You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Star-Spangled Expanded Universe of "What Madness Is This?"

- Thread starter Napoleon53

- Start date

Hi. It's been a while since I've posted in this thread, but now I'm back with something I've been working on for a while. So without further ado, let's revisit the Middle East!

A History of the Islamic Republic of Turkey

The flag of the Islamic Republic of Turkey, also the flag of the Ottoman Empire from 1844 to 1856

Map of the Islamic Republic of Turkey in 1900

The flag of the Islamic Republic of Turkey, also the flag of the Ottoman Empire from 1844 to 1856

Map of the Islamic Republic of Turkey in 1900

The history of the Islamic Republic of Turkey began immediately with the end of the Ottoman Empire. To be more specific, the Islamic Republic of Turkey was born out of the fall of the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of the Imperial-Ottoman War, known by some historians as the “10th Crusade.” As most all European schoolchildren were taught by the time they were teenagers, during the mid-1850s, the Ottoman Empire collapsed under the might of a massive invasion from the Franco-Spanish Empire and its allies, as well as from the League of Tsars, led by the Russian Empire and including Romania and Bulgaria. The rest, as they say, is history.

With the Franco-Spanish establishment of the Grand Realm of the Levant, the League of Tsars, in an effort to counteract and contain the power of the Franco-Spanish Empire, signed the Treaty of Constantinople on January 1, New Year’s Day, 1857. This treaty established Constantinople as an independent but Orthodox state under control of three viceroys, one Russian, one Romanian and One Bulgarian, each representing the interests of each nation in the League. The sense of rage and anger felt by the Turkish people towards the empires of Catholic and Orthodox Europe for their conquest, defeat and division of the once-great Ottoman Empire would fuel a never-ending fire of hatred against the Catholic and Orthodox nations of Europe that would come to have further effects later on in the future.

After the immediate collapse of the Sublime Port, the remnants of Turkey had no official government, with numerous warlord cliques led by former Ottoman Army generals claiming to be the legitimate government of Turkey and the legal successor to the Ottoman Empire scattered throughout Asia Minor. However, the largest and most powerful of these warlord states was the Ankara government of General and last grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire Mustafa Reşid Pasha, headquartered in the eponymous Turkish city and established immediately after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, styling itself as the Republic of Turkey. With Mustafa Reşid Pasha having the most powerful armies in Asia Minor, all of the other desperate warlords were persuaded to swear allegiance to his government by the end of June, 1857. On July 14, 1857, the Republic of Turkey was officially declared in Ankara under an interim government led by interim President Mustafa Reşid Pasha.

With the Franco-Spanish establishment of the Grand Realm of the Levant, the League of Tsars, in an effort to counteract and contain the power of the Franco-Spanish Empire, signed the Treaty of Constantinople on January 1, New Year’s Day, 1857. This treaty established Constantinople as an independent but Orthodox state under control of three viceroys, one Russian, one Romanian and One Bulgarian, each representing the interests of each nation in the League. The sense of rage and anger felt by the Turkish people towards the empires of Catholic and Orthodox Europe for their conquest, defeat and division of the once-great Ottoman Empire would fuel a never-ending fire of hatred against the Catholic and Orthodox nations of Europe that would come to have further effects later on in the future.

After the immediate collapse of the Sublime Port, the remnants of Turkey had no official government, with numerous warlord cliques led by former Ottoman Army generals claiming to be the legitimate government of Turkey and the legal successor to the Ottoman Empire scattered throughout Asia Minor. However, the largest and most powerful of these warlord states was the Ankara government of General and last grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire Mustafa Reşid Pasha, headquartered in the eponymous Turkish city and established immediately after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, styling itself as the Republic of Turkey. With Mustafa Reşid Pasha having the most powerful armies in Asia Minor, all of the other desperate warlords were persuaded to swear allegiance to his government by the end of June, 1857. On July 14, 1857, the Republic of Turkey was officially declared in Ankara under an interim government led by interim President Mustafa Reşid Pasha.

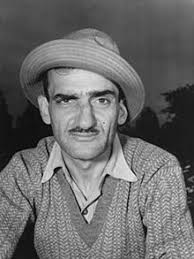

Mustafa Reşid Pasha, first President of the Islamic Republic of Turkey

The most immediate problem for the new Turkish Republic was none other than the Kurdistan Rebellion. The Kurdistan Rebellion had begun in 1855 as a direct result of the outbreak of the Imperial-Ottoman War. However, the rebellion had always been very desperate and disorganized, and the Kurdish militias were also in a state of complete disarray. As a result, in an effort to save face, bring legitimacy to his new government and to regain some old Ottoman land, the Turkish Republic, without an official declaration of war, invaded the nascent Free State of Kurdistan. During the Turkish-Kurdish War, the Kurdistan Rebellion was brutally suppressed by the invading Turkish armies, with a number of massacres and other war crimes occurring throughout the campaign, although President Mustafa Reşid Pasha personally commended these actions and reprimanded any perpetrators of such acts. Throughout much of the history of the new Turkish nation, Kurdish nationalism within Turkish Kurdistan would continue to remain a continuous problem.

Flag used by the Kurdish Rebels during the Kurdish Rebellion

The situation with Kurdistan was similar to the situation between Turkey and the new Republic of Armenia. As the Ottoman Empire was collapsing, the Armenian people rose up in revolt against their Ottoman Turkish masters throughout the Caucasus and Asia Minor, and supported by the Russian Empire with weapons and money. At first, the Armenian rebels were represented by numerous different groups, but soon they all came under the leadership of the young rebel leader, partisan, writer, poet and intellectual Mikayel Nalbandian (November 14, 1829-September 16, 1902), an ethnic Armenian from the Armenian town of Nakhichevan-on-Don near Rostov-on-Don in the Russian Empire who moved into Ottoman Armenia soon after the outbreak of the Ottoman-Imperial War in an effort to fighting alongside Armenian partisans and to foment a larger Armenian rebellion against Ottoman rule. As a result, unlike the Kurdish Rebellion, the Armenian Rebellion was much more strong and unified against the Ottoman Turks. Thus, with the signing of the Treaty of Constantinople, the Republic of Armenia was diplomatically recognized by the great powers of Europe. In the aftermath of the Armenian War of Independence, numerous Armenians living in the Islamic Republic of Turkey moved into the Republic of Armenia. However, a number of Armenians continued to live within the borders of Turkey, and tensions continued to remain between Turkey and Armenia over the subsequent decades, not just for this reason, but also because many in the Turkish government saw Armenian lands in Asia Minor as rightfully Turkish lands.

Flag of the Republic of Armenia

Mikayel Nalbandian, first President of the Republic of Armenia

By the beginning of 1858, the nation of Turkey had finally come under a stable and functional government, with the city of Ankara as the official capital of the new Republic of Turkey. With the continuing pacification of the Kurdish lands and with some stability finally returning to the Turkish lands of Asia Minor, President Mustafa Reşid Pasha knew that a constitution needed to be drafted for the new nation, and he spent months upon months working with politicians, generals, clerics and other important figures in Turkish society to write and formulate said constitution. The result was the Turkish Constitution of 1859, which officially established and renamed the nation as the Islamic Republic of Turkey, which was done in an effort to placate both traditionalists and political Islamists in the new Turkish government, all of whom who resented the fall of the Ottoman Empire, and with it the fall of the Islamic Caliphate, and did not want to see the centuries-old Islamic traditions within Turkey be destroyed. Under the Turkish Constitution of 1859, the Islamic Republic of Turkey was officially established as a nominally-democratic republic under Islamic and Sharia Law, largely as a holdover from the era of the Ottoman Empire. The Islamic Republic of Turkey, while not an Islamic fundamentalist state, was still a religious state. As a result, the Sunni variant of the Islamic religion was the only religion favored by the state, with other sects of Islam remaining marginalized. Furthermore, other religions like Christianity and Judaism, while still having certain protections as Abrahamic Religions, gradually became more and more targeted by the government of Turkey as the decades went on, even more so than during the latter part of the Ottoman Empire. As the Danish writer and historian Jorgen Blume stated in his book A History of the Turkic People; “The new Turkish republic was no revolutionary state like the French Republic formed after the regicide of the Bourbons. On the contrary, it was simply the Ottoman Empire without a Sultan and without an Empire. The Islamic Republic of Turkey was a semi-democratic yet still an oligarchic and religious nation.”

The first years of the Islamic Republic of Turkey were a time of consolidation and reorganization. President Reşid Pasha also managed to pass certain moderate reforms, such suffrage for all men over the age of twenty-one years of age, limited land reform and the establishment of state-run Islamic schools and educational institutions. On October 19, 1865, after less than a decade in power, President Mustafa Reşid Pasha died of natural causes in his bedroom in the Presidential Palace in Ankara at the age of 65. A week later, he was given a massive funeral in Ankara, with the people of Turkey praising and eulogizing him as the father of the nation and the savoir of the Turkish people. Immediately after his death, Mustafa Reşid Pasha was succeeded as President of Turkey by his right-hand man and former protégé Mehmed Emin Âli Pasha, with him having also been a former general in both the Ottoman and Turkish armies.

The first years of the Islamic Republic of Turkey were a time of consolidation and reorganization. President Reşid Pasha also managed to pass certain moderate reforms, such suffrage for all men over the age of twenty-one years of age, limited land reform and the establishment of state-run Islamic schools and educational institutions. On October 19, 1865, after less than a decade in power, President Mustafa Reşid Pasha died of natural causes in his bedroom in the Presidential Palace in Ankara at the age of 65. A week later, he was given a massive funeral in Ankara, with the people of Turkey praising and eulogizing him as the father of the nation and the savoir of the Turkish people. Immediately after his death, Mustafa Reşid Pasha was succeeded as President of Turkey by his right-hand man and former protégé Mehmed Emin Âli Pasha, with him having also been a former general in both the Ottoman and Turkish armies.

Mehmed Emin Âli Pasha

Mehmed Cemil Bey

It was during the 1870s and 1880s that Islamic fundamentalism began to increase in popularity within the Islamic Republic of Turkey. While Islamic Fundamentalism was always a force to be reckoned with within the new Turkish nation, it was at first a more minor current within Turkish politics. However, beginning in the 1870s and continuing into the 1880s, Islamic Fundamentalism began to increase in popularity due to numerous factors, such as increasing unemployment, increasing diplomatic and trade relations with Turkey and the Franco-Spanish Empire, the Russian Empire and other European nations, growing tensions between Turks and non-Islamic and oftentimes non-Turkic ethnicities, among other reasons. Throughout the nation, numerous Islamic clerics begin to call for a return to a more authentic form of the Islamic faith for said faith to have an all-encompassing power over the Turkish government. Nevertheless, during the 1870s and 1880s, the Islamic Fundamentalist movement in Turkey was wide and desperate, having been represented by numerous loose political movements, political clubs and individual Islamic clerics. Still, all of this would begin to change in the 1890s.

In December, 1890 and in January, 1891, many of the aforementioned Islamic Fundamentalist and Radical Islamist political movements, political clubs and clerics meet for a hap-hazard conference in the city of Sivas. At the end of the aforementioned Sivas onference on January 30, 1891, it was agreed upon that the many groups present would merge into a new political party known as the Sons of Turkey (Türkiye'nin oğulları), a far-rightist, reactionary, Islamic Fundamentalist and Turkish nationalist political party. Thus, the first true political party representing Islamic Fundamentalism and Radical Islamism within Turkey was established. The Sons of Turkey called for the establishment of an Islamic Fundamentalist government to take over Turkey and to have total control over the entirety of the Turkish government and all Turkish public institutions. The party also called for segregation between Turks and non-Turks within Turkey, a limited amount of Turkification of non-Turks and population exchanges with Greece, Armenia and other nations. The party also called for new government social programs under the guise of “Islamic Charity” for the benefit of all Sunni Muslims within Turkey. Lastly, the new government was against any forms of social progressivism and sought to go back to a more “traditional” variant of Islamic society. The first leader of the party was Mehmed Ferid Pasha, an influential intellectual and formerly independent Islamist politician in the Turkish Parliament. Thus, a new and powerful force within Turkish politics had been born in earnest.

Mehmed Ferid Pasha

President Mehmed Ferid Pasha was inaugurated as President of Turkey on September 20, 1892. Almost as soon as he came to power, Ferid Pasha began to put his plans for Turkey into motion. Non-Sunni Muslims were officially made second class citizens by a number of government decrees issued throughout 1893 and 1894, decrees which barred non-Muslims from certain professions and educational institutions and prohibited inter-faith marriages. In an effort to subdue Kurdish nationalism, Ferid Pasha passed the Settlements Act of 1894, which legally opened up Kurdish lands within Turkey for ethnic Turkish settlement. As a part of this law, several new villages were established and then run by the Turkish government solely for the habitation of Turkish civilians. Over the next decade, this law increased the Turkish population of the Kurdish lands of Turkey and thus greatly increased tensions between the Turkish and Kurdish populations of the Islamic Republic of Turkey. As a result, numerous riots between Turks and Kurds in Turkish Kurdistan took place throughout the late-1890s, with the Turkish Army being sent in to quell the riots and hitting hard against the Kurdish rioters in favor of the Turkish settlers. These events would greatest emboldened the burgeoning Kurdish nationalist movement.

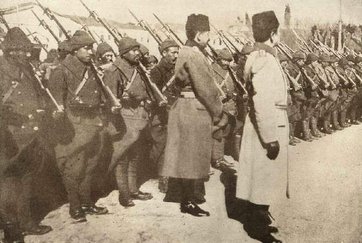

Turkish Islamic Army battalions on the march through Kurdistan, circa 1895

Turkish Islamic Army soldiers camped outside of a Kurdish village, 1899

Soon after the Turkish parliamentary elections in 1895, which gave the Sons of Turkey a majority within the Turkish parliament, President Ferid Pasha ratified a new constitution for the Islamic Republic of Turkey, known as the 1895 Constitution. This new constitution officially reestablished the Islamic Republic of Turkey as an Islamic Fundamentalist and Theoretic republic, under a strict form of Sharia Law. This new constitution also re-established the Islamic Caliphate with the President of the Islamic Republic of Turkey as the Caliph of Islam. Last but not least, the nominally democratic elections within Turkey would be preserved, but only Sunni Muslims would be allowed to vote in said elections. It should be noted that in the subsequent elections within the Islamic Republic of Turkey, the elections were only ceremonial and were all won by Ferid Pasha. With Ferid Pasha being elected over and over again in sham elections, oftentimes with no challengers, Ferid Pasha became a dictator in all but name, and thus democracy in Turkey existed only on paper. With the passing of the Government Safety Acts in 1896, all opposition parties in Turkey were banned, and over the coming years, all opposition figures are purged from Turkish society, with opposition figures being jailed, exiled or even assassinated.

In the late 1890s and early 1900s, the Sons of Turkey government of Ferid Pasha made an effort to deal with the issue of the Turkish minorities, this time once and for all. Towns with a large or medium sized numbers of non-Turks were segregated between Turks and non-Turks, and large numbers of Turkish Army units were sent to these towns to prevent minorities from acting out against the Turkish and Muslim majority. The Turkization Acts were passed in 1897, which would officially begin the process of culturally assimilating a number of majority Armenian, Greek, Kurdish and Arab villages in Turkey. As a result of these programs, all languages other than Turkish were outlawed in public spaces and in education and all villagers had to adopt Turkish given names. However, this new law bought up the issue that in Turkey there were no official surnames and family names. As a result, the Turkish Surname Law was passed in 1898, legally required all ethnic Turkish citizens to adopt a Turkish surname by December 31, 1900, the last day of the 20th Century. President Mehmed Ferid Pasha adopted the surname of Millî-Şef, with said surname meaning “National Chief”, thus his full name became Mehmed Ferid Millî-Şef. Finally, in 1900, the Segregation Acts were passed, thus officially enforcing segregation between Turks and non-Turks within all Turkish cities and towns, with the only non-ethnic Turks not segregated being those that were already culturally Turkized or those that agreed to become a part of the Turkization Program. It should also be noted that during the 1900s, a number of pogroms took place against the Greek, Armenian, Kurdish and Jewish populations of the Islamic Republic of Turkey. While the Turkish government officially condemned these actions, they never anything to stop or discourage said actions.

Turkish Infantrymen garrisoned outside of a Greek village in the Pontus region, 1905

As a direct result of all of these many different laws and policies, numerous immigrants left Turkey to escape the repressive government of the Islamic Republic. Many of these immigrants initially moved to neighboring nations and regions such as the Persian Empire, the Levant, Iraq and the former Ottoman regions of Europan Egypt and Europan Libya. By 1910, the Islamic Republic of Turkey saw a lot of immigration to other nations and regions such as Europa, Nordreich, the Swiss Confederation, the Netherlands, Sweden and colonies such as the United Empire of Brazil and Rio de la Plata, French Australia and Dutch South Africa. It should be noted that most of the Jews of Turkey emigrated to the Grand Realm of the Levant, particularly the region of Palestine, the historical homeland of the Jewish people.

During the Great World War, the Islamic Republic of Turkey under the aging President Millî-Şef remained in a state of neutrality. The Islamic Republic of Turkey remained neutral for a number of reasons. For one thing, the Islamic Republic of Turkey distrusted the alliance between Egypt, Iraq and Persia, with President Millî-Şef claiming that the aforementioned alliance had desired to dominate Turkey and to liberate Kurdistan. In addition, the Turkish military was still in a state of neglect and disorganization, with the Turkish Army still using largely outdated weaponry and technology. Thus, the Islamic Republic of Turkey did not have the strength to take back Constantinople from the League of Tsars.

Generals and officers of the Turkish Islamic Army, 1912

Turkish Infantry Regiments on Review, circa 1910

General İsmail Cevat Çobanlı succeeded Millî-Şef as the President of the Islamic Republic of Turkey. Çobanlı was the first military president of the Islamist Republic of Turkey during the Islamist Era. He would serve as President of Turkey until his death in 1940.

İsmail Cevat Çobanlı

After the end of the Great World War in 1914, the Islamic Republic of Turkey still had one long-running and serious problem to contend with, and this problem was the issue of Kurdistan. The Turkish government refused to give up its lands of Turkish Kurdistan, as the Turkish Islamist government viewed the Turkish domination over the Kurdish lands as a springboard to regain other formerly Ottoman lands, such as Armenia, the Levant and Iraq. As a result of the Turkish unwillingness to give any self-rule to the lands of Turkish Kurdistan, things were about to change in the Middle East forever.

Last edited:

Slow Food Done Quick: The Rise of Smithfield's Stop n' Serve

A gaggle of Yankee tourists seen outside a Smithfield's in Charleston, 1938

However, it was not to last. While the annexation of East Carolina and Yonderland provided the material for quick growth, once those territories were settled to maximum capacity problems began to emerge. The Cokie economy was still largely dependent on the sale of raw materials to America and Britain, and the final stabilization of Mittleafrika drastically decreased the prices of many of these goods. Furthermore, with no more land to settle or natives to exploit, this model of economic expansion reached a temporary limit. A bad situation became worse when it was revealed that several corrupt officials had siphoned off sums of money intended to pay down the debt. While it hadn't effected the size of the debt too much, it sparked a panic among investors who held Carolinian bonds, and saw a credit downgrade for the nation as well as falling bond prices and higher interest rates on existing bonds, making the national debt harder to service. This translated into a wider run on the market and banks in 1927, which decimated Carolinian and Yankee investors. To cap it all off, abnormally hot and dry weather in the mainland caused severe droughts in 1928 and 1929, crippling the all-important tobacco, grain, and cotton industries. In short, by 1930 the Carolinian economy was in a free-fall that even affected their American neighbors, although the Yankee economy was still able to chug along quite well.

Even in the best of economic times, the Confederation was quite subservient to American whims. In 1930, the House of Citizens authorized the construction of the Destiny Road unanimously. It was actually very smart for the Cokies to accept. The Yankees agreed to hire local laborers to keep costs down, giving employment to Carolina's recently unemployed as well as to many badly impoverished mountain hillbilly folk. Furthermore, they would be building valuable infrastructure the nation had needed to build anyway, but had failed to do so. Finally, the creation of "The Donut" would give Carolina the opportunity to capitalize on valuable tourist dollars, further boosting the economy. In short, the construction of the Destiny Road saved the Carolinian economy from a potentially catastrophic meltdown. When construction began, newspapermen and business tycoons from Nashville to Charleston toasted the Yankees and the Gamble Administration for this "economically sound and most profitable partnership."

