You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Fenians, Brits, Mexicans, Canucks and Frenchies....OH, MY! An alternate American Civil War

- Thread starter Alt History Buff

- Start date

Chapter 318

November 7th, 1905

20 miles east of New York Harbor

It would take Admiral Canevaro's aging eyes a few minutes longer than the younger officers to recognize the unfamiliar profile of the approaching vessel for being the only thing it could be: the new USS Michigan....which had not been expected to be seaworthy until the spring. However, the agents of France, Italy and Spain had underestimated the effect of President McKinley's demand for readiness over the past months. This had expedited the final fitting of the ship and the shakedown cruise.

The ship, under Captain Shafter, had largely proceeded through these tests smoothly and the Captain was ready to answer the call when orders came to speed north with all due urgency.

Shafter still doubted that any of the Europeans (he counted America's "ally" as European as the Captain never trusted the limeys again after their backstabbing in 1861) were really intent on shipping large numbers of heavy capital ships across an ocean (while they were otherwise occupied fighting one another) to attack what was still a neutral power. He was quite certain this was a little sortee to remind America of the Latin Alliance's power or just a round-about route to reinforce Cuba.

Encountering the light division of the Atlantic Fleet sailing south would put an end to this. Signals would be exchanged which explained the horrific defeat of the Atlantic squadron and the loss of at least three of the squadron's 10 capital ships. God only knew what the damned Europeans were doing to New York at the moment. They could have burned Manhattan and Brooklyn to the ground.

Filled with anger, the Captain soon realized that he was now in command of the combined fleet of 10 vessels which had no flag officer present and had no time whatsoever to coordinate an attack strategy in advance. Realizing the chaos that may result in overly complex maneuvers, Shafter would signal simple orders to the nine ships now in tow behind the Michigan.

The could not be simpler for the smaller vessels: advance in line until the order of "General Melee" was given. Then attack nearest vessel which does not outgun you.

That left the Michigan and the Iowa-class Montana, the only capital ships to his armada, to continue in line. The Montana's captain, a 30 year veteran, was unfortunately on leave in Texas having expected the Montana to be under repair and refurbishment for another month. His immediate subordinate was a 12 year veteran and new to the command. This was not the ideal situation on any level.

Since the alternative was for Shafter and his fleet to run away and abandon New York.....well, this was no alternative especially given that he commanded the most modern warship on earth....which was only 70% crewed by men who were unfamiliar with her.

Again, not an ideal situation.

But war seldom lent concessions to the unready and the sailor was determined that he and his makeshift fleet would account well of themselves.

After 24 hours of hard sailing, the fleet reached the mouth of New York Harbor and spied what he expected, at least 8 British vessels. Spotters verified the famous lines of the Cuniberto as well as two Seine-class (or was it Loire-class) heavy cruisers.

This, he realized, would be a hard fight.

Shafter had just ordered the fleet in line formation with the addendum that the lighter ships melee after one pass when one of the eight Latin Alliance ships rather spectacularly exploded.

"What the hell?" he muttered. It was one of the lighter ships, maybe a destroyer or frigate. Probably a fire from the previous day's battle had reached a powder room.

Putting it out of his head, Captain Shafter waited until his 13-inch guns reached their 5 mile ideal range and ordered his gunners to fire away.

Five miles north, Admiral Canevaro would watch in horror as the water spouts flew upwards only 200 yards shallow of the Cuniberto's position. He had been waiting until the enemy reached firing range (technically his guns COULD fire at such a distance but really were so inaccurate as to be not worth the ammunition).

Moments later, he heard the roar of the guns only now reaching his ears.

The American 13-inchers are really something. Only a minute earlier, he learned that the Seine was, indeed, unable to fight and that the Loire could fight but was likely reduced to 10 kph of speed. Against his will, he gave the order he had to give. The Cuniberto and Esmerelda would engage the Americans while the other five ships would retreat directly east.

With a heavy heart he ordered his fleet into battle as the two most powerful ships on earth collided at range. The Cuniberto's captain had spent much of the past day berating his gunners for their poor performance the previous day. Indeed, there was some question if a single shell from the Italian behemoth's 12-inch cannon struck a single enemy ship. The French Loire and Seine, however, had managed at least half a dozen hits. Embarrassed, the Italians desired to regain their honor.

Honor was certainly on hand as the two ships passed two miles apart, each to the other's starboard, only striking/sustaining/exchanging hits when nearly parallel. Both ships rocked. The Cuniberto lost another turret while the aft deck of the Michigan sustained a hit hard enough to knock out men in the engine compartment. Passing, the lead vessels turned their attention on the trailing ships.

The Michigan would have the easier time of the two as the older, lighter Esmerelda would frantically fire her 8 inch guns, barely spraying the Michigan with her near misses. The Michigan, on the other hand, would fire both of her fore-turrets, missing long and short. The aft turret, however, landed amidships the Spanish vessel tearing through her superstructure. While the engines had not been damaged, the rest of the ship had suffered catastrophically. The command deck was gone, both fore and aft guns out of commission and massive fires springing up as fire crews discovered no pressure on their lines. The Esmerelda just kept chugging forward unaware she was already dead.

The Cuniberto, now down two of their six turrets (and half of those which could actually rotate to starboard. Still reeling from the tooth-cracking blow from the Michigan, the Italian guns missed by over 200 yards and the Iowa-Class Montana would put two more shells upon the Cuniberto's deck.

Moment's later, the Italian Admiral would order the Cuniberto to circle about to the east (the Atlantic side) in order to provide more cover to the retreating fleet.

For his part, Captain Shafter was stunned to see most of the enemy ships steaming out to sea, some obviously well below listed maximum speed. Did Dewey hurt them THAT much?

The American sailor did not hesitate. He signaled an early "General Melee" and steamed directly after the retreating Latin Alliance ships. In less than 20 minutes, the van of the American fleet was catching up to the stragglers. The commander of the Montana would take the initiative to engage the Cuniberto and prevent her from rejoining the rest of the fleet.

The Loire and Seine (Shafter did not know which was which) would be the first caught. One was obviously listing to the side. The fore-guns of the Michigan would key in on that one which ceased firing after several obviously failed attempts to level her own aft turrets. The first shell would pierce near the vessel's aft of the Seine, the engines would nearly vibrate to a stop before managing to regain power. But it was too late, the Michigan's guns again found the range, this time landing upon the aft deck, causing carnage and costing the Seine her useless aft turrets. Finally the engines blew in an audible explosion but not before another shell pierced the superstructure killing the command crew. With fires springing up, the Seine's surviving senior officer would strike her colors.

The Michigan would not even slow. Instead, she would seize upon the next of the French ships, this time the lumbering Loire. The Loire had suffered two torpedo hits. However, they were on opposite sides and this somewhat mitigated the hindrance on steering, if not speed. Also, since the French were able to flood compartments on each side, the allowed the vessel to remain stable and therefore able to fight back. Unfortunately, one of the Loire's two main turrets had been hit....the aft turret. Knowing he could not outrun the Americans, the French captain turned his vessel to charge forward with his remaining twin 12-inch gun turret (fore).

The Michigan would take her second hit, a glancing blow off her starboard deck. Dozens of sailors were killed but the guns and engines remained in service. Beyond some minor leakage, the ship remained functional. After several misses by the somewhat green gunners still learning the weapons, the Michigan finally found her range at only 800 yards. The superstructure of the Loire practically disintegrated. Like the Esmerelda, the vessel continued forward without any active command. The Michigan's aft weapons would put two shells into the vessel's hull, effectively ending the battle as the proud French ship began listing badly. The French flag was struck by whoever was left alive.

In the meantime, the light division would catch up the old, slow and damaged Spanish cruiser Infante. Though the Spanish ship outgunned the smaller American vessels, soon she was being bracketed in by rounds from four ships.

Just as it appeared she might get away, the engines took the occasion to give way. The Infante slowed to a dead stop and the mobile Americans began circling like sharks. After taking three hits, the Spanish commander opted to surrender his vessel when he realized he was down to but one set of guns.

10 miles further east, the Cuniberto continued to duel with the Montana, both ships receiving hits. Finally, enough smoke cleared for the Italian commander to realize that most of his fleet was gone. Having sustained at least nine strikes in the past 32 hours, Admiral Canevaro had had enough. He ordered his Captain to turn eastwards towards the open sea. The Montana, equally beat up, would wisely determine not to follow.

It would be another two weeks before the Admiral knew exactly what was left of the proud 16 ship fleet which had sailed so proudly to America. Beyond the Cuniberto, only the French Frigate Desperaux and French Corvette Orleans had managed to return to Cadiz. 13 of the 16 ships had been lost. That the American Atlantic fleet had been similarly bloodied would be cold consolation.

Worse, Canevaro realized that his mission had failed in its principle objective: remove America from active and efficient contribution to the British-German war effort.

Rather than intimidate and humiliate, the Latin Alliance had only managed to enrage.

20 miles east of New York Harbor

It would take Admiral Canevaro's aging eyes a few minutes longer than the younger officers to recognize the unfamiliar profile of the approaching vessel for being the only thing it could be: the new USS Michigan....which had not been expected to be seaworthy until the spring. However, the agents of France, Italy and Spain had underestimated the effect of President McKinley's demand for readiness over the past months. This had expedited the final fitting of the ship and the shakedown cruise.

The ship, under Captain Shafter, had largely proceeded through these tests smoothly and the Captain was ready to answer the call when orders came to speed north with all due urgency.

Shafter still doubted that any of the Europeans (he counted America's "ally" as European as the Captain never trusted the limeys again after their backstabbing in 1861) were really intent on shipping large numbers of heavy capital ships across an ocean (while they were otherwise occupied fighting one another) to attack what was still a neutral power. He was quite certain this was a little sortee to remind America of the Latin Alliance's power or just a round-about route to reinforce Cuba.

Encountering the light division of the Atlantic Fleet sailing south would put an end to this. Signals would be exchanged which explained the horrific defeat of the Atlantic squadron and the loss of at least three of the squadron's 10 capital ships. God only knew what the damned Europeans were doing to New York at the moment. They could have burned Manhattan and Brooklyn to the ground.

Filled with anger, the Captain soon realized that he was now in command of the combined fleet of 10 vessels which had no flag officer present and had no time whatsoever to coordinate an attack strategy in advance. Realizing the chaos that may result in overly complex maneuvers, Shafter would signal simple orders to the nine ships now in tow behind the Michigan.

The could not be simpler for the smaller vessels: advance in line until the order of "General Melee" was given. Then attack nearest vessel which does not outgun you.

That left the Michigan and the Iowa-class Montana, the only capital ships to his armada, to continue in line. The Montana's captain, a 30 year veteran, was unfortunately on leave in Texas having expected the Montana to be under repair and refurbishment for another month. His immediate subordinate was a 12 year veteran and new to the command. This was not the ideal situation on any level.

Since the alternative was for Shafter and his fleet to run away and abandon New York.....well, this was no alternative especially given that he commanded the most modern warship on earth....which was only 70% crewed by men who were unfamiliar with her.

Again, not an ideal situation.

But war seldom lent concessions to the unready and the sailor was determined that he and his makeshift fleet would account well of themselves.

After 24 hours of hard sailing, the fleet reached the mouth of New York Harbor and spied what he expected, at least 8 British vessels. Spotters verified the famous lines of the Cuniberto as well as two Seine-class (or was it Loire-class) heavy cruisers.

This, he realized, would be a hard fight.

Shafter had just ordered the fleet in line formation with the addendum that the lighter ships melee after one pass when one of the eight Latin Alliance ships rather spectacularly exploded.

"What the hell?" he muttered. It was one of the lighter ships, maybe a destroyer or frigate. Probably a fire from the previous day's battle had reached a powder room.

Putting it out of his head, Captain Shafter waited until his 13-inch guns reached their 5 mile ideal range and ordered his gunners to fire away.

Five miles north, Admiral Canevaro would watch in horror as the water spouts flew upwards only 200 yards shallow of the Cuniberto's position. He had been waiting until the enemy reached firing range (technically his guns COULD fire at such a distance but really were so inaccurate as to be not worth the ammunition).

Moments later, he heard the roar of the guns only now reaching his ears.

The American 13-inchers are really something. Only a minute earlier, he learned that the Seine was, indeed, unable to fight and that the Loire could fight but was likely reduced to 10 kph of speed. Against his will, he gave the order he had to give. The Cuniberto and Esmerelda would engage the Americans while the other five ships would retreat directly east.

With a heavy heart he ordered his fleet into battle as the two most powerful ships on earth collided at range. The Cuniberto's captain had spent much of the past day berating his gunners for their poor performance the previous day. Indeed, there was some question if a single shell from the Italian behemoth's 12-inch cannon struck a single enemy ship. The French Loire and Seine, however, had managed at least half a dozen hits. Embarrassed, the Italians desired to regain their honor.

Honor was certainly on hand as the two ships passed two miles apart, each to the other's starboard, only striking/sustaining/exchanging hits when nearly parallel. Both ships rocked. The Cuniberto lost another turret while the aft deck of the Michigan sustained a hit hard enough to knock out men in the engine compartment. Passing, the lead vessels turned their attention on the trailing ships.

The Michigan would have the easier time of the two as the older, lighter Esmerelda would frantically fire her 8 inch guns, barely spraying the Michigan with her near misses. The Michigan, on the other hand, would fire both of her fore-turrets, missing long and short. The aft turret, however, landed amidships the Spanish vessel tearing through her superstructure. While the engines had not been damaged, the rest of the ship had suffered catastrophically. The command deck was gone, both fore and aft guns out of commission and massive fires springing up as fire crews discovered no pressure on their lines. The Esmerelda just kept chugging forward unaware she was already dead.

The Cuniberto, now down two of their six turrets (and half of those which could actually rotate to starboard. Still reeling from the tooth-cracking blow from the Michigan, the Italian guns missed by over 200 yards and the Iowa-Class Montana would put two more shells upon the Cuniberto's deck.

Moment's later, the Italian Admiral would order the Cuniberto to circle about to the east (the Atlantic side) in order to provide more cover to the retreating fleet.

For his part, Captain Shafter was stunned to see most of the enemy ships steaming out to sea, some obviously well below listed maximum speed. Did Dewey hurt them THAT much?

The American sailor did not hesitate. He signaled an early "General Melee" and steamed directly after the retreating Latin Alliance ships. In less than 20 minutes, the van of the American fleet was catching up to the stragglers. The commander of the Montana would take the initiative to engage the Cuniberto and prevent her from rejoining the rest of the fleet.

The Loire and Seine (Shafter did not know which was which) would be the first caught. One was obviously listing to the side. The fore-guns of the Michigan would key in on that one which ceased firing after several obviously failed attempts to level her own aft turrets. The first shell would pierce near the vessel's aft of the Seine, the engines would nearly vibrate to a stop before managing to regain power. But it was too late, the Michigan's guns again found the range, this time landing upon the aft deck, causing carnage and costing the Seine her useless aft turrets. Finally the engines blew in an audible explosion but not before another shell pierced the superstructure killing the command crew. With fires springing up, the Seine's surviving senior officer would strike her colors.

The Michigan would not even slow. Instead, she would seize upon the next of the French ships, this time the lumbering Loire. The Loire had suffered two torpedo hits. However, they were on opposite sides and this somewhat mitigated the hindrance on steering, if not speed. Also, since the French were able to flood compartments on each side, the allowed the vessel to remain stable and therefore able to fight back. Unfortunately, one of the Loire's two main turrets had been hit....the aft turret. Knowing he could not outrun the Americans, the French captain turned his vessel to charge forward with his remaining twin 12-inch gun turret (fore).

The Michigan would take her second hit, a glancing blow off her starboard deck. Dozens of sailors were killed but the guns and engines remained in service. Beyond some minor leakage, the ship remained functional. After several misses by the somewhat green gunners still learning the weapons, the Michigan finally found her range at only 800 yards. The superstructure of the Loire practically disintegrated. Like the Esmerelda, the vessel continued forward without any active command. The Michigan's aft weapons would put two shells into the vessel's hull, effectively ending the battle as the proud French ship began listing badly. The French flag was struck by whoever was left alive.

In the meantime, the light division would catch up the old, slow and damaged Spanish cruiser Infante. Though the Spanish ship outgunned the smaller American vessels, soon she was being bracketed in by rounds from four ships.

Just as it appeared she might get away, the engines took the occasion to give way. The Infante slowed to a dead stop and the mobile Americans began circling like sharks. After taking three hits, the Spanish commander opted to surrender his vessel when he realized he was down to but one set of guns.

10 miles further east, the Cuniberto continued to duel with the Montana, both ships receiving hits. Finally, enough smoke cleared for the Italian commander to realize that most of his fleet was gone. Having sustained at least nine strikes in the past 32 hours, Admiral Canevaro had had enough. He ordered his Captain to turn eastwards towards the open sea. The Montana, equally beat up, would wisely determine not to follow.

It would be another two weeks before the Admiral knew exactly what was left of the proud 16 ship fleet which had sailed so proudly to America. Beyond the Cuniberto, only the French Frigate Desperaux and French Corvette Orleans had managed to return to Cadiz. 13 of the 16 ships had been lost. That the American Atlantic fleet had been similarly bloodied would be cold consolation.

Worse, Canevaro realized that his mission had failed in its principle objective: remove America from active and efficient contribution to the British-German war effort.

Rather than intimidate and humiliate, the Latin Alliance had only managed to enrage.

Hail to the Victors Valiant! Hail to the Conquering Heroes of the USS Michigan and her brave companions!

Surrounded by the US which will be aligned with the UK?And Canada?

I expect that both the US and the UK would be happy to take foreign fighters. Think the US soldiers joining the UK in OTL 1939-1941.Even more neutral.

Chapter 319

November 15, 1905

Washington

President McKinley would repeat what the bodies of Congress already knew: the details of the nefarious sneak attack on the Atlantic Fleet and New York Harbor.

What McKinley did NOT really going into depth was how lucky the nation was that the Latin Alliance had been spotted and given two days to prepare. Had they not......?

Not only would the Americans lose most of the Atlantic fleet but possibly see New York burned to the ground as well.

However, the call to war....in which even the opposition was obliged to agree lest they be painted an unpatriotic....mixed with despair at the grievous losses to the United States Navy even before a formal vote be summoned. Naval experts like Admiral Mahan (the Secretary of the Navy) would point out the nation had actually done quite well given the circumstances. Most of the enemy fleet had been wiped out including two of the most modern French ships (in today's world, only the most modern ships mattered, the rest mainly filling out the ranks). But Americans, like most people, viewed their own losses as more devastating than what the enemy sacrifices.

Mahan would review the situation and, while grieving for the lost sailors and ships, knew that the Latin Alliance had suffered badly too. Already heavily invested against the British, the Admiral would not have expected the Latin Alliance to gamble so many ships against a nominally "neutral" power (though even Mahan had to admit his nation's support of Great Britain and, by proxy, Germany, stretched the long-established standards of "neutral"). It had been a daring maneuver that Mahan would doubt any nation, much less a coalition of three, would take. Privately, he admired the Alliance for their courage if not their wisdom.

The Admiral understood the viewpoint of the Latin Alliance, strike first before America enters under HER terms. But Mahan believed this was a mistake nonetheless. Yes, crippling the Atlantic fleet and....presumably....engaging in unrestricted commerce raiding of American merchant ships would certainly reduce American effectiveness in the near term. However, the outrage spreading throughout America like a flame would, in the long run, do the Latin Alliance no favors. There would be few voices of dissent as the manpower, wealth and resources of America were applied with full force against the Latin Alliance.

McKinley finished his speech to widespread applause (even the Democrats knew they had to at least half-heartedly clap) and nodded for Mahan to follow him out.

The President would shake a number of hands, of course, and accept the backslapping of supporters before leaving Congress to debate the Declaration of War. No doubt it would come quickly.

Returning to the Presidential Mansion, McKinley would meet with his key cabinet members including Mahan, the Secretary of War, William Howard Taft, Admiral Wainwright and the Commanding-General of the Army, Hugh L. Scott.

These were all good men, McKinley thought, all soldiers save Taft, who was a highly talented administrator.

Sitting behind his desk, McKinley gestured for his advisors to sit and demanded, "Well, Gentlemen, how can we strike back and I mean hard and fast?"

Wainwright shook his head, "We got lucky......damned lucky.....that those torpedoes proved so effective else we'd be sifting through the ashes of the Brooklyn Naval Yard and possibly most of New York right now. "

"True," McKinley agreed, "but not relevant. HOW DO WE STRIKE BACK HARD AND FAST?"

Taft answered, "The Atlantic fleet is severely weakened. Another such attack by the Latin Alliance....."

"Will NOT be happening," Mahan interrupted with certainty. "The Alliance intended this to be a one-time knockout blow. Even this was a monumental risk of evading the British. While our scandal rags have been decrying for days the state of our brave Atlantic fleet, the truth is that the Latins failed in their objectives as I am sure laying waste to New York and the Brooklyn shipyards was the plan to cripple America going forward. And don't underestimate the losses taken by the Alliance. Already at war with the preeminent naval power of the past 200 years, the enemy....assuming the Declaration of War is quickly approved.....have lost many of their best ships against what had been a neutral party. There has yet to be even a major battle at sea against the British and the Latins have already suffered terribly."

"No, Mr. President," Mahan concluded, "I am not concerned with a followup attack on New York or anywhere else along the coast in the near future."

Wainwright though about this for a moment and nodded his concurrence. That was enough for McKinley.

"And then back to my original question.....HOW DO WE HIT BACK HARD AND FAST?!"

Surprisingly, Taft replied, "There is only one real option. Cuba. It is closeby and we would have the use of the West Indian Squadron. As best we can tell, the Alliance hasn't strengthened the garrison or augmented the Spanish West Indian Fleet which, I understand, is even less capable than the Spanish European Squadron."

Wainwright and Mahan both nodded their agreement.

"Then I propose that we utilize those Volunteers we've been training for the past year, plus whatever regulars we can spare, and pit them against the Spanish in Cuba."

General Scott, somewhat younger than the typical commanding-General, would sigh and finally weigh in, "In truth, Mr. President, there is nothing an officer hates more than sending his men into a pestilential hell. Unlike the Colombian Canal Area, Cuba has NOT been significantly cleared of swamps. Malaria and Yellow Fever are endemic despite several doctors on the island being instrumental in discovering the treatment and prevention of those dreaded diseases. If we send an army to Cuba, it will suffer terribly. But I must concur that this is the only reasonable action at the moment short of shipping soldiers to Germany....which I gather is politically unpalatable at the moment."

McKinley agreed, "Yes, that will be a discussion for the Spring. We've had no talks with the Germans as yet and I cannot even begin to think what the American people will think if THAT idea. For now, we must restrict ourselves to formalizing our alliance with Britain, supplying Britain and Germany with war material and grain, hitting Latin Alliance shipping and attacking targets within reach.....like Cuba."

"Will this be a conquest of Cuba," Taft interjected, "or a liberation."

McKinley knew this was a difficult question. For years, American papers had endorsed the independence movements of the Cubans and Puerto Ricans (and to a lesser extend the Hispaniolans) against a savage oppressor. Would America seek to simply replace that oppressor?

The President shook his head, "I do not believe that we can rally support so easily just for a blatant land grab. I prefer to take the high road and support "Freedom" with an eye for offering a place in our nation to the Cubans et all...via choice. Honestly, I think that may be in the best interests of the Spanish colonials though who knows if that would be a major consideration. Spain has spent years attempting to put down rebellions. I don't want to condemn this country to doing the same especially given the linguistic and religious factors in play. Evicting yet another European nation completely from the Americas would be a good enough outcome of this war and doing so in a way to help a new Republican neighbor in the West Indies.....who would naturally look at a map and know who runs the neighborhood.....would make the most sense."

"But there is no reason to commit to anything yet....."

"Mr. President," Taft interjected again, "what of the Latin Alliance's.....friendship.....with Brazil and Chile? Should we not make preparations for war in the Amazon as well?"

By happenstance, Secretary of State John Hay would be rushed into McKinley's office a moment later. Hay had been invited to the meeting as well and the President was irritated by his absence. Hay carried a bushel of papers in his hand and didn't bother with any formal greetings to the assembled dignitaries.

"Mr. President, I apologize for my tardiness but rather important documents have been given to my staff. I took some time to review before arriving here."

The Secretary of State would hand them to McKinley across the desk. The President noted they were in Portuguese.

"And these documents......?" He prompted, fearing he knew the answer.

"A Declaration of War upon us by the Empire of Brazil."

"Naturally, Hay, naturally."

Washington

President McKinley would repeat what the bodies of Congress already knew: the details of the nefarious sneak attack on the Atlantic Fleet and New York Harbor.

What McKinley did NOT really going into depth was how lucky the nation was that the Latin Alliance had been spotted and given two days to prepare. Had they not......?

Not only would the Americans lose most of the Atlantic fleet but possibly see New York burned to the ground as well.

However, the call to war....in which even the opposition was obliged to agree lest they be painted an unpatriotic....mixed with despair at the grievous losses to the United States Navy even before a formal vote be summoned. Naval experts like Admiral Mahan (the Secretary of the Navy) would point out the nation had actually done quite well given the circumstances. Most of the enemy fleet had been wiped out including two of the most modern French ships (in today's world, only the most modern ships mattered, the rest mainly filling out the ranks). But Americans, like most people, viewed their own losses as more devastating than what the enemy sacrifices.

Mahan would review the situation and, while grieving for the lost sailors and ships, knew that the Latin Alliance had suffered badly too. Already heavily invested against the British, the Admiral would not have expected the Latin Alliance to gamble so many ships against a nominally "neutral" power (though even Mahan had to admit his nation's support of Great Britain and, by proxy, Germany, stretched the long-established standards of "neutral"). It had been a daring maneuver that Mahan would doubt any nation, much less a coalition of three, would take. Privately, he admired the Alliance for their courage if not their wisdom.

The Admiral understood the viewpoint of the Latin Alliance, strike first before America enters under HER terms. But Mahan believed this was a mistake nonetheless. Yes, crippling the Atlantic fleet and....presumably....engaging in unrestricted commerce raiding of American merchant ships would certainly reduce American effectiveness in the near term. However, the outrage spreading throughout America like a flame would, in the long run, do the Latin Alliance no favors. There would be few voices of dissent as the manpower, wealth and resources of America were applied with full force against the Latin Alliance.

McKinley finished his speech to widespread applause (even the Democrats knew they had to at least half-heartedly clap) and nodded for Mahan to follow him out.

The President would shake a number of hands, of course, and accept the backslapping of supporters before leaving Congress to debate the Declaration of War. No doubt it would come quickly.

Returning to the Presidential Mansion, McKinley would meet with his key cabinet members including Mahan, the Secretary of War, William Howard Taft, Admiral Wainwright and the Commanding-General of the Army, Hugh L. Scott.

These were all good men, McKinley thought, all soldiers save Taft, who was a highly talented administrator.

Sitting behind his desk, McKinley gestured for his advisors to sit and demanded, "Well, Gentlemen, how can we strike back and I mean hard and fast?"

Wainwright shook his head, "We got lucky......damned lucky.....that those torpedoes proved so effective else we'd be sifting through the ashes of the Brooklyn Naval Yard and possibly most of New York right now. "

"True," McKinley agreed, "but not relevant. HOW DO WE STRIKE BACK HARD AND FAST?"

Taft answered, "The Atlantic fleet is severely weakened. Another such attack by the Latin Alliance....."

"Will NOT be happening," Mahan interrupted with certainty. "The Alliance intended this to be a one-time knockout blow. Even this was a monumental risk of evading the British. While our scandal rags have been decrying for days the state of our brave Atlantic fleet, the truth is that the Latins failed in their objectives as I am sure laying waste to New York and the Brooklyn shipyards was the plan to cripple America going forward. And don't underestimate the losses taken by the Alliance. Already at war with the preeminent naval power of the past 200 years, the enemy....assuming the Declaration of War is quickly approved.....have lost many of their best ships against what had been a neutral party. There has yet to be even a major battle at sea against the British and the Latins have already suffered terribly."

"No, Mr. President," Mahan concluded, "I am not concerned with a followup attack on New York or anywhere else along the coast in the near future."

Wainwright though about this for a moment and nodded his concurrence. That was enough for McKinley.

"And then back to my original question.....HOW DO WE HIT BACK HARD AND FAST?!"

Surprisingly, Taft replied, "There is only one real option. Cuba. It is closeby and we would have the use of the West Indian Squadron. As best we can tell, the Alliance hasn't strengthened the garrison or augmented the Spanish West Indian Fleet which, I understand, is even less capable than the Spanish European Squadron."

Wainwright and Mahan both nodded their agreement.

"Then I propose that we utilize those Volunteers we've been training for the past year, plus whatever regulars we can spare, and pit them against the Spanish in Cuba."

General Scott, somewhat younger than the typical commanding-General, would sigh and finally weigh in, "In truth, Mr. President, there is nothing an officer hates more than sending his men into a pestilential hell. Unlike the Colombian Canal Area, Cuba has NOT been significantly cleared of swamps. Malaria and Yellow Fever are endemic despite several doctors on the island being instrumental in discovering the treatment and prevention of those dreaded diseases. If we send an army to Cuba, it will suffer terribly. But I must concur that this is the only reasonable action at the moment short of shipping soldiers to Germany....which I gather is politically unpalatable at the moment."

McKinley agreed, "Yes, that will be a discussion for the Spring. We've had no talks with the Germans as yet and I cannot even begin to think what the American people will think if THAT idea. For now, we must restrict ourselves to formalizing our alliance with Britain, supplying Britain and Germany with war material and grain, hitting Latin Alliance shipping and attacking targets within reach.....like Cuba."

"Will this be a conquest of Cuba," Taft interjected, "or a liberation."

McKinley knew this was a difficult question. For years, American papers had endorsed the independence movements of the Cubans and Puerto Ricans (and to a lesser extend the Hispaniolans) against a savage oppressor. Would America seek to simply replace that oppressor?

The President shook his head, "I do not believe that we can rally support so easily just for a blatant land grab. I prefer to take the high road and support "Freedom" with an eye for offering a place in our nation to the Cubans et all...via choice. Honestly, I think that may be in the best interests of the Spanish colonials though who knows if that would be a major consideration. Spain has spent years attempting to put down rebellions. I don't want to condemn this country to doing the same especially given the linguistic and religious factors in play. Evicting yet another European nation completely from the Americas would be a good enough outcome of this war and doing so in a way to help a new Republican neighbor in the West Indies.....who would naturally look at a map and know who runs the neighborhood.....would make the most sense."

"But there is no reason to commit to anything yet....."

"Mr. President," Taft interjected again, "what of the Latin Alliance's.....friendship.....with Brazil and Chile? Should we not make preparations for war in the Amazon as well?"

By happenstance, Secretary of State John Hay would be rushed into McKinley's office a moment later. Hay had been invited to the meeting as well and the President was irritated by his absence. Hay carried a bushel of papers in his hand and didn't bother with any formal greetings to the assembled dignitaries.

"Mr. President, I apologize for my tardiness but rather important documents have been given to my staff. I took some time to review before arriving here."

The Secretary of State would hand them to McKinley across the desk. The President noted they were in Portuguese.

"And these documents......?" He prompted, fearing he knew the answer.

"A Declaration of War upon us by the Empire of Brazil."

"Naturally, Hay, naturally."

Chapter 320

November20th , 1905

Manaus

Supplied by the newly extended Railroads north through the Amazon, a Brazilian force would cross the River into American territory and seize the inland city once the center of the Rubber Boom.

By 1905, the Brazilians had managed to find other routes of transportation to get their rubber out of the Andes Mountain regions but the loss of so much Brazilian territory, though to be honest this was the least valuable by any reckoning, had stuck in the collective Brazilian craw like a sharp chicken bone. Assured that the American fleet would be wiped out in early November, the Brazilians would act without hesitation. They did not expect a significant fight as the Americans, who had failed to colonize the region in the past 10 years, had also withdrawn most of their forces.

Manaus itself held fewer than 2000 American soldiers and was more of an administration center than fortification. 6000 Brazilian soldiers would cross the river and surround the low-lying city bereft of any natural defenses. The Americans quickly attempted to dig in but, beyond a few trenches, this quickly became an open battle. Brazilian shells soon set most of the city on fire, the extravagant townhouses built by rubber barons among the first to go. Little by little, the unprepared American forces were pushed back into the city center while another 2000 Brazilians set foot upon the northern shore the following day.

Ireland

News of the first formal "draft" into the army in British history would not go over well in some areas of Britain. In Ireland, there was a widespread rebellion as "recruiting officers" were ambushed in the streets, barracks were bombed and no British soldier dared go out in groups less than 20.

While the formal suspension of the "draft" in Ireland would be months away, in all reality it had ended the day it was announced.

By 1905, over 75,000 British troops were forced to occupy the island and most of the Loyalist residents were instead funneled into "police" actions to maintain British control over the island.

New York

Though Irish-Americans were outraged at the attack on New York as any other, the fact was that many Irish Catholics could simply not stand the idea of allying with the British on ANYTHING. It was bad enough that their chosen new home worked in conjunction with Britain over the Co-Protectorate.....but declaring war on their behalf too?

That was too much. Unlike previous wars, the Irish of New York, Boston and elsewhere would NOT flock to the colors. Increased German enthusiasm, on the other hand, would see a marked increase in German volunteers.

London

Prime Minister Arthur Balfour was nothing short of delighted. Any American reservations on supplying war material to Britain just evaporated. No doubt they would supply anything in any quantities. More directly, the Americans had apparently bled the Latin Alliance fleet quite badly. There had been fear that the combined fleets may challenge Britain on the the high seas.

If the poor performance of the allies was any indication, perhaps the Latins were not so great a threat as some appeared to believe.

Kyoto

The Japanese Army General Staff would meet over the winter of 1905/06 and debate what they should do, if anything, related to the war occupying Europe.

Some advocated seizing some of the British islands to the south, especially Borneo. Others wanted to fight a land campaign in Southeast Asia.

Others wanted to teach the Russians or Americans or Chinese a lesson after the embarrassing end to the previous war.

The debate would continue. In the meantime, the Navy General Staff would hold similar discussions and both Army and Navy approached the Emperor and his Ministers for support.

Manaus

Supplied by the newly extended Railroads north through the Amazon, a Brazilian force would cross the River into American territory and seize the inland city once the center of the Rubber Boom.

By 1905, the Brazilians had managed to find other routes of transportation to get their rubber out of the Andes Mountain regions but the loss of so much Brazilian territory, though to be honest this was the least valuable by any reckoning, had stuck in the collective Brazilian craw like a sharp chicken bone. Assured that the American fleet would be wiped out in early November, the Brazilians would act without hesitation. They did not expect a significant fight as the Americans, who had failed to colonize the region in the past 10 years, had also withdrawn most of their forces.

Manaus itself held fewer than 2000 American soldiers and was more of an administration center than fortification. 6000 Brazilian soldiers would cross the river and surround the low-lying city bereft of any natural defenses. The Americans quickly attempted to dig in but, beyond a few trenches, this quickly became an open battle. Brazilian shells soon set most of the city on fire, the extravagant townhouses built by rubber barons among the first to go. Little by little, the unprepared American forces were pushed back into the city center while another 2000 Brazilians set foot upon the northern shore the following day.

Ireland

News of the first formal "draft" into the army in British history would not go over well in some areas of Britain. In Ireland, there was a widespread rebellion as "recruiting officers" were ambushed in the streets, barracks were bombed and no British soldier dared go out in groups less than 20.

While the formal suspension of the "draft" in Ireland would be months away, in all reality it had ended the day it was announced.

By 1905, over 75,000 British troops were forced to occupy the island and most of the Loyalist residents were instead funneled into "police" actions to maintain British control over the island.

New York

Though Irish-Americans were outraged at the attack on New York as any other, the fact was that many Irish Catholics could simply not stand the idea of allying with the British on ANYTHING. It was bad enough that their chosen new home worked in conjunction with Britain over the Co-Protectorate.....but declaring war on their behalf too?

That was too much. Unlike previous wars, the Irish of New York, Boston and elsewhere would NOT flock to the colors. Increased German enthusiasm, on the other hand, would see a marked increase in German volunteers.

London

Prime Minister Arthur Balfour was nothing short of delighted. Any American reservations on supplying war material to Britain just evaporated. No doubt they would supply anything in any quantities. More directly, the Americans had apparently bled the Latin Alliance fleet quite badly. There had been fear that the combined fleets may challenge Britain on the the high seas.

If the poor performance of the allies was any indication, perhaps the Latins were not so great a threat as some appeared to believe.

Kyoto

The Japanese Army General Staff would meet over the winter of 1905/06 and debate what they should do, if anything, related to the war occupying Europe.

Some advocated seizing some of the British islands to the south, especially Borneo. Others wanted to fight a land campaign in Southeast Asia.

Others wanted to teach the Russians or Americans or Chinese a lesson after the embarrassing end to the previous war.

The debate would continue. In the meantime, the Navy General Staff would hold similar discussions and both Army and Navy approached the Emperor and his Ministers for support.

Chapter 321

December, 1905

New Jersey - camp for 1st Brigade, New York Volunteers

General of Volunteers Theodore Roosevelt had been granted a Brigade (three Regiments) and had been given leave to raise officers up to junior Lieutenant. The US Army had been long moving away from allowing high-ranking gentlemen to military command based on social status. This had been necessary in the Civil War but the large number of graduates from West Point over the past decades, US Army policy of being "officer heavy" and other strategy would ensure that most units could be organized by experienced men.

Roosevelt had, of course, served in Africa (for the Co-Protectorate) and in Brazil. Being a Republican Senator also helped. But Roosevelt would NOT be given leave to raise dozens to hundreds of men to officer ranks. Instead, officers were transferred from other units, from the reserve list, from regional militias and directly from West Point. But Roosevelt would be able to "recommend" some junior officer commissions which included his friend Winston Churchill and his kinsmen Tadd Roosevelt and Franklin Roosevelt.

By happenstance, an engineering battalion would be assigned to the 1st Brigade which included Churchill's younger brother, senior Lieutenant Jack Churchill as well.

Also attached to the Regiment would be a battalion of light artillery pieces.

Having resigned from the Senate as he expected war to be broken out at any point, the General wanted to be at the forefront of battle. With 5000 (mostly New Yorkers) good men under arms and with months of training (something volunteers in previous American wars seldom received), Roosevelt was anxious to get off to war. He preferred Cuba as his service in Brazil had been disappointing.

However, Roosevelt would NOT be pleased to learn that his 1st New York Volunteers would be placed under command of a regular officer, Brigadier General John Pershing. Roosevelt considered his experience superior to Pershing but the two would eventually forge a good working relationship over the past few months as Pershing realized that Roosevelt was not a dilatant looking for glory without doing the work.

Though outraged by the Latin Alliance attack on New York, Roosevelt was excited at the prospect of finally being back in battle.

Pershing and Roosevelt would be ordered to Washington to coordinate the formation of a full army of Volunteers and Regulars.

Eastern Poland

Having expected a quick collapse of the Germans, the Czarina would spend much of the fall berating her Ministers. She demanded that the Army regain control over Poland immediately with no calls for "winter quarters". With over 300,000 soldiers in Eastern Poland, the Czarina did not see why an advance was not possible. Surely, the Germans could not fight on two fronts for long?!!!

With another 400,000 Russian soldiers in various stages of training, the war would at worst be over in the Spring. If not, the Czarina authorized another 500,000 men to be raised in the Spring.

The Czarina would be shocked to discover that French and German Regular forces, volunteers and conscripts were already reaching the millions. For the first time, the Czarina began to realize the sheer scale of the mobilization which would dwarf even the armies of of the Napoleonic Wars.

Still, the Czarina demanded a "Christmas Offensive".

The German and Polish defenses, while not well entrenched, would nevertheless route the Russians which had been ordered forward again and again into the teeth of machine guns, repeating rifles and brutally accurate light artillery. Casualties reached a shocking 50,000 in less than a week and the Russians would withdraw after a flanking movement threatened to cut them off. Only a desperate stand would allow 200,000 Russian soldiers to escape the Salient with the loss of 20,000 prisoners.

The Russians were almost entirely ejected from Poland and were forced back onto Minsk.

The Czarina would summon daily councils to understand the failures of the campaign. Officers holding obsolete military strategy views would be identified and replaced by more modern opinions. Too many of her loyal officers had maintained that nothing had changed from the mid-20th century. But the shift of power towards defensive warfare had proven costly. Soon, the Russians would adapt the doctrines of flanking maneuvers if possible and, if not, most attacks being proceeded by mass bombardments of heavy artillery.

The Bosporus

Of course, the Czarina was not content to just wage war on land. The obvious deficiency of the Baltic Fleet relative to the Americans ensured that the Baltic was, yet again a British lake. However, the Black Sea fleet remained free and fears that the British may attempt to blockade the Bosporus would lead the larger Black Seas Fleet into the Mediterranean to join with the French.

The British Royal Navy had largely blockaded the French along the English Channel and Atlantic ports of France but this had proven impossible to extend through Spain, southern France, etc. Instead, the Royal Navy's Mediterranean fleet would face the same problems as before. Badly outnumbered by the Latin Alliance of France, Spain and Italy, the Royal Navy was forced to defend multiple strongpoints (Gibraltar, Malta and the Suez) while also attempting to shield their Egyptian and Moroccan allies. This prevented the Royal Navy from consolidating their forces into a effective attacking force. The "initiative" would remain with the Latin Alliance.

In December, 8 of the Russian Navy's strongest vessels would sail out into the Mediterranean and rendezvous at Spezia with the bulk of the Italian Fleet and several French vessels.

Once again, the Italian Army would prepare to embark upon transports and follow their navy the short distance to Malta, thus carving the British hegemony in the Mediterranean in half.

Gibraltar

Like Malta, Gibraltar was a British bastion. However, unlike previous wars, the peninsula was no longer protected by an invulnerable Royal Navy. The French arsenal had lent eight heavy 12-inch guns to be emplaced upon the approaches to Gibraltar. The rapid increase in lethality in artillery would put, for the first time, the harbor would be within range of land-based guns. This would effectively prevent the British from being able to safely dock. Ships would only remain in harbor for short periods, always fearful of the scream of shells from the landward side. Soon, the peninsula's usefulness as a base was significantly reduced as guns capable of reaching five miles could cover the entire distance (of three miles) to the far end of the harbor.

Both the port facilities and civilian settlements in Gibraltar were swiftly so severely damaged that the harbor's utility was nearly useless.

Plans for "spoiling attacks" into Spain to sabotage the guns were halted as spotters spied the digging of trenches and arrival of over 12,000 Spanish soldiers. The British garrison dared not sally forth. Instead, they would huddle in the caves carved through the Rock of Gibraltar over the course of centuries. The fact that gun emplacements also prevented an allied assault didn't help morale very much. Once again, Gibraltar was under siege as the British faced being starved out.

The Western Mediterranean squadron of the Royal Navy would be ordered away from Gibraltar as there was nothing they could do to aid the fortress and instead blockade Cadiz where they could be called upon to aid Gibraltar in an emergency.

New Jersey - camp for 1st Brigade, New York Volunteers

General of Volunteers Theodore Roosevelt had been granted a Brigade (three Regiments) and had been given leave to raise officers up to junior Lieutenant. The US Army had been long moving away from allowing high-ranking gentlemen to military command based on social status. This had been necessary in the Civil War but the large number of graduates from West Point over the past decades, US Army policy of being "officer heavy" and other strategy would ensure that most units could be organized by experienced men.

Roosevelt had, of course, served in Africa (for the Co-Protectorate) and in Brazil. Being a Republican Senator also helped. But Roosevelt would NOT be given leave to raise dozens to hundreds of men to officer ranks. Instead, officers were transferred from other units, from the reserve list, from regional militias and directly from West Point. But Roosevelt would be able to "recommend" some junior officer commissions which included his friend Winston Churchill and his kinsmen Tadd Roosevelt and Franklin Roosevelt.

By happenstance, an engineering battalion would be assigned to the 1st Brigade which included Churchill's younger brother, senior Lieutenant Jack Churchill as well.

Also attached to the Regiment would be a battalion of light artillery pieces.

Having resigned from the Senate as he expected war to be broken out at any point, the General wanted to be at the forefront of battle. With 5000 (mostly New Yorkers) good men under arms and with months of training (something volunteers in previous American wars seldom received), Roosevelt was anxious to get off to war. He preferred Cuba as his service in Brazil had been disappointing.

However, Roosevelt would NOT be pleased to learn that his 1st New York Volunteers would be placed under command of a regular officer, Brigadier General John Pershing. Roosevelt considered his experience superior to Pershing but the two would eventually forge a good working relationship over the past few months as Pershing realized that Roosevelt was not a dilatant looking for glory without doing the work.

Though outraged by the Latin Alliance attack on New York, Roosevelt was excited at the prospect of finally being back in battle.

Pershing and Roosevelt would be ordered to Washington to coordinate the formation of a full army of Volunteers and Regulars.

Eastern Poland

Having expected a quick collapse of the Germans, the Czarina would spend much of the fall berating her Ministers. She demanded that the Army regain control over Poland immediately with no calls for "winter quarters". With over 300,000 soldiers in Eastern Poland, the Czarina did not see why an advance was not possible. Surely, the Germans could not fight on two fronts for long?!!!

With another 400,000 Russian soldiers in various stages of training, the war would at worst be over in the Spring. If not, the Czarina authorized another 500,000 men to be raised in the Spring.

The Czarina would be shocked to discover that French and German Regular forces, volunteers and conscripts were already reaching the millions. For the first time, the Czarina began to realize the sheer scale of the mobilization which would dwarf even the armies of of the Napoleonic Wars.

Still, the Czarina demanded a "Christmas Offensive".

The German and Polish defenses, while not well entrenched, would nevertheless route the Russians which had been ordered forward again and again into the teeth of machine guns, repeating rifles and brutally accurate light artillery. Casualties reached a shocking 50,000 in less than a week and the Russians would withdraw after a flanking movement threatened to cut them off. Only a desperate stand would allow 200,000 Russian soldiers to escape the Salient with the loss of 20,000 prisoners.

The Russians were almost entirely ejected from Poland and were forced back onto Minsk.

The Czarina would summon daily councils to understand the failures of the campaign. Officers holding obsolete military strategy views would be identified and replaced by more modern opinions. Too many of her loyal officers had maintained that nothing had changed from the mid-20th century. But the shift of power towards defensive warfare had proven costly. Soon, the Russians would adapt the doctrines of flanking maneuvers if possible and, if not, most attacks being proceeded by mass bombardments of heavy artillery.

The Bosporus

Of course, the Czarina was not content to just wage war on land. The obvious deficiency of the Baltic Fleet relative to the Americans ensured that the Baltic was, yet again a British lake. However, the Black Sea fleet remained free and fears that the British may attempt to blockade the Bosporus would lead the larger Black Seas Fleet into the Mediterranean to join with the French.

The British Royal Navy had largely blockaded the French along the English Channel and Atlantic ports of France but this had proven impossible to extend through Spain, southern France, etc. Instead, the Royal Navy's Mediterranean fleet would face the same problems as before. Badly outnumbered by the Latin Alliance of France, Spain and Italy, the Royal Navy was forced to defend multiple strongpoints (Gibraltar, Malta and the Suez) while also attempting to shield their Egyptian and Moroccan allies. This prevented the Royal Navy from consolidating their forces into a effective attacking force. The "initiative" would remain with the Latin Alliance.

In December, 8 of the Russian Navy's strongest vessels would sail out into the Mediterranean and rendezvous at Spezia with the bulk of the Italian Fleet and several French vessels.

Once again, the Italian Army would prepare to embark upon transports and follow their navy the short distance to Malta, thus carving the British hegemony in the Mediterranean in half.

Gibraltar

Like Malta, Gibraltar was a British bastion. However, unlike previous wars, the peninsula was no longer protected by an invulnerable Royal Navy. The French arsenal had lent eight heavy 12-inch guns to be emplaced upon the approaches to Gibraltar. The rapid increase in lethality in artillery would put, for the first time, the harbor would be within range of land-based guns. This would effectively prevent the British from being able to safely dock. Ships would only remain in harbor for short periods, always fearful of the scream of shells from the landward side. Soon, the peninsula's usefulness as a base was significantly reduced as guns capable of reaching five miles could cover the entire distance (of three miles) to the far end of the harbor.

Both the port facilities and civilian settlements in Gibraltar were swiftly so severely damaged that the harbor's utility was nearly useless.

Plans for "spoiling attacks" into Spain to sabotage the guns were halted as spotters spied the digging of trenches and arrival of over 12,000 Spanish soldiers. The British garrison dared not sally forth. Instead, they would huddle in the caves carved through the Rock of Gibraltar over the course of centuries. The fact that gun emplacements also prevented an allied assault didn't help morale very much. Once again, Gibraltar was under siege as the British faced being starved out.

The Western Mediterranean squadron of the Royal Navy would be ordered away from Gibraltar as there was nothing they could do to aid the fortress and instead blockade Cadiz where they could be called upon to aid Gibraltar in an emergency.

Chapter 322

January, 1906

Washington

Senator Henry M. Teller of Colorado would spend weeks demanding that the United States Government publicly state that any invasion of Cuba would be to "support independence" and not to annex the island (this would extend to Puerto Rico and Hispaniola as well) in the "Teller Amendment" to the appropriations bill for the war.

A western "Silverite" Republican, Teller nearly left the party when the nation went back on the Gold Standard. However, he remained after much convincing and would become among the strongest anti-Imperialists in Congress.

Santiago

Admiral Wainwright had been proud of the US Navy's performance in New York but the fact remained that the Atlantic Squadron had been decimated. Three of the ten heavy ships had been lost (the Arizona, Maine and Mescalero) while the old Louisiana-class Virginia and Massachusetts were severely damaged. Now in Boston, the ships may be months away from returning to service. Indeed, this had been a week-long argument within the Naval Office as to whether or not it would even be worth it to repair the old ships. Some of the Admiralty had been certain that using resources to repair twenty-year-old vessels was a waste. However, Wainwright would point out that not repairing these ships would do nothing to speed up the construction of the newer classes.

Even the Michigan and the Montana had taken hits and required repair. More ominously the Michigan continued to have engine difficulties. The last thing the Navy needed was yet another class of ships with endemic design flaws (the Iowa-class came to mind). With the South Carolina expected to be launched in March with a month or two of shakedown after that, the Atlantic fleet would be greatly augmented.

But Wainwright would take a great chance and dispatch the USS Florida and the USS Michigan to the Caribbean squadron in January, 1906 as the American land forces would gather along the southern ports. In Pensacola, Mobile and New Orleans, tens of thousands American soldiers were gathering. The Army had at least predicted that America may someday fight in Cuba to aid the rebels and a plan had been in place by the General Staff (largely copied from the old Prussian mold which was the template for virtually all major European armies by 1906).

In late January, the USS Michigan and USS Montana as well as the more modern ships of the Caribbean squadron - the USS Oregon, USS Santee, USS Wisconsin and USS Ohio - would and lead an assault on Santiago harbor, home to the Spanish West Indies Squadron. However, the four cruisers and two destroyers present were considered old and obsolete even by Spanish standards. The newest vessel was 11 years old (a long time given the development of naval technology) and none of the vessels came close to matching the American guns or arbor. The Spanish guns were notoriously prone to failure, the hulls had been fouled and many of the engines were years overdue for refurbishment.

In short, the ensuing engagement was not some much a battle as a slaughter. Entering Santiago Harbor, the American vessels obliterated the Spanish ships, none escaping. Only the Montana and Wisconsin suffered any sort of blows....neither serious.

However, the Michigan would, once again, endure engine trouble and would be escorted by the USS Florida to the Norfolk shipyards where here sister ship was nearing completion.

In the meantime, the remainder of the American West Indian Squadron, augmented by several older model ships, would prepare a two-pronged invasion. No longer fearing any interference at sea, the Americans would first land along the southeast coast near Guantanamo Bay (east of Santiago de Cuba) while a second invasion would occur in Matanzas (east of Havana). The plan would be to cut off the two major cities from the rest of the country and allow the insurgents in the countryside to flock to the American colors.

Washington

Senator Henry M. Teller of Colorado would spend weeks demanding that the United States Government publicly state that any invasion of Cuba would be to "support independence" and not to annex the island (this would extend to Puerto Rico and Hispaniola as well) in the "Teller Amendment" to the appropriations bill for the war.

A western "Silverite" Republican, Teller nearly left the party when the nation went back on the Gold Standard. However, he remained after much convincing and would become among the strongest anti-Imperialists in Congress.

Santiago

Admiral Wainwright had been proud of the US Navy's performance in New York but the fact remained that the Atlantic Squadron had been decimated. Three of the ten heavy ships had been lost (the Arizona, Maine and Mescalero) while the old Louisiana-class Virginia and Massachusetts were severely damaged. Now in Boston, the ships may be months away from returning to service. Indeed, this had been a week-long argument within the Naval Office as to whether or not it would even be worth it to repair the old ships. Some of the Admiralty had been certain that using resources to repair twenty-year-old vessels was a waste. However, Wainwright would point out that not repairing these ships would do nothing to speed up the construction of the newer classes.

Even the Michigan and the Montana had taken hits and required repair. More ominously the Michigan continued to have engine difficulties. The last thing the Navy needed was yet another class of ships with endemic design flaws (the Iowa-class came to mind). With the South Carolina expected to be launched in March with a month or two of shakedown after that, the Atlantic fleet would be greatly augmented.

But Wainwright would take a great chance and dispatch the USS Florida and the USS Michigan to the Caribbean squadron in January, 1906 as the American land forces would gather along the southern ports. In Pensacola, Mobile and New Orleans, tens of thousands American soldiers were gathering. The Army had at least predicted that America may someday fight in Cuba to aid the rebels and a plan had been in place by the General Staff (largely copied from the old Prussian mold which was the template for virtually all major European armies by 1906).

In late January, the USS Michigan and USS Montana as well as the more modern ships of the Caribbean squadron - the USS Oregon, USS Santee, USS Wisconsin and USS Ohio - would and lead an assault on Santiago harbor, home to the Spanish West Indies Squadron. However, the four cruisers and two destroyers present were considered old and obsolete even by Spanish standards. The newest vessel was 11 years old (a long time given the development of naval technology) and none of the vessels came close to matching the American guns or arbor. The Spanish guns were notoriously prone to failure, the hulls had been fouled and many of the engines were years overdue for refurbishment.

In short, the ensuing engagement was not some much a battle as a slaughter. Entering Santiago Harbor, the American vessels obliterated the Spanish ships, none escaping. Only the Montana and Wisconsin suffered any sort of blows....neither serious.

However, the Michigan would, once again, endure engine trouble and would be escorted by the USS Florida to the Norfolk shipyards where here sister ship was nearing completion.

In the meantime, the remainder of the American West Indian Squadron, augmented by several older model ships, would prepare a two-pronged invasion. No longer fearing any interference at sea, the Americans would first land along the southeast coast near Guantanamo Bay (east of Santiago de Cuba) while a second invasion would occur in Matanzas (east of Havana). The plan would be to cut off the two major cities from the rest of the country and allow the insurgents in the countryside to flock to the American colors.

The reason why during the Spanish American war the US Army had to rely on calling up a bunch of ancient Civil War veterans is that they didn’t have any experienced generals who were younger. in this world US has waged war several times so they don’t need to call up the elderly to led the armiesshouldn't there be civil war veterans still in service ? In OTL some of them asked Willson to serve in ww1 but he said no here with the war being way earlier how is Scott in command instead of one of them?

Also , this version of the Spanish American War is 7 years later than in OTL. Even the youngest vets would be in their late 60’s.The reason why during the Spanish American war the US Army had to rely on calling up a bunch of ancient Civil War veterans is that they didn’t have any experienced generals who were younger. in this world US has waged war several times so they don’t need to call up the elderly to led the armies

Chapter 323

February, 1906

Guantanamo Bay

Having alighted upon Cuban soil, the 1st New York Volunteers would serve alongside a hastily cobbled together 2nd Army group under General Pershing. The 1st New York Brigade bore roughly 5000 men to the 5th Brigade was composed of eight regiments of regulars. These included two Colored Troops of Cavalry, among the last non-integrated units in the Army (since 1899, all new Regular Army regiments were integrated). However, the American cavalry troops remained disproportionately Colored and no one wanted to tear apart functional units prior to a war. The 1st New York was also integrated.

Pershing was in overall command of what was deemed the 1st Expeditionary Group (the 2nd Expeditionary Group was landing east of Havana) while direct control over the 5th Brigade came to Colonel Allyn Capron (his son Captain Allyn Capron was serving in the 1st Expeditionary Group).

Having risen from the ranks himself instead of graduating from West Point, Capron did not hold the same amused contempt Roosevelt often felt from regular army officers.

After three days of organizing supplies and dispatching scouts, the Americans would march east towards Santiago in a burst of confidence. After all, the Spanish had done next to nothing to stop them.

Until they did.

Only at the last minute did the Cavalry alert the overall army of the impending ambush and Capron was able to withdraw quickly as the first shells started coming down and the Spanish flanking movement threatened to envelope the Americans of the 5th Brigade.

Pershing promptly ordered up the 1st New York Brigade and prepared for what he thought would be a modest skirmish. However, the 5000 men entrenched upon San Juan Hill and the nearby hills would be less than enthused about giving up an inch of ground. By 1906, the Spanish had at least upgraded their rifles with modern models and took a terrible toll upon the Americans. Only the arrival of flanking forces with machines guns enfilading the Spanish would force the defenders to fall back towards Santiago. The Americans declared victory but, in all reality, had suffered twice the casualties to take this hill. Nearly a tenth of Pershing's force had been killed or wounded.

Roosevelt was, naturally, ecstatic despite the losses. It felt so good to be at war again.

Macapa

Brigadier Henry Lawton would consolidate his forces in Macapa. On the whole, the 4000 troops he'd been assigned to protect the Amazon River had been fairly well trained. However, the loss of half this number inland would leave the Brigadier severely shorthanded.

The Brazilians were obviously intent on retaking the Northern Amazon and rumor had it over 6000 soldiers had been station nearby at the Brazilian city of Belem.

Guantanamo Bay

Having alighted upon Cuban soil, the 1st New York Volunteers would serve alongside a hastily cobbled together 2nd Army group under General Pershing. The 1st New York Brigade bore roughly 5000 men to the 5th Brigade was composed of eight regiments of regulars. These included two Colored Troops of Cavalry, among the last non-integrated units in the Army (since 1899, all new Regular Army regiments were integrated). However, the American cavalry troops remained disproportionately Colored and no one wanted to tear apart functional units prior to a war. The 1st New York was also integrated.

Pershing was in overall command of what was deemed the 1st Expeditionary Group (the 2nd Expeditionary Group was landing east of Havana) while direct control over the 5th Brigade came to Colonel Allyn Capron (his son Captain Allyn Capron was serving in the 1st Expeditionary Group).

Having risen from the ranks himself instead of graduating from West Point, Capron did not hold the same amused contempt Roosevelt often felt from regular army officers.

After three days of organizing supplies and dispatching scouts, the Americans would march east towards Santiago in a burst of confidence. After all, the Spanish had done next to nothing to stop them.

Until they did.

Only at the last minute did the Cavalry alert the overall army of the impending ambush and Capron was able to withdraw quickly as the first shells started coming down and the Spanish flanking movement threatened to envelope the Americans of the 5th Brigade.

Pershing promptly ordered up the 1st New York Brigade and prepared for what he thought would be a modest skirmish. However, the 5000 men entrenched upon San Juan Hill and the nearby hills would be less than enthused about giving up an inch of ground. By 1906, the Spanish had at least upgraded their rifles with modern models and took a terrible toll upon the Americans. Only the arrival of flanking forces with machines guns enfilading the Spanish would force the defenders to fall back towards Santiago. The Americans declared victory but, in all reality, had suffered twice the casualties to take this hill. Nearly a tenth of Pershing's force had been killed or wounded.

Roosevelt was, naturally, ecstatic despite the losses. It felt so good to be at war again.

Macapa

Brigadier Henry Lawton would consolidate his forces in Macapa. On the whole, the 4000 troops he'd been assigned to protect the Amazon River had been fairly well trained. However, the loss of half this number inland would leave the Brigadier severely shorthanded.

The Brazilians were obviously intent on retaking the Northern Amazon and rumor had it over 6000 soldiers had been station nearby at the Brazilian city of Belem.

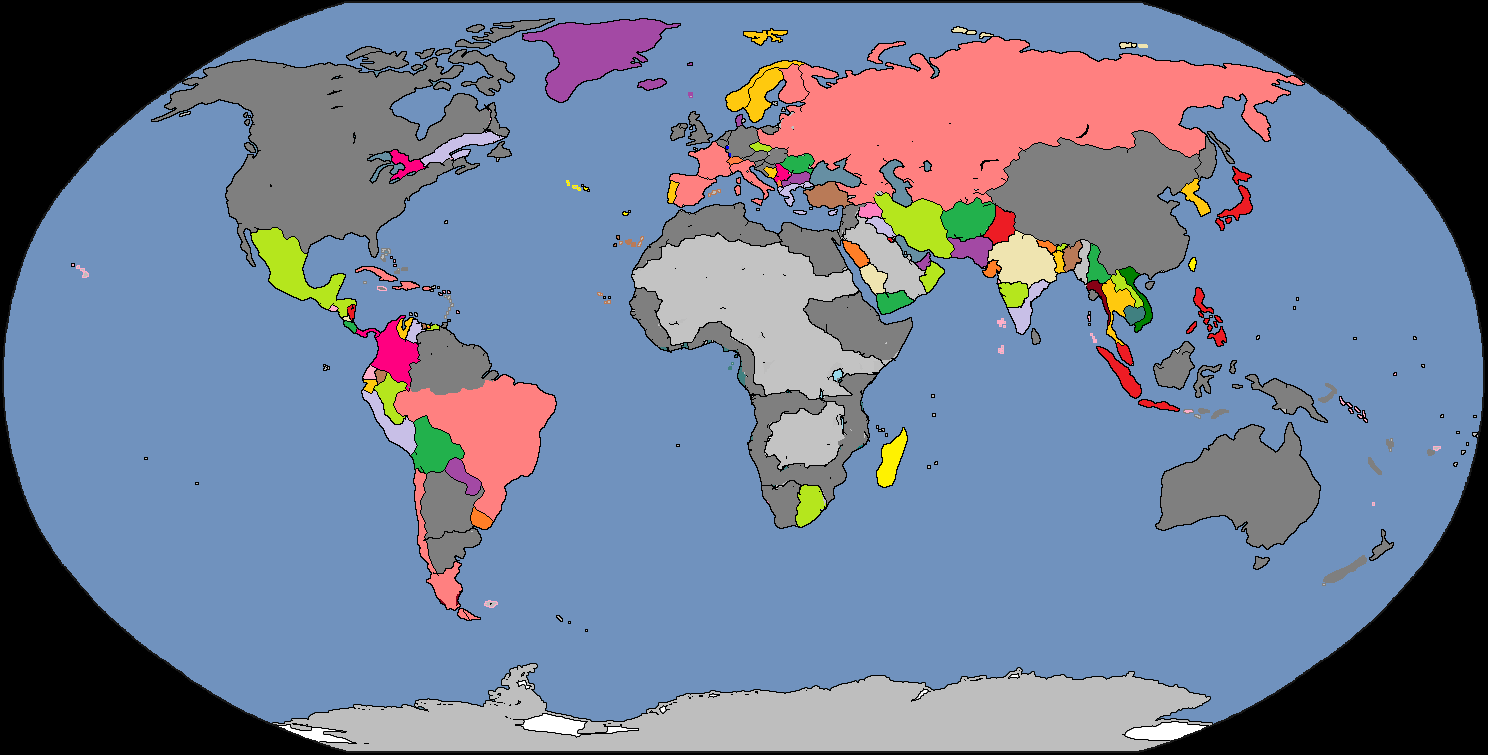

Map of World - 1906

General alliances of 1906

Latin Alliance, Russia, Brazil, Chile - Peach colored

Britain, Germany, America, Hungary, Croatia, Belgium, Netherlands, Argentine, Buenos Aires, Morocco, Egypt, Ethiopia, China - Colored in Grey

Latin Alliance, Russia, Brazil, Chile - Peach colored

Britain, Germany, America, Hungary, Croatia, Belgium, Netherlands, Argentine, Buenos Aires, Morocco, Egypt, Ethiopia, China - Colored in Grey

Wut? Switzerland is in the Latin alliance? What is this meant to be? When did they stop being neutral?

It is neutral. It is marked in orange, not peach.

Maybe the nuance of orange is very close to the peach one , but at first glance, that's how it looks, one and same colourIt is neutral. It is marked in orange, not peach.

Share: