he'll represent the country pro BonoSonny for president? Now that would be wild

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

When you Wish Upon a Frog (Book II of the Jim Henson at Disney saga)

- Thread starter Geekhis Khan

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

he'll represent the country pro Bono

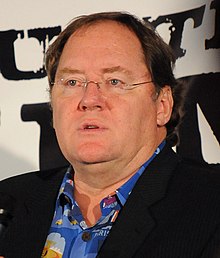

You know........................................................Persistent and Egregious: The Tumultuous Career of John Lasseter

From Animation Underground Netsite, January 7th, 2017

“John Lasseter is the Godfather of CG animation,” said former friend and fellow innovative Icon of the medium Bill Kroyer. “People like to point to Joe Ranft, and yes, Joe – a great friend – indeed deserves the high praise that he gets. But it was John who really had that right combination of vision to see the potential [in CG animation] that Jerry [Rees] and I did and also the drive and determination and political acumen to make it happen. He saw what we did on Tron and almost immediately set to work on [the CG-animated Short] ‘Where the Wild Things Are’, knowing that CG represented the future.”

That Short, of course, spawned the 1986 feature animated film Where the Wild Things Are, which became a surprise hit and is credited in hindsight with kicking off the “Disney Animation Renaissance”. While predominantly hand-drawn, it relied heavily on computer technology, mostly for framing and backgrounds and compositing, but also for the rolling waters of the ocean and the transformations between bedroom and jungle. This “Hybrid” approach, which mixed CG and hand-drawn elements, was further supplemented by the Disney Advanced Technology Animation (DATA) digital ink & paint technology, which then Creative Chief Jim Henson had advanced along with VP Stan Kinsey, with Lasseter remaining a major player in the development and implementation of the technology for animation.

It was, to be true, the moment when CG animation began to grow up and became irrevocably the way of the future, and John Lasseter was undeniably at the very center of it. A jovial, ever-smiling man never seen without a Hawaiian Shirt (the louder the better), Lasseter was beloved by most of his male employees and celebrated by management for his “brilliant eye” and ability to take creative risks and succeed. He was notably less popular with his female employees for reasons that we will get into shortly. Lasseter’s place in the development and promotion of CG animation is pivotal and he’s justifiably known as one of the big names in the industry. And yet, it would be his behavior which would define his career as much as, if not more than, his creative success.

Things accelerated greatly for Lasseter and his CG Dreams when Disney, at his recommendation, acquired Lucasfilm’s Computer Graphics Group (where Ranft had briefly worked on rotation, developing the seminal Wally and the Bee) in whole. With the Lucasfilm group came Operations Head Ed Catmull, a skilled businessman with the vision to see CG animation for the game-changer that it was. Catmull, in turn, found the perfect enthusiastic creative partner in Lasseter, and together they forged the Disney Digital Division, or 3D, Catmull as Operations Head and Lasseter as Creative Head and one of Jim Henson’s “Creative Associates” there to ensure creativity and innovation. It was a match made in creative heaven, a “convergence of computer nerds and art geeks” that was far more than the sum of its parts. This division pioneered not just the DATA inking & painting technology, but the “Pixar” CG animation engine, “Luxo” lighting application, and “Beaker” sound application that dominated the industry until the appearance of Animatriarch. The group would work closely with Steve Jobs’ Imagine, Inc., and the Disney Softworks in general, and help pioneer such revolutionary CG animation hardware as the Disney Imagination Stations and the CHERNABOG compiler, which led in turn to the game-changing MINIBOG and AVE that came after.

Lasseter was critical in establishing the technical state of the art in CG, but he was also critical in establishing the creative “rules” and story methodology that defined 3D and soon Disney as a whole, in particular what would become the Disney Story Commandments. Disney, thanks in large part to Lasseter and the rest of his 3D team, became more multidimensional, nuanced, and emotionally intelligent without losing that classic Disney “delight”.

3D under Catmull and Lasseter soon brought the world groundbreaking digital animation projects. Shorts like Tin Toy Troubles and Knick-Knack amazed viewers at the time not just for technical prowess, but for their fun stories and loveable characters. But Lasseter had his sights set on revolution: the first fully digital, fully-rendered-CG feature film. And he had just the project for it: the 1980 Novella The Brave Little Toaster.

The Brave Little Toaster was greenlit for 1993/4 release as the first all-CG film, and would be Lasseter’s dreams made manifest. With Toaster in production, Lasseter was the undeniable Rock Star of CG animation, with Joe Ranft as his right-hand man and other talents such as Andrew Stanton and Pete Docter and Brenda Chapman waiting in the wings.

But then in 1991 the entire industry was thrown into chaos, starting with Disney itself, when, following the dramatic testimony by Anita Hill that sunk the Supreme Court appointment of Judge Clarence Thomas, the longstanding industry tolerance for sexual harassment and the ill-treatment of women in general was laid bare. Disney led the way in what would become an industry-wide reckoning on sexual harassment and assault. And among those caught up in it all was John Lasseter.

“I’m a Hugger!” (Image source Hollywood Collectibles)

Lasseter had a reputation as a “hugger” with the female employees, giving them unwanted hugs and brief unwanted kisses. He’d also briefly touch women’s legs, seemingly as if to accentuate a statement. At the time, many of his male coworkers didn’t, couldn’t, or possibly wouldn’t see these actions as anything other than the “friendly interactions” that he claimed them to be, particularly since he’d hug his male coworkers too[1].

But female employees in general saw them for the microaggressions that they were, particularly as his body language was different with the female employees. “He’d give the guys a friendly hug, arms only, hips never touching,” one female employee noted. “With the girls, you’d feel his belt buckle and his breath on your neck. It was…really creepy. And unwanted, but you don’t say ‘no’ when the boss wants a ‘hug’.”

Other 3D employees mirrored these actions, or slipped into some of the “old Disney” habits of hanging inappropriate artwork. 3D’s reputation was well known among the female employees, who soon let each other know that 3D was not the place that they wanted to work. Eventually, this information made its way to Cheryl Henson, who’d been assigned by her father to investigate any signs of sexual impropriety within the studio.

Cheryl Henson’s investigation soon came back with two narratives surrounding Lasseter, one predominantly from the men, the other from the women. One narrative portrayed a friendly, jolly, fun-loving guy in Hawaiian shirts who liked kind hugs, and the other narrative portrayed a predatory creep who abused his relative power to cop a quick feel. And the Disney Leadership, particularly Disney Studios Chairman Jim Henson, were in a conundrum.

“Cheryl at first recommended dumping him,” said an anonymous source. “But the Studio Board was adamant that they didn’t want to lose such a talent to another rival studio.”

Further investigation muddied the waters even more. When confronted, Lasseter expressed shock, explaining that he never intended to hurt anyone. “He seemed honestly shocked at the accusations, and hurt,” said Cheryl Henson long after the fact. “Was it an act, or did the sight of my dad crying really get to him like he claimed? I can’t read minds. In hindsight, we decided to give him a second chance, a decision that I supported at the time, but regret now. I guess that we naively believed that we could ‘save’ him, or steer him on the right path.”

But Lasseter did not get off Scott Free. He was suspended without pay, demoted, and temporarily reassigned as a coder in the Disney Softworks. His protégé Joe Ranft ascended to take over his position as 3D Creative Head with Lasseter’s blessing. Lasseter expressed deep remorse to anyone who would listen, and the going assumption was that he truly was regretful for his actions, which he continued to claim he had no idea were hurtful.

Lasseter returned to 3D in the Summer of 1993 following his suspension, demotion, and temporary reassignment. He immediately joined The Brave Little Toaster already in production, becoming a Story Advisor. He seemed enthusiastic, but distracted, to the rest of the team, and was pushing to make some story changes in that were too late into production to make.

“Losing Toaster [to Ranft] was strangely hard for him,” said Pete Docter. “It was like having his baby raised by another. He confessed to me that Joe had done a good job, but after [the film] underperformed, he seemed very irritated. I think that he believed that if he’d been in charge the whole time, that it would have turned out differently. That it would have been a blockbuster. I think that, in hindsight, the silent resentment [for Ranft] really started there.”

And with respect to his treatment of women, at first, he seemed to have learned the error of his ways.

“He was very apologetic,” said Brenda Chapman, who’d had some “uncomfortable interactions” with him while briefly working in 3D and had largely opposed his return to animation. “I was reluctant to keep working with him at first. It was more than the unwanted hugs and the comments, it was the general way in which he made you feel, well, less than. But I basically forced myself to give him a second chance, and for a while it seemed like he really had turned a new leaf.”

While it’s ever a challenge to assess a person’s true intents and motives shy of clairvoyance, reading the witness statements over the course of the years one does get the impression that Lasseter had indeed attempted in good faith to take the lessons that he received to heart, or at least made a good show of it. He stopped the hugs and the leg touching and the comments.

“Yea, I was really glad to see John back,” said Joe Ranft. “He seemed to be his old self in one respect, but also was acting much more respectfully. No more hugs, no complimenting the women on their looks, no little comments among ‘the boys’ about certain physical aspects of ‘the girls’; none of that. I was so happy to have him back, and also glad that he’d learned and grown as a person. But then he met Bakshi.”

Ralph Bakshi is an animation legend in his own right, creator of such monumental adult animated films as Fritz the Cat, Wizards, Howard the Duck, and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and such classic animated television shows as The New Rocky and Bullwinkle, Hoerk & Gatty and Junktown. Many of these later works were done in partnership with John Kricfalusi, and their Bakshi-Kricfalusi Productions gained a reputation for pushing the very limits on animation subject matter and content to the degree that they were generally referred to as “Batshit Productions”. BKP had been hit hard by revelations of multiple, systemic, and egregious abuses of their female employees including severe sexual assault and a persistently hostile working environment exacerbated by limited opportunities for female animators elsewhere. The resulting class-action lawsuit led to the implosion of BKP.

Bakshi reportedly approached Lasseter in 1994 after the release of The Brave Little Toaster. Bakshi wanted to partner with Lasseter in a new studio “away from where the chicks are running the show.” Lasseter politely turned him down, though the two maintained contact and would meet occasionally for drinks. Over time, Lasseter would use Bakshi as an ersatz “confessional” for his frustrations, and Bakshi happily listened, and gave him supporting advice. Alas, the advice was not helpful.

By 1995 Bakshi had put together what he called a “support group” for animators and other creative artists “taken down” by “uptight feminists”. Eventually, one of them dubbed the club G.R.O.S.S. for “Get Rid Of Slimy girlS”, the name taken from a Calvin and Hobbes cartoon[2].

The Inspiration for G.R.O.S.S. (Image source Twitter)

“It was like a support group, ‘Gropers Anonymous’, call it,” said one member, who spoke on terms of anonymity. “I feel like most of us just saw it as a chance to vent our frustrations for the bad decisions that we made, maybe make a few jokes at the expense of the women who we felt wronged us, and John was totally of that type at first. But some, well, they truly believed that there was some sort of Feminazi assault on Manliness going on and saw themselves as Warriors of the Y Chromosome, or something. I figured that they were just blowing off steam and joking around, but I guess that they really meant it. Whether John was pulled into the latter way of thinking, or whether he always felt that way and Ralph just gave him the excuse that he needed to drop the façade I can’t quite say. But as the months and years went by, he increasingly saw himself as the victim.”

The first 3D project post-Toaster would be Andrew Stanton’s Finding Nemo, a highly-successful picture greenlit by Jim Henson in 1992 with the express intent to release in 1995 coincident to the opening of the DisneySea Resort in Long Beach, California. The decision had been made while Lasseter was on reassignment, so he had no say in the matter, but even so, Lasseter seemed to expect to lead the next CG feature and was put out when Stanton was named to Direct.

“John wanted to take the helm,” Ranft recalled. “But it was Andy’s project. I made it clear that John could lead the next picture, which we all realized should be his Toys idea.”

But Lasseter seemed to set aside his resentment and became a driving force in the creative process. He was very professional and supportive for the female animators, in particular Patty Peraza, who’d been selected to do the character animation on the humpback whale Limpet and her calf Squirt. “He was at first being a real mentor-figure for her,” said Stanton. “He gave her good advice and could lean in to give advice without grabbing her shoulder or sniffing her hair or anything. Of course, he pushed back a bit on her creative suggestions, but seemingly no worse than he’d do with, say, Jorgen [Klubien].”

“The biggest problem that Joe had with John on Nemo was occasionally having to remind John that Andy was in charge,” said Mike Peraza, who was leading animation on Nemo’s older brother Anchor. “Patty was saying good things about him, and I was starting to become his friend.”

Things seemed to change slightly when production on Finding Nemo ended and production began on The Secret Life of Toys. He was now the undisputed leader, head of storyboards and direction. And his attitude seemed to shift fairly quickly. “He was much more demanding and far less flexible,” said Jorgen. “He was acting much like he did when he was in charge [of 3D]. He sometimes even went behind Joe’s back on decisions, which made us uncomfortable. He didn’t like including the Christmas Toy characters and he really didn’t like that Frank [Oz] was brought in to do character backgrounds. It was all a challenge to his authority. But the true difficulty really started with Patty.”

At first Lasseter had returned to his mentorship role with Patty Peraza, who was animating the Barbie spoof Big Sur Cindy. It began well enough, but then Lasseter pushed back on her character study. “Patty wanted to make Cindy into a smart, intellectual girl who’s always underestimated because of her looks, more ‘Doctor Barbie’ and less ‘Malibu Barbie’,” said Klubien, “But John wanted her to be this Valley Bimbo that all the other toys gawked at.”

The dispute started small, with Peraza insisting that Cindy “needed to be taken seriously,” but Lasseter insisting that it would be “funnier” his way. She tried various combinations and middle-ground variations, but Lasseter continually pushed her towards the “Beach Bimbo Barbie” (her words) approach. After a while, her suggestions became a sore spot. “I think that he saw Patty’s recommendations not as the useful suggestions of a fellow animator,” said Patty’s husband Mike, “but as a challenge to his authority. There was also something…else going on. Each and every time Patty made a suggestion, he responded by pushing for Cindy to be sexed up even more; more sway to the hips, more ‘hey, boys!’ moments, as if each attempt by Patty to make her less Goldie Hawn and more Reese Witherspoon was taken as a threat to his ‘vision’ and responded to with a counteroffensive. And then Patty described one day where he just snapped at her. She’d said ‘I feel it’s my job to be honest about my opinions,’ and he yelled, ‘Your job is do what you’re told!’ She ran to me crying.

“When I confronted him, he apologized to me then her, and told me that it was ‘work stress’, so I let it go. But that was just the start.”

Lasseter’s mood continued to darken, particularly with respect to the female employees. “He stopped looking at me like a colleague,” said Patty Peraza, “and started looking at me like a combination threat and entrée.”

“I was on the verge of punching him,” said Mike, “or going to the union. Joe [Ranft] promised to intervene.”

When Ranft ultimately took Patty’s side in the dispute over Big Sur Cindy, Lasseter said “Et tu, Joe?” with a large smile and laugh that seemed to defuse the tension, but witnesses note that “you could still sense the anger. John had meant it.”

Following the “talk”, Lasseter appeared to return to his more professional, less toxic behaviors, but behind the jovial façade he was increasingly seeing Ranft less as a friend and more as an obstacle. Things became compounded during pre-production on what became Bug Life, where his idea for a “Grasshopper and the Ant” narrative was rejected in favor of a separate “Army Ants” idea. He was the Director and Story Lead, but the “story” was taking on a life of its own, with Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls getting hired for the lead roles of Flit and Raid only for them to start rewriting the characters around their own preferences. And while such changes were typical and had even happened on The Secret Life of Toys with Antonio Banderas giving a whole unintended “Zorro vibe” to the character of Buzz. But feeling like his “vision” was increasingly “besieged”, Lasseter took the changes personally. This anger carried over into The Secret Life of Toys, still in final animation.

“The production [on Toys] became increasingly difficult,” Ranft said. Lasseter was “playing along” in the words of his coworkers, but he was showing renewed passive-aggressive tendencies and frequent microaggressions against the female team members in particular. Patty Peraza, who once saw him as a potential mentor and ally, now did her best to avoid prolonged contact.

“It would have been easy if he’d just grabbed my ass, or something,” she said. “Then I could file a formal complaint and he’d be gone. But he never did anything that overt, or actionable. He’d, say, give me a look that just made me feel, well, yucky, and it would be so subtle that I had to wonder if it was something that I was misinterpreting. I could say that he was making me ‘uncomfortable’, but all that management could do was talk to him and have him deny it. Joe and Jim [Henson] met with him a couple of times, and things seemed to improve again.”

But then, just as The Secret Life of Toys was in final editing, things got noticeably worse very quickly. In early 1997 a visibly upset Ralph Bakshi told the assembled members of G.R.O.S.S. that his friend and partner John Kricfalusi had been arrested, he said for “flirting” online with young women. The FBI was much less flippant in their assessment of his actions, calling it “soliciting sex from a minor”. Kricfalusi would commit suicide in his cell, hanging himself from his bedsheet. Bakshi called it “murder”.

“Kricfalusi’s suicide hit John hard,” said the same unnamed G.R.O.S.S. member, “Though he didn’t see it as a ‘suicide’. Ralph had him convinced that the guards had ‘arranged’ something. He wondered if something like that would happen to him next. I joked ‘just don’t troll for teenagers on the net and you’ll be fine,’ but he just scowled at me. I stopped going to G.R.O.S.S. after that. The vibe had shifted into something really nasty.”

Following Kricfalusi’s death, Lasseter became more openly hostile and aggressive. He openly defied Ranft’s production and openly talked down to female employees. On top of that, several of the male animators were starting to act similarly. It turns out that Lasseter wasn’t the only member of G.R.O.S.S. on the production. The “boy’s club” had already become noticeable as Lasseter and a small group of male animators, a couple of whom had, like him, been reprimanded in the past for various improprieties, were increasingly seen hanging together at the cafeteria or outside on the Disney Campus. It became increasingly apparent that there was going to be an ugly reckoning, with HR already compiling the complaints and consulting the Legal Weasels, when Lasseter and the G.R.O.S.S. crew all turned in their two-weeks’ notices at once.

Unbeknownst to Joe Ranft or anyone else, Lasseter had already made contact with Chris Wedge at Blue Sky Studios. Wedge had recently made a name for himself in the CG animation game for his Short CottonTale, and now former 20th Century executive Chris Meledandri had come on as CEO for the small studio, bringing with him the support of Filmation Studios, who agreed to underwrite the small studio as it spun up a feature animation department. Unaware of Lasseter’s growing behavior issues, Meledandri hired Lasseter as the President of Feature Animation and Chief Creative Officer. Lasseter took many of the G.R.O.S.S. crew with him and even hired some of the “Saboteur 35” who’d deliberately tried to sabotage production on Universal Animation’s Spirit of the West out of spite against CCO Jeff Katzenberg, including slipping pornographic images into the background of shots.

While Disney and Joe Ranft quietly thanked their stars that the “problem” was gone, openly hoping that the new opportunity would give Lasseter a chance at a fresh start and another chance at self-realization, in reality the “problem” had just moved[3].

[1] This has not yet reached the level of the egregious “feeling up” that he was accused of doing in the 2000s and 2010s, where the women of Pixar had developed a technique that they called “The Lassiter” for crossing their legs and keeping their hands in their laps to keep his hands from “going further”. At this point, it’s a “quick squeeze on the knee” and at this point these early aggressions were looked past by management as “friendly” rather than “predatory”. As noted in earlier posts, abuses tend to start “small” and escalate as the perpetrators “get away” with things.

[2] Calvin & Hobbes creator Bill Watterson was reportedly irate to hear about this.

[3] So, once again it’s time to read minds while grabbing a third rail with both hands. As I have stated before, it is always a challenge to address issues where you lack the facts and individual reputations are getting called into question. Moving beyond issues about if someone is “born” bad or “made” bad, it’s a real challenge to look at individual cases where accusations of inappropriate behavior have been made and then make judgement calls. It’s very easy to err either way, so I try to stick with the limited known “facts” and try to extrapolate them onto this timeline’s specific circumstances. It’s fairly straight forward in cases of egregious sexual assault or quid pro quo, particularly where a jury has made a clear indication of guilt (e.g. Harvey Weinstein). It’s harder in cases of Hostile Work Environment, because that can be very subjective.

In the case of John Lasseter, the accusations, if accurate, indicate persistent, egregious, and systemic sexual harassment and a textbook hostile working environment as well as frequent sexual assault (forced unwanted hugging and kissing, persistent and “ascending” leg touching) that grew to a level that there were ultimately multiple allegations of inappropriate behavior from a large swath of the female employees made against several males in the employ of Pixar in the 2000s and 2010s, Lasseter chief among them. When I first began this timeline, my research gave a situation that was very muddled, with Lasseter’s intentions impossible for me at the time to discern, particularly since the worst of such alleged abuses in our timeline was over a decade in the future of this timeline, and I wondered if there was “hope” to prevent things from ever reaching the persistent and egregious level of Pixar in our timeline, but as I dug deeper into the allegations, the results spoke not to a man unaware of the inappropriateness of his behavior, but to a man who used and abused his power and weaponized his sexual aggressions as a predatory and discriminatory tactic for keeping female employees on the outside of the “boy’s club” and “in their place”.

Parallel accusations by Jorgen Klubien and Henry Selick about his aggressive micromanagement and unreasonable and shifting demands, if true, also speak to me to a man who tears down and sabotages (or flat out steals) other creative people’s work, as if seeing them as a threat. To me, this speaks to a person with power issues and aggressive insecurity.

Again, it’s hard to definitively say what happened when the full set of facts are unknown, but the many accusations, if true (and I have no reason to doubt their veracity) seem really, really egregious and unjustifiable to me. Cassandra Smolcic’s allegations are just sickening (warning: frank and graphic depictions of sexual assault).

So, could this fictionalized Lasseter have been “saved” from perpetuating abuse (as part of me honestly wanted to believe, as I like to believe in second chances), or was he predatory by nature? Was he on the “road to recovery” and backslid, or just faking, possibly to himself? Was Bakshi leading him astray, or did he want to have his predatory and misogynistic inclinations justified and Bakshi and G.R.O.S.S. simply provided him that avenue? Who in the hell knows? You can frankly see me trying to answer these questions myself in the writing of this post, and I very deliberately left things muddied and open to interpretation both to add verisimilitude and because I don’t have any definitive answers to the questions and uncertainties myself. This post represents my best good faith attempt at portraying a fictional situation with no personal malicious intent to any real person.

And a MASSIVE CAVEAT that all of this is a work of speculative fiction based on limited publicly-available resources. I’m not clairvoyant and have no special knowledge about the intentions and beliefs of Lasseter, Bakshi, or any other real person. Accept nothing that I say here as factual or an accurate reflection on reality or the inner thoughts and desires of any of the real human beings being fictionally portrayed here. Your guess as to the reality is as good as mine.

After everything I just read.............

If this craphead's really gonna drag them don, then I'd rather see Blue Sky and Filmation go under some SERIOUS restructuring or even close outright, but the latter option's not realistic as Triad would probably want to keep a animation unit.

Finding out about LOLA was a welcome surprise, and certainly one of the better Disney-based articles from the late 90s.

Same here.Finding out about LOLA was a welcome surprise, and certainly one of the better Disney-based articles from the late 90s.

TSR, the company behind the iconic Dungeons & Dragons roleplaying game and similar products, had long had a very open and permissive relationship with its fans, going back to its early days in the late 1970s. “Homebrew” adventures, rules, characters, and monsters were de rigueur, and even occasionally got adopted by TSR as Canon.

My favourite story about this (and I'm not saying it's true, but I definitely heard it somewhere) was the time someone from TSR phoned up Ed Greenwood and said that his Dragon Magazine articles seemed to be set in a well-defined world, would he be interested in selling it to TSR to be the flagship setting for D&D 2nd Edition? And Greenwood said something like "It's your game, it's being published in your magazine, I assumed you already owned it." After a brief pause, the TSR rep said they woudn't tell anyone that Greenwood had said that, and they'd be in contact to make a deal.

Here's the article where like under Bakshi is described, and also features some other accusations about the Animation industry in general, if you or anyone else wanted to go there.Yikes.

I mean, with Bakshi I didn't know since I didn't find much in my admittingly little overview. And yikes, the whole thing sounds freakin bonkers. But this is not gonna end well for them.

Inside The Persistent Boys Club Of Animation

Women who have worked in animation for anywhere from a few years to six decades talked to BuzzFeed News about how things have gotten better — and how they haven’t.

While pretty awful at times, there are some really positive things in there too, like the assumptions by the women that most of the men they worked with are good people, not toxic jerks, and would be horrified to learn some of these things and would generally be supportive.

“They’re really good people, and they would be horrified to learn that they’re excluding people,” said a production manager who worked at Pixar and who, along with Anastasia, initially wanted her name on the record and later asked to be anonymous.

Also, Glen Keane comes across as a real Mensch here, really being there to mentor Carole Holiday.

