You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Stonewall Jackson's Way: An Alternate Confederacy Timeline

- Thread starter TheRockofChickamauga

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Threadmarks

View all 106 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter Seventy-Nine: The Presidency of Charles E. Hughes Chapter Eighty: La Guerre est Finie, la Fin est Venue Chapter Eighty-One: The Mexican Presidential Election of 1917 Chapter Eighty-Two: The U.S. Presidential Election of 1920 Chapter Eighty-Three: The French Fallout Chapter Eighty-Four: Foch, France, and Fraternity? Chapter Eighty-Five: The World Responds Chapter Eight-Six: The CSA Presidential Election of 1921

Chapter Four: Gettysburg, Day 1

Chapter Four: Gettysburg, Day 1

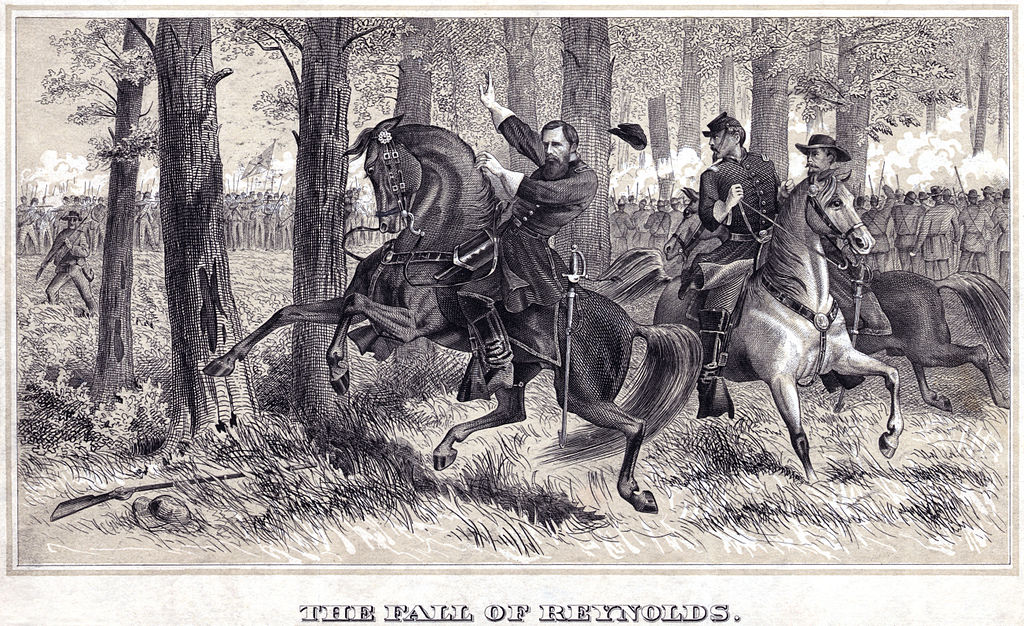

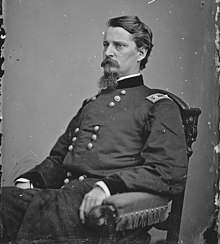

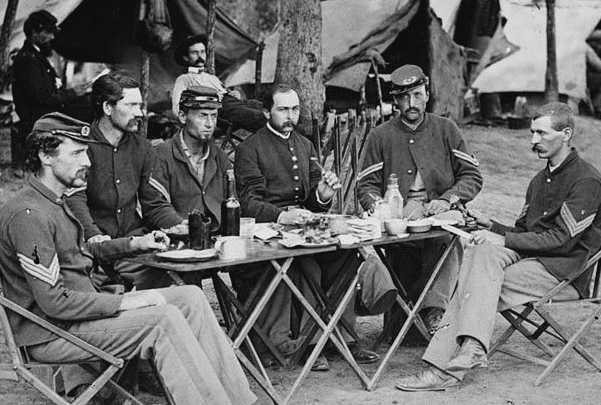

Union Generals John Buford and John Reynolds observe their lines, and plan their assault on Confederate lines.

