that much is obvious!From the title itself: resurgent

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Russia Resurgent: REDUX

- Thread starter Sarthak

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

i guess that's possible, but the early kazakh government in and of itself were very competent and not likely to fall for the belarusian and crimean trapsNazarbayev dies?

writer's block is a drag at times I have to admit.....I liked a lot the first version, but this look nice too. But all of your TLs are good, it's a pity for you to have discarded some of them.

*some* privatization of the sector is inevitable at this point, but yes it is imperative to keep the majority under the public sectorNo privatisation of oil and gas infrastructure!

The new PODs are creative and clever. Hopefully in this way Russia could be like a phoenix, rising from the ruins of USSR.

thanks! hope you guys enjoy!Looks good

Very possible that an alt union state happens between Ukraine and russia ittl instead of russia and belarus.Good to hear from you again Sārthākā; I really like this new instalment. So at least for the moment being, I think that Russia will become a giant Belarus (almost all crucial sectors state-owned and with only limited privatization) and that then a more liberal figure will be elected and start to privatize things (maybe Yavlinsky?). Maybe Leonid Kuchma (if he still raises to power) will become TTL version of Lukashenko and form a union state between Russia and Ukraine in the early 2000s?

Hope to hear from you soon!

Also this announcement may excite @Kienle and @Marco Rivignani, but after studying Italian and Vietnamese politics a whole lot more to gain proper understanding, Italian and Vietnamese politics will be taking a lot of divergent turns ittl. I hope I can make the two countries more interesting than the older version!

Sounds really interesting! We'll see what happens......Also this announcement may excite @Kienle and @Marco Rivignani, but after studying Italian and Vietnamese politics a whole lot more to gain proper understanding, Italian and Vietnamese politics will be taking a lot of divergent turns ittl. I hope I can make the two countries more interesting than the older version!

Looking forward to see it!Also this announcement may excite @Kienle and @Marco Rivignani, but after studying Italian and Vietnamese politics a whole lot more to gain proper understanding, Italian and Vietnamese politics will be taking a lot of divergent turns ittl. I hope I can make the two countries more interesting than the older version!

As a Vietnamese I can hardly understand how you would make Vietnamese politics more interesting, unless you make the Communist government fallAlso this announcement may excite @Kienle and @Marco Rivignani, but after studying Italian and Vietnamese politics a whole lot more to gain proper understanding, Italian and Vietnamese politics will be taking a lot of divergent turns ittl. I hope I can make the two countries more interesting than the older version!

With Italy there's a lot of potential with changing mani pulite or the fallout from mani pulite, but with Vietnam at best you'd just have more reformists like Võ Văn Kiệt or if you want to be funny have hardliners like Lê Đức Anh seize more power. But it's all just Communists, man

Last edited:

That said, how's the start?

It looks interesting. The chapter was well written and I love the amount of detail you put in. Incredibly detailed TLs like WMIT and Kentucky Fried Politics are always fun to read IMO.

Chapter 2: The Immediate Aftermath

Chapter 2: The Immediate Aftermath

***

Chapter 17 of Russian Political History by Cambridge University

On November 8, immediately after the Minsk protocols, President Alexander Rutskoy of the new Russian Union had to form a new government for the newly independent nation if he wanted to survive the inevitable economic and social rupture that would come from the end of the Soviet Union. He decided to form a national unity government composed of politicians from all spectrums of society in a bid to make sure that the country would be able to soften their fall from grace and power.

Grigory Yavlinsky.

As Ivan Silaev resigned as the last Soviet Prime Minister, the issue of the premiership within Russia reared its head. Rutskoy knew that the appointment of the prime minister would play an important role in the economic recovery of the nation decided to call upon someone unorthodox to become the Prime Minister of the Russian Union. Grigory Yavlinsky was in Lviv packing his bags and personal items to move back to Russia as per his Russian citizenship when he received a phone call that evening from Rutskoy himself. Yavlinsky remembers the astonishment in his memoirs completely and vividly. “I was packing my bags, looking after my land tenants, and moving the family when the phone rang. I picked it up, and was surprised to hear the gruff voice of President Rutskoy. He offered me in no certain terms the premiership of Russia. It obviously pained him to ask me, however the desperation of the new unenviable economic position had forced him to turn to me it seemed. I had no other choice. I had to accept.”

Yavlinsky had under the Gorbachev and Yeltsin been an extremely important political figure, both as Department Head of the State Commission for Economic Reforms and as the government’s official economic advisor. He certainly had the reputation and experience for a premiership, and Rutskoy was obviously putting the need of the economy and the government first when he appointed Yavlinsky as Prime Minister of Russia despite his personal distaste of the economist. With the issue of the Prime Minister quickly resolved, on November 9, President Rutskoy submitted a list of potential candidate members for the cabinet to Anatoly Sobchack, the Vice President and Yavlinsky, the newly minted Prime Minister who was on his way back to Moscow via airplane. Most of the candidates were approved by the Vice President and Prime Minister for the National Unity Government, however Yavlinsky replaced Anatoly Chubais as the candidate for the Ministry of Economics and replaced him with Petr Aven, an old economic associate of Yavlinsky. With these measures taken into account, on November 10, Rutskoy formed a new governmental cabinet called the Yavlinsky I consisting of the following peoples:-

Money supply through fraud also increased by 34% in the country and Russian money supply from overall means of supply grew by 18 times throughout the country. Inflation also ran rampant throughout the country, with average prices in the country already hiking all the way to 245% already. It was becoming clear to the new government that immediate economic measures would need to take place unless the government wanted to have an economic depression on their hands. A sharp decline in economic value had been anticipated by many after the fall of the Soviet Union, but the government would do anything to soften the economic blows.

A flee market in Rostov.

The three main economic actors of the new government were to be Prime Minister Grigory Yavlinsky, Minister for Foreign Economic Relations Anatoly Chubais and Minister of Economics and Finance Petr Aven. Both Aven and Yavlinsly were advocates of a Swedish and Finnish style social democracy and both of them outvoted Chubais regarding the issue of a shock therapy, which Yavlinsky and Aven both found to be unsuitable and irresponsible within the economic context of the newly independent Russian Union. Chubais himself had in 1989 been an advocate of social democratic economics within the Soviet Union before he had changed his tune, and as such it wasn’t hard for the other two economists to change the mind of the man. In coordination with the other members of the cabinet, both Yavlinsky and Aven decided to compile economic statistics to deem the best economic reform needed for the Russian state, and at the same time, Chubais was dispatched to America to the headquarters of the International Monetary Fund to secure a loan which would be used as a stimulus package by the Russian government.

Petr Aven.

On November 15, after five days of intensive economic data collection from throughout the country, Yavlinsky and Aven decided that a mixed economic model based on gradual privatization and social democratic models would be the best suited one for the Russian economy. Yavlinsky amended the 500 Days Program that he had earlier advocated, and amended the program to become a 750 days program. The 750 Days Program which was written down on November 15 and presented to the cabinet on November 20, 1991 was a complete break from existing views, academic concepts, and journalistic economic publications at the time with respect to the interpretation of society’s economic problems. It was the first real attempt in economics to circulate a new radical change in ethical assessment of social and economic phenomena. It was a complete program that predicted the main lines of dissolution in society and correctly pinpointed the crux of possible conflicts on the event of implementation of radical economic reforms such as labor conflicts and wage conflicts, breakdown of the welfare system and regional hurdles of economic development. As such it recommended the following measures to make sure that the economic damage to the country was dampened:-

The cabinet approved of the economic plan put forward by the two economists and on November 24, the plan was given to the Russian Soviet of the Republic. The Soviet of the Republic which was a precursor to the Russian State Duma, passed the 750 Days Program with a total of 80 in favor of the plan, 36 in opposition to the program and around 10 deputies abstaining from voting during the deliberations. On November 26, it was declared official policy of the Russian government in regards to the economy.

On November 29, the Russian government successfully managed to gain a $4.2 billion stimulus package from the International Monetary Fund, and negotiations to enter the IMF began between Moscow and Washington. The stimulus package was used to increase the economic stability of the ruble, as had been advised by Aven and Yavlinsky.

***

Chapter 11 of Post-Soviet Drama: The Pandemonium of Nations

The independence of the Soviet republics created an immediate problem throughout the former union. The question of the armed forces, the Security Council seat, the navy and most importantly the question of nuclear weapons. On November 18, the Ukrainian government contacted the Russian government and asked for moderation from the United States whilst managing the matters of the Security Council, and the nuclear weapons of the former Soviet Union. Leonid Kravchuk, the new President of the Republic of Ukraine asked Rutskoy for a meeting in one of the western countries alongside Kazakhstan to end the nuclear question of the former Soviet Union once and for all. Nuclear dissemination had been one of the top policies made by Rutskoy’s government, and Rutskoy agreed to the invitation.

On November 29, Leonid Kravchuk called the Russian government once again and told the Russians “I have spoken with the American government led by President Bush, and he has told me that with deliberation with the other members of NATO, the country of Portugal has agreed to hold a conference for the Ukraine, Russia and Kazakhstan in regards to the nuclear weapons that are residing within our soils. The British, French and Chinese governments have agreed to send delegations to confirm the legal successor of the Soviet Union in the United Nations Security Council. The conference will take place in Lisbon on December 26 and last until December 29.”

Rutskoy gave power to Sobchak temporarily as his vice president as he left the country to meet with the delegations that would be sent to Lisbon to sign and negotiate a treaty regarding the armed forces of the Soviet Union. The signing of the protocol was taken place during the ongoing process of reorganization of the former Soviet Union into the Commonwealth of the Independent States and the creation of a monetary union between the members of the CIS.

Flag of the CIS - Commonwealth of Independent States

In Lisbon, Rutskoy met with Kravchuk and Nazarbayev, as the leaders of the three post-Soviet states which held nuclear weapons within their borders. The Americans had sent James Baker, the US Secretary of State as their delegation to the meeting. On the other hand, the Britain had sent Douglas Hurd, the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, and the French had sent Rouland Dumas, the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, and the Chinese had sent Tang Jiaxuan, the Chinese Foreign Minister of the People’s Republic respectively as their delegates for the meeting. Rutskoy was accompanied by the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Andrei Kozyrev.

The Russian government’s position was clear. It was the legal successor of the Soviet Union, and as the Russians had already taken up the post of the Soviet ambassador in the United Nations, the USSR’s seat in the Security Council, and the nuclear weapons would have to be given to Russia. The nuclear weapons in Kazakhstan and Ukraine were useless for any military action due to their launch codes being in Moscow, however the possibility of independent research into nuclear weapons was a topic that both powers of the USA and Russia wanted to avoid within the borders of Ukraine and Kazakhstan.

James Baker.

The Kazakh and Ukrainian governments wished to have some kind of power over Moscow in the era of independence, and at first both Kravchuk and Nazarbayev refused to hand over the nuclear weapons to Russia, whilst they agreed to recognize Russia as the legal successor to the Soviet Union, and as such take the Security Council seat. Baker would later write in his memoirs, “The tension was fractious. Rutskoy was obviously still angry at the breakup of the union, and the Kazakhs and Ukrainians believed that they held some sway over the Russian government due to their nuclear weapons. However in that situation, Mr. Hurd and Mr. Dumas clearly understood that Russia held the cards. In the situation of a last resort, the Russians could activate the launch codes of the nuclear weapons situated on Ukrainian and Kazakh soil, and detonate them, bringing a rain of destruction down on the newly independent states. Mr. Kozyrev, the Russian Foreign Minister would slap the reality of the situation onto President Kravchuk and President Nazarbayev when he pointed out the reality of the situation. He was a bit crude in the manner that he conveyed the meaning, however it got the point across.”

Relations between the new independent states were already cold, as the conflicting personalities of the new leaders clashed against one another and the subtle threat of Russia irredentist claims in Ukrainian Donetsk and Luhansk, and in Kazakhstan, which was at the time Slavic majority was not spoken aloud, however it was understood by everyone present. The Kazakhs and Ukrainians would not be able to use the nuclear weapons they possessed to any meaningful amount if the Russians invaded, and the loyalty of the Ukrainian Armed Forces and the Kazakh Armed Forces, consisting of many ethnic Russians was also largely suspect in such a scenario. Kravchuk caved first, and agreed to return the nuclear weapons if he got a concession out of Russia regarding Ukrainian sovereignty. He demanded a perpetual Russian guarantee of Ukrainian territorial, diplomatic and political sovereignty. Rutskoy agreed to give this concession whilst the Kazakhs demanded the same. Rutskoy agreed to extend the offer to the Kazakhs as well.

On December 28, 1991 the Lisbon Protocol was typed down by the parties present and laid down the following major points:-

***

Chapter 16 of The Question of Transnistria and Gagauzia.

Before the Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, and the creation of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1940, Bessarabia had been a part of Romania after World War I and a part of the Russian Empire before that. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany which led to the Soviet annexation of Moldova was declared null and void by the Moldovan Supreme Soviet and they declared independence on the 27th of August 1991 like so many of the other republics within the Soviet Union. Before the creation of the Moldavian SSR, the territory that made up Transnistria was a part of Ukraine and only added to Moldova in 1940.

During the last years of the 1980s, Gorbachev’s Perestroika and Glasnost allowed political pluralism at the regional level. In the Moldovan SSR, the nationalist movement became the leading political force as a result. As these movements exhibited increasingly nationalist sentiments and expressed an intent to leave the USSR and uniting with Romania, these movements encountered growing levels of opposition from the primarily Russian and Ukrainian ethnic minorities living in the Moldovan SSR. The opposition was extremely strong within the boundaries of Transnistria, where the ethnic Moldovan population was outnumbered by the general Slavic population, largely due to the history of Russian and Ukrainian settlement in the region, with links going as far back as the Russian Empire and continued under the Soviet Union.

On 31 August 1989, the Supreme Soviet of the Moldavian SSR enacted two laws. One of them made Moldovan the official language, in lieu of Russian, the de facto official language of the Soviet Union. It also mentioned a linguistic Moldo-Romanian identity. The second law stipulated the return to the Latin Romanian alphabet instead of the soviet introduced Cyrillic script. Moldovan language was the term used in the former Soviet Union for a virtually identical dialect of the Romanian language during 1940–1989. On 27 April 1990, the Supreme Soviet of the Moldavian SSR adopted the traditional tricolour (blue, yellow and red) flag with the Moldavian coat of arms and later changed in 1991 the national anthem to Deșteaptă-te, române!, the national anthem of Romania since 1990. Later in 1990, the words Soviet and Socialist were dropped and the name of the country was changed to "Republic of Moldova".

The flag of Transnistria.

These events, coupled with the opening of the Moldovan-Romanian border led many in Transnistria to believe that political union between Moldova and Romania was inevitable. This possibility created ethnic fears in the Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian and Bulgarian community in Transnistria that they would be excluded from most aspects of public life as had been the case in the Baltic countries where their ethnic Russian and Slavic populations were becoming increasingly sidelined. From September 1989, strong scenes of protest broke out all across the Moldovan Republic, but mostly in Transnistria, against the central government’s ethno-centrist policies. These protests soon developed into the formation of secessionist movements in Gagauzia and Transnistria, both of whom had initially sought to remain as autonomous regions in Moldova, however the nationalist dominated Moldovan Supreme Soviet outlawed the initiatives presented by the Transnistrians and Gagauzians. After this, the Gagauz Republic and the Republic of Transnistria declared their independence from Moldova and announced their intention to be reattached to the Soviet Union as independent federal republics.

In the aftermath of the 1991 August Coup in the Soviet Union, the Moldovans achieved full independence, and in Tiraspol, the Transnistrian government decided to conduct a full independence referendum. On November 6, Igor Smirnov, the leader of the Transnistrian independence movement, declared that an independence referendum would be held by the Transnistrian government on the 6th of December, 1991. He also mandated a legislation that made it necessary for all able voters to attend the referendum if they were in the (unrecognized) country.

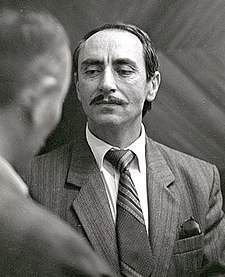

Igor Smirnov of Transnistria.

Smirnov sent invitations to the Ukrainian, Russian, Romanian, Hungarian, American, British and French governments to send supervisors to the referendum to make the referendum result’s legitimate, as he was sure that the secessionists would win. The Russians and Ukrainians agreed to send delegations to the referendum as supervisors, whilst the rest declined, as the western powers and the newly independent Romanian and Hungarian governments did not wish to alienate the Moldovan government, with whom they were trying to cultivate good relations with. President Rutskoy himself was a supporter of Transnistrian and Gagauz independence, and asked the Russian Supreme Soviet to write a legislation in favor of the two gaining full sovereignty. The Ukrainians and Leonid Kravchuk also tacitly supported the two secessionist movements.

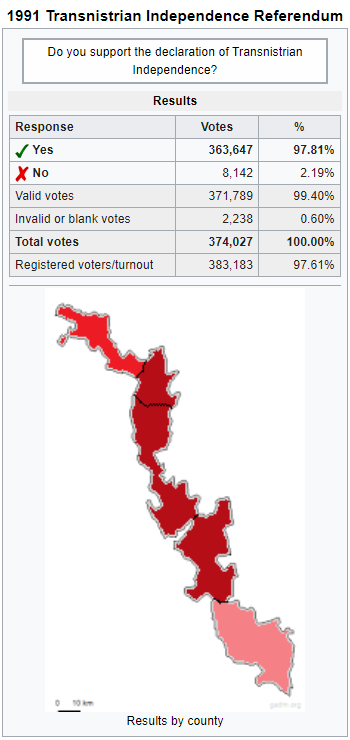

On December 6 the referendum took place, and around 97.81% of all correspondents voted in favor of independence. Even much of the ethnic Moldovan populace of Transnistria voted in favor of independence. Alexander Cooper, a British reporter who worked for the BBC in Moldova during this time remembers, “The Moldovans in the region were perhaps just as fanatic about independence. The Moldovans of the region may have spoken Romanian-Moldovan, however they had lived in an ethnically diverse region, and many were related to the Russians and Ukrainians of the region who would be adversely affected by political union with Romania. As a result, familial loyalty played a large role in making even the ethnic Moldovans vote in favor of independence. There is no doubt that the referendum was rigged by Smirnov, however even a free and fair referendum would have ended in favor of independence. Of that there is no doubt either.”

In the Gagauz Republic, their new President, Stepan Topal was insistent that he would use democratic means of gaining independence, and stated that a referendum would be held on January 17, 1992, and asked the United Nations to intervene and send representatives to supervise the referendum whilst he sent invitations to all of the Commonwealth of Independent States as well. Topal would not receive UN representatives, however Russian and Romanian meddling in Moldova would ensure that he held the referendum in the end, regardless of the lack of representatives of the international organizations.

***

Chapter 6 of The Battle for Dominance in Post-Soviet Caucasus.

In 1991, Chechnya declared its independence from Russia on a unilateral basis. This immediately provoked Russian response, as was expected. Chechnya is situated in the northeast region of the Caucasus. To the east, north, and west, the republic borders with the Russian regions of Dagestan, Stavropol’ krai, Ingushetia, and North Ossetia; to the south, it borders with Georgia. Its territory encompasses 15,678 km. About one-third of the territory is in the plains north of the Terek River, which crosses Chechnya west to east. The southern part of Chechnya, covering another one-third of the total territory, is mountainous—the highest mountains are over 4,000 m high—and poorly accessible. The capital, Grozny, was founded in 1812 as a military outpost of Russian colonialism in the North Caucasus and aptly named “the threatening.” It and the other larger settlements—Gudermes, Shali, and Urus-Martan—all lie in the middle part of Chechnya, between the mountains in the south and the Terek Plains in the north. Most of the intensive fighting took place here; rebels used the mountains in the south as their safe retreat and as a lifeline for military supplies. A large part of the military supplies was brought over mountain paths from Georgia, Dagestan, and Ingushetia.

The available demographic data for prewar Chechnya are not very precise. The reason for this is that, until 1991, Chechnya, together with the much smaller Ingushetia, constituted the Chechen-Ingushetian ASSR. All data from the Soviet Census of 1989 thus relate to the Chechen-Ingushetian ASSR. Extrapolating from the data in the Soviet Census, it can be estimated that, in 1991, the population of Chechnya proper was around 836,000, of which about 700,000 were ethnic Chechens and the rest were predominantly ethnic Russians.

Despite the particularly ferocious attempts at Sovietization, Chechen society, perhaps more than other Caucasian societies, has proved itself to be particularly resistant. In key areas, such as law and justice, loyalty and solidarity, and religion and identity, traditional forms of local organization were preserved. Older Chechens relate that, after the Stalin era, no Chechen was ever brought before a Soviet court of law charged with a serious crime. Instead, the law was administered according to the traditional legal canon, the adat, and enforced by the clans. Such tales may be exaggerated, but they highlight the extent to which traditional ideas about law, as well as traditional procedures for its enforcement, were preserved during Soviet times. Islam, the source of much of customary law called adat, also resisted Soviet atheist campaigns. Adherence to Islam remained an important part of Chechen cultural identity, even if the open practising of religion was not possible in the Soviet Union. The considerable resistance of Chechen society toward Soviet institutions and Soviet culture brought about the parallel existence of two normative systems. This strange juxtaposition of contrasting, often mutually exclusive, norms and procedures, present in all Soviet societies, was particularly prominent in Chechnya. The fact that, to a large extent, the Chechens were sidelined in terms of opportunities in the Soviet Union, made the system even more entrenched. In the Soviet Union, it was difficult to have a career as a Chechen. Even within their “own” republic, key political and economic positions were by and large beyond the reach of Chechens. This was in contrast to other ethnic republics, in which representatives of the titular nation had good career chances up to a certain point. For this reason, the emergence of a Chechen-Soviet elite took place very slowly. Thus, after 1991, a class of decision-makers, who were able to stabilize the political situation and ensure a relatively conflict-free transition in many Union republics and autonomous territories, was lacking in Chechnya.

Dhzokar Dudayev.

In November 1990, an All-National Congress of the Chechen People was convened in Grozny. There, 1,000 delegates, each representing 1,000 Chechens living in the Soviet Union, met to debate the cultural and national concerns of the Chechen people, its future, and its past. This was an unprecedented event, made possible by the spirit of glasnost and perestroika that had led to national mobilization throughout most capitals and most borderlands of the Soviet empire. Among the congress’ many guests of honor was one Dzokhar Dudayev, at the time commander of a division of strategic bombers stationed in Estonia. Dudayev was the first Chechen to reach the rank of a general in Soviet history. The high-ranking guest lent a shine to the proceedings—a career in the Soviet army in Chechnya. Dudayev was basically a foreigner to his own land. He was born in Kazakhstan, like almost all of his generation, and made his career in Russia. He was married to a Russian woman and spoke better Russian than Chechen. Nevertheless, and to the surprise of many, the congress voted the high-ranking foreigner in as chairman of the executive committee of the All-National Congress of the Chechen People. Whether this was because Dudayev, as an outsider, was not caught up in the rivalries between local factions or whether his high military rank inspired the delegates, the first national leader of the Chechens in post-Soviet times turned out to be a Soviet Air Force general. Dudayev wholeheartedly embraced his new political career, but it proved to be a short one, with a disastrous end for himself and with most dire consequences for his people. After the 1991 – 1993 Chechen War, when his son was killed in a Russian airstrike.

Flag of the separatist Chechen Republic.

In early September, Dudayev, with a handful of armed retainers, enforced the “self-dissolution” of the now completely powerless Supreme Soviet after the August coup. Power in Chechnya had now in actual fact shifted to the executive committee of the National Congress. The Chechen revolution dismantled all Soviet political institutions more quickly and more thoroughly than did all other national independence movements of the Soviet Union, in part because the institutions of Soviet power had only superficially penetrated Chechen society. Subsequently, however, it was this institutional tabula rasa that rendered the consolidation of the new state impossible.

On November 8, 1991, President Rutskoy declared a state of emergency in Chechnya, which, was then passed by the Russian Supreme Soviet on November 11. On the same day, Russian airborne troops tried unsuccessfully to set foot in Grozny airport, which was blocked by Chechen fighters. The contingent returned to the barracks, and Dudayev held the election and was elected president with 90 percent of the vote. His first decree proclaimed the independence of Chechnya. His newly elected parliament granted him all powers necessary to defend the sovereignty and independence of Chechnya. On November 27, Dudayev contacted Moscow and asked for a peaceful independence for Chechnya. Rutskoy refused to allow Chechnya go independent and so did the Russian Supreme Soviet.

Nonetheless, a ceasefire to make sure that the current exodus of Ukrainians and Russians from Chechnya took place in an orderly format, Rutskoy agreed to not invade Chechnya until the 20th of December, 1991. On that day, around 40,000 Russian troops of the 40th Army entered Chechnya. Though the Russians would win the Chechen War, the failures of the army would prompt the 1995 – 1998 Army Reforms of the Russian Army.

***

***

Chapter 17 of Russian Political History by Cambridge University

On November 8, immediately after the Minsk protocols, President Alexander Rutskoy of the new Russian Union had to form a new government for the newly independent nation if he wanted to survive the inevitable economic and social rupture that would come from the end of the Soviet Union. He decided to form a national unity government composed of politicians from all spectrums of society in a bid to make sure that the country would be able to soften their fall from grace and power.

Grigory Yavlinsky.

As Ivan Silaev resigned as the last Soviet Prime Minister, the issue of the premiership within Russia reared its head. Rutskoy knew that the appointment of the prime minister would play an important role in the economic recovery of the nation decided to call upon someone unorthodox to become the Prime Minister of the Russian Union. Grigory Yavlinsky was in Lviv packing his bags and personal items to move back to Russia as per his Russian citizenship when he received a phone call that evening from Rutskoy himself. Yavlinsky remembers the astonishment in his memoirs completely and vividly. “I was packing my bags, looking after my land tenants, and moving the family when the phone rang. I picked it up, and was surprised to hear the gruff voice of President Rutskoy. He offered me in no certain terms the premiership of Russia. It obviously pained him to ask me, however the desperation of the new unenviable economic position had forced him to turn to me it seemed. I had no other choice. I had to accept.”

Yavlinsky had under the Gorbachev and Yeltsin been an extremely important political figure, both as Department Head of the State Commission for Economic Reforms and as the government’s official economic advisor. He certainly had the reputation and experience for a premiership, and Rutskoy was obviously putting the need of the economy and the government first when he appointed Yavlinsky as Prime Minister of Russia despite his personal distaste of the economist. With the issue of the Prime Minister quickly resolved, on November 9, President Rutskoy submitted a list of potential candidate members for the cabinet to Anatoly Sobchack, the Vice President and Yavlinsky, the newly minted Prime Minister who was on his way back to Moscow via airplane. Most of the candidates were approved by the Vice President and Prime Minister for the National Unity Government, however Yavlinsky replaced Anatoly Chubais as the candidate for the Ministry of Economics and replaced him with Petr Aven, an old economic associate of Yavlinsky. With these measures taken into account, on November 10, Rutskoy formed a new governmental cabinet called the Yavlinsky I consisting of the following peoples:-

- President: Alexander Rutskoy

- Vice President: Anatoly Sobchack

- Prime Minister: Grigory Yavlinsky

- Deputy Prime Minister: Gennady Burbulis

- Minister for Social Policy: Alexander Shokin

- Minister for the Fuel and Energy Complex: Viktor Chernomyrain

- Minister for Atomic Energy: Viktor Mikhailov

- Minister of Security: Viktor Barranikov

- Minister of the Interior: Viktor Yerin

- Minister of Health: Andrey Vorobiov

- Minister of Foreign Affairs: Andrei Kozyrev

- Minister of Foreign Economic Relations: Anatoly Chubais

- Minister of Culture: Yevgeny Sidorov

- Minister of Science and Technology: Boris Saltykov

- Minister of Defense: Yevgeny Shaposhnikov

- Minister of Education: Eduard Dneprov

- Minister of the Environment and Natural Resources: Viktor Danilov

- Minister of Information: Mikhail Poltoranin

- Minister of Railways: Gennady Fadev

- Minister of Agriculture: Viktor Khlystun

- Minister of Fuel and Energy: Vladimir Lopukin

- Minister of Transportation: Vitaly Yefimov

- Minister of Labour: Gennady Melyikan

- Minister of Justice: Nikolay Fyodorov

- Minister of Economics and Finance: Petr Aven

Money supply through fraud also increased by 34% in the country and Russian money supply from overall means of supply grew by 18 times throughout the country. Inflation also ran rampant throughout the country, with average prices in the country already hiking all the way to 245% already. It was becoming clear to the new government that immediate economic measures would need to take place unless the government wanted to have an economic depression on their hands. A sharp decline in economic value had been anticipated by many after the fall of the Soviet Union, but the government would do anything to soften the economic blows.

A flee market in Rostov.

The three main economic actors of the new government were to be Prime Minister Grigory Yavlinsky, Minister for Foreign Economic Relations Anatoly Chubais and Minister of Economics and Finance Petr Aven. Both Aven and Yavlinsly were advocates of a Swedish and Finnish style social democracy and both of them outvoted Chubais regarding the issue of a shock therapy, which Yavlinsky and Aven both found to be unsuitable and irresponsible within the economic context of the newly independent Russian Union. Chubais himself had in 1989 been an advocate of social democratic economics within the Soviet Union before he had changed his tune, and as such it wasn’t hard for the other two economists to change the mind of the man. In coordination with the other members of the cabinet, both Yavlinsky and Aven decided to compile economic statistics to deem the best economic reform needed for the Russian state, and at the same time, Chubais was dispatched to America to the headquarters of the International Monetary Fund to secure a loan which would be used as a stimulus package by the Russian government.

Petr Aven.

On November 15, after five days of intensive economic data collection from throughout the country, Yavlinsky and Aven decided that a mixed economic model based on gradual privatization and social democratic models would be the best suited one for the Russian economy. Yavlinsky amended the 500 Days Program that he had earlier advocated, and amended the program to become a 750 days program. The 750 Days Program which was written down on November 15 and presented to the cabinet on November 20, 1991 was a complete break from existing views, academic concepts, and journalistic economic publications at the time with respect to the interpretation of society’s economic problems. It was the first real attempt in economics to circulate a new radical change in ethical assessment of social and economic phenomena. It was a complete program that predicted the main lines of dissolution in society and correctly pinpointed the crux of possible conflicts on the event of implementation of radical economic reforms such as labor conflicts and wage conflicts, breakdown of the welfare system and regional hurdles of economic development. As such it recommended the following measures to make sure that the economic damage to the country was dampened:-

(i). Compression of wage differentials: Centralized wage bargaining was recommended so that it could lead to low wage dispersion in the labor market and hence lower pre-tax labor income inequality.

(ii). Creative Destruction: Utilizing a high degree of compression of wage differentials, creative destruction would be fostered leading to a large share of highly productive enterprises, which in turn lead to a higher average labor productivity in the state.

(iii). The usage of state capitalism to ensure a productive economy for the time being. The retention of many state owned companies to manage the exploitation of the country’s resources to create and maintain large number of jobs. The usage of sovereign wealth funds to invest extra cash in ways that maximize the country’s profit from the private sector.

(iv) To incentivize foreign investment, the creation of a plan to pre-approve all investment up to 51% foreign equity participation, allowing foreign companies to bring modern technology and industrial development.

(v). To partially dismantle public monopolies by floating shares of the public sector companies and limiting public sector growth to essential infrastructure, goods and services as well as mineral exploration and defense manufacturing.

(vi). The creation of a balanced budget to get the fiscal deficit under control by temporarily curbing governmental expenses. Subsidies to the central Asian republics which were stopped after November 8 were to be collected and gathered in the budget to balance it against deficits. The artificially high rate of exchange for the Ruble was to be devalued from 5.3 to 7.1 rubles per dollar to 6 to 9.5 rubles per dollar in order to increase foreign currency reserves and print more money and stabilize the price crisis in the country.

(vii). To stabilize the macroeconomic trends of the economy to make sure price control can be implemented once again in the Russian Union in a proper manner. The stabilization of the currency is to take place with a stimulus package and injection with aid from the International Monetary Fund and the above devaluation to create confidence in the ruble to make sure that supply bottlenecks aren’t created in the country. A realistic target for inflation to be created. The current inflation rate standing at 245% is to be reduced to 230% by March, 1992, to 200% by October 1992 and onwards after that.

The cabinet approved of the economic plan put forward by the two economists and on November 24, the plan was given to the Russian Soviet of the Republic. The Soviet of the Republic which was a precursor to the Russian State Duma, passed the 750 Days Program with a total of 80 in favor of the plan, 36 in opposition to the program and around 10 deputies abstaining from voting during the deliberations. On November 26, it was declared official policy of the Russian government in regards to the economy.

On November 29, the Russian government successfully managed to gain a $4.2 billion stimulus package from the International Monetary Fund, and negotiations to enter the IMF began between Moscow and Washington. The stimulus package was used to increase the economic stability of the ruble, as had been advised by Aven and Yavlinsky.

***

Chapter 11 of Post-Soviet Drama: The Pandemonium of Nations

The independence of the Soviet republics created an immediate problem throughout the former union. The question of the armed forces, the Security Council seat, the navy and most importantly the question of nuclear weapons. On November 18, the Ukrainian government contacted the Russian government and asked for moderation from the United States whilst managing the matters of the Security Council, and the nuclear weapons of the former Soviet Union. Leonid Kravchuk, the new President of the Republic of Ukraine asked Rutskoy for a meeting in one of the western countries alongside Kazakhstan to end the nuclear question of the former Soviet Union once and for all. Nuclear dissemination had been one of the top policies made by Rutskoy’s government, and Rutskoy agreed to the invitation.

On November 29, Leonid Kravchuk called the Russian government once again and told the Russians “I have spoken with the American government led by President Bush, and he has told me that with deliberation with the other members of NATO, the country of Portugal has agreed to hold a conference for the Ukraine, Russia and Kazakhstan in regards to the nuclear weapons that are residing within our soils. The British, French and Chinese governments have agreed to send delegations to confirm the legal successor of the Soviet Union in the United Nations Security Council. The conference will take place in Lisbon on December 26 and last until December 29.”

Rutskoy gave power to Sobchak temporarily as his vice president as he left the country to meet with the delegations that would be sent to Lisbon to sign and negotiate a treaty regarding the armed forces of the Soviet Union. The signing of the protocol was taken place during the ongoing process of reorganization of the former Soviet Union into the Commonwealth of the Independent States and the creation of a monetary union between the members of the CIS.

Flag of the CIS - Commonwealth of Independent States

In Lisbon, Rutskoy met with Kravchuk and Nazarbayev, as the leaders of the three post-Soviet states which held nuclear weapons within their borders. The Americans had sent James Baker, the US Secretary of State as their delegation to the meeting. On the other hand, the Britain had sent Douglas Hurd, the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, and the French had sent Rouland Dumas, the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, and the Chinese had sent Tang Jiaxuan, the Chinese Foreign Minister of the People’s Republic respectively as their delegates for the meeting. Rutskoy was accompanied by the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Andrei Kozyrev.

The Russian government’s position was clear. It was the legal successor of the Soviet Union, and as the Russians had already taken up the post of the Soviet ambassador in the United Nations, the USSR’s seat in the Security Council, and the nuclear weapons would have to be given to Russia. The nuclear weapons in Kazakhstan and Ukraine were useless for any military action due to their launch codes being in Moscow, however the possibility of independent research into nuclear weapons was a topic that both powers of the USA and Russia wanted to avoid within the borders of Ukraine and Kazakhstan.

James Baker.

The Kazakh and Ukrainian governments wished to have some kind of power over Moscow in the era of independence, and at first both Kravchuk and Nazarbayev refused to hand over the nuclear weapons to Russia, whilst they agreed to recognize Russia as the legal successor to the Soviet Union, and as such take the Security Council seat. Baker would later write in his memoirs, “The tension was fractious. Rutskoy was obviously still angry at the breakup of the union, and the Kazakhs and Ukrainians believed that they held some sway over the Russian government due to their nuclear weapons. However in that situation, Mr. Hurd and Mr. Dumas clearly understood that Russia held the cards. In the situation of a last resort, the Russians could activate the launch codes of the nuclear weapons situated on Ukrainian and Kazakh soil, and detonate them, bringing a rain of destruction down on the newly independent states. Mr. Kozyrev, the Russian Foreign Minister would slap the reality of the situation onto President Kravchuk and President Nazarbayev when he pointed out the reality of the situation. He was a bit crude in the manner that he conveyed the meaning, however it got the point across.”

Relations between the new independent states were already cold, as the conflicting personalities of the new leaders clashed against one another and the subtle threat of Russia irredentist claims in Ukrainian Donetsk and Luhansk, and in Kazakhstan, which was at the time Slavic majority was not spoken aloud, however it was understood by everyone present. The Kazakhs and Ukrainians would not be able to use the nuclear weapons they possessed to any meaningful amount if the Russians invaded, and the loyalty of the Ukrainian Armed Forces and the Kazakh Armed Forces, consisting of many ethnic Russians was also largely suspect in such a scenario. Kravchuk caved first, and agreed to return the nuclear weapons if he got a concession out of Russia regarding Ukrainian sovereignty. He demanded a perpetual Russian guarantee of Ukrainian territorial, diplomatic and political sovereignty. Rutskoy agreed to give this concession whilst the Kazakhs demanded the same. Rutskoy agreed to extend the offer to the Kazakhs as well.

On December 28, 1991 the Lisbon Protocol was typed down by the parties present and laid down the following major points:-

- Articles [1-3] introduced the situation that was present on the ground within the three countries, and laid out that the Ukrainians and Kazakhs would return the nuclear weapons they possessed to Russian control by the end of 1992.

- Articles [4-5] also dealt with the fact that the Russians were now guaranteeing the political, territorial and diplomatic sovereignty of the Republic of Ukraine and Republic of Kazakhstan

- Articles [5-8] confirmed the Union of Russia as the diplomatic and legal successor state to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, taking up their institutions in the United Nations and their seat in the Permanent Council of the Security Council.

- Articles [9-10] confirmed that the Russian government would continue to adhere the 1968 Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.

- Articles [11 – 15] dealt with the division of the Soviet Armed Forces on the basis of regional locations and the ethnic enlistments in the armed forces dependent on citizenship of the troops.

***

Chapter 16 of The Question of Transnistria and Gagauzia.

Before the Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, and the creation of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1940, Bessarabia had been a part of Romania after World War I and a part of the Russian Empire before that. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany which led to the Soviet annexation of Moldova was declared null and void by the Moldovan Supreme Soviet and they declared independence on the 27th of August 1991 like so many of the other republics within the Soviet Union. Before the creation of the Moldavian SSR, the territory that made up Transnistria was a part of Ukraine and only added to Moldova in 1940.

During the last years of the 1980s, Gorbachev’s Perestroika and Glasnost allowed political pluralism at the regional level. In the Moldovan SSR, the nationalist movement became the leading political force as a result. As these movements exhibited increasingly nationalist sentiments and expressed an intent to leave the USSR and uniting with Romania, these movements encountered growing levels of opposition from the primarily Russian and Ukrainian ethnic minorities living in the Moldovan SSR. The opposition was extremely strong within the boundaries of Transnistria, where the ethnic Moldovan population was outnumbered by the general Slavic population, largely due to the history of Russian and Ukrainian settlement in the region, with links going as far back as the Russian Empire and continued under the Soviet Union.

On 31 August 1989, the Supreme Soviet of the Moldavian SSR enacted two laws. One of them made Moldovan the official language, in lieu of Russian, the de facto official language of the Soviet Union. It also mentioned a linguistic Moldo-Romanian identity. The second law stipulated the return to the Latin Romanian alphabet instead of the soviet introduced Cyrillic script. Moldovan language was the term used in the former Soviet Union for a virtually identical dialect of the Romanian language during 1940–1989. On 27 April 1990, the Supreme Soviet of the Moldavian SSR adopted the traditional tricolour (blue, yellow and red) flag with the Moldavian coat of arms and later changed in 1991 the national anthem to Deșteaptă-te, române!, the national anthem of Romania since 1990. Later in 1990, the words Soviet and Socialist were dropped and the name of the country was changed to "Republic of Moldova".

The flag of Transnistria.

These events, coupled with the opening of the Moldovan-Romanian border led many in Transnistria to believe that political union between Moldova and Romania was inevitable. This possibility created ethnic fears in the Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian and Bulgarian community in Transnistria that they would be excluded from most aspects of public life as had been the case in the Baltic countries where their ethnic Russian and Slavic populations were becoming increasingly sidelined. From September 1989, strong scenes of protest broke out all across the Moldovan Republic, but mostly in Transnistria, against the central government’s ethno-centrist policies. These protests soon developed into the formation of secessionist movements in Gagauzia and Transnistria, both of whom had initially sought to remain as autonomous regions in Moldova, however the nationalist dominated Moldovan Supreme Soviet outlawed the initiatives presented by the Transnistrians and Gagauzians. After this, the Gagauz Republic and the Republic of Transnistria declared their independence from Moldova and announced their intention to be reattached to the Soviet Union as independent federal republics.

In the aftermath of the 1991 August Coup in the Soviet Union, the Moldovans achieved full independence, and in Tiraspol, the Transnistrian government decided to conduct a full independence referendum. On November 6, Igor Smirnov, the leader of the Transnistrian independence movement, declared that an independence referendum would be held by the Transnistrian government on the 6th of December, 1991. He also mandated a legislation that made it necessary for all able voters to attend the referendum if they were in the (unrecognized) country.

Igor Smirnov of Transnistria.

Smirnov sent invitations to the Ukrainian, Russian, Romanian, Hungarian, American, British and French governments to send supervisors to the referendum to make the referendum result’s legitimate, as he was sure that the secessionists would win. The Russians and Ukrainians agreed to send delegations to the referendum as supervisors, whilst the rest declined, as the western powers and the newly independent Romanian and Hungarian governments did not wish to alienate the Moldovan government, with whom they were trying to cultivate good relations with. President Rutskoy himself was a supporter of Transnistrian and Gagauz independence, and asked the Russian Supreme Soviet to write a legislation in favor of the two gaining full sovereignty. The Ukrainians and Leonid Kravchuk also tacitly supported the two secessionist movements.

On December 6 the referendum took place, and around 97.81% of all correspondents voted in favor of independence. Even much of the ethnic Moldovan populace of Transnistria voted in favor of independence. Alexander Cooper, a British reporter who worked for the BBC in Moldova during this time remembers, “The Moldovans in the region were perhaps just as fanatic about independence. The Moldovans of the region may have spoken Romanian-Moldovan, however they had lived in an ethnically diverse region, and many were related to the Russians and Ukrainians of the region who would be adversely affected by political union with Romania. As a result, familial loyalty played a large role in making even the ethnic Moldovans vote in favor of independence. There is no doubt that the referendum was rigged by Smirnov, however even a free and fair referendum would have ended in favor of independence. Of that there is no doubt either.”

In the Gagauz Republic, their new President, Stepan Topal was insistent that he would use democratic means of gaining independence, and stated that a referendum would be held on January 17, 1992, and asked the United Nations to intervene and send representatives to supervise the referendum whilst he sent invitations to all of the Commonwealth of Independent States as well. Topal would not receive UN representatives, however Russian and Romanian meddling in Moldova would ensure that he held the referendum in the end, regardless of the lack of representatives of the international organizations.

***

Chapter 6 of The Battle for Dominance in Post-Soviet Caucasus.

In 1991, Chechnya declared its independence from Russia on a unilateral basis. This immediately provoked Russian response, as was expected. Chechnya is situated in the northeast region of the Caucasus. To the east, north, and west, the republic borders with the Russian regions of Dagestan, Stavropol’ krai, Ingushetia, and North Ossetia; to the south, it borders with Georgia. Its territory encompasses 15,678 km. About one-third of the territory is in the plains north of the Terek River, which crosses Chechnya west to east. The southern part of Chechnya, covering another one-third of the total territory, is mountainous—the highest mountains are over 4,000 m high—and poorly accessible. The capital, Grozny, was founded in 1812 as a military outpost of Russian colonialism in the North Caucasus and aptly named “the threatening.” It and the other larger settlements—Gudermes, Shali, and Urus-Martan—all lie in the middle part of Chechnya, between the mountains in the south and the Terek Plains in the north. Most of the intensive fighting took place here; rebels used the mountains in the south as their safe retreat and as a lifeline for military supplies. A large part of the military supplies was brought over mountain paths from Georgia, Dagestan, and Ingushetia.

The available demographic data for prewar Chechnya are not very precise. The reason for this is that, until 1991, Chechnya, together with the much smaller Ingushetia, constituted the Chechen-Ingushetian ASSR. All data from the Soviet Census of 1989 thus relate to the Chechen-Ingushetian ASSR. Extrapolating from the data in the Soviet Census, it can be estimated that, in 1991, the population of Chechnya proper was around 836,000, of which about 700,000 were ethnic Chechens and the rest were predominantly ethnic Russians.

Despite the particularly ferocious attempts at Sovietization, Chechen society, perhaps more than other Caucasian societies, has proved itself to be particularly resistant. In key areas, such as law and justice, loyalty and solidarity, and religion and identity, traditional forms of local organization were preserved. Older Chechens relate that, after the Stalin era, no Chechen was ever brought before a Soviet court of law charged with a serious crime. Instead, the law was administered according to the traditional legal canon, the adat, and enforced by the clans. Such tales may be exaggerated, but they highlight the extent to which traditional ideas about law, as well as traditional procedures for its enforcement, were preserved during Soviet times. Islam, the source of much of customary law called adat, also resisted Soviet atheist campaigns. Adherence to Islam remained an important part of Chechen cultural identity, even if the open practising of religion was not possible in the Soviet Union. The considerable resistance of Chechen society toward Soviet institutions and Soviet culture brought about the parallel existence of two normative systems. This strange juxtaposition of contrasting, often mutually exclusive, norms and procedures, present in all Soviet societies, was particularly prominent in Chechnya. The fact that, to a large extent, the Chechens were sidelined in terms of opportunities in the Soviet Union, made the system even more entrenched. In the Soviet Union, it was difficult to have a career as a Chechen. Even within their “own” republic, key political and economic positions were by and large beyond the reach of Chechens. This was in contrast to other ethnic republics, in which representatives of the titular nation had good career chances up to a certain point. For this reason, the emergence of a Chechen-Soviet elite took place very slowly. Thus, after 1991, a class of decision-makers, who were able to stabilize the political situation and ensure a relatively conflict-free transition in many Union republics and autonomous territories, was lacking in Chechnya.

Dhzokar Dudayev.

In November 1990, an All-National Congress of the Chechen People was convened in Grozny. There, 1,000 delegates, each representing 1,000 Chechens living in the Soviet Union, met to debate the cultural and national concerns of the Chechen people, its future, and its past. This was an unprecedented event, made possible by the spirit of glasnost and perestroika that had led to national mobilization throughout most capitals and most borderlands of the Soviet empire. Among the congress’ many guests of honor was one Dzokhar Dudayev, at the time commander of a division of strategic bombers stationed in Estonia. Dudayev was the first Chechen to reach the rank of a general in Soviet history. The high-ranking guest lent a shine to the proceedings—a career in the Soviet army in Chechnya. Dudayev was basically a foreigner to his own land. He was born in Kazakhstan, like almost all of his generation, and made his career in Russia. He was married to a Russian woman and spoke better Russian than Chechen. Nevertheless, and to the surprise of many, the congress voted the high-ranking foreigner in as chairman of the executive committee of the All-National Congress of the Chechen People. Whether this was because Dudayev, as an outsider, was not caught up in the rivalries between local factions or whether his high military rank inspired the delegates, the first national leader of the Chechens in post-Soviet times turned out to be a Soviet Air Force general. Dudayev wholeheartedly embraced his new political career, but it proved to be a short one, with a disastrous end for himself and with most dire consequences for his people. After the 1991 – 1993 Chechen War, when his son was killed in a Russian airstrike.

Flag of the separatist Chechen Republic.

In early September, Dudayev, with a handful of armed retainers, enforced the “self-dissolution” of the now completely powerless Supreme Soviet after the August coup. Power in Chechnya had now in actual fact shifted to the executive committee of the National Congress. The Chechen revolution dismantled all Soviet political institutions more quickly and more thoroughly than did all other national independence movements of the Soviet Union, in part because the institutions of Soviet power had only superficially penetrated Chechen society. Subsequently, however, it was this institutional tabula rasa that rendered the consolidation of the new state impossible.

On November 8, 1991, President Rutskoy declared a state of emergency in Chechnya, which, was then passed by the Russian Supreme Soviet on November 11. On the same day, Russian airborne troops tried unsuccessfully to set foot in Grozny airport, which was blocked by Chechen fighters. The contingent returned to the barracks, and Dudayev held the election and was elected president with 90 percent of the vote. His first decree proclaimed the independence of Chechnya. His newly elected parliament granted him all powers necessary to defend the sovereignty and independence of Chechnya. On November 27, Dudayev contacted Moscow and asked for a peaceful independence for Chechnya. Rutskoy refused to allow Chechnya go independent and so did the Russian Supreme Soviet.

Nonetheless, a ceasefire to make sure that the current exodus of Ukrainians and Russians from Chechnya took place in an orderly format, Rutskoy agreed to not invade Chechnya until the 20th of December, 1991. On that day, around 40,000 Russian troops of the 40th Army entered Chechnya. Though the Russians would win the Chechen War, the failures of the army would prompt the 1995 – 1998 Army Reforms of the Russian Army.

***

Last edited:

Love the amount of details you have put in. Just wondering how has the rest of Europe and the United States reacted to the collapse of the Soviet Union and the new Russian Government?

that will be covered in a future chapter, don't worry!Love the amount of details you have put in. Just wondering how has the rest of Europe and the United States reacted to the collapse of the Soviet Union and the new Russian Government?

Indeed, they are being quite stubbornAlready, things are tense between the former USSR states. Kazakh and Ukraine being stubborn goats are quite expected as they're the ones who've been the holdout of many, many, Russian weapons and nuclear tests.

Indeed............Once more into the Chechnyan breach....

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Share: