After Eulenburg had left office and fled to Switzerland to recover his health, the following year saw a curious wave of suicides. Six high-ranking members of the German army fell victim to the highly profitable criminal activity of blackmailing - and all of them had had some personal relationship with Eulenburg and his friends. Rumours ran wild at the press and court circles alike. When Eulenburg, worried about the way his friends were being attacked, openly defied the terms set down by Harden. He returned to Liebenberg in late 1906, and attended a court seremony to be admitted to the Order of the Black Eagle. A few days later

Die Zukunft started to point out whom Harden was after. Articles using nicknames such as The Harpist and Sweetheart were a thinly-masked smear campaign against von Eulenburg and Count Kuno von Moltke, brother of the Reichskanzler,

Flügenadjutant (aide-de-camp) of Wilhelm II, and military commander of Berlin garrison.

Confrontation with this challenge for the men of the social status of von Eulenburg and von Moltke had two courses: either dueling (criminalized after German unification) or courtroom. Eulenburg chose to pursue the first route. He denounced himself for violating Paragraph 175, using jurisdiction of his Liebenberg estate. After cursory investigation and a short show trial, the presiding district attorney determined that Eulenburg - his personal friend - was clearly not guilty. Moltke, under the advice of a jurist he had hired, followed suit.[

1] His divorsed former wife, Lilly von Elbe, was undermined as an unstable hysteric, discrediting her testimony. Hirschfeld, a known sexologist and advocate of homosexual rights whose testimony Harden had sought to utilize at the courtroom was also silenced via blackmail.[

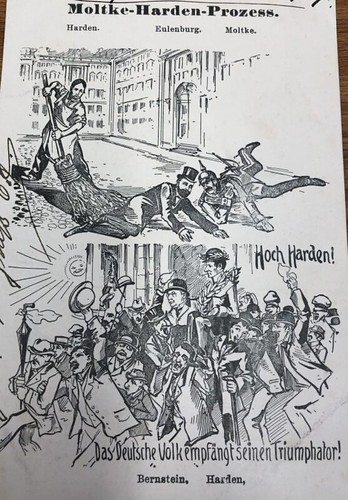

2] The first von Moltke trial was thus seemingly a defeat for Harden, with Kuno von Moltke and Eulenburg completely rehabilitated. But it turned out to be a Pyrrhic victory for the Liebenberg circle.

The trial drew massive publicity because of the high status of the persons involved. And news that Hirschfeld had been threatened from testifying did not stop another leader of the German homosexual movement, Adolf Brand. He had earlier on decided to pursue a strategy that he cynically labelled “

the path over corpses”, publicly outing known public figures to bring the matter of sexual liberation and equality to the focus of public discussion. Brand went public with accusations of von Eulenburg[

3] on a newspaper article soon after the first trial was over, and he was summoned to court to defend himself against a libel suit.

At court Brand defended himself by saying that he did not believe that there was anything immoral or dishonorable about homosexuality, and that he merely wanted to demonstrate how widespread phenomena relations between men really were. Brand delivered evidence from private correspondence of Liebenberg circle - how he had obtained these letters he did not say - only to be sentenced to eighteen months in prison.

Now Harden changed angle. He had his back on the wall on the matter. He knew that Eulenburg was most loathed at sourthern Germany. Journalists close to the Zentrum party saw the Eulenburg camarilla as the “Protestant cartel”, an embodiment of the anti-Catholic attitudes of the ruling Prussian elites, who had rallied around the idea of Protestant Kaiserdom of a Protestant Empire. To them von Eulenburg, “the modern Gustav Adolf”, had blocked the primary-school education reform bill that would have improved the status of Christian churches. He had alienated the Catholic Poles by attacking the liberal policies of Chancellor Caprivi, and constantly spread ill-will towards German Catholics.

Thus Harden and Holstein found it easy to find allies from Bavaria. Anton Städele, editor of a Bavarian newspaper,

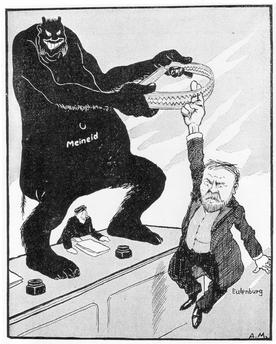

Neue Freie Volkszeitung, soon published a story that claimed that Eulenburg had bribed Harden to suppress the press campaign. Harden immediately sued Städele for libel. This trial was naturally held in Munich, at the kingdom of Bavaria, where the notoriously anti-catholic Eulenburg could not use the power of the Prussian state authorities to aid his cause. A trial involved new witnesses, Jakob Ernst and Georg Riedel, who both gave sworn testimonies where they accused Eulenburg

in absentia of homosexual acts. The sympathy of the Bavarian court were obvious. Städete did not even try to defend himself, and Harden was allowed to bring evidence that had nothing to do with the original case. Allowing the plaintiff to furnish proof that he had been grossly libelled, using witnesses already subpoenaed by another court, County-Court Judge Karl Maier greatly overstepped his legal rights. Yet he publicly stated that “

the truth had to be brought to light.” Max Bernstein, Harden's attorney, was thus able to use the statements of Ernst and Riedel to point out that Eulenburg had committed perjury.

The Munich trial stunned the public both in Germany and abroad. For the German court elites, the mood was mixed. Some felt that Eulenburg had been disgraced beyond repair, while others viewed the attacks as false testimonies bought by unknown enemies of the camarilla. The socialists were now publicly following the court proceedings, and their newspapers were eagerly looking for signs for double standards in the court proceedings of commoners and aristocrats.

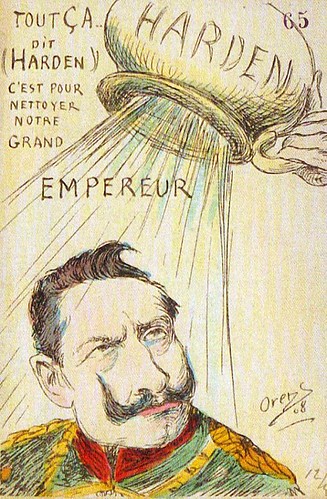

Meanwhile Wilhelm II was furious. The Kaiser had initially taken up some distance to his former Chancellor after Eulenburg had left office. Yet when the scandal went on, he was adamant that Eulenburg should stand his ground and defend his honour at court.

“

The trial must continue, even if E is consumed by the flames. Otherwise the whole business will have been in vain, and the Scweinerei will start all over again!" When Eulenburg sued Harden for libel, the tactic of Harden and his legal team worked. Eulenburg had to meet the witnesses from the Munich trial, and confront the two Bavarians directly. The case displayed the hidden North-South antagonism and religious tensions of German Empire in broad daylight. Eulenburg defended himself as a Prussian Protestant and Patriot, under attack by a foul Jesuit plot. It was a disastrous performance from Eulenburg, whose prejudices against Catholic Bavarians became obvious to all. When his wife tried to defend her husband by referring the people from the southern mountains as "

simple children of nature", the press had a field day. During the trial Eulenburg swore under oath of cleansing that the two witnesses from Munich trial were liars, and that he had never violated Paragraph 175, denouncing "homosexual filth" of any kind.

This was the moment Harden and Holstein had been waiting for. When Harden was sentenced to pay compensations for Eulenberg and the whole juridical process seemed like a politically motivated case of class justice, the public outrage was immense.

Now Holstein contacted Commissioner Tresckow of the Berlin Police, and forwarded him the secret Hohenlohe-Eulenburg protocol. Soon three police investigators from the notorious Vice Squad of Berlin police, director of the the Berlin State Court and a forensic physician arrived unnannounced at the Liebenberg estate to conduct a search. It turned out that in a moment where he had been forced to choose between his brother or von Eulenburg, Reichskanzler von Moltke had realized that sacrifices would have to be made. The Royal Prussian Ministry had at the Behest of Imperial Chancellor von Moltke ordained that von Eulenburg should be put under house arrest.

1. Unlike in OTL.

2. This happened later on in OTL as well, and a more determined law team would most likely have pursued a similar counter-blackmail strategy behind the scenes earlier on.

3. Since von Bülow is dead in TTL, Adolf Brandt chooses von Eulenburg as his target.