As what began a skirmish began heating up into a full fledged battle, both sides began requesting reinforcements, with the Confederates managing to bring more sooner, with Trimble bringing up the rest of his division to help in the battle. This help drive back Buford's cavalry, but Buford still had one last trick up his sleeve. While he and his men had been putting up their brave and valiant stand, they had been buying time for John Reynolds and his I Corps to come to their support, which would shift the battle back into their favor. By trading lives for time, Buford was able to hold out long enough for Reynolds to arrive. With his arrival, the battle now shifted into the favor of the Union. Buford and Reynolds planned to exploit this by pushing their troops forward and breaking the Confederate lines. Just prior to the plan being put in motion, however, a sniper would fatally shoot John Buford through the heart, with his limp body falling into the arms of Reynolds. Reynolds would then turn to Myles Keogh of Buford's staff, and reportedly say "I fear the same will befall me today." before removing a necklace with a cross attached and handing to him, asking that it be returned to his fiancee Katherine Hewitt after his death. Despite his fatalistic beliefs, Reynolds would still order the attack, and ride at the front lines with the men of the Iron Brigade as they advanced. Before the attack could truly commence, however, Reynolds would be proven correct, and would be fatally shot from his horse, with some believing he was killed by the same man who killed Buford. Unfortunately for Reynolds' hope of his necklace returning to his fiancee, Keogh would also be killed in these opening actions, still clasping the necklace in his hand.

Union Generals John Buford and John Reynolds observe their lines, and plan their assault on Confederate lines.

A romanticized and inaccurate depiction of Reynolds' death

Confederate troops pushing back the Union soldiers through Gettysburg

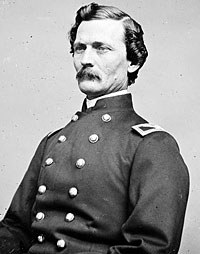

General Winfield S. Hancock and Major Willie Pegram

Last edited:

Chapter Five: Gettysburg, Day 2

Chapter Five: Gettysburg, Day 2

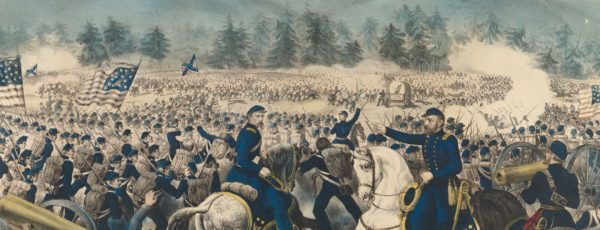

A 1906 painting by Howard Pyle depicting the second day of the battle of Gettysburg, currently hanging in the visitor's center of Gettysburg National Military Park

With two corps of his army in shambles, two corps commanders along with several division commanders killed, and the Army of Northern Virginia possessing the high ground and interposing itself between the Army of the Potomac and Washington D.C., General George Meade announced a council of war on the night of July 1 in his headquarters located near where a portion of Rock Creek splits off to Power's Hill. All of his corps commanders would be in attendance, with John Newton taking over command of the I Corps and John Gibbon leading the II Corps. By this time, all of Meade's army was lined up along Rock Creek facing the Confederate lines, within the exception the V Corps and VI Corps, which would arrive on the morning of July 2. At the meeting, Meade and his generals discussed their plans for the next day. A plan was proposed by Generals Gibbon, Slocum, and Sedgwick in which the I, III, V, and, XI demonstrated along Lee's front, while the II, VI, and XII Corps would attack Lee's position from its left flank of Benner's Hill. The plan held the support of all the corps commanders with the exception of Daniel Sickles, who wanted to be involved in the flanking movement, and Oliver O. Howard, who also wanted to be involved in order to salvage his reputation tarnished on the first day of fighting. The debate would settled, however, when Meade revealed a telegram he had received before the council of war started. In a message which was sent with the name of General-in-Chief Henry Halleck attached, orders were given for the Army of the Potomac to clear the hills between themselves and Washington. This order met the instant disapproval of all the men present, with the exception of Sickles and Howard once again. Despite his reservations about the plan, Meade told his corps commanders it was to be enacted, not revealing the further information in the telegram promising his relief if he did not take immediate action the next day. With it made clear what the general plan was, the details were planned out. The III, II, VI, and V Corps would attack against the Confederate positions on Culp's Hill, Cemetery Hill, Cemetery Ridge, and Little Round Top in that order. Meanwhile, the battered I and VI Corps would protect the Union right, and attack against Benner's Hill. Finally, the XII Corps would guard the left, and attack against Round Top. With the plans in order, the generals readied themselves for the next day of battle.