Investors and account holders make a run on the First National Bank of West Carolina in Nashville (1927)

This already strong sentiment was fanned by the media into an inferno. By 1933, protests were being organized at every single Vanvleet opening, and protests would spontaneously erupt outside established locations. During rowdier incidents, rocks were thrown through windows and customers had obscenities yelled at them. Cokies who worked at these establishments could expect to have their cars keyed or have rotten fruit thrown at them. When Vanvleet sent down some representatives from up North on a goodwill tour in April of 1934, they were attacked by some rowdy conservatives who threw buckets of boiling hot sweet tea at them. Vanvleet's infamously did not serve that most Carolinian of beverages at any of their locations, thus adding a symbolic angle to the attack. The attackers were arrested and hanged, but the protesters responded by getting more organized. Wealthy aristocratic wife Daisy Harrison founded the Association to Preserve Carolinian Culture (APCC) on June 15th, 1934 and with several other wealthy aristocratic families began funding not only more organized protests, but also lobbying in the House of Citizens. There was definitely an impact on Vanvleet's business, although they never admitted it. By 1935, the number of Vanvleet's had shrunk from an all-time high of over 150 locations across the country (mainly achieved by buying out small restaurants) to less than 120.

1935 is also when a young Cokie man by the name of Thomas Montgomery Smithfield saw an opportunity. Having recently won a great deal of money on a successful horse racing bet, the Nashville native decided to use some of what he learned as a line cook in the Army and founded his first restaurant, called Smithfield's BBQ and Chicken. Shortly after he opened his doors, Nashville was convulsing under another series of anti-Vanvleet protests. Seeing a marketing opportunity, he put up a giant billboard saying simply "Smithfield's: We make our tea sweet!" Leaving aside the fact that every diner in Nashville did the same thing, his dig at Vanvleet's saw business skyrocket. After several months of brisk business, Mr. Smithfield had another brainstorm; he would establish his business as a competitor to Vanvleet's. The final piece of the picture came when he added the master stroke of adding gas pumps out in front of his diner. After acquiring several loans and renaming his store Smithfield's Stop n' Serve, he built a second location right off of the Destiny Road, just before they came into Nashville proper. Advertising cheap gas and real down home Cokie cooking, the location attracted Cokie and Yankee alike. Serving pulled pork, fried chicken, hushpuppies, collard greens, Cokie-Cola, and of course, sweet tea, the simple fare of his restaurant was adored by the public. The fact that he promised his meals would be out in the same time as Vanvleet's certainly helped. By 1936 Smithfield had made so much money that he opened 5 new locations, two in Memphis, one in Nashville, one in Charlotte, and one in Columbia. He specifically targeted his locations to compete with Vanvleet's in major hubs along the Destiny Road.

Needless to say, Vanvleet's wasn't happy about this. They couldn't do much to the protesters, that's how lynch mobs started in Ol' Caroline. However, the company did take it upon itself to harass Smithfield's as the company grew rapidly. This irritated Smithfield to no end, and to beat back the waves of Yankee thugs, he instituted a system of so-called "Stop n' Serve Safety Officers." These were uniformed officers that were openly armed and officially there "to ensure our customers feel safe from ruffians and hooligans while at our stores." Initially only a dozen men with guns and shabby uniforms, by 1940 they would number in the hundreds and be as intimidatingly outfitted as any Yankee mercenary outfit. A final alteration to the company's overall business model was made in 1938 by Mrs. Janice Earnhardt Smithfield, who suggested to her husband that each location be decorated in "Cokie kitsch" to further attract tourists and bolster the restaurants' down home Cokie credentials. Each location was outfitted with a variety of Carolinian memorabilia, including portraits of Jackson, Cokie-Cola signs, flags, and copies of "old-timey" documents. Minor as this might seem, it really did help put Smithfield's over the edge. A visit to at least one location was now considered mandatory for any Yankee tourists visiting Carolina. For most Cokies, it further cemented Smithfield's in their heart as their answer to Yankee fast food. The company grew exponentially into the 1940's, with the company's 1940 internal report showing 67 operational locations across the Carolinas. So next time you're in Carolina, make sure to stop at Smithfield's for "Slow Food Done Quick!"

The Stop n' Serve Safety Officers for Smithfield's North Carolina locations, circa 1940

.jpg)

A Smithfield's Stop n' Serve in downtown Charlotte, with a garage attached for further customer convenience (1939)

Armed restaurant officers is bizzare but also completely inline for Madness. Please tell me Smithfield looks like Colonel Sanders

(Some of the stuff Sanders and KFC have done otl would fit into WMIT without batting an eye)

(Some of the stuff Sanders and KFC have done otl would fit into WMIT without batting an eye)

Armed restaurant officers is bizzare but also completely inline for Madness. Please tell me Smithfield looks like Colonel Sanders

(Some of the stuff Sanders and KFC have done otl would fit into WMIT without batting an eye)

He's a younger fella now, but maybe if I write a follow up on them in the Oswald era he could be Colonel

Unrelated, but the next chapter is gonna be a hopefully detailed overview of Carolina in Africa!

I see the next Chancellor trying to diversify the economy away from the export model. Also, the Smithfield's will probably also have free coffee for the local OPV and police to discourage 'troublemakers'.

The following is my first bio and character study for the expanded Madness-verse. I hope you enjoy.

The following is verbatim from a multi-part pamphlet entitled Yank Levy (1897-1940): The Pinnacle Mercenary, by American writer and historian Julius Robert Hendrickson Jr., published by Lewis City Historical Press in 1960, part of series of pamphlets and booklets entitled Pinnacle Heroes: Past and Present.

Jonathan Franklin Moses Levy was born on Tuesday, October 5, 1897, in Hamilton, Ontario, Republican Union of America to Samuel Levy, a tailor and “horse doctor” and his wife Sarah Pollock, both of whom were part a Jewish family that had been in the Republican Union for a number of years. The young Levy, known to his friends and family as “Jack”, grew up in Hamilton for the very first years of his life, along with his nine other siblings. As a young child, Jack was a sickly child. As a result, Jack Levy became a Boy Scout at age ten and a boxer at age eleven. The Levy family was lower class and relatively poor, and as a result, during his pre-teen and teenaged years, the young Jack Levy spent much of his time on the streets of Hamilton hawking random items, delivering items for local business and doing odd jobs for money, getting in fights with neighborhood bullies and other young boys working for rival businesses, as well as gangsters of numerous ethnicities that lived in the Inferior Ghetto of Hamilton. It was in these fights that the young Jonathan Levy learned the arts of pugilism and self-defense, skills which would serve him well in later life. In 1910, when Jack was thirteen years old, Samuel Levy, once a devout and practicing Jew, officially converted to American Fundamentalist Christianity, and he converted the rest of the family as well, including the young Jack.

A photograph of Hamilton, Ontario, 1900

In November, 1911, things for the Levy family were about to change forever. On November 22, 1911, the Republican Union of America declared war on the Empire of Europa and thus entered the Great World War. With the Republican Union sharing a border with the Kingdom of Quebec and Europan Canada, the Republican Union was ready to invade the Imperial lands of North America, and with Hamilton, Ontario only located a few hundred or so miles from the front-lines, the war was about to effect the Levy family in a very important way. Soon after the war began, the armies of the Union began pouring into Ontario in an effort to prepare for their invasion of Quebec and to defend against any preemptive attacks by the Europans, Kebeckers and Canadians. It was against this backdrop that Hamilton became immensely crowded with the innumerable brave soldiers of Uncle Sam, many from camps located outside of the city, but also many temporarily keeping quarters within the city. With all of these soldiers in Hamilton and with the excitement over the war against Europa, the fourteen year-old Jack Levy became enamored with the American military might and prowess, and it became his dream to one day became a soldier in the American army itself. As he recounted it himself in his autobiography, Life of a Pinnacle Fighter;

“I became acquainted with the soldiers of the American army in November and December of nineteen-hundred and eleven, when I was just a young teenager. I even spoke with a few soldiers and talked to them about their fight against the northern heathens of Keybeck and Canada. [….] I was enamored. It all simply amazed me. [….] I spoke to my father about it all, about how I wanted to grow up and became a soldier as soon as I became old enough to enlist [at age seventeen]. Alas, my father Samuel was firmly against such a proposition. “Son, no way on Jehovah’s Great Green Earth are you going to fight in the army. As much as I respect and admire our boys in the army, I won’t let you sacrifice your life.” Such an answer disappointed me immensely, and I vowed that one day I would join the army in spite of my father’s misguided wishes.”

American soldiers on parade in Hamilton, Ontario, November, 1911

Before long, the war would come to affect the Levy family even more. In March, 1912, by air raids by the Quebecois Air Force took place over numerous cities throughout Ontario, including Hamilton. During one such air raid over Hamilton, on March 30, 1912, much off the city was set ablaze by fires coming from incendiary bombs dropped by the aero planes of the Quebecois fighter planes. Numerous buildings were destroyed during the air raid, including the home of the Levy family. In fact, according to the army’s historical records, one of the Quebecois bombs landed just in front of the Levy family home, causing the home to collapse and immolate immediately. As this was happening, the young John Levy was in town selling random objects for a local general store named “Smith’s General Store”. As he heard the enemy bombs in the distance, he ran and hid in the basement of the store with the rest of the employees and the boss Robert Smith. Some hours after the raid ended, Levy was notified by his boss and members of the Hamilton Police Department that his parents and younger siblings had died the air raid. According to Levy from the same hitherto-quoted book; “Upon hearing the news, I, wearing a plaid overall with one strap across from my right shoulder, a blue sweater and a worn-out grey plaid cap, sat on the crate, put my head in my hands with my shoulders on my knees and then balled out and cried like I had had before or since. As I did so, the policemen, one named Smithson and the other Kruger, each came around me, Kruger patting me on the back and Smithson saying everything was going to be okay. In that moment, I could not believe him.”

Jack was then sent to live with his unmarried paternal uncle Herschel in New Berlin, Ontario. However, as much as Jack loved his uncle, the arrangement only lasted for a few months and before long, young Jack had made a fateful decision. In October, 1912, just after his fifteenth birthday, Jack ran away from his family with, in his own words from his memoir, “nothing but a bindle of some essential possessions and the clothes on my back. I walked for a long time on numerous roads until I made my way to Toronto. [….] I went to go find an army recruiting station, and after some hours I found one across the street from the Governor’s Mansion. I went over to the recruiting station and signed up to fight in the infantry of our grand republican army. The only obstacle was that I was too young to enlist in the armed forces. Luckily for me I was a smart kid and I had my Rounders Bases covered. The recruiter, a young clean-shaven man in spectacles, speaking in a Nordic accent, said “Your name?” I replied, “John Abraham Oppenheimer” after which I wrote said name down on the recruitment form. The man then asked “Your date of birth?” I then stayed silent and wrote down the following date; October 5, 1895. [….] I confess. I lied about my age to get into the army. I know, under most circumstances, it’s a sin to lie, but I did it for a noble purpose, to fight for the Republican Union, the New Jerusalem, and to do my duty to my nation and to my Israelite ancestors to help bring about the rise of God’s kingdom on this Earth.”

Almost immediately after signing up for the army, young Jack was sent to the front-lines of battle as a member of the 10th Ontario Infantry against the Europan, Canadian and Quebecois armies in Quebec. After only a few months, Jack had already seen a lot of action against the enemy. While most spent doing menial tasks such as peeling potatoes, cooking food, organizing rations and cleaning encampments, Jack also did see a lot of front-line action. “During my first battle, in March of 1913, just after the start of spring, I and my patriot-comrades were marching through a small town in Keybeck, when some blue-coated Beckie soldiers came out of some ruined building and lunged at us with daggers. Some of my patriot-comrades were stabbed to death, others fought for dear life, but I ran off and then picked off each of the Beckie soldiers with a coffee-grinder hidden behind some rubble. [….] When it was all said and done, me, just a teenager, killed all seven of the Beckie soldiers. Two of our own were killed, while three others had to be sent to the medic.” In other battles, Levy also showed himself to be a brave if often overenthusiastic soldier. Jack was also known to “shoot like crazy at the Beckie enemy with two pistols on each side of his holster”, according to an officer by the name of Bradley were served in the 10th Ontario.

Men of the 10th Ontario, 1912

After only over half a year fighting in Quebec, in May, 1913, Jack Levy’s unit, the 10th Ontario Infantry, was sent west to the Californian Front as part of a sees reinforcements for General Joe Steele’s Army of the West. Soon after arriving by train in Salvation Springs, Lewisland, and after some training, Jack Levy and the rest of the 10th Ontario made their way to the frontlines of battle to meet up the armies of Joe Steele deep in the heart of California. From May to September, 1913, Jack Levy participated in some of the most climactic and intense battles of the Californian front. In these battles, like the battles in Ontario, the teenaged Jack Levy proved himself to a brave, enthusiastic, though and capable soldier and fighter. In his own words; “In Old California, I fought even harder against the Callies then even against the Beckies. [….] The men of California were tough and hardened by the harsh climate and terrain of their nation, to mention the threat of our invasion. [….] This was so sweat for me. In every battle against them I made sure to fire as many rounds as I could, and in doing so may feel before my eyes like the metal ducks on a carnival game.” One officer named Mitchell Hummel even stated that “Young Levy was like a human coffee-grinder.” In August, 1913, shortly before the Battle of Sacrament, during which Levy also fought bravely under fire, Levy even got to meet Joe Steele himself as Steele was inspected the troops before battle. “I remember meeting Joe Steele, and it was one of the most memorable moments of my life. [….] [As he was inspecting the troops] Steele came up to and me and said “You like a bit young for the service lad, but you’re a brave pinnacle lad nonetheless.” We then shook hands. “Thanks sir. It’s an honor to meet you.” I said. “Your Welcome. I can tell you are destined for greatness.” He responded.”

American soldiers on the march in eastern California

American Infantrymen some days before the Battle of Sacrament, August, 1913

After the fall of California on September 20, 1913, the teenaged Jack Levy spent a few months on occupation duty, after which he was honorably discharged in November, 1913. Not long afterwards, Jack, wanting to see more battle and “craving more adventure” joined a unit of “Irregular Volunteers”, a ragtag group of miscreants, ex-cons and other impoverished Betters who were offering their services to the Army and Marines in their invasion and conquest of the European Pacific colonies. Thus, the sixteen year-old Levy had become a mercenary for the first time in his military career, and it would not be his last. In just a few weeks, Jack Levy arrived in Honolulu, Hawaii, after which he and the Irregular Volunteers headed with the RU Marines to invade the Bonaparte Islands throughout December 1913 and until May, 1914. During these battles, Levy saw intense jungle combat, and often hand to hand combat, with not only French, Spanish, Italian and Flemish Europan colonial troops using obsolete rifles and pistols, but also Micronesian tribal soldiers in the service of the European colonial armies wielding clubs and axes. In May, 1914, Levy was sent back to Oregon by the RU Marines, as the volunteers were no longer of use to them.

American soldiers in Oregon ready to shipped to Micronesia, 1913

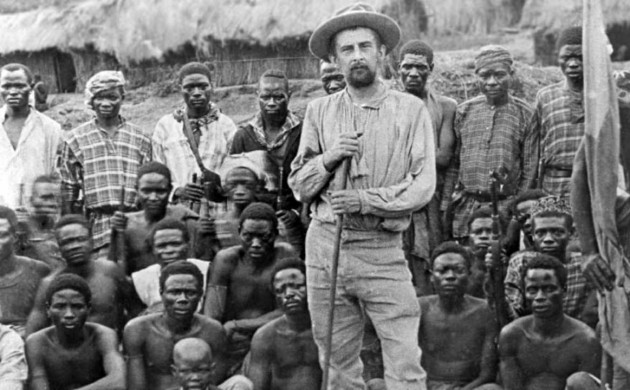

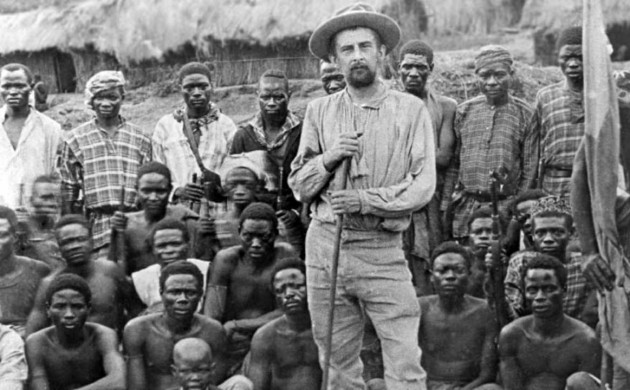

European Colonial Soldiers and Native Soldiers in European Micronesia, 1913

Soon after his return from Micronesia, in June, 1914, Jack was honorably discharged from the army. After being discharged from the army, Jack Levy might his way to Oregon with a small caravan of other recently discharged veterans. After arriving in Linkville, Oregon, Levy bought an apartment in a small apartment building and began to work as a delivery man for Sweet Victory Soda, a job in which he would drive around an autocarriage full of crates of the drink and then deliver them to local stores and homes all around town. However, Jack was quickly becoming bored with his life as a delivery boy. As Levy wrote; “Truth be told, I needed to find another war to fight in.”

Linkville, Oregon, 1909

Yank Levy: The Pinnacle Mercenary

Part One

Jack "Yank" Levy, photographed in the Dutch East Indies, circa 1930

Part One

Jack "Yank" Levy, photographed in the Dutch East Indies, circa 1930

The following is verbatim from a multi-part pamphlet entitled Yank Levy (1897-1940): The Pinnacle Mercenary, by American writer and historian Julius Robert Hendrickson Jr., published by Lewis City Historical Press in 1960, part of series of pamphlets and booklets entitled Pinnacle Heroes: Past and Present.

Jonathan Franklin Moses Levy was born on Tuesday, October 5, 1897, in Hamilton, Ontario, Republican Union of America to Samuel Levy, a tailor and “horse doctor” and his wife Sarah Pollock, both of whom were part a Jewish family that had been in the Republican Union for a number of years. The young Levy, known to his friends and family as “Jack”, grew up in Hamilton for the very first years of his life, along with his nine other siblings. As a young child, Jack was a sickly child. As a result, Jack Levy became a Boy Scout at age ten and a boxer at age eleven. The Levy family was lower class and relatively poor, and as a result, during his pre-teen and teenaged years, the young Jack Levy spent much of his time on the streets of Hamilton hawking random items, delivering items for local business and doing odd jobs for money, getting in fights with neighborhood bullies and other young boys working for rival businesses, as well as gangsters of numerous ethnicities that lived in the Inferior Ghetto of Hamilton. It was in these fights that the young Jonathan Levy learned the arts of pugilism and self-defense, skills which would serve him well in later life. In 1910, when Jack was thirteen years old, Samuel Levy, once a devout and practicing Jew, officially converted to American Fundamentalist Christianity, and he converted the rest of the family as well, including the young Jack.

A photograph of Hamilton, Ontario, 1900

In November, 1911, things for the Levy family were about to change forever. On November 22, 1911, the Republican Union of America declared war on the Empire of Europa and thus entered the Great World War. With the Republican Union sharing a border with the Kingdom of Quebec and Europan Canada, the Republican Union was ready to invade the Imperial lands of North America, and with Hamilton, Ontario only located a few hundred or so miles from the front-lines, the war was about to effect the Levy family in a very important way. Soon after the war began, the armies of the Union began pouring into Ontario in an effort to prepare for their invasion of Quebec and to defend against any preemptive attacks by the Europans, Kebeckers and Canadians. It was against this backdrop that Hamilton became immensely crowded with the innumerable brave soldiers of Uncle Sam, many from camps located outside of the city, but also many temporarily keeping quarters within the city. With all of these soldiers in Hamilton and with the excitement over the war against Europa, the fourteen year-old Jack Levy became enamored with the American military might and prowess, and it became his dream to one day became a soldier in the American army itself. As he recounted it himself in his autobiography, Life of a Pinnacle Fighter;

“I became acquainted with the soldiers of the American army in November and December of nineteen-hundred and eleven, when I was just a young teenager. I even spoke with a few soldiers and talked to them about their fight against the northern heathens of Keybeck and Canada. [….] I was enamored. It all simply amazed me. [….] I spoke to my father about it all, about how I wanted to grow up and became a soldier as soon as I became old enough to enlist [at age seventeen]. Alas, my father Samuel was firmly against such a proposition. “Son, no way on Jehovah’s Great Green Earth are you going to fight in the army. As much as I respect and admire our boys in the army, I won’t let you sacrifice your life.” Such an answer disappointed me immensely, and I vowed that one day I would join the army in spite of my father’s misguided wishes.”

American soldiers on parade in Hamilton, Ontario, November, 1911

Before long, the war would come to affect the Levy family even more. In March, 1912, by air raids by the Quebecois Air Force took place over numerous cities throughout Ontario, including Hamilton. During one such air raid over Hamilton, on March 30, 1912, much off the city was set ablaze by fires coming from incendiary bombs dropped by the aero planes of the Quebecois fighter planes. Numerous buildings were destroyed during the air raid, including the home of the Levy family. In fact, according to the army’s historical records, one of the Quebecois bombs landed just in front of the Levy family home, causing the home to collapse and immolate immediately. As this was happening, the young John Levy was in town selling random objects for a local general store named “Smith’s General Store”. As he heard the enemy bombs in the distance, he ran and hid in the basement of the store with the rest of the employees and the boss Robert Smith. Some hours after the raid ended, Levy was notified by his boss and members of the Hamilton Police Department that his parents and younger siblings had died the air raid. According to Levy from the same hitherto-quoted book; “Upon hearing the news, I, wearing a plaid overall with one strap across from my right shoulder, a blue sweater and a worn-out grey plaid cap, sat on the crate, put my head in my hands with my shoulders on my knees and then balled out and cried like I had had before or since. As I did so, the policemen, one named Smithson and the other Kruger, each came around me, Kruger patting me on the back and Smithson saying everything was going to be okay. In that moment, I could not believe him.”

Jack was then sent to live with his unmarried paternal uncle Herschel in New Berlin, Ontario. However, as much as Jack loved his uncle, the arrangement only lasted for a few months and before long, young Jack had made a fateful decision. In October, 1912, just after his fifteenth birthday, Jack ran away from his family with, in his own words from his memoir, “nothing but a bindle of some essential possessions and the clothes on my back. I walked for a long time on numerous roads until I made my way to Toronto. [….] I went to go find an army recruiting station, and after some hours I found one across the street from the Governor’s Mansion. I went over to the recruiting station and signed up to fight in the infantry of our grand republican army. The only obstacle was that I was too young to enlist in the armed forces. Luckily for me I was a smart kid and I had my Rounders Bases covered. The recruiter, a young clean-shaven man in spectacles, speaking in a Nordic accent, said “Your name?” I replied, “John Abraham Oppenheimer” after which I wrote said name down on the recruitment form. The man then asked “Your date of birth?” I then stayed silent and wrote down the following date; October 5, 1895. [….] I confess. I lied about my age to get into the army. I know, under most circumstances, it’s a sin to lie, but I did it for a noble purpose, to fight for the Republican Union, the New Jerusalem, and to do my duty to my nation and to my Israelite ancestors to help bring about the rise of God’s kingdom on this Earth.”

Almost immediately after signing up for the army, young Jack was sent to the front-lines of battle as a member of the 10th Ontario Infantry against the Europan, Canadian and Quebecois armies in Quebec. After only a few months, Jack had already seen a lot of action against the enemy. While most spent doing menial tasks such as peeling potatoes, cooking food, organizing rations and cleaning encampments, Jack also did see a lot of front-line action. “During my first battle, in March of 1913, just after the start of spring, I and my patriot-comrades were marching through a small town in Keybeck, when some blue-coated Beckie soldiers came out of some ruined building and lunged at us with daggers. Some of my patriot-comrades were stabbed to death, others fought for dear life, but I ran off and then picked off each of the Beckie soldiers with a coffee-grinder hidden behind some rubble. [….] When it was all said and done, me, just a teenager, killed all seven of the Beckie soldiers. Two of our own were killed, while three others had to be sent to the medic.” In other battles, Levy also showed himself to be a brave if often overenthusiastic soldier. Jack was also known to “shoot like crazy at the Beckie enemy with two pistols on each side of his holster”, according to an officer by the name of Bradley were served in the 10th Ontario.

Men of the 10th Ontario, 1912

After only over half a year fighting in Quebec, in May, 1913, Jack Levy’s unit, the 10th Ontario Infantry, was sent west to the Californian Front as part of a sees reinforcements for General Joe Steele’s Army of the West. Soon after arriving by train in Salvation Springs, Lewisland, and after some training, Jack Levy and the rest of the 10th Ontario made their way to the frontlines of battle to meet up the armies of Joe Steele deep in the heart of California. From May to September, 1913, Jack Levy participated in some of the most climactic and intense battles of the Californian front. In these battles, like the battles in Ontario, the teenaged Jack Levy proved himself to a brave, enthusiastic, though and capable soldier and fighter. In his own words; “In Old California, I fought even harder against the Callies then even against the Beckies. [….] The men of California were tough and hardened by the harsh climate and terrain of their nation, to mention the threat of our invasion. [….] This was so sweat for me. In every battle against them I made sure to fire as many rounds as I could, and in doing so may feel before my eyes like the metal ducks on a carnival game.” One officer named Mitchell Hummel even stated that “Young Levy was like a human coffee-grinder.” In August, 1913, shortly before the Battle of Sacrament, during which Levy also fought bravely under fire, Levy even got to meet Joe Steele himself as Steele was inspected the troops before battle. “I remember meeting Joe Steele, and it was one of the most memorable moments of my life. [….] [As he was inspecting the troops] Steele came up to and me and said “You like a bit young for the service lad, but you’re a brave pinnacle lad nonetheless.” We then shook hands. “Thanks sir. It’s an honor to meet you.” I said. “Your Welcome. I can tell you are destined for greatness.” He responded.”

American soldiers on the march in eastern California

American Infantrymen some days before the Battle of Sacrament, August, 1913

After the fall of California on September 20, 1913, the teenaged Jack Levy spent a few months on occupation duty, after which he was honorably discharged in November, 1913. Not long afterwards, Jack, wanting to see more battle and “craving more adventure” joined a unit of “Irregular Volunteers”, a ragtag group of miscreants, ex-cons and other impoverished Betters who were offering their services to the Army and Marines in their invasion and conquest of the European Pacific colonies. Thus, the sixteen year-old Levy had become a mercenary for the first time in his military career, and it would not be his last. In just a few weeks, Jack Levy arrived in Honolulu, Hawaii, after which he and the Irregular Volunteers headed with the RU Marines to invade the Bonaparte Islands throughout December 1913 and until May, 1914. During these battles, Levy saw intense jungle combat, and often hand to hand combat, with not only French, Spanish, Italian and Flemish Europan colonial troops using obsolete rifles and pistols, but also Micronesian tribal soldiers in the service of the European colonial armies wielding clubs and axes. In May, 1914, Levy was sent back to Oregon by the RU Marines, as the volunteers were no longer of use to them.

American soldiers in Oregon ready to shipped to Micronesia, 1913

European Colonial Soldiers and Native Soldiers in European Micronesia, 1913

Soon after his return from Micronesia, in June, 1914, Jack was honorably discharged from the army. After being discharged from the army, Jack Levy might his way to Oregon with a small caravan of other recently discharged veterans. After arriving in Linkville, Oregon, Levy bought an apartment in a small apartment building and began to work as a delivery man for Sweet Victory Soda, a job in which he would drive around an autocarriage full of crates of the drink and then deliver them to local stores and homes all around town. However, Jack was quickly becoming bored with his life as a delivery boy. As Levy wrote; “Truth be told, I needed to find another war to fight in.”

Linkville, Oregon, 1909

Although I will be writing on Africa soon, the main thread's CoCorea meme has actually inspired me to write some Carolina-Korea stuff here. Here's my first installment

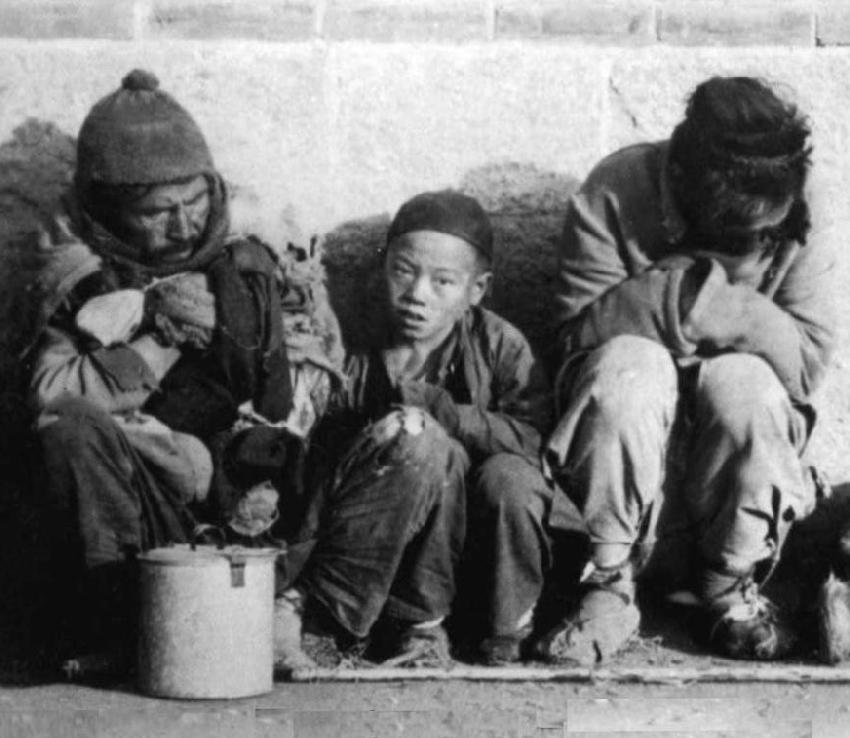

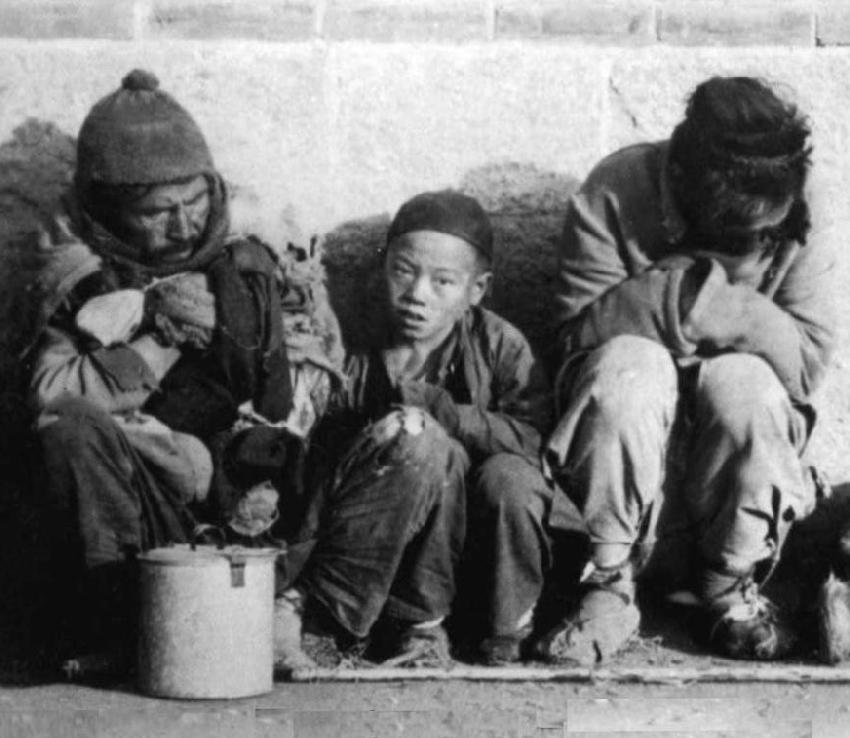

The first mission trip to Korea sent by the Presbyterian Church of the Confederation of the Carolinas landed in Busan on April 17th, 1874. Comprised of 150 men, women, and children, it was the single largest group of missionaries ever sent into Asia by the Carolinians. They were led by Reverend Samuel Robert Howe of Charlotte, North Carolina. Reverend Howe was a wise man, who in preparation for the trip taught himself fluent Mandarin Chinese. When questioned on his use of "that yellow devil tongue," the Reverend would smile and pull out his map of the world. He would direct his questioners to Korea's proximity to China, and then exclaim the same speech "We are sailing for an uncharted land my dear fellow. Not a single member of the English-speaking races has yet set foot in this mysterious kingdom. Therefore, it is foolish to assume they will understand our beloved mother tongue. However, given the territory's proximity to the lands of the heathenish Chinese race, it seems likely that at least the educated among them speak Chinese. I have no love for China or Chinese, but I do believe that if we can't communicate with these fellers, our ability to spread the Gospel will be quite severely limited." This explanation was rational enough to sway just about everyone who heard it, and eventually the questioning ended. The expedition left for Busan a year before their arrival, to much jubilation from the Carolinian public. The nation was feeling an upsurge in national confidence thanks to the recent colonization of Jacksonland and the still fresh memory of West Carolina's reclamation, and the Great Disturbance had yet to come. The overwhelming majority of Cokies were unceasingly confident that the march of their civilization would continue without fail.

The journey of this first expedition was long and arduous. The Panama Canal did not yet exist, so the missionaries had to travel from Carolina to German Africa, then Jacksonland, then a tense stop off in the French Raj, followed by a couple final stops in Dutch Asia. When the missionaries arrived, they were greeted by a hostile "platoon" of armored Korean soldiers. The men in the party had their guns drawn, and it appeared a disastrous bloodbath would ensue. However, Reverend Howe quickly put his Chinese training to work, and managed to talk down the soldiers. He was apprehended by the troops and brought before Jeon Yuk, a senior official for the Joeson Dynasty. The two conversed for several hours and Reverend Howe managed to convince Jeon to allow his missionaries to station themselves in Busan. From there, the missionaries began learning Korean and Chinese under Howe's direction, preparing to print the Presbyterian Bible in both languages. After roughly another year, the missionaries produced the first Korean and Chinese language Presbyterian Bibles. By 1878, the missionaries had printed over 20,000 bibles, and had also set up an English language school to "civilize the locals." There were clashes with the Joeson authorities, but the dynasty had been in a state of stagnation and decline for years, and the increasing Christianization of the local Joeson authorities meant that the missionaries could continue their work relatively unimpeded. However, the relatively small number of isolated missionaries could only do so much. Nonetheless, this first wave of missionaries laid down the foundation for later work.

The Reverend Samuel Robert Howe and his family, shortly before their 1873 departure for Korea.

The late 1890's would see the start of a new wave of Carolinian missionary activity. The rise of Custer, the annexation of the Goodyear Islands, and the rise of Fascist Australia and Holy Nippon made travel to and from Korea much easier. Now, Cokie missionaries could hop on a train in Carolina, speed to Oregon or annexed Mexico in a couple of weeks, and then pop onto a steamer and spend a couple months traveling to Nippon before finally heading to Korea. The creation of the Great Canal in former Panama in 1892 made travel even easier, allowing a Cokie missionary to hop on a ship in Charleston and be in Korea in a short couple of months. When combined with the economic boom after the Great Disturbance and a continued desire to prove Carolinian strength, the result was thousands upon thousands of Carolinian missionaries flooding into Korea. Armed with handy dandy pocket Korean-English dictionaries printed by the original batch of missionaries, Korean language bibles, and of course sidearms, the new wave of missionaries would land in Busan and then move rapidly towards Inchon, Seoul, Daegu, and even as far North as Pyongyang, a place surprisingly receptive to the missionaries. With a flood of resources and manpower coming in, the Cokies set to work erecting churches and schools in rapid fashion. Although the churches weren't quite as popular (for reasons about to be explored) the schools most definitely were. Thousands of Korean peasants sent their children to be educated by missionaries, who taught them Carolinian English, modern agricultural techniques, and other useful things. Of course, not everyone appreciated the foreign intruders.

The Korean people were and are famously xenophobic. Korea is known as the Hermit Kingdom for a reason, and it was certainly not the friendly kind of hermit, but rather the angry type who yells "get off my lawn" before opening fire on small children and animals. By 1900, the Joeson Dynasty and traditional Korean shamans and Confucian leaders, as well as a good portion of the peasantry, were extremely angry at the swaggering foreigners. In the almost 12 years between 1900 and Carolina's entry into the Great Patriotic War in November of 1911, there were 20 Carolinian military interventions in Korea. These interventions are mostly beyond the scope of this chapter, but they were almost always incited by attacks on Carolinian missionaries, and ranged from small gunboat actions to proper invasions. These interventions, and the growth of the missionary movement, were put on hold by the Great War, and scarcely resumed before the Germanian Civil War drew in an enraged Carolinian populace. Thus, 1911 is considered the end of the second wave of Cokie missionary endeavor. Missionary presence in Korea by 1911 numbered well into the thousands, but without access to Cokie military resources their influence was more limited than it had been previously.

The semi-triumphant end of the Germanian Civil War opened the door for the third wave of Carolinian missionary activity. With newly acquired Yonderland and East Carolina in tow, it was cheaper than ever for Carolinian missionaries to launch themselves at Korea. Korea remained by far the largest destination for Cokie missionaries, even exceeding the African territories. The 1920's and 1930's saw more Cokie missionary activity than ever, and this was accompanied by another two dozen military interventions until the fateful year of 1932, where with the help of local collaborators, Korea would be changed forever. Before and after that fateful date, the Cokies continued to influence the Korean population, and the result speak for themselves. By the outbreak of the war between the Union and the Neutrality Pact in 1936, a sizable minority of Korea was fluent in Carolinian English. Furthermore, roughly 40% of the Korean population were professing Presbyterians. As the famous Cokie war anthem goes, the missionaries vowed to work and fight "Till the Heathens are defeated, Till the Lord's Work is completed."

The CNS Libertas, a gunboat used in several Cokie interventions in Korea

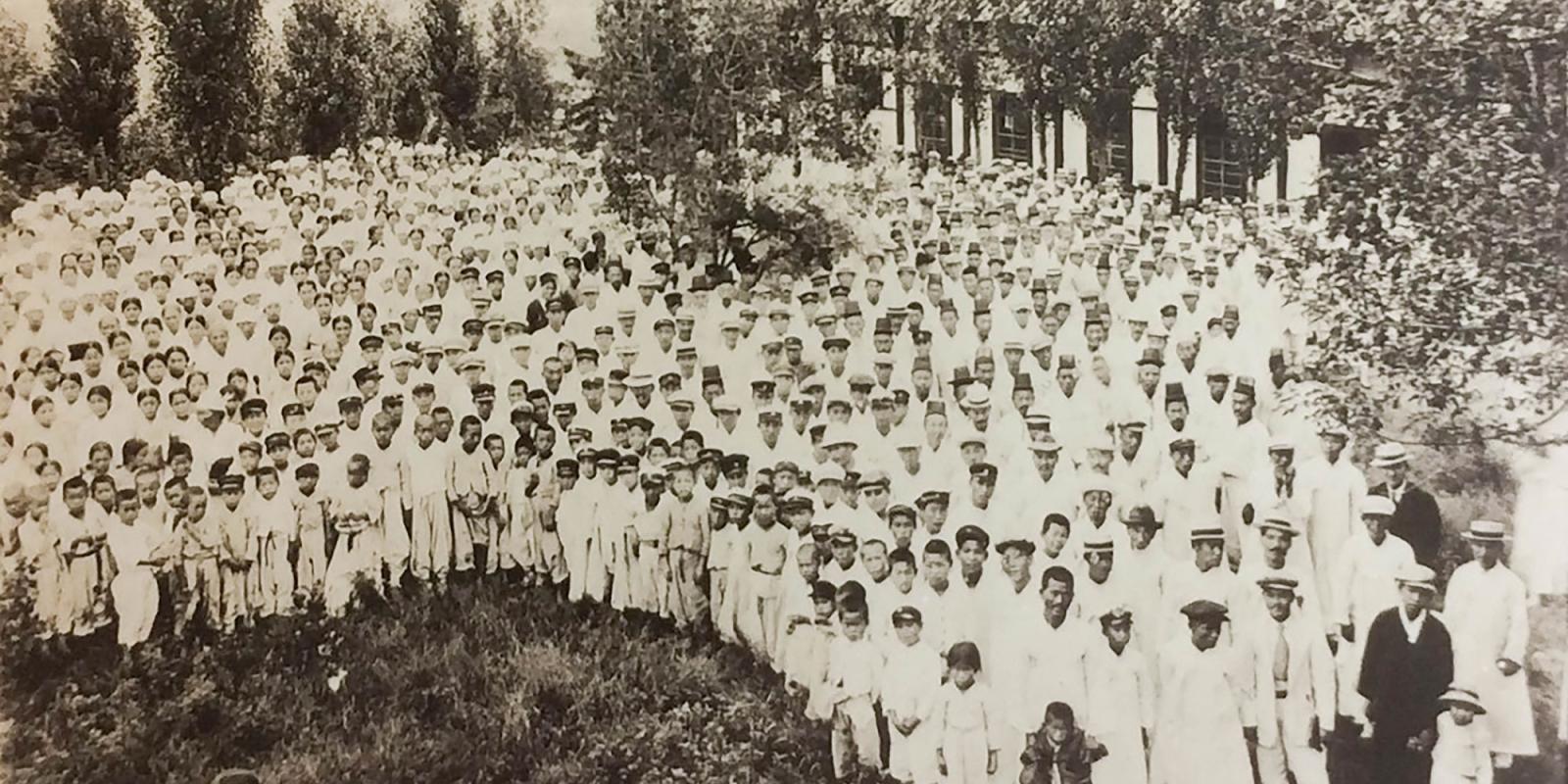

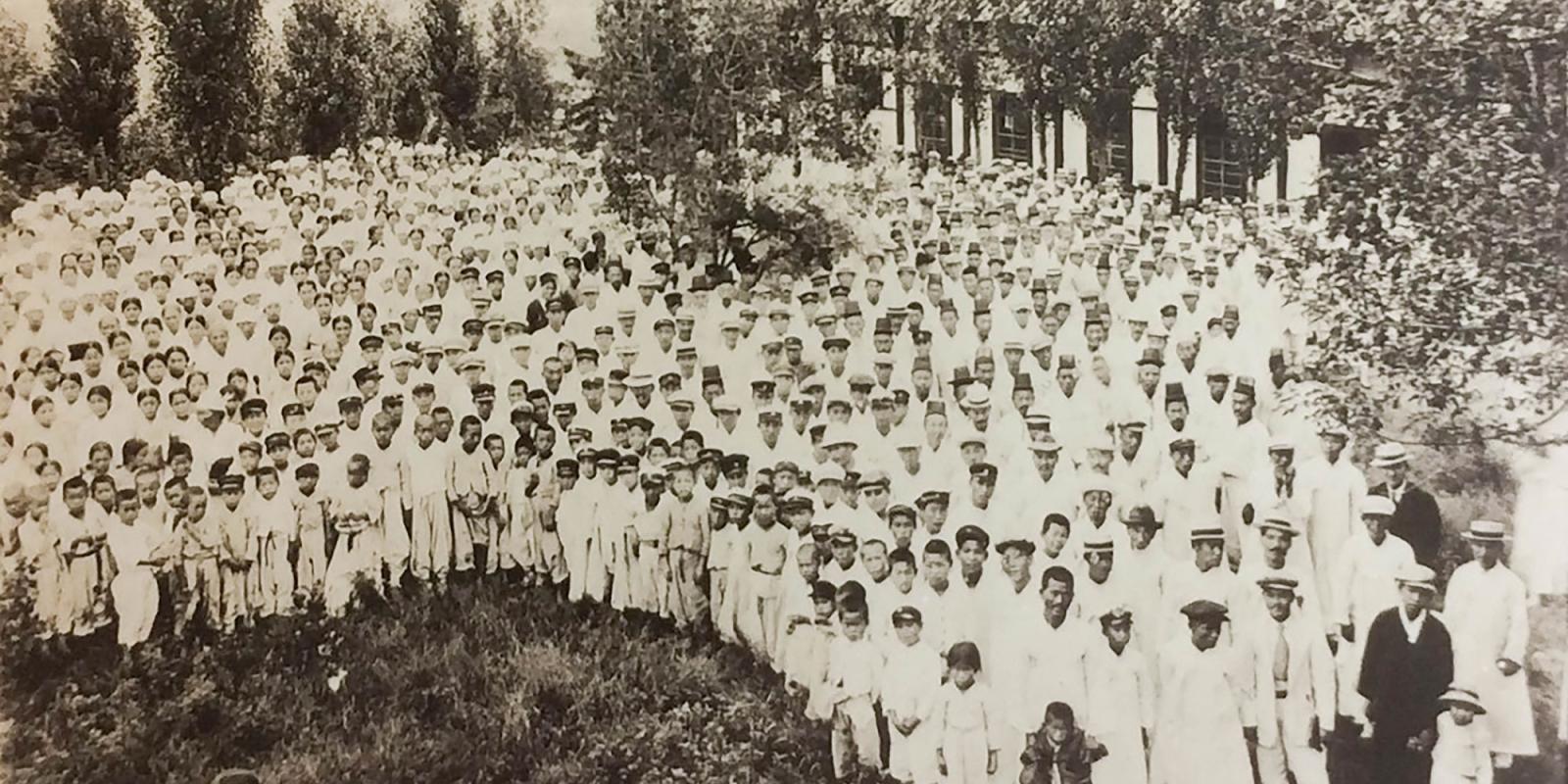

Korean Presbyterians in Pyongyang "The Jerusalem of the East" circa 1905

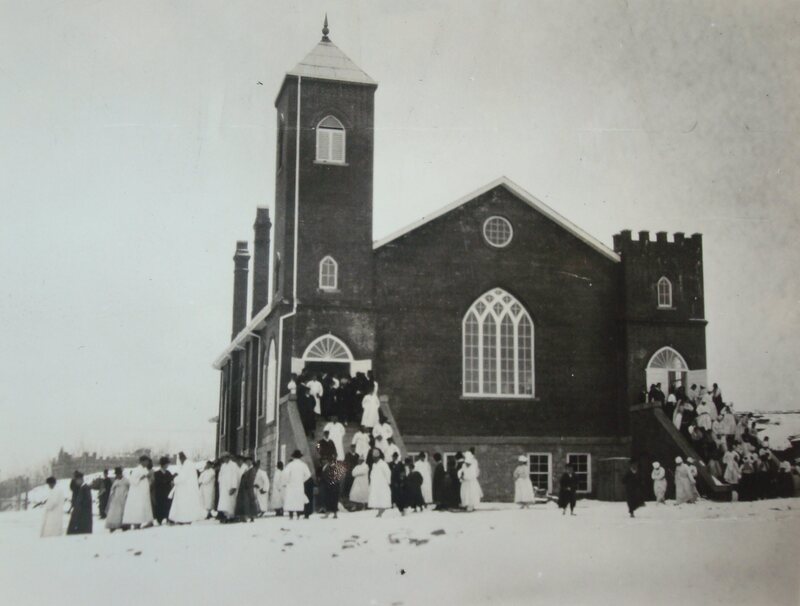

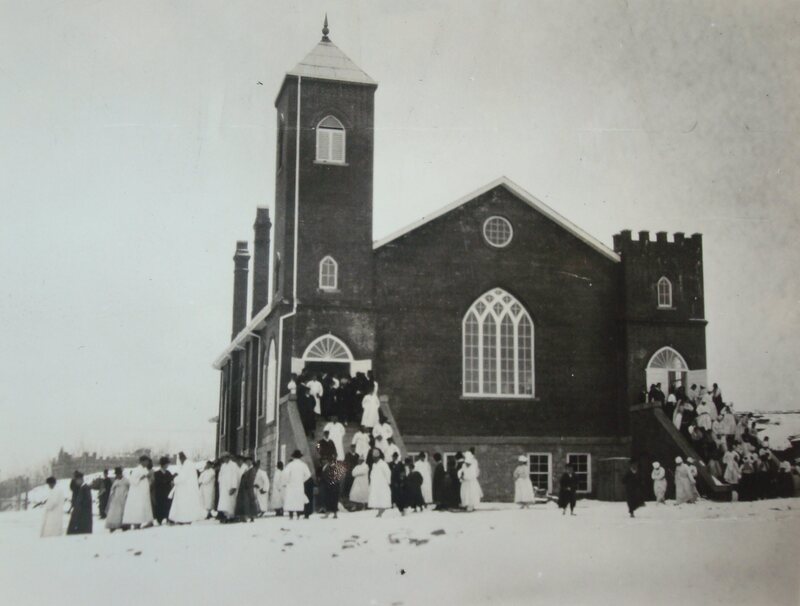

First Presbyterian Church in Pyongyang, 1909

Hark the Sound of Missionary Voices: Carolinian Missionaries in Korea

Missionaries from the First Presbyterian Church of Nashville (1898)

When most people think of Free World influence in Asia, they think about Australia, the RUA, and the Dutch. Australia is actually within the realm of Asia and Oceania, making it a fairly obvious choice. The Dutch have built a massive empire in the region, containing the Philippines, Indochina, and other territories. Of course, the Yankee behemoth's history of opening and then conquering Nippon is infamous. However, the Carolinians exerted a surprising amount of influence in Asia. Cokie mercenaries helped exterminate Australian aboriginals and police the Dutch Empire, while Cokie traders, soldiers, and diplomats established a substantial presence in Holy Nippon and its successor Yankee states. However, there is no place where Carolinian influence was more obvious than the Hermit Kingdom of Korea. Although the Cokies did not colonize the Peninsula, they were by far the most active foreign power there. Given the fact that the alternatives were colonization by Europa, colonization by the Dutch, annexation by China, annexation by Russia, or potential genocide and annexation by the Union, Korea got off very easily. In this segment, we will explore the impact of Carolinian missionaries on Korea.

Missionaries from the First Presbyterian Church of Nashville (1898)

The first mission trip to Korea sent by the Presbyterian Church of the Confederation of the Carolinas landed in Busan on April 17th, 1874. Comprised of 150 men, women, and children, it was the single largest group of missionaries ever sent into Asia by the Carolinians. They were led by Reverend Samuel Robert Howe of Charlotte, North Carolina. Reverend Howe was a wise man, who in preparation for the trip taught himself fluent Mandarin Chinese. When questioned on his use of "that yellow devil tongue," the Reverend would smile and pull out his map of the world. He would direct his questioners to Korea's proximity to China, and then exclaim the same speech "We are sailing for an uncharted land my dear fellow. Not a single member of the English-speaking races has yet set foot in this mysterious kingdom. Therefore, it is foolish to assume they will understand our beloved mother tongue. However, given the territory's proximity to the lands of the heathenish Chinese race, it seems likely that at least the educated among them speak Chinese. I have no love for China or Chinese, but I do believe that if we can't communicate with these fellers, our ability to spread the Gospel will be quite severely limited." This explanation was rational enough to sway just about everyone who heard it, and eventually the questioning ended. The expedition left for Busan a year before their arrival, to much jubilation from the Carolinian public. The nation was feeling an upsurge in national confidence thanks to the recent colonization of Jacksonland and the still fresh memory of West Carolina's reclamation, and the Great Disturbance had yet to come. The overwhelming majority of Cokies were unceasingly confident that the march of their civilization would continue without fail.

The journey of this first expedition was long and arduous. The Panama Canal did not yet exist, so the missionaries had to travel from Carolina to German Africa, then Jacksonland, then a tense stop off in the French Raj, followed by a couple final stops in Dutch Asia. When the missionaries arrived, they were greeted by a hostile "platoon" of armored Korean soldiers. The men in the party had their guns drawn, and it appeared a disastrous bloodbath would ensue. However, Reverend Howe quickly put his Chinese training to work, and managed to talk down the soldiers. He was apprehended by the troops and brought before Jeon Yuk, a senior official for the Joeson Dynasty. The two conversed for several hours and Reverend Howe managed to convince Jeon to allow his missionaries to station themselves in Busan. From there, the missionaries began learning Korean and Chinese under Howe's direction, preparing to print the Presbyterian Bible in both languages. After roughly another year, the missionaries produced the first Korean and Chinese language Presbyterian Bibles. By 1878, the missionaries had printed over 20,000 bibles, and had also set up an English language school to "civilize the locals." There were clashes with the Joeson authorities, but the dynasty had been in a state of stagnation and decline for years, and the increasing Christianization of the local Joeson authorities meant that the missionaries could continue their work relatively unimpeded. However, the relatively small number of isolated missionaries could only do so much. Nonetheless, this first wave of missionaries laid down the foundation for later work.

The Reverend Samuel Robert Howe and his family, shortly before their 1873 departure for Korea.

The late 1890's would see the start of a new wave of Carolinian missionary activity. The rise of Custer, the annexation of the Goodyear Islands, and the rise of Fascist Australia and Holy Nippon made travel to and from Korea much easier. Now, Cokie missionaries could hop on a train in Carolina, speed to Oregon or annexed Mexico in a couple of weeks, and then pop onto a steamer and spend a couple months traveling to Nippon before finally heading to Korea. The creation of the Great Canal in former Panama in 1892 made travel even easier, allowing a Cokie missionary to hop on a ship in Charleston and be in Korea in a short couple of months. When combined with the economic boom after the Great Disturbance and a continued desire to prove Carolinian strength, the result was thousands upon thousands of Carolinian missionaries flooding into Korea. Armed with handy dandy pocket Korean-English dictionaries printed by the original batch of missionaries, Korean language bibles, and of course sidearms, the new wave of missionaries would land in Busan and then move rapidly towards Inchon, Seoul, Daegu, and even as far North as Pyongyang, a place surprisingly receptive to the missionaries. With a flood of resources and manpower coming in, the Cokies set to work erecting churches and schools in rapid fashion. Although the churches weren't quite as popular (for reasons about to be explored) the schools most definitely were. Thousands of Korean peasants sent their children to be educated by missionaries, who taught them Carolinian English, modern agricultural techniques, and other useful things. Of course, not everyone appreciated the foreign intruders.

The Korean people were and are famously xenophobic. Korea is known as the Hermit Kingdom for a reason, and it was certainly not the friendly kind of hermit, but rather the angry type who yells "get off my lawn" before opening fire on small children and animals. By 1900, the Joeson Dynasty and traditional Korean shamans and Confucian leaders, as well as a good portion of the peasantry, were extremely angry at the swaggering foreigners. In the almost 12 years between 1900 and Carolina's entry into the Great Patriotic War in November of 1911, there were 20 Carolinian military interventions in Korea. These interventions are mostly beyond the scope of this chapter, but they were almost always incited by attacks on Carolinian missionaries, and ranged from small gunboat actions to proper invasions. These interventions, and the growth of the missionary movement, were put on hold by the Great War, and scarcely resumed before the Germanian Civil War drew in an enraged Carolinian populace. Thus, 1911 is considered the end of the second wave of Cokie missionary endeavor. Missionary presence in Korea by 1911 numbered well into the thousands, but without access to Cokie military resources their influence was more limited than it had been previously.

The semi-triumphant end of the Germanian Civil War opened the door for the third wave of Carolinian missionary activity. With newly acquired Yonderland and East Carolina in tow, it was cheaper than ever for Carolinian missionaries to launch themselves at Korea. Korea remained by far the largest destination for Cokie missionaries, even exceeding the African territories. The 1920's and 1930's saw more Cokie missionary activity than ever, and this was accompanied by another two dozen military interventions until the fateful year of 1932, where with the help of local collaborators, Korea would be changed forever. Before and after that fateful date, the Cokies continued to influence the Korean population, and the result speak for themselves. By the outbreak of the war between the Union and the Neutrality Pact in 1936, a sizable minority of Korea was fluent in Carolinian English. Furthermore, roughly 40% of the Korean population were professing Presbyterians. As the famous Cokie war anthem goes, the missionaries vowed to work and fight "Till the Heathens are defeated, Till the Lord's Work is completed."

The CNS Libertas, a gunboat used in several Cokie interventions in Korea

Korean Presbyterians in Pyongyang "The Jerusalem of the East" circa 1905

First Presbyterian Church in Pyongyang, 1909

Last edited:

I wonder that their friends in the AFC, and thus, the President’s office would have to say in suddenly elevating the Korean people into Jehovah knows what status, considering they’re no Nippon in terms of religionists and social and economic sophistication, and the American’s mostly dismissing them as Infees. Maybe, they’ll argue that it was the Korean ships which tried to invade Japan in the name of the Mongol Horde, but still Korean nevertheless?

I wonder that their friends in the AFC, and thus, the President’s office would have to say in suddenly elevating the Korean people into Jehovah knows what status, considering they’re no Nippon in terms of religionists and social and economic sophistication, and the American’s mostly dismissing them as Infees. Maybe, they’ll argue that it was the Korean ships which tried to invade Japan in the name of the Mongol Horde, but still Korean nevertheless?

That's my big concern and something I'm going to try and address. Ideally, if this were all to work, they'd go down the same path as OTL Japan, which declared the Koreans part of their race and gave Korea preferential treatment in comparison to the rest of their empire (which isn't saying much).

Here's part two of the Cokie-Korea saga! I really think I'm building this to an awesome conclusion. I doubt it will be canon, but I really would like for it to be. Even if it isn't it's gonna be so damn hilarious and crazy that I won't care.

The first recorded use of Carolinian military force in Korea occurred on March 19th, 1900. A mob of Korean xenophobes lynched a missionary family in a small village along the Yalu. The CNS Freedom, CNS Cape Hatteras, and CNS Nathan Bedford Forrest were dispatched along with a contingent of 200 Carolinian Marines. The result was as predictable as it was bloody; the entire village was utterly exterminated. The international reaction was also predictable, as the entire Fascist sphere, alongside the Dutch, the Germans, the Scandinavians, and even the Catholics praised the Carolinians for "defending Christian civilization." Incidents similar to this would occur 7 more times between 1900 and 1904. The story was always the same; an angry village, dead missionaries, and an overwhelming Cokie response. May 1905 saw the first major problem in Korea. A drunk missionary accidentally told a prominent leader in Daegu "I would like to help fuck your sister," rather than "I would like to help find your sister," having flipped to the wrong page of his Korean-English dictionary after forgetting the word for find. The result was a series of massive anti-Carolinian riots that local authorities gave unofficial permission to, and resulted in the deaths of over 90 missionaries and traders. It took 3 months, but by August 14th, 1905, 10 ships and over 4,700 Marines had steamed up the Nakdong River and arrived in Daegu. The city was shelled for 48 consecutive hours, destroying over half of the city. Then, on August 18th, the Marines landed and slaughtered the local garrison, as well as anyone who resisted. Seoul was infuriated, but the prospect of a wider intervention stayed their hand for the time being.

Cokie Marines pose atop a destroyed fort outside of Daegu (1905)

The results of the Subjugation of Daegu were widespread. On the Carolinian side, it convinced Chancellor Gamble and the House of Citizens to fund the construction of the Pacific and Asiatic Squadrons of the Carolinian Navy, complete with a constant retainer of Marines. The funding wasn't the issue, but finding somewhere to dock the new ships and troops would be. To this end, Chancellor Gamble both negotiated with Philadelphia and Nippon, and decided to kick the Australians around a bit. When it came to Custer and Splendidfaith, Gamble worked out a deal where, for an annual multi-million dollar retainer fee, the Cokies could station their ships and soldiers freely in Nipponese and Yankee bases and ports all around the Pacific. However, Gamble also took the opportunity to engage in a little bullying. Secretly resenting his position as a Yankee puppet, Gamble would take any opportunity he could to harass and demean weaker powers in the Fascist sphere to make himself and Carolina feel stronger. To this end, he demanded that the Australians allow the Carolinian Navy free use of all Australian ports, and allow the stationing of Cokie troops in any port they chose. After using some heavy handed coercion, including a memorable incident where the Vulture-class battleship CNS Old Hickory steamed into Melbourne without permission, the Australians were forced to concede. This thrilled the Carolinian public to no end, who were happy to be pushing around a fascist state rather than being pushed around by one. By 1907, both squadrons were deployed or in the process of being deployed, crewed by an expanded number of sailors and marines. It wasn't a moment too soon either.