1995 - "Rails Through London" by John Mitten

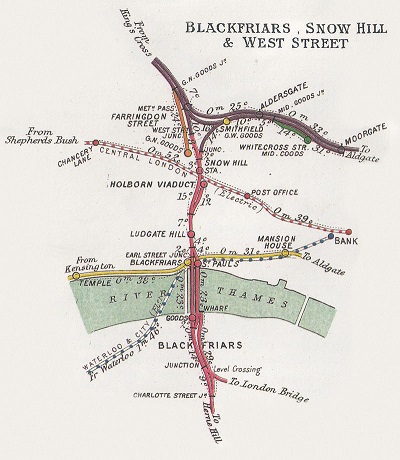

Historical rail around Blackfriars

The double track stretch of railway, usually called the "City Widened Lines", harks back to the Metropolitan Railway in 1863, and their requirement to quadruple track their own system (which would later form the London Underground Circle Line). The result would later see gradual separation between what would become the Underground tracks and the British Rail tracks, and then the introduction of goods depots in the area to serve the Great Western, Great Northern and Midland railways. Passenger operators ventured in via St Pancras and Kings Cross, allowing trains to terminate at Moorgate on the edge of the City of London. The link further south, towards Elephant & Castle or London Bridge did not prosper though due to the nearby London Underground alternatives; the route became a staple ingredient in cross-city freight services however (*1).

The cross-city link between Holborn Viaduct and Farringdon was later terminated, mostly due to the installation of an international rail terminus at Holborn Viaduct for trains to/from Europe. Originally deemed to be a temporary location, it lasted over 20 years and the station was far from ideal for that purpose. With the Beck Line the only rail access to the station, London Underground worked with British Rail on a new concept; a cross-city heavy rail link (*2). The joint proposal heavily references the Hamburg S-Bahn and Parisian RER system; both heavy rail cross-city routes, which were well used by passengers and commuters. The price of creating the London version was cheap compared to the route it would provide; the only significant expenditures would be the electrification of the Midland Main Line as far as Dunstable, the reconfiguration of the tracks just north of London Blackfriars to allow the new route to dive under the high speed tracks from Europe heading in to Holborn Viaduct, and the rolling stock itself. Freight trains would be diverted to run via the West London Line, via Kensington Olympia (*3).

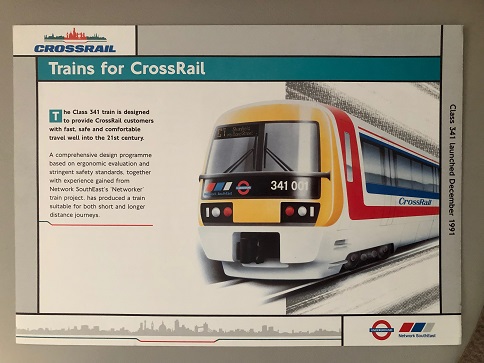

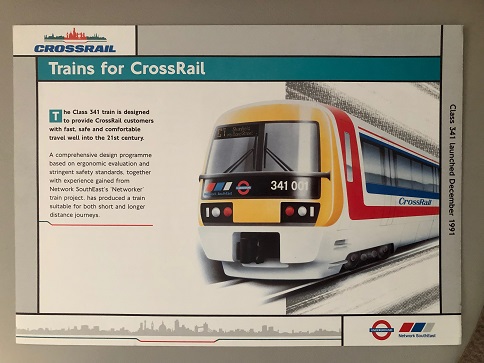

The under development Crossrail train - the 1991 date on the side actually refers to the project launch date, confusingly for readers. Note the dual Network South East and London Transport branding.

The new rolling stock would need to be dual voltage capable; neither British Rail nor London Transport had any intention of paying to convert the third rail system south of the river in to an overhead system. The tunnel itself, damp in places with the inherent safety risks of a highly powered rail along the ground, was converted to overhead power, with the changeover to the third rail system now occurring at Blackfriars station (which was dual equipped with both systems). Initial artistic mockups were quickly available, and used for advertising in the London Underground system early on, back in the days when the name for the new link looked to be "Crossrail". The design elements of both London Transport and Network South East are abundantly clear; the smaller wheels look similar to London Underground trains, although didn't make it through to production versions. The body, equally resigned would feature 2 sets of wider-than-normal doors for the expected heavier usage through central London, with seating only 2x2 transverse seating (*4), to allow space for standing passengers along the coaches.

Equally, the management structure changed. The project had been for years a joint NSE-LT one, but with the project approved by Government, choices had to be made for where it would sit within the London transport structures. This is where British Rail's new structure, even if somewhat foisted upon it, came up trumps. The route would be marketed as part of London Transport, and ticketed as such, branded as "London Overground", with London Transport accepting the revenue risk for the route. Any Thameslink-only stations would be managed and maintained by London Transport; shared stations (such as London Bridge) would continue to be British Rail/Network South East managed. Train/rail operation of the route would be done under contract to British Rail's "Abellio" unit (*5), for contract operations - legally speaking, the route would continue to form part of the British Rail network as Thameslink services would interweave with other NSE services, particularly around London Bridge. This was much to the chagrin of Network South East who stood to lose out financially from the deal. Operations would, a few years later, be transferred as a unique exception to Network South East due to their operation of all other routes in the area. Such a move simplified the management structure, as well as HR affairs (having a larger shared pool of drivers to utilise).

The new line, by 1993 branded as "Thameslink" instead, opened in 1994 (*6). The first routes saw an 8 trains per hour service (4 trains on each of the pair of branches to the north and south). To the north, the route ran as far as Luton using the Midland suburban lines, where it then diverged from the Midland Main Line and terminated at Dunstable. The other branch would take over the suburban lines of the East Coast Route as far as Welwyn Garden City - it could go no further north anyway, due to the restricted capacity Welwyn Viaduct which was only dual track (*7). A separate, but linked, project in the area would see Thameslink also operate the new "Hertford - Moorgate" service (*8), which would likewise utilise it's own tracks and be operated under the same Thameslink structure.

East Croydon station in quieter years.

To the south, the mess of routes, all diverging using flat junctions was made for difficulty in fitting a new service pattern through. For simplicity more than any other reason (although being well utilised was certainly a factor in the decision), the first branch was chosen to be the Greenwich & North Kent Line, with the Brighton Main Line as far as West Croydon in an effort to divert local passengers away from the busy East Croydon station (*9).

Passenger traffic grew rapidly; numbers more than quadrupled within the first year of operation as people enjoyed far faster cross-London services, with passengers numbers then continuing to grow at a lower rate (*10). The huge success of the new network encouraged British Rail and London Transport to work on improving the route. Extension of the northern branch at Dunstable along the mothballed former tracks to Leighton Buzzard were a quick win (*11), helping to divert some traffic away from the saturated West Coast Route. Contributions from the British Airports Authority to extend again the short distance to Britannia Airport would give another rail link to the airport (*12), and allow public transport access via another axis of towns, whilst a smaller contribution from Hertfordshire County Council was for the same thing due to the high levels of congestion around Leighton Buzzard on roads to access the airport. The airport, which had been operating for over a decade now, was in full swing of the "low cost carrier" boom, and was planning for a new "international terminal" to handle all international flights. The existing terminal, now too small for requirements, would be used for all domestic and Irish flights where customs, immigration and security check requirements were far lower (*13).

2005 would see the beginning of the "Thameslink Programme" (*14). This would see improvements on the North Kent Line, with better separation in to terminal platforms at Dartford, as well as a new branch stub to serve Thamesmead. On the Croydon branch, services would be extended from West Croydon to new terminating platforms at Sutton (*15). Both branches would call at a new station at Bermondsey, where the former Spa Road station used to be sited (*16), to improve access to this area of London. Improved service frequencies would occur on both branches to 6 trains per hour (a train every 5 minutes through the core section). Through the middle core section, new flyovers would be required to the north and south of London Bridge station to separate the route from other Network South East services as much as possible, whilst reconstructed platforms at Farringdon would lend some extra width to the platforms. However, most of the changes would lie around the Kings Cross & St Pancras area. The former Kings Cross York Road platform(s) (*17), allowing access from the Thameslink route to the East Coast Route would be closed, with a new set of platforms to be built below the northern area of St Pancras station to service both stations (*18). The tracks would then continue north, to serve the new Boudica station (*19), where it would then separate in to two sets of tracks to towards the Midland Line or the East Coast Route. The works concluded 10 years later in 2015, but an extension to the project agreed in 2009 would see Finsbury Park station reorganised to allow better cross-platform interchange between the two Thameslink branches, allowing quicker access to Moorgate and the City of London from Welwyn. Finally, new Class 378 rolling stock, operating would operate the route, featuring similar 2x2 transverse seating as well as luggage racks for airport-bound passengers, but with inter-carriage connections to allow passengers to spread along the train more easily.

New Class 378 rolling stock, with London Overground livery.

----------------------------

(*1) This first paragraph is all roughly OTL.

(*2) This TL version of Eurostar is obviously hindered by the less connected terminus at Holborn Viaduct; the Beck Line is directly connected. The Central Line is underneath, but it's technically difficult to create new platforms on a route which is in heavy use without taking it out of service which is somewhat difficult for such a busy line. Farringdon station is perhaps 400m walk away with the services there. So, obviously, Holborn Viaduct adds an extra reason for this route.

(*3) Roughly as per OTL; cross-London freight either running via the West London Line, or electric freight (especially from the Channel Tunnel) using the London Orbital Line Ashford-Tonbridge-Redhill-Guildford-Reading-Oxford-Bletchley-Bedford-Cambridge-Bury-Ipswich as discussed in previous chapters.

(*4) Transverse seating is more comfortable for longer distance travellers, but obviously need some standing room for when it goes through central London.

(*5) Abellio was one of the British Rail subsidiary units, when we covered the BR reorganisation a few chapters ago.

(*6) Surprise, surprise, it's ended up with the OTL name of Thameslink. Funnily enough, means I can use pictures from OTL....

(*7) Welwyn Viaduct is a capacity bottleneck in OTL too, and is why the suburban service terminates at Welwyn Garden City.

(*8) The Northern City Line is an offshoot of the Thameslink network, with a Hertford North to Moorgate service.

(*9) Chose North Kent Line (Greenwich-Woolwich-Dartford) as a) it's on the north side of the junctions, so easily accessible using separated lines, serves busy areas, connects with Beck Line at Greenwich, and can also access as far as Dartford with minimal further works. The Brighton Main Line to West Croydon is equally busy, and also will ease London Bridge somewhat. What the role for Cannon Street is longer term is an open question.

(*10) As per OTL.

(*11) The line Luton-Dunstable was still in use for freight until the late 1980s; here it's continued a little longer, and now happily accommodating Thameslink trains.

(*12) The line beyond Dunstable is mothballed, but easily reactivated, and a short stretch from Leighton Buzzard to the airport to allow more public access to the airport without car.

(*13) Britannia Airport is large and expanding rapidly.

(*14) Imaginative name I know....

(*15) Using space available next to the station.

(*16) As there is no tube line station at Bermondsey in this TL, and much of the space/works required are still there.

(*17) These platforms were taken out of use in the 1970s OTL, but here are still present and being used for Thameslink until now.

(*18) New Kings Cross / St Pancras Thameslink station built roughly where the new one under St Pancras International is in OTL.

(*19) Boudica Station making an appearance here...