Just when you think it can’t get any better, Disney avoids joining the Dark Side.

I got a lot of questions about how Disney iTTL would handle the Sonny Bono Act, and I really wasn't sure until, ironically, the controversy over Wizards of the Coast's OGL 2.0 erupted. Also, the burgeoning entry of Mickey and Oswald into the Public Domain had it on my mind. The two events crashed in my head and the LOLA idea came out.Finding out about LOLA was a welcome surprise, and certainly one of the better Disney-based articles from the late 90s.

Sonny lives, I hopefully look forward to his next political campaign with the slogan "I've Got You, America!"

Sonny for president? Now that would be wild

Well, I'll run this by jpj, but no promises. Bono isn't really a top tier candidate even in Cali.Oh, boy! A Bono administration would be a riot!

he'll represent the country pro Bono

YES! Let the Pun flow! Spread the suffering!

Last edited:

Pretty much any industry dominated by mostly straight men is going to have a problem. Video games, films, journalism, comic books all have the problem. I've noticed that when tv shows tend to have female writers they're more willing to call out something sexist or awful. Some comments about Berserk I've read implied that while Kentaro Miura was never an outright sexist some of his earlier stuff fell into odd territory, and that meeting and befriending a female writer helped him improve his portrayal of women. Altered Carbon benefitted from having a female show runner.

Diversity and gender balance won't completely remove the problem but it will help.

Diversity and gender balance won't completely remove the problem but it will help.

Last edited:

I'd seriously disagree with that. Any industry where talent is perceived to be incredibly rare will have problems with culture. Because of the belief (real or not) that certain people cannot be replaced their bad behaviours will be tolerated, management will minimise or ignore complaints because they do not want to risk losing the 'star'. That will come out in different ways but the culture will always end up toxic.Pretty much any industry dominated by mostly straight men is going to have a problem. Video games, films, journalism, comic books all have the problem.

Lasseter did not behave like he did because he was in a male environment, that was just who he was. He behaved that way because he got away with it and so pushed boundaries. Had management stamped on it earlier he may never have been a nice person to work with, but he'd have kept it professional for fear of being sacked. Or he had been an idiot and got sacked. Either way the problems would never have got so bad.

Being overly male dominated DOES play a role. DC Comics HQ was in many ways a frathouse, as was Blizzard. Yeah the need to protect perceived talent is definitely a thing but sexism is another element.I'd seriously disagree with that. Any industry where talent is perceived to be incredibly rare will have problems with culture. Because of the belief (real or not) that certain people cannot be replaced their bad behaviours will be tolerated, management will minimise or ignore complaints because they do not want to risk losing the 'star'. That will come out in different ways but the culture will always end up toxic.

Lasseter did not behave like he did because he was in a male environment, that was just who he was. He behaved that way because he got away with it and so pushed boundaries. Had management stamped on it earlier he may never have been a nice person to work with, but he'd have kept it professional for fear of being sacked. Or he had been an idiot and got sacked. Either way the problems would never have got so bad.

Eh, there’s nothing stopping a female-dominated workplace from being a toxic environment…

The Man who Would Be Emperor

On the Road to El Dorado

Post from Animation, Stories, and Us Net-log, by Rodrick Zarrel, October 5th, 2012

A Guest Post by @Nerdman3000

Going in 1998, Universal Animation was on a high, having hit a winning streak when managed to release the smash hit Heart and Soul in 1996 and the modest success 1997’s Spirit of the West. If one went further to the animation studios Hollywood Animation/pre-Universal merger days to count Retriever, then the studio’s success became even more clear.

The animation studio had managed to survive the threat of Jeffrey Katzenberg axing them and even gained newfound expanded independence that was practically unheard of for any such large animation studio under a corporate ownership. Not even Disney Animation had as much seemingly complete independence as Katzenberg unwittingly gave them going into 1998, as Katzenberg was simply content to sign off on anything Cohn brought before him as long as they didn’t go massively over budget.

It was perhaps unfortunate then for the animators that Universal Animation was about to find their winning streak abruptly ending and their newfound independence tested when their late 1998 film East of the Sun and West of the Moon bombed hard at the box office.

Some concept art from Don Bluth’s version of East of the Sun and West of the Moon from the 80’s. (source: Cartoonreseach.com; combined by @Nerdman3000 into one image)

The 1998 film was one with a surprisingly long and storied nearly 20-year history, beginning life in a way as Don Bluth’s intended follow-up to The Secret of NIHM. When that film bombed, however, the project found itself quietly cancelled by Columbia Pictures while Bluth himself left the studios. Still, it would not be the full end of the story, as during his time partnering with Hollywood Animation, Bluth had often expressed interest in the possibility of resurrecting the project in some form, even coming up with ideas for a revamp of the film’s story.

When Bluth ended his partnership with Hollywood Animation and partnered instead with Katzenberg’s predecessor and chief rival Michael Eisner at Columbia, an enraged Jeffrey Katzenberg almost immediately began looking into adapting East of the Sun and West of the Moon, if mainly only to deny Bluth the chance of resurrecting the project for Columbia. The announcement reportedly left Bluth “frothing at the mouth” and raging, which reportedly greatly pleased Katzenberg, especially since Bluth had been considering resurrecting the project for one of the three films, he had signed on to produce at Columbia[1].

Following the merger with Universal in 1995, Katzenberg would assign a majority of the animators coming over from Universal to form a small team to begin working on the film, which Katzenberg wanted to go head-to-head with Bluth and Eisner’s Beauty and the Beast film, with Charles Grosvenor and Roy Allen Smith co-directing the film. As they would quickly find, the task before them was not an easy one.

The song which shares the same name as the film, most memorably sun by Ella Fitzgerald. For this timeline’s film, Whitney Houston will do a memorable cover of the song.

As they quickly found, they wouldn’t be able to reuse much of Bluth’s original story concepts and ideas for the film when he was making it in the 80’s due to Columbia owning the production rights to Bluth’s original 80’s story pitch. That version would have been a sci-fi take on the tale, set hundreds of years in the future and following a boy who is a fugitive from another world, who must be rescued by the film’s female heroine after she causes him to be discovered and taken away to be put to death[2]. When Bluth partnered with Hollywood Animation, he had sketched some ideas for a revamped story which would completely drop the Sci-Fi aesthetic that Bluth had originally intended for a more faithful adaptation of the Norwegian tale. Thankfully for Grosvenor and Smith, enough people around at Universal Animation who’d worked with Bluth and had heard some of his revamped story ideas for the film to allow them both to have a head start on the project.

The film would follow a young peasant girl named Eivor (played by Cameron Diaz) who sets off on a journey east of the sun and west of the moon with a polar bear, whom she has discovered is actually a prince named Oskar (Jeff Goldblum) who had been cursed by his wicked stepmother (played by Helen Mirren). They hope to break Oskar’s curse. The decision to not follow Bluth’s original pitch would end up pleasing Katzenberg quite a bit as he believed that would help the film against Disney’s upcoming 1998 animated film, Heart of Ice. Universal’s film was also expected to release toe to toe against Bluth’s upcoming Beauty and the Beast film.

Unfortunately for East of the Sun and West of the Moon, it would that very three-way dueling film strategy Katzenberg wanted to run with that would ultimately doom the film itself. Despite some modest good reviews and praise towards the film’s cast (particularly Diaz and Mirren) and score by Han Zimmer, the film had the unfortunate luck of releasing a week before Disney’s biggest and most successful animated film since The Lion King, a massive unexpected success that could honestly be best compared to Universal’s own Heart and Soul film released two years before. Making just $62 million against a $75 million budget, East of the Sun and West of the Moon would experience a now infamous 82% drop on its third weekend as Heart of Ice began to completely sell out in theaters. Worse, the film had likely only avoided an even worse fate at the box office by the skin of its teeth due to Columbia and Michael Eisner moving Beauty and the Beast forward a whole month[3].

As Roger Ebert famously said when reviewing his favorite and least favorite films of the year, East of the Sun and West of the Moon had the unfortunate luck of being a good animated film that released between two of the greatest animated masterpieces of all time, one of them an animated box office titan.

Roger Ebert, who is particularly notable for liking East of the Sun and West of the Moon, put it as one of his favorite animated movies of the year 1998. (source: Pinterest)

In light of the film’s box office failure, the entire animation studio was unsurprisingly left scrambling and wondering what this would mean for the studio and how Katzenberg would respond, especially when the film’s failure could arguably be thrown at his own feet. Would their newfound independence be cut short? Would Katzenberg use the film’s failure to finally put an axe to the studio as he originally wanted?

They soon got their answer from Katzenberg when he announced there were going to be a small number of layoffs at the studio in order to cover the costs of the film’s failure. Those who had worked on EotSaWotM, like Grosvenor and Smith, would find themselves scapegoated for the film’s failure and bear the full brunt of the layoffs, with those that survived being merged into the team working on the studios upcoming City of Gold film. When confronted by Cohn over the layoffs, Katzenberg reportedly claimed that the removal of the animation team responsible for the film was in fact always planned by him[4]. This did little to sooth hurt feelings, as many at the animation studio were left with a bitter taste in their mouth and feeling angry at Jeffrey Katzenberg.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it wasn’t long before a number of caricature images from the animators mocking or attacking Katzenberg found themselves once more being passed around the studio. No doubt very much aware that the last thing the animation studio needed was Katzenberg catching wind of mocking him, Marjore Cohn was quick to try and put a stop to it. Yet this did little to put an end to the noticeable tension that was in the air as the studio turned to their next film, 1999’s City of Gold.

+

+

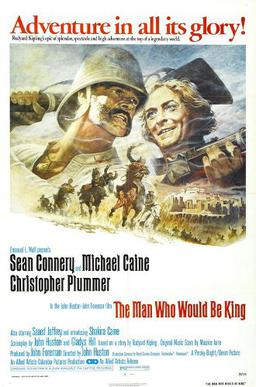

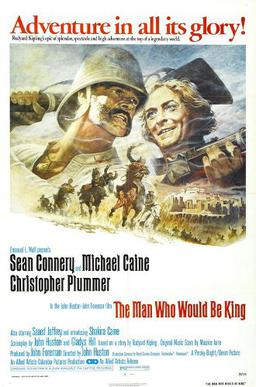

Basically, think our timeline’s Road to El Dorado + 1975’s The Man Who Would Be King and you'll get a pretty good idea for the story of City of Gold. (source: wikipedia.com)

City of Gold had technically been in production for a number of years, having actually been greenlit by Katzenberg after he had taken over. Katzenberg, as he later recalled, had been inspired by Hugh Thomas’s Conquest: Montezuma, Cortes and the Fall of Old Mexico and thought an animated film set in the Age of Discovery could work well. After the Universal merger, he would assign a small development team of animators made up of those who hadn’t been assigned to work on EotSaWotM, though for the most part production on the film trudged along slowly. It wasn’t until mid-1996 that production on the film would truly jumpstart, partially because Katzenberg wanted to find a particularly good screenwriter to work on the film.

At that point in time, Universal had only just started to fully embrace the recent animation practice of hiring a screenwriter to write the screenplay for an animated film, instead of the old traditional storyboard storytelling production style that was once the norm in animation. It had been a practice adopted by Disney a few years earlier and Katzenberg had fully embraced it for Spirit of the West, where he quickly found that he much preferred it over the older storyboard storytelling that was more commonly used during his time at Hollywood Animation.

Katzenberg, wanting to capture the adventurous and comedic tone found in Disney’s Aladdin, reportedly first approached the writing duo of Ted Elliot and Terry Rossio who had written the film Aladdin and asked them to come on board. Both said no, wanting to stay at Disney and ironically went on to write Disney's 1999 City of the Sun film, which would release the same year as City of Gold and lead to Katzenberg crying foul. With Elliot and Rossio spurring him, Katzenberg turned it over to Marjore Cohn, who in turn gave the task over to three relatively new writers named Philip LaZebnik, Jonathan Aibel and Glenn Berger[5].

Not longer after, the three presented Jeffrey Katzenberg and Marjore Cohn with a story treatment inspired partially by 1975’s The Man Who Would Be King, but set during the Age of Discovery and the lost city of El Dorado replacing Kāfiristān, which they would approve. The film’s story would follow an elderly former conquistador named Nicolás (who is based on Dravot), who recalls to a young Spanish adventurer named Tulio (who is clearly takes on Rudyard Kipling’s role in the story) of an adventure he had in his youth, were he and another conquistador named Diego (who is based on Carnehan) traveled to the Americas during the Age of Discovery and found the legendary city of gold, El Dorado. There they manage to be proclaimed as living gods by the natives after Nicolás survives an arrow unharmed (due to it being blocked by his cross necklace), and Nicolás is proclaimed King of El Dorado while Diego is proclaimed as his faithful servant. Taking advantage of the mistake, the two men decide to play along with it, helped along in their con by the beautiful Atzi, whom is betrothed by the natives to the newly crowned Nicolás but quickly discovers their deception. Soon, as the power begins to go to Nicolás’s head and Diego finds himself falling in love with Atzi, the two find themselves being viewed with suspicion by the High Priest Xiuhcoatl, who threatens to, and eventually does, expose their con.

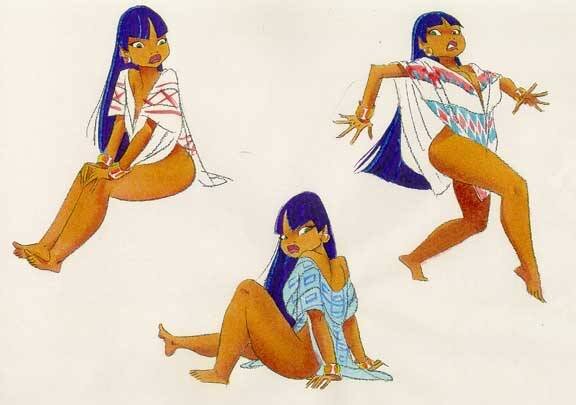

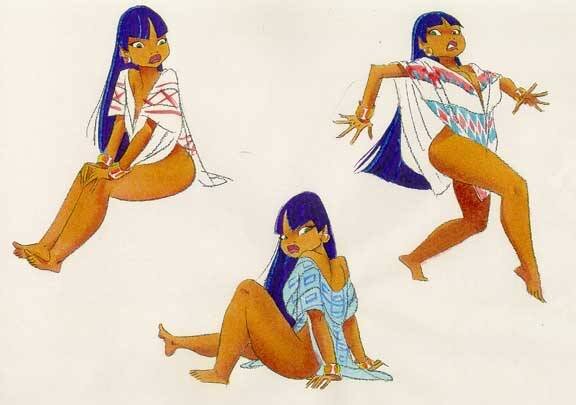

Concept art for the film featuring Atzi, the native woman who helps the films main conquistador duo, as played by Rosie Perez. (source: characterdesignreferences.com)

Unlike 1975’s The Man Who Would Be King, the film would drastically differ in it’s ending. Here Nicolás survives, but takes on Carnehan’s role in that he is the one that loses everything and ends up being the one who meets with and shares his story with Tulio. Diego meanwhile also survives, but ends up staying with the natives and manages to replace Nicolás as King as well as goes on to marry Azti. Most critics would later regard the film having the natives still accept Diego and even going on to let him be their king after finding out he conned them, simply because of the two he was much kinder to them, to be a little forced if not outright a bit demeaning to the natives. The irony here of course is that it actually was forced on the writers, by Jeffrey Katzenberg no less.

For those unaware, LaZebnik, Aibel and Berger originally wanted to give the film a darker ending, which would have stuck closer to the ending of The Man Who Would Be King. In their original ending, Nicolás would have died like Dravot does in the 1975 film while Diego is the one who is forced to escape El Dorado alongside Azti, the later of whom who is implied to have died afterwards due to disease, which was originally going to be implied was slowly infecting the natives of El Dorado due to Nicolás and Diego spreading it to them. Now old, alone, and bitter, it would therefore be Diego who would go on to later meet with Tulio and try to discourage him from his desires for adventure by sharing his tragic story.

Katzenberg, however, reportedly didn’t like that intended ending, and considering this was late 1996/early 1997 when he still bothered to care about what Universal Animation was doing, he sadly forced them to change the film’s ending to what would be the final result we see today. Personally, I actually think the original intended ending sounded so much better, but oh well.

Regardless, production on the film would remain slow going for a number of months until the release of Spirit of the West, even as Andrew Adamson signed on to direct. It was only after the release of Spirit of the West that a number of animators involved in that film would move on to work on and complete City of Gold. By Late 1997, casting was already underway as Mel Gibson, Ray Romano, and Rosie Perez would each sign on to play the films three main characters Nicolás, Diego, and Atzi, while joining them would be Jeremy Irons as High Priest Xiuhcoatl and Grant Shaud as Tulio. Further hired to work on the film would be Han Zimmer, John Powell, and Matthew Wilder[6], who would each score and write music for the film.

Mel Gibson, Ray Romano, and Rosie Perez, the stars of Universal's City of Gold, circa 1999. (source: alamy.com; combined by @Nerdman3000 into one image)

Looking to avoid a repeat of the disastrous release of EotSaWotM, Cohn managed to convince a initially reluctant Katzenberg to put some distance from the release of Disney’s City of Gold at Thanksgiving 1999 release, City of the Sun, leading to the film eventually releasing on Memorial Day 1999, where it received mixed to positive reviews, with most complaints being labeled at the film’s ending and Rey Romano’s infamous and atrocious singing[7], even as praise was heaped on the film’s story (minus the ending, which some criticized as being needlessly happy), Jeremy Irons’ performance, and the film’s music. While the more mixed reviews did sting for Universal Animation, it was more than made up by the movie’s success at the box office, where it made an excellent $348 million worldwide. Further success was found upon its home video release, where it even managed to do decently in its home video release.

Still, with Universal having released an animation box office bomb followed by a more critically film mixed film, some in the industry as the new millennium began were left to wonder if the bad times would continue at Universal Animation and whether Katzenberg should tighten the leash that he had loosened on the studio, especially as Universal Animation geared to release two separate animated movies in 2000.

[1] Before ultimately deciding to go with Ruler of the Roost for Bluth’s third film at Columbia as part of his deal with Eisner, he originally had been hoping to resurrect East of the Sun and West of the Moon. Unfortunately, Hollywood/Universal Animation publicly announced their intention to adapt the story in question before Bluth did, forcing Bluth and go to go back to the drawing board.

[2] Part of me suspects that a lot of Bluth’s ideas here eventually went into Titan A.E. in our timeline.

[3] What makes this somewhat ironic is that after the move but before the release of Heart of Ice, Katzenberg would often privately mock Eisner and Bluth for having blinked. After the massive release of Heart of Ice, however, Katz convinced himself that Bluth and Eisner had somehow known what was going to happen and that they had in fact tricked him with the move.

[4] Since most of the animation team working on the film primarily belonged to those who had worked at Universal Animation before the merger with ABC and Hollywood Animation, this meant that the layoffs pretty much gutted most of the talent who worked at Universal before the merger. Things are a bit more complicated, since there are both truths and falsehoods here. Katzenberg’s original plan indeed was to have Cohn split the animation team that was working on EotSaWotM into three after the film’s release and have the animators simply join the three main teams that were working on City of Gold, Atlantis, and John Carter. No matter what, the animation team responsible for EotSaWotM was going to end. They weren’t however supposed to actually be laid off, like Katzenberg ultimately did.

[5] Elliot and Rossio in our timeline went to work on Road to El Dorado. Here they work on City of the Sun, leading Katzenberg to accuse them of stealing his idea. Philip LaZebnik in our timeline wrote the screenplay for Pocahontas, Mulan, and Prince of Egypt. The writing duo of Jonathan Aibel and Glenn Berger meanwhile wrote the Kung Fu Panda and Trolls movies in our timeline. The three will ultimately become a writing trio in this timeline.

[6] While Powell and Zimmer are the same as in our timeline’s Road to El Dorado, the inclusion of Matthew Wilder (who wrote the music for our timeline’s Mulan) is a new one. With Wilder on board, the film’s music ends up becoming much more well received and fondly remembered then the music from our timeline’s film.

[7] A bit of a joking nod here to the Ray Romano sings videos, which you can find on YouTube. Long story short, after Gibson decides to sing his parts in the film (similar to what he did in our timeline’s Disney's Pocahontas), Romano asks to also be allowed to sing his part rather than get someone to record over him. Most people afterwards agree it was a bad idea to let Romano sing (especially since his singing role in the film was more substantial than Gibson’s) and that it should have been dubbed over.

Post from Animation, Stories, and Us Net-log, by Rodrick Zarrel, October 5th, 2012

A Guest Post by @Nerdman3000

Going in 1998, Universal Animation was on a high, having hit a winning streak when managed to release the smash hit Heart and Soul in 1996 and the modest success 1997’s Spirit of the West. If one went further to the animation studios Hollywood Animation/pre-Universal merger days to count Retriever, then the studio’s success became even more clear.

The animation studio had managed to survive the threat of Jeffrey Katzenberg axing them and even gained newfound expanded independence that was practically unheard of for any such large animation studio under a corporate ownership. Not even Disney Animation had as much seemingly complete independence as Katzenberg unwittingly gave them going into 1998, as Katzenberg was simply content to sign off on anything Cohn brought before him as long as they didn’t go massively over budget.

It was perhaps unfortunate then for the animators that Universal Animation was about to find their winning streak abruptly ending and their newfound independence tested when their late 1998 film East of the Sun and West of the Moon bombed hard at the box office.

Some concept art from Don Bluth’s version of East of the Sun and West of the Moon from the 80’s. (source: Cartoonreseach.com; combined by @Nerdman3000 into one image)

The 1998 film was one with a surprisingly long and storied nearly 20-year history, beginning life in a way as Don Bluth’s intended follow-up to The Secret of NIHM. When that film bombed, however, the project found itself quietly cancelled by Columbia Pictures while Bluth himself left the studios. Still, it would not be the full end of the story, as during his time partnering with Hollywood Animation, Bluth had often expressed interest in the possibility of resurrecting the project in some form, even coming up with ideas for a revamp of the film’s story.

When Bluth ended his partnership with Hollywood Animation and partnered instead with Katzenberg’s predecessor and chief rival Michael Eisner at Columbia, an enraged Jeffrey Katzenberg almost immediately began looking into adapting East of the Sun and West of the Moon, if mainly only to deny Bluth the chance of resurrecting the project for Columbia. The announcement reportedly left Bluth “frothing at the mouth” and raging, which reportedly greatly pleased Katzenberg, especially since Bluth had been considering resurrecting the project for one of the three films, he had signed on to produce at Columbia[1].

Following the merger with Universal in 1995, Katzenberg would assign a majority of the animators coming over from Universal to form a small team to begin working on the film, which Katzenberg wanted to go head-to-head with Bluth and Eisner’s Beauty and the Beast film, with Charles Grosvenor and Roy Allen Smith co-directing the film. As they would quickly find, the task before them was not an easy one.

As they quickly found, they wouldn’t be able to reuse much of Bluth’s original story concepts and ideas for the film when he was making it in the 80’s due to Columbia owning the production rights to Bluth’s original 80’s story pitch. That version would have been a sci-fi take on the tale, set hundreds of years in the future and following a boy who is a fugitive from another world, who must be rescued by the film’s female heroine after she causes him to be discovered and taken away to be put to death[2]. When Bluth partnered with Hollywood Animation, he had sketched some ideas for a revamped story which would completely drop the Sci-Fi aesthetic that Bluth had originally intended for a more faithful adaptation of the Norwegian tale. Thankfully for Grosvenor and Smith, enough people around at Universal Animation who’d worked with Bluth and had heard some of his revamped story ideas for the film to allow them both to have a head start on the project.

The film would follow a young peasant girl named Eivor (played by Cameron Diaz) who sets off on a journey east of the sun and west of the moon with a polar bear, whom she has discovered is actually a prince named Oskar (Jeff Goldblum) who had been cursed by his wicked stepmother (played by Helen Mirren). They hope to break Oskar’s curse. The decision to not follow Bluth’s original pitch would end up pleasing Katzenberg quite a bit as he believed that would help the film against Disney’s upcoming 1998 animated film, Heart of Ice. Universal’s film was also expected to release toe to toe against Bluth’s upcoming Beauty and the Beast film.

Unfortunately for East of the Sun and West of the Moon, it would that very three-way dueling film strategy Katzenberg wanted to run with that would ultimately doom the film itself. Despite some modest good reviews and praise towards the film’s cast (particularly Diaz and Mirren) and score by Han Zimmer, the film had the unfortunate luck of releasing a week before Disney’s biggest and most successful animated film since The Lion King, a massive unexpected success that could honestly be best compared to Universal’s own Heart and Soul film released two years before. Making just $62 million against a $75 million budget, East of the Sun and West of the Moon would experience a now infamous 82% drop on its third weekend as Heart of Ice began to completely sell out in theaters. Worse, the film had likely only avoided an even worse fate at the box office by the skin of its teeth due to Columbia and Michael Eisner moving Beauty and the Beast forward a whole month[3].

As Roger Ebert famously said when reviewing his favorite and least favorite films of the year, East of the Sun and West of the Moon had the unfortunate luck of being a good animated film that released between two of the greatest animated masterpieces of all time, one of them an animated box office titan.

Roger Ebert, who is particularly notable for liking East of the Sun and West of the Moon, put it as one of his favorite animated movies of the year 1998. (source: Pinterest)

In light of the film’s box office failure, the entire animation studio was unsurprisingly left scrambling and wondering what this would mean for the studio and how Katzenberg would respond, especially when the film’s failure could arguably be thrown at his own feet. Would their newfound independence be cut short? Would Katzenberg use the film’s failure to finally put an axe to the studio as he originally wanted?

They soon got their answer from Katzenberg when he announced there were going to be a small number of layoffs at the studio in order to cover the costs of the film’s failure. Those who had worked on EotSaWotM, like Grosvenor and Smith, would find themselves scapegoated for the film’s failure and bear the full brunt of the layoffs, with those that survived being merged into the team working on the studios upcoming City of Gold film. When confronted by Cohn over the layoffs, Katzenberg reportedly claimed that the removal of the animation team responsible for the film was in fact always planned by him[4]. This did little to sooth hurt feelings, as many at the animation studio were left with a bitter taste in their mouth and feeling angry at Jeffrey Katzenberg.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it wasn’t long before a number of caricature images from the animators mocking or attacking Katzenberg found themselves once more being passed around the studio. No doubt very much aware that the last thing the animation studio needed was Katzenberg catching wind of mocking him, Marjore Cohn was quick to try and put a stop to it. Yet this did little to put an end to the noticeable tension that was in the air as the studio turned to their next film, 1999’s City of Gold.

Basically, think our timeline’s Road to El Dorado + 1975’s The Man Who Would Be King and you'll get a pretty good idea for the story of City of Gold. (source: wikipedia.com)

City of Gold had technically been in production for a number of years, having actually been greenlit by Katzenberg after he had taken over. Katzenberg, as he later recalled, had been inspired by Hugh Thomas’s Conquest: Montezuma, Cortes and the Fall of Old Mexico and thought an animated film set in the Age of Discovery could work well. After the Universal merger, he would assign a small development team of animators made up of those who hadn’t been assigned to work on EotSaWotM, though for the most part production on the film trudged along slowly. It wasn’t until mid-1996 that production on the film would truly jumpstart, partially because Katzenberg wanted to find a particularly good screenwriter to work on the film.

At that point in time, Universal had only just started to fully embrace the recent animation practice of hiring a screenwriter to write the screenplay for an animated film, instead of the old traditional storyboard storytelling production style that was once the norm in animation. It had been a practice adopted by Disney a few years earlier and Katzenberg had fully embraced it for Spirit of the West, where he quickly found that he much preferred it over the older storyboard storytelling that was more commonly used during his time at Hollywood Animation.

Katzenberg, wanting to capture the adventurous and comedic tone found in Disney’s Aladdin, reportedly first approached the writing duo of Ted Elliot and Terry Rossio who had written the film Aladdin and asked them to come on board. Both said no, wanting to stay at Disney and ironically went on to write Disney's 1999 City of the Sun film, which would release the same year as City of Gold and lead to Katzenberg crying foul. With Elliot and Rossio spurring him, Katzenberg turned it over to Marjore Cohn, who in turn gave the task over to three relatively new writers named Philip LaZebnik, Jonathan Aibel and Glenn Berger[5].

Not longer after, the three presented Jeffrey Katzenberg and Marjore Cohn with a story treatment inspired partially by 1975’s The Man Who Would Be King, but set during the Age of Discovery and the lost city of El Dorado replacing Kāfiristān, which they would approve. The film’s story would follow an elderly former conquistador named Nicolás (who is based on Dravot), who recalls to a young Spanish adventurer named Tulio (who is clearly takes on Rudyard Kipling’s role in the story) of an adventure he had in his youth, were he and another conquistador named Diego (who is based on Carnehan) traveled to the Americas during the Age of Discovery and found the legendary city of gold, El Dorado. There they manage to be proclaimed as living gods by the natives after Nicolás survives an arrow unharmed (due to it being blocked by his cross necklace), and Nicolás is proclaimed King of El Dorado while Diego is proclaimed as his faithful servant. Taking advantage of the mistake, the two men decide to play along with it, helped along in their con by the beautiful Atzi, whom is betrothed by the natives to the newly crowned Nicolás but quickly discovers their deception. Soon, as the power begins to go to Nicolás’s head and Diego finds himself falling in love with Atzi, the two find themselves being viewed with suspicion by the High Priest Xiuhcoatl, who threatens to, and eventually does, expose their con.

Concept art for the film featuring Atzi, the native woman who helps the films main conquistador duo, as played by Rosie Perez. (source: characterdesignreferences.com)

Unlike 1975’s The Man Who Would Be King, the film would drastically differ in it’s ending. Here Nicolás survives, but takes on Carnehan’s role in that he is the one that loses everything and ends up being the one who meets with and shares his story with Tulio. Diego meanwhile also survives, but ends up staying with the natives and manages to replace Nicolás as King as well as goes on to marry Azti. Most critics would later regard the film having the natives still accept Diego and even going on to let him be their king after finding out he conned them, simply because of the two he was much kinder to them, to be a little forced if not outright a bit demeaning to the natives. The irony here of course is that it actually was forced on the writers, by Jeffrey Katzenberg no less.

For those unaware, LaZebnik, Aibel and Berger originally wanted to give the film a darker ending, which would have stuck closer to the ending of The Man Who Would Be King. In their original ending, Nicolás would have died like Dravot does in the 1975 film while Diego is the one who is forced to escape El Dorado alongside Azti, the later of whom who is implied to have died afterwards due to disease, which was originally going to be implied was slowly infecting the natives of El Dorado due to Nicolás and Diego spreading it to them. Now old, alone, and bitter, it would therefore be Diego who would go on to later meet with Tulio and try to discourage him from his desires for adventure by sharing his tragic story.

Katzenberg, however, reportedly didn’t like that intended ending, and considering this was late 1996/early 1997 when he still bothered to care about what Universal Animation was doing, he sadly forced them to change the film’s ending to what would be the final result we see today. Personally, I actually think the original intended ending sounded so much better, but oh well.

Regardless, production on the film would remain slow going for a number of months until the release of Spirit of the West, even as Andrew Adamson signed on to direct. It was only after the release of Spirit of the West that a number of animators involved in that film would move on to work on and complete City of Gold. By Late 1997, casting was already underway as Mel Gibson, Ray Romano, and Rosie Perez would each sign on to play the films three main characters Nicolás, Diego, and Atzi, while joining them would be Jeremy Irons as High Priest Xiuhcoatl and Grant Shaud as Tulio. Further hired to work on the film would be Han Zimmer, John Powell, and Matthew Wilder[6], who would each score and write music for the film.

Mel Gibson, Ray Romano, and Rosie Perez, the stars of Universal's City of Gold, circa 1999. (source: alamy.com; combined by @Nerdman3000 into one image)

Looking to avoid a repeat of the disastrous release of EotSaWotM, Cohn managed to convince a initially reluctant Katzenberg to put some distance from the release of Disney’s City of Gold at Thanksgiving 1999 release, City of the Sun, leading to the film eventually releasing on Memorial Day 1999, where it received mixed to positive reviews, with most complaints being labeled at the film’s ending and Rey Romano’s infamous and atrocious singing[7], even as praise was heaped on the film’s story (minus the ending, which some criticized as being needlessly happy), Jeremy Irons’ performance, and the film’s music. While the more mixed reviews did sting for Universal Animation, it was more than made up by the movie’s success at the box office, where it made an excellent $348 million worldwide. Further success was found upon its home video release, where it even managed to do decently in its home video release.

Still, with Universal having released an animation box office bomb followed by a more critically film mixed film, some in the industry as the new millennium began were left to wonder if the bad times would continue at Universal Animation and whether Katzenberg should tighten the leash that he had loosened on the studio, especially as Universal Animation geared to release two separate animated movies in 2000.

[1] Before ultimately deciding to go with Ruler of the Roost for Bluth’s third film at Columbia as part of his deal with Eisner, he originally had been hoping to resurrect East of the Sun and West of the Moon. Unfortunately, Hollywood/Universal Animation publicly announced their intention to adapt the story in question before Bluth did, forcing Bluth and go to go back to the drawing board.

[2] Part of me suspects that a lot of Bluth’s ideas here eventually went into Titan A.E. in our timeline.

[3] What makes this somewhat ironic is that after the move but before the release of Heart of Ice, Katzenberg would often privately mock Eisner and Bluth for having blinked. After the massive release of Heart of Ice, however, Katz convinced himself that Bluth and Eisner had somehow known what was going to happen and that they had in fact tricked him with the move.

[4] Since most of the animation team working on the film primarily belonged to those who had worked at Universal Animation before the merger with ABC and Hollywood Animation, this meant that the layoffs pretty much gutted most of the talent who worked at Universal before the merger. Things are a bit more complicated, since there are both truths and falsehoods here. Katzenberg’s original plan indeed was to have Cohn split the animation team that was working on EotSaWotM into three after the film’s release and have the animators simply join the three main teams that were working on City of Gold, Atlantis, and John Carter. No matter what, the animation team responsible for EotSaWotM was going to end. They weren’t however supposed to actually be laid off, like Katzenberg ultimately did.

[5] Elliot and Rossio in our timeline went to work on Road to El Dorado. Here they work on City of the Sun, leading Katzenberg to accuse them of stealing his idea. Philip LaZebnik in our timeline wrote the screenplay for Pocahontas, Mulan, and Prince of Egypt. The writing duo of Jonathan Aibel and Glenn Berger meanwhile wrote the Kung Fu Panda and Trolls movies in our timeline. The three will ultimately become a writing trio in this timeline.

[6] While Powell and Zimmer are the same as in our timeline’s Road to El Dorado, the inclusion of Matthew Wilder (who wrote the music for our timeline’s Mulan) is a new one. With Wilder on board, the film’s music ends up becoming much more well received and fondly remembered then the music from our timeline’s film.

[7] A bit of a joking nod here to the Ray Romano sings videos, which you can find on YouTube. Long story short, after Gibson decides to sing his parts in the film (similar to what he did in our timeline’s Disney's Pocahontas), Romano asks to also be allowed to sing his part rather than get someone to record over him. Most people afterwards agree it was a bad idea to let Romano sing (especially since his singing role in the film was more substantial than Gibson’s) and that it should have been dubbed over.

Personally, this take on Road to El Dorado sounds pretty good - Ray Romano singing aside.

And... I think I kind of prefer the ending that the film had, rather than the one that was proposed - it makes Nicolas and Diego more explicit foils (one 'let go' of that conquistador mindset and ended up with a happy ending, the other didn't and ended up old, alone and bitter). I also wonder if a lot of critics pointed out similar themes in Spirit of the West - by sparing Little Creek out of honour, Michaels' lieutenant (and, by extension, most of his men) symbolically "went native" in a similar manner to Diego here, whilst Michaels didn't and died.

(Might actually do a post on the Guest Thread about that).

And... I think I kind of prefer the ending that the film had, rather than the one that was proposed - it makes Nicolas and Diego more explicit foils (one 'let go' of that conquistador mindset and ended up with a happy ending, the other didn't and ended up old, alone and bitter). I also wonder if a lot of critics pointed out similar themes in Spirit of the West - by sparing Little Creek out of honour, Michaels' lieutenant (and, by extension, most of his men) symbolically "went native" in a similar manner to Diego here, whilst Michaels didn't and died.

(Might actually do a post on the Guest Thread about that).

Welp, that doesn't sound good for Atlantis. Looks like they'll start adapting children's books ahead of schedule...

Pretty much any industry dominated by mostly straight men is going to have a problem. Video games, films, journalism, comic books all have the problem. I've noticed that when tv shows tend to have female writers they're more willing to call out something sexist or awful. Some comments about Berserk I've read implied that while Kentaro Miura was never an outright sexist some of his earlier stuff fell into odd territory, and that meeting and befriending a female writer helped him improve his portrayal of women. Altered Carbon benefitted from having a female show runner.

Diversity and gender balance won't completely remove the problem but it will help.

In my experience, getting a bunch of young men in a room together drastically increases the likelihood of fart & boob jokes and inappropriate art, but it doesn't necessarily or even frequently devolve into true toxicity, none the less predation. Most guys do not want to hurt or humiliate women or exclude them (note the descriptions by Holiday et al about believing that most of the guys would be shocked to know that the women felt out of place). Of course leadership and example matter a lot. When the boss is slapping the women's backsides and talking down to them, this emboldens others to follow suit, and normalizes the behavior. This is where things can devolve into a hostile work environment very quickly if acts of predation and abuse are not stamped down quickly and unequivocally. And little is worse than the "do as we say, not as we do" attitude where you force the workers to watch bad '90s Sexual Harassment videos when the boss is openly feeling up his or her employees.I'd seriously disagree with that. Any industry where talent is perceived to be incredibly rare will have problems with culture. Because of the belief (real or not) that certain people cannot be replaced their bad behaviours will be tolerated, management will minimise or ignore complaints because they do not want to risk losing the 'star'. That will come out in different ways but the culture will always end up toxic.

Lasseter did not behave like he did because he was in a male environment, that was just who he was. He behaved that way because he got away with it and so pushed boundaries. Had management stamped on it earlier he may never have been a nice person to work with, but he'd have kept it professional for fear of being sacked. Or he had been an idiot and got sacked. Either way the problems would never have got so bad.

Now, when guys dominate and a "bro culture" sets in, even if its not predatory or toxic, it can still be an invisible barrier to entry. I read and hear plenty of accounts from women about not really being noticed unless you can "hang with the guys" and drink whisky and tell raunchy jokes (you see this a lot in the military), while shy "girly girls" (and frankly the shy, modest men too) get closed out of the loop, not necessarily by design.

The best bosses (e.g. Brenda Chapman, Brad Bird, and Glen Keane in animation, from what I've read) make sure that everyone feels empowered to speak up and that every voice is heard. This not only translates into a better work environment, it translates into a better product when the person who sees the obvious problem that nobody else does, but is afraid to make waves, is able to speak their mind and save the day. Bird in general related how one quiet girl in the corner had so many of the best ideas when she was able to express them, but until he made the effort to let her speak, she never did.

And that last bit speaks to what El Pip mentioned about "Any industry where talent is perceived to be incredibly rare" becoming more likely to shield or excuse bad behaviors. It falls into "great man theory" territory, and while individuals can be very talented, sometimes extremely gifted, it none the less is never One Lone Genius. Jim Henson revolutionized puppetry, but he did it by encouraging talented folks like Jane Henson, Frank Oz, and Jerry Juhl, and thus The Muppets didn't die with him. No single person created Toy Story. And when Lasseter was finally fired from Pixar, there were several extremely talented artists able to take over without quality suffering, e.g. Pete Docter, (Soul proved to me that Pixar is still the master of the medium). Meanwhile, others like Jorgen Klubien, who deserves far more credit than he received for sewing the seeds of what became Cars and The Frog Prince iOTL, left because of Lasseter's treatment and "idea theft", robbing Pixar of talent. Bird understood this very well, and made sure that his team was confident enough that if he left they could carry on without him.

Very true. My mother can tell horror stories about one female-run, female-dominated place that she used to work for.Eh, there’s nothing stopping a female-dominated workplace from being a toxic environment…

I can personally attest that one of the most abusive, hostile, toxic bosses that I ever had was female. Notably in a male-dominated environment, so that may have played a factor, but still, she was one of the worst I've ever seen, so absolutely no excuse. I don't tolerate that kind of behavior from male bosses either, and neither should you. Verbally abusive, vindictive, condescending, total lack of empathy, and even openly sexually harassed one of her employees...who was a preacher. Still, nothing much happened to her. Still in leadership positions. Every time I have to sit through the yearly sexual harassment and assault training I roll my eyes. Not like the leadership of the organization is policing its own ranks.

I certainly thought so. Thanks again to @Nerdman3000.Personally, this take on Road to El Dorado sounds pretty good - Ray Romano singing aside.

And... I think I kind of prefer the ending that the film had, rather than the one that was proposed - it makes Nicolas and Diego more explicit foils (one 'let go' of that conquistador mindset and ended up with a happy ending, the other didn't and ended up old, alone and bitter). I also wonder if a lot of critics pointed out similar themes in Spirit of the West - by sparing Little Creek out of honour, Michaels' lieutenant (and, by extension, most of his men) symbolically "went native" in a similar manner to Diego here, whilst Michaels didn't and died.

(Might actually do a post on the Guest Thread about that).