You're right that that's an error. It's been corrected.Do you mean 'right or left"?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

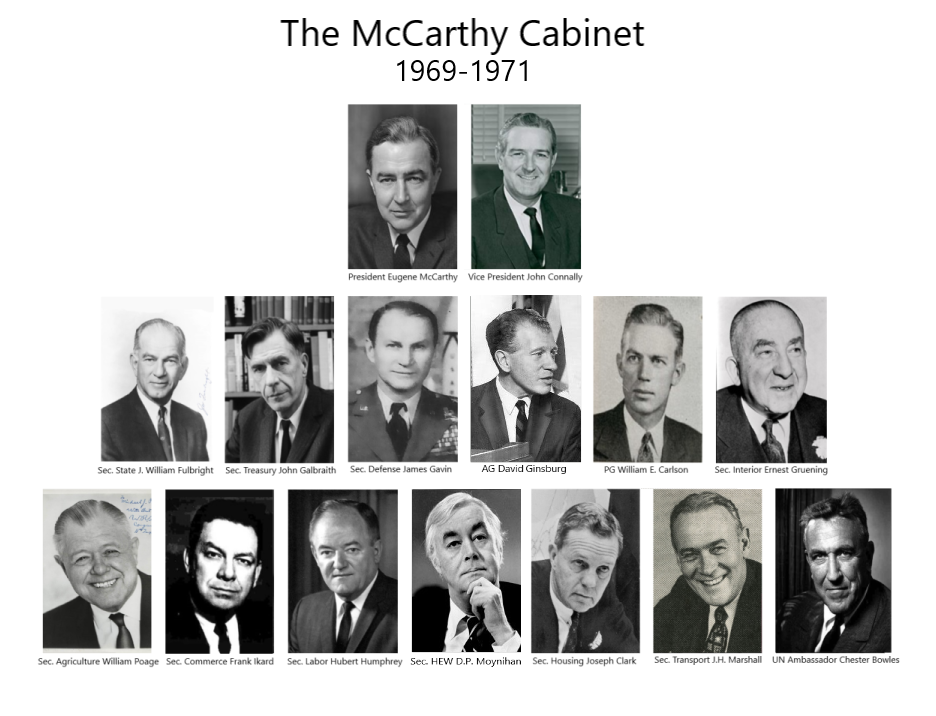

Give Peace Another Chance: The Presidency of Eugene McCarthy

- Thread starter The Lethargic Lett

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Threadmarks

View all 20 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

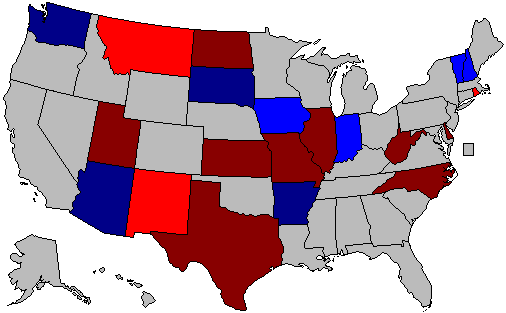

Chapter Six - Fortunate Son The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour: Its Origins and Near-Death Chapter Seven - Medley: Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In (The Flesh Failures) The Decline of the Hippie and the Rise of the Cleagie: Woodstock, Manson, and Altamont Chapter Eight - We've Only Just Begun The 1970 Midterm Election Results Chapter Nine – Bangla Dhun Ah, After 10,000 Years I'm Free!I'll adjust the colours around the time the next chapter is posted at the latest.Good stuff but it is kinda hard to tell the difference in color between Reagan and Rockefeller as well as between Humphrey and Wallace

Chapter Five - Vote For Gene McCarthy

Chapter Five - Vote For Gene McCarthy

In one of the more bizarre political alliances in American history, both anti-war protestors and Southern delegates celebrated the best possible outcome of a bad situation, in the form of the nomination of Eugene McCarthy and John Connally.

Unlike the carnage of the past week, the final two days of the convention brought a relative peace to the city of Chicago. Even many of the New Left protestors who claimed to hate McCarthy at least attended the celebration in Grant Park, but for their own ends. In particular, Tom Hayden of the Mobe still tried to radicalize the protestors, claiming they were, “a vanguard of people who are experienced in fighting for their survival under military conditions.” However, any remaining hopes the New Left had of keeping ideological control of the protestors ended with the arrival of McCarthy himself. Introduced to the stage by the famous black comedian Dick Gregory, McCarthy gave a quick address, joking that it was easier to get into Grant Park than the convention hall, and proclaimed to the protestors that his nomination proved that they could work within the system. Following McCarthy’s departure, Hayden tried to convince the audience that McCarthy had sold out by aligning himself with the South, but it was clear that all but the most militant of the New Left would be working for McCarthy until the election.

While the New Left considered the Chicago riots to be a great victory, the rest of the country disagreed: polling indicated that a majority of Americans sided with the police, and forty percent of voters who favoured unilateral withdrawal from Vietnam believed that the Chicago police had used insufficient force. In the weeks following the Democratic National Convention, the Mobe saw a massive decline in active participation, as their core membership, the liberal-to-moderate antiwar middle class, abandoned the organization in droves to volunteer for the McCarthy campaign instead [1]. However, even with an influx of support from members of the Mobe, the Democratic Party was in an absolute shamble. After Chicago, McCarthy dropped five points in the polls below his Republican opponent, Richard Nixon, while the third party bid of the archsegegregationist George Wallace was rising in popularity [2]. Many of the union and Democratic state leaders who had been expecting an easy convention victory for Humphrey were blindsided by McCarthy’s nomination, and were reluctant to give him their support, despite a speedy endorsement from the Vice President [3]. Likewise, the alliance with the South was off to a rough start, as Connally had to answer awkward questions from the press on why he had suddenly decided to support McCarthy when he had, for over a year, castigated him as a party-wrecker and soft on communism. To top it all off, McCarthy’s national headquarters had reached a state of near-total paralysis; any sort of chain of command had completely eroded in a clash of conflicting responsibilities, personal rivalries, and mixed messages. It was only made worse by three new layers of office politics, when both former Kennedy and Humphrey political advisors, Southern political operatives working for Connally, and the Democratic Party’s official apparatus all tried to worm their way into the campaign. Nearly collapsing under its own weight, the McCarthy national headquarters was divided between the original grassroots Dump Johnson supporters led by Curtis Gans, McCarthy’s pre-campaign Senate staff led by Jerry Eller, McCarthy’s small team of political professionals led by Tom Finney, the Stevensonian Wall Street bankers represented by Thomas Finletter, Kennedy carryovers led by Richard Goodwin and Pat Lucey, Humphrey carryovers led by Fred Harris and Walter Mondale, Connally loyalists and Southern advisors led by Robert S. Strauss, and representatives of the new, McCarthy-appointed Democratic National Committee Chair Philip H. Hoff [4]. With his national headquarters incapable of making any centralized decisions, McCarthy’s chances of being elected were entirely at the mercy of the state parties, and most of them refused to cooperate. This left Nixon with a clear path to the White House, and everyone knew it. The only person who did not seem concerned was McCarthy himself, who continued to hold a blasé, academic, and moralistic opinion on presidential politics. Deciding to ignore the opinion polls entirely, he would simply present himself to the voters, and they would decide.

Texas' Favourite Son, Governor John Connally, at the 1968 Democratic National Convention with his delegation.

Richard Nixon was in the midst of the greatest political comeback in American history. Having previously served two terms as vice president as the running mate of President Dwight Eisenhower, Nixon had narrowly lost the presidency to Jack Kennedy in the Election of 1960. Attempting to regain his footing, in 1962, Nixon ran for Governor of California, where he went down in embarrassing defeat to the incumbent Democrat. Declaring, “You won't have Dick Nixon to kick around anymore,” his political career seemed unquestionably over. However, despite what appeared to be the brutal end of his chances for elected office, Nixon remained quietly involved in Republican affairs. In the 1964 Republican primary, Nixon discreetly tried to position himself as a compromise candidate between the party’s conservatives, represented by Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona, and the party’s moderate-liberal Eastern Establishment, represented by Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York. Although Goldwater had been able to quickly secure the nomination at the 1964 Republican National Convention, the bitter infighting and Goldwater’s fringe positions paved the way for Lyndon Johnson’s crushing landslide victory, but, it also left an opportunity for an uncontroversial figure to step in and unify the party. Nixon, who had since moved to New York to work for the prestigious legal firm Nixon Mudge Rose Guthrie & Alexander (with himself as the newly added titular Nixon), used his new connections in New York law to hire an inexperienced but enthusiastic and innovative new staff to prepare for a presidential run in 1968. Prominently campaigning for many Republicans during the 1966 midterm elections, Nixon had established himself as the man to beat for the Republican nomination. His only clear opponent had been Governor George Romney of Michigan, a Rockefeller-backed member of the Eastern Establishment. However, under intense media scrutiny, Romney’s campaign self-destructed before the primaries had even begun, after a gaffe where he remarked he had been “brainwashed” into supporting the Vietnam War, as well as a statement by Rockefeller indicating that he would be entering the race himself. In the aftermath, Romney withdrew. However, Rockefeller, unsure of his chances, denied that he would be running, leaving Nixon unopposed in the primaries. By the time Rockefeller formally announced, Nixon had already swept the primaries, and many delegates who might have otherwise supported him were already committed. On the other end of the party was Governor of California Ronald Reagan. Formerly an actor, Reagan had laid the foundations for his political career by vocally supporting Goldwater in 1964, and had swept into office in a landslide in 1966, in part because of Nixon’s midterm campaigning [5]. Laying claim to the conservative wing of the party, Reagan was equally hesitant to attempt to directly challenge Nixon, for fear that it would cause a split similar to 1964. As the convention opened in Miami Beach on August 5th, Nixon deftly played the two wings of the party off of each other; by stoking fears of a Rockefeller nomination, he was able to gain the support of conservative Republicans such as Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina and Barry Goldwater himself, both of whom would otherwise have supported Reagan. Additionally, by presenting himself as the guaranteed, uncontroversial, inevitable winner of both the nomination and the election to come, Nixon was able to hold enough support with delegates from the Midwest and Mid-Atlantic who might otherwise have supported Rockefeller. With this deft political manoeuvring, Nixon was able to narrowly win the nomination on the first ballot. Wishing to keep things as simple as possible, decided to choose a non-entity as his vice president, in the form of Governor of Maryland Spiro Agnew. Agnew had previously been one of Rockefeller’s most fervent supporters, but Rockefeller’s earlier declaration of non-candidacy embarrassed Agnew, who had boldly declared Rockefeller’s imminent candidacy, and had brought several reporters into his office to watch the 'campaign launch,' only for him to declare he was not a candidate. Agnew had then switched his loyalties to Nixon, and had secured the Maryland delegation for him during the nominating process. Nixon believed that the moderate, unknown Agnew would be a safe choice as his running mate.

Once nominated, Nixon prepared to implement the strategy he had been setting up for years. As far back as 1966, Nixon had been specifically planning on running against Johnson in 1968. To that end, he had spent his time out of office cultivating an image as a respected elder statesman, providing very public 'helpful' criticism of the President. Always waiting for a moment of weakness, Nixon would tut and wag his finger at every setback in Vietnam, riot in the streets, or unpopular economic decision. Presenting himself as above the fray and an experienced administrator, Nixon hoped to make his core demographics the traditional Republican voters of rural areas and suburbia, as well as expand into those demographics in the South, where they had traditionally voted Democratic. In order to garner the support of the South and middle America, Nixon adopted a vague, mild-mannered opposition to social disorder, crime, government overreach, and Johnson's handling of the Vietnam War. He promised he would not support school busing desegregation, and pledged to appoint less “activist” judges to the Supreme Court. The latter point was a reference to the judicial activism of Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren. The Warren Court had been one of the most famously liberal in American history, making landmark decisions on civil rights, criminal procedure, the separation of church and state, and other issues. With Warren himself retiring, there was an opportunity for whoever won the election to appoint a new Chief Justice and redefine the courts. Nixon's call for judges who would more strictly adhere to the Constitution carried the implication that judicial appointments under a Nixon Administration would at least slow the nation's rapidly accelerating social progress. However, as part of his centre-right strategy, Nixon conceded the traditional Democratic demographics of the Midwest and Mid-Atlantic, namely, urban, ethnic, unionized, and black voters. Believing that his plea to the “forgotten American” implicitly included middle class unionized and black voters, Nixon made no special effort to try and win them over. As for Vietnam, Nixon nebulously promised “peace with honor,” and questioned the means by which the war was being fought, but not the ultimate goal of a negotiated peace that would ensure South Vietnam's continued existence. Although surprised by McCarthy's nomination, Nixon did not change his strategy, believing that McCarthy would not be able to overcome the fundamental differences within the Democratic Party. Nixon's chief concern, at least for the time being, was the populist upstart campaign of former Governor of Alabama George Wallace.

"Nixon's the One." Visiting Chicago shortly after the Democratic National Convention, Nixon emphasized his law and order credentials, and drew up to four hundred thousand attendees.

George Wallace had gained infamy when, in his inaugural address as Governor of Alabama in 1963, he had declared that there would be “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” Wallace’s political origins had begun in the 1958 Alabama gubernatorial election. Running as a Democrat in what was at the time a one-party Democratic state, he had earned a reputation as a moderate by Alabaman standards by supporting racial segregation but opposing the Ku Klux Klan. Losing in the Democratic primary to his overtly racist and pro-Klan opponent, Attorney General of Alabama John Patterson, Wallace vowed to never be “out-niggered” again. In the intervening years, Wallace carefully crafted a reputation as an ardent opponent of desegregation, and mixed the issue in with a right-populist brew of opposition to communists, liberal eggheads, stuck-up federal bureaucrats, sanctimonious Washington judges, and black provocateurs out to destroy the Southern way of life. Although campaigning focused almost entirely on social issues, Wallace also included a moderate economic course of low taxes, fiscal responsibility, and make-work projects. With nearly the exact same percentage of the vote that Patterson had gotten in 1958, Wallace defeated his more moderate opponent in the Democratic primary, and went on to win in the general election with ninety-six percent of the vote. Once governor, Wallace engaged in a series of grand-standing confrontations with the federal government as it tried to enforce desegregation, most infamously in his ‘Stand in the Schoolhouse Door,’ where he physically put himself between the University of Alabama and two new black students attempting to register, with their entry ultimately being enforced through an executive order by President Kennedy.

As 1964 approached, Wallace began to prepare for a primary challenge against Kennedy, beginning a nationwide speaking tour where he praised states’ rights and local governance, and denouncing what he called federal overreach. Wallace believed that as a Southern right-populist, he would be the perfect foil to the liberal Catholic President. Ignoring the obvious implications of advocating for states’ rights at a time when many states where doing everything in their power to interfere with federal civil rights legislation and court rulings, Wallace denied that he was racist, or had ever intentionally appealed to racism to boost his political career. Instead, he blamed racial unrest on corrupt politicians and communist activists ‘tricking’ the black population of the South with “false promises of a utopia,” and that, “The Negro has not received any ill-treatment in the South.” To anyone familiar with segregation, Wallace was obviously lying. As Governor, he had organized brutal crackdowns of civil rights demonstrators by using the Alabama Highway Patrol, run by his henchman Albert J. Lingo, as his own security force. Additionally, through a quid pro quo network of extremist supporters in the Ku Klux Klan and National States’ Rights Party, he had a handful of radicals willing to engage in terrorist attacks on his behalf [6].

Throughout 1964, Wallace preyed on ingrained racial fears amongst America’s white populous. He frequently and falsely claimed that the Civil Rights Act would result in the government seizing white suburban homes to give to black people, and would give black citizens special legal treatment over anyone else. Even after President Kennedy was assassinated, Wallace decided to go through with his primary challenge against the new President Johnson. Putting up a rhetorical smokescreen, Wallace would dodge the most controversial or pointed questions sent his way with a disarming joke, and would always couch his language in the terms of small government rather than in the rhetoric of overt racism. Running against a trio of favourite sons, Wallace would ultimately get around thirty-three percent of the vote in the Wisconsin primary, slightly under thirty percent in the Indiana primary, and forty-three percent in the Maryland primary. Wallace exceeded all expectations of his chances in the Midwest, and won an outright majority of white voters in Maryland. Wallace’s core demographic outside of the South had been white lower middle class suburban voters, who were typically first or second generation Americans. Being from the lower income suburbs closest to urban centres with high black populations, the ‘Wallace vote’ had been those white voters who most directly felt the growing prosperity of the black community, as they began to move into the same lower middle class suburbs as them. The Wallace vote’s economic anxiety became inseparable from their inherently racist beliefs that black neighbours would threaten their jobs, lower their property values, increase crime, and decrease the quality of local schools.

Running under the banner of the American Independent Party, Wallace had returned in 1968, and enjoyed enough support nationwide to appear on the ballot in all fifty states. Sticking to the performance that he had been refining for nine years, Wallace distanced himself from overt segregationism, and relied more and more on dog whistle racism. Running a robust 'law and order' campaign in which he vilified student protestors, anti-war activists, and black Power advocates as a gang of communists and criminals given protection by a godless, overly-permissive federal government. 'Vote for George Wallace,' he seemed to say, 'and the government will finally look after the little guy, the responsible citizen, and do away with all the kooks and crazies.' Similarly sticking to bread and butter economic issues, Wallace promised lower taxes and smaller government. On Vietnam, he was simultaneously the most dovish and hawkish of the three major candidates, as he promised to give the military's Joint Chiefs of Staff complete control of the war effort, and if they could not win in sixty days, he would have America unilaterally withdraw. Wallace's base remained largely confined to rural and lower middle class voters, but with a nationwide audience and social anxiety at an all time high, he garnered massive support from unionized workers in the Midwest, and reached nearly twenty percent in the polls, and threatened to deadlock the Electoral College, preventing any clear winner [7].

"Stand Up For America." George Wallace shakes hands at a rally. Preying on social and racial anxiety, Wallace led a potent, populist campaign in 1968.

It was in this tumultuous political environment that the McCarthy campaign found itself adrift. McCarthy held to the same positions he always had, and waited for the electorate to come to him. He continued to refuse to make any serious campaign decisions, and remained reliant on his staff and state volunteers to prepare events for him. He continued to advocate for a negotiated settlement in Vietnam that would include a complete bombing halt and democratic elections in which the National Liberation Front would be allowed to participate. On the economy, his chief proposals remained a universal basic income proposal, and the implementation of the findings of the Kerner Commission, which called for a dramatic increase in social security and welfare spending. McCarthy did not avoid his policy positions, but his natural inclination to meandering and philosophical speeches obfuscated the issues, as he focused on the nature of America and its institutions. McCarthy called for a more limited role for the president, a restoration of America's societal-moral fabric, and a calm, reflective analysis of the issues facing the country. None of McCarthy's policy proposals were particular popular, but his own popularity did not seem to be tied to theirs; a majority of Americans held a positive opinion of him, he was especially liked by independents, and had significant Republican crossover appeal. Ironically, during the Democratic primaries, he had performed weakest among Democrats, who consistently preferred Kennedy or Humphrey to him. His strongest demographic, the suburban middle class, had, in large part during the primaries, been Republican and independent cross-over voters.

With McCarthy's quixotic appeal, his chances of victory would be entirely determined by turnout. The greatest battle between Nixon and McCarthy would be over the suburban middle class, with the traditional Democratic demographics on the periphery. If McCarthy failed to rally the traditional Democratic demographics and trigger a large turnout, it would undermine his percentages enough that his popularity with the middle class would be irrelevant. Alternatively, the same result could have been reached if Nixon had made any concerted effort to win over voters in the traditionally Democratic demographics.

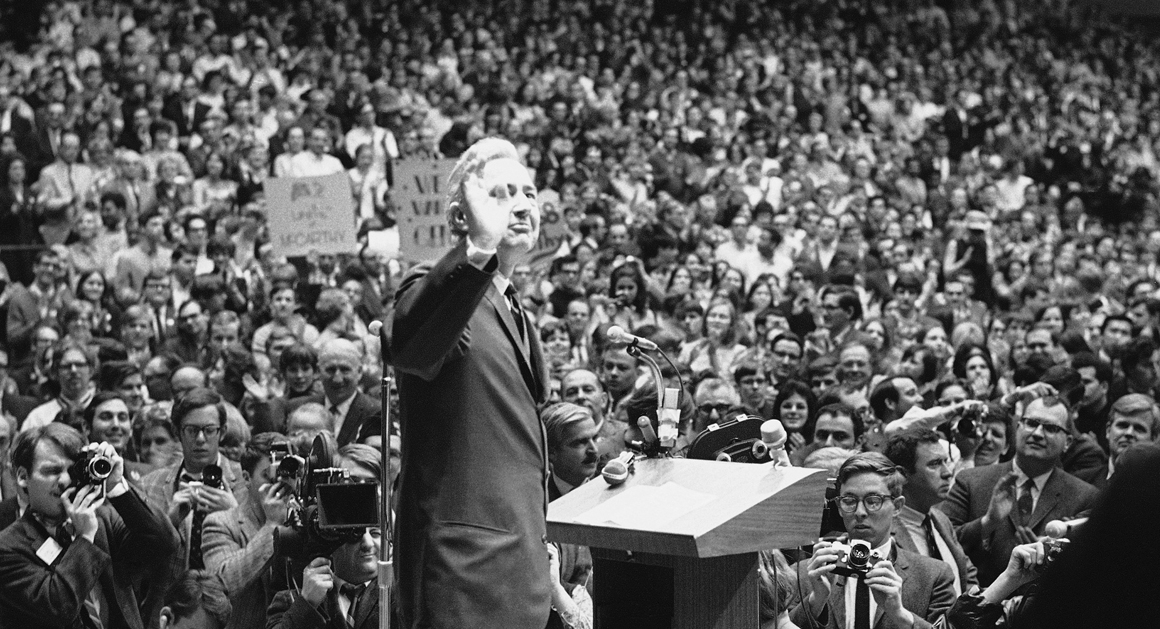

"Let Us Begin Anew." McCarthy greets a packed arena in the Midwest. The final outcome of the Election of 1968 would be determined by McCarthy's ability to effect turnout.

As September arrived and with the election less than two months away, McCarthy's base began to slowly coalesce, all while his campaign continued to coast on well organized state volunteers. The Democratic National Committee, once the puppet of President Johnson, no longer had the energy or resources to resist their own presidential candidate, no matter how much distaste there was for him; the organization had been left in deep debt and on a shoestring budget during the Johnson years. In fact, the weakness of the DNC and the state parties that Johnson had caused by consolidated the party's resources in the White House was a major contributor with the surprising effectiveness of McCarthy's challenge. Philip Hoff, as the new DNC Chair, was shocked to discover that office staff was being laid off to cut costs in the middle of an election. No advertising department existed, and there was literally no money in their spending account. Circumventing McCarthy's national headquarters for its own good, Hoff began the arduous process of sorting through the dozens of bank accounts that McCarthy's campaign had been using, where millions of dollars sat unused. Ecstatic with McCarthy's nomination, the Wall Street Stevensonians collectively donated hundred of thousands more, and a glut of oil money poured in from Texas: McCarthy's longstanding support for the oil industry was finally reaping its rewards, and was multiplied by Connally presence on the ticket, having served for years as a lobbyist for Texas' oil tycoons. Small dollar donations also began pouring in from the suburban middle class. The millions of dollars raised or rediscovered in early to mid-September was not enough to sustain the entire campaign, but presented a much-needed windfall to the DNC. Under Hoff's direction, the lay-offs were reversed, an advertising agency was put on retainer, and McCarthy's general campaigning expenses and television appearances were paid for [8].

McCarthy also had the luxury of being adored by the press, with it being difficult to find a single negative word printed about him. Arthur Schlesinger Jr, the famed 'court historian' of the Kennedy Administration, remarked, “They didn't know McCarthy, but they were suddenly seized by the notion that here was this man, a poet himself, a friend of poets, that had the courage to lift the banner of opposition to the war. He was a romantic figure and suddenly came out of nowhere, and everyone could find in him their vision of what the country needed.” Humphrey's personal physician, Edgar Berman, added, “Humphrey... watched with mounting amazement as line by line, drink by drink, the press consensus built that poetic Irishman's myth.” McCarthy's calm, deliberate style came off incredibly well on television, and was the optimal method for him to communicate his ideas to the public without the demagoguery of having to convince them face-to-face. The right-leaning press found him equally hard to hate, with McCarthy's conservative style being positively compared to such Republican stalwarts as Calvin Coolidge and Robert Taft. Even the archconservative himself, Barry Goldwater, admired him, and admitted that if a Democrat had to win in 1968, he was glad it was going to be McCarthy.

However, despite this, the party remained fractured throughout September. In the aftermath of McCarthy's nomination, the only states with state Democratic leadership devoutly committed to him were California, Oregon, and Wisconsin. There were many states where McCarthy had a polling lead, but where the anti-McCarthy sentiment in the state leadership called the ultimate turnout and results into question, such as in Illinois, Pennsylvania, New Jersey. There were still more states where beleaguered McCarthy volunteers had to pick up the slack from completely unsupportive state party and union leadership, such as in Ohio and Michigan. The only major unions that had quickly come around to support McCarthy had been the United Automobile Workers (UAW) and the International Brotherhood of Teamsters [9]. The biggest and most powerful union in the United States, the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), remained aloof. George Meany, the President of the AFL-CIO, was a supporter of President Johnson and the Vietnam War, and was reluctant to support McCarthy [10]. Even with Humphrey on his side and pleading his case to Meany and the AFL-CIO leadership, union support remained elusive for McCarthy for the rest of the month.

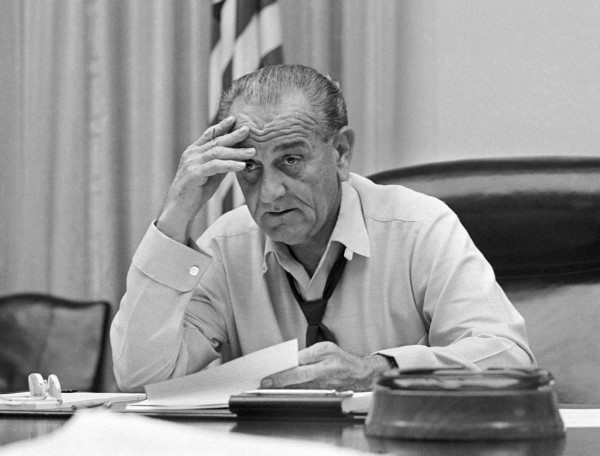

Meanwhile, President Johnson was trying to save his legacy. Johnson's gradual escalation of the Vietnam War during his presidency was in large part because of his insistence that he would not be the first president to lose a war, as well as misleading, overly-optimistic reports from the military. With only two months until his transformation into a lame duck president was complete, Johnson was determined to negotiate an end to the war on his own terms. While Johnson's pro-administration plank had been the more hawkish of the two at the Democratic National Convention, the President was genuinely trying to negotiate an end to the war as quickly as possible. Johnson had believed that a bombing halt would endanger American soldiers and prolong the war, as it would allow the North Vietnamese to marshal their resources without any pressure. He had believed that the bombing of military and urban civilian targets in North Vietnam was the peace position, as it would beat the North Vietnamese into submission and force them into an agreement sooner. Such were the absurdities of geopolitics that a significant escalation of bombing was, in its own way, considered an offer of goodwill. However, in the same March speech in which he had declared he would not seek a second term, Johnson had also declared he would halt most of the bombing of North Vietnam, but only under the expectation that the enemy would make a similar move toward peace. During the summer, he was informed by Soviet leadership that they were encouraging the North Vietnamese to reach an agreement. By September, as the rainy season began to arrive in Southeast Asia, the President was informed that bomber accuracy would approach nil, and that a complete bombing halt could be put in place starting in October without compromising the safety of American troops. But, at the same time, Johnson began surreptitiously offering advice and support to Nixon, who he believed was closer to his foreign policy view than McCarthy, and who he felt would be a more responsible negotiator as president. Likewise, Johnson forbade anyone in the cabinet or executive office from helping McCarthy in any way.

In the meantime, Nixon was getting nervous. In several essential swing states, namely California, Illinois, New York, New Jersey, and Oregon, McCarthy had a lead in statewide polling, despite trailing behind Nixon nationwide, and it was beginning to look like a possibility that the election might be deadlocked after all. With that in mind, Nixon doubled down on his strategy of portraying himself in a better light. A large part of his campaign had been around creating a “New Nixon.” A mature man of reconcialition, even-handedness, coolness, and confidence. This image was designed to bury the reputation of the “Old Nixon,” who was remembered as surly, hostile, and slavishly committed to (Joe) McCarthyism. As part of the New Nixon, many campaign decisions were made with the failures of 1960 particularly in mind: the 1960 Kennedy-Nixon debate made him look bad, so debates would be avoided; in 1960 he had looked by on television, so radio advertising was prioritized; in 1960 he had overworked himself, so he took at least two days off a week; in 1960 he had made too many decision himself, so he delegated nearly everything to his advisors; and in 1960 he had been too inaccessible, so he went out of his way to cater to the press. Believing his downfall to be a poor media portrayal in 1960, Nixon revolutionized how politics were portrayed to the public, under the auspices of his media advisor, Roger Ailes. The fixation on radio and television portrayals went so far that Nixon's advisor, H.R. Haldeman, recommended eliminating all personal appearances. Although they did not go to that excess, Nixon spent more time in front of a microphone or camera than any other presidential candidate in history, with the goal of creating at least one newsworthy soundbite a day. In an attempt to “capture and capsule” spontaneity, Ailes developed a new method of presenting a candidate. Nixon was put on a circular stage, enveloped by an audience who fielded questions for up to ten hours at a time. The audiences were pre-selected but the questions were not screened, and Nixon's best answers were cut together into commercials and television and radio spots that portrayed him as a relaxed, super-informed elder statesman. Both the circular 'arena' shape and the editing of the footage was designed to subliminally make voters sympathetic to Nixon. Rather than try and appeal to voters with reason or policy issues, Nixon wanted an emotional impression to be what was remembered. Nixon's best speeches from the primaries were also recycled and re-released in print and on radio as targeted advertising. However, by the nature of its own efficiency, the campaign began trapped in the political centre, in a presentation that was, as Nixon's speechwriter Pat Buchanan put it, “programmed, repetitious and boring.” Unwilling to deviate from the plan of assembling a coalition of the Republican base plus suburbia to win, Nixon's advisors who he had delegated most campaign decisions to, cancelled meetings with unions, on campuses, and in ghettos, fearing that presenting Nixon in an uncontrolled environment in front of an unsympathetic demographic might lead to some sort of confrontation or gaffe that would ruin the New Nixon image. Likewise, Nixon was hesitant to take a clear, hawkish position on the Vietnam War or be especially critical of McCarthy, as Johnson was privately insisting, as he feared that it would alienate the suburban swing voters who would be the key to the election. Rather than discuss policy, Nixon talked more of his personal philosophy on the nature of the presidency. When policy did emerge, it was in general terms of law and order, and peace with honour, rather than a thorough analysis of a problem facing the nation. The press, quickly tiring of Nixon's repetitive stump speeches, began to write more and more on his lack of substance rather than anything he was actually saying.

Unlike Nixon, who had an almost too well organized campaign, or Wallace, who tended to improvise but always had an idea of what he was doing, McCarthy's campaign stayed true to its character as a ramshackle crusade across the nation. In spite of this, it seemed to be working. In a year where social anxiety and a sense of powerlessness was stronger than ever, many voters were paying closer attention to personalities than policies, who McCarthy, who was once described as, “the very antithesis of social turbulence,” was a comforting presence. He was doing notably well in the Upper South. Drawing larger crowds than either Nixon or Wallace in Virginia [11], many assumed that McCarthy was some sort of conservative, with his talk of the constitutional limits of the presidency and the importance of citizen participation within the political process. Ironically, Wallace's talk of small government and states' rights as a racial dog whistle also benefited McCarthy to an extent, as many took McCarthy as someone who would not strenuously push for desegregation, when, in fact, he had been doing so his entire career.

"The Year of a Continuous Nightmare." Lyndon Johnson desperately tried to redefine his legacy in the latter days of his presidency.

As October arrived, greater attention was paid to the three vice presidential candidates.

To say that John Connally was mistrusted by McCarthy's staff was an understatement, and the two running mates barely appeared together. Despite this, Connally was an asset to the ticket, at least in the South. Staying below the Mason-Dixon Line for nearly the entire campaign, Connally gave a further conservative spin to McCarthy's conservative style. Having been a fierce hawk on Vietnam for years, Connally began to ignore the topic as much as possible, and when confronted with it, dismissed any concerns by stating he was bound by the peace plank passed at the convention, and quickly changing the topic [12]. On touchy subjects like busing desegregation, Connally would dodge the question by referring to McCarthy's belief in constitutional limits, knowing full well that McCarthy was entirely supportive of busing desegregation. Connally also remained quiet on economic issues for the most part, where his fiscal conservatism only agreed with McCarthy when it came to lowering taxes. Too slick and experienced a politician to get caught in a gaffe or controversy, Connally caused no great harm to the ticket, and was an effective campaigner in the South [13].

At the same time, Spiro Agnew caused all sorts of problems for the Republicans. Nixon remembered his poor treatment during his time as vice president under Eisenhower, and insisted that Agnew be given respect and significant autonomy by the campaign team. This began to backfire, as the politically inexperienced Agnew – having served less than one term as the governor of his home state of Maryland – staggered from one gaffe to the next. Too blunt for his own good, Agnew referred to Polish-American voters by the derogatory term “polacks,” described a Japanese-American reporter as “the fat Jap,” and claimed that, “if you've seen one slum you've seen them all.” His effectiveness as Nixon's attack dog was also called into question, when he was lambasted by the press for comparing McCarthy to British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, a leading proponent of appeasing the Nazis. Agnew's knowledge of his opponent's policies was also mocked, when he dismissed the Democrat's housing policy as unworkable, then proposed a nearly identical policy of a public-private partnership that would build affordable suburban housing for black people otherwise financially trapped in the ghetto. Unwilling to take advice from Nixon's policy team, and with Nixon unwilling to reign him in, Agnew staggered through the campaign. Despite this, he was especially popular among conservative voters for his law and order campaigning, and 'tell it like it is' attitude.

As for Wallace, he had yet to officially pick a running mate. Wallace's friend, the former Governor of Georgia Marvin Griffin, had been used as a stand-in in states where a running mate was required to appear on the ballot, but Griffin had barely campaigned, and spent most of his time fishing. Wallace and his team began searching for a replacement running mate, with one of the first choices being Ezra Taft Benson. Benson had been the Secretary of Agriculture under the Eisenhower Administration, and was enthusiastic about the idea of joining the ticket. However, he was a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, one of the governing bodies of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (more commonly known as the LDS Church). The President of the LDS, David McKay, forbade Benson from appearing on a ticket with Wallace, for fear it would be a public relations fiasco for the Church. Wallace's next choice was Albert 'Happy' Chandler, the former Governor of Kentucky. Having been in a state of semi-retirement for nearly a decade, Chandler was excited with the idea of being on a presidential ticket, and was willing to become Wallace's running mate. Wallace was unsure, as Chandler had supported integration of the Major Baseball League during his time as the Commissioner of Baseball, and had supported the desegregation of schools in Kentucky shortly before he left office. But, it was these very facts that made Chandler a respectable figure to Wallace's staff, with one aide remarking, “We have all of the nuts in the country; we could get some decent people – you working one side of the street and he working the other side.” Wallace acquiesced, and leaked Chandler's selection. However, shortly after, an uproar emerged among Wallace's supporters. His state chairman in Kentucky complained that Chandler was, “an out-an-out integrationist” and resigned in protest. The Wallace electors of Kentucky and three other states also threatened to resign, which would have removed Wallace's name from the ballot in the four states. Wallace's biggest donor, the oil tycoon Nelson Bunker Hunt, also phoned to voice his displeasure. Wallace ultimately sent his aides to inform Chandler that he would have to be removed from the ticket. A third choice, former Air Force Chief of Staff Curtis LeMay was rejected as being too hawkish, when the presence of McCarthy as the Democratic nominee made it clear that the public was turning against the war [14]. With every single sitting member of Congress refusing to serve as his running mate, Wallace eventually approached Colonel Sanders, of Kentucky Fried Chicken fame, to see if he would join the ticket. Appealing to Sanders' pride as a Southern gentleman, and by insisting he was not racist (as well as setting aside a one million dollar trust fund for him), Wallace convinced the Colonel to run [15]. Although having no political experience and being treated as a joke by the press, Colonel Sanders' enthusiastic support for the American Dream added a positive spin to an otherwise very angry political movement. However, Sanders caused some problems for Wallace as well, as he quickly lost his temper under intense questioning, and had a tendency to rate the physical attractiveness of women while they were still in earshot. Ultimately, Colonel Sanders' down-home brand of Kentucky Fried Politics did not particularly help or harm Wallace's efforts.

Kentucky Fried Politics. Colonel Harland Sanders, the famous fast food mogul, served as George Wallace's running mate in the Election of 1968.

As the election came ever closer, the most reluctant key components of the New Deal Coalition finally began falling behind McCarthy. Despite his lukewarm relationship with the black community, civil rights leaders admitted that McCarthy's plans to improve conditions for black Americans were the fastest to help if implemented. Touring congregations across the country, Ralph Abernathy, Martin Luther King Jr.'s successor as President of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, remarked that neither candidate was particularly good, but that black people should vote for McCarthy anyway, as, “tricky, slicky Dicky” would be a disaster for black America [16]. A firm endorsement for McCarthy by Coretta Scott King also helped, as did campaigning by Ted Kennedy on McCarthy's behalf in ghetto communities. While McCarthy had never been at risk of losing a majority of the black vote, these combined factors guarenteed a level of support consistent with past elections.

As for the leadership of the AFL-CIO, they had ultimately realized that they were more afraid of Nixon than McCarthy. While Nixon never had any great support among unionized workers, Wallace did; in several polls of unionized workplaces, Wallace came out on top [17], and it was believed that a big enough Wallace vote would skew the results toward Nixon. After over a month of delay, the AFL-CIO finally formally endorsed McCarthy [18]. As one member of the AFL-CIO's Committee on Political Education (COPE) remarked, “Don't let anybody kid you that there's a new Nixon. Nixon's the same union-hater he's always been.” Holding positions from as far back as the 1940s against him, the union leadership convinced itself that a Nixon Administration would, among other things, destroy collective bargaining and abolish the National Labor Relations Board. In a media blitz, the AFL-CIO and its subsidiaries sent out enough anti-Wallace pamphlets for every unionized workplace in America. The contents described his anti-union positions, his support for right-to-work laws, and the low wages and benefits in Alabama. However, despite this late-coming support for McCarthy, the unions did not extent their efforts to down ballot doves, who often had to defeat union-endorsed candidates in the Democratic primaries in order to win.

By late October, McCarthy had passed Nixon in the nationwide polls. Despite the lackadaisical pace of his campaign and the shallow support of many of the state parties, the sheer quantity of his volunteers did most of the work for him, carrying a candidate who was close to dead weight at times. And, after entering the lead for the first time, many state parties participated in a last minute surge of support for McCarthy, for fear that they would be deprived of any favours if he were actually able to pull it off without them. Wallace's support began to diverge, as, in the Midwest, union voters were returning to McCarthy, while in the South, he was holding on to more of his vote; those who might have otherwise voted for Nixon in order to stop an overtly liberal Democrat from getting elected were simply not as afraid of McCarthy as they would have been afraid of Humphrey or a Kennedy. At the same time, Johnson's declaration of a bombing halt to save his own reputation and try and negotiate a peace arrived just in time to give McCarthy a coincidental last minute boost. Nixon, terrified of the possibility of yet another narrow presidential defeat, hatched a plot to prevent a last minute ceasefire in Vietnam. To that end, he recruited Anna Chennault, a Chinese-American anti-communist lobyist, to get in contact with South Vietnamese Ambassador Bùi Diễm. Working at least in part through Agnew, who would receive information from Chennault, Nixon encouraged Bùi Diễm and South Vietnam's president and dictator, Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, to hold out on the negotiations, with the expectation that they would get a much better deal if Nixon were president. Tipped off by a New York businessman, Johnson ordered the South Vietnamese embassy and Nguyễn Văn Thiệu's office wiretapped, had Chennault put under surveillance, and had the FBI track the phone calls coming out of Agnew's office. Confronting the Republican Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen, Johnson accused Nixon of treason by violating the Logan Act, which forbade private citizens from negotiating with foreign governments, and threatened to reveal the information to the public. In a phone call with Johnson on November 3rd, Nixon denied the accusations. Johnson, still believing that Nixon would be a better president than McCarthy, and, lacking any direct evidence of Nixon's involvement, did not push further, and withheld the information from the public [19].

The election finally arrived on November 5th, after one of the most tumultuous years in American history. Nixon spent his last day hosting a telethon, where he took questions live for four hours. McCarthy held a televised rally in Madison Square Garden in New York City, where a litany of celebrities, poets, and politicians praised his candidacy, with the event taking on more and more of the characteristics of a poetry slam as it went on. Wallace, for his part, returned home to watch the results come in from Alabama.

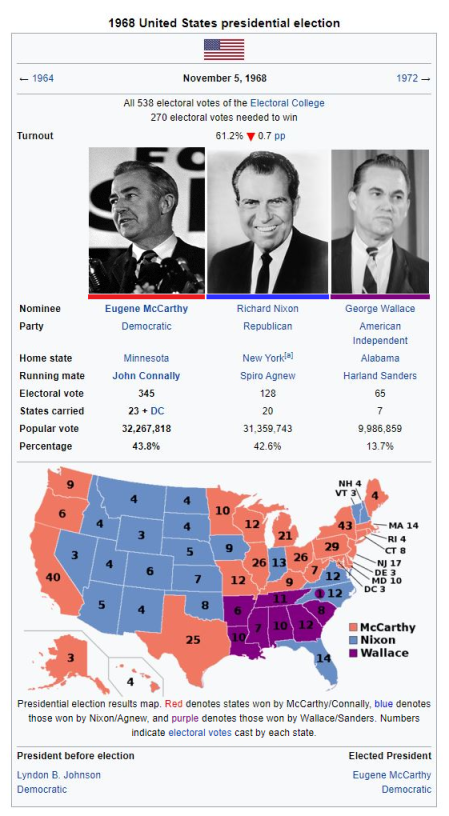

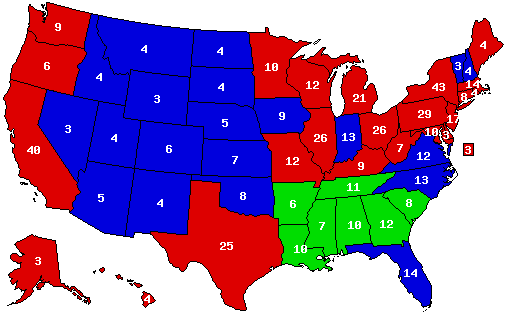

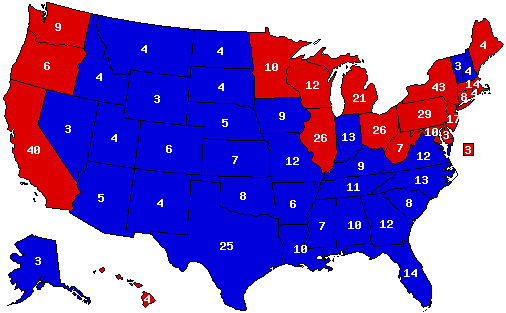

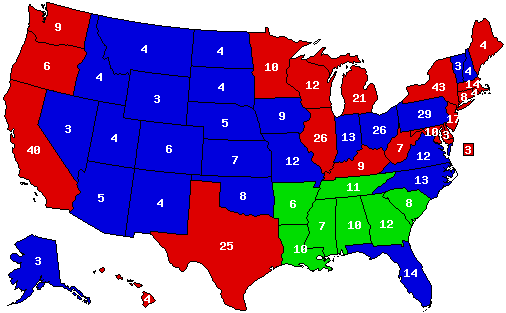

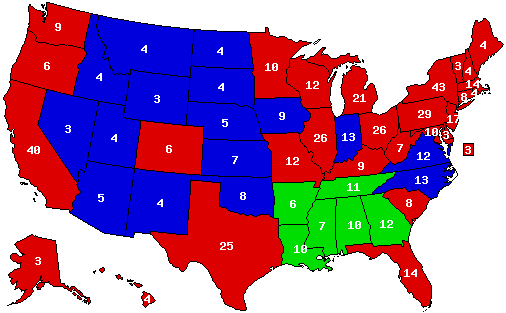

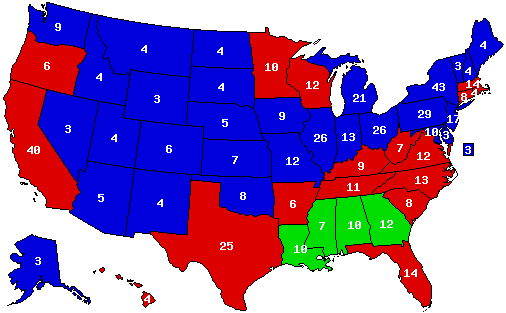

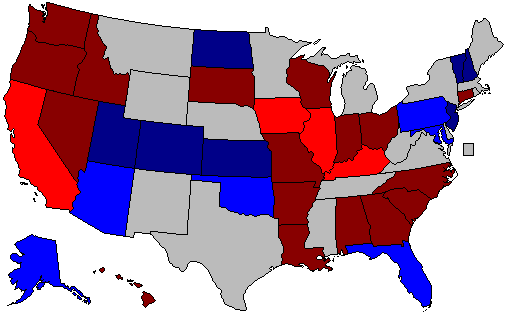

Many expected it to be one of the closest elections in American history, and the early results seemed to agree. The swing state of Kentucky was too close to call, and much of the Midwest tallied votes for long periods of time before declaring a winner. But, as the counting went on long into the night, it became clear that Nixon's plan had backfired. Relying too much on his own inoffensiveness and the suburban vote, he had been defeated in both categories by McCarthy, who was more popular in personality polls, and with the suburban population. Having failed to cultivate any sort of effort to steal away votes from traditional Democratic demographics, Nixon was buried in the Electoral College, despite the fact that he was within a few narrow percentages in the popular vote. In the South, Wallace had taken the lion's share of the states, and vote splitting between Wallace and Nixon had thrown several border states to McCarthy. It had developed into one of the most surprising upsets in American history, much like most political events McCarthy participated in.

Thus, the long odyssey of Eugene McCarthy was over, from a hopeless challenge against the incumbent president, to a brutal drawn-out battle in the primaries, to a seemingly impossible effort to attain the Democratic nomination, and, finally, to the highest office in the land; an office that he both barely wanted, and had craved for his entire political career.

As for George Wallace, he had failed to deadlock the Electoral College, but he still had a strong base of support to launch future presidential bids.

And, in their desire to put forward a candidate who could be all things to all people, the Republican Party forgot that Richard Nixon was a loser.

[1] ITTL, the final day of violence in Chicago was averted, including an incident where the Chicago police broke into McCarthy’s campaign headquarters and began beating up his staff, reportedly in retaliation against McCarthy staffers throwing objects from the office windows. There are conflicting reports on if McCarthy’s staff actually did begin throwing things from the windows: there are third party accounts from New Left protestors that confirm that at least some McCarthy staffers came into the streets to join the protests after their candidate lost the nomination. However, several McCarthy staffers agreed that the windows to their offices were sealed, so they could not have thrown anything, but they also agree that some things were being thrown from the roof of the building. There are conflicting reports on if the debris being thrown from the roof were being thrown by McCarthy staffers, New Left protestors, or by a Chicago police false flag operation.

[2] Just as in IOTL, McCarthy has dropped five percent in polls following the Democratic National Convention. This is still much better than Humphrey’s sixteen-point drop. While McCarthy’s reputation was still negatively affected by the convention, it was not nearly to the same extent as Humphrey; both ITTL and IOTL, the news media turned against Daley, and by extension Humphrey, due to their rough treatment by the police and convention security. Because of this, a lot of the coverage tended to skew toward McCarthy being portrayed as the ‘good guy,’ leaving his personal reputation relatively intact.

[3] According to Humphrey, before the convention, both he and McCarthy came to an agreement that they would endorse the other if he won, though McCarthy made Humphrey aware that he would not be able to endorse him until at least mid-September. IOTL, McCarthy was so angered by the mistreatment of his staff and the rejection of the peace plank that he refused to endorse Humphrey until late October. ITTL, Humphrey has upheld his side of the bargain, and endorsed McCarthy shortly after his nomination.

[4] Governor of Vermont Philip H. Hoff is McCarthy’s choice for Chair of the DNC ITTL. An anti-war liberal Democrat, Hoff is not running for another term, and will be able to devote all his energies to the chairship. IOTL, Humphrey selected Fred Harris as the new Chair.

[5] While Nixon’s support probably gave Reagan some credibility in the 1966 California gubernatorial election, with the unpopularity of the incumbent Democratic governor, Pat Brown, Reagan probably could have won without Nixon’s help.

[6] Through his far right connections, Wallace was at least partially responsible for the infamous 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing. Using Albert Lingo as his proxy, Wallace encouraged J.B. Stoner, the leader of the National States’ Rights Party (NSRP), to cause a disturbance big enough that Wallace would have an excuse to declare school integration too dangerous to implement. Stoner and the NSRP went on to hold various rallies and pickets against desegregation, and threatened to kill pro-desegregation officials. Meanwhile, at the same time that Wallace was warning state officials that communist civil rights radicals would try and blow up a black community centre as a false flag operation, Robert Chambliss, a Klan member infamous for using dynamite to blow up the homes of black families moving into white neighbourhoods, and who frequently attended NSRP meetings, began preparations to blow up the black 16th Street Baptist Church. The bombing would ultimately kill four black children: Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, and Denise McNair. Lingo, likely working under Wallace’s orders, then arrested the bombers for the misdemeanor crime of “illegal possession of dynamite” before there was any significant evidence to convict them for the murders. Eventually, after a few months, the FBI had assembled enough evidence to prove the bombers guilty, but J. Edgar Hoover called off the investigation to avoid the embarrassment of admitting that Chambliss was a long-time FBI informant. Chambliss was eventually convicted in 1977, and died in prison in 1985. Of the three other bombers, Bobby Cherry and Thomas Blanton Jr. were convicted in 2002 (Cherry died in prison in 2004, Blanton died in prison in 2020), while Herman Cash died in 1994, having never any prison time.

[7] It was unclear what Wallace’s ultimate goal was in the Election of 1968. Even in his most optimistic internal projections, his electoral ceiling was one hundred and seventy-seven electoral votes (winning Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia), which was not enough to win the presidency, but was enough to guarantee a deadlock in the Electoral College. When at the height of his polling, Wallace planned to refuse to release any of his electoral votes, and force the election into the House of Representatives, where Humphrey would have likely won, and where he could reaffirm his position as the only clear opponent of liberals presidential administrations for a future electoral confrontation. When he dipped in the polls and his margin looked weaker, Wallace began considering making a deal with Nixon to prevent Humphrey from getting in.

[8] Financially speaking, McCarthy was much better off than Humphrey at this point in the campaign. IOTL, all the large donors who might otherwise supported Humphrey had already spent millions of dollars, and were not willing to donate more to someone who was not their first choice. Likewise, the Texas oil money that had come in like clockwork for the Democratic Party each election year dried up for Humphrey, who had no particular appeal to conservative millionaires from the South. Humphrey did not receive any significant donations at all until he gave his September 30th speech in Salt Lake City, where he finally broke from administration plank that he had supported at the convention, and in which declared he would be willing to call for a unilateral bombing halt as, “an acceptable risk for peace.” Only after this break from the Johnson Administration did he start raising money in any noticeable capacity, including two hundred and fifty-thousand dollars in small dollar donations from the same kind of anti-war middle class voters that McCarthy had from the beginning. IOTL, it took Humphrey until October 10th to raise over a million dollars. ITTL, McCarthy had easily surpassed that number over a month earlier.

[9] The Teamsters, motivated entirely out of spite against Bobby Kennedy, was the only major union to support McCarthy during the Democratic primaries. The notoriously corrupt president of the Teamsters, Jimmy Hoffa, had a longtime rivalry with Kennedy, that originated when Kennedy, in his capacity as Attorney General, launched several criminal investigations against Hoffa. During the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, a mysterious man known only as “Mr. Johnson” was sent to help out McCarthy. This Johnson, an expert in phone surveillance, checked all of McCarthy's phones for wire tapping, and did security sweeps of his staff's offices. It is unknown if he found anything. A common joke among McCarthy's staff was that Mr. Johnson was the most honest man in world, because he had been arrested hundreds of times but never convicted.

[10] Humphrey, always a close friend of the unions, received their wholehearted support from the leadership of the unions from start to finish in his presidential campaign.

[11] This is not an exaggeration or ahistorical addition. McCarthy actually did draw larger crowds in Virginia than any other candidate in 1968.

[12] Connally was so hawkish that he had privately advised Johnson to nuke North Vietnam, but that was not the kind of thing he would reveal on the campaign trail.

[13] IOTL, Humphrey's running mate, Edmund Muskie, was extremely popular on the campaign trail, and was easily the most well-liked of the three vice presidential candidates.

[14] IOTL, Wallace chose LeMay as his running mate, something he would come to regret after LeMay, in his first appearance with Wallace, went on a rant about how the country had a, “phobia about nuclear weapons.” Claiming, “I've seen a film of Bikini Atoll after twenty nuclear tests, and the fish are all back in the lagoons, the coconut trees are growing coconuts, the guava bushes have fruit on them, the birds are back... the rats are bigger, fatter, and healthier than they ever were before.” Widely reported in the press, LeMay's remarks horrified Wallace, and his rapid drop in the polls in October was at least partially due to LeMay attempt to vindicate the use of nuclear weapons.

[15] Colonel Sanders actually was under consideration as a possible running mate by Wallace. The trust fund set up ITTL for the Colonel was created for LeMay IOTL.

[16] Abernathy said the same thing about Nixon and Humphrey IOTL.

[17] In one poll from a General Motors plant in New Jersey, Wallace won over seventy percent of the vote. While no nationwide polls were done, at his height, Wallace had the loyalty of about a third of unionized workers.

[18] Humphrey had the full support of the unions from the start, and their support was instrumental in picking up the slack from his lack of DNC funds.

[19] The same course of events happened IOTL, but played out slightly differently. IOTL, Johnson informed Humphrey, but both believed that the evidence was circumstantial, and would ruin the integrity of the presidency if the information was leaked and Nixon was elected anyway. ITTL, Johnson has a similar line of reasoning, but does not bother to tell McCarthy about it.

In one of the more bizarre political alliances in American history, both anti-war protestors and Southern delegates celebrated the best possible outcome of a bad situation, in the form of the nomination of Eugene McCarthy and John Connally.

Unlike the carnage of the past week, the final two days of the convention brought a relative peace to the city of Chicago. Even many of the New Left protestors who claimed to hate McCarthy at least attended the celebration in Grant Park, but for their own ends. In particular, Tom Hayden of the Mobe still tried to radicalize the protestors, claiming they were, “a vanguard of people who are experienced in fighting for their survival under military conditions.” However, any remaining hopes the New Left had of keeping ideological control of the protestors ended with the arrival of McCarthy himself. Introduced to the stage by the famous black comedian Dick Gregory, McCarthy gave a quick address, joking that it was easier to get into Grant Park than the convention hall, and proclaimed to the protestors that his nomination proved that they could work within the system. Following McCarthy’s departure, Hayden tried to convince the audience that McCarthy had sold out by aligning himself with the South, but it was clear that all but the most militant of the New Left would be working for McCarthy until the election.

While the New Left considered the Chicago riots to be a great victory, the rest of the country disagreed: polling indicated that a majority of Americans sided with the police, and forty percent of voters who favoured unilateral withdrawal from Vietnam believed that the Chicago police had used insufficient force. In the weeks following the Democratic National Convention, the Mobe saw a massive decline in active participation, as their core membership, the liberal-to-moderate antiwar middle class, abandoned the organization in droves to volunteer for the McCarthy campaign instead [1]. However, even with an influx of support from members of the Mobe, the Democratic Party was in an absolute shamble. After Chicago, McCarthy dropped five points in the polls below his Republican opponent, Richard Nixon, while the third party bid of the archsegegregationist George Wallace was rising in popularity [2]. Many of the union and Democratic state leaders who had been expecting an easy convention victory for Humphrey were blindsided by McCarthy’s nomination, and were reluctant to give him their support, despite a speedy endorsement from the Vice President [3]. Likewise, the alliance with the South was off to a rough start, as Connally had to answer awkward questions from the press on why he had suddenly decided to support McCarthy when he had, for over a year, castigated him as a party-wrecker and soft on communism. To top it all off, McCarthy’s national headquarters had reached a state of near-total paralysis; any sort of chain of command had completely eroded in a clash of conflicting responsibilities, personal rivalries, and mixed messages. It was only made worse by three new layers of office politics, when both former Kennedy and Humphrey political advisors, Southern political operatives working for Connally, and the Democratic Party’s official apparatus all tried to worm their way into the campaign. Nearly collapsing under its own weight, the McCarthy national headquarters was divided between the original grassroots Dump Johnson supporters led by Curtis Gans, McCarthy’s pre-campaign Senate staff led by Jerry Eller, McCarthy’s small team of political professionals led by Tom Finney, the Stevensonian Wall Street bankers represented by Thomas Finletter, Kennedy carryovers led by Richard Goodwin and Pat Lucey, Humphrey carryovers led by Fred Harris and Walter Mondale, Connally loyalists and Southern advisors led by Robert S. Strauss, and representatives of the new, McCarthy-appointed Democratic National Committee Chair Philip H. Hoff [4]. With his national headquarters incapable of making any centralized decisions, McCarthy’s chances of being elected were entirely at the mercy of the state parties, and most of them refused to cooperate. This left Nixon with a clear path to the White House, and everyone knew it. The only person who did not seem concerned was McCarthy himself, who continued to hold a blasé, academic, and moralistic opinion on presidential politics. Deciding to ignore the opinion polls entirely, he would simply present himself to the voters, and they would decide.

Texas' Favourite Son, Governor John Connally, at the 1968 Democratic National Convention with his delegation.

Richard Nixon was in the midst of the greatest political comeback in American history. Having previously served two terms as vice president as the running mate of President Dwight Eisenhower, Nixon had narrowly lost the presidency to Jack Kennedy in the Election of 1960. Attempting to regain his footing, in 1962, Nixon ran for Governor of California, where he went down in embarrassing defeat to the incumbent Democrat. Declaring, “You won't have Dick Nixon to kick around anymore,” his political career seemed unquestionably over. However, despite what appeared to be the brutal end of his chances for elected office, Nixon remained quietly involved in Republican affairs. In the 1964 Republican primary, Nixon discreetly tried to position himself as a compromise candidate between the party’s conservatives, represented by Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona, and the party’s moderate-liberal Eastern Establishment, represented by Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York. Although Goldwater had been able to quickly secure the nomination at the 1964 Republican National Convention, the bitter infighting and Goldwater’s fringe positions paved the way for Lyndon Johnson’s crushing landslide victory, but, it also left an opportunity for an uncontroversial figure to step in and unify the party. Nixon, who had since moved to New York to work for the prestigious legal firm Nixon Mudge Rose Guthrie & Alexander (with himself as the newly added titular Nixon), used his new connections in New York law to hire an inexperienced but enthusiastic and innovative new staff to prepare for a presidential run in 1968. Prominently campaigning for many Republicans during the 1966 midterm elections, Nixon had established himself as the man to beat for the Republican nomination. His only clear opponent had been Governor George Romney of Michigan, a Rockefeller-backed member of the Eastern Establishment. However, under intense media scrutiny, Romney’s campaign self-destructed before the primaries had even begun, after a gaffe where he remarked he had been “brainwashed” into supporting the Vietnam War, as well as a statement by Rockefeller indicating that he would be entering the race himself. In the aftermath, Romney withdrew. However, Rockefeller, unsure of his chances, denied that he would be running, leaving Nixon unopposed in the primaries. By the time Rockefeller formally announced, Nixon had already swept the primaries, and many delegates who might have otherwise supported him were already committed. On the other end of the party was Governor of California Ronald Reagan. Formerly an actor, Reagan had laid the foundations for his political career by vocally supporting Goldwater in 1964, and had swept into office in a landslide in 1966, in part because of Nixon’s midterm campaigning [5]. Laying claim to the conservative wing of the party, Reagan was equally hesitant to attempt to directly challenge Nixon, for fear that it would cause a split similar to 1964. As the convention opened in Miami Beach on August 5th, Nixon deftly played the two wings of the party off of each other; by stoking fears of a Rockefeller nomination, he was able to gain the support of conservative Republicans such as Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina and Barry Goldwater himself, both of whom would otherwise have supported Reagan. Additionally, by presenting himself as the guaranteed, uncontroversial, inevitable winner of both the nomination and the election to come, Nixon was able to hold enough support with delegates from the Midwest and Mid-Atlantic who might otherwise have supported Rockefeller. With this deft political manoeuvring, Nixon was able to narrowly win the nomination on the first ballot. Wishing to keep things as simple as possible, decided to choose a non-entity as his vice president, in the form of Governor of Maryland Spiro Agnew. Agnew had previously been one of Rockefeller’s most fervent supporters, but Rockefeller’s earlier declaration of non-candidacy embarrassed Agnew, who had boldly declared Rockefeller’s imminent candidacy, and had brought several reporters into his office to watch the 'campaign launch,' only for him to declare he was not a candidate. Agnew had then switched his loyalties to Nixon, and had secured the Maryland delegation for him during the nominating process. Nixon believed that the moderate, unknown Agnew would be a safe choice as his running mate.

Once nominated, Nixon prepared to implement the strategy he had been setting up for years. As far back as 1966, Nixon had been specifically planning on running against Johnson in 1968. To that end, he had spent his time out of office cultivating an image as a respected elder statesman, providing very public 'helpful' criticism of the President. Always waiting for a moment of weakness, Nixon would tut and wag his finger at every setback in Vietnam, riot in the streets, or unpopular economic decision. Presenting himself as above the fray and an experienced administrator, Nixon hoped to make his core demographics the traditional Republican voters of rural areas and suburbia, as well as expand into those demographics in the South, where they had traditionally voted Democratic. In order to garner the support of the South and middle America, Nixon adopted a vague, mild-mannered opposition to social disorder, crime, government overreach, and Johnson's handling of the Vietnam War. He promised he would not support school busing desegregation, and pledged to appoint less “activist” judges to the Supreme Court. The latter point was a reference to the judicial activism of Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren. The Warren Court had been one of the most famously liberal in American history, making landmark decisions on civil rights, criminal procedure, the separation of church and state, and other issues. With Warren himself retiring, there was an opportunity for whoever won the election to appoint a new Chief Justice and redefine the courts. Nixon's call for judges who would more strictly adhere to the Constitution carried the implication that judicial appointments under a Nixon Administration would at least slow the nation's rapidly accelerating social progress. However, as part of his centre-right strategy, Nixon conceded the traditional Democratic demographics of the Midwest and Mid-Atlantic, namely, urban, ethnic, unionized, and black voters. Believing that his plea to the “forgotten American” implicitly included middle class unionized and black voters, Nixon made no special effort to try and win them over. As for Vietnam, Nixon nebulously promised “peace with honor,” and questioned the means by which the war was being fought, but not the ultimate goal of a negotiated peace that would ensure South Vietnam's continued existence. Although surprised by McCarthy's nomination, Nixon did not change his strategy, believing that McCarthy would not be able to overcome the fundamental differences within the Democratic Party. Nixon's chief concern, at least for the time being, was the populist upstart campaign of former Governor of Alabama George Wallace.

"Nixon's the One." Visiting Chicago shortly after the Democratic National Convention, Nixon emphasized his law and order credentials, and drew up to four hundred thousand attendees.

George Wallace had gained infamy when, in his inaugural address as Governor of Alabama in 1963, he had declared that there would be “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” Wallace’s political origins had begun in the 1958 Alabama gubernatorial election. Running as a Democrat in what was at the time a one-party Democratic state, he had earned a reputation as a moderate by Alabaman standards by supporting racial segregation but opposing the Ku Klux Klan. Losing in the Democratic primary to his overtly racist and pro-Klan opponent, Attorney General of Alabama John Patterson, Wallace vowed to never be “out-niggered” again. In the intervening years, Wallace carefully crafted a reputation as an ardent opponent of desegregation, and mixed the issue in with a right-populist brew of opposition to communists, liberal eggheads, stuck-up federal bureaucrats, sanctimonious Washington judges, and black provocateurs out to destroy the Southern way of life. Although campaigning focused almost entirely on social issues, Wallace also included a moderate economic course of low taxes, fiscal responsibility, and make-work projects. With nearly the exact same percentage of the vote that Patterson had gotten in 1958, Wallace defeated his more moderate opponent in the Democratic primary, and went on to win in the general election with ninety-six percent of the vote. Once governor, Wallace engaged in a series of grand-standing confrontations with the federal government as it tried to enforce desegregation, most infamously in his ‘Stand in the Schoolhouse Door,’ where he physically put himself between the University of Alabama and two new black students attempting to register, with their entry ultimately being enforced through an executive order by President Kennedy.

As 1964 approached, Wallace began to prepare for a primary challenge against Kennedy, beginning a nationwide speaking tour where he praised states’ rights and local governance, and denouncing what he called federal overreach. Wallace believed that as a Southern right-populist, he would be the perfect foil to the liberal Catholic President. Ignoring the obvious implications of advocating for states’ rights at a time when many states where doing everything in their power to interfere with federal civil rights legislation and court rulings, Wallace denied that he was racist, or had ever intentionally appealed to racism to boost his political career. Instead, he blamed racial unrest on corrupt politicians and communist activists ‘tricking’ the black population of the South with “false promises of a utopia,” and that, “The Negro has not received any ill-treatment in the South.” To anyone familiar with segregation, Wallace was obviously lying. As Governor, he had organized brutal crackdowns of civil rights demonstrators by using the Alabama Highway Patrol, run by his henchman Albert J. Lingo, as his own security force. Additionally, through a quid pro quo network of extremist supporters in the Ku Klux Klan and National States’ Rights Party, he had a handful of radicals willing to engage in terrorist attacks on his behalf [6].

Throughout 1964, Wallace preyed on ingrained racial fears amongst America’s white populous. He frequently and falsely claimed that the Civil Rights Act would result in the government seizing white suburban homes to give to black people, and would give black citizens special legal treatment over anyone else. Even after President Kennedy was assassinated, Wallace decided to go through with his primary challenge against the new President Johnson. Putting up a rhetorical smokescreen, Wallace would dodge the most controversial or pointed questions sent his way with a disarming joke, and would always couch his language in the terms of small government rather than in the rhetoric of overt racism. Running against a trio of favourite sons, Wallace would ultimately get around thirty-three percent of the vote in the Wisconsin primary, slightly under thirty percent in the Indiana primary, and forty-three percent in the Maryland primary. Wallace exceeded all expectations of his chances in the Midwest, and won an outright majority of white voters in Maryland. Wallace’s core demographic outside of the South had been white lower middle class suburban voters, who were typically first or second generation Americans. Being from the lower income suburbs closest to urban centres with high black populations, the ‘Wallace vote’ had been those white voters who most directly felt the growing prosperity of the black community, as they began to move into the same lower middle class suburbs as them. The Wallace vote’s economic anxiety became inseparable from their inherently racist beliefs that black neighbours would threaten their jobs, lower their property values, increase crime, and decrease the quality of local schools.

Running under the banner of the American Independent Party, Wallace had returned in 1968, and enjoyed enough support nationwide to appear on the ballot in all fifty states. Sticking to the performance that he had been refining for nine years, Wallace distanced himself from overt segregationism, and relied more and more on dog whistle racism. Running a robust 'law and order' campaign in which he vilified student protestors, anti-war activists, and black Power advocates as a gang of communists and criminals given protection by a godless, overly-permissive federal government. 'Vote for George Wallace,' he seemed to say, 'and the government will finally look after the little guy, the responsible citizen, and do away with all the kooks and crazies.' Similarly sticking to bread and butter economic issues, Wallace promised lower taxes and smaller government. On Vietnam, he was simultaneously the most dovish and hawkish of the three major candidates, as he promised to give the military's Joint Chiefs of Staff complete control of the war effort, and if they could not win in sixty days, he would have America unilaterally withdraw. Wallace's base remained largely confined to rural and lower middle class voters, but with a nationwide audience and social anxiety at an all time high, he garnered massive support from unionized workers in the Midwest, and reached nearly twenty percent in the polls, and threatened to deadlock the Electoral College, preventing any clear winner [7].

"Stand Up For America." George Wallace shakes hands at a rally. Preying on social and racial anxiety, Wallace led a potent, populist campaign in 1968.

It was in this tumultuous political environment that the McCarthy campaign found itself adrift. McCarthy held to the same positions he always had, and waited for the electorate to come to him. He continued to refuse to make any serious campaign decisions, and remained reliant on his staff and state volunteers to prepare events for him. He continued to advocate for a negotiated settlement in Vietnam that would include a complete bombing halt and democratic elections in which the National Liberation Front would be allowed to participate. On the economy, his chief proposals remained a universal basic income proposal, and the implementation of the findings of the Kerner Commission, which called for a dramatic increase in social security and welfare spending. McCarthy did not avoid his policy positions, but his natural inclination to meandering and philosophical speeches obfuscated the issues, as he focused on the nature of America and its institutions. McCarthy called for a more limited role for the president, a restoration of America's societal-moral fabric, and a calm, reflective analysis of the issues facing the country. None of McCarthy's policy proposals were particular popular, but his own popularity did not seem to be tied to theirs; a majority of Americans held a positive opinion of him, he was especially liked by independents, and had significant Republican crossover appeal. Ironically, during the Democratic primaries, he had performed weakest among Democrats, who consistently preferred Kennedy or Humphrey to him. His strongest demographic, the suburban middle class, had, in large part during the primaries, been Republican and independent cross-over voters.

With McCarthy's quixotic appeal, his chances of victory would be entirely determined by turnout. The greatest battle between Nixon and McCarthy would be over the suburban middle class, with the traditional Democratic demographics on the periphery. If McCarthy failed to rally the traditional Democratic demographics and trigger a large turnout, it would undermine his percentages enough that his popularity with the middle class would be irrelevant. Alternatively, the same result could have been reached if Nixon had made any concerted effort to win over voters in the traditionally Democratic demographics.

"Let Us Begin Anew." McCarthy greets a packed arena in the Midwest. The final outcome of the Election of 1968 would be determined by McCarthy's ability to effect turnout.