A 1906 painting by Howard Pyle depicting the second day of the battle of Gettysburg, currently hanging in the visitor's center of Gettysburg National Military Park

Meade's Council of War, July 1, which hangs in Gettysburg National Military Park

A Daniel Troiani painting depicting the charges of the Union line against the Confederates' position

A Currier & Ives lithograph of Meade's Charge, with an inaccurate depiction of Seth Williams on the horse at left, and Meade on the horse at right.

A painting by David Nance, the third of the triumvirate of major modern day Civil War painters, depicting the advance of the Confederates

A painting by Daniel Troiani depicting Stuart's charge

A painting depicting Custer's first last stand by Matthew Kunstler

A photo by Matthew Brady of the Union fallen at the battle of Gettysburg

[1] The men present at this meeting are as follows: J.E.B. Stuart, Wade Hampton III, Fitzhugh Lee, William H.F. "Rooney" Lee, William E. "Grumble" Jones, Beverly Robertson, Albert Jenkins, John Imboden, John Pelham, James B. Gordon, Thomas T. Munford, John R. Chambliss, Thomas L. Rosser, Lunsford L. Lomax, William C. Wickham, Pierce M.B. Young, Matthew C. Butler, Laurence S. Baker, Dennis D. Ferebee, Richard L.T. Beale, Milton J. Ferguson, William H.F. Payne, Vincent "Clawhammer" Witcher, Elijah V. White, Harry Gilmor, Rufus Barringer, John S. Mosby, William H. Chapman, John H. McNeill, William L. Jackson, James Breathed, Roger P. Chew, Channing Price, Heros von Borcke, Henry B. McClellan, John E. Cooke, Robert F. Beckham, William D. Farley, Joel "Banjo" Sweeney, Gustavus W. Dorsey, and William P. Roberts.

[2]Here is a complete list of Union army, corps, division, and brigade commanders killed or mortally wounded at Gettysburg: Army: George Meade Corps: John Reynolds, Winfield Hancock, John Sedgwick, Oliver Howard, Henry Slocum Division: James Wadsworth, John Robinson, Abner Doubleday, John Gibbon, Alexander Hays, David Birney, Andrew Humphreys, Romeyn Ayres, Samuel Crawford, Horatio Wright, John Newton, Francis Barlow, Adolph Steinwehr, Alpheus Williams, John Geary, John Buford Brigade: Edward Cross, Patrick Kelly, Samuel Zook, John Brooke, Alexander Webb, Strong Vincent, Frank Wheaton, Samuel Carroll, George Greene, Joseph Carr, Thomas Smyth, Norman Hall, Hiram Berdan, Emory Upton, Alfred Torbert, Thomas Ruger, George Willard, William Gamble, Joseph Bartlett, Lewis Grant, Davis Russell, Philippe Trobriand, Henry Baxter, Stephen Weed, Adelbert Ames, Elon J. Farnsworth, Freeman McGilvery

[3]Here is a complete list of Union generals captured at Gettysburg: David Gregg, Henry J. Hunt, Wesley Merritt.

Last edited:

With the head of the Army of the Potomac dead or wounded, I wonder who will lead the shattered remains of the army. Sickles, maybe? I didn't see his name in the list of dead or injured (which is rather ironic after he lost his leg in OTL).

Also, you have a way with words, managing to write the battle aspects perfectly in an enjoyable fashion.

Also, you have a way with words, managing to write the battle aspects perfectly in an enjoyable fashion.

SpaceOrbisGaming

Banned

Looks like the war is all but over now. With the battle of Gettysburg a defeat for the Union and the south moving to DC I could see maybe one last battle before it's all said and done. It'll be interesting to see how the wider world reacts to a southern victory. Look forward to the next chapter.

Chapter Six: Gettysburg's Fallout

Chapter Six: Gettysburg's Fallout

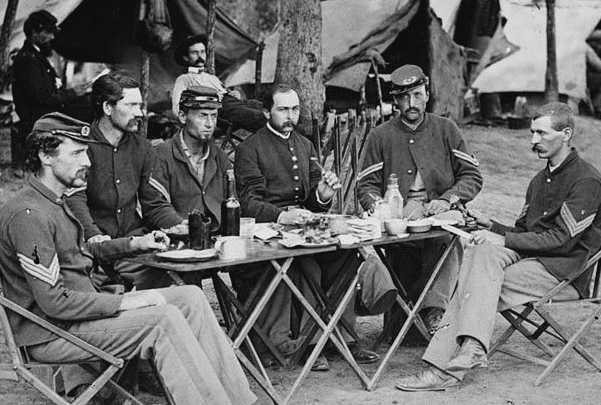

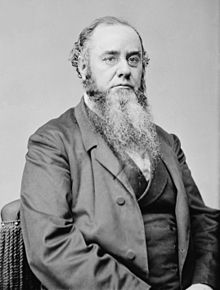

A group of Union in camp around Philadelphia following the defeat at Gettysburg

With Gettysburg being the terrible defeat that it was, calls for someone to place the blame on grew loud. Horace Greeley would write for his New York Tribune, “Manassas, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and even Chancellorsville have been outdone in showing the idiocy of the Army of the Potomac’s high command and their commander-in-chief Abraham Lincoln. It remains to be seen what more disasters await with them at the helm of the ship of state.” With many of the Army of the Potomac's senior officers now dead as a result of Gettysburg, public outrcry was mostly aimed at Lincoln, who remained firmly entrenched in the White House due to the Republican Congress. The blood lust of the public would finally be satisfied when during his testimony before the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, Daniel Sickles revealed the fateful order Meade had received from Halleck ordering the attack. With a name of someone still alive attached to the orders for the attack, the public cried for his dismissal. Facing little other choice, Lincoln would dishonorably strip Halleck of his command, and dismiss him from the army.

A group of Union in camp around Philadelphia following the defeat at Gettysburg

Former Major General Henry W. Halleck, U.S. General-in-Chief July 23, 1862-July 23, 1863

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton

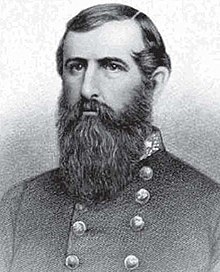

The Winners and Losers of the Sieges of Port Hudson and Vicksburg: Generals Franklin Gardner, John C. Pemberton, Nathaniel Banks, and Ulysses S. Grant

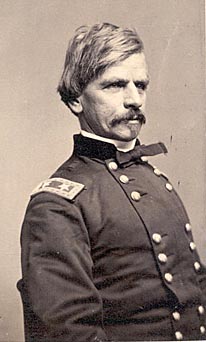

General George Sykes, commander of the Army of the Potomac

Last edited:

SpaceOrbisGaming

Banned

Damn, that was fast. Looks like it's all over but the yelling or in the case of Lincoln the crying at having lost 1/3 of the nation in less then five years. I feel sorry for the Union in this timeline. But as a lover of all things CSA I love seeing them lose. I guess the saying is now the north shell rise again lol.

This thread mostly avoids being a Confederate wank, but I must say- the idea of the Confederates taking 5,500 casualties to the Union 41,000, a difference of nearly 8 to 1, is insane. There's no way that something like that could ever have occurred, on either side of the war. The Battle of Fredericksburg, considered to be the most one-sided major engagement in the entire war, in which Union forces had to cross a river, fight through an entire city, and march across an open field to charge against dug-in, reinforced Confederate lines that were perched on cliffs surrounding them, without any artillery support to speak of, was 5,400 Confederate casualties to 12,700 Union casualties- not even 3 to 1! It was simply a reality of Civil War engagements that no one side could ever really hope to deal enormous casualties without taking a fair number of their own, even with the best possible circumstances, which aren't present in this timeline's Gettysburg. More realistic would be 10,000 to 30,000- still devastating, and a clear indicator of the sheer loss suffered, but not fantastical.

Also, and this is incredibly minute, I just wanted to point it out- you said, "The order had originally been drafted been Secretary of War Edwin Stanton", repeating the word "been" twice. I assume you meant "The order had originally been drafted BY Secretary of War Edwin Stanton". Like I said, a very minor thing, just wanted to point it out in case you hadn't seen the typo.

Also, and this is incredibly minute, I just wanted to point it out- you said, "The order had originally been drafted been Secretary of War Edwin Stanton", repeating the word "been" twice. I assume you meant "The order had originally been drafted BY Secretary of War Edwin Stanton". Like I said, a very minor thing, just wanted to point it out in case you hadn't seen the typo.

Both the low Confederate causality number and the "by" have been fixed. The heavy Union losses stem from two completely unguarded routs, which provided the South with ample opportunity for capturing prisoners with low risk to themselves which battles such Fredericksburg or Chickamauga in our OTL did not have, due to fall of darkness and Thomas' defensive stand respectively. Nonetheless, thank you for pointing out the errors.This thread mostly avoids being a Confederate wank, but I must say- the idea of the Confederates taking 5,500 casualties to the Union 41,000, a difference of nearly 8 to 1, is insane. There's no way that something like that could ever have occurred, on either side of the war. The Battle of Fredericksburg, considered to be the most one-sided major engagement in the entire war, in which Union forces had to cross a river, fight through an entire city, and march across an open field to charge against dug-in, reinforced Confederate lines that were perched on cliffs surrounding them, without any artillery support to speak of, was 5,400 Confederate casualties to 12,700 Union casualties- not even 3 to 1! It was simply a reality of Civil War engagements that no one side could ever really hope to deal enormous casualties without taking a fair number of their own, even with the best possible circumstances, which aren't present in this timeline's Gettysburg. More realistic would be 10,000 to 30,000- still devastating, and a clear indicator of the sheer loss suffered, but not fantastical.

Also, and this is incredibly minute, I just wanted to point it out- you said, "The order had originally been drafted been Secretary of War Edwin Stanton", repeating the word "been" twice. I assume you meant "The order had originally been drafted BY Secretary of War Edwin Stanton". Like I said, a very minor thing, just wanted to point it out in case you hadn't seen the typo.

SpaceOrbisGaming

Banned

How long until the Royal Navy bombards New York?

At the rate this is going would this even be necessary? The Confederacy is already making its way towards DC and unless the Union can pull a 180 in a few days the war is basically over. The army has lost some of it's best and the disastrous PR after the defeat at Gettysburg is likely going to force Abraham Lincoln's hand. What's left of the army is going to have to win the upcoming battle or her majesty's navy is just going to add salt to an open wound. At this point, even with a win, the south should have European support so the Union is boned six ways to Sunday.

At the rate this is going would this even be necessary? The Confederacy is already making its way towards DC and unless the Union can pull a 180 in a few days the war is basically over. The army has lost some of it's best and the disastrous PR after the defeat at Gettysburg is likely going to force Abraham Lincoln's hand. What's left of the army is going to have to win the upcoming battle or her majesty's navy is just going to add salt to an open wound. At this point, even with a win, the south should have European support so the Union is boned six ways to Sunday.

I give the Confederacy ITTL 50 years of life.

SpaceOrbisGaming

Banned

I give the Confederacy ITTL 50 years of life.

Really just 50 years? Their last battle was an impossible good win for them. The Union just had some of it's best people killed or replaced. The only thing I could see messing that up is the institution of slavery which in my opinion is probably going to die out before too long. It'll live maybe until the 1870s but if it lasts much more then that I would honestly amazed. With the Confederacy surviving the Civil War maybe the Spanish-American War becomes the Confederate-Spanish War and they gain Cuba. I know this isn't a Confederate wank but even so, they have had some big wins as of late.

What I see happening is a cold war attitude towards the Union with maybe the Great Union Wall running along the border between the two countries. It'll be interesting to see how the two nations deal with World War one and World War two, that is if the south doesn't collapse in on itself. Maybe post-war we could see how race relations develop over the course of the 19th century. Surely we could see some blacks fight in segregated regiments.

Also, can we see what the CSA looks like on a map ITTL?At the rate this is going would this even be necessary? The Confederacy is already making its way towards DC and unless the Union can pull a 180 in a few days the war is basically over. The army has lost some of it's best and the disastrous PR after the defeat at Gettysburg is likely going to force Abraham Lincoln's hand. What's left of the army is going to have to win the upcoming battle or her majesty's navy is just going to add salt to an open wound. At this point, even with a win, the south should have European support so the Union is boned six ways to Sunday.

SpaceOrbisGaming

Banned

Also, can we see what the CSA looks like on a map ITTL?

Yes, that be great. But wouldn't it just be the CSA but without the state of Kentucky (Unless that was another CSA timeline) but even so a map would be nice to have. Also how soon until we hit the end of the Civil War? It looks like we may be near the end.

What about Missouri? Both states had Confederate governments "in-exile" in our timeline and were equally divided over loyalties with slavery being strongholds in each. For me, Kentucky and Missouri are a pair that stays together.Yes, that be great. But wouldn't it just be the CSA but without the state of Kentucky (Unless that was another CSA timeline) but even so a map would be nice to have. Also how soon until we hit the end of the Civil War? It looks like we may be near the end.

Yes, that be great. But wouldn't it just be the CSA but without the state of Kentucky (Unless that was another CSA timeline) but even so a map would be nice to have. Also how soon until we hit the end of the Civil War? It looks like we may be near the end.

that was another timeline which is a lot less realistic than this

SpaceOrbisGaming

Banned

that was another timeline which is a lot less realistic than this

I kind of guess that but didn't feel like going back and looking. I have been jumping from one thing after another as of late so I must of get the timelines messed up. But I had a feeling it wasn't this story but wasn't sure.

Chapter Seven: The Confederate Assault on Washington

Chapter Seven: The Confederate Assault on Washington

A depiction of Garnett's Brigade, Pender's Division during the assault on Washington. The battle would be a particular importance to Garnett, as Jackson officially rescinded his charges of cowardice against Garnett after the battle due to the bravery he showed in the battle

With the Union Army of the Potomac tied down in Philadelphia waiting for reinforcements, Lee knew the time to attack Washington had come. The long-awaited moment had finally arrived, and Lee positioned his forces in a sieging position around the capital of the United States. Despite the overwhelming confidence Lee had in his army, he would still send a letter to Davis in Richmond, requesting that more troops be raised in the case that the Army of Northern Virginia should fail and be destroyed when the Army of the Potomac moved south. Facing Lee inside Washington were around 20,000 men composing the XXII Corps and various other units in Washington's garrison, mostly inexperienced in actual combat, under General Samuel Heintzelman, former commander the Army of the Potomac's III Corps. Lincoln and the United States government had evacuated Washington the day before Lee had put the city under siege. Knowing the delay would only give advantage to the Union, Lee decided the attack Washington on the third day of the siege, having only waited for Stuart and his command to reconnoiter the ground.

A depiction of Garnett's Brigade, Pender's Division during the assault on Washington. The battle would be a particular importance to Garnett, as Jackson officially rescinded his charges of cowardice against Garnett after the battle due to the bravery he showed in the battle

A painting by David Nance showing Lee surveying his lines one last time before the assault on Washington, with Longstreet riding up to ask for Lee's permission to begin the assault.

A painting depicting the advance of Barksdale's brigade on Washington

General Samuel Heintzelman, the soldier who both lost and saved Washington D.C.

A small monument to Richard R. Kirkland in Fredericksburg, Virginia

Generals James B. Fry and Montgomery C. Meigs

Last edited:

Threadmarks

View all 106 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter Seventy-Nine: The Presidency of Charles E. Hughes Chapter Eighty: La Guerre est Finie, la Fin est Venue Chapter Eighty-One: The Mexican Presidential Election of 1917 Chapter Eighty-Two: The U.S. Presidential Election of 1920 Chapter Eighty-Three: The French Fallout Chapter Eighty-Four: Foch, France, and Fraternity? Chapter Eighty-Five: The World Responds Chapter Eight-Six: The CSA Presidential Election of 1921- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Share: