What if Max accepts Ex-Confederates more openly and the liberals get the US eventually to actively help get rid of them, and Max. The idea here, and the trickiest part, is to get the US and a competent Mexican government to work together and at least semi-support each other. If racial attitudes soften a little bit in this TL then it may be possible for the US to be more open to working with their southern neighbor but it’s still a long shot.As I understand it, the problems that the Second Mexican Empire strikes me as something like the Vietnam War. The Second Mexican Empire, like South Vietnam, initially enjoys the support of a conventionally powerful ally that will later pull out while there is troubling issue of an ideologically opposed enemy to the north and south that are backed by a powerful ally. (Please do not let this comparison degenerate into a flame-war about Vietnam)

I wouldn't say that the survival of the Second Mexican Empire is impossible but there are plenty of things to consider:

That said, I don't think survival is impossible. The Confederate exiles were used very poorly by Maximilian and Bazaine. When they entered Mexico, they were not allowed to join the French Army or the French Foreign Legion, so many of these guns-for-hire simply joined the Republican rebels. The increased fear of the Radical Republican plans and the USCT may compel more Confederates to flee to Mexico than OTL. An earlier Union victory or perhaps the threat of it may compel Maximilian to form an actual army. That said, a stable Mexico probably requires the Mexican Republican rebels to accept peace or a compromise. I am not familiar enough with Mexican political figures to say if this is possible or not, but certainly avoiding a military collapse would be a good start to negotiations.

- There are a lot of important and powerful Americans who wish to see the Second Mexican Empire gone. Grant and Sheridan saw the Second Mexican Empire as a violation of the Monroe Doctrine and therefore sought to send arms and weapons to Juarez's Republicans. Grant went as far as to plan the involvement of a US Corps with Juarez's army to evict the French Army. There were even skirmishes between the U.S. Army and Imperial forces. Only Sherman seemed okay with the existence of a Second Mexican Empire, writing "I don't see that we are damaged." The purchase of U.S. arms is further aided by two bond guarantees of $30 million dollars from private investors in 1865 (thanks in part to Lew Wallace).

- As time goes on, Maximilian wants and needs to distance himself from the French Army, but he also needs it. It also occurs to me that the French Army becomes increasingly ineffective. With the introduction of U.S. support, the Mexican Republican guerillas intensified their attacks on French supply lines. French battalions, mixed with Mexicans, Austrians, Belgians and even Arabs, were becoming rapidly demoralized, which is rather common during a guerilla war. The imperial troops are demoralized from the lack of coherent objectives, timetables, the lack of physical comfort and communication from HQ.

- Maximilian and the Imperial military leadership really do not see eye to eye. Maximilian was excessively lenient with captured guerillas while Marshal Bazaine favored draconian measures, the most infamous being the "Black Decree" - any prisoners were to be executed. Maximilian signed the law after receiving pressure from the military and it turned out to be a grave mistake. Prisons were filled with alleged bandits and people with Republican sympathizers; the number of widows rose rapidly; and it only inspired the men to flock to the Republican rebels to exact their retribution.

- There's also the issue that the French Army was bound to leave and the French did nothing for a transition of power to the Mexican army. Aside from the French pull out, the expected Austrian reinforcements of 2,000 volunteers to Imperial forces were cancelled owing to threats from the United States. Maximilian also seemed to have been in denial over the possibility of a pullout of European forces and thus had not given much thought to the formation of a Mexican Army.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid: A More Radical American Civil War

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"You mean a foreign monarch imposed by a foreign power with literally zero genuine domestic support and legitimacy would have led to a more stable Mexico, don't you??max winning would set a bad precedent but..how about his forces and juraez have a salmate .both then hold negotiations and create the first modern consitutnal monarchy. you could change some things in the past inorder to make the war less heated and make everyone more willing to sit down

a brutal salmate would avoid the bad precedent and set up a more stable mexico.

I'm not sure that I've seen a TL with a surviving Maximilian that didn't also have a victorious Confederacy (with some level of UK/FR support).You mean a foreign monarch imposed by a foreign power with literally zero genuine domestic support and legitimacy would have led to a more stable Mexico, don't you??

My lord hand ,You mean a foreign monarch imposed by a foreign power with literally zero genuine domestic support and legitimacy would have led to a more stable Mexico, don't you??

First I was speaking On thr authors wishes and a way from them to proceed and result in prosperity. My own dream perfect timeline would see mexico avoid the first coup by having itrbtuide not be a dickhead or secondly have no war between the revoulntories after overthrowing Diaz.

As for yout points

The archduke had some popular support[http://www.sudd.ch/event.php?lang=en&id=mx011863] fairly decent.If a modern presidential candidate had that support they'd be considered a frontrunner and in america win the electoral collage.

It’s all good, you shouldn’t feel bad about trying to contribute to the conversation and certainly not feel bad about not reading all 4200+ posts so far. I apologize if my post made you feel as if you did anything wrong.

No worries.

Graying Morality: Inverted. The Union becomes less racist and the Confederacy more so overtime as the war radicalizes both factions.

Also played straight with each side increasingly tolerating the atrocities of its partisan supporters.

Just started reading this.

Democrat, no?Illinois had heretofore been a reliably Republican state

reverted to territories, no?Southern States had forfeited their rights and reverted to states

I've got nothing to add about Mexico. I appreciate everyone's contributions and will come back to this part of the discussion in the future when I decide what to do. For now, I'll focus on the US.

Wow, I really need a beta reader! Thank you for catching that. I'm going to correct it immediately.Just started reading this.

Democrat, no?

reverted to territories, no?

Chapter 42: And Down with the Power of the Despot!

Though the failure to defeat the rebels at Mine Run and Dalton prevented the Union from bringing the war to a close in the later half of 1863, these battles could hardly dim the glory of the “great trinity” of victories: Lexington, Liberty and Union Mills. Thanks to them, the Lincoln administration seemed secure in the war issue, with its opponents in shambles, routed politically and psychologically after the traumatic Month of Blood and the ensuing repression. Just a few months ago, it had seemed like several Northern governorships could fall into Copperhead hands, dealing the Union cause a hard blow it possibly could not recuperate from. Now, no one doubted that victory would shortly come, and consequently the Republicans, both at a national and state level, decided to start the work of Reconstruction.

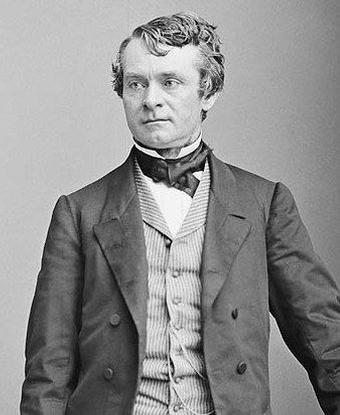

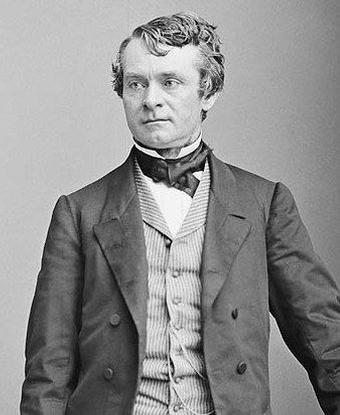

The Republicans’ will and confidence was reinforced by the results of the 1863 elections, namely, their triumphs in Ohio and Pennsylvania. Previous to Union Mills, National Union conventions had named Clement Vallandigham as their candidate for Ohio governor. As the leader of the increasingly powerful Copperhead wing of the party, Vallandigham naturally conducted a pro-peace campaign that called for an immediate end to the war. The Copperhead candidate in Pennsylvania, state supreme court judge George W. Woodward, was less outspoken about his views, but these were just as outrageous as Vallandigham’s to Union men. Not only did Woodward believe that an armistice was the only way to secure reunion, he also had authored a judicial decision that had declared the draft unconstitutional, and, privately, had called slavery a blessing and said that he wished Pennsylvania had joined the Confederacy.

Woodward and Vallandigham’s views were no longer acceptable after Union Mills had reinvigorated the Union cause, and especially after the Month of Blood brought terrible opprobrium and punishment upon the opponents of the war, whether they were guilty or not. Vallandigham, who had conspired with rebel agents and acted as a “wily agitator” that encouraged desertion and sedition, was certainly guilty. Woodward, not so much. Still, both men had to flee the nation, Vallandigham running to Canada after a military tribunal indicted him, and Woodward deciding to tour Europe, citing health reasons but confessing privately that he feared “being tarred and feathered, or worse, by the abolition mob”. Woodward’s fears were not entirely unjustified, as in the aftermath of the Month of Blood many Copperheads were targeted for abuse or even assassinated.

The flight of their most prominent leaders and the attacks and abuse their rank and file received meant that the Chesnut organizations were practically destroyed in several areas and even in entire states, paving the way for complete Republican dominance. Even War Chesnuts were reluctant to continue being members of a party “that had revealed itself to be a hidden rebel army”. This did not necessarily mean switching to support the Republicans, who were regarded as equally, if not more, extreme. But it did mean that War Chesnuts abandoned the party in increasing numbers, unwilling to support peace and oppose the administration if that signified support for rebellion and massacre. If blood spilled in far way Kansas could be ignored and guerrillas in Tennessee dismissed, the gory scenes of New York could never be forgotten. Whether to save themselves or out of principle, War Chesnuts deflected from the National Union, leaving it a hollow and feeble organization.

George Washington Woodward

In some states, the War Chesnuts attempted to create their own organizations in order to continue their opposition to the Lincoln administration’s aims but not to the war itself. However, the very idea of a loyal opposition had been destroyed by the month of blood. At the start of the July session, Stevens already pleaded with his colleagues not to admit the “hissing copper-heads . . . until their clothes are dried, and until they give back the grey uniforms John Breckinridge smuggled into New York and Baltimore. I do not wish to sit side by side with men whose garments smell of the blood of my kindred.” Heeding Stevens’ advice “for perhaps the first time but certainly not the last” as a radical newspaper said gleefully, the Congress expulsed some lawmakers “notorious for their sympathies for treason and butchery”. It never became a complete purge due to Lincoln and the moderates’ objections, but it strengthened the Republican supermajorities and created a mood of prevailing radicalism that helped along in the passage of the Third Confiscation Act.

This coup de main against Chesnut power at the Federal level had its repercussions at the state level too, as the party found itself void of leadership and clear objectives. As the campaign developed, their greatest flaw, their inability to form a coherent message, came to the forefront again, as different factions struggled for power with perhaps more animosity and bitterness than they showed the Republicans. In Ohio, Vallandigham continued his quixotic campaign for governor from his exile in Canada, this despite the attempts of both War Chesnuts and Copperheads to replace him with another candidate. In Pennsylvania, no less than four other candidates threw their hats into the ring, coming from such parties as Constitutional Re-Union, American, Liberty, and Constitutional Union. Alongside Woodward’s still standing National Union candidacy, the result was a grand total of 5 politicos of Democratic origin against the candidate of the united Republican Party.

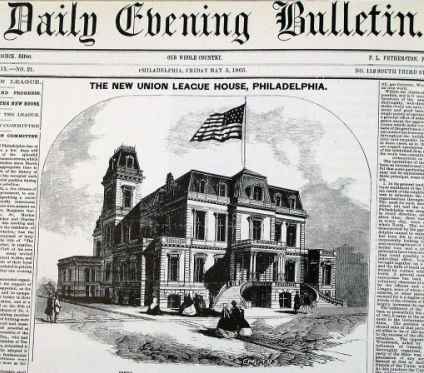

“Our party is shamefully divided”, despaired a Chesnut voter in Pennsylvania. “The petty struggles of petty men assure our defeat before the tyrant.” But even if petty struggles weren’t enough to assure the Chesnuts’ defeat, several paramilitary groups were ready to take extralegal or even illegal measures to do so. Though they sometimes called themselves Wide-Awakes as a call-back to the 1860 election, the name most commonly claimed by these new clubs was “Union League”. They first appeared in the 1862 elections, where they were little more than Republican debate clubs and printing societies. But as the war radicalized and especially following the Month of Blood, the Union Leagues took a more assertive course. They never became guerrillas or were as brutal as Chesnuts said they were, but they certainly weren’t above using violence or intimidation against the enemies of the government, who were widely seen as just traitors instead of a legitimate opposition.

Similar to how the Confederate guerrillas are the predecessors of the Ku Klux Klan and other terrorist organizations that sought to overturn the new Southern order during Reconstruction, the war-time Union League was the forerunner of several paramilitaries that operated in both North and South with the aim of stamping out disloyalty and defending the gains of the war. Sometimes preserving the Union League name, sometimes changing it to Equal Rights Association or similar, the Southern Union Leagues of Reconstruction were far more radical in methods and objectives, which is explained by the brutality of their foes. Even more moderate political organizations, such as the Union veterans’ Grand Army of the Republic, were profoundly influenced by the Union League, which informed their determination to defend the new order by any means necessary.

The Union Leagues would face terrorist organizations like the Klan during Reconstruction

Several Republican leaders, both during the war and after it, lamented the methods of the Union League. Lincoln himself appealed to their “love for democracy and respect for the Constitution” to try and quiet down overt violence. But Lincoln and other Republican authorities proved unwilling to actually take hard measures against them, because even if their methods were misguided, they agreed with their objectives. The “ghost of old John Brown” seemed to manifest once again, as Republicans took an aptitude similar to the one they had once taken towards that abolitionist warrior: condemning the violence, but lauding it as brave and just. Consequently, even as Republican military and state authorities brought their power to bear against the Sons of Liberty and similar Copperhead associations, the Union League was allowed to guard voting stations, intimidate Chesnut politicians, and even assault particularly outspoken Copperheads. The Republicans, a Chesnut voter wrote in anguish, had “inoculated the general mind with ideas which involve . . . the acquiescence of the community in any measures that may be adopted against the National Union.”

The tacit acceptance of these events by the Lincoln administration came partly from the knowledge of how pivotal the fall elections were. With the process of Reconstruction starting in the Border and the Deep South, and the ink of the radical Third Confiscation Act still fresh, the President and his party wished for a vote of confidence before pressing onward with their objectives. They also believed that such a show of unity and political power was needed to break the Southern spirit and convince the Northern people that they had to fight for unconditional victory. “All the instant questions will be settled by the coming elections,” commented a Lincoln supporter. “If they go for the Rebel party, then Mr. Lincoln will not wind up the war [and] a new feeling and spirit will inspire the South.”

As was customary, Lincoln did not campaign actively, though he and his government took measures to aid the Republican campaigns. In Kentucky, for example, the military authorities, together with the radicals that had taken over the state government following Bragg’s campaign and the Month of Blood, arrested thousands of Chesnut candidates and voters, helping secure the victory of the candidate backed by the administration. Soldiers were furloughed and rushed to Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois and other states to vote the Republican ticket, and Secretary Chase rallied financiers who had made their wealth through government contracts into helping the Republican candidates. While the President could hardly believe that “one genuine American would, or could be induced to, vote for such a man as Vallandigham”, the threat of Copperhead victory was palpable enough for him to overlook the Union League’s actions and aid in these improper, if not illegal, maneuvers.

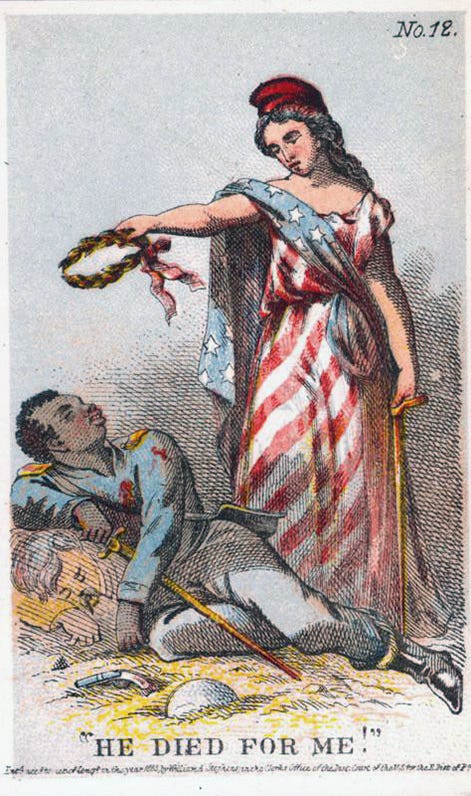

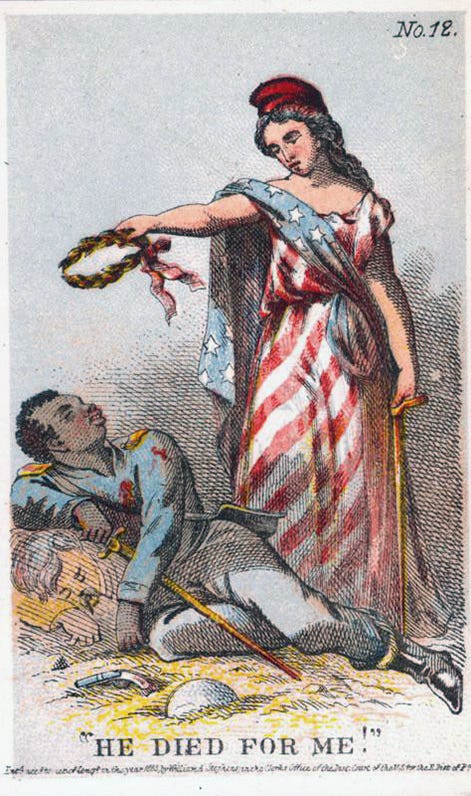

The clear opposition of the administration and the Union Leagues, and the fatal internal divisions that affected the party, already stacked the odds against the National Union. But even without these factors they would have found it difficult to win the election, for their “tried and true issues” had lost their luster. In vain did Chesnuts try to rally their votes to cries of “let every vote count in favor of the white man, and against the Abolition hordes, who would place negro children in your schools, negro jurors in your jury boxes and negro votes in your ballot boxes!” In the aftermath of Union Mills, and with Black soldiers having also fought gallantly at Liberty and Mine Run, such overt racism seemed unpatriotic. Loyal publication societies and local chapters of the Republican party distributed pamphlets contrasting “the gallant colored soldiers of the Miracle at Manchester” with the “cowardly white traitors of the Massacre at Manhattan”. In a brilliant propaganda coup, a Republican speaker in Pennsylvania campaigned with a Black soldier that had lost his leg at Union Mills, yelling “he gave his leg for your liberty! Won’t you give your ballot for his?” “Campaigning with a Negro”, a Republican voter said in awe, “would have been political suicide a mere year ago . . . these are signs of great change.”

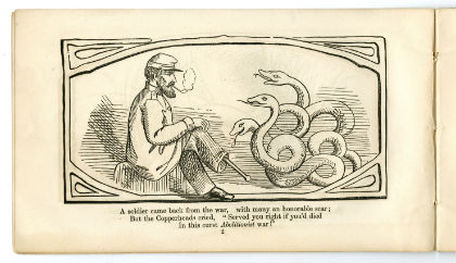

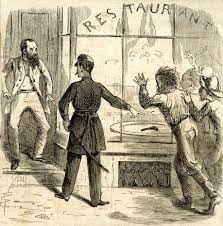

Copperheads were reviled as traitors and supporters of the rebellion.

Other Chesnut issues likewise lost their potency during the 1863 campaign. Speeches against martial law and military tribunals, which had sought to portray them as unnecessary and unconstitutional, now seemed weak and duplicitous when the Month of Blood had proved that Lincoln was right, that there was a fifth column of Confederate sympathizers in the North. Attacks against conscription fell flat, and appeals for peace, now presented as an effort to end the war sooner by offering the already defeated Confederates an opportunity to surrender honorably, were ineffective. Not even the reversals at Dalton and Mine Run were capable of rescuing the Chesnuts from electoral disaster. Divided and attacked, the Chesnuts seemingly gave up towards the end of the campaign season, and the result was an overwhelming Republican triumph.

In Ohio, the Republican candidate won with almost 70% of the votes, while Vallandigham achieved less than 15%, other Chesnut candidates taking the rest. As Secretary Chase happily said, Vallandigham’s defeat was “complete, beyond all hopes”. In Pennsylvania, Governor Curtin was reelected triumphantly with over 60% of the vote, Curtin informing Lincoln that “Pennsylvania stands by you, keeping step with Maine and California to the music of the Union.” And Republicans took supermajorities in the New York legislative elections. Even the Chicago Tribune, a pro-Union journal that was nonetheless highly critical of Lincoln, now called him “the most popular man in the United States” and predicted that if an election were held right then “Old Abe would . . . walk over the course, without a competitor to dispute with him the great prize which his masterly ability, no less than his undoubted patriotism and unimpeachable honesty, have won.”

Republicans and Chesnuts alike interpreted the elections as an endorsement of emancipation and a war for Union and Liberty till complete victory was achieved. “There is little doubt that the voice of a majority would have been against” the Emancipation Proclamation when it was first issued, a Springfield newspaper commented. “And yet not a year has passed before it is approved by an overwhelming majority”. A New York Republican was awed by “the change of opinion on this slavery question . . . is a great and historic fact . . . Who could have predicted . . . this great and blessed revolution? . . . God pardon our blindness of three years ago.” Buoyed by this success, Republicans started to entertain plans for Reconstruction, though the initiative was taken by those in the Border States, specifically, the Marylanders.

Maryland’s unique position as a state with a significant White Unionist element that had been liberated relatively fast by the Federal Army seemed to make it a perfect ground for a “rehearsal for Reconstruction”. However, the state had been devastated by continuous campaigning and several important battles, including Anacostia, Frederick and Union Mills. Fortunately for the Unionists of the state, most of the devastation had been inflicted against the Chesapeake counties that were the base of the slaveholders’ political and economic power in the antebellum. The presence of the Union Army, the mobilization of its sizeable Free Black community, and abolitionist feelings among its white inhabitants contributed to the undoing of slavery as a viable institution in Maryland. By 1863, most Marylanders had concluded that slavery was dead and that new classes of people had to be brought to power, but as in the rest of the South there were sharp disagreements over how slavery was to be liquidated and what role, if any, Black people were to play in the new order.

Maryland’s transformation was punctuated by the help of many Northern politicians and activists that came to the state as “heralds of Yankee culture” that sought to aid it in its transition to free labor. Reformers of an idealistic stripe known as the “Gideonites”, these emissaries brought with them new ideas and a genuine desire to uplift the freedmen and help along in their education and progress. They were most influential in the South Carolina sea islands, where an experiment in black land ownership was being conducted, though their power, both there and in Maryland, was limited when compared with Treasury officials and army officers. Nonetheless, the Gideonites gathered great publicity around their efforts, which helped promote the redistribution of land to the former slaves and encourage the growth of a Republican Party in Maryland.

Andrew Curtin

Leading the Maryland radicals was Henry Winter Davis, a representative that bitterly opposed Lincoln because the President had sustained his enemies in the Blair clan, though Davis was somewhat mollified when the Blairs broke with the administration in the aftermath of the Emancipation Proclamation. When a Constitutional Convention was called early in 1863 after the victory at Anacostia seemed to secure the state once and for all, Radicals swept to power, partly aided by the memory of the recent campaign, partly by loyalty oaths administered by the military. The main concern of the Convention was abolition, and, although some conservative Unionists insisted on compensated emancipation, Davis and his men stood firm, declaring that “their compensation is the cleared lands of all Southern Maryland, where every thing that smiles and blossoms is the work of the negro that they tore from Africa.” Immediate, uncompensated emancipation was enacted.

Aside from abolition, the Convention took several progressive steps, aimed at breaking the power of the old planter aristocracy and install in Maryland a system of free labor. Public education was established for the first time, along with progressive taxation and protections against seizure for debt to benefit poor yeomen. But the big question of the era was what was to be done with the enslaved, now freedmen. Though some delegated disclaimed “any sympathy with negro equality”, Davis and his radicals moved to incorporate at least some form of Black suffrage within the state constitution, which arose “such terrible cries” from the conservatives that it had to be removed lest the whole Unionist party collapse.

As the Convention closed with cheers for the “new and regenerated Maryland”, a disgusted Radical declared that none of its work had “been from high principle, … but party spirit, vengeful feeling against disloyal slaveholders, and regard for material interest. There has been no expression, at least in this community, of regard for the negro—for human rights. But even as they were defeated, the radicals could see some glimmers of hope, in that the Convention had decreed equal access to the courts and the law system and abolished the apprenticeship system that bound black minors to white adults, without the consent of their parents, as a half-way to preserve slavery. “We were defeated in the battle for political equality”, Davis admitted gloomily, “but the right triumphed in the battle for civil equality. There is still hope that we may carry this issue to victory in the next great struggle.”

The next battle came sooner than Davis and the radicals could have expected or hoped. Two events aided in this development. First, the rebel victory at Bull Run and the expectative that they could invade Maryland resuscitated pro-Confederate sentiments in Maryland and led the new constitution to defeat. This despite the efforts of the Convention to prevent the disloyal from voting by requiring loyalty oaths and disenfranchising those who had expressed even a mere “desire” for the Confederacy to triumph. But just a month afterwards, the Confederates invaded. The attempt of some Annapolis delegates, some of whom had served as conservative members of the Convention, to throw their lot in with the Confederacy, and the gory riots in Baltimore discredited the conservative Unionists, and, as in the North, made all Republicans identify opposition to their goals as opposition to the war and thus treason. As the dust settled in a Baltimore covered in blood and news arrived of the USCT’s decisive role in Union Mills, Marylanders recognized that a new era had dawned in Maryland.

A second Convention was called, and the Radical victory was even more overwhelming this time. Conservative attempts to portray this effort as one in favor of “free-loveism, communism, agrarianism” failed, and when the Convention assembled the first item in the agenda was not abolition, but black suffrage. Though some Unionist still hoped that they could hold into power through disenfranchisement, and new such measures were indeed enacted, conversation shifted towards giving the franchise to Black Marylanders, who represented 20% of the state’s population. However, even in the aftermath of Union Mills there were many who were not ready for such a momentous step. Acrimonious debate followed, punctuated by racist appeals on one side and politically-motivated praise for the USCT on the other.

At the end, the radicals only managed to achieve limited Black suffrage, for veterans of the Union Army and the literate. But even this limited victory was a great triumph, for, as one delegate admitted “no sane, sober man could have ever predicted that a Southern state would ever give the suffrage to the Negro.” Furthermore, Maryland had furnished a large number of Black soldiers to the Union Army, up to 50% of the eligible Black males, and literacy was higher among its free Black population than in other African American communities. Coupled with this provision was a change in the basis of representation, which would only count voters instead of the entire population – which weakened the plantation counties and made it so that disenfranchisement would only weaken them even more.

The Maryland Constitutional Convention was profoundly influential as a "blueprint" for Reconstruction

Despite widespread disenfranchisement, the new constitution was not sure to pass, because many loyal voters were opposed to “nigger government.” But the ballot was not their only weapon. Armed groups of whites attacked the polling stations where veteran soldiers were casting their first votes, murdering several. Veterans of Union Mills, “the gallant braves who saved our state from rebel rule”, were among those slain. White Unionists were also intimidated, and in a preview of things to come a group of pro-Confederate men started a riot in Frederick that had to be gorily put down by the Federal Army. But this attempt to prevent the Reconstruction of Maryland only resulted in a stronger commitment to its realization on the part of the Union authorities. Lincoln thus suspended the writ of habeas corpus, decreed that those found under arms should be tried as guerrillas, and allowed several Union Leagues to pay the rebels with the same coin. The result was that many people sympathetic to the Confederacy, or suspected of being so, were intimidated or even murdered. Unionists accepted this, saying that “even the most worthless negro is more deserving than a reb", of both the ballot and life itself.

The new constitution was thus approved early in 1864, aided by new disenfranchising provisions and the campaign of intimidation led by the Union Army, and the Union Leagues, by then basically the paramilitaries of the Republican Party. Black veterans, despite hurdles and danger, came out and voted in great numbers, a fact that, a conservative delegate said, “had raised the spirit of old Roger Taney and made his howls heard all over the land.” At the end, the controversial constitution passed by a mere 589 votes, a victory owed to the Black voters who had so enthusiastically endorsed it. But it was also owed to violent repression, leading to never-ending debates over the legitimacy of the referendum and whether the ends justified the noble means. For Republicans, the answer was an unambiguous yes. Nonetheless, the fact that even after employing all these methods the victory was a close one underscored the inherent weakness of the new Republican regime and the resistance of White Southerners to these astounding changes. But these apprehensions were lost among the chorus of jubilant celebrations. Lincoln himself extended his congratulations to “Maryland, and the nation, and the world, upon the event”, and said that “it gratifies me that those who have served gallantly in our ranks are free to vote”.

The Maryland Constitution also had an effect in the rest of the Border South, inspiring the Republicans in those states to take more Radical measures. Their success was limited in Delaware and Kentucky, where old elites retained their grip in power and there were few radical leaders or great events to push them towards change. By contrast, Missouri went in some ways farther than Maryland had done. There, the bloody civil war that raged along the border with Kansas and a large population of abolitionist German immigrants resulted in a particularly strong Republican Party that was greatly embittered against the rebels. What Lincoln called a “pestilent factional quarrel” had divided the state’s Unionists and prevented the enactment of changes, creating two factions, the radical “Charcoals” and the moderate “Claybanks”. Though he sympathized with the Claybanks, Lincoln could not tolerate their willingness to ally with former Confederates in the pursue of political power, and the President would end up backing the radicals because, although they were “the unhandiest devils in the world to deal with”, they were “absolutely uncorrosive by the virus of secession” and had “their faces set Zionwards.”

The President’s support for the Radicals was increased by his break with the Blair clan, which remained influential in Missouri. Still, Lincoln was unwilling to back radical measures, warning that a slave state was like a man with “an excrescence on the back of his neck, the removal of which, in one operation, would result in the death of the patient, while ‘tinkering it off by degrees’ would preserve life.” Helped along by the radical General Curtis, the state’s Unionist, including such leaders as Charles Drake and B. Gratz Brown, started a virtual revolution. When a state Constitutional Convention finally met in middle 1864, it enacted immediate, uncompensated emancipation, mandated black civil equality, and coupled limited Black suffrage with widespread disenfranchisement of former Confederates. At its most extreme, Missouri required loyalty oaths even for teachers, lawyers and ministers and enacted a confiscation plan to redistribute land to the freedmen – a disposition made even more radical by the fact that Black landowners could vote even if illiterate.

In due time, Radicals like Davis, who had “cried like a child when the joyous news arrived”, came to see the achievements of the Maryland and Missouri Constitutional Conventions as not being enough. Radicals left limited suffrage and limited equality aside in favor of universal suffrage and complete equality, and a more vigorous intervention in favor of land redistribution and economic change was stressed. Maryland’s failure to extend education, land and economic opportunities came under attack, while the freedmen, expected to be passive workers whose only involvement in politics was casting Republican ballots when needed, proved to be unexpectedly militant. Alongside the increasing popularity of Black suffrage, even limited one, among Northern Republican circles, these events would define the nascent process of Reconstruction in the Deep South. Republican jubilation was only increased by the Confederacy’s own fall elections, which showed the despair that had overtaken many Confederates and seemed to presage a collapse in their will to continue the war.

After Union Mills, Union propaganda shifted towards a more egalitarian and explicitly pro-abolition message

Lincoln, in a certain sense, had been extremely lucky with the timing of the Northern elections. The 1862 midterms took place when McClellan was at Richmond’s doorstep, and the 1863 elections happened when the glory of the great trinity of victories was still glowing. This led the Republicans to great victories in all these electoral contests. Breckinridge had no such luck. The 1863 Confederate elections took place when southern morale was at its lowest point, and the result was a severe rebuke to his administration. More worryingly, the elections showed an undercurrent of widespread dissatisfaction and even pro-peace sentiments. Hunger and battlefield defeats added fuel to the fire. “I have never actually despaired of the cause”, said a Richmond clerk, “priceless, holy as it is, but my faith .. . is yielding to a sense of hopelessness”.

Discontentment at home also found expression within the ranks. Despite conscription, the Confederacy found it increasingly hard to maintain their ranks full, due to a high number of deserters, which, according to War Department numbers, constituted around a third of the entire Army. As Bruce Levine points out, not all deserters had necessarily lost faith in the cause. Rather, many returned to try and protect their families from violence and starvation. As a woman wrote to her son, “the time past has sufficed for public service, and that your own family may require yr protection and help as others are deciding.” Though “most soldiers away without leave eventually rejoined their units", these desertions, even if temporary, could still deprive the Confederate armies of manpower at critical times.

Unfortunately for the rebels, not all deserters were like that. Some left because they had indeed decided that the war was hopeless. More problematic for the Confederate leadership was the extreme bitterness they expressed against planters and the rich. “The cruellty of the [rich] to the Soldiers famileys is the caus of thear deserting”, a semi-literate Alabamian wrote, and the numbers back this assertion. Throughout the Confederacy the number of deserters rose dramatically, most coming from the mountainous upcountry where support for the Confederacy was weak. Furthermore, a majority of deserters came from poor yeomen families. This combination of distaste for the war and class resentment transformed many deserters into Unionists. Though guerrillas and militias did their best to suppress these “rogues”, they were never entirely successful, the terror they inflicted only solidifying the allegiance of these men. “The condition of things in the mountain districts of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama”, the assistant Secretary of War despaired, “menaces the existence of the Confederacy as fatally as either of the armies of the United States.”

The resentment of poor farmers was compounded by the understandable belief that rich planters, for whose benefit the war had started, were simply not making the necessary sacrifices. A newspaper frankly admitted that the "material issues" of the war were "the interests of the planters", making it "eminently their war". But they still denied any right of the goverment to force them to give up their properties or human chattel to the Army. For Breckinridge this plain refusal to aid the war effort was unpatriotic, short-sighted and unfair. A Georgia Congressman for example criticized those who "give up their sons, husbands, brothers & friends, and often without murmuring, to the army; but let one of their negroes be taken, and what a houl you will hear." Responding to these criticisms, a furious Toombs argued that he and all planters would gladly lend their property as long as it was voluntarily. Their refusal was because the government was trying to force them, injuring their pride and violating their rights. "The solution", Bruce Levine summarizes, "lay not in making greater demands on masters but in making fewer", never mind that the planter aristocracy had never responded to softer measures and gentle requests before.

The plainly seen fact that the rich planters were not matching their sacrifices to the cause with their wealth caused resentment against the planter class, the Confederacy, and the war to spread throughout the population and the Army. This critical situation made it seem likely that people in favor of peace could take control and surrender to the Union. But Breckinridge and his men were decided to prevent this. Though dispirited, the President still retained enough hope and vigor to campaign actively in favor of his men during the elections, a breach of custom that Breckinridge, however uncomfortable, thought necessary. Just a month after the defeat at Union Mills, the call for a convention of “patriotic men willing to support the President and the Army until the final victory is achieved and independence is secured” went out. Though Breckinridge disclaimed being behind it, his close allies were in charge and he certainly approved its actions. The Convention created a formal political party, the National Confederate Party, pledged to “the defense of the Confederacy till the last man of this generation falls in his tracks, and his children seize his musket and fight our battle”.

Many Confederates were threatened with nothing less than starvation

The movement towards explicitly partisan politics alarmed many Confederates, who thought the lack of political parties a strength. But, as analysis by historians like James McPherson has showed, this actually was a source of weakness, for political parties allow the leaders of a country to canalize political energies and rally support for their policies. Thus, while the Republican Party was a firm support for Lincoln and his objectives, Breckinridge had had to contend with a bitter opposition without an organized base of support to resist it. The National Party was an attempt to create such a base, that could grant him the “political artillery” he needed to resist the expected backlash. Moreover, by gathering all his supporters into the Nationalist tent, Breckinridge created a clean and sharp division between those who supported him, independence and White Supremacy, and those who opposed his administration, and, ergo, were in favor of peace and submission to the Union with all its accompanying horrors – that is, slave emancipation and Black equality.

In truth, peace sentiment in the Confederacy remained scattered and disorganized. This is one the ways that the absence of political parties helped the Confederacy, for while the National Union served as a vehicle of Copperhead agitation, there was no party for pro-peace men to take over in the South. A North Carolina woman who begged her governor to “try and stop this cruel war . . . For God sake to try and make peace on some terms and let they rest of the poor men come home and make somethin to eat [for] the sake of suffering humanity” was practically alone in such overt demands for peace. The Tory candidates who ran in opposition to the Breckinridge administration most of the time openly and repeatedly expressed their support for the war and slavery, insisting that their opposition was based in Breckinridge’s mismanagement and incompetency rather than a desire for peace.

As in the North, the Confederate fall elections were marked by political chicanery and the violent repression of dissent. Confederate guerrillas terrorized supporters of peace, who concentrated in the mountainous upcountry that leaned towards Unionism. This transformed Western North Carolina and other areas like Northern Alabama into “bloody swathes, were terror and violence rule the day and not a day passes without a horrendous murder”. Breckinridge, also, employed expert political tactics. For example, the agents of hid Food Relief corps, that brought much needed supplies to struggling Confederate yeomen, always made sure to emphasize that the food came from him. Likewise, he, his wife and daughters paraded in Richmond dressed in homespun (leading to a popular but false legend that the song “The Homespun Dress” was composed in honor of Mrs. Breckinridge), and pro-administration newspapers carried news of how his sons fared in the battlefield, always mentioning how Lincoln’s son, Robert, was not serving the Union. Alongside the debacle of the Twenty Negro Law, and the perception that planters were not contributing their due to the war, this contributed to Breckinridge’s image as the champion of the struggling poor.

Nonetheless, no propaganda could obscure the fact that the war was going badly for the Confederacy, and this translated into electoral defeat. Of 112 representatives, 34 were now explicitly against Breckinridge, while 8 of the 28 Senators were now members of the opposition. The defeat doesn’t seem that severe, as the Nationalists would keep comfortable majorities in both chambers, but this was owed to an “ironic anomaly”: the strong support of the Congressmen from the occupied states. Kentucky, Missouri, Maryland and Tennessee, all completely occupied by the Federal arms but still represented in Congress, returned men who were fierily in favor of the war. Likewise, from the occupied portions of Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi and Virginia, stalwart Nationalist were sent. No elections could take place there, so incumbents just remained in office or “were elected by a handful of refugees from their districts”. Naturally, they all supported war to the bitter end as the only way to liberate their states, providing “the votes for higher taxes that would not be levied on their constituents and for tougher conscription laws that would take no men from their districts”.

Mary Breckinridge, First Lady of the Confederate States

In the rest of the Confederacy, the Tories swept to power, taking the Alabama and Mississippi governorships and a majority of the districts still under Confederate control, including 11 of the 19 congressmen of Georgia and North Carolina. It must be remarked again that these men still supported the war, but their Whig sympathies and “weak secessionist credentials” were ominous signs. Such signs abounded, indeed. In Texas, a hint of class conflict was observed when Pendleton Murrah won the governorship on a campaign that rallied against rich planters. In Georgia, Joseph E. Brown, who had denounced Breckinridge so bitterly and so often, showed that he was “a skillful political tightrope walker”, managing to portray himself as both a war supporter and a “paladin of states’ rights”. Despite attacks against him as an “oily flatterer of the masses”, he achieved a comfortable victory over his Nationalist opponent. But if the re-election of a Tory was bad enough, the 27% of ballots the peace candidate, Joshua Hill, gathered, was even worse, and spoke of great resentment in Georgia’s northern hills.

Through the South, Breckinridge supporters were defeated by disaffected constituents, and replaced by men who were less enthusiastic to the war and outright opposed to many measures needed to win it, such as conscription and impressment. Alabama’s case is particularly revealing, for there the legislature replaced the deceased William L. Yancey, the famous fire-eater instrumental in achieving secession, with a man who had voted against secession. The results were owed to the curious coalition formed between planters and poor men, the only common thread being their opposition to the Richmond regime's policies - the planters believed Breckinridge was unconstitutionally asking them to make sacrifices, and the poor people believed he wasn't asking the planters enough. Happily for Breckinridge this is a shown of a lack of coherence and organization that weakened his enemies, but the losses were still keenly felt. Almost all of the defeated candidates believed they had been “stricken down for holding up the state to its high resolves and crowding the people to the performance of their duty.” As an Alabamian warned the government, these results showed a strong “feeling of doubt & distrust” and a “dissatisfaction of the people with their lawmakers”, caused in part by the alienation of “some poor men” who believed that “the war is killing up their sons & brothers for the protection of the slaveholder.”

Only in North Carolina did the poor people’s discontentment blossom into open advocacy for peace. In that state, which had joined the Confederacy only reluctantly when pushed by Virginia’s secession, William Holden had been organizing a powerful, and to Breckinridge dangerous, pro-peace movement, which based its political strength in the Western part of the state, with few slaves and high resentment against slaveholders. Similarly to how Vallandigham colluded with rebel agents in the North, Holden colluded with Unionist guerrillas such as the Heroes of America, a group whose force was "augmenting their number every day". Attempts to root out these insurgents proved unsuccessful, for they intimidated or commanded the respect of many militiamen. One such cowed officer told Vance that "officers are sometimes shot by them and the community kept in terror". Despite his attempts to stamp out this armed insurgency, Vance found little success, "the popular sentiments" that sustained it remaining "as strong and widespread as ever". A forlorn Vance wrote to Joseph E. Brown that among North Carolina Confederates a "general despondency and gloom . . . prevails.”

The political sympathies of these groups was made clear when the main Nationalist organ in the state, the Raleigh State Journal was destroyed by two hundred guerrilla fighters. As Holden readied for the next North Carolina governor’s election in the summer of 1864, it was clear that his was shaping up to be a reconstructionist campaign, that openly called for North Carolina to secede from the Confederacy and rejoin the Union. As a committed Confederate observed, in the many reunions Holden organized “the most treasonable language was uttered, and Union flags raised.” A Holden supporter even directly told Governor Vance that "we want this war stopped, we will take peace on any terms that are honorable. We would prefer our independence, if that were possible, but let us prefer reconstruction infinitely to subjugation.”

By the end of 1863, and as the Confederacy recouped some confidence thanks to Mine Run and Dalton, Vance had decided that he needed to strike against Holden preventively. Holden’s “Conservative Party” had already secured the election of 5 congressmen who were in favor of peace, and for him to even run, Vance believed, would already be an unmitigated disaster. "I will see the Conservative party blown into a thousand atoms and Holden and his understrappers in hell,” Vance pledged. Breckinridge, for his part, was decided to aid Vance in his efforts to end Holden. The President had sensibly rejected a proposal by Vance of offering peace terms to Lincoln, in a Machiavellian scheme that might defuse the peace sentiment in the South when Lincoln inevitably rejected them, but, Breckinridge pointed out, it would also fatally demoralize the Confederates at home and the soldiers in the field by making it seem like the government was ready to surrender.

The North Carolina Standard was one of the most prominent pro-peace Newspapers

Instead, Breckinridge brought his power to bear against Holden, sending two Army regiments to North Carolina, suspending habeas corpus, and authorizing the arrest of anyone who “uttered disloyal sentiments". Far more extreme was the reaction of the guerrillas and soldiers. Moved by Vance’s declarations that Holden’s plan would result in North Carolinians’ sons being drafted “to fight alongside of [Lincoln's] negro troops in exterminating the white men, women, and children of the South”, soldiers and militia organized a bloody counterattack to retake an upcountry that had seemed until then completely under the control of the Unionist guerrillas. To draw out the guerrillas, Confederate soldiers and militia made "hostages of women and children until husbands and fathers turned themselves in", or even resorted to outright torture. They destroyed Holden’s property, sacked his known pro-peace newspaper the Standard, threatened his life, and devastated the organization of the Conservative Party in Western North Carolina. Holden was finally forced to flee the state towards the Federal lines in Eastern Tennessee, which fatally wreaked the peace movement by apparently showing that all pro-peace men were Lincolnite pawns in favor of the often quite brutal Unionist guerrillas.

The 1863 elections in the South had not destroyed Breckinridge’s grip on power and had showed that many Confederates remained committed to the cause. At the same time, they had demonstrated that there was widespread resentment against the war and the dominant classes of the South. If victories were not forthcoming, these resentments could result in an overwhelming peace movement. Seeking to earn the loyalty of White Southerners and finish the work of emancipation, and moreover inspired by the events in the Border South, Lincoln sent its annual message to Congress on December 8. In this message, a coherent, if not comprehensive, program for the Reconstruction of the Confederacy was articulated for the first time, creating the conditions for a new South when this cruel war is over.

The Republicans’ will and confidence was reinforced by the results of the 1863 elections, namely, their triumphs in Ohio and Pennsylvania. Previous to Union Mills, National Union conventions had named Clement Vallandigham as their candidate for Ohio governor. As the leader of the increasingly powerful Copperhead wing of the party, Vallandigham naturally conducted a pro-peace campaign that called for an immediate end to the war. The Copperhead candidate in Pennsylvania, state supreme court judge George W. Woodward, was less outspoken about his views, but these were just as outrageous as Vallandigham’s to Union men. Not only did Woodward believe that an armistice was the only way to secure reunion, he also had authored a judicial decision that had declared the draft unconstitutional, and, privately, had called slavery a blessing and said that he wished Pennsylvania had joined the Confederacy.

Woodward and Vallandigham’s views were no longer acceptable after Union Mills had reinvigorated the Union cause, and especially after the Month of Blood brought terrible opprobrium and punishment upon the opponents of the war, whether they were guilty or not. Vallandigham, who had conspired with rebel agents and acted as a “wily agitator” that encouraged desertion and sedition, was certainly guilty. Woodward, not so much. Still, both men had to flee the nation, Vallandigham running to Canada after a military tribunal indicted him, and Woodward deciding to tour Europe, citing health reasons but confessing privately that he feared “being tarred and feathered, or worse, by the abolition mob”. Woodward’s fears were not entirely unjustified, as in the aftermath of the Month of Blood many Copperheads were targeted for abuse or even assassinated.

The flight of their most prominent leaders and the attacks and abuse their rank and file received meant that the Chesnut organizations were practically destroyed in several areas and even in entire states, paving the way for complete Republican dominance. Even War Chesnuts were reluctant to continue being members of a party “that had revealed itself to be a hidden rebel army”. This did not necessarily mean switching to support the Republicans, who were regarded as equally, if not more, extreme. But it did mean that War Chesnuts abandoned the party in increasing numbers, unwilling to support peace and oppose the administration if that signified support for rebellion and massacre. If blood spilled in far way Kansas could be ignored and guerrillas in Tennessee dismissed, the gory scenes of New York could never be forgotten. Whether to save themselves or out of principle, War Chesnuts deflected from the National Union, leaving it a hollow and feeble organization.

George Washington Woodward

In some states, the War Chesnuts attempted to create their own organizations in order to continue their opposition to the Lincoln administration’s aims but not to the war itself. However, the very idea of a loyal opposition had been destroyed by the month of blood. At the start of the July session, Stevens already pleaded with his colleagues not to admit the “hissing copper-heads . . . until their clothes are dried, and until they give back the grey uniforms John Breckinridge smuggled into New York and Baltimore. I do not wish to sit side by side with men whose garments smell of the blood of my kindred.” Heeding Stevens’ advice “for perhaps the first time but certainly not the last” as a radical newspaper said gleefully, the Congress expulsed some lawmakers “notorious for their sympathies for treason and butchery”. It never became a complete purge due to Lincoln and the moderates’ objections, but it strengthened the Republican supermajorities and created a mood of prevailing radicalism that helped along in the passage of the Third Confiscation Act.

This coup de main against Chesnut power at the Federal level had its repercussions at the state level too, as the party found itself void of leadership and clear objectives. As the campaign developed, their greatest flaw, their inability to form a coherent message, came to the forefront again, as different factions struggled for power with perhaps more animosity and bitterness than they showed the Republicans. In Ohio, Vallandigham continued his quixotic campaign for governor from his exile in Canada, this despite the attempts of both War Chesnuts and Copperheads to replace him with another candidate. In Pennsylvania, no less than four other candidates threw their hats into the ring, coming from such parties as Constitutional Re-Union, American, Liberty, and Constitutional Union. Alongside Woodward’s still standing National Union candidacy, the result was a grand total of 5 politicos of Democratic origin against the candidate of the united Republican Party.

“Our party is shamefully divided”, despaired a Chesnut voter in Pennsylvania. “The petty struggles of petty men assure our defeat before the tyrant.” But even if petty struggles weren’t enough to assure the Chesnuts’ defeat, several paramilitary groups were ready to take extralegal or even illegal measures to do so. Though they sometimes called themselves Wide-Awakes as a call-back to the 1860 election, the name most commonly claimed by these new clubs was “Union League”. They first appeared in the 1862 elections, where they were little more than Republican debate clubs and printing societies. But as the war radicalized and especially following the Month of Blood, the Union Leagues took a more assertive course. They never became guerrillas or were as brutal as Chesnuts said they were, but they certainly weren’t above using violence or intimidation against the enemies of the government, who were widely seen as just traitors instead of a legitimate opposition.

Similar to how the Confederate guerrillas are the predecessors of the Ku Klux Klan and other terrorist organizations that sought to overturn the new Southern order during Reconstruction, the war-time Union League was the forerunner of several paramilitaries that operated in both North and South with the aim of stamping out disloyalty and defending the gains of the war. Sometimes preserving the Union League name, sometimes changing it to Equal Rights Association or similar, the Southern Union Leagues of Reconstruction were far more radical in methods and objectives, which is explained by the brutality of their foes. Even more moderate political organizations, such as the Union veterans’ Grand Army of the Republic, were profoundly influenced by the Union League, which informed their determination to defend the new order by any means necessary.

The Union Leagues would face terrorist organizations like the Klan during Reconstruction

Several Republican leaders, both during the war and after it, lamented the methods of the Union League. Lincoln himself appealed to their “love for democracy and respect for the Constitution” to try and quiet down overt violence. But Lincoln and other Republican authorities proved unwilling to actually take hard measures against them, because even if their methods were misguided, they agreed with their objectives. The “ghost of old John Brown” seemed to manifest once again, as Republicans took an aptitude similar to the one they had once taken towards that abolitionist warrior: condemning the violence, but lauding it as brave and just. Consequently, even as Republican military and state authorities brought their power to bear against the Sons of Liberty and similar Copperhead associations, the Union League was allowed to guard voting stations, intimidate Chesnut politicians, and even assault particularly outspoken Copperheads. The Republicans, a Chesnut voter wrote in anguish, had “inoculated the general mind with ideas which involve . . . the acquiescence of the community in any measures that may be adopted against the National Union.”

The tacit acceptance of these events by the Lincoln administration came partly from the knowledge of how pivotal the fall elections were. With the process of Reconstruction starting in the Border and the Deep South, and the ink of the radical Third Confiscation Act still fresh, the President and his party wished for a vote of confidence before pressing onward with their objectives. They also believed that such a show of unity and political power was needed to break the Southern spirit and convince the Northern people that they had to fight for unconditional victory. “All the instant questions will be settled by the coming elections,” commented a Lincoln supporter. “If they go for the Rebel party, then Mr. Lincoln will not wind up the war [and] a new feeling and spirit will inspire the South.”

As was customary, Lincoln did not campaign actively, though he and his government took measures to aid the Republican campaigns. In Kentucky, for example, the military authorities, together with the radicals that had taken over the state government following Bragg’s campaign and the Month of Blood, arrested thousands of Chesnut candidates and voters, helping secure the victory of the candidate backed by the administration. Soldiers were furloughed and rushed to Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois and other states to vote the Republican ticket, and Secretary Chase rallied financiers who had made their wealth through government contracts into helping the Republican candidates. While the President could hardly believe that “one genuine American would, or could be induced to, vote for such a man as Vallandigham”, the threat of Copperhead victory was palpable enough for him to overlook the Union League’s actions and aid in these improper, if not illegal, maneuvers.

The clear opposition of the administration and the Union Leagues, and the fatal internal divisions that affected the party, already stacked the odds against the National Union. But even without these factors they would have found it difficult to win the election, for their “tried and true issues” had lost their luster. In vain did Chesnuts try to rally their votes to cries of “let every vote count in favor of the white man, and against the Abolition hordes, who would place negro children in your schools, negro jurors in your jury boxes and negro votes in your ballot boxes!” In the aftermath of Union Mills, and with Black soldiers having also fought gallantly at Liberty and Mine Run, such overt racism seemed unpatriotic. Loyal publication societies and local chapters of the Republican party distributed pamphlets contrasting “the gallant colored soldiers of the Miracle at Manchester” with the “cowardly white traitors of the Massacre at Manhattan”. In a brilliant propaganda coup, a Republican speaker in Pennsylvania campaigned with a Black soldier that had lost his leg at Union Mills, yelling “he gave his leg for your liberty! Won’t you give your ballot for his?” “Campaigning with a Negro”, a Republican voter said in awe, “would have been political suicide a mere year ago . . . these are signs of great change.”

Copperheads were reviled as traitors and supporters of the rebellion.

Other Chesnut issues likewise lost their potency during the 1863 campaign. Speeches against martial law and military tribunals, which had sought to portray them as unnecessary and unconstitutional, now seemed weak and duplicitous when the Month of Blood had proved that Lincoln was right, that there was a fifth column of Confederate sympathizers in the North. Attacks against conscription fell flat, and appeals for peace, now presented as an effort to end the war sooner by offering the already defeated Confederates an opportunity to surrender honorably, were ineffective. Not even the reversals at Dalton and Mine Run were capable of rescuing the Chesnuts from electoral disaster. Divided and attacked, the Chesnuts seemingly gave up towards the end of the campaign season, and the result was an overwhelming Republican triumph.

In Ohio, the Republican candidate won with almost 70% of the votes, while Vallandigham achieved less than 15%, other Chesnut candidates taking the rest. As Secretary Chase happily said, Vallandigham’s defeat was “complete, beyond all hopes”. In Pennsylvania, Governor Curtin was reelected triumphantly with over 60% of the vote, Curtin informing Lincoln that “Pennsylvania stands by you, keeping step with Maine and California to the music of the Union.” And Republicans took supermajorities in the New York legislative elections. Even the Chicago Tribune, a pro-Union journal that was nonetheless highly critical of Lincoln, now called him “the most popular man in the United States” and predicted that if an election were held right then “Old Abe would . . . walk over the course, without a competitor to dispute with him the great prize which his masterly ability, no less than his undoubted patriotism and unimpeachable honesty, have won.”

Republicans and Chesnuts alike interpreted the elections as an endorsement of emancipation and a war for Union and Liberty till complete victory was achieved. “There is little doubt that the voice of a majority would have been against” the Emancipation Proclamation when it was first issued, a Springfield newspaper commented. “And yet not a year has passed before it is approved by an overwhelming majority”. A New York Republican was awed by “the change of opinion on this slavery question . . . is a great and historic fact . . . Who could have predicted . . . this great and blessed revolution? . . . God pardon our blindness of three years ago.” Buoyed by this success, Republicans started to entertain plans for Reconstruction, though the initiative was taken by those in the Border States, specifically, the Marylanders.

Maryland’s unique position as a state with a significant White Unionist element that had been liberated relatively fast by the Federal Army seemed to make it a perfect ground for a “rehearsal for Reconstruction”. However, the state had been devastated by continuous campaigning and several important battles, including Anacostia, Frederick and Union Mills. Fortunately for the Unionists of the state, most of the devastation had been inflicted against the Chesapeake counties that were the base of the slaveholders’ political and economic power in the antebellum. The presence of the Union Army, the mobilization of its sizeable Free Black community, and abolitionist feelings among its white inhabitants contributed to the undoing of slavery as a viable institution in Maryland. By 1863, most Marylanders had concluded that slavery was dead and that new classes of people had to be brought to power, but as in the rest of the South there were sharp disagreements over how slavery was to be liquidated and what role, if any, Black people were to play in the new order.

Maryland’s transformation was punctuated by the help of many Northern politicians and activists that came to the state as “heralds of Yankee culture” that sought to aid it in its transition to free labor. Reformers of an idealistic stripe known as the “Gideonites”, these emissaries brought with them new ideas and a genuine desire to uplift the freedmen and help along in their education and progress. They were most influential in the South Carolina sea islands, where an experiment in black land ownership was being conducted, though their power, both there and in Maryland, was limited when compared with Treasury officials and army officers. Nonetheless, the Gideonites gathered great publicity around their efforts, which helped promote the redistribution of land to the former slaves and encourage the growth of a Republican Party in Maryland.

Andrew Curtin

Leading the Maryland radicals was Henry Winter Davis, a representative that bitterly opposed Lincoln because the President had sustained his enemies in the Blair clan, though Davis was somewhat mollified when the Blairs broke with the administration in the aftermath of the Emancipation Proclamation. When a Constitutional Convention was called early in 1863 after the victory at Anacostia seemed to secure the state once and for all, Radicals swept to power, partly aided by the memory of the recent campaign, partly by loyalty oaths administered by the military. The main concern of the Convention was abolition, and, although some conservative Unionists insisted on compensated emancipation, Davis and his men stood firm, declaring that “their compensation is the cleared lands of all Southern Maryland, where every thing that smiles and blossoms is the work of the negro that they tore from Africa.” Immediate, uncompensated emancipation was enacted.

Aside from abolition, the Convention took several progressive steps, aimed at breaking the power of the old planter aristocracy and install in Maryland a system of free labor. Public education was established for the first time, along with progressive taxation and protections against seizure for debt to benefit poor yeomen. But the big question of the era was what was to be done with the enslaved, now freedmen. Though some delegated disclaimed “any sympathy with negro equality”, Davis and his radicals moved to incorporate at least some form of Black suffrage within the state constitution, which arose “such terrible cries” from the conservatives that it had to be removed lest the whole Unionist party collapse.

As the Convention closed with cheers for the “new and regenerated Maryland”, a disgusted Radical declared that none of its work had “been from high principle, … but party spirit, vengeful feeling against disloyal slaveholders, and regard for material interest. There has been no expression, at least in this community, of regard for the negro—for human rights. But even as they were defeated, the radicals could see some glimmers of hope, in that the Convention had decreed equal access to the courts and the law system and abolished the apprenticeship system that bound black minors to white adults, without the consent of their parents, as a half-way to preserve slavery. “We were defeated in the battle for political equality”, Davis admitted gloomily, “but the right triumphed in the battle for civil equality. There is still hope that we may carry this issue to victory in the next great struggle.”

The next battle came sooner than Davis and the radicals could have expected or hoped. Two events aided in this development. First, the rebel victory at Bull Run and the expectative that they could invade Maryland resuscitated pro-Confederate sentiments in Maryland and led the new constitution to defeat. This despite the efforts of the Convention to prevent the disloyal from voting by requiring loyalty oaths and disenfranchising those who had expressed even a mere “desire” for the Confederacy to triumph. But just a month afterwards, the Confederates invaded. The attempt of some Annapolis delegates, some of whom had served as conservative members of the Convention, to throw their lot in with the Confederacy, and the gory riots in Baltimore discredited the conservative Unionists, and, as in the North, made all Republicans identify opposition to their goals as opposition to the war and thus treason. As the dust settled in a Baltimore covered in blood and news arrived of the USCT’s decisive role in Union Mills, Marylanders recognized that a new era had dawned in Maryland.

A second Convention was called, and the Radical victory was even more overwhelming this time. Conservative attempts to portray this effort as one in favor of “free-loveism, communism, agrarianism” failed, and when the Convention assembled the first item in the agenda was not abolition, but black suffrage. Though some Unionist still hoped that they could hold into power through disenfranchisement, and new such measures were indeed enacted, conversation shifted towards giving the franchise to Black Marylanders, who represented 20% of the state’s population. However, even in the aftermath of Union Mills there were many who were not ready for such a momentous step. Acrimonious debate followed, punctuated by racist appeals on one side and politically-motivated praise for the USCT on the other.

At the end, the radicals only managed to achieve limited Black suffrage, for veterans of the Union Army and the literate. But even this limited victory was a great triumph, for, as one delegate admitted “no sane, sober man could have ever predicted that a Southern state would ever give the suffrage to the Negro.” Furthermore, Maryland had furnished a large number of Black soldiers to the Union Army, up to 50% of the eligible Black males, and literacy was higher among its free Black population than in other African American communities. Coupled with this provision was a change in the basis of representation, which would only count voters instead of the entire population – which weakened the plantation counties and made it so that disenfranchisement would only weaken them even more.

The Maryland Constitutional Convention was profoundly influential as a "blueprint" for Reconstruction

Despite widespread disenfranchisement, the new constitution was not sure to pass, because many loyal voters were opposed to “nigger government.” But the ballot was not their only weapon. Armed groups of whites attacked the polling stations where veteran soldiers were casting their first votes, murdering several. Veterans of Union Mills, “the gallant braves who saved our state from rebel rule”, were among those slain. White Unionists were also intimidated, and in a preview of things to come a group of pro-Confederate men started a riot in Frederick that had to be gorily put down by the Federal Army. But this attempt to prevent the Reconstruction of Maryland only resulted in a stronger commitment to its realization on the part of the Union authorities. Lincoln thus suspended the writ of habeas corpus, decreed that those found under arms should be tried as guerrillas, and allowed several Union Leagues to pay the rebels with the same coin. The result was that many people sympathetic to the Confederacy, or suspected of being so, were intimidated or even murdered. Unionists accepted this, saying that “even the most worthless negro is more deserving than a reb", of both the ballot and life itself.

The new constitution was thus approved early in 1864, aided by new disenfranchising provisions and the campaign of intimidation led by the Union Army, and the Union Leagues, by then basically the paramilitaries of the Republican Party. Black veterans, despite hurdles and danger, came out and voted in great numbers, a fact that, a conservative delegate said, “had raised the spirit of old Roger Taney and made his howls heard all over the land.” At the end, the controversial constitution passed by a mere 589 votes, a victory owed to the Black voters who had so enthusiastically endorsed it. But it was also owed to violent repression, leading to never-ending debates over the legitimacy of the referendum and whether the ends justified the noble means. For Republicans, the answer was an unambiguous yes. Nonetheless, the fact that even after employing all these methods the victory was a close one underscored the inherent weakness of the new Republican regime and the resistance of White Southerners to these astounding changes. But these apprehensions were lost among the chorus of jubilant celebrations. Lincoln himself extended his congratulations to “Maryland, and the nation, and the world, upon the event”, and said that “it gratifies me that those who have served gallantly in our ranks are free to vote”.

The Maryland Constitution also had an effect in the rest of the Border South, inspiring the Republicans in those states to take more Radical measures. Their success was limited in Delaware and Kentucky, where old elites retained their grip in power and there were few radical leaders or great events to push them towards change. By contrast, Missouri went in some ways farther than Maryland had done. There, the bloody civil war that raged along the border with Kansas and a large population of abolitionist German immigrants resulted in a particularly strong Republican Party that was greatly embittered against the rebels. What Lincoln called a “pestilent factional quarrel” had divided the state’s Unionists and prevented the enactment of changes, creating two factions, the radical “Charcoals” and the moderate “Claybanks”. Though he sympathized with the Claybanks, Lincoln could not tolerate their willingness to ally with former Confederates in the pursue of political power, and the President would end up backing the radicals because, although they were “the unhandiest devils in the world to deal with”, they were “absolutely uncorrosive by the virus of secession” and had “their faces set Zionwards.”

The President’s support for the Radicals was increased by his break with the Blair clan, which remained influential in Missouri. Still, Lincoln was unwilling to back radical measures, warning that a slave state was like a man with “an excrescence on the back of his neck, the removal of which, in one operation, would result in the death of the patient, while ‘tinkering it off by degrees’ would preserve life.” Helped along by the radical General Curtis, the state’s Unionist, including such leaders as Charles Drake and B. Gratz Brown, started a virtual revolution. When a state Constitutional Convention finally met in middle 1864, it enacted immediate, uncompensated emancipation, mandated black civil equality, and coupled limited Black suffrage with widespread disenfranchisement of former Confederates. At its most extreme, Missouri required loyalty oaths even for teachers, lawyers and ministers and enacted a confiscation plan to redistribute land to the freedmen – a disposition made even more radical by the fact that Black landowners could vote even if illiterate.