Chapter 4

Katholicism on the Kongo

After the frustrations with the Baka, Charles and the remaining monks sailed south in search for the settlements of the Kongo peoples. Their search came to a conclusion after nearly two weeks when they reached the mouth of the massive Kongo River and encountered settlements along the river banks.

This time the language barrier was not an issue as the monks had brought a Baka guide along with them, John Koozime. Koozime was one of the few Baka who had converted to Catholicism and was relativley fluent in the languages of the Kongo. Compelled by his new faith, a possible place in history, a desire to see the world, and pressed on by Charles he became the monks guide.

Without the awkward phase of the language barrier, the monks were able to adapt much more readily to Kongo society than with the Akan or Baka. Knowledge of Kongo customs learned from the Baka and the Kongo traders also gave the monks an edge. Because of these factors and the experiences from before the monks finally had the success they were looking for. Unlike with the Akan or the Baka, a good number of Kongo converted initially and several had considerable zeal to go with their conversion. Before long, Charles was able to arrange with the chiefs of the Kongo tribes the building of an organized settlement around a new abbey.

It was in this way that in mid-1166 the settlement of St. Victor was created around the original wooden framework of St. Victor’s Abbey (named for Pope Saint Victor I, the first African pope). It was around the construction of St. Victor’s Abbey that Charles came to meet a prominent chief, Nwene Mbata.

Historians question whether Mbata was truly religious or if he was motivated to befriend the Europeans for technological and political gain. Regardless, Mbata quickly converted, becoming the first chief to take up the new religion. Mbata’s conversion compelled many Kongo to convert as well and by 1167 the tribe could largely be considered the first real Christian peoples of sub-Saharan Africa not located in Ethiopia.

Mbata’s conversion did more than bring many Africans to Christianity; it solidified his friendship with Charles. We do know that Mbata was an enthusiastic scholar and cunning politician. Charles and him talked for hours about the history of Europe and the church, the political structures of the nations there. They even delved into economics, trade, and occasionally even weaponry.

In 1168 Mbata began encouraging the construction of crude European style weapons. The Kongo crossbow entered the Kongo’s arsenal around this time and writings from one of the monks depicts a crude catapult, though this was probably simply for show rather than for practicality. As Mbata’s power grew, so did his influence over the Kongo people. Mbata was successful in uniting several of the Kongo tribes under his rule and even struck deals with some lesser chiefs allowing them some autonomy in exchange for his supremacy in the first glimpses of Kongoese feudalism.

By 1169 it was clearly obvious that Mbata was using Catholicism as an excuse for expansion of his power. Charles and the monks certainly knew this but turned the other way. Besides they had come to bring Catholicism to Africa, something Mbata was spreading. The church was thriving under his rule, St. Victor’s Abbey had been rebuilt in stone and several other abbeys and churches had been erected as well. Even the rough communications with St. Peter’s Abbey amongst the Baka showed that the Baka were converting more rapidly as the stories of Kongo power increased. Though the Baka were still far behind the rapid progress being shown in the lands of the Kongo.

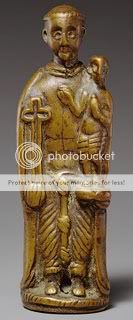

Picture of St. Peter's Cathedral, 1879

The way Mbata spread his power and influence over the other Kongo tribes is an amazing political strategy still studied to this day. Mbata became a champion of this new faith and began pushing Catholicism as the religion of the future and the foundation for progress and social climbing. As the

de facto secular leader of the religion (Charles was still very much in command of the spiritual leadership), Mbata began to create a new stratification in Kongo society that polarized families and villages. Many older Kongo refused to convert so easily but many younger Kongo people, and the most skilled warriors and shrewd leaders, flocked to the religion and the opportunity it presented to climb society’s ladder very fast and very soon. When necessary Mbata would use his newfound leadership and leverage to promote allies and bring them closer, or ostracize enemies from society and overcome the obstacles they imposed; oftentimes without bloodshed. Whenever Mbata and his movement encountered trouble from a prominent family or counter movement questioning his motives and leadership, and bloodless political maneuvering didn’t work, he always had the benefit of his skilled warrior class equipped with better technology and tactics. Granted those weapons and tactics would have led Mbata to a slaughter on a European battlefield they were so crude, but the new ideas revolutionized tribal warfare in the region. Mbata was also quiet shrewd on the battlefield, no slouch as a warrior himself, he was able to create himself as a great fighter and battlefield hero. He never led an offensive and instead when warfare seemed to be inevitable he pushed and prodded his enemies to the point that they would attack him and he would crush them on the defensive. This way he managed to paint himself not as a conqueror, but as a peacemaker simply defending his people and his honor. He also had a penchant for leaving the occasional great warrior, or leader that wasn’t to “misguided” alive and in his debt.

After one larger battle between his forces and the forces of a countermovement in which Mbata’s warriors defeated and captured nearly 200 warriors and their chief, Mbata had the enemy chief brought to him. Before both groups of warriors Mbata gave the man a choice, that Mbata’s forces would either kill the leader and spare his warriors or the warriors would all be killed and the leader would be spared, with the choice lying in the chief’s hands. Knowing he was ruined and deciding to go out with honor, the chief told Mbata to kill him. The chief was ordered to kneel before Mbata, presumably to be beheaded, but instead Mbata informed him that he so admired his self sacrifice and courage before death that he could not kill so worthy an adversary. He offered the chief a chance to be reborn anew in the glory of God and to fight side by side with Mbata as his brother in Christ. The chief quickly accepted this radical turn of events and was baptized on the spot by Charles. So powerful was the moment and the message that the 200 captured warriors clamored for baptisms and service as well. The chief would become a close Mbata family ally and would be knighted several years in the future. All of this transpired even though we know today from documents and other evidence that Mbata was planning this from the start. If the chief had asked for his life before his warriors then Mbata planned to execute him and use the power of that image to bring the betrayed 200 warriors into the Mbata fold!

But while Mbata expanded his power and reputation across the Kongo lands and was easily the most powerful Kongoese person, he still did not have the legal control he desired over his people. One aspect of European culture Mbata was fascinated with was royalty and the concept of empire. Mbata was a greatly ambitious person from his remarkably early rise as chief of his village to his perfect playing of the spiritual and secular politics of the arrival of Catholicism. He saw no reason why the peoples of the Kongo could not be united under the twin behemoths of his house and the church. If he could establish a Kongo state with himself at the helm, his legacy would forever be cemented in history and the future of his house would be secure.

By 1171 Mbata had largely solidified his control, whether

de facto or

de jure over the majority of the Kongo lands. The only thing that stood between him and his goal was an alliance of dissatisfied chieftains and some outside non-Kongoese clans worried about the suddenly very real possibility of a powerful and radicaly new Christian Kongo state. Built up in the south and centered on the mountain stronghold of Mbanza Kongo, if Mbata and his allies could defeat them, he would have control over the Kongo.

In late 1172, the warriors assembled to depose Mbata began heading to St. Victor. Their goal was to kill Mbata, his sons, daughters, and wives, and burn the Catholic abbey to the ground with any Europeans they found inside. In a literal battle with everything on the line, Mbata and his warriors prepared defenses outside the village of Coinzo.

The numbers of the two armies is generally considered to be almost even, perhaps with a slight nod in favor of those against Mbata thanks to non-Kongoese forces participating. Mbata’s forces though were equipped with the crude European weapons. Crude pikes, swords, various types of bows, and a good number of shields would give the Mbata warriors an edge over the enemy equipped with a smattering of captured quality weapons but for the most part still using spears and tightly woven armor and thatch shields. We don’t know much about the battle of Coinzo outside of the fact that Mbata prevailed, his tactics and weapons winning out over the enemy. From Coinzo Mbata and his warriors pushed on to Mbanza Kongo where they stormed the mountain and executed the chief of the town. It should be noted that the storming of Mbanza Kongo occurred at night and also coincided with a meteor shower, an event the citizens of Mbanza Kongo and those warriors fighting there took as a miracle and the inspiration for Mbata’s coat of arms and banner; a red cross wreathed in golden flames of faith.

Several days after the battle Mbata declared himself the Mwene Kongo, or Lord of the Kongo (for readability purposes Mwene Kongo is henceforth referred to simply as King). Mbata made the centralized and easily defensible stronghold of Mbanza Kongo his capital and erected the grand St. Thomas Cathedral (named so because Mbata’s favorite saint was Thomas, whom had traveled away from the European world) to be the seat of Catholic power in Africa.

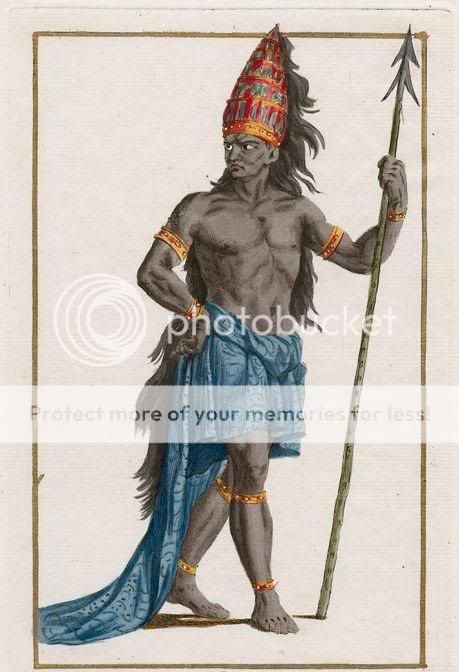

King Nwene Mbata, the first king of the Kingdom of the Kongo

And with that not only did the Catholic Church gain a foothold in Africa but the Kingdom of the Kongo was established and the continent was changed forever.