the “B&S” wing, disliking the Volkish policies it represented as well as the SS, mostly due to the conservative, even aristocratic background of the military, but were also terrified of the concept of a future war – something that the “Agrarians” were seemingly pursuing. Goring’s own military background helped him to gain support of the OKW. In January 1939, a secret deal was made between the Wilhelmine Imperialists and the Army, in which Wilhelm Keitel and other top ranking officers pledged to support Goring in case of the “B&S” getting into power.

The deal would not remain a secret long though, and soon the word reached Hess and Himmler. Realizing that the possibility of a second “Night of Long Knives” – a move which terminated the third “socialist” wing of the NSDAP – was becoming more and more possible, the group decided that compromising with Goring was a safer move. Before the first assembly of the Reichstag after Hitler’s demise, an agreement was reached in Berchtesgaden between the parties. In it’s accordance, Goring was to obtain the office of Chancellor; Rudolf Hess was to become the President of the Reich; Joseph Goebbels to become the Chairman of the NSDAP. The trio would also split the various ministries, Gaue and other offices between their supporters, in a bid of “sharing” power.

Joseph Goebbels, Hermann Göring and Rudolf Hess, the triumvirate ruling Germany after the death of Adolf Hitler

Why Goring allowed for such a compromise is uncertain – the SS was hardly a force the Police and the Army could not overcome. However, removing his competitors from the German political scene was not something Goring could do either – he did not have the prestige to simply oust them and usurp power, much less to terminate them. Doing so could easily lead to popular dissent growing too strong for him too handle. He also did fear the reaction of the German military in case of martial law being introduced and it having to be used in restoring order in the streets – while the high ranking officers might have supported him, the matter would ultimately be decided by the grunts, many of whom, having sworn their loyalty to the Fuhrer as well as having a “rural” background. It was feared that they could ultimately side with the “agrarian” faction at least in some parts of Germany. A civil war was what positively terrified Goring – both because it could shatter Germany completely, as well as that it would de facto allow the military to take power over – Goring knowing that he was being viewed as a lesser evil, not a perfect option for many of the Old Guard conservatives in the armed forces.

On February 1st 1939, the Reichstag session in the Kroll Opera House in Berlin took place, officially confirming the provisions of the Berchtesgaden agreement. After 3 minutes of silence in memory of the deceased Fuhrer, the delegates unanimously voted in both Rudolf Hess as Reichsprazident and Hermann Goring as Reichskanzler. The next day during the Party rally in Munich Hess stepped down from the position of Party Chairman, and the delegates elected Joseph Goebbels in his place.

The transition of power was complete, and with only little blood being spilled – much unlike the previous 1932 events, as well as the Soviet Union. That Goring managed to obtain power despite the adversities was in a large part possible thanks to the rather sluggish nature of Hess’s character – his publicity being not used as well as it could, and mostly acting only in response to Goring’s doings, hardly ever trying to disrupt his plans. While Goebbels persona and rhetorical talents were of great advantage in bolstering their ranks, they also led to a lot of Germans throwing their support to Goring – as his uncompromising nature and aggressiveness and what was sometimes called ‘lunacy’ deterred people from the “agrarians”. The SS and Gestapo, while successfully being able in imprisoning, and occasionally eliminating opponents in “mysterious circumstances”, also found themselves targets of the state police and prosecutors, hampering the effectiveness of their actions.

Hermann Göring as chancellor of the German Reich

The new arrangements would still leave Goring with his power being somewhat restricted – with Hess holding presidential powers, it was still possible for him to be dismissed by the President, as well as any new laws presented by the Chancellor had to have his nominal acceptance. With the Reichstag still being divided into factions, and Goebbels and the NSDAP watching over his conduct, the Berchtesgaden agreement came to be more akin to a ceasefire than a peace, with both sides trying to get the necessary edge over the other.

Goring’s policy of weakening Goebbels came mostly from re-empowering the various local governments of the former Landers and their administrative units – who were to be responsible before the central government, rather than the Chairman of the NSDAP. By 1936, the local governments had lost nearly all power to their Nazi counterparts or were controlled by persons who held both government and Nazi titles alike. This led to the continued existence of German titles such as Bürgermeister, as well as the existence of German state legislatures but without any real power to speak of. Goring strongly emphasized splitting the Party and State offices, thus limiting Goebbels control and strengthening his own. He did not however return to the federal structure of pre-nazi Germany and eventually came to officially abolish the Landers, granting their powers to the Gaue, with the Gauleiters becoming appointed and dismissed by the Chancellor only.

