You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The March of Time - 20th Century History

- Thread starter Karelian

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 336 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 316: Feuds and fundamentalists Chapter 317: The Shammar-Saudi Struggle Chapter 318: Arabian Nights Chapter 319: The Gulf and the Globe Chapter 320: House of Cards, Reshuffled Chapter 321: Pearls of the Orient Chapter 322: A Pearl of Wisdom Chapter 323: "The ink of the scholar's pen is holier than the blood of a martyr."This link appears to be very much related to Current Politics.Graphic resources:

MOD EDIT

Please only post this sort of, quite interesting, information in Chat Threads.

Chapter 146: The Abdication Crisis, Part II: Noblesse oblige

The court of Wilhelm II was the centerpiece of a vast administrative apparatus: The Ministry of the Household as well as the Civil, Military and Naval Cabinets. In addition, his General Adjutants and Flügeadjutants had been constantly there to offer their council to him at every opportunity and for every matter. Hand-picked and elevated to their role by Wilhelm, they were the first ones to see their positions crumble by the sudden dramatic development of the Eulenburg Scandal. As a court mostly consisting of amusing flatterers and shameless yes-men had done their best to avoid all disputed and difficult issues, this system had in retrospect long since been primed to collapse at the first major setback.

Eulenburg had managed to keep the Reichstag in order and navigated German foreign policy cautiously enough to avoid major crises, but when he fell, his elaborate arrangement of social and political networks came crashing down hard. “To have kept the coach from overturning for so long, and to have skirted such abysses, was a service to be grateful for", remarked Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, the Imperial State Secretary for the Interior in a private letter.

The whole government of Prussia and the Reich were tied to the throne of the German Kaiser. But as it turned out, his actual person was not a fundamental and irreplaceable piece in the system, even though many had thought so just days before. The November days that led to the abdication were surreal for all participants, especially to the German public at large.

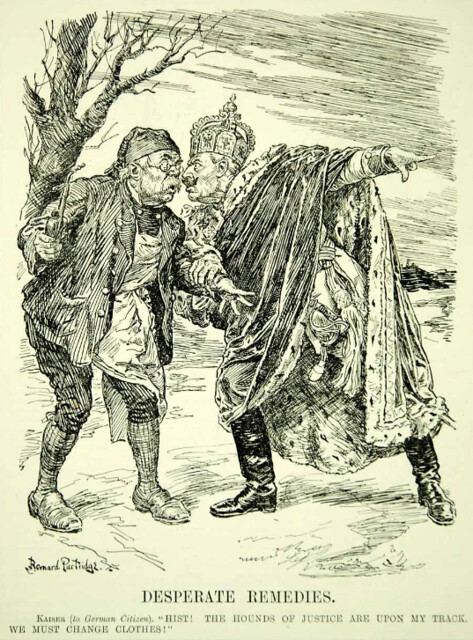

The nation that had officially prided itself as the most submissive and royalist on Earth had now openly defied its sovereign, and claimed redress. The yellow press had been allowed to tear the Emperor to pieces with ridicule and satire, without being torn to pieces themselves by the previously impervious censorship system.

On 10th of November the Reichstag met, with the appearance of a national court of justice against the sovereign. Members of the Federal Council had already envisaged that abdication might be a real possibility, but the mood in the room was still surreal - it was a historical moment, and people felt like anything might happen - solemn pledges, constitutional modifications, oaths of loyalty.

The aristocrats of Bavaria, Saxony, Oldenburg, Württemburg and other federal princes who were assembled in Berlin were talking of rough justice. The rude, vain, philistine, haughty, excessively moralistic and outright boring Emperor had brought them such shame and foreign ridicule!

For years he had treated them as mere vassals, expecting them to do his bidding unquestioningly, even while they too held kingly titles. Prince Regent Luitpold of Bavaria was especially merciless, as he had not forgotten the way the Kaisers Chancellor had treated the Catholics of Southern Germany. Right now, more than ever in decades, the Hohenzollerns were upstarts in the eyes of many of these German princes.

Prince Regent Luitpold had seen enough mad kings for one lifetime,

and utilized the animosity felt towards Wilhelm II among the German upper nobility

to alter the balance of power within the complex political system of the Kaiserreich.

“They grew up overnight”, the head of the very ancient (and entirely unimportant) House of Schwarzburg-Sonderschausen declared. The Wittelsbachs of Bavaria were especially snobbish in this regard, but they were not alone. Marginalized princes and counts who traced their sovereign rights back to the days before the French revolution had loathed him because of Wilhelm’s preference for lower-ranking peerage. The high aristocracy, Hochadel, now reminded their peers that they all had ancestors who had been prominent lords when the Hohenzollerns had been mere knights, and they therefore looked upon Wilhelm II as an equal.

The Reichstag and the Civil Cabinet was well aware of the royal mood. The Diet, wanting to appear relevant in a historical moment, ultimately opted for a rather modest measure, passing a vote of censure for von Moltke with a clear majority. To this von Moltke replied that he was now tendering his resignation, along with the responsible Secretaries of State. When he left to meet Wilhelm II, von Moltke thought that this was how Prince Felix of Schwarzenberg must have felt half a century earlier.

Last edited:

Chapter 147: The Abdication Crisis, Part III: Prodigal Son

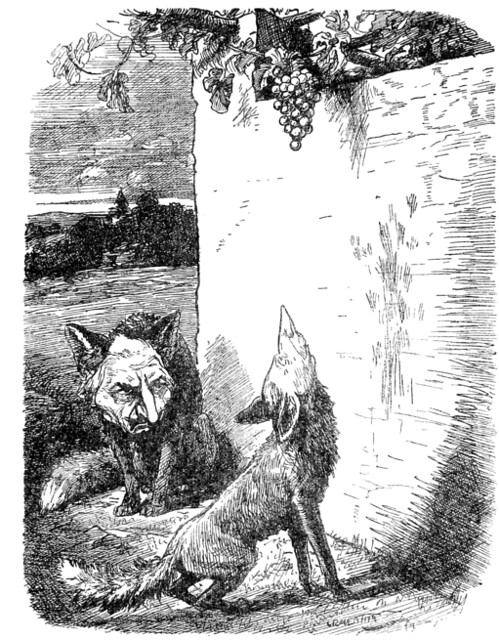

"I do think that they look ripe, so let me try instead."

Hausmarschall Hans v. Gontard, the former tutor of the Crown Prince, was practically considered family and a highly influential figure in the sudden political prominence of Auguste Viktoria. Dona and Gontard had talked a lot about the state of Germany, and the path ahead for young Wilhelm, the man they both had reluctantly decided to elevate to replace his ailing father.

Dona had done all she could for the boy. She had talked Willy out of a disastrous marriage plan, only have him see the light and court and then marry a woman worthy of his status. Cecilie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin had been a fine match for Willy, and their wedding and the following visit to King Edward’s birthday in Britain had allowed Willy to meet his cousins with both public and private displays of bonhomie between the related royal families, despite the stressed relations between the British monarchs and Wilhelm II.[1]

Now the monarchy was struggling, and the elephant in the room seemed to call for an end of the reign of the Hohenzollerns. It was now up to young Willy. The idea shocked Dona. No matter how much she had prayed for his beloved son to succeed and prepared him for this moment, she still felt that it was way too soon for God to put him to test. But then again, everything was relative. His husband had already reigned for twenty years, and he was now fifty, worn down by the burdens of office and his personal struggles and - as it had turned out - sins, vices and lack of judgement.

Zusammenbruch (collapse) had to be averted, of that Dona was dead-certain. And von Gontard consoled her by telling that not all was lost, far from it.The bourgeoisie still felt good about the bright future of Germany. While the middle classes had grown prosperous and were seeing their lot in life improve with every year of the reign of Wilhelm II. The newspaper articles and public displays of dissent held at the Harden rallies were only part of the wider picture.

The royal parades and public speeches and visits still attracted the mass attendance of the middle classes, peasants and tradesmen, even if the Federal Princes and the Junkers aristocracy were by now nearly as opposed to Wilhelm II as the SPD leadership. Police informers in pubs of working-class districts of Hamburg heard some disparaging, but also many supportive and even affectionate comments about “our Wilhelm" caught in the midst of the scandal. The Kaiserin, with her sincere manner and charitable and fundraising activities was still widely regarded as “the most beloved member of the royal family.” Royalism would be wounded and slighted with the abdication, but it was still a strong force in German society.

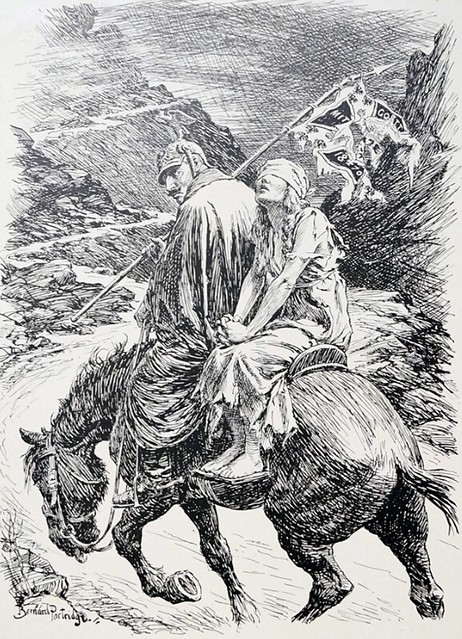

The consultation between the two Cabinets was still ongoing, when the Crown Prince arrived to meet the Kaiserin. His mother, in tears, told him what his duty entailed at this desperate hour. Without her, the Crown Prince himself might not have found the type of courage to seize the rope thrown to him by fate once, and only once. Yes, he would meet the Federal Princes and the Cabinet, swear the oath - and wear the crown.

1: Since relations are less strained than OTL, Wilhelm II allows the meeting to take pass despite his personal reservations.

Last edited:

Chapter 148: The Abdication Crisis, Part IV: Marquis of Carabas

By the time Wilhelm II decided to abdicate, “Crown Prince Willy” had already taken over much of his father’s responsibilities weeks ago. As the future emperor remarked: “He had lost his hope, and felt himself to be deserted by everybody; he was broken down by the catastrophe which had snatched the ground from beneath his feet; his self-confidence and his trust were shattered.”

For a monarch who had always been pampered and shielded from criticism, the latest string of disastrous setbacks had simply been all too much. Wilhelm II had wept when he read the speeches held in the Reichstag, but soon he refused to read nothing more about the whole affair, and he began to seek distraction from his troubled thoughts.

Had he not done all a man and an Emperor could? Had he not ever flinched from the fatigues of distant journeys, that he might forge new bonds of political friendship in person at Rome, Damascus, Athens? The false friends had craftily misguided and surrounded him, the noblest quarry in all Europe, bringing him crashing to his fall.

Rancour of an evil world, envy of kindred royal Houses - no, evil-spirited rivalry of jealous dynasties had broken him down. The misunderstood father of his people, a pacific sovereign misunderstood by his English uncle and his Russian cousin - here he had to stand, the martyr of his own endless good-will, and watch the circle closing round his beloved realm. The ineffable cheek! Pharisees! Rot! Twaddle! Bunkum!

Going through melancholy moods, fits of boiling rage and sense of abandonment and betrayal all at once, Wilhelm II began to slip to his own bubble of unreality. His closest aides began to wonder whether he chose to ignore the facts consciously or whether it was simple duplicity at play. The first response of the Kaiserin was to shield his husband away from further bad news and hardship. She began to rearrange his life in a way that was soon virtually untouched by what was actually happening in Germany. Dona also told her remaining entourage to do their best to prevent any bad news from reaching his ears.

An old cure to his woes, keeping him on the move, was adopted. Loyal to his old moniker, the travelling Kaiser (a common joke of the era was to read the I.R. in his royal signature as Ich Reise) was shipped abroad. He visited old friends in Britain: Viscount Pirrie, Marquess of Ormonde, Earl of Lonsdale and Earl Brassey. He continued his sailing acquaintances with rich Yankees: men like J.P. Morgan and the Vanderbilts, Wanamakers, Armours, Drexels and Goelets were all still eager and willing to meet the one and only, scandalous and famous “Old Kaiser Bill.”

Court hunts were one of the few unofficial occasions where Wilhelm III would appear in public together with his father after his abdication.

He kept up appearances to regattas in Britain during summers, giving the yellow press a constant source of gossip while paying no heed to publicity anymore. During winter he focused almost solely on hunting. He kept up with his old habits, staying two or three days out in the field in a row: twice a week he traveled to Romintern, his favourite estate, while visiting Prince von Pless, Duke Hatzfeldt-Trachenberg and Count von Donnersmarck.

His visits to the United Kingdom also took a different character. Of all of his many cousins in the royal houses of Europe, it was in Britain where the wayward "Margrave of Brandenburg" was met with at least a tiny bit of sympathy. While the British royal family formally kept their distance to their scandalous kin, and no longer associated directly with him outside of major events like funerals or weddings, he was always treated in a most courteous manner. This meant a lot for William, like his personal correspondence from the era clearly shows.

“I found that my parent’s old apartments in Windsor Castle, where I often played as a little boy, had been assigned to me... Manifolds were the memories that filled my heart...They awakened the old sense of being at home here, which attaches me so strongly to this place, and which has made the political aspect of things so personally painful to me, especially in recent years. I am proud to call this place my second home, and to be a member of this royal family...And they had kept my memory green, as a child who was so addicted to pudding that he once was violently sick! Kindest regards.”[1]

For British public, the new popular children’s book of Kenneth Grahame was widely regarded as a direct allegorical reference to the recent events in Germany. And just like in the book, at the end everything and nothing had really changed: Mr. Toad would continue to cause embarrassment and worry to himself and his friends alike, but definitely not out of malice.

1: From an OTL letter.

Driftless

Donor

For British public, the new popular children’s book of Kenneth Grahame was widely regarded as a direct allegorical reference to the recent events in Germany. And just like in the book, at the end everything and nothing had really changed: Mr. Toad would continue to cause embarrassment and worry to himself and his friends alike, but definitely not out of malice.

Mr Toad as an avatar for Kaiser Wilhem II. I did not see that coming, but it works, in this circumstance !

You capture Wilhelm quite well. He was a fundamentally pathetic person, who might have been quite sympathetic had his position not been such that his vanities and neuroses affected so many millions.

It has been used by several other authors before me. Personally I like the comparison a lot: an irritating and completely irresponsible, but definitively not malevolent character.Mr Toad as an avatar for Kaiser Wilhem II. I did not see that coming, but it works, in this circumstance !

He's still more than capable of making life really difficult for many people, his son and family included.You capture Wilhelm quite well. He was a fundamentally pathetic person, who might have been quite sympathetic had his position not been such that his vanities and neuroses affected so many millions.

I've reached post #220 so far - what an awesome Timeline! Well-deserved Turtledove nomination. An excellent and knowledgeable Panorama of the period and very interesting and plausible divergences!

I've reached post #220 so far - what an awesome Timeline! Well-deserved Turtledove nomination. An excellent and knowledgeable Panorama of the period and very interesting and plausible divergences!

Thanks for the feedback. The first chapters from seven years ago show that proof-reading software back then was far from the modern standards.

But since the read-only document of this timeline (with pictures) currently has 640 pages, I haven't really found time to edit and proof-read them to meet my current criteria.

Portugal and Spain will both eventually feature in this TL, but right now the European royalty (and this TL) will focus their attention to Germany, for obvious reasons.Will the assassination of the King Carlos I of Portugal and of his son and heir Luís Filipe be avoided ITTL?

Just finished reading through all of this. An incredibly well-written, thoroughly researched, and in-depth timeline. I must say it is the first time on this site where I have seen a narrative written so in-depth and still interesting, despite the relatively slow pace. As someone highly interested in the Belle Epoque/Fin de Siecle period, I'm eager to see where you will take this timeline @Karelian!

Thanks for the compliment. The style I've chosen is definitively not for everyone's taste, but I'm glad to hear you liked it.Just finished reading through all of this. An incredibly well-written, thoroughly researched, and in-depth timeline. I must say it is the first time on this site where I have seen a narrative written so in-depth and still interesting, despite the relatively slow pace. As someone highly interested in the Belle Epoque/Fin de Siecle period, I'm eager to see where you will take this timeline @Karelian!

The drawback of research-focused method is that I tend to hoard an awful lot of source material, read it through while writing lot of notes that will ultimately form the basis of the actual upgrades.

What is the fate of Swedes in Russia, now that the two states are on the brink of conflict?

Good question. Grand Duchy of Finland will definitively be affected by the events on the other shore of the Gulf of Bothnia, but I'll deal with that in detail once the situation in Germany is covered first.What is the fate of Swedes in Russia, now that the two states are on the brink of conflict?

Chapter 149: The Abdication Crisis, Part V: This is the House Wilhelm built

By the time the Eulenburg scandal turned into a crisis of abdication, an oligarchy of some twenty individuals held positions of real official power within the highest ranks of the German Empire. They controlled appointments, legislature, and sought to determine internal and foreign policy as well. Ministry of the Household, the Civil, Military and Naval Cabinets, General Adjutants and Flügeadjutanten, the Liebenberg circle of Eulenburg, influential friends like Messrs Krupp, Stumm, Henckel, Ballin - all ready to offer advice, each one one of them elevated to their current official or unofficial position primary because of their ability to get along with the All-Highest Person.

As the Liebenberg circle dispersed and collapsed during the trials, the importance of the legal and official system centered around Wilhelm II grew. The official court administration started from the Cabinet chiefs - Civilian, Military and Naval. From them, the administration extended outwards to the seven Prussian Ministers, the Chancellor, the head of the Reich Chancellery and the State Secretaries of the six Reich Offices. One had to also take account the imperial Flügeadjutants of the maison militaire, the Headquarters of His Majesty the Kaiser and King. They too had controlled the access to the Kaiser, and especially the ones stationed to Berlin or Potsdam had made a habit of meddling in court politics. Wilhelm II had started with a twenty-men strong military entourage, and the ranks of this group had risen to 33 by 1905.

These men had much in common. All of them were in their mid-40s. Sons of landed squires and officers from east of Elbe, these men had climbed the traditional ladder of Junkers society: cadet school at Lichterfelde, service at the same regiment their fathers had served before them, then to the War Academy, where the ones with best contacts and most talents were picked up to the General Staff. They belonged either to the old nobility or to the new titled peerage, and the majority of them could trace their ancestry to the houses that had served Frederick the Great in the 1700s. These von Kleists, von Zieterwitzs, von Bonins, von Puttkamers and von Kemekes all knew one another and many had family connections as wells.

Decisions inside this system could be done either by deferring to the judgment of one of them or collectively. Or, as it quickly became obvious in November 1908, they could not be done at all, at least in time. When everyone was trying to save themselves from the scandal-focused newspaper headlines while also seeking to persuade their beleaguered Kaiser to stand firm and hold his throne, the system would have required a firm chancellor to take the reins and restore control of the chaotic situation. Unfortunately this stress was too much for the hapless von Moltke, who was not up to that task. For the other major actors in German society, this was a moment of self-reflection and a call for action.

Chapter 150: The Abdication Crisis, Part VI: The Man who Would be Kaiser

Crown Prince Wilhelm and lieutenant von von Mitzlaff (at left.) Men like him suddenly gained new influence in 1908.

Wilhelm II had liked to think of himself as a personification of the Empire, but in his shadow and headline-filling flow of public speeches and statements a complex federal structure and numerous political factions made things more complex and fragile than many foreign observers realized. In many cases he had really been the supreme leader he had wanted to be, behind the facade of tractability and vanity. Chancellor Eulenburg had retained influence, more than anyone before, but even he had been next to helpless to oppose the pet projects of Wilhelm II. Wilhelm II had dictated policy; bills, diplomatic moves, and all appointments had been confirmed by him, with the responsible Government being in a constant state of flux and disarray, with ministers coming and going.

At the background the Bismarck-era compromises that held Germany together were all balancing acts supporting one another. The whole system rested on the foundation of loyalty to the Kaiser and to the regional dynasties, supported by Prussian illiberal authoritarianism. For the last few decades the various political traditions of the smaller constituencies and the question of parliamentarism and democracy vs. the monarchical reign of Wilhelm II had both been issues that the government had rather avoided than confronted.

In thruth there were still many Germanies within the framework of the Kaiserreich. Did the German Empire really meant a Prussian-dominated federal state (Bundesstaat), or a confederation of states (Staatenbund)? Was the Kaiser was simply primus inter pares of the German Fürstenbund? After all, had it not been a Bavarian King who had formally invited the King of Prussia to accept the imperial title? The individual sovereignty of the member states and their monarchs had been enshrined to the Constitution of 1871, when 25 political entities from Prussia to Schaumburg-Lippe had joined forces through the Bundesrat.

And what of the man who would have to inherit this mess?

In October 1907 he was finally attached to the bureau of the Lord Lieutenant at Potsdam, to the Home Office, to the Exchequer, and to the Admiralty. But instead of being initiated to the questions of German foreign policy, he had been instructed to attend lectures on machine construction and electronics at the University of Technology at Charlottenburg. His study friends had found him charismatic, aristocratic, debonair - but also shallow, irresponsible, and a womanizer to boot. Out in public he was as a rule amiable, with pleasant manners.

No one really disliked the Crown Prince in 1908, but most who knew him thought him a fool who lacked the dignity of his father. He had so far failed to show serious interest in anything, liked to make a joke of questions and matters discussed, and bored easily. Many senior members of the court elites had dismissed him as superficial, vain and without any thorough knowledge of anything. Here they strongly parroted the views of his father who had always viewed him as lazy, foppish and undisciplined.

One of his main traits was a strong dislike of fusty formalism. After years of a bored royal teenager forced to attend the vainglorious festivities of Wilhelmine court, he detested everything courtly, pompous or decorative, and had suppressed all formalities in his own circle as far as was feasible. The Crown Prince preferred to associate himself with with artists, authors, sportsmen, merchants and manufacturers rather than elder members of fellow nobility. Sports and hunting were his way to pass the time and get along with his future subjects. Much to the dismay of the court (and largely because of it, no doubt)he had used to attend bicycle races, football matches, route marches and other sporting events at every turn, promoting them by the presentation of prizes.

He had only three good friends: Count Finckenstein, von Wedel and von Mitzlaff - all lieutenants of his age from his old unit. The surnames told a lot about the company he preferred: von Fickensteins were Uradel, dating their roots back to the 12th century Carinthia.

His view towards older people and court in general was thus firmly established by 1908.

But the Crown Prince, just like his father, was easily swayed to one direction or another. He held King Edward of Great Britain in high regard because the old king had always been extremely friendly to him and had met him several times - another thing that most likely stemmed from his desire to oppose the domineering nurture of his father and the rapid anglophobia of his mother. The dualistic pull of German imperialism and the respect of his British cousins had tormented his father to no end. For the Crown Prince, this internal conflict was much less visible and stressed, but nevertheless formed another aspect of his personality that had most outsiders had described as bland and rather boring before 1908.

Chapter 151: The Abdication Crisis, Part VII:"Mit der Krönung der Kronprinz wird das alles in Ordnung kommen"

“This is the end; and the only question is whether we will have the courage to perform the operation, or whether we prefer the slow decomposition of the body of the Reich.”

Harden regarding the rumours of abdication in November 1908.

Forces of order and forces of change had contested the politics of German Empire from the beginning, and the abdication crisis led both sides of this old struggle to the old political battlefields. The Junkers, industrialists, higher bureaucracy and the army were once again at odds with liberals and socialists. Bismarck had controlled this permanent dilemma of German politics with a mixture of war, reform and state building. Playing up tensions with France or Russia had enabled the Iron Chancellor to win Reichstag majorities for pro-regime parties time and time again. Holstein was on point when he dryly remarked that reactionary governments always attempted to divert the internal struggle to the foreign sphere. Half a century earlier the conservatives had wanted order abroad and order at home, while the liberals had wanted a revolution that would sweep away old Europe both at home and abroad. Bismark had squared the circle by enforcing order at home while at the same time pursuing a radical foreign policy abroad.

Much - and little - had changed since then. The conservative nationalists were still urging their countrymen to strive for “pure heights of German idealism” and “pure Germandom” in the struggle against socialism, cosmopolitanism, confessional and class antagonisms, materialism and trivialization - that is, modernity. The monuments and celebrations so cherished by Wilhelm II had been a call to mobilize the conservative middle class to a war against “the forces without Fatherland.” But as much as the East Elbian Junkers, industry barons of Westphalia and the conservative members of the middle stratum confessed their desire to fight anything and everything that seemed to bring about democratization or liberalization of society, they disagreed on the methods.

By 1900 it was clear that repression policies against the Social Democrats had failed, and only two options remained. Either a gradual de-escalation and acceptance of new normal, or a full-scale military and police action combined with abolition of civil rights, as Bismarck had envisioned before his downfall in 1890. Yet the Subversion Bill had never passed. Day to day government remained in civilian rather than military hands. The Kaiser and the conservatives had talked tough, but stopped to their legal limits. The Social Democrats had so far responded in kind. Now fear of a scenario where a detachment of armed guards might descend on the Reichstag, send the deputies packing, arrest any dissidents, and shut down the opposition newspapers was real among the middle classes and socialists alike.

After all, the Wilhelmine era had been a determined re-assert the power of the emperor from the start. Caprivi had witnessed the decline of the authority of the chancellorship, with forthright declarations, and disagreements and the fractious behaviour of the Reichstag and the undirected, vague and bombastik “Weltpolitik." This clumsy opportunism of late Hohenlohe years was replaced by the overly cautious status quo project of Eulenburg. In retrospect his foreign policy was doomed from the outset, since the old calculability of the Bismarckian era had been replaced by the jumpy and unpredictable whims of Wilhelm II.

Still, Eulenburg did his best to make sure that Wilhelm’s wishes were could be met in politically manageable realities, with mixed results. The main goal upholding the power and dignity of the Hohenzollern dynasty had met a scandalous end, and the Weltgeltung towards a place in the sun had so far been a rocky road. Acquisitions and influence sought from all corners of the globe had so far met best success in the Ottoman Empire and China, while it had been more luck than skill that had prevented Germany from ruffing off too many feathers in Britain, increasingly irked about the German naval expansion.

The cost of the less-than disastrous foreign policy of the Eulenburg Chancellorship had been unambitious domestic policy, focusing solely on promoting the cause of the personal monarchy of Wilhelm II, while ever-changing combinations of Sammlungspolitik had so far managed to keep the Social Democratic challenge at bay. Picking up from where he left, von Moltke had been almost immediately entangled in the scandal involving his sovereign and his predecessor. Thus he had been unable to do much of anything regarding the pressing economical and political questions of the day. The downfall of two chancellors in a row and the abdication of Wilhelm II marked an end of an era and outright forced new political and economical questions, both foreign and domestic, to the agenda.

Harden regarding the rumours of abdication in November 1908.

Forces of order and forces of change had contested the politics of German Empire from the beginning, and the abdication crisis led both sides of this old struggle to the old political battlefields. The Junkers, industrialists, higher bureaucracy and the army were once again at odds with liberals and socialists. Bismarck had controlled this permanent dilemma of German politics with a mixture of war, reform and state building. Playing up tensions with France or Russia had enabled the Iron Chancellor to win Reichstag majorities for pro-regime parties time and time again. Holstein was on point when he dryly remarked that reactionary governments always attempted to divert the internal struggle to the foreign sphere. Half a century earlier the conservatives had wanted order abroad and order at home, while the liberals had wanted a revolution that would sweep away old Europe both at home and abroad. Bismark had squared the circle by enforcing order at home while at the same time pursuing a radical foreign policy abroad.

Much - and little - had changed since then. The conservative nationalists were still urging their countrymen to strive for “pure heights of German idealism” and “pure Germandom” in the struggle against socialism, cosmopolitanism, confessional and class antagonisms, materialism and trivialization - that is, modernity. The monuments and celebrations so cherished by Wilhelm II had been a call to mobilize the conservative middle class to a war against “the forces without Fatherland.” But as much as the East Elbian Junkers, industry barons of Westphalia and the conservative members of the middle stratum confessed their desire to fight anything and everything that seemed to bring about democratization or liberalization of society, they disagreed on the methods.

By 1900 it was clear that repression policies against the Social Democrats had failed, and only two options remained. Either a gradual de-escalation and acceptance of new normal, or a full-scale military and police action combined with abolition of civil rights, as Bismarck had envisioned before his downfall in 1890. Yet the Subversion Bill had never passed. Day to day government remained in civilian rather than military hands. The Kaiser and the conservatives had talked tough, but stopped to their legal limits. The Social Democrats had so far responded in kind. Now fear of a scenario where a detachment of armed guards might descend on the Reichstag, send the deputies packing, arrest any dissidents, and shut down the opposition newspapers was real among the middle classes and socialists alike.

After all, the Wilhelmine era had been a determined re-assert the power of the emperor from the start. Caprivi had witnessed the decline of the authority of the chancellorship, with forthright declarations, and disagreements and the fractious behaviour of the Reichstag and the undirected, vague and bombastik “Weltpolitik." This clumsy opportunism of late Hohenlohe years was replaced by the overly cautious status quo project of Eulenburg. In retrospect his foreign policy was doomed from the outset, since the old calculability of the Bismarckian era had been replaced by the jumpy and unpredictable whims of Wilhelm II.

Still, Eulenburg did his best to make sure that Wilhelm’s wishes were could be met in politically manageable realities, with mixed results. The main goal upholding the power and dignity of the Hohenzollern dynasty had met a scandalous end, and the Weltgeltung towards a place in the sun had so far been a rocky road. Acquisitions and influence sought from all corners of the globe had so far met best success in the Ottoman Empire and China, while it had been more luck than skill that had prevented Germany from ruffing off too many feathers in Britain, increasingly irked about the German naval expansion.

The cost of the less-than disastrous foreign policy of the Eulenburg Chancellorship had been unambitious domestic policy, focusing solely on promoting the cause of the personal monarchy of Wilhelm II, while ever-changing combinations of Sammlungspolitik had so far managed to keep the Social Democratic challenge at bay. Picking up from where he left, von Moltke had been almost immediately entangled in the scandal involving his sovereign and his predecessor. Thus he had been unable to do much of anything regarding the pressing economical and political questions of the day. The downfall of two chancellors in a row and the abdication of Wilhelm II marked an end of an era and outright forced new political and economical questions, both foreign and domestic, to the agenda.

Chapter 152: The Abdication Crisis, Part VIII: Reshuffling the Reichstag - Black and Blue

- "Outwardly a confident and successful demeanor along with the greatest skill in avoiding a war, and inwardly a moderate conservative government with liberal and social reforms as is today essential to avoid a sudden upheaval, that was the signature of your politics..."

Quote from a letter sent to von Eulenburg in late 1908.

- "I do not underestimate the great talents which, in the most difficult circumstances, enabled Prince Eulenburg, time and again, to bridge over rifts, to effect compromises and adjustments, and to disguise fissures. But he was not a great architect, he was not a man of Bismarck’s mighty mould. He was not a Faust with eyes fixed on the heights and the far horizon. He was a brilliant master of little remedies with which a man may save himself from an evil today for a possibility more bearable one tomorrow. He was a serious politician who had thoroughly learned his craft and exercised it with graceful ease. Firm in the possession of this, he was therefore no charlatan..."

From memoirs of Wilhelm III

On the surface it seemed that middle class liberals and socialists would now be poised to take over from the old elites. Liberalism in Germany was on the rise right after the Abdication Crisis. The left liberals formed a unified Fortschrittspartei, the German Progressive Party, and even the National Liberals moved left as a result of the events of 1908. Yet they still shunned SPD on many key questions, preventing wider cooperation and formation of a credible alternative to the status quo. Plans for a “Bassermann to Bebel”-type liberal-Social Democrat coalition named after the party leaders were unrealistic. Bebel had to pay heed to the left wing of SPD, while Bassermann knew that when it came to asking their supporters to cast their votes for a SPD candidate on the second ballot, their key voters at the big cities would still often prefer bourgeois solidarity over political strategy.

Meanwhile National Liberals were questioning the close relationship the party had with the Conservatives. Out of the fear of the new German Progressive Party that witnessed the union of the three previous smaller left-liberal political groups, the National Liberals steered their party towards anti-agrarian direction, terminating any prospects of a long-term cooperation with their former Conservative coalition partners in the Eulenburg Bloc. Recognizing the need for publicly funded social services, liberalism in Germany was in general becoming more reformist. Only a minority of the left-liberal fringe supported any long-term cooperation with the Social Democrats, as only a few National Liberal and Social Democratic outsiders were prepared to take the idea of a “social-liberal bloc” seriously. There was no potentially majoritarian party constellation that could have replaced the shattered Eulenburg Bloc.

The new Black-Blue block of reactionary conservatives and clerical deputies of Conservatives and Zentrum formed the foundation of the politics after the downfall of the Eulenburg coalition, and they were the force that still held the reins in November 1908. There simply was no parliamentary majority prepared to either uphold or even to aspire for parliamentary rule, and such a move would have in any case stopped to the Federal Council by a Prussian veto. The high bureaucracy, notable Junkers, the army and the Hohenzollern dynasty itself were all resolved to defend their power and interests, even if Wilhelm II himself had had a loss of heart.

Conservatives were dead-set on defending the status quo. Meanwhile Zentrum saw many practical advantages in its policy of shifting alliances, and the party leadership had no intention of committing themselves to dependence on any kind of formal coalition. The Zentrum was a kingmaker party, limiting the gains of SPD among the Catholic working class, but still allying itself with the Conservatives in the Reichstag at many key questions. Free Conservatives and National Liberals were also seeking to solely preserve constitutional rule. Thus the conservative and moderate forces in German politics created the post-abdication reality of German politics more by sheer inertia rather than with determined and active policy of their own.

Threadmarks

View all 336 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 316: Feuds and fundamentalists Chapter 317: The Shammar-Saudi Struggle Chapter 318: Arabian Nights Chapter 319: The Gulf and the Globe Chapter 320: House of Cards, Reshuffled Chapter 321: Pearls of the Orient Chapter 322: A Pearl of Wisdom Chapter 323: "The ink of the scholar's pen is holier than the blood of a martyr."

Share: