The fact that John Wilkes Booth failed in his attempt to assassinate Lincoln has unfortunately obscured the tragedy that he succeeded in his other stated goal – assassinating the two premier Union generals. Even as the nation celebrated the survival of its President, it wept for Reynolds, the commander of the Army of the Susquehanna, and Lyon, the General in-chief. With both Generals dead by Booth and his accomplices’ hands, the Union Army descended into disarray, as the main Federal force found itself without their commander, and even those who still had theirs were unable to effectuate the coordination and concentration needed to overcome the rebels. Booth’s actions thus changed the course of the war, as the carefully laid out plans for a victory in the summer of 1864 crumbled due to disorganization, probably prolonging the war for many months more. As the Northern diarist George Templeton Strong observed, Booth hadn’t just murdered three men. The blood of “thousands more” would be in his hands now that “the rebels, emboldened by this atrocity, fight with renewed vigor and a desire to imitate the bloodthirst of their beau”.

In truth, reactions in the Confederacy were far from unanimously in favor of Booth, at least initially. Moved by both honor, and fear that the assassinations had strengthened the Lincoln administration politically and internationally, Breckinridge was quick to disavowal any relation with Booth and his plans. That “madman” had acted on his own, the Confederate President asserted, “for no Southern man could for a second contemplate such dishonorable methods” even if, he added in a passage suggested by Davis, Lincoln “has no qualms with encouraging the murder of women and babes by fomenting domestic insurrections”. Southerners of the upper-crust were quick to echo Breckinridge, but merely because they feared that Booth had just foolishly stirred up Radical feelings in the North. In truth, most Confederates, including Breckinridge, seemed to somewhat justify Booth’s actions by adding that Lincoln and his acolytes were committing worse crimes every day. The Virginian Sallie Putnam claimed then that “the generosity native to Southern character” allowed them to condemn Booth, for “Reynolds and Lyon now dead were no longer regarded as enemies”, even if, in life “they had been implacable and unflinching in inflicting far worse suffering upon us”.

Putman’s words show that what at first had been an attempt to distance themselves from Booth’s actions soon became an outright justification of them under the argument that Lincoln was a much worse murderer. “The poor Booth is said to be a monster for killing three men”, Edmund Ruffin observed. But Reynolds and Lyon were “much worse vandals”, for they waged “a war of extermination” that had stained the soil of the South with the blood of thousands. Public repudiations of Booth were “shameful”, Ruffin concluded, saying that he should be hailed instead. The young Katherine Stone, exiled in Texas, indeed hailed him as the “brave destroyer” of two Generals that had “plotted and executed devastation, famine and desolation”. Stone was sorry to hear that Lincoln had survived; as for Booth, “many a true heart at the South weeps for his death”. Even the usually sober Mary Boykin Chesnut, who too called Booth a “madman” and worried that “these foul murders will bring upon us worse miseries”, considered the assassinations “a warning to tyrants and their pawns”. Lincoln should beware, for that “will not be the last attempt to put a President to death”.

Few believed Breckinridge’s professions of innocence, especially due to the “widespread approval of such atrocities coming out from Rebeldom”, as a Yankee officer remarked. When had Breckinridge ever shrunk from “cowardly assassinations, cruel punishments, bloody acts”, questioned a speaker in the Republican National Convention. Ask the men “massacred at Fort Pillow and Plymouth, cut to pieces in New York and Baltimore, executed in his gallows and dungeons” if the rebels were above such methods. For decades after the war, the “fact” that the assassinations were personally ordered by Breckinridge was accepted throughout the North, and it took a long time before passions cooled down enough for objective analysis to conclude that Booth had acted on his own. At the time, “hate rankled in the breasts” of all Union men, reported a soldier. “Oh, how strong is this passion, this desire for revenge”. The assassinations and the reactions of the rebels had filled the Yankees with the desperate conviction “that it is to be a war of extermination . . . Union men will have to kill as many secesh as they can before they kill us”.

Union propaganda depicting Booth being tempted by the Devil

Booth had perhaps bought some time for the Southern armies, but he had also unleashed a terrible vindictive spirit that made the last year of the war the bloodiest of them all. He had as well, just as Breckinridge had feared, strengthened Radical sentiments in the North. The greatest consequence was that the “rally round the flag” effect patched up the divisions in the Republican ranks, allowing for Lincoln’s renomination and the passing of the Radical amendment. In fact, the section providing for the direct trial of individuals by the Federal government was inspired by the actions of Booth and his crew. After it passed, the amendment was lambasted by Confederates as an “infamous document” that established a “centralized tyranny” and sought to “exterminate the White population of the South”. Lincoln had thus “at last unveiled his true objectives”, Breckinridge declared, and the knowledge that the enemy “will not rest until his vandal hordes have desecrated and polluted” all the South should impel the Confederate soldiers into “greater, braver, unfettered resistance”. The Rebels heard the message loud and clear, such as a Virginian who vowed to “massacre . . . the thieving hordes of Lincoln”, or a Georgian who said that in response Confederates should “burn! And slay! Until Ft. Pillow with all its fancied horrors shall appear as insignificant as a schoolboy’s tale”.

This defiance imbued some Yankees with the conviction that they, too, should fight with renewed vigor to finally defeat the Rebellion. But others were instead convinced that it was proof that the South could never be subdued by force of arms. Rather than a result of ideology, this possibility was informed by the disorder brought about by the assassinations and the corresponding slump in morale. Without Lyon, the Union found itself without a leader that coordinated all offensives to use the resources available to produce victories. The halo of martyrdom resulted in Lyon’s deficiencies as a General in-chief being forgotten for decades after the war – his tendency to just pressure commanders into hasty attacks when waiting could yield greater advantages, and his marked impatience that often had negative results. The disastrous Battle of Marietta is the clearest example of these flaws. Nonetheless, Lyon was a capable officer, with unquestionable patriotism and zeal, and a dynamic energy that put continuous pressure on the Confederates. The overcorrection of some historians who held that Lyon was a bad General in-chief or that Lincoln basically had to fulfill that position himself, is simply untrue. Consequently, the loss of Lyon was keenly felt, for without him the careful concentration of forces broke down as each commander put plans on operation, or stopped plans, without coordinating with his fellow officers.

The most affected of all Union Armies was, naturally, the Army of the Susquehanna, which had also lost its commanding officer, General Reynolds. Celebrated as a hero of the Republic due to his victory at Union Mills and his tragic death, Reynolds too has been the subject of revisionism and counter-revisionism that has made it hard to discern his qualities as a person and as a general. This started even before his funeral, as the Republican apparatus mobilized to paint Reynolds as a firm supporter of Lincoln and the Republican program. Reynolds’ distaste for Radicalism and politics as a whole, his initial reluctance to use Black troops, and his at-times contentious relation with Lincoln were all obscured. As with Lyon, there was some overcorrection later, especially regarding his military skills. Union Mills was painted as a fluke by historians who saw the Battles of Frederick, Mine Run, and North Anna as flat failures that showed that Reynolds was in truth a mediocre general. But in reality Reynolds imbued the Army of the Susquehanna with a drive, vision and spirit that it had lacked previously, keeping up the pressure on Lee and always making the rebel commander pay in every battle.

Most importantly, Reynolds had given stability and coherence to an Army that had been, before him, always submerged in petty squabbles and political conflict. Under McDowell, McClellan, and Hooker infighting had been endemic, as generals divided in cliques and subordinates conspired for their superiors’ posts. Indeed, McClellan had conspired against McDowell, and then Hooker against McClellan, all leading to a serious reduction in the Army’s capacities, as generals focused on their personal advancement rather than the cause. Lincoln unwittingly fostered this internecine culture, for both McClellan and Hooker had been rewarded by their conspiring by receiving overall command. In other words, Lincoln had inadvertently taught his generals that conspiring against each other paid dividends. Choosing Reynolds was a masterstroke, for he had the respect and love of the other commanders, and his single-minded focus on victory gave the Army of the Susquehanna a clear direction. Under Reynolds, the heretofore dysfunctional Army started to work again, with his presence being enough to prevent conflict and keep the rivalries at bay. But now that Reynolds was dead, strife was brewing again in the Army of the Susquehanna.

“If only he could see how his brave boys weep for him!” wrote Reynolds’ friend, General Meade, of the scenes at Reynolds’ funeral, which drew gigantic crowds as the coffin moved back towards his native Lancaster. But, Meade continued, “perhaps it’s better if he could not see us . . . he would be aghast at the villainy and baseness of these people!” The people Meade referred to was the other Corps commanders of the Army of the Susquehanna, who had not lost any time in bidding for the position of overall commander. In truth, Meade was being somewhat hypocritical, for he too had become involved in the game of military politics. Inevitably, with the Republican Convention and the Presidential election so close, Lincoln’s choice for a new commander of the Army of the Susquehanna and a new General in-chief would also be linked to electoral politics. As Von Clausewitz had observed, war was “the continuation of political intercourse with the addition of other means”, something especially true in a democratic society. Lincoln’s choice then would be inevitably political in nature, for he needed Generals that would help him accomplish his objectives and strengthen his position.

Strife within the command structure had worked against the Union several times

The most urgent choice was the commander of the Army of the Susquehanna. The main Union force could not be left without a leader, lest Lee seize the opportunity and inflict a crippling blow. In truth, the Army of Northern Virginia was not capable of going on the offensive, but this was still a welcome respite. Anxious of resuming the attack and hoping for a summer victory, Lincoln set to work on choosing a new commander. There were two main choices: Doubleday and Meade. The latter seemed the obvious one, for Meade had been a personal friend of Reynolds’, and close to him in military and political thinking. The former had the support of Radical Republicans, who liked Doubleday for being one of the few unabashed Republicans in the Army, always quick to pledge support to the causes of Black enlistment and suffrage, at least for veterans. Both were politically problematic, for War Chesnuts saw in Meade a possible candidate, and some Radicals thought that Doubleday, “the Hero of Union Mills”, could be a possible rival for Lincoln. Moreover, both men loathed each other, due to both differences in personality and generalship. Though the feud had started at the Battle of Frederick, it had remained under the surface thanks to Reynolds’ presence, but now it came to the forefront again as Doubleday and Meade bitterly laid the blame on each other for the Battle of North Anna.

The Army of the Susquehanna again threatened to divide into cliques as different generals supported different sides. Keeping in mind how the division between “Radical” and Conservative generals had negatively impacted the Peninsula Campaign, Lincoln scrambled for a compromise candidate that could, like Reynolds, keep the peace between the personalities and egos of the several commanders. Lincoln, reported John Hay, was greatly angered by this “incomprehensible” feud, which “makes me doubt whether I am awake or dreaming”. At the end, Lincoln decided to pick General Winfield Scott Hancock, a choice that both Meade and Doubleday found acceptable. The “very image of a romantic, dashing officer”, Hancock was a Pennsylvania Yankee who, similarly to Reynolds, had won his comrades’ affections thanks to his genial personality and his bravery in battle. Despite a lackluster career in West Point, where he graduated 18th in a class of 25, Hancock served well in the Mexican War under his namesake. Nonetheless, he first acquired notoriety during the Peninsula Campaign, where a pleased McClellan commented that “Hancock was superb today” after he led a successful counterattack. Nicknamed from the on, “Hancock the Superb”, the general seemed to be indeed an excellent choice due to his charisma and valor. Later events would however prove that Hancock was also imbued with superb shortcomings.

The choice for a new General in-chief was harder, not because of lack of candidates but because of politics. General Grant, who was a good commander and always loyally executed the government’s policies, seemed an obvious choice. In fact, Lincoln had even considered appointing him to command the Army of the Susquehanna. But Grant had resisted, expressing that “it would cause me more sadness than satisfaction to be ordered to the command of the Army of the Susquehanna”, both because of his attachment to the western armies and the known difficult politics and titanic egos of the Virginia front. Lincoln came to agree, observing that the Eastern soldiers wished for one of their own. “To spurn the whole of them . . . and substitute a new man would cause a shock, and be likely to lead to combinations and troubles greater than we now have”, the President commented. Nonetheless, Lincoln had come to believe that Grant was possessed of an extraordinary energy that his Virginia generals simply lacked. Lincoln’s greatest worry was not about Grant’s capacity, but rather his politics, for several politicians thought that Grant was a possible presidential candidate.

Grant himself claimed that he was “pulling no wires . . . I have no future ambition”. Yet Republicans like his friend Washburne saw in him a candidate that could defeat Lincoln; Chesnuts too thought they could woo him, given that Grant’s views were a cypher. As a result of these political concerns, Lincoln did not appoint a General in-chief for the rest of May, fearing that Grant had hidden political ambitions and that other generals would be unequal to the task. In the meantime, Grant set his sights in Mobile, decided to seize the important port after having spent several months setting up a campaign. At the start of the year, he had had his hopes dashed by the Lincoln administration’s focus on Texas and South Carolina, but Grant had managed to extract a promise of future support from Lyon. But now Grant worried that all his efforts would come to naught with Lyon out of the picture. In Philadelphia, Lincoln, who would have to be his own General in-chief for the moment, directed Admiral Farragut and General Banks to support Grant.

On May 29th, a Union fleet lead by Admiral Farragut approached Mobile Bay. With four Monitors leading the charge, alongside 14 wooden ships, Farragut boldly advanced towards the largest of the three forts that guarded the entrance to the bay. A pitched, terrific duel started, as the Confederate fort and vessels stroke back. The rebel flagship was the ironclad

CSS Tennessee, “the most redoubtable but also one of the most unwieldly ships afloat”. Tied to the mast of the Federal flagship, the

USS Hartford, in order to see over the smoke, Farragut observed as his ships tried to subdue the fort, navigating through the mined waters. A terrifying explosion then resounded, for the monitor

Tecumseh had hit a torpedo, being sent to the bottom alongside 90 Yankees. This lost seemed to sap the Federal momentum, but a decided Farragut, unwilling to retreat or surrender, then shouted “Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead!” Leading his flagship and the rest of the fleet unharmed through the minefield, Farragut proceeded to beat the Confederate fleet into submission. This included the

Tennessee, which after an attempt to ram the

Hartford that failed due to its slowness, was badly damaged and forced to surrender. Over the next three to four weeks, Farragut sieged and captured the rest of the forts, closing Mobile to blockade running and setting up the conditions for taking the city itself.

The Battle of Mobile Bay

Unfortunately for the Union, the Federal commanders on land were not as bold or as successful as Farragut was on sea. Having left a small contingent of soldiers in Texas, and a much larger garrison in New Orleans and its surrounding parishes, Banks set forth for Mobile. The plan, which he had discussed with both Grant and Lyon before the assassinations, was for Banks and Grant to link up, forming an unstoppable force that would take Mobile from land after Farragut had cut it off from the sea. But by the time Banks marched out of New Orleans, the situation had changed. The rebels, instead of waiting for their destruction, had decided to take the initiative. At least, some of them did. In the Georgia front, General Joe Johnston seemed to have a golden opportunity to follow up the victory at Marietta with a shattering blow against Thomas’ bluecoats that could drive the invader out of Georgia, and maybe even recover East Tennessee. The magnitude of the latest victory, “induces me to hope that you will soon be able to commence active operations against the enemy”, Breckinridge wired Johnston. But as was custom, Johnston demurred, again offering a list a lengthy list of problems, and concluding that “I can see no other mode of taking the offensive here.”

This remark caused consternation in Richmond, where Breckinridge surely felt a sense of déjà-vu. Indeed, Johnston had refused to move at the start of the year using the same reasons, and concluding that rather than taking the offensive he should retreat and wait for an opportunity to “beat the enemy when he advances, & then move forward”. Yet during the campaign Johnston had only retreated, and at the end the victory at Marietta was not because of Johnston, but in spite of him. At least, that’s what a tired Breckinridge believed. The President’s anger was increased as he realized that Johnston still had no intention to “move forward” even now that the enemy had been beaten back. At several emergency meetings, an incensed Jefferson Davis argued that the only way of “averting calamity” was by replacing Johnston. If he was allowed to remain in command, Davis argued, Johnston would just retreat again and possibly abandon Atlanta. But Breckinridge hesitated. Most civilians believed that Johnston was to thank for the victory, and the opposition press was lavishing praise upon him. As Mary Chesnut observed, “every honest man out west thought well of Joe Johnston” and were likely to side with him were he removed. Unwilling to face the backlash of the pro-Johnston public and press, Breckinridge maintained him in command, and tried to soothe his ego to earn his cooperation.

Johnston, however, remained too resentful of Breckinridge. The President had acted in an “unbecoming and insulting manner”, according to the General. By sending both Cleburne and Longstreet to Georgia, and allowing them to supersede Johnston, Breckinridge had “undermined my authority” and consigned him to a “powerless, humiliating position”. These bitter sentiments, expressed in “an ill-judged and foolish letter”, insulted Breckinridge. But the Confederate chief decided that a public showdown with Johnston would harm the cause too much. With admiration, William Preston Johnston praised Breckinridge for this forbearance, for being so “truthful and magnanimous. It was difficult to move him to anger, impossible to provoke him to revenge”. But those who read between the lines realized that the broken relation between the General and his Commander in-chief could hardly be mended. “The president detests Joe Johnston for all the trouble he has given him”, wrote Mary Chesnut “And General Joe returns the compliment with compound interest. His hatred of Johnny Breck amounts to a religion”. Under such circumstances, the hopes of effective cooperation were bleak, but Breckinridge still tried, suffering through Johnston’s “mind numbing” missives where he asked for his authority to be defined, and forwarding ideas for a campaign.

inadvertently, Breckinridge just added fuel to the fire, for several of the ideas Johnston received had come from Longstreet. The Virginian and his corps had remained in the Army of Tennessee, in the hopes of contributing to the next battle. More or less independent of Johnston, Longstreet was allowed to directly write to both Breckinridge and Secretary Davis, sharing both military plans and his impressions of the Army’s state. Compared with Johnston’s grim outlook, Longstreet’s reports painted a more positive picture, which, while recognizing a numerical and material inferiority, believed that the men could strike the Yankees. With both Cleburne and Longstreet there, Johnston would actually enjoy numerical parity, which meant, Longstreet declared, an opportunity to drive back Thomas. Longstreet’s energy pleased Breckinridge, who wrote back that they had to seize “the initiative with the greatest promptitude and energy”. Breckinridge believed the three generals ought to cooperate for the good of the cause, but this only compounded Johnston’s bitterness. Longstreet, in Johnston’s eyes, came to be “a snake” that was serving as Breckinridge’s spy and wanted to “usurp” Johnston’s command. No matter how much Breckinridge prodded, he was unable to get Johnston to cooperate actively with Longstreet.

The Army of Tennessee was both the least functional and less successful rebel army

After losing precious time by the feud, a tired Breckinridge finally gave up and ordered Longstreet to execute one of his plans, directing Johnston to reinforce Longstreet’s force by the addition of Polk’s corps. The plan was an advance against Knoxville, which if taken could threaten Chattanooga and force Thomas to divide his force. If successful, Breckinridge hoped, Longstreet could then be given overall command of the Army of Tennessee without raising too much of a controversy. The move caught the Federals off guard, for when Longstreet arrived at Bristol, Virginia, they had believed he was merely returning to the Army of Northern Virginia. Instead, Longstreet turned towards Knoxville, easily sweeping aside the outnumbered Union troops at the border between the states and capturing the supplies at Bean’s Station. Now, with enough food and ammunition to continue his march, Longstreet advanced through the open road to Knoxville. This was one of the events that changed the course of the Western campaigns, for the Union was forced to modify its plans to respond to this latest rebel threat. The other event was Grant being at last appointed General in-chief in early June, just a week previous to Longstreet’s maneuver.

Throughout May, Lincoln had anxiously sought to determine Grant’s political positions and loyalty. After all, as James McPherson observes, “Lincoln could scarcely work with a general-in-chief who wanted to become commander in chief”. Grant’s name continued to be touted as a presidential candidate, including by the influential

New York Herald. But Grant in truth had no desire to be a candidate, and he was loyal to Lincoln. To assuage him, the General sent several letters chastising his would-be backers and insisting that being President was “the last thing I desire. I would regard such a consummation unfortunate for myself if not for the country…. Nobody could induce me to think of being a presidential candidate, particularly so long as there is a possibility of having Mr. Lincoln reelected”. This open disavowal finally put Lincoln at ease. “You will never know how gratifying that is to me,” the President said after being shown the letter. “No man knows, when that presidential grub gets to gnawing at him, just how deep it will get until he has tried it; and I didn’t know but what there was one gnawing at Grant”. Just before the Republican Convention, Lincoln appointed Grant to the rank of Lieutenant General, the second after Reynolds, and summoned him to Philadelphia.

Despite arriving in the middle of the jubilee over the Convention, there was no one to receive Grant at the station. Grant, accompanied by his son Fred, walked to Willard’s Hotel. The clerk, “looking down his nose at the travel-worn, unimpressive figure in a dusty uniform”, replied that he only had a small room at the top of the floor. Unbothered, Grant simply signed the register, making the clerk almost fall over himself once he realized he had the famous U.S. Grant in front of him. Grant then went to a reception the Lincolns were hosting, appearing in his worm traveling uniform, for he had lost the key to his trunk. But the people ignored this faux pas, celebrating the arrival of “the hero of Donelson, Vicksburg and Liberty”, with cheers, handkerchiefs and by banging knives on tables. “Why, here is General Grant! Well, this is a great pleasure, I assure you!”, exclaimed the President when he recognized him. The poor shy Grant was then smothered by long throngs of people anxious to meet him. The next day, Grant officially received his commission as General in-chief, Lincoln promising that “As the country herein trusts you, so, under God, it will sustain you.” Knowing how unused Grant was to public speaking, Lincoln had the previous day shared a copy of his remarks to allow Grant to prepare an appropriate answer. A simple reply, it praised “the noble armies that have fought on so many fields for our common country”, and thanked Lincoln. Hardly a rousing speech, it was still interpreted by many as a ringing, direct endorsement of Lincoln, coming just a few days before the Convention. Indeed, a plan by Missouri Radicals to vote for Grant first was scrapped when they heard of the message.

The tall, lanky, and loquacious Lincoln, and the short, stout, and taciturn Grant, would develop a warm, mutually respectful relationship. The President had long admired Grant, for he was a fighter that, unlike other generals, loyally executed his policies instead of trying to resist them. He liked Grant because “he doesn’t worry and bother me. He isn’t shrieking for reinforcements all the time. He takes what troops we can safely give him . . . and does the best he can with what he has got”. As a general and a person, comments Ron Chernow, “Grant was the antithesis of everything Lincoln deplored in other generals—as eager to fight as they were reluctant; as self-reliant as they were dependent; as uncomplaining as they were petulant”. For his part, Grant came to genuinely love and admire Lincoln. “He was a great man, a very great man,” Grant recalled later. “The more I saw of him, the more this impressed me. He was incontestably the greatest man I ever knew”. Rewarding Lincoln’s confidence with concrete results and unswerving loyalty, Grant was at last the general Lincoln had been waiting for. Both men would forge a genuine friendship and an excellent working relation, becoming the team that would lead the Union to victory.

Not all shared Lincoln’s faith. Compared with Lyon’s aggressive zeal and Reynolds’ handsome, brave figure, Grant did not seem to be a fine example of a soldier. Many looked at him and found merely an unremarkable at best Western country bumpkin that had, as Richard Henry Dana Jr. sneered, “no gait, no station, no manner”. But it was in this “unpretentious but resolute demeanor” that others identified the key to Grant’s success. Though a “short, round-shouldered man” with “a slightly seedy look”, commented Philadelphia observers, Grant had “a clear blue eye” and “an expression as if he had determined to drive his head through a brick wall, and was about to do it”. Southerners too, saw in Grant a fearless foe who would finally use all the means at the North’s disposal to defeat them. “They say at last they have scared up a man who succeeds, and they expect him to remedy all that is gone wrong”, wrote Mary Chesnut. “So they have made their brutal Suwarrow, Grant, lieutenant-general”. More ominously, when he heard of Grant’s appointment, General Longstreet, once a friend that had even been his best man at his wedding to Julia, commented “That man will fight us

every day and every hour till the end of the war.”

That was precisely what Grant intended to do. After briefly considering retaining his headquarters in the West, Grant was convinced by Lincoln to move to Philadelphia. There, Grant started to fashion a new winning plan. Matching Reynolds and Lyon’ aggressiveness, Grant surpassed both slain commanders with his superb strategic thinking and willingness to engage in total war. The fragmented Union war effort was replaced with a comprehensive plan to use all the advantages of the North and completely devastate the Southern capacity to wage war. “Eastern and Western Armies were fighting independent battles,” remarked Grant, “working together like a balky team where no two ever pull together”. But with him a General in-chief, the Union Army would now pursue a policy of “desperate and continuous hard fighting”, that would push the rebels to the brink and keep up the continuous pressure until they broke. Using the Federal resources to their fullest, Grant planned to attack the Confederates on all sides, to prevent them from reinforcing each other and to deny them any rest. A delighted Lincoln, on hearing of the plan, remarked that this was like his “old suggestion so constantly made and as constantly neglected . . . to move at once upon the enemy’s whole line so as to bring into action to our advantage our great superiority in numbers.”

But before he could start Grant had to deal with Longstreet, whose campaign against Knoxville had started just after Grant’s appointment. Despite not having any time to settle in his new position, Grant did not disappoint, and with the dynamism that characterized him he set to work. Grant saw Longstreet’s advance not as a setback, but as an opportunity to catch and destroy him, inflicting a severe blow to both the Army of Tennessee and the Army of Northern Virginia. General Sherman, who had been given command of the Army of the Tennessee, was immediately ordered to turn north to East Tennessee, which could become “the scene of the next great battle”. Thomas, for his part, was to send one corps to Knoxville and use the rest of his Army to maintain the pressure on Johnston’s front, while Banks was ordered to continue his march to Mobile, which was only defended by an 8,000 men garrison whereas Banks had 26,000 bluecoats at his disposal. Grant sent a direct message to Sheridan, the commander of the reinforcements sent by Thomas, emphasizing that Knoxville had to be held and Longstreet could not be allowed to escape. The always enthusiastic Sheridan replied boastfully that he would not merely stop Longstreet, he would “thoroughly whip him”. The message endeared him to Grant, who said of the young General “I like the way Sheridan talks; it argues success”.

Through the next weeks Sheridan would back his confidence with deeds, fiercely pursuing Longstreet through East Tennessee’s forbidding terrain and delaying him with a series of skirmishes. Longstreet’s veterans were nonetheless able to reach Knoxville, but they were aware that Sherman’s main force was coming soon and were running low on supplies. The mountainous terrain proved too much for the strained Confederate logistics, and the country itself had been stripped bare by Thomas’ 1863 campaign. “Everywhere I look I find only desolation”, wrote a rebel soldier. “There are no civilians, no beasts, no farms in this land”. Knoxville itself had been strongly fortified, and Longstreet found that his map of the Confederate fortifications was seriously outdated. Firmly planted behind the new and improved Federal lines, Sheridan resisted Longstreet’s attacks. The Gray commander kept trying for two weeks until Sherman arrived. Now hopelessly outnumbered and facing destruction if defeated, Longstreet was quick to disengage and retreat, intending to return to Virginia.

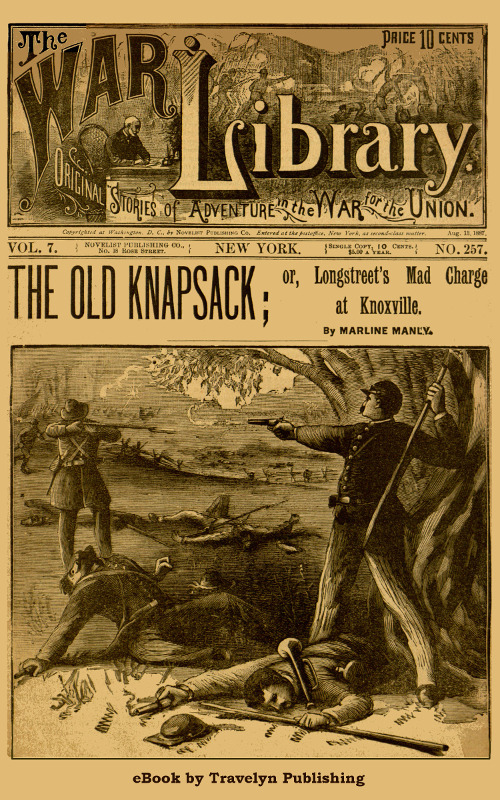

Magazine cover commenting on Longstreet's campaign

For Sherman, the area brought about only bad memories. It was in East Tennessee that he had failed at his first important assignment of the war, being branded a lunatic by the newspapers when he had failed to liberate the Unionist region. The memory of this bitter failure still gnawed at him, especially as he found the terrain just as forbidding as during his first campaign. Horses and mules starved and died by the wayside, and regiments advanced at a snail’s pace lest their men share the same fate. “East Tennessee is my horror”, the Federal commander said. “That any man should send a force into East Tennessee puzzles me.” Nonetheless, Sherman engaged in a prompt pursuit of Longstreet, catching him as he attempted to cross the Holston River. From behind hastily dug trenches, the rebels under Polk tried to resist an assault spearheaded by Sheridan. Alas, Polk fell by a sharpshooter, and a section of the Confederate trenches was captured. The Union success was then stopped by a counterattack led by John Bell Hood, which forced Sheridan back and secured the important bridge over the river. The rebels then managed to slip away, the entire battle only raking up relatively the minor casualties of 1,500 men on both sides.

Over the next days the terrain proved to be the greater foe of both sides, as Sherman was unable to continue his pursue due to the terrible logistical situation, but observed as the roads were clogged with the corpses of Longstreet’s own draft animals. The attempt to catch Longstreet had failed, and after destroying a few bridges to prevent a second expedition against Knoxville, Sherman retreated. In Philadelphia, although there was some disappointment at the fact that Longstreet had managed to slip into Virginia, Banks’ own failures caused greater consternation. Indeed, despite his superior numbers, Banks’ Army was bogged down before the fortifications of Mobile, trying to completely encircle the garrison instead of assaulting the weaker eastern defenses as Sherman had advised. Banks thus lost an opportunity to secure the surrender of the city before Cleburne returned. When Cleburne finally left the Army of Tennessee, disgusted at Johnston’s failure to do anything, he found that Banks had divided his Army, and easily struck the separated wings. A panicked Banks immediately evacuated to the sea, failing in his assignment and giving Southerners a morale boost.

Though Breckinridge shared the pride over the successful defense of Mobile, he was aghast at Johnston’s inaction. He had expected the General to use Longstreet’s campaign as a distraction to hit and drive Thomas back. Given that Sherman had went to support Sheridan, the Army of the Cumberland wasn’t as weakened as Breckinridge hoped, but it still had lost a corps and one of its more talented and aggressive commanders. Telegrams and letters continuously arrived to Johnston’s headquarters, prodding him into action and asking for his future plans. But Johnston answered to all these enquires by simply saying that an offensive was “impracticable”. Attempts by other generals to convince him to go on the attack only seemed to anger him. Colonel Henry Brewster, reported Mary Chesnut, was openly saying that “Longstreet and Cheatham wanted to fight,” but Johnston “resisted their counsel” because he was “afraid to risk a battle”. Assistant Secretary of War Seddon arrived at the same conclusion: “Johnston’s theory of war seemed to be never to fight unless strong enough certainly to overwhelm your enemy, and under all circumstances merely to continue to elude him”.

The straw that broke the camel’s back came in July, when Longstreet and Cleburne had both left Georgia. The opportunity for attack had passed, Breckinridge pointed out, so now they would have to play defense. “I wish to hear from you as to present situation & your plan of operations”, he wired, and was dismayed by Johnston’s reply. “As the enemy has double our numbers”, Johnston explained, “we must be on the defensive. My plan of operations must therefore depend upon that of the enemy. . . . We are trying to put Atlanta in a condition to be held for a day or two by the Georgia militia, that army movements may be freer and wider”. This made it apparent that Johnston was not going to seize the initiative, and that he might even yield Atlanta to the enemy. “We have given Gnl Johnston too many opportunities”, concluded Breckinridge. With the unanimous support of the cabinet, Johnston was removed as commander of the Army of Tennessee and replaced with Franklin Cheatham. To replace the fallen Polk, for whom the President shed few tears, Hood was ascended to corps commander.

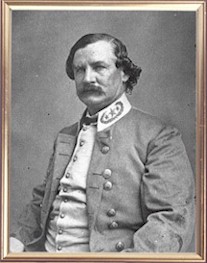

Benjamin Franklin Cheatham

On the Union side, Grant also hoped to make changes in command. When it came to strategy, Lincoln assured Grant “that he had never professed to be a military man or to know how campaigns should be conducted, and never wanted to interfere in them.” If he had meddled, it was merely because of the “procrastination on the part of commanders”, but Lincoln had in truth always wanted “some one who would take the responsibility and

act”. Lincoln “greatly overstated the degree of his future detachment”, comments Chernow, but the President did offer Grant his full support and a great deal of strategic and tactical liberty. Still, despite this seeming hands-off approach, Lincoln did instill into Grant the need to focus on Lee’s Army and to maintain and expand the government’s policies, chiefly Emancipation, the use of Black soldiers, and land redistribution. Due to Lincoln’s careful influence, Grant decided against his first plan, which entailed “an abandonment of all previously attempted lines to Richmond” followed by roundabout attacks. Instead, he was going to take the fight directly to Lee, Johnston, and Cleburne. “It was a tribute to Lincoln’s skill in managing men that, even while giving the general these assurances of independence, he succeeded in reshaping Grant’s strategy”, says David H. Donald, “and that his tact and diplomacy permitted the general to think that he was conducting the war with a free hand.”

Even as they came to agree on strategy, unfortunately for Grant, Lincoln’s political objectives prevented the new General in-chief from carrying out some of the changes he wanted. The main one consisted in getting rid of the political generals who had so often bungled their tasks. Grant soon learned that sometimes political power trumped military competence. And so, Butler was retained in command of Union forces in Maryland because of his popularity with Radicals, and Franz Siegel remained in the Valley even though he had failed there many times already, because he was a favorite of German Republicans. Both were blocs that Lincoln was weak with, and whose support he would need for his reelection. Banks, who irritated Grant by fumbling the campaign against Mobile, would also remain in his post because despite his military incompetency he was a powerful political player and a key ally for Lincoln in Louisiana. The continued presence of these political generals in important commands would create further headaches for Grant. They “were the bane of his life, a special curse on the Union cause”, declares Ron Chernow.

Despite this difficulty, people were quick to recognize that the Union war effort was now endowed of a greater energy and clearer purpose than ever before. Orders were sent for Thomas to advance against the Army of Tennessee, now under Cheatham’s command, and to take Atlanta. Sherman was tasked with sweeping through the South down to Mobile, putting down the breadbasket region of Black Prairie under a firm Union control, before striking against Cleburne and taking Mobile. Hancock and the Army of the Susquehanna would be the fulcrum of the effort, engaging Lee in direct battle, driving him back to Richmond and seeking to destroy his Army. Banks and Siegel for their part were ordered to advance in secondary attacks against Mobile and the Shenandoah Valley, respectively, to prevent the rebels from shifting troops from one theater to another and to aid the main Armies in their campaigns. Altogether, these plans augured a great, concerted assault on the Confederacy during the summer. “Oh, yes! I see that,” Lincoln exclaimed as Grant explained his strategy. “As we say out West, if a man can’t skin he must hold a leg while somebody else does.”

Just before the start of the campaign, Grant visited the Army of the Susquehanna. General Reynolds had always been received with cheers, shouts and hats flung into the air. But Grant never inspired “the adulation or hero worship that Little Mac and Reynolds had so easily called forth . . . They reacted with respect, not rapturous cheers”, relates Chernow. Charles A. Dana, when he visited Grant in the West, had observed how his soldiers appreciated Grant’s humility. The soldiers “seem to look upon him as a friendly partner of theirs, not as an arbitrary commander.” When he rode by, instead of cheers they would "greet him as they would address one of their neighbors at home. 'Good morning, General,' Pleasant day, General,' and like expressions are the greetings he meets everywhere. . . . There was no nonsense, no sentiment; only a plain business man of the republic”. In time, Grant would come to earn similar respect and appreciation from the Army of the Susquehanna, but at the moment many of the Eastern men were unimpressed with, or plain resentful of his presence. “The feeling about Grant is peculiar”, commented Charles Francis Adams Jr., “a little jealousy, a little dislike, a little envy, a little want of confidence.”

All these mixed feelings were in evidence during Grant’s first meeting with Hancock. Privately, Grant thought someone else should be in command, but, he observed, “I have just come from the West and if I removed a deserving Eastern man from the position of army commander, my motives might be misunderstood, and the effect be bad upon the spirits of the troops.” For his part Hancock was decided to maintain his independence. He balked at Grant’s initial plan to move his headquarters to the field, noting that Lyon never hovered above Reynolds’ shoulder like Grant proposed to do. In Hancock’s view, he had been tasked with upholding Reynolds’ legacy and finishing his work – for the victory to be truly the Army of the Susquehanna’s, it had to be allowed to fight by itself instead of under the direction of an outsider. For the moment, Grant accepted to only issue broad strategic orders, giving Hancock liberty to decide on the details and the precise tactics, both to achieve a working relationship and because Grant was needed at Philadelphia to coordinate the other offensives. Though unorthodox, this agreement seemed fine enough for the time being, and helped to conciliate the officers of the Army. “I was much pleased with Grant,” Meade at least concluded in a letter to his wife. “You may rest assured he is not an ordinary man.”

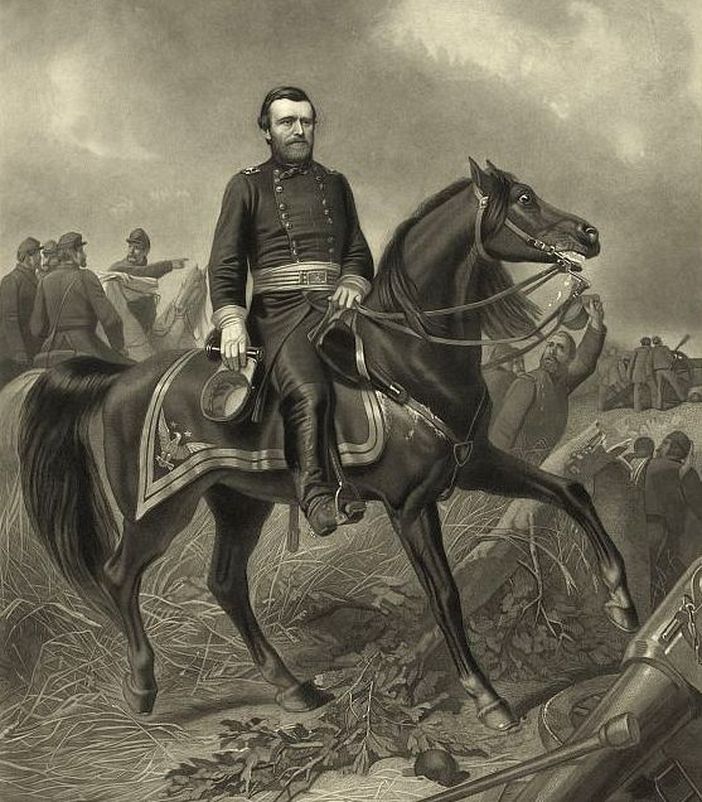

Grant taking command of the Union war effort

As the armies of the Union started to marshal under Grant’s direction, hopes and anxieties started to bloom within the Northern people. These were “fearfully critical, anxious days,” wrote George Templeton Strong. The campaigns, he continued, would decide “the destinies of the continent for centuries” to come. In Philadelphia a “painful suspense” that “almost unfits the mind for mental activity”, reigned, as the President waited for the military movements to start. But Grant’s decisiveness and capacity had alleviated Lincoln’s cares at least somewhat. “Grant is the first general I’ve had! He’s a general!”, he exclaimed when William O. Stoddard questioned if Grant would be capable of finally achieving victory. “He hasn’t told me what his plans are. I don’t know, and I don’t want to know. I’m glad to find a man who can go ahead without me.” Just before Sherman, Thomas, and Hancock were scheduled to move against their foes, Grant visited Lincoln. “Whatever happens, there will be no turning back”, he assured his Commander in-chief. “I propose to fight it out if it takes all summer”. This final line immediately captured the imagination of the Northern public, which noted in it a confidence and firm resolve that inspired them like never before. “The North had broken loose with a tremendous demonstration of joy”, wrote Noah Brooks. “Everybody seemed to think that the war was coming to an end right away.” This enthusiasm and energy would be put to the test in July, 1864, as the Union started the campaigns that would decide once and for all the results of the election and of the war itself.