Goring would also come to weaken Hess by keeping him isolated from actual state affairs, while allowing him to bask in the prestige of being the Head of State – sending him on useless foreign voyages as well as public meetings with Party officials and other meetings or rallies. Goring would mostly ignore the necessity of Hess’s acceptance for new legislation by simply ignoring him – and Hess having no institution to appeal to deny them legitimacy. Hess wasn’t very ambitious and did not seek too get involved in internal conflicts for power – his position of Reichsprezident making him absolutely content, much to the dismay of other, more ambitious people than him.

But weakening his opponents wasn’t enough – in order to not only preserve, but also strengthen his position, Goring needed success and fame, both in internal as well as foreign affairs. As the chief of the 4-year plan, Goring knew of the dire need for additional funds to be obtained if the Third Reich was to avoid bankruptcy, as well as economic reforms having to be implemented. Doing so would however mean drawing unavoidable criticism – and threaten his position. In order for changes to successfully occur, Goring would have to resort both to short term solutions, as well as gaining support from successes in foreign policy to gain the popular support necessary for longer-term reforms.

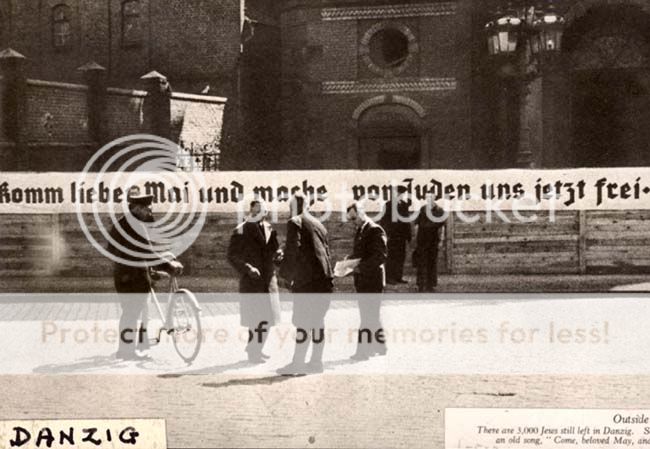

A pan-germanist like Hitler, Goring honestly did believe in the “Ein Volk – Ein Reich” principle – that every state ought to be a homogenous nation-state for that nation, encompassing all peoples of that nationality. In an attempt to gain additional funds, Goring began a campaign of stripping “non-Germans” from their property, the seized assets benefiting the budget of the Reich. The Jews were an obvious first choice, although they weren’t the only ones to suffer that fate – the various peoples of the Sudetenland also had their wealth taken away, and forced into emigration, as did “politically uncertain” individuals all over the country. Pogroms became weekly occurrences with synagogues being looted to the core, going so far as having bells stolen and smelted for precious metals. Financial assets and estates of businessmen who were previously tied to other political forces were taken away as well. Even those who sought to hide their wealth by cashing out and placing their money in foreign banks did not have it so easy, as Nazi authorities responsible for financial oversight would efficiently find out those who attempted it, reported them to the police, leading to either them or their families being arrested – and only let go after paying a very large bail.

In foreign matters, the principle of “national self determination” became the standing doctrine of fascist Germany. Since the Treaty of Versailles has led to a large German diaspora being left in almost every state neighboring Germany, and that most of the new states in central Europe have declared their independence on that basis, the demand for the same right being granted to the Germans came to a convenient way of demanding changes to the Versaillesdiktat. Both the Anschluss and the Munich agreement were both examples of this policy being enforced – the goal being the foundation of a true pan-German state.

This policy and rhetoric however brought concerns in the states surrounding Germany – as all of them were potential targets of territorial demands. Following the Munich conference both France and the UK have started military build-ups, aimed at preventing further German revisionism. Their public opinion opposed another war however – leaving London’s and Paris’s capacity at stopping Germany limited. Their publics were also somewhat accepting towards the Germans demands on the basis of their right of self-determination being respected, opposing only the way that right was enforced – by military strength and blackmails.

Goring realized that by accepting certain procedural principles the western democracies considered pivotal, he could gain a fairly free hand in dealing with his eastern neighbors. In order to gain more acceptance from the west, Goring was quick to “legitimize” Munich by holding a referendum in that province. The referendum was held on April 10 1939, one year after the Anschluss referendum, which asked German voters to approve of a single Nazi-party list for the new 814 member German Reichstag. Asking “Do you approve of the reunification of Sudetenland with the German Reich accomplished on 10 October 1938”, despite elections to the Reichstag having took place in the province already in December, the vote gave a 99.3 % turnout with 99.4% voting in favor.

