Chapter Twenty Six: The Hazen Presidency and the Gordon Presidency Part Two

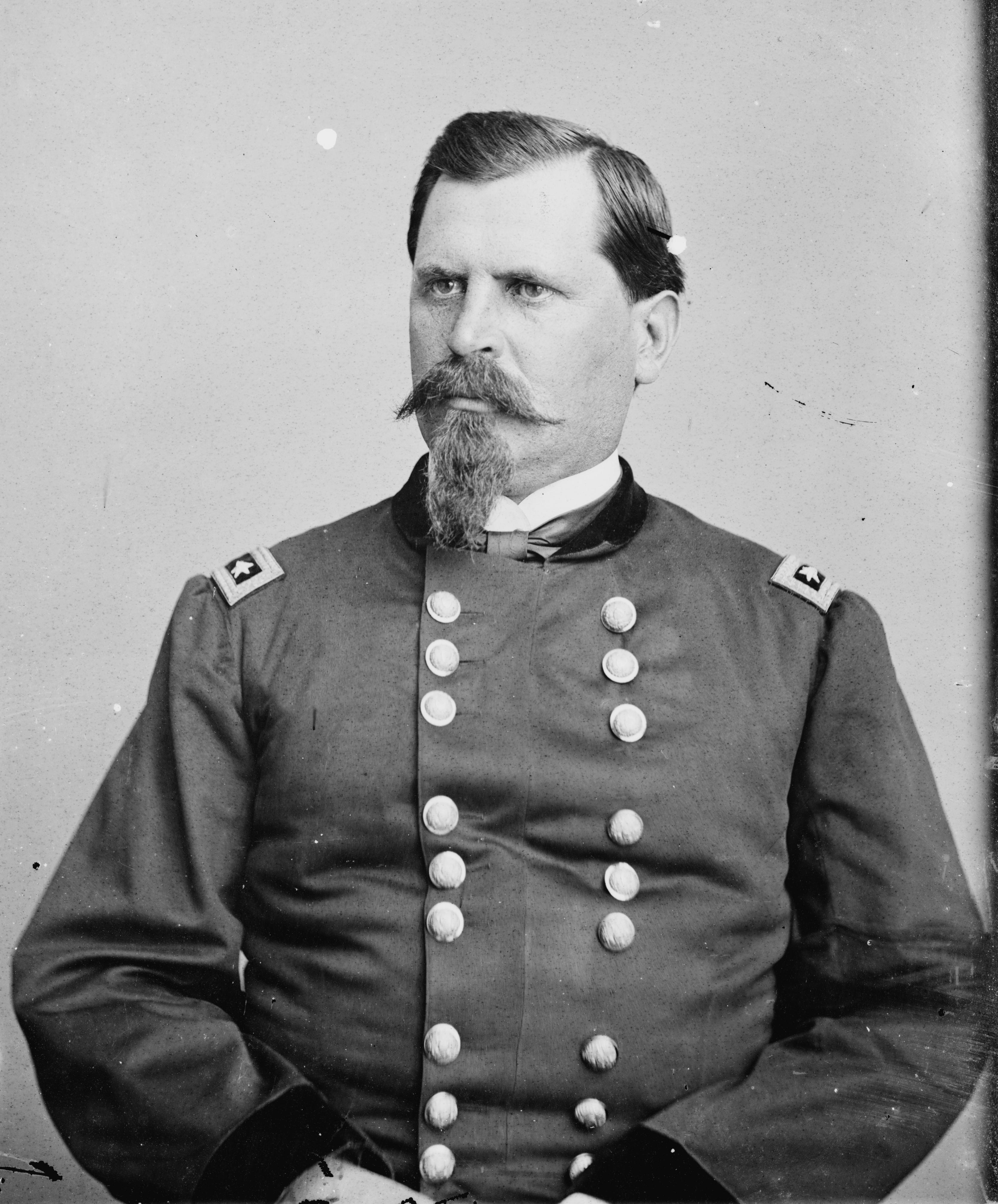

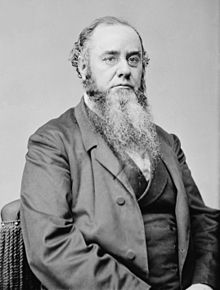

President William B. Hazen

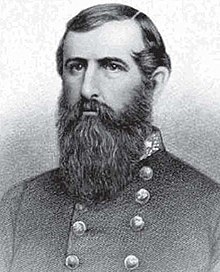

With the election of Hazen, it marked the rise of two things. First was the foreseeable conclusion, which was the return of the Republican Party to power, with Rutherford B. Hayes being elected Speaker of the House, David Davis being elected President of the Senate after a stiff contest with Roscoe Conkling, Oliver Morton receiving the position of Chairman of the House Ways and Mean Committee, and the four Republican leaders most responsible for his nomination, Blaine, Edmunds, Dawes, and Logan, receiving positions in his cabinet. Second was a more unexpected result, which would be the a rapid rise in relations between the U.S.A. and CSA. The reason for this stemmed back a decade. During the Civil War, William B. Hazen had been a general, and had been wounded during the Union Assault on Washington, and had been left on the field after the Union rout. After the battle, CSA forces were sent out of their fortifications to bring in the Union wounded, and Hazen had been brought in personally by General John B. Gordon, who had been commanding a brigade in that battle. Gordon saw to the care of Hazen, and soon the two of them became good friends. Now with the friends holding the positions of chief executives of their respective countries, they quickly sparked up their friendship again and brought the two nations closer together, focusing particular on demilitarization, as would be expected from former military men. They would accomplish this objective during meetings in Louisville, Kentucky, where both of them attending, and worked out a treaty which saw a shrinking of the army from both sides.

A modern day image of the Peterson-Dumesnil House, where the two presidents met, as they wanted to be out of public eye during the negotiations

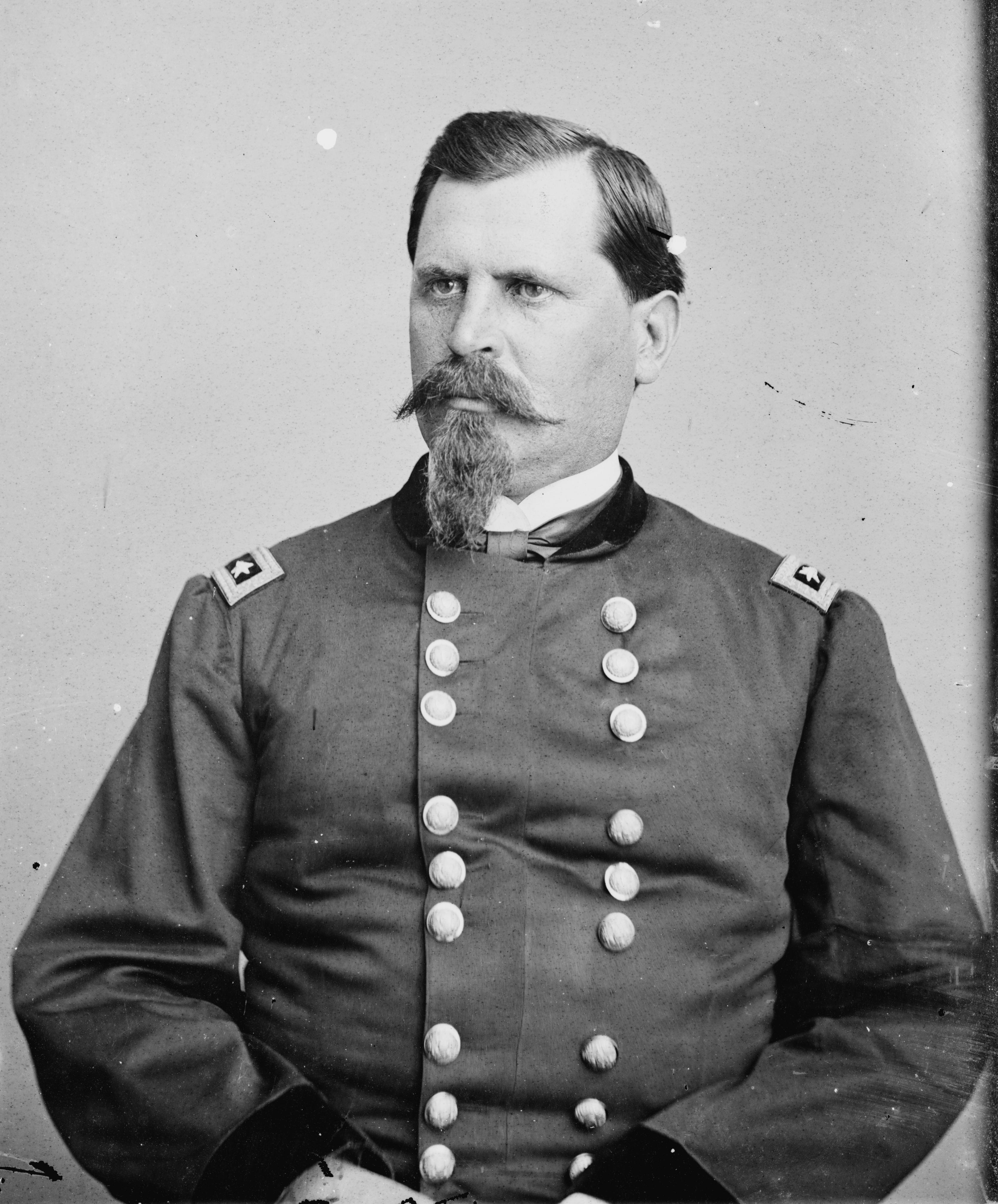

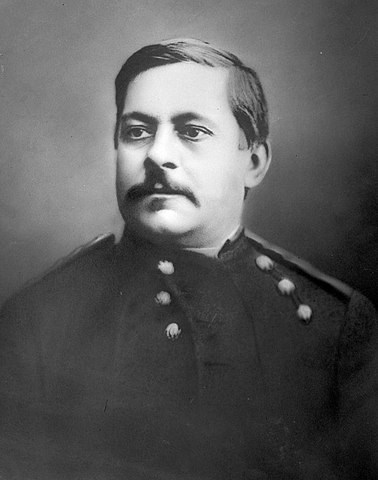

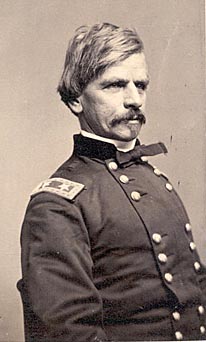

One provision of the treaty stated that the U.S. would halt all incursions into CSA territory, and remove all troops currently within CSA borders. This would mean that Fort Custer, which was located in the CSA Indian Territory, would have to be abandoned by the U.S. When its commander, Colonel George A. Custer of the 7th U.S. Cavalry, heard of this report, he was fuming that a fort with his name attached to it would be handed over to the CSA. On the day when the fort was to be abandoned, Custer brought the 7th Cavalry out of the fort for a final review, leaving only a dozen men under Captain Marcus Reno inside of the fort. During the review, the fort's gunpowder stores exploded, killing all the men inside the fort with only the exception of three men, including Reno. Nonetheless, Custer finished his review, and led his men, now on foot since their horses were killed during the explosion, back into U.S. territory. Once there, Custer court-martialed Reno for negligence leading to the destruction of Fort Custer, and Reno was dishonorably discharged from the army. Many nowadays, however, blame Custer for planning out the explosion, as it was known he disliked Reno, he brought out all of his horses to graze before the explosion, and he was known to hate the idea of a fort with his name attached to it falling into CSA hands.

George A. Custer and Marcus Reno

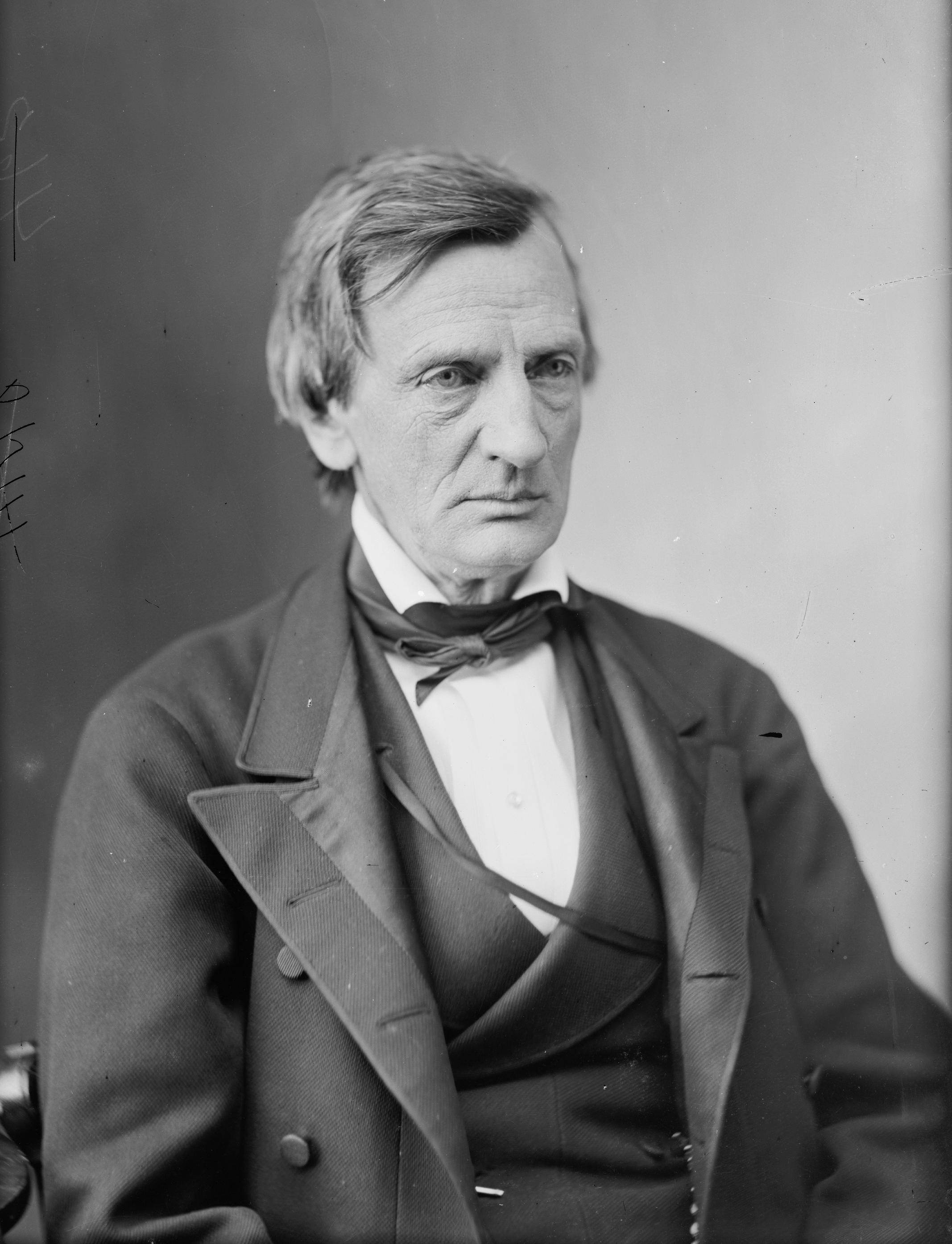

Both men would face backlash from their home countries for the treaty. The CSA Democrats would label Gordon as a secret Unionist, and that he purposely weakening the CSA so the United States could quickly reconquer it. Hazen, meanwhile, would face attacks from his own party, many of whom were still in favor of eventually reconquering the CSA. Nonetheless, the treaty passed in the CSA Congress, and narrowly in the U.S. Congress, making it official. Many Republicans leaders, however, grew resentful against Hazen for this. Hazen, who was quite the disagreeable person himself, would refuse to relent his position, and many assumed he would not receive the Republican nomination for the next election. When asked what he thought of this, Hazen replied, "Why should I care what those unconnected Republican bosses think. I am my own man, and am doing what is best for my country. If they do not renominate me, I shall not care, as I have grown to despise this position anyways." With his position made clear, his rivals in the U.S. Congress, led by Roscoe Conkling, blocked many of his initiatives during the rest of his term, with his only real achievements for the rest of his presidency being minor ones, like reforming westward expansion and making it easier and more accessible to common Americans. In fact, his sole major achievement that was reliant on congress during his term in office following his opening of negotiations with the CSA would be his successful appointment of William M. Evarts to the Supreme Court following the death of Sanford E. Church in 1882. Known and respected within the Republican Party for his brilliant legal mind, the majority of the party could find no objections with his nomination, even if Conkling unsuccessfully attempted to block it out of spite and malice. When his term came to a close at 1880, he made it clear he had no intent of running for a term in office, leaving the position for the next leader of the Republican Party up for grabs. Meanwhile, Gordon and the Liberty Party still remained popular, and it seemed like the next election would likely go in their favor.

Associate Justice William Evarts and New York Senator Roscoe Conkling, who attempted to block the former's approval to the Supreme Court

Hazen and his cabinet:

President: William B. Hazen

Vice-President: William A. Wheeler

Secretary of State: James G. Blaine

Secretary of the Treasury: George F. Edmunds

Secretary of War: Ulysses S. Grant

Attorney General: Jacob D. Cox

Postmaster General: Benjamin Harrison

Secretary of the Navy: John A. Logan

Secretary of the Interior: Henry L. Dawes