Chapter 2: The Confederation of Cologne

Peace with the Hansa did not mean peace for Denmark, nor the north in General. With the threat to his south temporarily kept in check, Valdemar turned his attention to the new player in the north – Albert of Sweden. The Mecklenburger King naturally desired the return of the Scanian lands of recently reconquered by the Danes, as well as kicking out Haakon Magnusson out of western Sweden. Valdemar Atterdag however ostensibly supported his son-in-law, but clearly served his own interests first and foremost. Northern Halland, the last piece of the Scanian lands still in Swedish hands, and Gotland in which a local rebellion had thrown out the Danish bailiffs, were both taken by Danish forces. Not only that, but forces led by King Valdemar and Junker Christopher pushed deep into Swedish core territories, besieging the castle of Kalmar. If the castle fell, Albert’s connection to Mecklenburg would be severed, which would be disastrous as his rule over Sweden relied on support from his homeland.

Valdemar was known by his enemies as ‘the Wolf’ for his supposed cruelty, but in Mecklenburg there was a fox, Duke Albert the Elder; the father and puppet master of King Albert of Sweden. Seeing the dangerous situation his son was in, Duke Albert travelled to Denmark to negotiate peace on his behalf. The wolf and the fox would meet at the Castle of Aalholm in Lolland. The results of the “negotiations” became the Aalholm tractate, an unusually one-sided deal in which Albert recognized Gotland, Halland, as well as large parts of western Sweden supposedly controlled by Haakon of Norway as belonging to King Valdemar. In return, the Danish King simply promised to halt his invasion and that peace should reign between the two Kingdoms. It was agreed that this “eternal peace” should be ratified six months later at Brömsehus castle on the border between the Danish province of Blekinge and Swedish Småland. While the tractate rewarded Valdemar greatly, it essentially also broke his alliance to the captured Magnus Eriksson, and soured relations further with Haakon of Norway.

Peace had been hard bought for the Mecklenburgers, but already as the terms were written there must have been doubt from both Valdemar and Albert that either side would break it whenever the time proved favorable. Perhaps attempting to preemptively hinder this, Valdemar added a final demand; his son Christopher and Albert’s recently widowed daughter Ingeborg were to marry. Valdemar’s eldest daughter, also named Ingeborg, was already married to Albert’s son Henry ‘the Hangman’, though that had done little to end enmity between the two families. With a second joining of the families, Valdemar hoped to finally get the opportunistic Duke on his good side. Still unable to deny the King’s demands, Albert got his daughter to agree, and Ingeborg of Mecklenburg was married to Junker Christopher of Denmark in the summer of 1366.

Whilst war and peace happened in the north, there were diplomatic developments in the south. Valdemar Atterdag had long enjoyed a mutually beneficial relationship with Charles of Luxembourg, King of Bohemia and since 1355, Holy Roman Emperor. Charles was a visionary ruler, with grand plans for the Economy of his Empire and Europe in general. He envisioned a central European trade route that would stretch from Venice in the south to Lübeck in the north, with his capital of Prague as the natural central point. To achieve this would however require more control over the Hanseatic cities than the Emperor could boast of at the moment, and this was where Charles saw the use of Valdemar. A relatively strong and friendly Danish King could act as a counterbalance to the independence of the Hansa, and as such was a requirement for Charles’ trading dreams to come true. Valdemar’s recent victory had seemingly confirmed to the Emperor that he would act as his check on the league, the same year Charles ordered Lübeck to pay it’s imperial dues directly to the King, not himself. This sent a strong signal that Valdemar had the Emperor’s support.

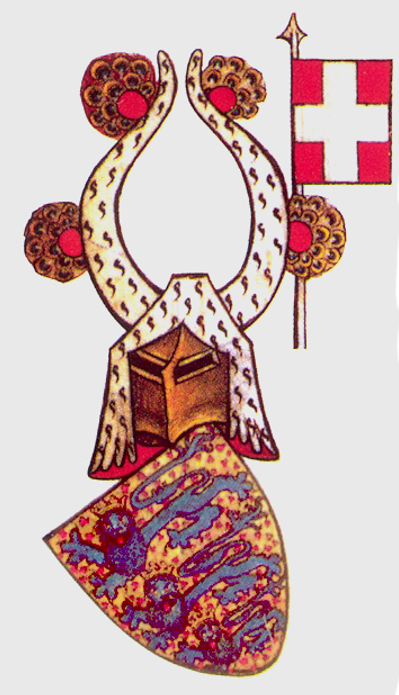

Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor, King of Bohemia, and good friend of Valdemar Atterdag.

Emperor or not, Valdemar still had many enemies close to home, the Counts of Holstein, the Hanseatic League as well as the Mecklenburgers – both those in Sweden and on the continent, neither of who intended to keep the eternal peace longer than necessary. At a meeting in the city of Cologne, 77 Hanseatic cities, as well as various northern German lords and dismayed Danish nobles formed a confederation, an alliance, specifically targeting King Valdemar. Though each group had separate goals, they all saw a common obstacle with a single way to overcome it; the wolf had to be hunted down. Some even specifically called for the head of the King, an almost sacrilegious act, monarchs were instated by the grace of God after all, but in this case, hatred overcame piety. But though the Confederation was on the warpath, Charles’ support for Valdemar caused them to hesitate, opposing their Emperor was nothing the allies were thrilled about.

The opportunity came in early 1368, when the Emperor left for Italy, it was now or never for the Confederation of Cologne. If they attacked and overwhelmed Valdemar before his benefactor could return, they were ready to bet that the ever-pragmatic Charles would see that he had bet on the wrong horse and withdraw his support. And so, as spring came, so did war return to the Kingdom of Denmark. Valdemar wasn’t scared however and mocked his enemies by declaring that “77 geese and 77 hens mean nothing…”, then placing a gilded goose at the top of the main tower of Vordingborg. The ensuing attack had two main prongs, forces from Holstein would invade Jutland while a Hanseatic fleet would move into the Øresund and seize the towns and castles on each side of the waters. Initially the attack was brutal and decisive, Danish defenses seemed to collapse all over against the tide of invaders. Unable to mount an effective defense, Danish forces sought refuge in any castle or fortress they could. While Valdemar himself left his Kingdom, journeying south to gather support in Germany, leaving Junker Christopher in command of the defense of the Kingdom.

After King Valdemar’s bold proclamation, the main tower of Vordingborg became known as “the Goose Tower”

There was one bright spot in the seemingly mounting disaster. In April of 1368, the Hanseatic fleet launched its assault on Copenhagen. The town and its castle were both key to dominate the Øresund and was rapidly growing to be the position from which Denmark could challenge Hanseatic dominance. Thus, the League found that there was only one fate fit for the town: it had to burn. Unlike the last time a Hanseatic fleet had sailed into the Øresund, its leader was no merchant prince raised to command of soldiers, but a veteran mercenary himself. Count Henry II of Holstein, son of Gerhard the Bald, had seen battle from Russia to France and earned himself the name “Iron Henry”. With him at the helm, the Hanseatic forces would surely crush the Danish opposition.

Yet, Copenhagen was also under skilled command, for it was here that Junker Christopher himself made his stand. Though half the age of the Iron Count, Christopher had been fighting at his father’s side since the moment he could grip a sword properly. Now, he would prove whether he was worthy of the great trust his father had put in him. Henry did not plan for Copenhagen to be taken by a lengthy siege, but rather by a simultaneous assault both from land and sea. The Count led from the front, intending to be the first man over the siege ladders. His initial attack breached the walls, but the opposition was thicker than anticipated. Christopher had strategically kept some of his ships at harbor, keeping them at key locations to slow down the naval assault. This move meant that the naval portion of the assault became a slow trickle, rather than a tidal wave sweeping all in front of it. Crucially, it also meant that more of the defenders of Copenhagen could be poised against the land assault, as they were not needed at sea.

The attack on Copenhagen, as imagined centuries later.

Even so, Henry and his assault was gaining ground and soon the Danes began to waver. Perhaps they had taken the Count’s name literally and believed their weapons useless against a man of metal, perhaps they had merely heard his fearsome reputation. In a desperate attempt to rally his men, Junker Christopher joined the fray, and with him the royal banner. This raised the stakes considerably, if the Iron Count could not only capture the city but also the King’s son, he could perhaps bait Valdemar out of hiding. Then he would surely have to give in to all their demands. Perhaps this distracted Henry, perhaps he became too focused on his new prize, or perhaps his decade-long kriegsglück simply ran out. A loss of footing would throw the Count off his feet, perhaps he even tripped over a man he himself had ended, but Iron Henry would crash to the ground in the heat of battle. Like a pack of starving hounds, the defenders of Copenhagen set upon him, stabbing, and cutting at any exposed mail or flesh. In an instant, the man who had inflicted so many wounds upon others became riddled with them himself, in the next instant he died.

Junker Christopher’s counterattack and the death of Count Henry created a shift in the tides of battle, fickle as they be, and soon the Danes were pushing the attackers back the way they came. The walls and grounds around Copenhagen would be littered with the bodies of the dead and dying, but as the violence calmed, it became clear that the town had held. Some of the retreating mercenaries would return to their landing points and attempt to make it back to their ships, while other scurried into the hinterlands of Zealand, where they would terrorize the local population for some time to come, but not pose a threat to any major Danish defenses. The Hanseatic fleet remained outside Copenhagen only briefly, before moving on to other less well-defended targets.

As the initial weeks of the war passed, it became clear that nothing was decided yet regarding it’s outcome.

“The Fortress of Absalon” had been built on the order of the legendary Warrior-Bishop and supposed founder of Copenhagen, it’s destruction had been a primary goal of the Hanseatic attack.