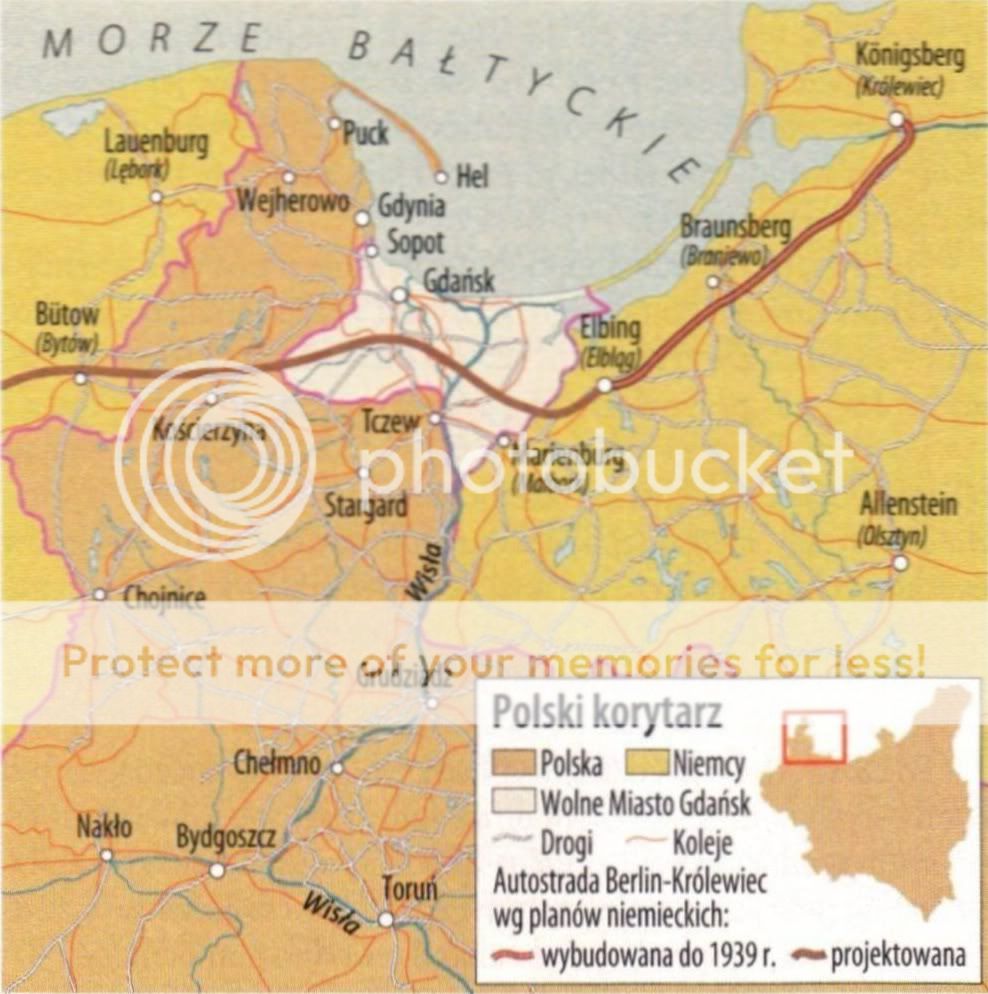

With that accomplished, Goring moved onto his first victim – Lithuania. The region of Memelland was occupied by Lithuania in the "Klaipėda Revolt" of 1923 and subsequently annexed. Memel Territory was recognized as an part of the Republic of Lithuania by Germany on 29 January 1928, when the two countries signed the Lithuanian-German Border Treaty. However, the region remained predominantly German, it’s inhabitants following a pro-German policy. Soon after the Sudetenland referendum, Nazi-sponsored demonstrations began, demanding that the Memellanders be allowed to decide their state belonging as well.

Goring’s pressure on Lithuania remained surprisingly weak in the early weeks of the crisis, he himself restricting himself to calm speeches, and the German foreign ministry to declarations of goodwill, and hope of a peaceful resolution of the arising conflict. Knowing well how isolated Lithuania was, and that should the need for the use of force come it would remain available, Goring turned west, looking for acceptance for his move among the western democracies. Having difficulties denying the Germans in Lithuania their rights, as well as having little interest in the region, the UK gave unclear messages. Pointing out the promise of Adolf Hitler that after Munich, Germany would not seek any other territorial gains, London sought mostly to preserve it’s image of a Great Power, one which does not simply remain inactive in continental affairs, and even if does remain inactive, it does so for a reason – not because of a general lack of agenda. Allowing both the English and French to make up their minds, Goring waited for a suitable response which did come sooner that he expected - on June 3 in a meeting in Paris regarding negotiations of the planned Franco-German Declaration of Friendship, the French minister of foreign affairs Georges Bonnet, suggested that any future border revision in Europe should only occur after plebiscites in that area have been held, and only under League of Nations supervision. This was exactly what Joachim von Ribbentrop was waiting for, the information being quickly published in both German and French press on Monday the 5th. With this consent being granted, Goring moved on to Lithuania, demanding that a plebiscite overseen by the LoN and German authorities to take place in Memelland. With both the French and British public either being irrelevant on the matter, or even accepting German “reasonable” demands, Lithuania found no allies to protect it – despite Germany not having presented a threat of using force to have it’s way. With the League eventually coming to an agreement, in which it accepted the formation of a commission to “inspect” the situation of Germans in Memelland – a commission to which not only Lithuanians, but also Latvians and Estonians were not allowed to join – Lithuania officially refused the demands, not accepting to allow the commission to operate. A massive protest against this move was held in Klaipeda, which ended violently, one woman being killed from police gunfire. This was the final straw that led to the German Ultimatum of June 15th, where Goring informed that German troops would secure the area within 48 hours from it’s presentation to the Lithuanian President, using force if Lithuania resisted. With no other options, Anastas Smetona agreed to withdraw from Memelland, and on the 16 of June, the province was under German control.

German troops entering the city of Memel

The occupation of Memelland proceeded peacefully, with not one shot being fired. Local German militias managed to occupy the bridges on the river Memel even before Wehrmacht troops arrived, overseeing the Lithuanian armies withdrawal. Local police forces were suspended from duty, and the control of the area was granted to Gauleiter Richard Walther Darré – who replaced Erich Koch earlier, per the Berchtesgaden agreement. Staying true to his demands, Goring declared that the plebiscite on the future of Memelland would take place on Monday 19th of June and invited LoN delegates to oversee it. With very little time being granted, the League managed to send just a few people who oversaw only the voting booths in the city of Klaipeda and a few other urban areas. Much like expected, the plebiscite had a positive turnout for Germany, with over 90% of the population voting in favor of unification with Germany. The province was subsequently incorporated to the Gaue of East Prussia.

The events of June 1939 were mostly accepted by the world – foreign observers pointing out the “benevolent” way of Goring, who used mostly democratic procedures to achieve results, as opposed to Hitler’s action in Ostmark and the Sudetenland – where force and blackmail were the only tools in use. While accusations of the plebiscite being rigged were present form the beginning, even those accusers could not deny that the will of reunifications was shared by the great majority of the regions population – and could not be changed. The relative lack of opposition from the western states, particularly France had also come to be a great enlightenment for the German Foreign Affairs Ministry – as it had realized that the French Republic would not act against Germany without obtaining British guarantees first. France, already being surrounded by Fascist state from the north-west, south-west and south (since Franco’s victory in the Spanish Civil War) should not have allowed for the principle of self-determination to be successfully used in favor of Germany, as not only had it strengthened Germany – something France feared most of all – but also could easily be used against France itself, as the province of Elsass-Lotharingen held a German plurality. The lack of French reaction brought Goring to come to believe that French and British interests did not completely overlap – the gap between them being that particular space where Germany could push the French out, without risking condemnation and trouble from the United Kingdom. Thus obtaining British consent – whether genuine, silent or a grudging acceptance - would become the main goal of Germany’s foreign policy in the east, as having it would automatically be followed by French acceptance, or at least non-action. With central Europe being an area where the UK never had particular interest in, Goring sought out to test just how far were the British willing to accept German growth in influence and power in that region.

Historians still debate on the question which event could be considered as marking the beginning of the Cold War. While some point towards the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 in Russia as the point where “traditional” competition between world Great Powers turned into an ideological - rather than a national - conflict, others consider it the Fascist takeover of Italy in 1922, pointing out that it was only after the birth of Fascism that the actual three ideologies competing for global dominance in the XXth century were born. The National Socialist Revolution of 1933 in Germany is considered another one, as it was the German Reich that led Fascism into becoming an actual alternative to both the Capitalist and Communist ideologies, competing with the states following them for power and influence

It was a strange coincidence that both Vladimir Lenin, as well as Adolf Hitler, the two men who “begun” the Cold War, by starting their respective revolutions in their countries, have not seen it develop beyond it’s infant stages. Having suffered a stroke in 1922, Lenin died in 1924, leaving a vacuum of power which his fellow Bolsheviks would come to fight to fill. Joseph Stalin succeeded, quickly becoming the undisputed ruler of the Soviet Union. A paranoiac on his own, like many of his comrades, believing the Soviet Union to be the carrier of an inevitable Global Soviet Revolution, Stalin’s policies allowed the broken country to rise from the ashes of the Great War and the Revolutionary War back to Great Power status, albeit at a terrible cost in human life.

Adolf Hitler’s demise in 1938 also occurred before the clash between National Socialism and Communism he predicted had come. On November 9, during the celebrations of the 15th anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch, the chancellor was killed by Maurice Bavaud, shot two times in the chest. Despite immediate medical aid, “the Fuhrer” died on the streets of Munich, in the very cradle of the Nazi Revolution which he started and led to victory. Becoming another martyr of the movement, the popularity of National Socialists soared, at the same time reducing the leftover opposition into irrelevance – the accusations that it was the “reds and reactionaries” who killed the man who returned the Reich to greatness denied anyone who disagreed with the new order any place in politics or public office, as they were immediately branded as anti-German and anti-state, either arrested or outright executed.

And just like the Lenin’s, his death too would bring the Nazi’s into a conflict of succession. Having officially been holding only the office of “Führer und Reichskanzler” after taking over presidency powers in 1934 and without the office of Vice Chancellor being occupied, his legal successor was uncertain. The main competitors soon became Rudolf Hess, the Deputy Fuhrer and the Chairman of the NSDAP; and Hermann Goring, the Head of the Luftwaffe and President of the Reichstag, among other of his held offices.

The two sided conflict would come to reflect a general split in the Nazi party, between the so-called “Blood and Soil”, “Agrarian” wing - led by Hess, followers of Hitler's vision of an endless Social Darwinist struggle between different races – and the “Wilhelmine Imperialists” – led by Goring, who viewed themselves as the successors of Imperial Germany, Nazism being the modern incarnation of the traditional German Sonderweg. While the NSDAP would also be filled with various opportunists, who hopped on the bandwagon of the Nazi movement during it’s rise after the Great Depression, actual believers were still plenty, and remained loyal to the party leadership.

Rudolf Hess and the “B&S” wing appeared to have the initial upper hand – holding not only a large part of the country’s administration via it’s Gaue but also enjoying popular support among the population - thanks to the charisma of Hess, as well as the efforts of Goebbels, the Minister of Propaganda. With Himmler and his Schutzstaffel, at his disposal as well as the Gestapo and other police forces on his side, the matter of the Deputy Fuhrer stepping into the office of Chancellor seemed obvious.

Goring would however have allies of his own, and was not willing for the matter of succession to simply take it’s course. Wilhelm Frick, the German minister of internal affairs, would prove to be one of his greatest assets, passing a regulation on declaring a three-month long period of national mourning after “the Fuhrer’s” death. For that time Goring, acting as President of the Reichstag, prevented it from assembling and electing Hitler’s successor. The three month period during which the casket of “the Fuhrer” traveled across Germany for all people to see, starting and ending in Munich, his final resting place, would be a time in which the Wilhelmine faction gathered it’s strength to challenge Hess, Himmler and Goebbels.

Memorial srvices for Adolf Hitler being held in Munich

Goring was quick to regain control over large portions of the German police forces, by having the office of Chef der Deutschen Polizei – held by Himmler – to be directly responsible before the minister of interior, rather than the Chancellor, due to it’s vacancy. While Himmler did object to it, he found himself powerless to prevent the ordinary police to fall to Goring. With a great many of policeman despising the SS, most of local police units of the Ordnungspolizei begun to report directly to the Minister of Interior, going around the Reichsfuhrer. Those who remained loyal to Himmler were dismissed. With the prosecutors offices subordinated to Franz Gurtner, another ally of Goring, the Wilhelmine faction gained control over the entire judicial branch of government. The “B&S” faction found its power significantly reduced, with the SS becoming its main will-enforcement unit.

Goring’s actions allowed him to bypass the limitations put in place by the Ministry of Propaganda, led by Goebbels. With a large part of German media tycoons being uncertain of their future should the German News Office grow in power, many of them saw Goring as a safer alternative. Mostly free from the threat of arrest, German media would come to hugely support Goring, praising him as the “right hand” of the deceased Chancellor, as well as cover the matter of the investigation regarding his death. Many supporters of Hess found themselves under accusations of either being part of the anti-Hitler conspiracy, or their negligence allowing the assassination to take place, strongly affecting the publics view of them. Goring’s “blessing” of immunity would also extend to other of his supporters within the German Big Business, as his position of being in charge of the 4 years plan gave him great influence over the German economy, bringing industrial tycoons to his side.

But Goring’s main source of strength would come not from the police or large business owners, but from the Army. While the Wehrmacht was nominally placed outside the matter of politics, many high ranking officers were opposed not only to the “B&S” wing, disliking the Volkish policies it represented as well as the SS, mostly due to the conservative, even aristocratic background of the military, but were also terrified of the concept of a future war – something that the “Agrarians” were seemingly pursuing. Goring’s own military background helped him to gain support of the OKW. In January 1939, a secret deal was made between the Wilhelmine Imperialists and the Army, in which Wilhelm Keitel and other top ranking officers pledged to support Goring in case of the “B&S” getting into power.

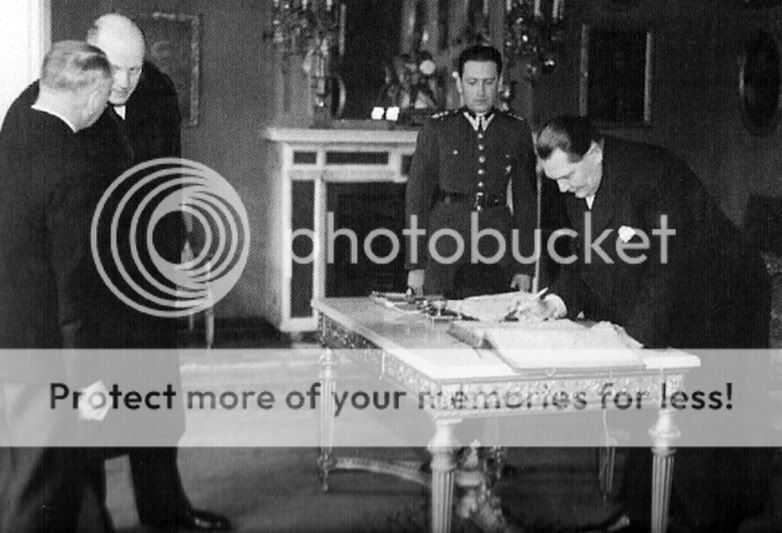

The deal would not remain a secret long though, and soon the word reached Hess and Himmler. Realizing that the possibility of a second “Night of Long Knives” – a move which terminated the third “socialist” wing of the NSDAP – was becoming more and more possible, the group decided that compromising with Goring was a safer move. Before the first assembly of the Reichstag after Hitler’s demise, an agreement was reached in Berchtesgaden between the parties. In it’s accordance, Goring was to obtain the office of Chancellor; Rudolf Hess was to become the President of the Reich; Joseph Goebbels to become the Chairman of the NSDAP. The trio would also split the various ministries, Gaue and other offices between their supporters, in a bid of “sharing” power.

Joseph Goebbels, Hermann Göring and Rudolf Hess, the triumvirate ruling Germany after the death of Adolf Hitler

Why Goring allowed for such a compromise is uncertain – the SS was hardly a force the Police and the Army could not overcome. However, removing his competitors from the German political scene was not something Goring could do either – he did not have the prestige to simply oust them and usurp power, much less to terminate them. Doing so could easily lead to popular dissent growing too strong for him too handle. He also did fear the reaction of the German military in case of martial law being introduced and it having to be used in restoring order in the streets – while the high ranking officers might have supported him, the matter would ultimately be decided by the grunts, many of whom, having sworn their loyalty to the Fuhrer as well as having a “rural” background. It was feared that they could ultimately side with the “agrarian” faction at least in some parts of Germany. A civil war was what positively terrified Goring – both because it could shatter Germany completely, as well as that it would de facto allow the military to take power over – Goring knowing that he was being viewed as a lesser evil, not a perfect option for many of the Old Guard conservatives in the armed forces.

On February 1st 1939, the Reichstag session in the Kroll Opera House in Berlin took place, officially confirming the provisions of the Berchtesgaden agreement. After 3 minutes of silence in memory of the deceased Fuhrer, the delegates unanimously voted in both Rudolf Hess as Reichsprazident and Hermann Goring as Reichskanzler. The next day during the Party rally in Munich Hess stepped down from the position of Party Chairman, and the delegates elected Joseph Goebbels in his place.

The transition of power was complete, and with only little blood being spilled – much unlike the previous 1932 events, as well as the Soviet Union. That Goring managed to obtain power despite the adversities was in a large part possible thanks to the rather sluggish nature of Hess’s character – his publicity being not used as well as it could, and mostly acting only in response to Goring’s doings, hardly ever trying to disrupt his plans. While Goebbels persona and rhetorical talents were of great advantage in bolstering their ranks, they also led to a lot of Germans throwing their support to Goring – as his uncompromising nature and aggressiveness and what was sometimes called ‘lunacy’ deterred people from the “agrarians”. The SS and Gestapo, while successfully being able in imprisoning, and occasionally eliminating opponents in “mysterious circumstances”, also found themselves targets of the state police and prosecutors, hampering the effectiveness of their actions.

Hermann Göring as chancellor of the German Reich

The new arrangements would still leave Goring with his power being somewhat restricted – with Hess holding presidential powers, it was still possible for him to be dismissed by the President, as well as any new laws presented by the Chancellor had to have his nominal acceptance. With the Reichstag still being divided into factions, and Goebbels and the NSDAP watching over his conduct, the Berchtesgaden agreement came to be more akin to a ceasefire than a peace, with both sides trying to get the necessary edge over the other.

Goring’s policy of weakening Goebbels came mostly from re-empowering the various local governments of the former Landers and their administrative units – who were to be responsible before the central government, rather than the Chairman of the NSDAP. By 1936, the local governments had lost nearly all power to their Nazi counterparts or were controlled by persons who held both government and Nazi titles alike. This led to the continued existence of German titles such as Bürgermeister, as well as the existence of German state legislatures but without any real power to speak of. Goring strongly emphasized splitting the Party and State offices, thus limiting Goebbels control and strengthening his own. He did not however return to the federal structure of pre-nazi Germany and eventually came to officially abolish the Landers, granting their powers to the Gaue, with the Gauleiters becoming appointed and dismissed by the Chancellor only.

Goring would also come to weaken Hess by keeping him isolated from actual state affairs, while allowing him to bask in the prestige of being the Head of State – sending him on useless foreign voyages as well as public meetings with Party officials and other meetings or rallies. Goring would mostly ignore the necessity of Hess’s acceptance for new legislation by simply ignoring him – and Hess having no institution to appeal to deny them legitimacy. Hess wasn’t very ambitious and did not seek too get involved in internal conflicts for power – his position of Reichsprezident making him absolutely content, much to the dismay of other, more ambitious people than him.

But weakening his opponents wasn’t enough – in order to not only preserve, but also strengthen his position, Goring needed success and fame, both in internal as well as foreign affairs. As the chief of the 4-year plan, Goring knew of the dire need for additional funds to be obtained if the Third Reich was to avoid bankruptcy, as well as economic reforms having to be implemented. Doing so would however mean drawing unavoidable criticism – and threaten his position. In order for changes to successfully occur, Goring would have to resort both to short term solutions, as well as gaining support from successes in foreign policy to gain the popular support necessary for longer-term reforms.

A pan-germanist like Hitler, Goring honestly did believe in the “Ein Volk – Ein Reich” principle – that every state ought to be a homogenous nation-state for that nation, encompassing all peoples of that nationality. In an attempt to gain additional funds, Goring began a campaign of stripping “non-Germans” from their property, the seized assets benefiting the budget of the Reich. The Jews were an obvious first choice, although they weren’t the only ones to suffer that fate – the various peoples of the Sudetenland also had their wealth taken away, and forced into emigration, as did “politically uncertain” individuals all over the country. Pogroms became weekly occurrences with synagogues being looted to the core, going so far as having bells stolen and smelted for precious metals. Financial assets and estates of businessmen who were previously tied to other political forces were taken away as well. Even those who sought to hide their wealth by cashing out and placing their money in foreign banks did not have it so easy, as Nazi authorities responsible for financial oversight would efficiently find out those who attempted it, reported them to the police, leading to either them or their families being arrested – and only let go after paying a very large bail.

In foreign matters, the principle of “national self determination” became the standing doctrine of fascist Germany. Since the Treaty of Versailles has led to a large German diaspora being left in almost every state neighboring Germany, and that most of the new states in central Europe have declared their independence on that basis, the demand for the same right being granted to the Germans came to a convenient way of demanding changes to the Versaillesdiktat. Both the Anschluss and the Munich agreement were both examples of this policy being enforced – the goal being the foundation of a true pan-German state.

This policy and rhetoric however brought concerns in the states surrounding Germany – as all of them were potential targets of territorial demands. Following the Munich conference both France and the UK have started military build-ups, aimed at preventing further German revisionism. Their public opinion opposed another war however – leaving London’s and Paris’s capacity at stopping Germany limited. Their publics were also somewhat accepting towards the Germans demands on the basis of their right of self-determination being respected, opposing only the way that right was enforced – by military strength and blackmails.

Goring realized that by accepting certain procedural principles the western democracies considered pivotal, he could gain a fairly free hand in dealing with his eastern neighbors. In order to gain more acceptance from the west, Goring was quick to “legitimize” Munich by holding a referendum in that province. The referendum was held on April 10 1939, one year after the Anschluss referendum, which asked German voters to approve of a single Nazi-party list for the new 814 member German Reichstag. Asking “Do you approve of the reunification of Sudetenland with the German Reich accomplished on 10 October 1938”, despite elections to the Reichstag having took place in the province already in December, the vote gave a 99.3 % turnout with 99.4% voting in favor.

With that accomplished, Goring moved onto his first victim – Lithuania. The region of Memelland was occupied by Lithuania in the "Klaipėda Revolt" of 1923 and subsequently annexed. Memel Territory was recognized as an part of the Republic of Lithuania by Germany on 29 January 1928, when the two countries signed the Lithuanian-German Border Treaty. However, the region remained predominantly German, it’s inhabitants following a pro-German policy. Soon after the Sudetenland referendum, Nazi-sponsored demonstrations began, demanding that the Memellanders be allowed to decide their state belonging as well.

Goring’s pressure on Lithuania remained surprisingly weak in the early weeks of the crisis, he himself restricting himself to calm speeches, and the German foreign ministry to declarations of goodwill, and hope of a peaceful resolution of the arising conflict. Knowing well how isolated Lithuania was, and that should the need for the use of force come it would remain available, Goring turned west, looking for acceptance for his move among the western democracies. Having difficulties denying the Germans in Lithuania their rights, as well as having little interest in the region, the UK gave unclear messages. Pointing out the promise of Adolf Hitler that after Munich, Germany would not seek any other territorial gains, London sought mostly to preserve it’s image of a Great Power, one which does not simply remain inactive in continental affairs, and even if does remain inactive, it does so for a reason – not because of a general lack of agenda. Allowing both the English and French to make up their minds, Goring waited for a suitable response which did come sooner that he expected - on June 3 in a meeting in Paris regarding negotiations of the planned Franco-German Declaration of Friendship, the French minister of foreign affairs Georges Bonnet, suggested that any future border revision in Europe should only occur after plebiscites in that area have been held, and only under League of Nations supervision. This was exactly what Joachim von Ribbentrop was waiting for, the information being quickly published in both German and French press on Monday the 5th. With this consent being granted, Goring moved on to Lithuania, demanding that a plebiscite overseen by the LoN and German authorities to take place in Memelland. With both the French and British public either being irrelevant on the matter, or even accepting German “reasonable” demands, Lithuania found no allies to protect it – despite Germany not having presented a threat of using force to have it’s way. With the League eventually coming to an agreement, in which it accepted the formation of a commission to “inspect” the situation of Germans in Memelland – a commission to which not only Lithuanians, but also Latvians and Estonians were not allowed to join – Lithuania officially refused the demands, not accepting to allow the commission to operate. A massive protest against this move was held in Klaipeda, which ended violently, one woman being killed from police gunfire. This was the final straw that led to the German Ultimatum of June 15th, where Goring informed that German troops would secure the area within 48 hours from it’s presentation to the Lithuanian President, using force if Lithuania resisted. With no other options, Anastas Smetona agreed to withdraw from Memelland, and on the 16 of June, the province was under German control.

German troops entering the city of Memel

The occupation of Memelland proceeded peacefully, with not one shot being fired. Local German militias managed to occupy the bridges on the river Memel even before Wehrmacht troops arrived, overseeing the Lithuanian armies withdrawal. Local police forces were suspended from duty, and the control of the area was granted to Gauleiter Richard Walther Darré – who replaced Erich Koch earlier, per the Berchtesgaden agreement. Staying true to his demands, Goring declared that the plebiscite on the future of Memelland would take place on Monday 19th of June and invited LoN delegates to oversee it. With very little time being granted, the League managed to send just a few people who oversaw only the voting booths in the city of Klaipeda and a few other urban areas. Much like expected, the plebiscite had a positive turnout for Germany, with over 90% of the population voting in favor of unification with Germany. The province was subsequently incorporated to the Gaue of East Prussia.

The events of June 1939 were mostly accepted by the world – foreign observers pointing out the “benevolent” way of Goring, who used mostly democratic procedures to achieve results, as opposed to Hitler’s action in Ostmark and the Sudetenland – where force and blackmail were the only tools in use. While accusations of the plebiscite being rigged were present form the beginning, even those accusers could not deny that the will of reunifications was shared by the great majority of the regions population – and could not be changed. The relative lack of opposition from the western states, particularly France had also come to be a great enlightenment for the German Foreign Affairs Ministry – as it had realized that the French Republic would not act against Germany without obtaining British guarantees first. France, already being surrounded by Fascist state from the north-west, south-west and south (since Franco’s victory in the Spanish Civil War) should not have allowed for the principle of self-determination to be successfully used in favor of Germany, as not only had it strengthened Germany – something France feared most of all – but also could easily be used against France itself, as the province of Elsass-Lotharingen held a German plurality. The lack of French reaction brought Goring to come to believe that French and British interests did not completely overlap – the gap between them being that particular space where Germany could push the French out, without risking condemnation and trouble from the United Kingdom. Thus obtaining British consent – whether genuine, silent or a grudging acceptance - would become the main goal of Germany’s foreign policy in the east, as having it would automatically be followed by French acceptance, or at least non-action. With central Europe being an area where the UK never had particular interest in, Goring sought out to test just how far were the British willing to accept German growth in influence and power in that region.

Last edited: