I agree with you and as ever, there is a method to my madness having Prince George push for a marriage with Franziska which will have important ramifications later on.I hope he does push ahead with it, actually. If he does, and the world doesn't fall in, we might not have a Princess Margaret/Peter Townsend or a Charles and Diana analogue in this universe, which can only be a good thing... As much as I admire the Royal Family, they handled those couples appallingly. Margaret should have married Townsend and Charles Camilla from day one...

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Crown Imperial: An Alt British Monarchy

- Thread starter Opo

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 131 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

GV: Part Four, Chapter Five: Looking Away GV: Part Four, Chapter Six: Brothers and Sisters GV: Part Four, Chapter Seven: Mothers and Sisters GV: Part Four, Chapter Eight: An Answer to Prayer GV: Part Four, Chapter Nine: Kings and Successions GV: Part Four, Chapter Ten: Cat and Mouse GV: Part Four: Chapter Eleven: Secrets and Lies GV: Part Four, Chapter Twelve: Life at LissonHurray!I agree with you and as ever, there is a method to my madness having Prince George push for a marriage with Franziska which will have important ramifications later on.

Great chapter! George Cambridge and his stupidity strikes again! I guess this situation has now confirmed Prince George as the “bad boy prince”. Also, congratulations on 1000 replies!

Last edited:

GV: Part Three, Chapter Seven: Decisions, Decisions

King George V

Part Three, Chapter Seven: Decisions, Decisions

Part Three, Chapter Seven: Decisions, Decisions

Though the British Royal Family braced themselves for a mass outpouring of public displeasure and a prolonged scandal in the wake of Prince George of Cambridge’s shocking decision to marry a low-born Roman Catholic Hanoverian, the expected tirade of opposition failed to materialise beyond those who were perhaps best described as professionally outraged. That is not to say that when the story did break, people were not taken aback by it. “Prince George of Cambridge to Wed Catholic” was a shocking headline for the time but as the Palace remained tight lipped on the King’s response to the forthcoming nuptials, newspapers were forced instead to print speculation. This was accompanied by a series of opinion pieces written by middle-class snobs who took an almost funereal tone, proffering such morbid observations as “there will be great sadness at the news that a young man of such excellent parentage, so wonderfully raised with tradition and duty as his guide, should become a fallen Prince condemned to so tragic a future”. The Bishop of Durham provided a bizarre commentary in which he did not mention the Prince directly but instead, suggested that “the radical element in society which seeks to impose a decline in moral standards will no doubt rejoice as their wicked ways singe the institution of marriage, just as their evil followers set a torch to the factories and mills of the North”. The aristocracy were suitably outraged and delighted in equal measure. Public face demanded their opposition to the match but their dinner parties were certainly made more interesting as guests swapped the latest rumour and gossip they had picked up from an erstwhile lady in waiting or retired equerry.

Politicians too were obliged to pass some comment, though as the Prince had not yet married and taken himself out of the line of succession to the British throne, few were willing to comment publicly. Though some could not help themselves and in the House of Lords, the Earl of Winchelsea made a passionate declaration of support for the King for his “demonstration of the sincerity of the vow His Majesty made to uphold the Protestant succession”, whilst Lord Melville was heard to remark that if his son (Henry Dundas) ever behaved in such a way as to humiliate his parents and his regiment, he should waste no time in “horse whipping the boy until he was corrected”. But if the establishment expected a mob baying for blood outside Cambridge House in Piccadilly, there were much mistaken. Though the Palace prepared a statement reassuring the public that the marriage would not be recognised and that, if it was contracted, the King had pledged to remove royal rank from his cousin, the need for it never arose. In reality, the working classes were simply too hungry to give a damn as to whom a minor British princeling had taken for his bride some 600 miles away and those who otherwise might find time to criticise were trying to find a way to stop their empty factories, mills and mines from becoming abandoned concerns.

An engraving of a "typical" Chartist demonstration, 1842.

By September 1842, the strikes borne of the Baring Cut had spread beyond the factories and mills of the north to the mines of the Midlands and even as far as the docks at Dundee. When industrial action reached a new town or city, the loudest agitators were quickly arrested and the crowds read the Riot Act before being forcibly dispersed. Ringleaders were put on trial for offences of varying severity; any charge would do so long as it got them off the streets and into gaol. But the fact remained that many were still refusing to return to work until their wages were restored and this time, they were prepared to stand firm in this demand regardless of anything the police or the local militia might throw at them. The official line taken by the government was that the strikes were a disproportionate response but in private, many members of the Cabinet blamed Baring for a failure to predict the consequences of reintroducing of the income tax which saw industrialists slash wages to offset the rise in their rates. The government could not force employers to restore wages, neither could they afford (economically or politically) to u-turn and scrap the income tax once more even though Baring’s catalyst for its reintroduction had been resolved. The war in China had been won and the peace talks at Nanking were to see a push for a profitable territory grab that would re-open trade routes and secure hefty reparations from the Qing. But most knew that this was only a sticking plaster on a gaping wound. The war had not plunged Britain into economic decline; the combined policies of successive governments of the last 50 years had contributed to that and increased shipments of tea were hardly like to turn the tide.

From 1840 until 1842, the Tory government had been fortunate in that they faced no real opposition. Their official majority was boosted by like-minded Unionists who, though they sat on the opposition benches, more often than not leant their votes to government bills. Lord Cottenham’s departure from office and the Whig defeat in the last general election had left the Whigs divided and bruised and as they struggled to find a new sense of purpose (not to mention unity), the Tories were able to ride out the storms of the day without worrying too much about their electoral rivals. But in September 1842, all that changed. The horse trading of the summer at Holland House and Bloomsbury Square had seen a clear victor emerge from the two front runners in the race to lead the Whig party to restored good fortune. That victor was the former Foreign Secretary, Lord Melbury. But unlike his predecessors, Melbury was not frightened, or even resentful, of his rival Lord John Russell. Indeed, though he had captured the support of the Spencerites and swung the Whig party to his corner, Melbury was wise enough to know that he could never lead the Whigs successfully if he did not acknowledge the Russell Group and try to bring them on board as he set sail for a new political course. To effect this, he would have to welcome Russell and adopt some of his positions. What emerged was an effective double act with Melbury finally able to take the Tories to task in the Lords with Lord John tackling the government in the Commons [1]. For those on the Tory benches who had delighted in Whig division for so long, they were about to reap what they had sown. The strikes of 1842 brought the Whigs together for the first time in two years, allowing them to focus on an issue they could all rally behind. The same could not be said for the government.

The strikes of 1842 were markedly different from anything the United Kingdom had seen before in that they were organised and mostly non-violent, which made policing those who picketed or withdrew their labours increasingly difficult. Indeed, even the most experienced magistrates could not find a way to punish a man for refusing to work for a wage he did not feel fair, though many were helped along by law enforcement who were not averse to embroidering a charge sheet or putting strikers at the scenes of other crimes to get a conviction. Naturally this served to agitate the strikers even more and within weeks, many town gaols were full and the crowds in the streets were still so large that they could not be broken up in sufficient numbers to clear them completely. Where stragglers remained, reinforcements seem to appear and within hours, market towns and city suburbs were just as full as they had been earlier that same day. Such was the benefit of co-ordinated strike action.

Around this time, the Prime Minister travelled to Buckingham Palace for a private audience with the King. George V had been following developments where the strikes were concerned and he had serious worries that there seemed to be a distinct lack of urgency in the government's response. After exchanging pleasantries, the King and the Prime Minister sat in the King’s Study where Sir James began to work his way through the latest reports; 4 killed in Norwich, 18 arrested in Lincoln, 34 gaoled in Manchester, 2 factories burned out in Leeds. What had begun as a handful of non-violent strikes in major cities seemed to be spiralling out of control fast and yet Sir James Graham read this catalogue of social unrest as if it were a weary church bulletin.

“Moving on to Hong Kong…”

“Hong Kong?”

“Yes Your Majesty”, the Prime Minister said vaguely, “The peace talks, you know. I am informed they will conclude in a few days’ time, we have now successfully added treaty ports at Amoy and a place called Foochow…that brings the total amount to four and that is of course, in addition to the port authorities we have secured at Canton…”

“Oh”, the King replied somewhat puzzled, “Well…yes, that’s very good. No, Prime Minister, I thought we might stick with these strikes for a little while longer”

“We may have to Sir”, Sir James laughed, "I fear the working classes have begun to regard the situation as a prolonged public holiday which they are not eager to see end any time soon"

The King smiled awkwardly. What on earth was so amusing?

“Prime Minister”, he began, leaning forward earnestly, “I must confess that when I read that report, with the news from Lincoln and Manchester, I had not realised quite how serious the situation had become. I know I have some catching up to do but…well…I am quite alarmed at what appears to be a growing move to disorder”

Sir James put down his papers and clasped his hands before him as if he were about to lead the King in a prayer. His tone was suitably sanctimonious.

“Fear not Sir”, he said, “I am assured that the taste for prolonged strike action is waning. In Hull there is a general return to work already, and for quite a small increase in wages, we expect other employers to follow suit in the coming days”

“But what is their incentive to do so?”

“They will starve if they do not Your Majesty”

“Not the strikers. The employers…”

It was the Prime Minister’s turn to appear puzzled.

“The employers Sir? It is not the business of government to regulate what an employer should pay a man for his labours. I am disappointed at some who chose to offset the increase in their rates by cutting wages but nothing could justify my intervention in the way a man wishes to operate his own concern, whether that be factory, mill or…if you will forgive me Sir…palace. You see Your Majesty, it would be akin to my passing a bill which forced the Crown to pay its farm labourers a certain wage regardless of their productivity, length of service, ability even. It cannot be done Sir. And soon enough, the strikers will realise that and they shall have to return to work. It may take a shilling or two more on the part of the employers to convince them to do so, but there is simply no alternative”

“But these Chartists…”

“The Chartists are a radical mob taking advantage of the poor and feeble-brained”, the Prime Minister said haughtily, “They are using this unfortunate business for their own ends and I concede they are enjoying some success in it. But they cannot feed the masses Your Majesty. Only work can do that”.

The King stood up but motioned for the Prime Minister to remain seated. As he paced, he took in Sir James’ words. They may well reflect the reality of the situation but they still rang of cold indifference to the plight of many.

“So is your decision to ride out this wave of strikes, Prime Minister?”

“Yes Sir”, Graham replied, almost sighing, “The Chancellor informs me that the economic situation shall improve in the short term and when it does, we shall be able to abolish the income tax once more and employers shall have better means to increase the wages available to their employees. Patience and perseverance made a Bishop of His Reverence, what? Now....the talks at Nanking...”

The King gave another weak smile as the Prime Minister returned to his papers. There was more detail about the cessation of Chinese territory, a list of recommendations for a new Governor to be appointed at Hong Kong and then a schedule for a proposed state visit from the King of Prussia. He said nothing and waited for the audience to conclude. The Prime Minister left the King’s study that evening and heaved a sigh of relief. In truth, he did not believe a word of what he had just said. Baring’s decision to reintroduce income tax only received the approval of the Cabinet as a whole because it would be a temporary measure to provide the Treasury with a buffer. Whilst it was true that the peace talks in Nanking would see trade routes re-open (thus slashing prices on goods such as tea) and whilst the Qing had indicated that they would indeed pay a hefty sum in war reparations (the figure of £25m had been proposed), Baring was mistaken if he believed that it was the nation’s military adventures alone which had brought Britain to the brink of a recession [2]. The problem was the government could not force employers to reverse wage cuts (that much the Prime Minister had been honest about) but neither could it afford (financially or politically) to u-turn on the income tax.

At a Cabinet meeting held shortly before the Prime Minister’s trip to Buckingham Palace, it was obvious that the King was not alone in his concerns. At a meeting held in London, Chartist leaders William Lovett and Henry Vincent were calling for a general strike in which all working men would show solidarity with those affected by the Baring Cut in withdrawing their labour for two days, thus bringing the country to a standstill [3]. The Prime Minister knew only too well that these were overly ambitious goals, the vast majority of the working poor could not afford politics and nobody was going to lay down their tools when they desperately needed work. In the larger cities, most employers had overcome the difficulties of the strikes because for as many who were prepared to take industrial action, there were ten men only too eager to take their place for a lower wage because they had no choice but to work if they hoped to feed their families. That said, the Chartist threat was not going away any time soon and now the Home Office was coming under just as much pressure as the Treasury as demands came from magistrates for more powers to restrict freedom of assembly as Lord Liverpool’s government had done some 25 years earlier in the face of increased public unrest. The Home Secretary was refusing to consider such a move. Gladstone believed Liverpool’s “Six Acts” to be “the worst kind of repression a government could ever impose” and told the Prime Minister that he would rather resign than “commit to an act which will do nothing but inflame tensions and lead to greater civil unrest”. [4]

Gladstone in 1838.

This put Gladstone at odds with his Cabinet colleagues. Lord Wharncliffe, Lord Lowther and the Duke of Buccleuch all agreed that emergency legislation was needed to prevent strike action spilling over into something far more dangerous - if it hadn't already - and when Gladstone firmly rejected such a notion, they made it their common goal to see him ousted from the government. Gladstone might well have expected this. His appointment as Home Secretary in 1841 had not been entirely popular at the time and he was minded to turn down the offer of the post because he felt he may find himself quickly at odds with more traditional Tory voices such as Lowther and Buccleuch. The Prime Minister was discouraged from giving Gladstone the post in the first place by none other than the outgoing Home Secretary, Sir Robert Peel. Peel had been pleased to have the opportunity extended to him to redeem his reputation somewhat following the 1838 general election defeat which saw the Tories beaten back into continued opposition by Lord Melbourne. But many in Graham’s Cabinet disliked Peel just as much as they did Gladstone and it quickly became clear that his position was untenable. When he resigned, Graham suggested to Peel that he may promote the Leader of the House of Commons, William Gladstone, to Home Secretary. Peel could only foresee that Gladstone would find the same reception in office and urged Graham to choose someone else. But the Prime Minister had an ulterior motive for promoting Gladstone. [5]

William Gladstone had made a name for himself in the 1830s on two major political issues of the day; slavery and the Corn Laws. On the former, he allowed himself to be dominated by his family’s interests in the slave trade and fought hard against its abolition, even going so far as to personally secure compensation for his family concern to the tune of £105,000. This put him firmly among the ranks of the “High Tories” who were of like mind, many of whom had since left the party to join the Unionists. Yet Gladstone was a complex man and when it came to the Corn Laws, he set himself amongst quite another group who had nothing in common with the anti-abolitionists. At first, much like the Prime Minister himself, Gladstone had been a keen supporter of the Corn Laws which regulated the price of imported grain. But, again much like the Prime Minister, in recent years he had mellowed in his attitude and had begun to consider that they were doing more harm than good. He even allowed himself to attend Anti Corn Law League meetings at Exeter Hall, though he was never a member and thought the League far too radical in its position. But men like Wharncliffe, Lowther and Buccleuch were keen supporters of retaining the Corn Laws and when Gladstone innocently remarked in Cabinet that the income tax would never have been needed had the government addressed the Corn Laws first, this kick started their campaign to have him removed [6].

Sir James Graham appointed Gladstone because he knew that he had the potential to be a great rival. In Cabinet, Gladstone would be bound by the convention of collective responsibility but his wide scope of interests would also be restricted to just one portfolio. Better Gladstone on the frontbench, calm and controlled, than Gladstone on the backbenches, free to raise merry hell. Gladstone saw off some of his critics earlier in 1842 when he privately indicated his opposition to reintroducing income tax (though he ultimately agreed on the basis that it would be a temporary charge) but he flung himself firmly back into their firing line when, faced with general strike action, he suggested that the government “seize the day” and at least consider a move to reform the Corn Laws in line with some of the Prime Minister's own writings on the subject. To do so would take the wind out of the Whig sails, reduce prices, and remove the motivation for the strikes. Whilst he was still lukewarm to a wholesale repeal, the circumstances of the day led him to believe that something must give if the government was to continue to rule out a u-turn on income tax reintroduction. Wharncliffe jumped on this statement and asked rudely, “Why do you not concern yourself less with the Treasury and more with your own department Gladstone? Your refusal to counter appropriate restrictions of public assembly is making the situation worse by the hour, your priority should surely be that? Leave the accounts to Baring”.

Sir James Graham shot Wharncliffe a disapproving glance.

“That isn’t very helpful...”

“But it is true”, Lowther chipped in, “In the name of God man, there’s riots on the streets and there have been no steps taken to prevent further bloodshed. We must act now to protect the general public from the mob!”

“The general public are the mob”, Gladstone snapped, “If you wish to put it that way. If you restrict their liberty you shall only give the Chartists the justification they seek to continue this madness”

“Quite right”, Baring replied in agreement, “Agitators are one thing but the common man will return to work when his belly is empty, you do not need to arrest him to bring him to heel. That will happen naturally”

“That isn’t quite what I meant…”, Gladstone sighed, “Gentlemen, the fact is that a man has the right to speak his mind and to protest his view. He does not have the right to cause violence to his neighbour or destroy public property but these men are, on the whole, not inclined to such activity. They have simply withdrawn their labour and I cannot, we cannot, pass a bill that forces them to take up their tools again against their conscience”

“Balderdash!”, came a shout from across the table, “We have a responsibility to act in the common good!”

“It is a duty”, another minister cried out in protest, “A Christian duty to protect them from evil influences!”

"Evil?!", someone else bellowed, "The working man is not evil Sir, it is the radicals who poison him...!"

Sir James Graham wrapped his knuckles loudly on the table. Silence descended.

“Gentlemen, please”, he said sharply, “I fear we are proving our opponents correct in their assertions that we are a divided group. Let me say, here and now, that I do not intend to revisit the Corn Laws at this moment. Neither do I intend to reimpose the Six Acts passed during the tenure of the late Lord Liverpool. We have a solution staring us in the face and it is one we can pursue without recourse to petty arguments at this table - and I believe, which will cause minimum fuss with maximum results. When the income tax proposal came before us, we agreed that it’s reintroduction should be temporary. Therefore, I believe we should announce a timetable for phasing it out with minor decreases to the rates as the deadline for its removal draws near. I have asked the Chancellor to put together such a timetable and I believe this shall be enough to encourage those who have cut wages to consider raising them somewhat in line with the new rates. Where wages have been raised by just a few pence, we are seeing a return to work and the termination of strike action. I am sure it shall prove to be the case when such an approach becomes standard as the result of this new measure”

This announcement was not entirely warmly received. Whilst it would no doubt encourage some to return to the factories or mills, it did not address those issues which had become the new driving force of the movement as adopted by the Chartists. Gladstone was the only one willing to say so openly.

“I concede we may see a return to work under this plan Prime Minister”, he said softly, “But surely this will do very little to silence the Chartists-“

The room was suddenly filled with a loud bang as Sir James struck the table.

“Damn it, I do not wish to hear one more word about the bloody Chartists!”, he raged, “Do you not see, Gladstone, that the Chartists do not feed the people they lead onto the streets? Are you so foolish as to believe that the people marching and striking and smashing shop front windows are doing so because they believe in Chartist principles? For goodness’ sake man, half of the beggars can’t read their own names, let alone the pamphlets these layabouts publish! We shall pursue this and we shall see an end to these strikes and if we do not, then we shall take further measures against the Chartists directly and we shall keep doing so until every last one of them is transported, if that's what it takes, do I make myself clear?"

He had perhaps made himself a little too clear.

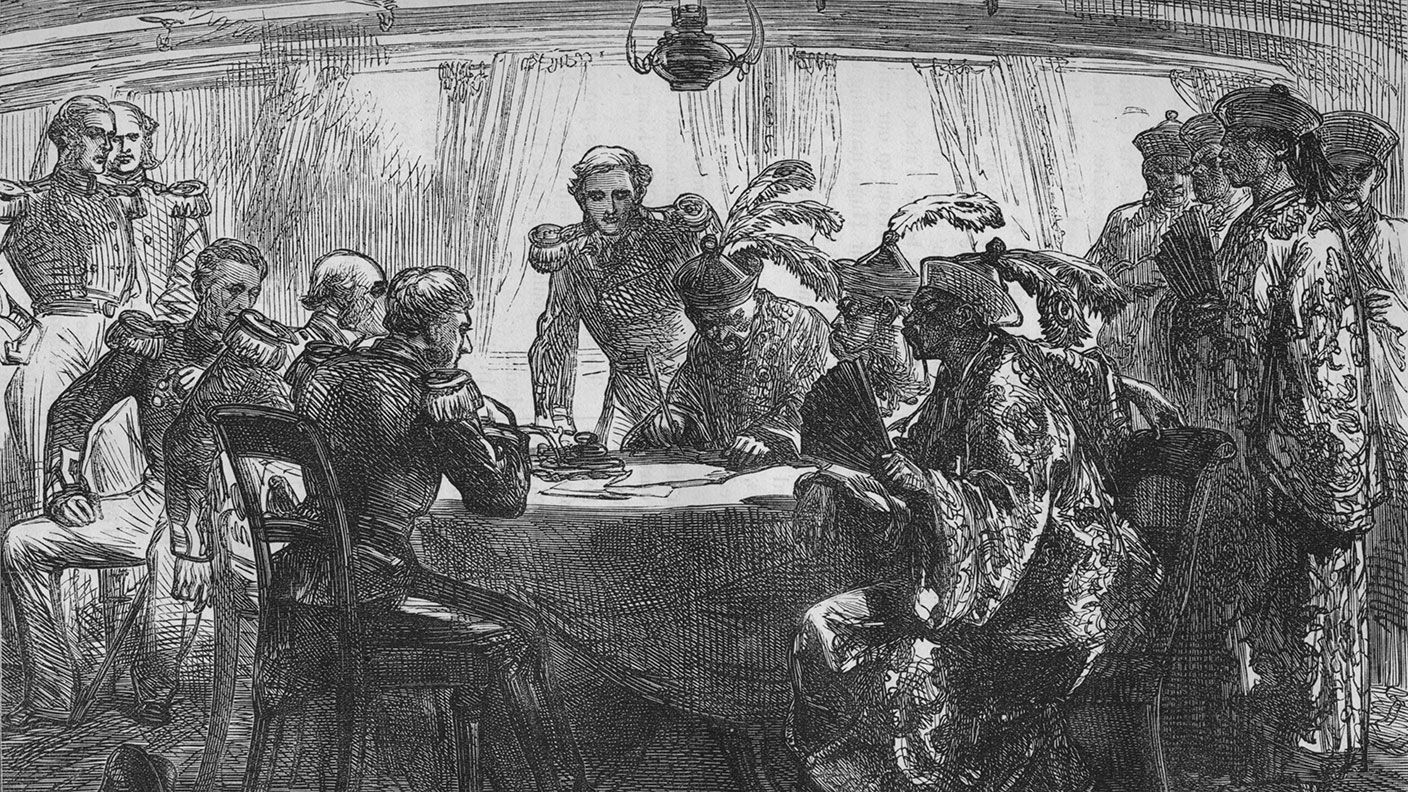

The Qing come to terms at Nanking, from a British newspaper, 1842.

The meeting then moved on to peace talks at Nanking. Shattered, broken and humiliated by the swift British victory, the Qing would forever regard the Treaty of Nanking as an unequal one in which they were unfairly exploited. The Treaty broke the Canton System which had been in place since 1760 and had allowed China to keep the Western powers at arm’s length. Now, four “treaty ports” were to be established with open-access to all foreign traders with British consuls given the right to station themselves at Amoy, Foochow, Ningpo and Shanghai in addition to their existing concerns at Canton. This would see British trade routes in the Far East re-open almost immediately and with far more profitable results than ever before. This was good news for a beleaguered British economy but the Treasury had still had to fund an expensive campaign it could ill-afford. This was easily remedied with a clause in the Nanking Treaty which forced the Qing government to pay the British government the total sum of £25m within three years with an annual interest rate of 4% for any monies not paid in a timely fashion. The £25m was to serve as compensation; £3m was said to be owed for the loss of confiscated opium whilst £22m would serve to repay the cost of the war itself. But by far the biggest advantage to the United Kingdom was the cessation of Hong Kong. It was a staggering blow to the Qing as they had no choice but to agree to hand over Hong Kong which was declared a crown colony under British rule in perpetuity.

“So let us be united gentlemen”, the Prime Minister said enthusiastically, “For this is the proof of what we can achieve when we are so”. Sir James caught Gladstone’s eye. It must be remembered that Gladstone had opposed the China War, even threatening to resign if Britain took up arms against the Qing. In the event, Gladstone remained in his post because he reasoned that the United Kingdom had been left with no choice but to fight the Chinese. Yet with one look, the Prime Minister had effectively warned Gladstone that he had been lucky to keep his job before, and furthermore, his objections that the war would not be easily won, or that the outcome could not be guaranteed, had been proven to be unfounded. Whilst Graham did not wish to sack Gladstone as some of his Cabinet might have wished, cracks were beginning to develop in the delicately forged united front the Tories had been able to present for so long – and the Whigs were poised, waiting to take advantage of it.

Some days later, the Duke of Buccleuch requested an audience with the King at Buckingham Palace. George V had been keen to keep the Buccleuchs at arm’s length since the death of his wife earlier that year but as the Duke was Lord President of the Council, this could only last for so long before the Prime Minister might consider he had reasonable cause to demand that such a meeting take place. However, Sir James Graham was spared this when a Privy Council matter that required the King’s urgent attention reared its head. A letter had made its way to Buccleuch from Prince George of Cambridge. He was formally requesting permission from the Privy Council to marry Franziska Fritz; “In much the same way as consent was given by His Majesty’s Privy Councillors to the marriage of my uncle, the Duke of Sussex, I now petition the same privilege be conferred upon me as I seek to marry before the conclusion of the year”. It appeared Prince George had made his decision. Buccleuch knew only too well what the answer would be, yet he was duty bound to present the petition to the King. Entering the King’s study, Buccleuch chose to tear off the band aid and quickly address the situation at hand.

“I have had a request from His Royal Highness Prince George of Cambridge”, the Duke said hurriedly, “It is to ask the Privy Council to give him permission…”

“No”, the King said flatly, refusing to look up from his state papers.

“Yes Sir, as it stands His Royal Highness is not yet 25 and-“ [7]

“Not Royal Highness”, the King muttered, again seemingly unwilling to look the Duke of Buccleuch in the eye, “Not anymore he’s not”

“Quite...”

A frosty silence reigned. Finally, the King looked up.

“Well?”, he said unkindly, “What else is there?”

Buccleuch thought for a moment. And then decided now was not quite the time.

“Nothing Sir…I bid you good night”

And with that Buccleuch left the room. The King sighed deeply and shook his head. Was it really so bad that his cousin had found somebody he loved and wished to make his bride? After all, wasn’t that just what the Duke of Sussex had done and which the King had so recently sanctioned? And if the King could, would he not give his Crown and every jewel in it for just a few precious moments more with the woman he loved? George reached across his desk and grabbed a piece of notepaper.

“Cousin, George…”, he began.

Then he thought better of it, scrubbed out the words with his pen, balled up the notepaper and threw it toward the fire.

By the end of September 1842, ‘Cousin George’ had his formal reply from the Privy Council. No such consideration to approve his marriage could be given as he had not yet turned 25. “Furthermore Sir”, Buccleuch wrote to the Prince, “It is my regret to inform you that His Majesty has prepared an Order-in-Council concerning this matter, the particulars of which I shall not include here but which I believe are well known to you already”. Little did George know it, but this would mark the last time he would ever receive a letter from England addressed to His Royal Highness Prince George of Cambridge, though it was this name which he entered into the Parish Register of the Allerheiligenkirche in Erfurt on the 31st of October 1842 when he married Franziska Fritz. As the marriage was unrecognised in England, Fritz was not entitled to the courtesy title of Countess of Tipperary. From the moment he said "I do“, His Royal Highness Prince George of Cambridge lost everything; his royal rank, his career, but most importantly, his family.

For the remainder of the decade, there would be no communication between George and his family. His parents absolutely forbad his sisters to write to him, the King issuing similar instructions in England. He did not visit the United Kingdom, nor Hanover, and chose to settle in a small house in Kirchheim on the banks of the River Wipfra. The “small sum” given to him by his father before his departure from Herrenhausen was a little over £500, the equivalent of £30,000 today, which was just enough to lease the farmhouse at Kirchheim and to take in a small staff of just three; a footman-valet, a cook and a housemaid. This was to become George’s home for the next two years but his penchant for lavish spending (matched thaler for thaler by his new bride) quickly saw their meagre nest egg disappear. George’s marriage shocked and appalled the royal courts of Europe and forever after, he would be known as ‘Poor George’ – though this might apply just as much to his reduced station and banishment from his family home as to his financial circumstances. The former Prince quickly became a disturbing example to other young men in his position as to what might happen if they did not behave themselves.

But for King George V, his cousin became a regular presence pricking at his conscience. And this only increased as the years went by. All George Cambridge could hope is that one day soon, the King would become so tired of such nagging thoughts, that he may relent and bring Prince George back into the family fold…

Notes

[1] His courtesy title was Lord John Russell but as he did not yet hold a peerage in his own right, Russell was still able to stand for election to the Commons.

[2] This figure was the same in the OTL.

[3] Again, as in the OTL.

[4] You can read more about Lord Liverpool and his "Six Acts" as they appeared in TTL here: https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...-british-monarchy.514810/page-2#post-22266414

[5] I failed to mention Peel's departure earlier but it actually fits quite neatly here.

[6] As in the OTL, men like Gladstone and Graham were already questioning their continued support of the Corn Laws a few years before the famine in Ireland forced their hand and they agreed to support a repeal.

[7] At 25, the Privy Council could consider the matter without the King's consent pending parliament's approval.

With other OTL events now concluded, I'm back to my previous schedule so there'll definitely be more than just one chapter this week - unless the cold I picked up over the weekend gets any worse! When I am asked in years to come where I was when Queen Elizabeth II's State Funeral took place, I will have to answer; "Tucked up on the sofa with Kleenex and Night Nurse".

This instalment marks the departure of Prince George for a little while as he's now served his purpose - for the time being. But he'll prove important in the future and I hope that when we reach that stage, you'll see why George married Franziska and not Sarah Fairbrother as he did in the OTL. That said, with so many characters it's a bit of a plate spinning act and as one is retired for a little while, other favourites can make a return for a while. So keep your eyes peeled...

Did anything like this happen OTL? Because I would consider it highly unlikely that anyone would make such a simple connection.But the income tax nipped at their purse strings and the obvious way to offset this new expense was simply to slash wages. This approach was nicknamed the ‘Baring Cut’ ...

First, the income tax would apply to all high-income persons, not just factory owners. While industry had begun to displace land as the primary form of wealth, in the 1840s there were still as many landholders as industrialists, and also bankers, merchants, shipowners, canal and railroad operators, mine-owners, builders...

Second, the tax was graduated, with a large exemption. So small factory owners would be much less affected.

Third, the profitability of factory operations varied widely, from year to year, and between different industries, different parts of the country, and different managements. Would the owners of a very profitable works insist on making up for a modest (by modern standards) tax bite on their personal incomes by cutting wages, and incur the risk of strikes and other disruption that could spoil their generous profits? Would the owners of a works barely scraping by, so that they have very little income to pay tax on, cut wages and provoke labor troubles that could put them entirely out of business?

Fourth, many factories were owned by corporations, with a diversity of shareholders. Some of these were landowning gentry, whose dividends were only a part of their income, and who might be invested in several different concerns. Some were small investors, whose income did not reach the taxable threshold.

Are all these people going to show up at shareholders' meetings, demanding that the corporation cut wages to increase dividends?

So ISTM implausible that a tax on incomes would lead to across the board wage cuts.

Last edited:

Wow, another great chapter. Looks like it’s Gladstone Vs the world at this point. Hopefully, Great Britain is able to get out of this economic situation. Was the real George Cambridge the spendthrift-partier this George Cambridge is?

This is based on an OTL scenario from the actual time period. I have absolutely no idea about economics so I've had to model it as I found it in my research but the basic situation as I understand it was that the income tax was so hated that industrialists in particular slashed wages to offset the new rates they had to pay. I'm sure other wealthy people took similar action (cutting the wages of domestics or raising tenants rent etc) but I only focused on factories and mills as it allowed me to reintroduce the Chartists around this time.Did anything like this happen OTL? Because I would consider it highly unlikely that anyone would make such a simple connection.

Thank you so much!Wow, another great chapter. Looks like it’s Gladstone Vs the world at this point. Hopefully, Great Britain is able to get out of this economic situation. Was the real George Cambridge the spendthrift-partier this George Cambridge is?

The whole Cambridge clan were pretty hopeless with money! When the Duke of Cambridge died in 1850, Cambridge House had to be sold off to pay his enormous debts and it seems this was a family trait.

The OTL Prince George was very lavish in his spending habits and most of what we know in this direction comes from the James Pope-Hennessy biography of Queen Mary. Her parents (George's sister Mary Adelaide - later Duchess of Teck) was so poorly off due to her excessive spending that a family trust had to be set up to stop the Duchess of Teck from getting into any more debt. There was a even a time when the Tecks had to leave England to live in Italy to escape their debtors.

Prince George was made a trustee of a special fund set up by his mother which Mary Adelaide could draw on and if she needed any more cash, she had to write to George and tell him what the additional money would be used for. The Duchess of Teck was outraged by this because Prince George was renowned for betting more than he could afford and consistently found himself in debt trying to pay it all off. She appealed to Queen Victoria and was told there was no money more, would never be any more money and that though Prince George was just as irresponsible at times, he at least honoured his debts whilst Mary Adelaide tended to ignore them and pretend they didn't exist.

VVD0D95

Banned

Lol she sounds a real poece of work and the complete opposite of her daughterThis is based on an OTL scenario from the actual time period. I have absolutely no idea about economics so I've had to model it as I found it in my research but the basic situation as I understand it was that the income tax was so hated that industrialists in particular slashed wages to offset the new rates they had to pay. I'm sure other wealthy people took similar action (cutting the wages of domestics or raising tenants rent etc) but I only focused on factories and mills as it allowed me to reintroduce the Chartists around this time.

Thank you so much!

The whole Cambridge clan were pretty hopeless with money! When the Duke of Cambridge died in 1850, Cambridge House had to be sold off to pay his enormous debts and it seems this was a family trait.

The OTL Prince George was very lavish in his spending habits and most of what we know in this direction comes from the James Pope-Hennessy biography of Queen Mary. Her parents (George's sister Mary Adelaide - later Duchess of Teck) was so poorly off due to her excessive spending that a family trust had to be set up to stop the Duchess of Teck from getting into any more debt. There was a even a time when the Tecks had to leave England to live in Italy to escape their debtors.

Prince George was made a trustee of a special fund set up by his mother which Mary Adelaide could draw on and if she needed any more cash, she had to write to George and tell him what the additional money would be used for. The Duchess of Teck was outraged by this because Prince George was renowned for betting more than he could afford and consistently found himself in debt trying to pay it all off. She appealed to Queen Victoria and was told there was no money more, would never be any more money and that though Prince George was just as irresponsible at times, he at least honoured his debts whilst Mary Adelaide tended to ignore them and pretend they didn't exist.

She was quite something! Her family mocked her her entire life because she was so enormous and because she didn't marry particularly well and yet she did so much good and was so well liked by the people that when she died, she earned herself the moniker "The People's Princess". Famously recycled in 1997 of course...Lol she sounds a real poece of work and the complete opposite of her daughter

I hope Gladstone is able to weather out the storm of men who are trying to force him out. Just a quick question. How did Gladstone get into power earlier than he did IOTL?

He was very much a Graham ally in the OTL around this time when it looked as if Sir James might stand a chance at the premiership so it seemed to make sense to bring him into the Cabinet when Graham took office.I hope Gladstone is able to weather out the storm of men who are trying to force him out. Just a quick question. How did Gladstone get into power earlier than he did IOTL?

GV: Part Three, Chapter Eight: The King Returns

King George V

Part Three, Chapter Eight: The King Returns

Part Three, Chapter Eight: The King Returns

Although court mourning for the late Queen Louise formally ended in July 1842, there remained one tangible reminder of the King’s loss – his continued absence from public life. This may give the impression that King George V was so burdened down by grief that he became a kind of hermit tucked away in luxurious solitude but this wasn’t at all the case. Indeed, when court mourning ended the King put away his sombre wardrobe of black and introduced colour again. Friends and officials alike were invited to the Palace once more for small dinner parties, music returned and the last vestiges of black crepe draped over portraits and the like were finally removed. The Court Chaplains were told that they were no longer bound to ask for a moment of silence for the “repose of the soul of our late Queen” during their daily prayers for the Royal Family and even the florists who provided blooms to the vases throughout the royal residences were advised that white lilies might now be retired and that other blooms may be slowly reintroduced. The King had never shirked his duties, not even in the depths of his grief in the early days of his bereavement, but now he balanced his state papers with private audiences and visits to friends both in London and at Windsor, aided greatly by the arrival of his own private railway carriage in October 1842 which caused some confusion with the Royal Household who couldn’t work out whether it should be kept at the Royal Mews or at London’s Paddington Station. Common sense prevailed and a garage was constructed to store the Royal Train Carriage at the terminus. [1]

In terms of public life however, the King had yet to be seen and this began to trouble those in his service not because they feared the public might lose any affection for George V but more because the King seemed to be frightened of appearing in public. His Private Secretary, Charlie Phipps, believed it was “in no way motivated by ingratitude, His Majesty was greatly consoled and comforted by the expression of grief from his people after Queen Louise’s death. But I maintained then as I do now, that a return to the entirety of his duties as Sovereign would herald a return to a life for His Majesty that would seem both familiar and yet painfully different and I believe he found the prospect really quite overwhelming”. Phipps became increasingly aware than when he sent the King a schedule, the more public elements of it were crossed out in red pencil – the agreed sign that something did not meet with His Majesty’s approval and should be replaced by something else. The Foreign Office, for example, wished to invite the King of Prussia for a state visit, which the King agreed to. But the river pageant and public welcome ceremony at Hampton Court was “red-lined” and instead, Phipps had to inform the Foreign Secretary that despite the King’s intention to use Hampton Court for the purpose, the state visit would instead take place at Buckingham Palace and with no procession from St Katharine’s Dock, at least not with the King riding out to receive his guests.

Of course, this was possibly a very wise move on the part of the King at this time (though undoubtedly this was not his motivation) for in October 1842, the ongoing strike action and anti-government feeling among the working classes was reaching it’s peak. The talk of a general strike had been mounting for weeks and nobody quite knew how severe the consequences would be. Yet something began to change within the body of the strikes that saw a slow but steady crossing of the picket lines. The Chartists had been revived and renewed by the demonstrations and they had successfully taken control of the strikes so as to organise them more effectively than civil unrest had been co-ordinated for years, if ever. But they began to push their own agenda over the reason so many had walked out and downed tools in the first place. Those attending Chartist demonstrations began to hear less about wage cuts and unfair working conditions and more about the disestablishment of the Church of England or the abolition of the monarchy and these were not principles they shared – or even cared about [2]. The government’s presentation of a timetable to phase out the income tax also had results and around 60% of those who had imposed the Baring Cut agreed to raise worker’s wages again – it wasn’t the pre-cut wage but it was a step in the right direction. It seemed that the Chartists had tried to hijack a cause for their own ends and the vast majority of employers who did raise pay did so without committing to the so-called People’s Charter. The majority of strikers too seemed not to care whether their employers signed or not. Principles were a luxury most could not afford. The threat of the general strike trickled away and though strike action was still reported in the North of England and the Midlands, by the end of October 1842, the worst danger had passed and Britons seemed to be going back to work. Some in government celebrated. But Sir James Graham knew better.

Sir James Graham

In the second week of that month, a by-election was held in Brighton. The incumbent Whig MP, Isaac Newton Wigney had been declared bankrupt and was obliged to resign his seat in the Commons [3]. Despite the economic problems and widespread strikes of the last few weeks, the Tories expected to take the seat comfortably. In the event, the Unionists split the Tory vote and though their candidate, Lord Alfred Hervey, was elected by 277 votes, when the returning officer’s report came to Downing Street the Prime Minister saw something that worried him. Even when the Whig vote was split by the Radical and the Chartist candidates, the Whigs not been far off holding the constituency. Graham became concerned that the new double-act of Melbury and Russell was restoring the Whig party fortunes and that divisions creeping into the Tory party might be more damaging than he first thought they might be. Though there had admittedly been problems for the government, and whilst the incumbent ruling party might expect to lose seats in office rather than gain them, the Prime Minister knew that something had to change. For too long he had been focused on repairing the damage left by the previous administration. But now he had proved himself. He had averted a general strike and restored Britain’s standing abroad with a victory against the Qing, securing a new crown colony in the process [4]. It was time for Graham to begin making his own mark with a raft of reforms that would beat back the opposition to their 1840 standing with the public and ensure him a second term in office when the time came.

To begin this reinvention, Graham decided on a two-pronged strategy. Firstly, he would instigate the so-called “Good News Policy”, whereby Tory friendly newspaper barons were encouraged to print only positive stories about the government on the pretext that anything else may inflame tensions once more. The newspapers needn’t worry about what good news they should print, the government was only too happy to provide that. There were new commitments given to build more schools, to address labour conditions, to reform housing standards and to invest in major infrastructure projects as the nation’s finances allowed. Journalists were discouraged from dwelling on the unpleasantness of the past; the disaster of Bala Hissar, the violence of the recent strikes, even the death of the late Queen. This was nothing more than propaganda of course but the press of 1842 remembered only too well what life had been like when their freedom to print what they liked was swiftly removed at a time of national strife. Graham warned, though subtly, that those who “took an unhealthy interest in civil disobedience may bear some of the responsibility for the fruit it bears” and as a result, most in the Tory press were only too happy to go along in reporting “Graham’s good news”. But good news for some was bad news for others. The second aspect of this new approach to governance from the Prime Minister was to avoid division in his Cabinet, not by bringing them closer together but by removing those who had caused unpleasantness. The average term of government was four years, Sir Graham was in the mid-term phase and it was quite natural that he should want to make a few adjustments. But this went beyond the odd promotion or sacking; Graham intended to sweep the Cabinet clean.

At Buckingham Palace, the King looked over the list of new Cabinet appointments and drew his own conclusions. The Duke of Buccleuch was out. He had overplayed his hand and been too demanding in pushing for William Gladstone's removal. Graham had to remind his party who was in charge and it wasn’t Buccleuch. Gladstone himself remained in post at the Home Office but with a warning; never again would he give Graham an ultimatum. He was to follow the party line or he was to return to the backbenches, whether he mounted a rival grouping or not. Gladstone agreed. But the biggest scalp of all was Baring’s as Chancellor of the Exchequer. Officially, Baring was not being sacked, rather he was being asked to undertake a special diplomatic mission to secure a treaty resolving border issues between the United States and the British North American Colonies (Canada) which the Prime Minister publicly stated in the Commons “was a task only Lord Ashburton could perform” [5]. Nobody believed it for a second. Baring was a money man. This diplomatic posting was simply an honourable discharge and Baring grabbed it to avoid the inevitable blame if the economy did collapse. Lord Stanley lost the Foreign Office and was moved to the Ministry for War but in his case, this was seen as a promotion because he had worked so hard to secure victory in China at a time when his counterpart in the War Office, Thomas Fremantle (Lord Cottesloe), had gone “a little off the boil” – in actual fact, Cottesloe had admitted to disliking the post and had asked to be put somewhere else. He was “rewarded” by being made Chief Secretary to Ireland.

All of these appointments were rubber stamped by George V and he sent a handful of complimentary notes to those were once again returned to the backbenches offering his thanks for their service. The only issue he took with the new Cabinet was the departure of Lord Stanley from the War Office. In a letter to Stanley, the King wrote, “The situation in China might never have been resolved as efficiently and as advantageously as it was without your efforts”, the closest the King could go without saying what he really thought and what his diary reveals; “Stanley is the best of this government and he shall be wasted at the War Office until the next campaign rears its ugly head. I call that very feeble”. Stanley had actually asked to stay at the Foreign Office but Graham wouldn’t hear of it. He had dominated Cabinet whilst Britain had been at War. Now he needed a little time in the shade and with no urgent military adventures on the horizon, the Prime Minister felt it best to “let Stanley cool his guns for a time”. Fortunately for the King however, there were no changes to the Royal Household and the benefit of this was particularly noticed in the coming weeks as the Prime Minister tried to apply his “Good News” policy to the Crown.

In an effort to redirect attention away from recent difficulties (and a reshuffle), the Prime Minister approached the Bishop of London and asked him if he could see his way to arranging a Service of Thanksgiving for the Victory in the Far East now that China had come to terms and the Treaty of Nanking had been ratified by both sides. This was to be expected, though Sir James wanted to embellish the event with a victory parade. Whilst traditional, the public hadn’t taken as much interest in the China War as they might have done otherwise because it had been so tinged with the debate on the opium trade. What with the recent social unrest too, even the Chiefs of the General Staff were not inclined to stage anything particularly lavish either. It was therefore agreed that a simple procession of regimental colours would take place followed by the usual big wigs of the City of London, the more senior members of government and of course the Prime Minister. But Sir James would not cut back when it came to representation of the Royal Family. Bearing in mind that Sir James had once caused much unpleasantness in order to remind the King that he should remain impartial, now it seemed that (somewhat hypocritically), the Prime Minister wanted to be seen in public with the King, possibly because he felt it would do him some good politically, to remind those looking on that George V still had every confidence in Graham personally. This did not go down well at Buckingham Palace for this very reason and the King “red-lined” his appearance at the service at St Paul’s asking Phipps to dispatch Princess Mary to represent the Crown instead.

In 1842, the modern concept of a “working member of the Royal Family” did not exist. Though they frequently visited hospitals, unveiled statues, toured galleries and the like, it was by no means expected that the King and his family would conduct a full programme of appearances or even be seen to make more than a handful of public entrances each year. Even then, the majority of their engagements were staged in the capital and public appearances elsewhere were few and far between. Unlike today when this would raise serious questions about the monarchy’s value for money, this was widely accepted the status quo and though some may wonder some 200 years later how he never even considered it, it was by no means unusual that in his 15-year reign (man and boy), King George V had visited Germany more often than he had visited Scotland or Wales. But there were set piece events each year which drew enormous crowds as the people seized a rare opportunity to glimpse the Sovereign. People quite understood why the King did not attend the State Opening of Parliament in 1842 but by October, the last time the public had seen the King “in person” was at his wife’s funeral and there were already thinly veiled criticisms of this in some of the more liberal newspapers. The majority of the King’s advisors didn’t take this seriously even when he declined to go to St Paul’s because they believed he would relent and make a public appearance when the King of Prussia came to England for his State Visit. But Charlie Phipps knew better and he was beginning to get worried.

Benjamin Disraeli

Phipps had become increasingly friendly with the Comptroller of the Household, Benjamin Disraeli, especially after he had proved so useful in preventing the King from being dragged into a political scandal when he spent a little too much time at the rival Whig court in Bloomsbury Square. Disraeli had kept his post in the reshuffle and now, it was Disraeli whom Phipps decided to consult on this difficult problem of convincing the King to return to his people before the situation deteriorated any further. Disraeli listened intently to Phipps’ concerns. He agreed that the King should have attended the service at St Paul’s but that in a wider context, the absence of the King from the public stage was not good for the monarchy – or the country as a whole. In 1842, the Royal Family had very few “working” members, that is to say that only the King, Princess Mary, the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge and (very occasionally) the Duke of Sussex were able to carry out public engagements. But the Cambridges were in Hanover and the Duke of Sussex was unwell. With this in mind, the King could not afford to retreat from public life much longer as the monarchy faced the very real prospect of fading from view.

As Comptroller of the Household, Disraeli served as a kind of bridge between Palace and Cabinet. Once again, it would be Disraeli who would use his unique position with important contacts on both sides of the constitutional divide to assist the King in a time of difficulty. After his conversation with Phipps, Disraeli visited the new Leader of the House of Commons, George Smythe. Smythe had served as Under Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and was well known to the King as he had accompanied him to Normandy two years previously. But he was also a close friend to Benjamin Disraeli, Smythe’s father having sponsored Disraeli for membership of the Carlton Club. Disraeli explained to Phipps that there was a possibility of rising tensions between Downing Street and the Palace once again as the King seemed reluctant to make a public appearance and in his usual erudite way, he spoke at length of the importance of the monarchy “being seen to be believed”. Smythe quite agreed and together, they hatched a plan that they hoped would coax the King out of hiding. At the next Cabinet meeting, Smythe listed the government business of the day but he had taken it upon himself to add one important debate to the agenda; a motion to provide funds for a public memorial to be built in honour of the late Queen.

This debate, A Motion for the Provision of Funds to Erect a Public Memorial to Commemorate the life of Her Late Majesty Queen Louise of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, etc, was the first step in securing the £20,000 required to construct a suitable memorial to the late Queen in London. Usually, an individual might not be honoured in such a way until years after their death, but Smythe presented his proposal to bring things forward so that the memorial might be unveiled in the Spring of 1843 to coincide with the first anniversary of the Queen’s death which he suggested was “a more elegant progress” than relying on a parliamentary committee. Graham approved and besides, that could go on for months which might draw unattractive criticisms of the cost. Smythe was given the go ahead and so in October 1842, the House of Commons voted to grant £20,000 to a fund for the purpose of building a suitable memorial to the late Queen. Smythe had done his part, now it was up to Disraeli.

Disraeli had a particular flair for interacting with royalty. He knew how to flatter without sycophancy but he also knew how to steer without overstepping the boundaries that existed between King and subject. Disraeli reported to His Majesty that parliament had voted the sum of £20,000 for a memorial and that the Cabinet was united in their view that Decimus Burton should be commission to design it. At first, the King was a little stunned by the news. It must have been a painful thing to consider, yet he was touched that such a memorial was to be provided and it must be said he was relieved that it would be Burton who would design the tribute. But the King was insistent on two points concerning the memorial; the first was that it should in no way depict the Queen in effigy. The second was that the memorial must be placed in a prominent position where it would be easily viewed by all Londoners but that it must be kept away from the hustle and bustle of the street traffic. Disraeli took these conditions to Burton and after a week or so, Burton was ready to present his first designs for approval and to formally request permission from the Crown Estate to access the site he believed suited the King’s requirements.

Burton's original design for Memorial Arch.

Today, those visiting London can see for themselves the fruits of Burton’s labours. Walking along the Constitution Hill road banked with oak trees on each side which cuts through Green Park, tourists then come to the Royal Circle, a modest area of parkland opposite Apsley House, its border marked by a perfectly round colonnade with two enormous gates at each entrance. Initially known as the North and South Gate, these were renamed the George V and Queen Louise Gate respectively in 1890. In the centre of the Royal Circle, neatly banked by flower beds and carefully plotted gravel paths, is Memorial Arch, the centrepiece of Hyde Park Corner and which was built so tall so as to be seen whether one approaches from Park Lane in the North, Grosvenor Place in the South or Knightsbridge in the West [6]. The Arch was Burton’s answer to providing a memorial that had no effigy and it stands at 28 metres, fashioned from Portland Stone with a single entrance banked by Corinthian columns and lightly decorated with laurel wreaths inside which are held the initials LR for Louise Regina surmounted by a crown. At each corner, supporting the gallery above, are four heraldic beasts; the Lion and the Unicorn for the United Kingdom and the Griffin and the Bull for Mecklenburg-Strelitz, a nod to the Queen’s homeland. But perhaps the most important feature from the point of view of Disraeli and Smythe is not the arch itself but the foundation stone which can be found tucked neatly into the centre path. It reads:-

This foundation stone was laid by His Majesty King George V on the 30th of October 1842.

As inscriptions go, it's hardly Shelley or Keats and is unlikely to provoke anything more than the casual interest of the tourist today but it represented something extremely important to those involved in it's creation in 1842. Though Memorial Arch and it’s environs went way over budget and took 18 months to unveil rather than the six months Burton originally predicted, Disraeli proposed the laying of a foundation stone in a small public ceremony to take place as soon as possible, an engagement he knew the King would not deputise [7]. Sure enough, on the 30th October 1842, the King made the brief journey from Buckingham Palace to Hyde Park Corner and for the first time in months, the public were able not only to catch a glimpse of him but to interact with him too. As nervous as he may have been, there was no trace of it as the King gave his blessing to the stone as it was lowered into the ground and then, as was his style, he broke away from the stony faced officials in their extravagant costumes and made his way to the edge of the crowds, conversing with a fortunate few. One such encounter was reported in a newspaper and is perhaps the most moving account of what transpired that day.

Seeing a Mr Baker in the crowd, His Majesty paused for a moment and said, ‘Your face is familiar to me’. Mr Baker, now in his 68th year, told the King that indeed he was correct for Mr Baker had worked at Windsor for a time. Whilst this recollection was being shared however, a very loud voice came from behind Mr Baker from an elderly man who said, “Where have you been then Georgie?”. His Majesty was not at all offended by this outrageous display of familiarity, indeed, he was said to be quite delighted by it and smiled. “We did miss you”, the man continued. And the King replied, “And I missed you all very much too. I thank you for your kindness to me and to my children. I shall not leave you for so long again”.

This marked the end of what was possibly the most difficult period of George V’s life. Though naturally he would always miss Queen Louise’s presence and though he still grieved that her children would have no memory of her, it seems that this occasion wrestled the King from the last vestiges of his pain and sorrow and pushed him towards the future. By going among his people again, the King was perhaps reminded of what it was all for and within days, his friends, family and staff noted a distinct change in him. Suddenly, he began to talk only of the future and not the past and by the beginning of November, nobody was left in any doubt that he had truly turned a corner. There can be no greater example of this perhaps than when he summoned his cousin Princess Augusta of Cambridge to Buckingham Palace. Regardless of her brother’s activities of recent months, the King held firm to his promise never to raise the matter and never to treat the other members of the Cambridge family any differently from before.

The King received Augusta not in his Study as he usually did but in the Blue Closet, a favourite room of the late Queen’s at Buckingham Palace which had been left empty since February.

“And have you heard much from Fritz?”, George asked teasing his cousin a little, “Or will you stay an old maid forever and knit ugly things for us all to wear?”

“Oh Georgie!”, Augusta giggled, “I hope to see him again at Christmas”

The King shook his head, not so much sadly but more as if he had resigned himself to things.

“I shan’t bother with Christmas this year”, he said wistfully, “At least not in the way we used to. Seems a little pointless, what? It’s only Aunt Mary and I, now that poor old Uncle Sussex has been laid low”

“How is he?”, Augusta asked kindly.

“Bearing up they say", the King replied, "But he's getting old you know? I'm going to see him tomorrow morning, I shall give him your best"

“Well I shall be here, if you want me to be. For Christmas, I mean”

The King smiled warmly.

“No you won’t”, he said, adopting a haughty air, “Because your King has a command for you, cousin dearest”

The King jumped playfully to his feet and held out his hands. Augusta stood up nervously and took them.

“You are to go to Neustrelitz. I’ve already written to Mama and told her to expect you. And when you get there, you will tell my dear brother-in-law that we all need cheering up. So I think it's high time that he did the decent thing and proposed to you. And you can tell him from me that if he doesn't, I shall have him locked in the tower until he does!”

Augusta began to cry through her broad smile.

“Oh Georgie…we wanted to before but…well…”

“I know”, the King said, kissing Augusta’s tear-stained cheek, “But we can’t take back the past. We can only look to the future. And I know yours shall be a very happy one with Fritz. So you had better tell him yes. Mind you, if you think I shall let my favourite cousin marry in that horrid little church in Neustrelitz then you’re very much mistaken. It’s about time this Palace had a celebration in it again!”

Princess Augusta returned the King’s kiss and curtsied.

“Thank you Georgie”, she said gratefully, “Bless your heart for saying that”

“Oh don’t bless me yet”, the King replied teasing her, “Bless me in 50 years when you’ve had a long and happy marriage. Which I know you shall”

Augusta thanked the King again and made to leave. She was taking supper with Princess Mary and daren’t be late.

“Oh Augusta…”, the King called out behind her as she approached the door, “Just one more thing…”

“Yes Georgie?”

“You might do something for me if you’re passing the nursery floor?”

“Of course”

“Tell Lady Maria to bring the Princess Royal to me this evening. On her own mind. I want to spend some time with her before…before you take her back with you...”

Princess Augusta paused for a moment. Then she curtsied deeply again. In that moment, she could not possibly admire her cousin more.

Notes

[1] At this time in the OTL, Queen Victoria was pondering such a commission but it would be years before the Royal Family would commission their own engine to pull the carriage and establish the Royal Train we know today.

[2] This was actually a criticism of the Chartists in the OTL around this time which I've included here as it's important to recognise that not everybody marching with the Chartist banner actually knew or agreed with their entire platform.

[3] Taken from the OTL but delayed a little and added to to fit our narrative here.

[4] Hong Kong.

[5] This posting for Baring came at this point in the OTL and Cottesloe did in fact go to Ireland as Chief Secretary around this time too.

[6] This is actually Wellington Arch which Burton designed in 1825, along with the redevelopment of what became Apsley Way, but which didn't occur in this TL because that project was commissioned and funded by the OTL George IV. Here we keep a prominent London landmark but it has a different origin story and a slightly different surrounding. I've had to cut the quadriga off the top because whilst this wasn't added until 1846, it was very tricky to find an image of the original arch without it.

[7] It was actually Disraeli who came up with a similar plan in the OTL when Prince Albert died. He realised the only way to get Victoria back in the public eye was to build memorials to Albert and have her unveil them - a task she wouldn't deputise to others. Sadly this proved to be true just twice and thereafter, she did hand the job over to her family and stayed at home. Here, the King departs from the OTL approach of Queen Victoria and the monarchy, despite it's personal tragedy, isn't defined by mourning and loss for the next 60 years.

And so just as we begin to move into a new year, this really does mark the turning point for the King as a chapter is closed on Queen Louise and he prepares for a future without her - not forever scarred by it like the OTL Queen Victoria, but resigned to it. Augusta will be married in 1843 as she was in the OTL but we'll also see Missy return to Neustrelitz and then her school in Leipzig. And in the next instalment, we'll see an old favourite return which I know many of you have asked me for in my DMs so thank you for your patience in waiting to see her again!

Before I forget, for those keeping up to date with the Cabinet lists, this is the Second Graham Ministry appointed in 1842.

- First Lord of the Treasury and Leader of the House of Lords: Sir James Graham, 1st Earl of Naworth

- Chancellor of the Exchequer: J.C Herries

- Leader of the House of Commons: George Smythe, 7th Viscount Strangford

- Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs: Henry Goulburn, 1st Earl of Betchworth

- Secretary of State for the Home Department: William Ewart Gladstone

- Secretary of State for War and the Colonies: Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby

- Lord Chancellor: Edward Sugden, 1st Baron St Leonards

- Lord President of the Council: Lord Granville Somerset

- Lord Privy Seal: James Stuart-Wortley, 1st Baron Wharncliffe

- First Lord of the Admiralty: Robert Dundas, 2nd Viscount Melville

- President of the Board of Control: Sir Edward Stanley

- Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster: William á Court, 1st Baron Heytesbury

- Postmaster-General: Francis Nathaniel Conyngham, 2nd Marquess Conyngham

P.S - Please forgive the fact that on this occasion I haven't added in who each incoming Minister replaced as I usually would. My cold did indeed turn into something much nastier and I've been confined to bed for a week with the flu! I'm still a bit dopey and wracked with a nasty cough and so I thought I'd get a new chapter out for you as the priority rather than delay it further for what can be a minor edit in the future when I'm not fighting germs!

Last edited:

Great chapter as always!Chiefs of the General Staff

Not that it matters, but there was a British General Staff OTL until 1904, at this point I think the Army was headed by the "Commander in Chief", and run from Horse Guards.

I just hope I'm getting the balance right! I tend to think that the more OTL things you can keep in unchanged, the more plausible and realistic the changes you do make in TTL feel. But that's just me, I'm sure others would feel differently.It is interesting going through this and seeing how much of this is still OTL and how much is changed in TTL...

Ah thankyou! And I blame this on my flu, I usually highlight things in red to be fact checked before I upload and this one got missed. I'll correct this, many thanks for highlighting it for me!Great chapter as always!

Not that it matters, but there was a British General Staff OTL until 1904, at this point I think the Army was headed by the "Commander in Chief", and run from Horse Guards.

By now were over twenty years passed our point of divergence, though, so entirely reasonable that any changes that occurred in the future in OTL could have already taken place here

Sort of agree but and it's a big but, the further from the POD the more things will naturally change if they are not being forced to follow OTL. British politics for instance will be very different after a time without Victoria and Albert, Disraeli is already different. People will have different attitudes without the Monarch going into mourning for as long. Marriages will start to differ so people will not be born or have the same upbringing, Victoria not being the grandmother of Europe for example will cause big ripples by 1900.I just hope I'm getting the balance right! I tend to think that the more OTL things you can keep in unchanged, the more plausible and realistic the changes you do make in TTL feel.

Oh absolutely, I agree but what I really meant was (again, flu brain!), I've tried thus far to pull at the strings a little more gently so that the changes that come later which really are very divergent from what happened in the OTL appear a little more natural - almost organic - but plausible because of the groundwork laid at this stage.Sort of agree but and it's a big but, the further from the POD the more things will naturally change if they are not being forced to follow OTL. British politics for instance will be very different after a time without Victoria and Albert, Disraeli is already different. People will have different attitudes without the Monarch going into mourning for as long. Marriages will start to differ so people will not be born or have the same upbringing, Victoria not being the grandmother of Europe for example will cause big ripples by 1900.

Great chapter! I’m glad that George is finally coming back to the public life. I’m glad Gladstone was able to survive the anti-Gladstone mob. And just a question, in 1842, the heir to the French throne died in July. It hasn’t been mentioned yet so I assume it happened ITTL as it did IOTL?

Thankyou so much!Great chapter! I’m glad that George is finally coming back to the public life. I’m glad Gladstone was able to survive the anti-Gladstone mob. And just a question, in 1842, the heir to the French throne died in July. It hasn’t been mentioned yet so I assume it happened ITTL as it did IOTL?

And yes, the Duke of Orléans still died in July 1842 ITTL, I hadn't mentioned it yet as it didn't seem to fit into our narrative neatly but it does provide us with a little plot point in the next chapter or two.

Threadmarks

View all 131 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

GV: Part Four, Chapter Five: Looking Away GV: Part Four, Chapter Six: Brothers and Sisters GV: Part Four, Chapter Seven: Mothers and Sisters GV: Part Four, Chapter Eight: An Answer to Prayer GV: Part Four, Chapter Nine: Kings and Successions GV: Part Four, Chapter Ten: Cat and Mouse GV: Part Four: Chapter Eleven: Secrets and Lies GV: Part Four, Chapter Twelve: Life at Lisson

Share: