I also wonder if the apparent success of monarchical Colombia wouldn't eventually lead to revisionism about Hamilton in the US, where his monarchism would be seen to have been vindicated by history

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

If You Can Keep It: A Revolutionary Timeline

- Thread starter Fed

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 33 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter XXIV - "My Crown for the Paraná". The Election of 1838 Chapter XXV - En un coche de agua negra.... Chapter XXVI - ... Iré a Santiago. Chapter XXVI.5 - Blackness in Colombia Chapter XXVII - No Continent for Enslaved Men Chapter XXVIII - Francia, Domestic Edition Chapter XXIX - The Last Emperor Chapter XXX - The Mandate Shifts - Southern China in the Qing Collapse.I also wonder if the apparent success of monarchical Colombia wouldn't eventually lead to revisionism about Hamilton in the US, where his monarchism would be seen to have been vindicated by history

That’s a really good point, but throughout the years in the American system Hamilton will take on the role of Benedict Arnold as the “OG traitor”, because since he was an immigrant, kind of monarchist and followed a route of liberalism very similar to that of the Creoles, he’ll be seen as a Colombian in disguise. This and the fact that he essentially led a coup d’état by occupying Virginia will make him a really vilified figure in most of the country - though of course he’ll have his proponents.

Chapter V - The End of Hamilton's Folly

The South is a lost cause

From Volkspedia, the people’s encyclopedia

“The South is a lost cause” was a remark made by Josiah Harmar, at the time the chief officer of federal occupying forces in Virginia, after the start of the First American Civil War, perceiving the dismal public approval of the federal armies in Virginia and the lack of any support from Southern States towards Alexander Hamilton’s federal government. The phrase has since become a popular part of the political lexicon by Northerners attempting to disparage the South.

Context

The First American Civil War started in full force after talks between Hamilton and Jefferson’s rival governments broke down. In March of 1801, a militia that had been personally formed by Thomas Jefferson in the town of Lynchburg fired at the American military garrisoning the town (which was under occupation since the Nullification Crisis of 1799, and the subsequent United States presidential election, 1800. The Nullification Crisis had been mostly supported by Southern states concerned at Alexander Hamilton’s perceived abolitionism and overreach of federal power, and soon enough many militias had broken out throughout Southern states, effectively destroying federal power on the local scale.

The Union army that remained within Virginia in particular (and in the South in general) was low on morale, on a less than favorable political position to continue their occupation, and, in certain towns, even outgunned by local militias, and soon began to withdraw from tactical locations in the South, eventually vacating Virginia by march of 1800. This withdrawal was not authorized by the Commander in Chief Alexander Hamilton, which led Josiah Harmar to write in a letter to Hamilton:

“The Union has no support here… the Southrons have all been convinced by Madison’s rhetoric, and not even Washington could convince them to lay down their arms by Peace. It was a difficult decision, sir, but to hold the garrisons in the South you’d need the entirety of the Union Army. Without a more cohesive campaign, the South is a lost cause”.

The Handshake to End the War, which was the opening salvo of negotiations between Jefferson and Hamilton, ocurred outside a Quaker church in Dover, Delaware.

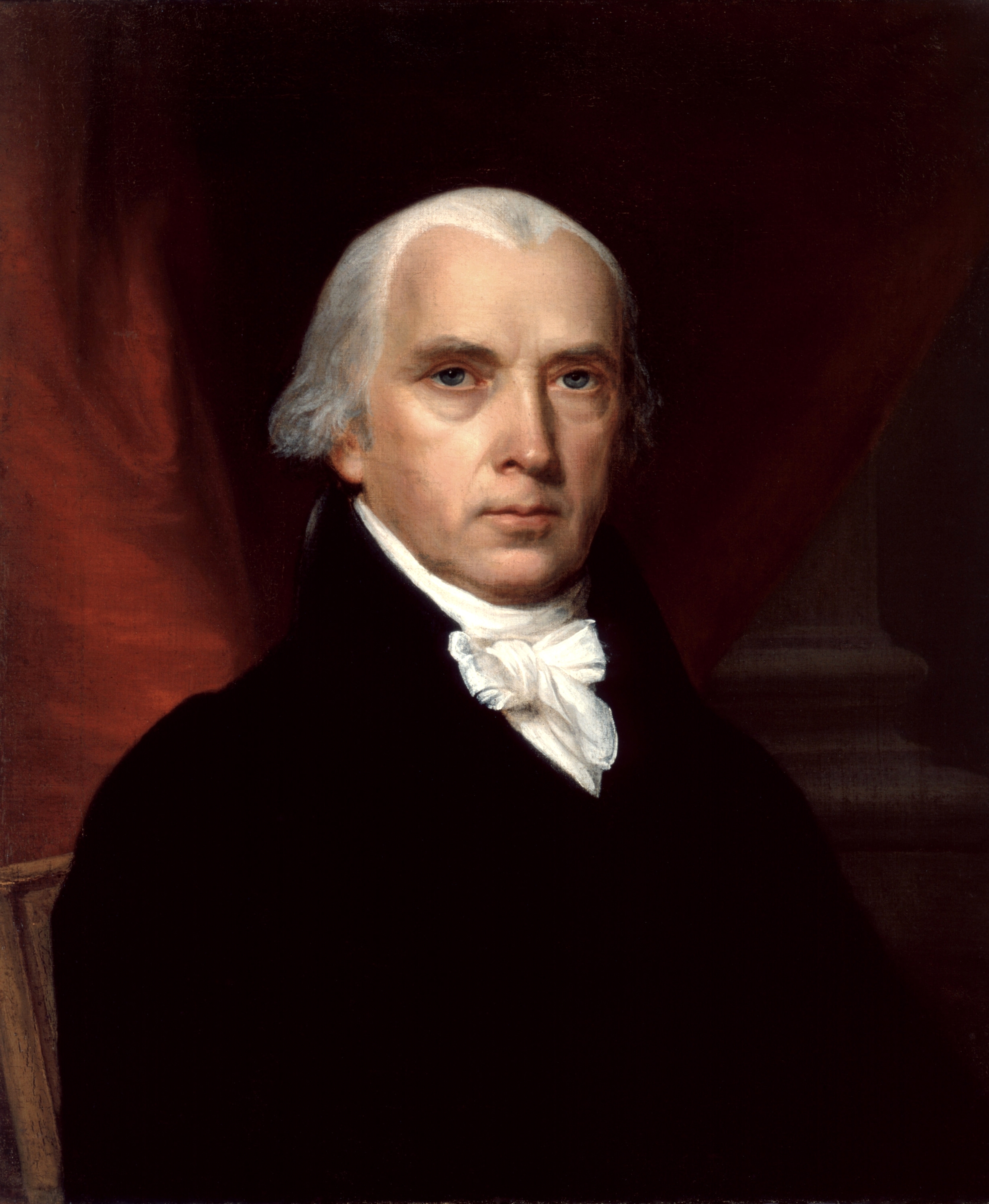

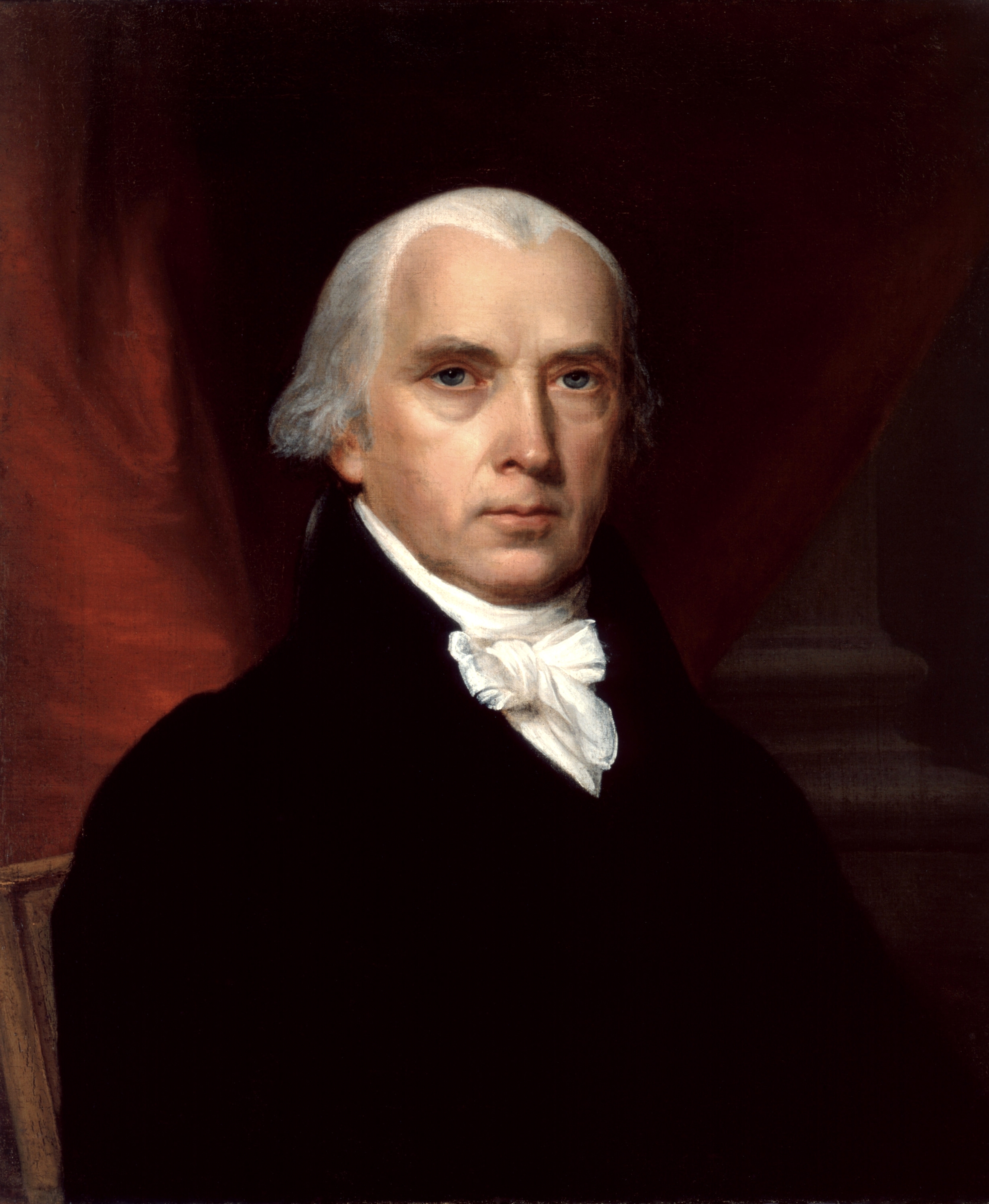

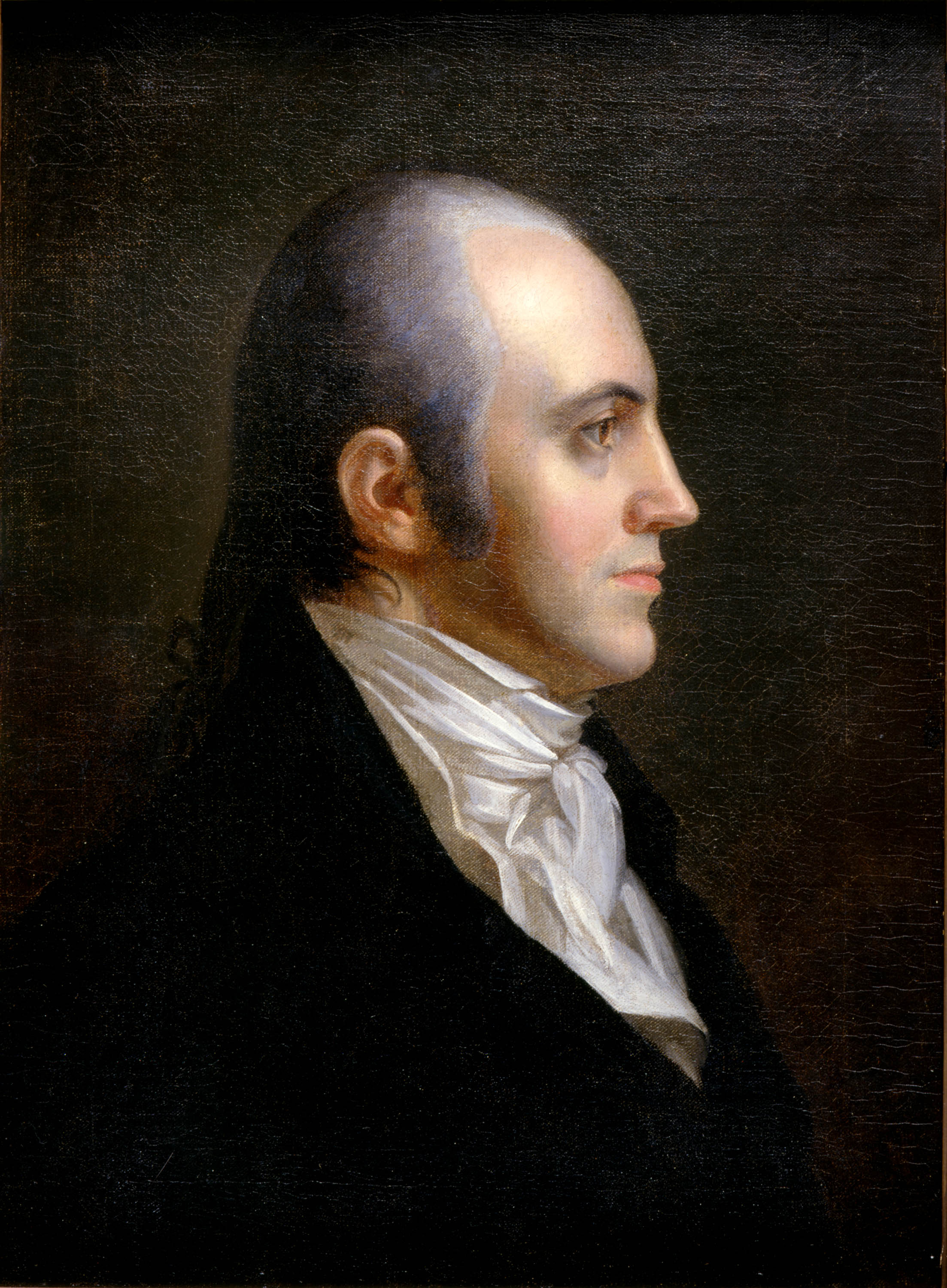

Despite his wide recognition as perhaps the most important Founding Father besides Washington during the period of independence, Thomas Jefferson (left)'s political star was crushed after Hamilton's Folly. Despite not being as widely blamed for the conflict as Hamilton was, his image was tarnished. Soon, the collapse of the Democratic-Republican Party and the rise of Madisonite (centre) and Burrite (right) factions would knock him out of the political arena.

“1803 saw the continuation of a grueling war that devastated the Virginian countryside and killed hundreds, and then thousands, of Americans. In 1802, Madison had condemned the war as one that had ‘put brother against brother’ and started reaching out to other pacifists in the Union government, especially led by Aaron Burr and other factions of Northern Democratic-Republicans. Eventually, the war got to a point where even Hamilton’s and Jefferson’s anger and political differences were minor in comparison to the attrition that the war was causing. Jefferson and Hamilton, under mediation by Burr and Madison, met in Dover, Delaware, to negotiate what today is known as the Compromise of 1803. The Compromise seeked to end Hamilton’s rule and address many of the issues that Southern states saw as a threat, while at the same time maintaining Hamilton’s legacy. The final points to the Compromise saw just this, with the Jeffersonians gaining several things, including:

On the other hand, Hamilton and his Federalists retained several different of their institutions from the Adams and Hamilton presidency, including:

The end of the Nullification War brought upon the brief Jefferson Presidency, which was mostly concentrated in recovering order after a three-year war and bringing prosperity back to Virginia and Maryland, the two States most badly affected by the war. The entirety of Jefferson’s year-long tenure was focused on one single State: Virginia, and the reconstruction efforts, as well as the expansion of negotiation with foreign powers. As an afterthought, however, Jefferson commissioned an expedition to survey the territories of Louisiana north of the River Platte, to see what the country had acquired. Starting off in Saint Charles (the new capital of Wabash Territory, on the other side of the Missouri River from San Luis), Merriwether Lewis and William Clark surveyed most of the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains, changing American topography.

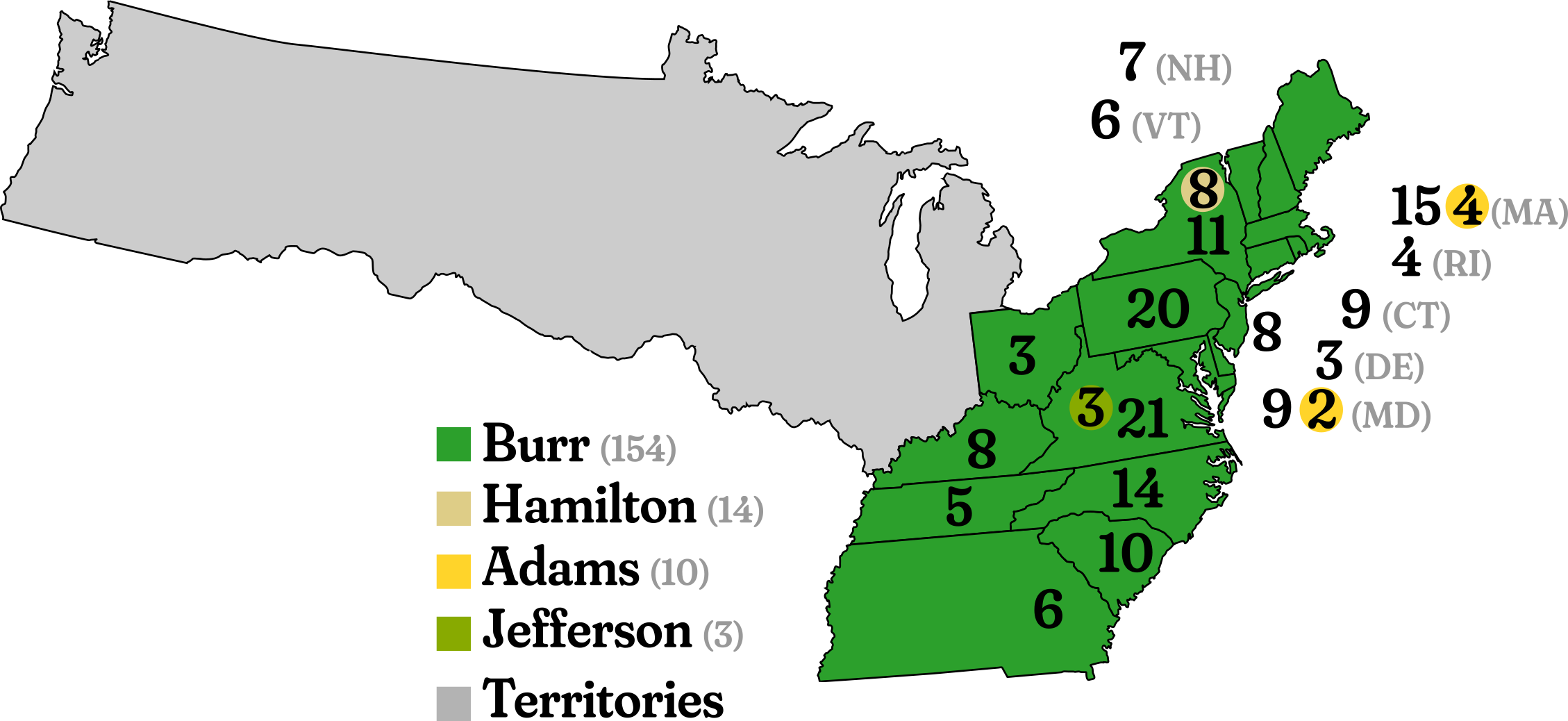

The election of 1804 saw a unified attempt by the Federalist Party and the Republicans to elect Burr and Madison on a “compromise” platform. Burr got 154 out of 176 electoral votes; Madison got 157. The other 17 electoral votes went to John Adams, Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson. Smooth transition of power, despite the chaotic period that preceded it, was assured.

The Election of 1804 was a sweeping victory for the "compromise" (truly, Democratic-Republican) ticket of Burr and Madison.

-Excerpt from “Nullification as a Constitutional Procedure in the Early United States” by David Johnson. Published by Harvard University, 1988.

The Compromise of 1804 is mostly seen, in American historiography, as fundamental because of the end of Hamilton's Folly. However, equally important was the more-or-less modern determination of North American borders between Spain (eventually Colombia) and the United States. Despite being seen as a relative defeat for the United States for many American nationalists, the Treaty of New Orleans of 1804 was the largest ever territorial expansion done by the United States in a single treaty, granting the country territory occupied by ten States today.

"Continental jurisprudence, and its doctrine, have long been influenced by the decisions of the Colombian Federal Imperial Court and the State Council, especially their principles of State indemnity and responsibility, the existance of a figure of eminent domain requiring compensation, the damages recognised during periods of conflict to civilians, done both by State actors as well as by rebels, and the eventual creation of an Administrative Jurisdiction that deals with the many and complex figures that result from action by the Administration. Of course, all of the thinking of Colombian jurisprudence is eminently continental in its thought, descendant from Spanish and Roman law as it is, and therefore far more applicable to the systems of Europe and Africa than any other similar figure of historical jurisprudence.

This paper's role is not to discuss the evident and immense importance of Colombian legal thought in the development of the modern figure of the State, and the judiciary's involvement in maintaining the State within the bounds of judicial review and the public interest. However, the idealisation of Colombian jurisprudence by some scholars has prevented the understanding of another important source of jurisprudence; the American Supreme Court, especially that previous to the Period of National Reorganization, which, in many cases, preceded by several decades the same decisions the Federal Imperial Court would eventually take.

This is not only seen in the figure of State Nullification (a uniquely American figure, and one only replicated in a few other states), the most commonly discussed result of the end of the First American Civil War, but also through the figure of judicial review, which was fundamental to the development of an independent judiciary and was first seen through the Hamilton v. Jefferson case of 1805, dealing with judicial appointments.

As a way to ensure the entirety of his legacy would not be overturned by the following Democratic administrations, the outgoing Hamilton government, only hours before the Peace of Dover came into effect, decided to appoint several critical supporters to the new Wabash Judiciary as well as several other district courts, named "the midnight judges". With one of the goals of the Democratic-Republican Party in Wabash being the styming of any action by the new Hamiltonian government through control of Jeffersonians in the Court system, this was seen as a strong breach of the peace agreement by Hamilton, and tried to stop these decisions. This act was seen as illegal by the Hamiltonian State government, who sued Jefferson in the Supreme Court. The resulting ruling, written by justice William Cushing, was a fundamental element of American constitutional law, and a second blow to the American Federal Government; now, not only could the State governments could nullify their laws under certain cases, but the Supreme Court also attributed itself the role of judicial guardian of the Constitution, stating that: Congress cannot pass laws that are contrary to the Constitution, and it is the role of the judiciary to interpret what the Constitution permits.

Though not as important for the Continental jurisprudence system as similar Colombian rulings such as the Conventos de Popayán ruling of 1828 or the Santander v. The Congress ruling of 1848, it is still of paramount importance to recognise Hamilton v. Jefferson as the true birth of judicial review of laws in a modern sense. After all, it is entirely possible that later Colombian rulings inspired themselves on the Supreme Court; after all, in 1804, the Colombian elite's attitude towards the United States was still one of awe and admiration, and hadn't declined as greatly as it later would."

-The Forgotten Gem of Judicial Review. Published in the St.John's University Law Review, Saint John's University Department of Legal Studies, Newfoundland, United Kingdom, 1987.

From Volkspedia, the people’s encyclopedia

“The South is a lost cause” was a remark made by Josiah Harmar, at the time the chief officer of federal occupying forces in Virginia, after the start of the First American Civil War, perceiving the dismal public approval of the federal armies in Virginia and the lack of any support from Southern States towards Alexander Hamilton’s federal government. The phrase has since become a popular part of the political lexicon by Northerners attempting to disparage the South.

Context

The First American Civil War started in full force after talks between Hamilton and Jefferson’s rival governments broke down. In March of 1801, a militia that had been personally formed by Thomas Jefferson in the town of Lynchburg fired at the American military garrisoning the town (which was under occupation since the Nullification Crisis of 1799, and the subsequent United States presidential election, 1800. The Nullification Crisis had been mostly supported by Southern states concerned at Alexander Hamilton’s perceived abolitionism and overreach of federal power, and soon enough many militias had broken out throughout Southern states, effectively destroying federal power on the local scale.

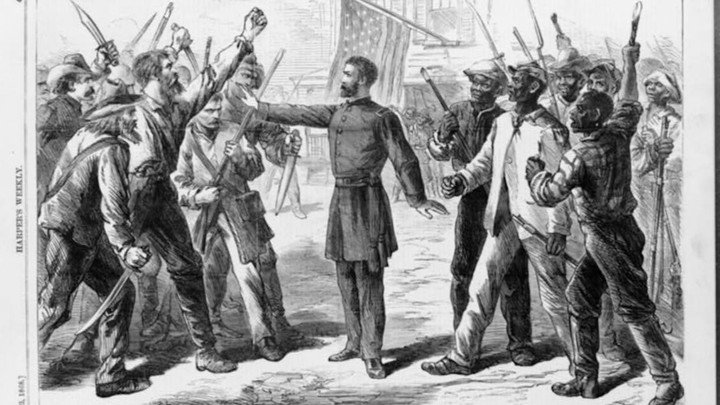

Vandals on the Potomac, a 1827 painting of unkown (but probably pro-Hamiltonian) attribution,

details one of the Jeffersonian militias.

details one of the Jeffersonian militias.

The Union army that remained within Virginia in particular (and in the South in general) was low on morale, on a less than favorable political position to continue their occupation, and, in certain towns, even outgunned by local militias, and soon began to withdraw from tactical locations in the South, eventually vacating Virginia by march of 1800. This withdrawal was not authorized by the Commander in Chief Alexander Hamilton, which led Josiah Harmar to write in a letter to Hamilton:

“The Union has no support here… the Southrons have all been convinced by Madison’s rhetoric, and not even Washington could convince them to lay down their arms by Peace. It was a difficult decision, sir, but to hold the garrisons in the South you’d need the entirety of the Union Army. Without a more cohesive campaign, the South is a lost cause”.

The Handshake to End the War, which was the opening salvo of negotiations between Jefferson and Hamilton, ocurred outside a Quaker church in Dover, Delaware.

Despite his wide recognition as perhaps the most important Founding Father besides Washington during the period of independence, Thomas Jefferson (left)'s political star was crushed after Hamilton's Folly. Despite not being as widely blamed for the conflict as Hamilton was, his image was tarnished. Soon, the collapse of the Democratic-Republican Party and the rise of Madisonite (centre) and Burrite (right) factions would knock him out of the political arena.

“1803 saw the continuation of a grueling war that devastated the Virginian countryside and killed hundreds, and then thousands, of Americans. In 1802, Madison had condemned the war as one that had ‘put brother against brother’ and started reaching out to other pacifists in the Union government, especially led by Aaron Burr and other factions of Northern Democratic-Republicans. Eventually, the war got to a point where even Hamilton’s and Jefferson’s anger and political differences were minor in comparison to the attrition that the war was causing. Jefferson and Hamilton, under mediation by Burr and Madison, met in Dover, Delaware, to negotiate what today is known as the Compromise of 1803. The Compromise seeked to end Hamilton’s rule and address many of the issues that Southern states saw as a threat, while at the same time maintaining Hamilton’s legacy. The final points to the Compromise saw just this, with the Jeffersonians gaining several things, including:

- The resignation of Alexander Hamilton from the Presidency, with Vice-President Elect Thomas Jefferson taking over charge until 1804,

- The recognition of State Nullification as a legitimate constitutional check and balance on the Federal government by part of the States,

- The enshrining of slavery in Southern states in the United States Constitution via the Twelfth Amendment, which recognised slavery as legal in “all States that decide to enshrine the practice”, as well as a promise not to revisit the issue of slavery or slave trade until 1825,

- A promise by leaders of the Congress Federalist Party to lower federal tariffs and abstain from putting new ones in place until 1810,

- The signing of a peace treaty with France which ended the War of 1798 - a peace treaty that, due to Napoleon’s European concerns, gave away all of Louisiana north of the Platte river as well as most (but not all) of Spain’s claims to the Oregon Country to the United States, while recognizing Louisiana as part of Spain.

On the other hand, Hamilton and his Federalists retained several different of their institutions from the Adams and Hamilton presidency, including:

- The Federal government being able to selectively set tariffs over the states, with trade issues, recognised as Federal jurisdiction under the Tenth Amendment, being exempt from State Nullification,

- The agreement by part of Republicans to maintain the scope and powers of the National Bank as they were instated by Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasury, as well as Hamilton’s less controversial proposal for a national mint,

- The capital of the United States remaining in Philadelphia, instead of a more southern location along the Potomac (as Madison suggested),

- The recognition of Hamilton as the governor of Wabash Territory, a new territory taken from Indiana’s southern half, which could permit the establishment of a more purely Federalist “laboratory of democracy”, and

- The assurance that, after stepping down from the Presidency in 1804, Jefferson would not seek re-election.

The end of the Nullification War brought upon the brief Jefferson Presidency, which was mostly concentrated in recovering order after a three-year war and bringing prosperity back to Virginia and Maryland, the two States most badly affected by the war. The entirety of Jefferson’s year-long tenure was focused on one single State: Virginia, and the reconstruction efforts, as well as the expansion of negotiation with foreign powers. As an afterthought, however, Jefferson commissioned an expedition to survey the territories of Louisiana north of the River Platte, to see what the country had acquired. Starting off in Saint Charles (the new capital of Wabash Territory, on the other side of the Missouri River from San Luis), Merriwether Lewis and William Clark surveyed most of the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains, changing American topography.

The election of 1804 saw a unified attempt by the Federalist Party and the Republicans to elect Burr and Madison on a “compromise” platform. Burr got 154 out of 176 electoral votes; Madison got 157. The other 17 electoral votes went to John Adams, Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson. Smooth transition of power, despite the chaotic period that preceded it, was assured.

The Election of 1804 was a sweeping victory for the "compromise" (truly, Democratic-Republican) ticket of Burr and Madison.

-Excerpt from “Nullification as a Constitutional Procedure in the Early United States” by David Johnson. Published by Harvard University, 1988.

The Compromise of 1804 is mostly seen, in American historiography, as fundamental because of the end of Hamilton's Folly. However, equally important was the more-or-less modern determination of North American borders between Spain (eventually Colombia) and the United States. Despite being seen as a relative defeat for the United States for many American nationalists, the Treaty of New Orleans of 1804 was the largest ever territorial expansion done by the United States in a single treaty, granting the country territory occupied by ten States today.

This paper's role is not to discuss the evident and immense importance of Colombian legal thought in the development of the modern figure of the State, and the judiciary's involvement in maintaining the State within the bounds of judicial review and the public interest. However, the idealisation of Colombian jurisprudence by some scholars has prevented the understanding of another important source of jurisprudence; the American Supreme Court, especially that previous to the Period of National Reorganization, which, in many cases, preceded by several decades the same decisions the Federal Imperial Court would eventually take.

This is not only seen in the figure of State Nullification (a uniquely American figure, and one only replicated in a few other states), the most commonly discussed result of the end of the First American Civil War, but also through the figure of judicial review, which was fundamental to the development of an independent judiciary and was first seen through the Hamilton v. Jefferson case of 1805, dealing with judicial appointments.

As a way to ensure the entirety of his legacy would not be overturned by the following Democratic administrations, the outgoing Hamilton government, only hours before the Peace of Dover came into effect, decided to appoint several critical supporters to the new Wabash Judiciary as well as several other district courts, named "the midnight judges". With one of the goals of the Democratic-Republican Party in Wabash being the styming of any action by the new Hamiltonian government through control of Jeffersonians in the Court system, this was seen as a strong breach of the peace agreement by Hamilton, and tried to stop these decisions. This act was seen as illegal by the Hamiltonian State government, who sued Jefferson in the Supreme Court. The resulting ruling, written by justice William Cushing, was a fundamental element of American constitutional law, and a second blow to the American Federal Government; now, not only could the State governments could nullify their laws under certain cases, but the Supreme Court also attributed itself the role of judicial guardian of the Constitution, stating that: Congress cannot pass laws that are contrary to the Constitution, and it is the role of the judiciary to interpret what the Constitution permits.

Though not as important for the Continental jurisprudence system as similar Colombian rulings such as the Conventos de Popayán ruling of 1828 or the Santander v. The Congress ruling of 1848, it is still of paramount importance to recognise Hamilton v. Jefferson as the true birth of judicial review of laws in a modern sense. After all, it is entirely possible that later Colombian rulings inspired themselves on the Supreme Court; after all, in 1804, the Colombian elite's attitude towards the United States was still one of awe and admiration, and hadn't declined as greatly as it later would."

-The Forgotten Gem of Judicial Review. Published in the St.John's University Law Review, Saint John's University Department of Legal Studies, Newfoundland, United Kingdom, 1987.

Last edited:

Chapter VI - The Age of Burr

Elected to the Presidency on a compromise platform, Burr, the "Sulla of America", would loom large over the ensuing years.

“Burr was politically astute enough to realise that the overwhelming majority of his political platform, which was incredibly radical for its time, would not pass. He did, however start speaking in favour of some of the issues at hand. Soon enough, Burr started spreading the soapbox for increasingly egalitarian ideas, some too extremist to be even considered in revolutionary hotbeds like France. Slowly but surely, within his first year Burr alienated the entirety of the United States political system, clearly creating a third political position strongly separate from Jeffersonian Republicans and Hamiltonian Federalists.

Burr’s first issues with the political establishment came when he started supporting debt relief for farmers, something that had been proposed by the Republicans and was going to be signed into law. However, soon Burr made shockwaves by saying that, while the law proposed was welcome, it didn’t go nearly far enough. He proposed the expansion of debt (and its eventual possible relief) to the entirety of American citizens, something that Federalists balked at. The expansion of the financial plan to include all members of society became a nightmare straight out of “an egalitarian enragé’s twisted mind” (as Hamilton especially tarred Burr from his paper in Saint-Charles). His proposal in front of congress to repeal the Sedition Act eventually completely turned all Federalist party members away from him. The Compromise of 1804’s conciliatory nature lay in tatters within seven months.

Of course, soon enough Democratic-Republicans would join the Federalists in outrage at Burr. Southern states were horrified to realise that they had overthrown Hamilton, who they perceived as a moderate abolitionist who would not permit the continuation of the spread of slavery, and replaced him with Burr, who was an outspoken abolitionist (despite having been a slaveowner) who wanted to end slavery outright. While Burr never did attempt to coerce his allies into removing slavery (it would fly in the face of the newly-implemented Constitutional amendment), he did speak often against it, leading to abolitionist rhetoric spreading out of Philadelphia into New York City. He disgusted Jefferson by praising the Supreme Court’s decision to forbid Republican judicial appointments, instead maintaining Hamilton’s and declaring some of Jefferson’s two-year presidency’s laws unconstitutional.

And of course, every “enlightened” American balked at his most crazy proposal: the back then unthinkable assessment that women were the intellectual equals to men. Burr’s support of women’s suffrage came both as a surprise and as a slap in the face to patriarchal society, and soon became the most unpopular of his proposals, he being slammed by his “insane hermaphroditical wish for women to run the country” in every paper in the United States. Barely into 1806, correspondence between Madison and Jefferson made their intent clear: the man had to go.”

-Carlotta Nussbaum, “Burr The Progressive”. Publichsed in the New York University Faculty of Political Science, 2007.

“Jefferson decided against trying to start an impeachment trial or another more violent method to expel Burr from the presidency. After all, he had written both the Constitution and the Compromise of 1804; it would have been absurd to fly directly in the face of both by breaking all procedure and supporting an impeachment when the main issue was political disagreement. Instead, Jefferson decided to pull all the strings in the Democratic-Republican Party to make sure that Burr’s very scant allies in Congress would be unable to pass any laws supporting his Administration.

Burr realised this soon enough, and started doing the unthinkable; he returned the favor the Republicans did to him in Congress, and started vetoing through political motives. For the Americans at this point, this was absurd; previous Presidents had only vetoed with the issue of possible unconstitutionality. Not even Hamilton had gone as far as Burr in restricting legislative power.

But the stalemate soon survived, with Congress not wanting to overthrow Burr violently. Instead, they waited until the Election of 1808, in which the ticket was supposed to be re-elected; only this time, a fully Republican ticket of Madison and George Clinton was elected by the Electoral College. Burr got only New Jersey's 8 votes and two electors from North Carolina, actually coming in third to the Federalists' Charles Pickney.

Burr left the White House promising revenge, and indeed, revenge he would have soon. While he was not popular amongst the Southern elites, his plans for debt relief had granted him ample popularity within New York and certain parts of the North. Many amongst New York’s high society were now urging him to turn the tables on Jeffersonian Republicans and repeat what they had done six years later: run for the governorship of New York, and, with support in the Legislature amongst a new egalitarian movement and the Federalists, nullify the Federal government’s actions.

Burr decided against this idea. Instead, he marched. After convincing about 3,000 poor New Yorkers that his expulsion from the Presidency meant that the Federal government was looking to end his proposals at an agrarian bank and water services, he began moving west. Eventually, Burr managed an army of nearly 10,000 armed peasants, poor city dwellers and freed slaves to move West with him.”

-Johnson, Charles. “Burr’s War and the Rise of the Democratic Party”. Published by Saint James Editorials, Tecumseh, Indiana, in January 15 of 2007

Results of the election of 1808

Last edited:

Wait, Burr was run on the Federalist ticket? How did he win New Jersey? Why did the Federalists nominate such a radical?

Wait, Burr was run on the Federalist ticket? How did he win New Jersey? Why did the Federalists nominate such a radical?

No, Aaron Burr ran as an independent (Historians would later call him a "Burrite", as the precursor to the Democratic Party, as we'll see in a bit). I figured New Jersey was the best state for him to win since New Jersey was on its own Federalist to Democratic-Republican swing iOTL, as well as having recently abolished slavery, so maybe Burr's abolitionist rhetoric would bode well with New Jeresey politicians. The Federalists instead nominated Charles C. Pickney, who won Hamilton's state of Wabash as well as a few electors in his home state, in Kentucky and in New York.

Ah. Maybe change the burrite color? It being the Federalist orange is confusing. You could switch colors with the federalists.No, Aaron Burr ran as an independent (Historians would later call him a "Burrite", as the precursor to the Democratic Party, as we'll see in a bit). I figured New Jersey was the best state for him to win since New Jersey was on its own Federalist to Democratic-Republican swing iOTL, as well as having recently abolished slavery, so maybe Burr's abolitionist rhetoric would bode well with New Jeresey politicians. The Federalists instead nominated Charles C. Pickney, who won Hamilton's state of Wabash as well as a few electors in his home state, in Kentucky and in New York.

Chapter VII - The Birth of Wabash and the Effects of Burrism

"Join, oh, our dance!

The dance of those left-over.

No-one will notice our prance.

Nobody helped; their capital has no spillover"

The dance of those left-over.

No-one will notice our prance.

Nobody helped; their capital has no spillover"

-The Dance of the Left-Over, by the Massachussetts musical group The Prisoners. Despite The Prisoners having a clear Marxist ideology, the song has become an anthem to modern Burrites.

"The political ideology that today has come to be known as Burrism has little, if anything, to do with the original proposals of Aaron Burr, the American president between 1804 and 1808. Despite the fact that Burr was radically progressive at the time of his Presidency, which was what directly led to the American political establishment turning against him and the beginning of Burr's War, the messages that Burr proposed would be considered basic by any modern American progressive; a State-sponsored Central Bank, the granting of financial aid to small labourers and farmers and racial and ethnic equality are, today, the law of the land throughout the American Continent, at least in theory. No, the truly wonderful part of Burrism, what has caught the eye of so many American populists seeking to combat the fire of European-style socialism with their own systems, is its spirit. A wonderfully inclusive, heterogeneous, and diverse spirit, the ideology of Burr has been invoked by many strongmen throughout the years, from the far right to the far-left.

However, the inclusiveness of Burrism, of the Great Ragtag Armies of 1808 and 1809, is largely a historical myth. Despite what modern Burrites would let you believe, Aaron Burr's forces were not some radically inclusive system which included every race and every religion in glorious harmony. Instead, the regiments of the Ragtag Armies were almost entirely segregated; a necessity, in times where the interaction between whites and free Blacks, or whites and Natives, would be enough to trigger a race riot. Instead, armies marched far apart from each other, expecting not to find other armies, and very vaguely being led by Burrite elements, instead being loosely patched together through personal fealty to Burr himself (in the case of Eastern forces) or to his allies (in the case of those in Indiana and the Mississippi River Basin).

The nature of Burrism and the segregated armies explains several things. First of all, the nature of the State of Indiana, which, despite its claims of being the "most diverse State in the Union" has a deeply geographically separated nature, with different ethnicities living in very precise places (the most common example given, of course, is that of black people in Indiana, who reside almost exclusively across the Mississippi River, but it's far from the only example). Secondly, it explains the true nature of Burrism as an ideology that, despite supposedly espousing egalitarian ideology, ends up being deeply discriminatory, by espousing "cultural diversity" as a way to ignore any form of true integration of peoples. It is due to this that the Native populations of traditionally Burrite states are so deeply unintegrated into our nation that they even speak their own languages.

Indeed, Burrism is not the ideology of progress and equality that so many espouse. It is the ideology of fear, of poverty, of class warfare and division, and of segregation. Similar to European socialists, they state they wish to unify the entirety of the world's people in equality, but only strive for their divisions."

-Excerpt from the introduction of "It's the Burrism, Stupid!", a book published by Patriot Party (Calhounite) of New York Congressman Ferdinand Church.

"I can't ever hesitate,

Can't ever show some restraint,

Or they'll take and they'll take and they'll take.

But I'll keep winning anyway!

I'l change up the game!

Cast the die and raise all the stake,

And if there's a reason I seem to thrive when so few survive,

Then god-damnit, I'm crossing the Rubicon!

I'm crossing the Rubicon!"

Can't ever show some restraint,

Or they'll take and they'll take and they'll take.

But I'll keep winning anyway!

I'l change up the game!

Cast the die and raise all the stake,

And if there's a reason I seem to thrive when so few survive,

Then god-damnit, I'm crossing the Rubicon!

I'm crossing the Rubicon!"

-Change Up the Game, from Luis Manuel Moro's seminal Broadway show Hamilton, shows Burr deciding to march West, asking Hamilton for help but being rejected.

"Burr has been commonly known as the Sulla of America. For many, this title references the fact that he was an unabashed populist, who seeked to further his own political power through the political underclasses of America as Sulla did with the lower classes of the Roman plebeians. To others, this title references the supposed incidents of "Burrite Barbarism" during the Second American Civil War, bouts of barbarism that, although occasionally true, seem to be greatly exaggerated by propaganda from later periods, especially from official history of the United States written during the first period of the Jacksonian Era, strengthening in tone during the Period of National Emergency.

It's interesting that, while so many of the official lies propagated during the Period of National Emergency have been debunked by historians across the political spectrum, two seem to thrive in some areas of American politics: the idea that American instability arose from the First American Civil War, termed as Hamilton's Folly (while it's clear that, even previously, Americans had been notoriously rebellious, with the Whiskey Rebellion and Shay's Rebellion during the Washington Administration, as well as the conflicts between States during the early years of the Confederation and the Constitution of 1789, especially the Pennamite-Yankee War and the conflict that resulted in the creation of the Vermont Republic, indicate that the problem was more structural), and the idea that Burr's barbarism was out of bounds for an American civil war at the moment.

However, there is a major element of the Burrite period that generally has not been acknowledged by anyone, either Burrite or anti-Burrite, and which ties him extremely close to the Roman leader he is so often styled after: his extreme luck. Indeed, such as Sulla would eventually name himself Felix due to his bouts of great luck, Burr should've acquired a similar name. It would not be thought in 1808, despite the real threat the Union Army was under because of the Nullification Crisis and the First Civil War, that a small group of armed peasants and proletariats would be enough to deeply threaten the situation of the American Republic. However, the Burrite forces nearly destroyed the Madisonian democracy by 1812."

-Burr: A History of America's Sulla, by John Brightman.

---

-

Pilgrims were very often associated with Wabash colonists, in part due to the New England heritage of the first Wabashers.

While instability raged on the Eastern Seaboard, in 1805 Alexander Hamilton set off, tasked to found the new State of Wabash. Accompanied by his children, his wife and a small cohort of only about 300 people, it was clear to everyone, Hamilton included, that he was a political exile. Hamilton Grange, newly built by the family, was turned into a child's orphanage, in order to collect all funds possible for the state budget of Wabash, and the gruelling trip west to the new capital city, deemed to be Saint-Charles, set out.

The conditions in Saint-Charles, however, were not much better. The small hamlet's capacity was dwarfed by the new contingent, and the population was not exactly happy at seeing the first American governor of a State they did not belong to arrive. In fact, most of the few inhabitants didn't even speak English; Hamilton's fluency in French was the only thing that prevented an open shoot-out to start as soon as the settlers reached the city. Soon enough, the logistic incapability of the town became obvious, as food supplies clearly could not accomodate such a sharp rise in population. The entire hamlet, to the surprise (and the slight grumbling) of its original inhabitants, was moved from its location to be right at the other bank of the Missouri River from the larger Spanish town of San Luis, giving birth to the Twin Cities, as their current inhabitants know them today. What would eventually be considered a blessing was, at this point, considered greatly humbling to Hamilton and all Americans, who were essentially forced to depend on the Spanish for bare sustenance.

If the rocky start of the State of Wabash was troubling to Hamilton, however, it must be assumed that the newfound liberty he got from becoming the Governor and, until parliamentary elections in 1807, the sole legislative authority of the State of Wabash was extremely encouraging. Hamilton was at his most productive when writing the Wabash constitution, where he could finally establish a political society entirely to his liking. The Wabash Constitution was extremely detailed in its definition of the economic relations between the State and the people, the political rights of the population, and the remoteness of the Government from the day-to-day elector (even considering that, at the time of ratification of the Wabash constitution, only about 210 electors were recognized in the entire State). Perhaps the strongest deviation from the rest of the United States was the increased power the Wabash Governor had (and still has), as seen by the fact that the Governor, as per the State Constitution, can convene and dissolve Congress at any moment, determines the two Senators the State should send to the US Congress and has a whopping 10-year term (of which Hamilton was re-elected to three, before his death in 1826). Instead of the Congress, checks on the Governor are instead based on other "magistrates", borrowing from Roman inspiration, such as the popularly-elected pretor (more commonly known as the General Attorney), managing violations of law by State officials, as well as the questor (or comptroller), who has final say on budgets.

Surprisingly enough, the Constitution did not explicitly enshrine Wabash as a free State, instead remaining completely quiet on the issue. Modern historians seem to recognize in this two fundamental elements of early Wabash politics; first, the fact that Hamilton was not actually the progressive Abolitionist icon most Whigs paint him out to be. More importantly according to most modern Historians was the fact that Wabash was desperately looking for immigrants, and wanted to keep the door open to migration from the South. However, at this point in time, migration between States, and especially migration to the West, has become extremely rare. The previous actions of Hamilton towards the State of Virginia had shocked and horrified most State governments, which immediately seeked to fortify their National Guards, and strengthen their internal economies at the cost of inter-state commerce. While most States did not go as far as blocking migration to other States (this was an extremely contentious process, which resulted in an official request, as per the US Constitution's Section 10, of the State of Connecticut to prohibit migration west by its citizens, leading to an inconclusive conflict in the Supreme Court in which it determined it could not disavow an action that had not been done by the State Government, requiring of at least legal debate in the US Congress and the Connecticut Assembly first), there were great dissuasion processes to stop citizens of States to move to other States.

William Henry Harrison (pictured here), the first non-Hamiltonian governor of Wabash (1826-1835), was a famously pro-slavery Wabasher.

This meant that Hamiltonian democracy was forced to accept any person that arrived to the State, and for most of the early 1800s, that was mostly slaveowners seeking to take advantage of the fertile Ohio River basin, as well as Francophones coming over from Louisiana (a reason why Wabash is the only State of the Union to have French as an official language) and a few freedmen (although Hamiltonian agnosticism on slavery and the eventual creation of Indiana State would make this a very disheartening prospect for all but the most capitalist-minded freedmen). Still, immigration was rather scarce. By the election of 1808, the first time the new State was granted ordinary elections, the State of Wabash had a population of less than 7,000, under a fifth of what the second-smallest State of the Union (Ohio) had at the time.

Conditions in Wabash at this point were rather rough. The winters were hard, and Saint-Charles had little, if any, infrastructure to exert itself over its own territory - let alone the rest of the United States, which was one of the reasons why the notably mercurial Hamilton, who detested Burr and saw Madison in a relatively fond light, remained neutral during Burr's Rebellion. The only exception to this rule was the growth of trade in the State, which, due to its Hamiltonian roots and its proximity to Spain (and, eventually, Colombia), meant that it was extremely well-positioned to be a hub of American trade. While far-off even at the time of the death of Hamilton, Saint-Charles would be well off on its way not only to being the largest city in the American West but one of the commercial, industrial and banking hubs of the world.

Last edited:

Ah. Maybe change the burrite color? It being the Federalist orange is confusing. You could switch colors with the federalists.

Hi! You're absolutely right. The map formats have been changed, which includes adding Burrite red.

Chapter VIII - What About the West?

Sacagawea sighed as she looked at the endless Dakota plain. This can't be it, she thought. What a life she had been brought into! Stolen from her homeland by the nefarious Hiraacá, then used as a disgusting prize to be won by a white hunter. No choice at any moment, nothing to do other than tend to Monsieur Charbonneau. And, worst of all, at just fourteen, so heavily pregnant she could barely move. Is this really it?

In her dreams, things were so different. She was visited, almost rescued, by people who looked like Monsieur Charbonneau, but who were kind, and friendly, and didn't want anything from her, only her help. They would take her on the most fantastic adventures to the West, where she could once again meet her tribe, once again eat salmon with her Agaidika, once again see her father. She would use her knowledge of languages to meet and befriend new people; after all, she'd have to take what she had learnt from these terrible people to good use. She and her child would be taken away by these great men, and turned into great and famous figures, forever to be known in history. She would be free, and great, and famous.

Oh, what a fantasy. The kick of the baby and the gentle scolding of Otter Woman, who reminded her that the day was getting colder, and that soon Monsieur Charbonneau would be back, and expecting dinner to be ready. She had to get off her dreams and start cooking, for she wasn't Charbonneau's wife for nothing.

With a groan, she stood up. She swore this time her daydreams were true. Something had to give, eventually. Her rescuers would come.

But they never did.

-----

Preocuppied with the growing instability of the eastern States, the short-lived presidency of Thomas Jefferson, who had essentially acquired the new vast Missouri Territory as an afterthought of the bloody conflict in Virginia, did not have a great interest in actually surveying the new American lands. Despite comprising almost half of the current territory of the United States, the Missouri Territory was seen as a completely useless acquisition, seen as an affirmation of the French victory in the War of 1802, where they were not forced to cede either Spanish Florida, or, more importantly, what had been eyed by American traders to ensure control over the Mississippi Basin; the port of New Orleans. Instead, what was granted over was a territory that had no sea access, that implied a harsh and mostly unknown crossing to the Pacific, riddled with "savage" Natives who would not easily give in to American colonization.

However, something still had to be done - a territory was recently annexed to the United States, one that was rich on furs and resources, and which needed to be explored to see how to best exploit it for the well-being of the American people. Thus, an expedition had to be commissioned. The Corp of Expedition, led by Captain Merriwether Lewis and First Lieutenant William Clark, however, was fitted with the least resources possible, with only the two officers, four auxiliary soldiers and Lewis' slave leaving west from Pittsburgh in 1805.

However, things would soon go awry. While Lewis and Clark wanted to explore west in the easiest manner possible, taking the Missouri River as far west as it would take them, charting the border with Spain on the way, the government was extremely jittery towards triggering a new conflict with Colonial powers. Instead, Jefferson directly instructed the Corps of Discovery to go north along the route of the Mississippi River, reaching the Lake of the Woods (determined to be the northwesternmost edge of American territory after American independence) before, once again, heading south to take the Mississippi River as far west as it would take them, until the Pacific was discovered. Lewis and Clark, however, did not expect the mighty Mississippi ending long before the Lake of the Woods, leaving the small expedition to an arduous trek northward. The death of Clark's relative and closest friend Charles Floyd from appendicitis on what today is Floyd's Falls[1] and the posterior death of one of the expedition's two cartographers in or very near to the headwaters of the river from what seems to be the complications of a deathly allergy to a bee sting greatly demoralized the small group. A small raid by Ojibwe members of the Council of Three Fires, who seemed to initially think the Corps of Discovery was a particularly loud Iroquois expedition before the color of their skin was revealed, resulted in the injury of Captain Lewis himself, who determined that the expedition would have to turn around and be restocked and refitted for a safer Missouri river travel.

However, this would not be the case. Lewis was shot dead within weeks of returning to Pittsburgh, allegedly by William Clark's slave York, who was sentenced to death for the crime (although modern analyses point towards suicide, and the State Government of Indiana has officially pardoned York, despite the crime being judged before Pennsylvania court). Clark, on the other hand, would be sent to fight a Native insurgency in the State of Ohio, before becoming one of the most prominent officers of the Madisonite faction in the Western Front of the Burrite War, dying to a joint Burrite-Tecumseh strike against Madisonite forces in the Battle of Fort Hamar. It wouldn't be until the War of the Supremes that territory west of Wabash would be actually explored by an official American corps, and it would not be until well into the Jacksonian period of American history that the US Army would reach the Pacific Ocean.

The "cursed expedition" of 1805 was, however, very prominent in American perspectives of the "Wild West". Previously seen as a land of untamed opportunity and great riches, whose exploration even warranted rebellion and war (as had been seen when the British Crown tried to turn everything west of the Appalachian Mountains into an Indian Reserve and part of the Province of Quebec), the West started to be seen as dangerous and seedy, home to "Indians, Insurgents and Illnesses". Few Americans, other than those who had no choice (and further reinforced these stories; by 1807 everyone knew of the harsh situation Saint-Charles was under, and how they had to move to the other side of the river from Saint-Louis to stay alive, depending on Spanish aid for their sustenance; Burrite rebels and runaway slaves also made the Upper Mississippi their favorite place of settlement, making the area especially unpalatable to settlers from slave States who deeply opposed Burrite ideologies), would move West. States, concerned about losing any potential manpower of young males who could fight in their state guards against Federal tyranny, did not oppose these changes in public opinion towards the West. The idea of the West as a land of homesteaders, as wished by Jefferson and other Southern Governments before Hamilton's Folly, was dead.

---

(Tried to do something different, but as you can probably tell I suck at narrative writing, lol. We'll get back to Burr's War next chapter).

[1] OTL Saint Antony Falls, Minnesota

In her dreams, things were so different. She was visited, almost rescued, by people who looked like Monsieur Charbonneau, but who were kind, and friendly, and didn't want anything from her, only her help. They would take her on the most fantastic adventures to the West, where she could once again meet her tribe, once again eat salmon with her Agaidika, once again see her father. She would use her knowledge of languages to meet and befriend new people; after all, she'd have to take what she had learnt from these terrible people to good use. She and her child would be taken away by these great men, and turned into great and famous figures, forever to be known in history. She would be free, and great, and famous.

Oh, what a fantasy. The kick of the baby and the gentle scolding of Otter Woman, who reminded her that the day was getting colder, and that soon Monsieur Charbonneau would be back, and expecting dinner to be ready. She had to get off her dreams and start cooking, for she wasn't Charbonneau's wife for nothing.

With a groan, she stood up. She swore this time her daydreams were true. Something had to give, eventually. Her rescuers would come.

But they never did.

-----

Preocuppied with the growing instability of the eastern States, the short-lived presidency of Thomas Jefferson, who had essentially acquired the new vast Missouri Territory as an afterthought of the bloody conflict in Virginia, did not have a great interest in actually surveying the new American lands. Despite comprising almost half of the current territory of the United States, the Missouri Territory was seen as a completely useless acquisition, seen as an affirmation of the French victory in the War of 1802, where they were not forced to cede either Spanish Florida, or, more importantly, what had been eyed by American traders to ensure control over the Mississippi Basin; the port of New Orleans. Instead, what was granted over was a territory that had no sea access, that implied a harsh and mostly unknown crossing to the Pacific, riddled with "savage" Natives who would not easily give in to American colonization.

However, something still had to be done - a territory was recently annexed to the United States, one that was rich on furs and resources, and which needed to be explored to see how to best exploit it for the well-being of the American people. Thus, an expedition had to be commissioned. The Corp of Expedition, led by Captain Merriwether Lewis and First Lieutenant William Clark, however, was fitted with the least resources possible, with only the two officers, four auxiliary soldiers and Lewis' slave leaving west from Pittsburgh in 1805.

However, things would soon go awry. While Lewis and Clark wanted to explore west in the easiest manner possible, taking the Missouri River as far west as it would take them, charting the border with Spain on the way, the government was extremely jittery towards triggering a new conflict with Colonial powers. Instead, Jefferson directly instructed the Corps of Discovery to go north along the route of the Mississippi River, reaching the Lake of the Woods (determined to be the northwesternmost edge of American territory after American independence) before, once again, heading south to take the Mississippi River as far west as it would take them, until the Pacific was discovered. Lewis and Clark, however, did not expect the mighty Mississippi ending long before the Lake of the Woods, leaving the small expedition to an arduous trek northward. The death of Clark's relative and closest friend Charles Floyd from appendicitis on what today is Floyd's Falls[1] and the posterior death of one of the expedition's two cartographers in or very near to the headwaters of the river from what seems to be the complications of a deathly allergy to a bee sting greatly demoralized the small group. A small raid by Ojibwe members of the Council of Three Fires, who seemed to initially think the Corps of Discovery was a particularly loud Iroquois expedition before the color of their skin was revealed, resulted in the injury of Captain Lewis himself, who determined that the expedition would have to turn around and be restocked and refitted for a safer Missouri river travel.

However, this would not be the case. Lewis was shot dead within weeks of returning to Pittsburgh, allegedly by William Clark's slave York, who was sentenced to death for the crime (although modern analyses point towards suicide, and the State Government of Indiana has officially pardoned York, despite the crime being judged before Pennsylvania court). Clark, on the other hand, would be sent to fight a Native insurgency in the State of Ohio, before becoming one of the most prominent officers of the Madisonite faction in the Western Front of the Burrite War, dying to a joint Burrite-Tecumseh strike against Madisonite forces in the Battle of Fort Hamar. It wouldn't be until the War of the Supremes that territory west of Wabash would be actually explored by an official American corps, and it would not be until well into the Jacksonian period of American history that the US Army would reach the Pacific Ocean.

The "cursed expedition" of 1805 was, however, very prominent in American perspectives of the "Wild West". Previously seen as a land of untamed opportunity and great riches, whose exploration even warranted rebellion and war (as had been seen when the British Crown tried to turn everything west of the Appalachian Mountains into an Indian Reserve and part of the Province of Quebec), the West started to be seen as dangerous and seedy, home to "Indians, Insurgents and Illnesses". Few Americans, other than those who had no choice (and further reinforced these stories; by 1807 everyone knew of the harsh situation Saint-Charles was under, and how they had to move to the other side of the river from Saint-Louis to stay alive, depending on Spanish aid for their sustenance; Burrite rebels and runaway slaves also made the Upper Mississippi their favorite place of settlement, making the area especially unpalatable to settlers from slave States who deeply opposed Burrite ideologies), would move West. States, concerned about losing any potential manpower of young males who could fight in their state guards against Federal tyranny, did not oppose these changes in public opinion towards the West. The idea of the West as a land of homesteaders, as wished by Jefferson and other Southern Governments before Hamilton's Folly, was dead.

---

(Tried to do something different, but as you can probably tell I suck at narrative writing, lol. We'll get back to Burr's War next chapter).

[1] OTL Saint Antony Falls, Minnesota

It is a nice chapter. Well, maybe not for the people that got screwed... In any case, the narrative bits add an interesting and more personal touch to the timeline.

Chapter IX - The Start of Burr's War

Commonly known as La Federación de Burr, Hernán Palomino's Texan Federation, from his LT-175 (most commonly known as the timeline presented in the hit novel Los Monstruos de la Meseta) is one of the most famous works of alternate history in the modern day. Los Monstruos de la Meseta has been turned into a hit radio-show by the British Broadcasting Corporation, which has received many accolades and whose Texan merchandise (an example of which is shown below) has reportedly made over a billion dollars of revenue in the United States.

“There seems to be a degree of correspondence that has been lost due to the secrecy of Burr’s ordeal between November of 1808 and April of 1810. However, it does seem that Burr had extensive contact with Minister Carlos Martínez de Irujo and Governor of Louisiana Juan Manuel de Salcedo in the Spanish side, Thomas Dunn in Lower Canada as well as the French administration. All pledged to try and support Burr (feeble words, considering that all of the colonial states were busy back in Europe in the brunt of the Napoleonic Wars) but only the British provided anything resembling military support.

Initial correspondence seemed to make it unclear on whether to seek Spanish help in New Orleans to retake the American presidency by force, or to take over New Orleans himself and create his own American fiefdom in Louisiana. Eventually, he decided to do the first and arrange alliances to help him regain the United States.

A meeting with Governor Juan Manuel de Salcedo managed to show the unlikely prospect of Spanish aid in any conflict. Spain had recently been invaded by French forces in Europe, and all of Spain’s strength was focused on fighting off the invader - not on helping what they saw as little more than an inter-colonial dispute. Burr left Nueva Madrid disappointed, but not surprised, especially after the Spanish government determined that they would recognise his government as legitimate were he to take over the United States.

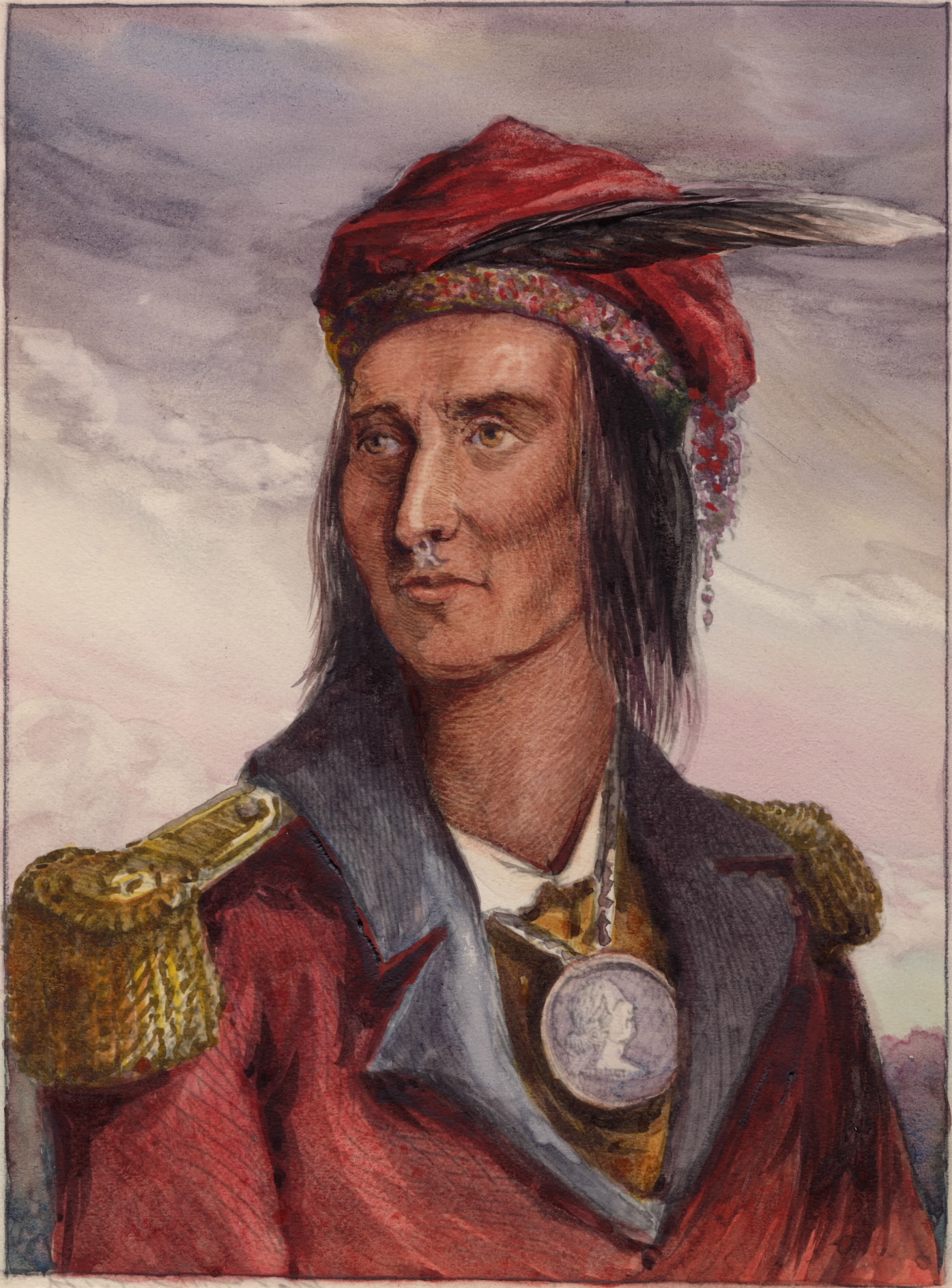

Burr, however, did find a native ally slightly further south, in the form of several native tribes within the United States that had previously been friendly to Government interests. They remembered Burr’s (at the time) radical progressivism fondly, and were concerned by Madison (as well as other Republicans, such as Monroe’s) support towards American settlers encroaching westward on their land. The previous war between Hamilton and Jefferson had stopped, at least for some time, American westward expansion - Natives hoped a new war would do so again, and that Burr, were he to retake the Presidency, would allow the Natives independence. Both the Five Civilised Tribes and the notorious Native warlord Tecumseh (at the time in Georgia trying to make the Tribes join his confederacy) met with Burr and agreed to help him retake the Presidency.

The Five Civilized Tribes (according to general American historiography; called the Founding Tribes by the Sequoyah State Government and the Insurgent Tribes by Carolinian historiography) were fundamental in Burr's War.

1810 started seeing a far stronger amount of raiding strikes by part of native armies. The Red Stick Muscogee, especially hit by the revival of Native religious practices influenced up north in the confederacy created by Tecumseh. Eventually, Georgian state forces had to call in Federal aid.

Led by General Andrew Jackson, nearly 5,000 American troops were dispatched to deal with the Red Stick Muscogee. Jackson’s forces made their way down the south with brutal efficiency, massacring a Muscogee raiding band near Gaffney, South Carolina, and moving into Georgia. They faced the Muscogee in the Horseshoe Bend in southwestern Georgia, expecting an easy victory.

Of course, they didn’t expect the Indians, who were camped at a bend, to start fighting so strongly - instead expecting that they would surrender quickly. They were even more caught out of guard once Burr’s forces appeared at the rear of Jackson’s corp. Jackson barely escaped the onslaught; almost 3,500 American soldiers (including Lieutenant Sam Houston and Colonel John Williams) weren’t so lucky. The appearance of Burr’s corps in the conflict made it clear - a new American civil war was to start.

Burr meats up with William Weatherford after the end of the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. An unlikely alliance, the Burrite-Native alliance would spell the end of the First Constitution.

Within two months of the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, several Federalist governments declared that their goal was not the protection of a purely Democratic-Republican ticket and declared their neutrality regarding the conflict. The state of Wabash, led by Alexander Hamilton, was the first to do so (afraid that any conflict with Natives would lead to Tecumseh raiding Wabash territory), but they were swiftly followed by New York and Vermont (where Burr was still extremely popular), and, within a week, Massachusetts and New Hampshire.

Further south, panic took hold of many State governments as both Jackson’s expeditionary corps and the State militias proved to be absolutely useless at stopping Burr’s forces, which crossed through Georgia taking over forts and arsenals. Even more panic arose as Burr announced that slaves that would take up arms against the government would be freed under his new administration. Within a year, almost a fifth of Georgia’s slave population had escaped plantations and joined Burr’s army. While this army of poor whites and freed blacks grew, it also marched, reaching the remnants of Jackson’s army off the Chattahoochee River (which today provides Georgia’s northeastern border with the resulting state of Muscogee (today Sequoyah)) - smashing the army and causing it to dissolve.

The damage to land in the American West was large and widely-spread. Property rights were so muddled it wasn't until the 1857 landmark case, Smith v. Tennessee, that legal precedent on "the Tennessee Land Troubles" was set down by the Supreme Court. Burr's War was used as an argument in court over property disputes as late as 1898.

The Jack Johnson reserve in Tennessee, founded in 1847, is famously the only whiskey reserve to have survived "the distiller's curse"; as all distillers of brandy, whiskey and gin in the state of Tennessee were shut down over land issues related to Burr's War and the War of the Supremes. Interestingly enough, the Tennessee State Government has spoken out about the "distiller's curse", refusing to recognize it; instead, as 38% of lawsuits about land issues came from a resident of Kentucky, the State of Tennessee argues that the lawsuit frenzy in the XIXth Century was a trick done by the State of Kentucky to keep the rival Tennessee whiskey industry from growing.

Native forces mostly led by the Muscogee, meanwhile, were busy occupying and raiding white settler colonies in western North Carolina and Tennessee. They saw this territory as their land and were focused on expelling white settlers from the territory - which, by October of 1810, led to an almost full occupation of both Tennessee and Kentucky - with only small reducts of American soldiers positioned in the Mississippi holding out against the Native incursion and protecting American settlers. The destruction of farms and plantations in both Tennessee and North Carolina is still perceptible to this day - land ownership in the two states became extremely confusing in the ensuing five decades, which led to a notable slowdown in the settling of the two States.

Led by Upper Creek chief William Weatherford (also known as Red Eagle to his native soldiers), the Native armies occupying Kentucky then decided to move north and meet up with the forces of Tecumseh’s Confederacy amassing in Western Ohio. Initially, Weatherford tried to cross through the eastern part of the State of Wabash and thus avoid conflict with Ohioan settlers - seeking to minimise his losses before moving east into Pennsylvania. However, Wabash, which had implemented a sort of State Guard, stopped them in their attempted Ohio River crossing.

Knowing that, if he were to fight with the Wabash State Guard, the State would begin opposing the Rebellion and thus create a third frontline that would surround Tecumseh’s forces, Weatherford decided against crossing the Ohio River by force, and instead moved eastwards and crossed it in the state of Ohio. The small town of Cincinnati, not expecting warriors from Ohio, was taken easily - including the semi-abandoned Fort Washington, which provided more ammunition to the rebels. With this, Weatherford was ready to join up with Tecumseh.

Tecumseh’s troops had attracted a relatively large Army force into Ohio seeking to expel them from State lands and back into the Indiana Territory. This army, almost 8,000 soldiers strong, had already defeated Tecumseh’s forces one in a sortie, and were moving into Western Ohio to do so again. Tecumseh was ready to fall onto them around Delaware territory in the State, where he and Weatherford’s 3,500 Cherokee and Creek soldiers were ready to fight.

The Battle of Delaware was an absolute bloodbath, with General William Henry Harrison’s American force being taken completely off guard. A combination of Western battle tactics by part of Weatherford’s forces and Native guerrilla tactics and surrounding by part of Tecumseh saw the Army decimated, with the remnants fleeing into eastern Ohio.

The tide seemed to initially turn due to overextension. Too long supply lines and conflict between Southern and Northern natives meant that Tecumseh and Weatherford did not coordinate as well as they should have - and in early 1811, the advance was fought back before reaching the eastern border of Ohio. Of course, Harrison’s forces were too depleted to take the bulk of the state, but they did stop incursion into Western Pennsylvania. Things also went badly for Burr’s corps in Virginia, when it was soundly beaten back by a Federal force led by Jackson, which pursued the fleeing army back into North Carolina.

Burr’s rebellion, albeit initially very strong, seemed to be at the brink of ending.”

-Excerpt from “Native Autonomy and Aaron Burr” by Charles Ridge. Published by Harvard University, 1978.

Last edited:

Chapter X - "WI Stronger America?"

Retrieved from uchronia.com Discussion

What If: Stronger United States

What If: Stronger United States

John_Locke said:How would it be possible to avoid the United States going into a secondary status in the Americas? I know it seems like the United States was doomed from the start, surrounded by two great powers and limited by the conflicts between way too different states, but is it in any way possible to arrange a system that makes the United States an important regional power? Maybe even a world power?

DEMOSTHENES said:You’d need Flying Magic Octopuses (FMO) for this to hapen. No way the United States becomes that strong. They were sandwiched between the United Kingdom and Colombia (which have traditionally been diplomatically close), and had huge internal differences. No way that traders in the North, plantation owners in the South and trappers and independent farmers in the West would ever become allies of each other.

A lot of people compare the early United States to early Colombia, but that’s unfair. Though geographically much larger, the social and economic systems were far more similar in all of Spanish America - there wasn’t any major ethnological differences between the different States until the twentieth century, there was Creole landowner dominance everywhere, and the country was (and to a degree remains) uniformly Catholic. None of that is true in the United States.

Deganawidah said:Now, I don’t think it’s as impossible as (useremosthenes) thinks. I do agree, though, that it’s a tall order.

I think the easiest way is preventing Hamilton from usurping power from Adams in 1800. That might provide for a far more stable United States. Though even later PODs are possible.

That being said, I do think it becomes borderline FMO after Burr’s Rebellion. The Rebellion really broke the back of the First Constitution - unity was shattered and it would take a long to bring the United States back together into a strong sense of national unity.

Pedro Juárez said:I think it’s absolutely impossible for the US to become a superpower as long as the borders remained as is. As they stand, they were barely a transcontinental power until the 1920s: it’d be far easier if they had the extensive natural wealth of Luisiana and California, and the geographical advantage of not having to protect their territory from incursions from either La Florida or Nova Scotia. The shared ownership of the Lower Mississippi River ensured that no conflict involving the United States and Colombia would happen without shattering the former country’s economy.

John_Locke said:Now, I think the prevailing pro-Colombian bias of this netsite is showing. At the time of Burr’s Rebellion Colombia didn’t even exist - it’s a bit absurd to say that it was predestined since before independence to become the undisputed master of most of North America.

That being said, avoiding the conflicts that wrecked the United States for so much of the first two-thirds of the nineteenth century would go a long way. Without those, maybe westward expansion would go better - we did see a glimpse of that with Thomas Jefferson’s request to map the Oregon Country in the brief period of peace between Hamilton’s Folly and Burr’s Rebellion.

If you avoid most civil wars (I don’t think all of them are necessary, though the earlier the better) - and, by the War of the Supremes, it's way too late - the US has a strong demographic advantage regarding Colombia, which only truly settled Louisiana starting from the homesteading Decrees of the 1840s.

DEMOSTHENES said:If anything, there’s a Colombiaphobic attitude in this thread. Of course the country wasn’t predestined to rule, but it had a real demographic advantage over the United States in that there wasn’t so much of a conflict between the different parts of the country as there was in America between States. Hell - after Burr’s Rebellion there were States that directly opposed any expansion into Native land, how exactly do you expect these States to readily join in in conquering other countries?

The fact is, as long as there’s a political division such as there was in the United States there’s no way it can become a world power, much less in the XIX Century. In Colombia, Liberals and Conservatives (and even Francistas) agreed in a lot of things - the fight between Democrats, Republicans and Federalists in the United States was a fight to the death. There’s no way a country so shakily built as the United States - one that for such a long time had half of the country literally supporting slavery, and the other half divided between abolitionism and general dislike of the institution - can expand that shakiness abroad, much less when it’s so surrounded by united, militarily strong, allied nations. Any war to gain land by the United States against either Colombia or Britain would end in disaster, as can be seen with the general blockade that would prevent General Jackson from going into war with Colombia in the 1830s.

Aureolin said:Not to add that the United States had a nasty habit to fix all its issues with violent conflict. It’s often forgotten that the first rebellions against the United States Government happened before George Washington even left the Presidency. Sure, those pale in comparison with Burr’s Rebellion and the War of the Supremes (not to speak of the War of Emancipation) but they were there - and they were only slightly smaller than, say, Hamilton’s Folly in scope.

Retrieved from uchronia.com Discussion

What If: Stronger United States

Dear @Fed

your latest post is un thread marke.

Thanks for that! It's been fixed

Hey, I'm currently reading through this TL and I just finished The Age of Burr. One small thing I feel the need to point out. You need to pick a different VP for Madison. He can't run with Monroe because they're both Virginians. Unless the Constitution is different in that regard in this TL, two men from the same state can't run together. Other than that, I'm loving this so far! Great work!

If the OP decides to change it, maybe William Crawford? IIRC he was considered the only person who could have challenged Monroe for the nomination in 1816 meaning they likely had similar friends/allies and he was the most prominent non-Virginian.Hey, I'm currently reading through this TL and I just finished The Age of Burr. One small thing I feel the need to point out. You need to pick a different VP for Madison. He can't run with Monroe because they're both Virginians. Unless the Constitution is different in that regard in this TL, two men from the same state can't run together. Other than that, I'm loving this so far! Great work!

Actually, since the process of selecting the VP hasn't changed from it's original runner up form, and since the ticket won in such a landslide, they could still be elected together, but Virginian electors would have to vote null or for a throwaway candidate for VP, as it's only electors from the home state in question that can't cast a ballot for both. Also there was an error in the description of the 1804 electoral map, with the map saying he got 154 (less than Madison), but the description saying he got 159.

Also some confusion; if Adams got 65 electoral votes, more so, than Thomas Jefferson's 52, then why is Jefferson mentioned as being sworn in as vice-president elect? Adams should be vice president elect in such a case, unless the electoral map is also wrong.

Also some confusion; if Adams got 65 electoral votes, more so, than Thomas Jefferson's 52, then why is Jefferson mentioned as being sworn in as vice-president elect? Adams should be vice president elect in such a case, unless the electoral map is also wrong.

Last edited:

Threadmarks

View all 33 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter XXIV - "My Crown for the Paraná". The Election of 1838 Chapter XXV - En un coche de agua negra.... Chapter XXVI - ... Iré a Santiago. Chapter XXVI.5 - Blackness in Colombia Chapter XXVII - No Continent for Enslaved Men Chapter XXVIII - Francia, Domestic Edition Chapter XXIX - The Last Emperor Chapter XXX - The Mandate Shifts - Southern China in the Qing Collapse.

Share: