Part 1: Known Unknown

----------------------

Part 1: Known Unknown

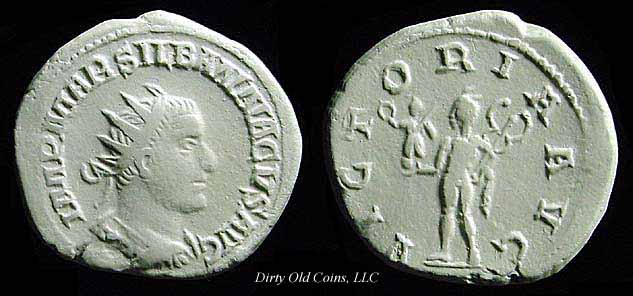

One of the most frustrating but important battles to study by far is the Battle of Resaena, which took place in what was then Roman Syria in 243. Other than the fact that Roman and Persian arms clashed with great ferocity when the event took place, literally no known contemporary historians, eastern and western alike, despite the latter's tendencies to describe their so-called third century as the end of the world, shine any details on what truly happened on that fateful day.

The only clear thing is that the army of Shapur I, king of kings of Iran, prevailed over the one led by the able Roman general and praetorian prefect Timesitheus (1).

Shapur being followed by his sons and nobles.

But the consequences, oh, those are described by both sides with vivid detail. Shortly after his victory, Shapur led his army and attacked the great city of Antioch, an important center of trade and capital of Roman Syria. The city fell after a short siege and the victorious men from Iran were described as "ravaging the city's riches and deporting all of its inhabitants" after which the bulk of them crossed the Euphrates back into home territory. However, Antioch itself remained under an occupation force, which showed that the son of Ardashir, perhaps emboldened by his victory and his glorious ancestors, intended to keep the city in his control, rather than just pillage it.

For the historians of the west, Resaena proved to be the beginning of the end of the Roman Empire as they once knew it. For those who hailed from the east, it was the beginning of the rebirth of one of the greatest civilizations to ever exist in the world, after centuries of foreign (Greek) domination and incompetent Arsacid rulers.

Such is the memory of this cataclysmic event, so famous and mysterious at the same time.

------------------

(1) This is the POD. IOTL, Shapur was defeated, and though the Persians later defeated the Romans and prevented them from marching on Ctesiphon at the Battle of Misiche, the King of Kings by then was content with favourable border concessions and an indemnity from emperor Philip the Arab.

Part 1: Known Unknown

One of the most frustrating but important battles to study by far is the Battle of Resaena, which took place in what was then Roman Syria in 243. Other than the fact that Roman and Persian arms clashed with great ferocity when the event took place, literally no known contemporary historians, eastern and western alike, despite the latter's tendencies to describe their so-called third century as the end of the world, shine any details on what truly happened on that fateful day.

The only clear thing is that the army of Shapur I, king of kings of Iran, prevailed over the one led by the able Roman general and praetorian prefect Timesitheus (1).

Shapur being followed by his sons and nobles.

But the consequences, oh, those are described by both sides with vivid detail. Shortly after his victory, Shapur led his army and attacked the great city of Antioch, an important center of trade and capital of Roman Syria. The city fell after a short siege and the victorious men from Iran were described as "ravaging the city's riches and deporting all of its inhabitants" after which the bulk of them crossed the Euphrates back into home territory. However, Antioch itself remained under an occupation force, which showed that the son of Ardashir, perhaps emboldened by his victory and his glorious ancestors, intended to keep the city in his control, rather than just pillage it.

For the historians of the west, Resaena proved to be the beginning of the end of the Roman Empire as they once knew it. For those who hailed from the east, it was the beginning of the rebirth of one of the greatest civilizations to ever exist in the world, after centuries of foreign (Greek) domination and incompetent Arsacid rulers.

Such is the memory of this cataclysmic event, so famous and mysterious at the same time.

------------------

(1) This is the POD. IOTL, Shapur was defeated, and though the Persians later defeated the Romans and prevented them from marching on Ctesiphon at the Battle of Misiche, the King of Kings by then was content with favourable border concessions and an indemnity from emperor Philip the Arab.