You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Anglo-Saxon Social Model

- Thread starter Rattigan

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 190 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Alexander Ministry (2024-2025) Miliband Ministry (2025-2026) Western Canada Independence Referendum, 2024 Western Australia Independence Referendum, 2027 Second Yugoslav War (2009-2029) Stewart Ministry (2026-2031) Commonwealth Election of 2031 World Map, 31 December 2030So. Is the Commonwealth about to have an outbreak of commonsense ?

I'm afraid so.

How would the political landscape change after labour returned to goverment in 1981?

Their manifesto in 1981 promised reform of Commonwealth fiscal structures and end to the forced austerity of the Thatcher years.

Returning to a previous topic you said that in TTL , Beeching (or the ttl equivalent) called for retention of the entire rail network and wide scale electrification . Considering that, by 1981, how large would the electrified railway network be and another question (as a rail enthusiast) - Was steam traction retired by 1981 or it is still fine and well?

PS: Refering just to Britain, not the Commonwealth in general

PS: Refering just to Britain, not the Commonwealth in general

Last edited:

Space Exploration, 1953 - 1981

Returning to a previous topic you said that in TTL , Beeching (or the ttl equivalent) called for retention of the entire rail network and wide scale electrification . Considering that, by 1981, how large would the electrified railway network be and another question (as a rail enthusiast) - Was steam traction retired by 1981 or it is still fine and well?

PS: Refering just to Britain, not the Commonwealth in general

Steam traction is still around but only on heritage lines, I'm afraid. You won't find it on the main railways anymore. The electrified network is very large and accounts for just over 50% of total passenger kilometres. The first full trunk line was opened in 1970, connecting London-Birmingham-Manchester-Glasgow-Edinburgh and was expanded to connect all the major cities in England, Wales and Scotland (as well as one linking Dublin and Belfast) over the course of the 70s to early 80s. The backbone of the rail system, however, remains commuter rails: the most popular railway is the London Orbital Railway (TTL's M25 equivalent), which was constructed between 1966 and 1976.

* * *

Also, I've just remembered that someone a while ago asked me how space exploration is going so here's a quick and dirty list of the major 'firsts' up to the end of 1981.

4 March 1953 - first artificial satellite - Commonwealth/Megaroc 6

3 April 1953 - first animal (a dog named 'Lucky') in orbit - Commonwealth/Megaroc 7

19 April 1956 - failure of the first Commonwealth manned mission - Commonwealth/Sol 1

7 August 1956 - first photograph of Earth from orbit - USA/Explorer 6

13 October 1956 - first impact on the moon - Soviet Union/Luna 2

19 March 1957 - first animals to return alive from orbit - Soviet Union/Luna 7

14 February 1958 - first flyby of Venus - Commonwealth/Megaroc 16

15 July 1959 - first solar probe - Soviet Union/Perun 5

14 November 1959 - first flyby of Mars - Commonwealth/Megaroc 19

12 December 1959 - first human spaceflight (Alexei Ledowsky) - Soviet Union/Vostok 1

17 January 1960 - first American in space (John L. Whitehead, Jr.) - USA/Mercury 3

26 November 1961 - first impact on the far side of the moon - USA/Ranger 4

14 October 1963 - first close-up photos of Mars - Commonwealth/Halley 3

1 March 1964 - first spacewalk (Yuri Gagarin) - Soviet Union/Voskhod 1

5 November 1964 - first unmanned orbit of the moon - Soviet Union/Luna 11

18 May 1965 - first Commonwealth citizen in space (Lee Jones) - Commonwealth/Sol 3

21 December 1965 - first piloted orbit of the moon - USA/Apollo 8

20 April 1967 - first man on the moon (Gus Grissom) - USA/Apollo 11

19 February 1971 - launch of the first space station - Commonwealth/Salute 1

2 December 1971 - first Soviet man on the moon (Gherman Titov) - Soviet Union/Zond 8

4 September 1972 - first Commonwealth man on the moon (Philip K. Chapman) - Commonwealth/Cook 6

26 September 1972 - first soft landing on Mars - USA/Voyager 8

8 June 1974 to 20 February 1975 - first manned orbit of Venus - USA/Traveler 7

16 August to 13 September 1974 - first lunar base, first plants grown on the moon, first mission to spend more than a week on the moon - Commonwealth/Cook 12

11 July 1975 - first soil samples recovered from Mars - Commonwealth/Newton 3

12 April 1979 - first use of reusable spacecraft - Commonwealth/Space Shuttle

5 November 1980 - launch of first extended orbital exploration of Mars - USA/Traveler 13

11 July 1981 - launch of the first Soviet space station - Soviet Union/World

Recovered as in brought back to Earth?11 July 1975 - first soil samples recovered from Mars - Commonwealth/Newton 3

Basically what went wrong when we went comprehensive was we tried to do it on the cheap and went for a baseline secondary modern model with grammar and technical streams. We could have had a much more skilled and better educated workforce today if we had either stuck to the OTL Butler tripartite strands and put more funding into developing the technical schools or went comprehensive on the technical school model with grammar streams for the arts types and a highly vocational and life skills stream for the unacademic. Either of which of course would have come more expensive and Treasury is great at being penny wise and pound foolish!You also said ttl about the reforms Barbara Castle started in education. In 1981, how would the structure and curriculum of british schools look like?

You also said ttl about the reforms Barbara Castle started in education. In 1981, how would the structure and curriculum of british schools look like?

Basically what went wrong when we went comprehensive was we tried to do it on the cheap and went for a baseline secondary modern model with grammar and technical streams. We could have had a much more skilled and better educated workforce today if we had either stuck to the OTL Butler tripartite strands and put more funding into developing the technical schools or went comprehensive on the technical school model with grammar streams for the arts types and a highly vocational and life skills stream for the unacademic. Either of which of course would have come more expensive and Treasury is great at being penny wise and pound foolish!

So the basic structure of the education reform is the same country-wide (daycare/creche 1-7; compulsory schooling 7-16; optional further two years (16-18); and then undergraduate (18-21) or polytechnic qualifications (18-22)). What the nature of the schooling looks like from 7-16 is pretty much how @ShortsBelfast describes it: comprehensive on the technical school model with vocational and arts streams for the relevant students. The nature of the UK's economy TTL means that even vocational studies can be quite technical and are by no means reserved for only the 'dumb kids.' Children also move between the vocational, arts and comprehensive streams fairly often and everyone tends to be housed in the same school buildings to the extent possible. Up to the age of 16, schooling is managed on three levels: the physical schools themselves are administered by local councils; the syllabi the schools teach are managed by the relevant devolved assemblies (this was a kind of compensation for abolishing the separate Irish and Scottish education systems); and the leaving certificate at 16 is administered by the Westminster government. In practice, this means that the education system up to the age of 16 is run in collaboration between councils, assemblies, Westminster and the teaching unions (which run what is effectively a closed shop).

The years 16-18 are run slightly differently. Although students in these years are often taught in the same buildings as the schools they attended in the years previously, schools rarely have control over their education. Instead, these two years are regarded as preparation for university or polytechnic and so the syllabi and final examinations are largely run by an education board made up to representatives of polytechnics, universities and the ubiquitous teaching unions. The main point of these two years is to prepare the students for tertiary education, so courses are run closer to university lecture courses than an ordinary school class. Teachers at this level are often hired directly by the universities/polytechnics and paid by local authorities.

Tertiary education is largely run on a national level. TTL the split between polytechnics and universities has largely evaporated and will be abolished at some point in the 1980s, with all university undergraduate degrees lasting four years. All by now offer a full suite of science and arts subjects. In the first year of university, much like in the American system, students are encouraged to take a wide range of classes before specialising in their final three years. University/polytechnic enrolment exploded in the 1940s and '50s (thanks to a British equivalent of OTL's US GI Bill) and has stabilised by the '80s at about 50% of school-leavers. Although university students are all given a grant and do not have to take out loans (although many banks do offer cheap loans to students to supplement their grants), graduates do pay an additional 1% on their income tax rate up to the age of 50.

The other thing to say is that the education system in the Crown Dependencies is integrated into the main UK education system, with the legislatures of Jersey, Guernsey and the Isle of Mann slotting in at the level of the devolved assemblies. In 1949 the island of Herm was bought by the Department of Education and developed into the University of the Channel Islands (opened 1957) and is now a pretty prestigious institution, with both French and English classes and qualifications offered.

Recovered as in brought back to Earth?

Yes.

I'm quite interested in the daycare/creche as to how comprehensive it is are we talking free for everybody, or only those of poorer backgrounds. As I live in a country with pretty poor demographics I'm curious as to the demographic backgrounds of the UK in TL such as overall population ethnic makeup, fertility rates and how the welfare state has developed in these area's such as the free childcare but also other things such as subsidies for single mothers, flexitime etc and attitudes towards this thanks.

I'm quite interested in the daycare/creche as to how comprehensive it is are we talking free for everybody, or only those of poorer backgrounds. As I live in a country with pretty poor demographics I'm curious as to the demographic backgrounds of the UK in TL such as overall population ethnic makeup, fertility rates and how the welfare state has developed in these area's such as the free childcare but also other things such as subsidies for single mothers, flexitime etc and attitudes towards this thanks.

We're talking free to everybody with, by the 1980s, the social expectation being that children will be sent to them as soon as possible, although attendance isn't compulsory. There is also a nationwide minimum of one year maternity leave (some devolved assemblies, generally ones with cultures more focused on 'family values,' offering more generous lengths), ensuring that a working woman can take one year paid leave after her child's birth and then return to work with after that with her childcare taken care of for free. What is actually taught in these creches depends on the relevant devolved administration, with some regions treating them as basically supervised playgrounds for children (e.g. Greater London) and others taking a more structured approach (e.g. the Midlands).

Since the UK began to expand its welfare state in the late 19th century, the government has also been obsessed with ensuring full employment in order to ensure that there are enough tax revenues to subsidise the expansive welfare state. Under Chamberlain, Dilke and Lloyd George, this meant full male employment but it expanded to include women in the postwar period. This, combined with the aim of welfare being the decommodification of the citizen and the presence of figures like Barbara Castle and Alice Bacon at the top of government, has created a governmental system in the UK almost uniquely generous towards women, including single mothers. While it would be wrong to say that there isn't any stigma against being in a 'broken home' (particularly in Ireland), these kinds of views are increasingly found only amongst older generational cohorts and rapidly dying out amongst the young. The institution of no-fault divorces in the 1960s has increased the opportunity for women (and men) to leave loveless marriages and numerous shelters exist to help women fleeing domestic abuse. Abortion is legal and law mandates the maintenance of at least one NHS-run abortion clinic available in each devolved region. Flexitime and similar ideas aren't really much of thing, to be honest, because of the aforementioned childcare laws don't make it as much of an issue for working parents. But, that being said, the more powerful unions (who have representation on company boards) mean that such things are likely to be introduced on a company-by-company basis should there be a desire for them amongst workforce.

In terms of birthrates, I don't anticipate a vast difference between OTL and TTL. I think it will be slightly lower because the country is richer (which tends to lower birthrates at the margins), immigration patterns are different (I'll explain below) and the government has rolled out expansive family planning programmes to make contraception available but nothing remarkably so.

On immigration, on a macro level things would look pretty similar but there are important differences at the margins. About 92% of the population are UK-born, 6% born in other Commonwealth member states and the remaining 2% born elsewhere in the world. This translates as, in 1980, an ethnic composition of around 92% white (the UK operates its own kind of one-drop rule whereby you're counted as white for demographic purposes if one of your parents was counted as white), 3% south Asian, 2% east Asian, 2% Afro-Caribbean (which includes Puerto Ricans as 'Caribbeans') and 1% Arabs, non-Puerto Rican Latinx and general other. In the '40s there was a big drive to encourage immigrants from Puerto Rico, the West Indies and Pakistan but many of those went back in the 50s and 60s because of an economic boom in those countries. Nowadays much of the immigration is from poorer Commonwealth countries like Sarawak, Papua New Guinea and the Pacific Islands. This initially caused racial tension but this has been partially defused through the institution of the Race Relations Board in the 1960s, general generational change and the increased visibility of non-white fellow Commonwealth citizens through things like the CBC. There is also notable emigration to other Commonwealth countries, with the West Indies, East Africa, Pakistan, Canada and Australia being popular destinations.

That being said, there is still discrimination against non-Commonwealth foreigners and particular venom is reserved for those from the German successor states, who had the misfortune of being seen as both a vanquished enemy and poor freeloaders on the UK's success. In 1962, immigration from all the German successor states apart from Hanover was effectively banned. Other than that, it can be tricky to get a UK visa if you're from a non-Commonwealth country but the authorities have lowered the requirements for a freelance visa in recent years. It should also be noted that the full suite of social security services remain available to the new immigrant from the day of their arrival. This does kind of create the conditions for a potential demographic crisis in upcoming decades but not quite yet and, so far, policy-makers think it can be solved by encouraging Commonwealth immigration.

How is there still bad blood against Germans? First they lost the war, then their country is broken up into small states, and now they can't even live in the UK? It must've suck to be a German ITTL.

Last edited:

I think my comments earlier about how the Puerto Rican independence crisis seemed so familiar turned out to be pretty damn accurate in hindsight. Seriously, the chaos in Puerto Rico's government was described in terms I swear I could've read on an OTL British news website. The incoherent exit deal that tried to have it both ways and went down to an ignominious defeat. The antagonistic relationship between San Juan and London. The alienation of moderates in order to pursue the dreams of the hardline pro-exit wing of the governing party. At least it seems to have a happy ending here.

I think my comments earlier about how the Puerto Rican independence crisis seemed so familiar turned out to be pretty damn accurate in hindsight. Seriously, the chaos in Puerto Rico's government was described in terms I swear I could've read on an OTL British news website. The incoherent exit deal that tried to have it both ways and went down to an ignominious defeat. The antagonistic relationship between San Juan and London. The alienation of moderates in order to pursue the dreams of the hardline pro-exit wing of the governing party. At least it seems to have a happy ending here.

I wonder if Puerto Rico is meant to represent Greece or the UK here.

The Hogg-Manley Reforms, 1981-1986

Adults in the Room: The Hogg-Manley Reforms and the Rescue of the Commonwealth

The eponymous Hogg and Manley

While Rodgers busied himself with domestic reform, he largely entrusted Commonwealth reform to his foreign policy team. Roy Jenkins did not move from Shadow Chancellor to the main job (that went to Dennis Healy, who had recovered from his slip of the tongue in 1976) but instead took up the job at the Foreign Office. Rodgers appointed Peter Shore, who had finished an eight-year stint as President of the Commonwealth Council in 1980 to return as a list MP in 1981, to the position of Commonwealth Secretary. Shore had been at loggerheads with the Big Four during the course of Thatcher’s premiership and by 1981 was a strong believer in the need for Commonwealth reform. Jenkins was more ambivalent on the issue but recognised the need for change after the failures of the previous decade.

The events of October 1981, both the general election in Puerto Rico and Durbin’s announcement of a defence of the pound, had given the Commonwealth breathing room. The economy returned to growth in the next two quarters and political tensions calmed. This in turn bought time for Shore and his reformist allies to prepare a massive reform package that was unveiled at a roundtable Commonwealth conference in April 1982. The centre point of the package was a series of widened powers for the Bank of England, the most notable of which was the proposal to give it the power to issue government bonds in decimalised sterling on behalf of all of the Commonwealth member states jointly. This was a major concession by the strong economies in the Sterling Zone and was important in further calming the structural problems facing heavily indebted countries. Under the new rules, governments of member states would be able to petition the Bank of England to make an issuance of these Commonwealth bonds and remit the funds to them. The bonds were then secured against the solvency of the Commonwealth as a whole, ensuring that interest rates would remain low (at least in theory). The Bank of England would be required to make the bond issuance provided that doing so would not cause serious damage to the integrity of the Commonwealth as a whole. In practice, this allowed smaller countries to borrow money on the international markets at significantly lower rates than previously available to them.

Tied to these technical monetary policies, Hailsham and Manley worked with their allies to push through a swath of Commonwealth legislation that moved well past the precedents which had been largely kept to since the Assembly had been established in the 1950s. Both agreed with Shore and the other big Four representatives that radical actions were required to reduce the overall Commonwealth debt to a sustainable level. The figure chosen was a write-off of £1,000,000,000. This was to be financed by a one-time wealth-tax of between 15 and 30% (depending on national wealth) levied on the non-crisis countries. Crisis countries, notably Puerto Rico, were not required to pay. In addition, the Commonwealth Assembly passed a regular flat tax of 10% on private wealth.

These Hogg-Manley Reforms, as they came to be known (Hailsham’s family name of ‘Hogg’ has traditionally been used in connection with them, for unclear reasons), were remarkable: combining radicalism and redistribution with an enormous expansion of the scope of the Commonwealth. It was politically contentious too and, realistically, was only allowed to pass because of the desperation of the political leaders for a change of tack following the disastrous 1970s. Across the Commonwealth, the political results were uneven even as, economically, the bloc returned to rude health. In Rhodesia, the troubles of the 1970s had caused the fall of the decades-long premiership of Garfield Todd, replaced by, first, Abel Muzorwera’s Liberals and, then, Joshua Nkomo’s Labour. Labour’s consecutive wins in 1979 and 1983 cemented Nkomo’s domination of the political scene and the final triumph of the promise of majority rule (although Rhodesia would remain a country with notable economic and racial inequality for many years to come). In East Africa, the general Commonwealth economy gave a boost to the country’s agricultural and tourism sectors and Julius Nyere’s Socialist Party won a second term with a narrow victory in 1985.

But it was of course to Puerto Rico that everybody looked to see how things would bed in. Following the failure of his exit package, Berrios had slunk into retirement to be replaced by his former enemy Fernando Martin Garcia. Martin Garcia dropped Berrios’ commitment to leaving the Commonwealth and successfully reunited the New Porgressive and Green Parties into the Progressive Green Party. With the threat of leaving the bloc removed, the Conervative-Democratic grand coalition predictably fell out over domestic policy, with a minor dispute over the management of the national health insurance service being the final straw that provoked the Democrats to leave. Romero Barcelo lost the subsequent elections in December 1982 and Rafael Hernandex Colon became prime minister at the head of a Democratic-Progressive Green coalition. Many observers noted with surprise how little the Hogg-Manley reforms came up in the campaign.

Indeed, while there was some attempt to paint the subsequent elections in the Big Four as some kind of referendum on the Hogg-Manley Reforms, these were semi-successful at best. Of the elections that the Big Four did have in the next five years, only the Australian one in 1983 was really seen at the time as dominated by an argument over the incumbent government’s role in passing the Reforms (in this case Gough Whitlam’s Labour Party, who were successful in their re-election bid). By the time that Pakistan and Canada went to the polls in 1985 and 1986, respectively, it was in fact remarkable how little the Hogg-Manley Reforms came up. In Pakistan, Bhutto’s government was eventually brought down over it’s perceived failure to get to grips with continued trades union issues. In Canada, Jean-Luc Pepin’s Liberals managed to retain their coalition majority off the back of a campaign dominated by the question of the potential secession of the western provinces.

On the other hand, it is undeniable that the Hoog-Manley Reforms did generate a wave of critique that came to be known as Angloscepticism. However, what practical results this could achieve appeared limited, at least in the short term. Most notably, Angloscepticism initially thrived as an oppositionist platform, finding a home, where it did at all, in whichever party was out of power at the time. So, in Puerto Rico, it came to be associated with the further left reaches of the New Progressive Party. In 1987, two MPs would split off to form the Puerto Rican Independence Party (“PRIP”), which would find a certain kind of audience, if only marginal electoral success, in the following years. Similarly, in Newfoundland it was often associated with the more statist Liberal Party. But on the other hand, in other countries it became a right wing movement, associated in Pakistan with the Liberals, in Canada with Progressive Conservatives and in Australia with the Liberals. (In this context the uneven naming conventions of parties in Commonwealth member states can be extremely confusing.) As David Marquand asked, rather contemptuously, of the movement: “what goals do a Puerto Rican Marxist, a Pakistani factory owner and a Cornish smallholder truly have in common?”

What indeed?

The eponymous Hogg and Manley

While Rodgers busied himself with domestic reform, he largely entrusted Commonwealth reform to his foreign policy team. Roy Jenkins did not move from Shadow Chancellor to the main job (that went to Dennis Healy, who had recovered from his slip of the tongue in 1976) but instead took up the job at the Foreign Office. Rodgers appointed Peter Shore, who had finished an eight-year stint as President of the Commonwealth Council in 1980 to return as a list MP in 1981, to the position of Commonwealth Secretary. Shore had been at loggerheads with the Big Four during the course of Thatcher’s premiership and by 1981 was a strong believer in the need for Commonwealth reform. Jenkins was more ambivalent on the issue but recognised the need for change after the failures of the previous decade.

The events of October 1981, both the general election in Puerto Rico and Durbin’s announcement of a defence of the pound, had given the Commonwealth breathing room. The economy returned to growth in the next two quarters and political tensions calmed. This in turn bought time for Shore and his reformist allies to prepare a massive reform package that was unveiled at a roundtable Commonwealth conference in April 1982. The centre point of the package was a series of widened powers for the Bank of England, the most notable of which was the proposal to give it the power to issue government bonds in decimalised sterling on behalf of all of the Commonwealth member states jointly. This was a major concession by the strong economies in the Sterling Zone and was important in further calming the structural problems facing heavily indebted countries. Under the new rules, governments of member states would be able to petition the Bank of England to make an issuance of these Commonwealth bonds and remit the funds to them. The bonds were then secured against the solvency of the Commonwealth as a whole, ensuring that interest rates would remain low (at least in theory). The Bank of England would be required to make the bond issuance provided that doing so would not cause serious damage to the integrity of the Commonwealth as a whole. In practice, this allowed smaller countries to borrow money on the international markets at significantly lower rates than previously available to them.

Tied to these technical monetary policies, Hailsham and Manley worked with their allies to push through a swath of Commonwealth legislation that moved well past the precedents which had been largely kept to since the Assembly had been established in the 1950s. Both agreed with Shore and the other big Four representatives that radical actions were required to reduce the overall Commonwealth debt to a sustainable level. The figure chosen was a write-off of £1,000,000,000. This was to be financed by a one-time wealth-tax of between 15 and 30% (depending on national wealth) levied on the non-crisis countries. Crisis countries, notably Puerto Rico, were not required to pay. In addition, the Commonwealth Assembly passed a regular flat tax of 10% on private wealth.

These Hogg-Manley Reforms, as they came to be known (Hailsham’s family name of ‘Hogg’ has traditionally been used in connection with them, for unclear reasons), were remarkable: combining radicalism and redistribution with an enormous expansion of the scope of the Commonwealth. It was politically contentious too and, realistically, was only allowed to pass because of the desperation of the political leaders for a change of tack following the disastrous 1970s. Across the Commonwealth, the political results were uneven even as, economically, the bloc returned to rude health. In Rhodesia, the troubles of the 1970s had caused the fall of the decades-long premiership of Garfield Todd, replaced by, first, Abel Muzorwera’s Liberals and, then, Joshua Nkomo’s Labour. Labour’s consecutive wins in 1979 and 1983 cemented Nkomo’s domination of the political scene and the final triumph of the promise of majority rule (although Rhodesia would remain a country with notable economic and racial inequality for many years to come). In East Africa, the general Commonwealth economy gave a boost to the country’s agricultural and tourism sectors and Julius Nyere’s Socialist Party won a second term with a narrow victory in 1985.

But it was of course to Puerto Rico that everybody looked to see how things would bed in. Following the failure of his exit package, Berrios had slunk into retirement to be replaced by his former enemy Fernando Martin Garcia. Martin Garcia dropped Berrios’ commitment to leaving the Commonwealth and successfully reunited the New Porgressive and Green Parties into the Progressive Green Party. With the threat of leaving the bloc removed, the Conervative-Democratic grand coalition predictably fell out over domestic policy, with a minor dispute over the management of the national health insurance service being the final straw that provoked the Democrats to leave. Romero Barcelo lost the subsequent elections in December 1982 and Rafael Hernandex Colon became prime minister at the head of a Democratic-Progressive Green coalition. Many observers noted with surprise how little the Hogg-Manley reforms came up in the campaign.

Indeed, while there was some attempt to paint the subsequent elections in the Big Four as some kind of referendum on the Hogg-Manley Reforms, these were semi-successful at best. Of the elections that the Big Four did have in the next five years, only the Australian one in 1983 was really seen at the time as dominated by an argument over the incumbent government’s role in passing the Reforms (in this case Gough Whitlam’s Labour Party, who were successful in their re-election bid). By the time that Pakistan and Canada went to the polls in 1985 and 1986, respectively, it was in fact remarkable how little the Hogg-Manley Reforms came up. In Pakistan, Bhutto’s government was eventually brought down over it’s perceived failure to get to grips with continued trades union issues. In Canada, Jean-Luc Pepin’s Liberals managed to retain their coalition majority off the back of a campaign dominated by the question of the potential secession of the western provinces.

On the other hand, it is undeniable that the Hoog-Manley Reforms did generate a wave of critique that came to be known as Angloscepticism. However, what practical results this could achieve appeared limited, at least in the short term. Most notably, Angloscepticism initially thrived as an oppositionist platform, finding a home, where it did at all, in whichever party was out of power at the time. So, in Puerto Rico, it came to be associated with the further left reaches of the New Progressive Party. In 1987, two MPs would split off to form the Puerto Rican Independence Party (“PRIP”), which would find a certain kind of audience, if only marginal electoral success, in the following years. Similarly, in Newfoundland it was often associated with the more statist Liberal Party. But on the other hand, in other countries it became a right wing movement, associated in Pakistan with the Liberals, in Canada with Progressive Conservatives and in Australia with the Liberals. (In this context the uneven naming conventions of parties in Commonwealth member states can be extremely confusing.) As David Marquand asked, rather contemptuously, of the movement: “what goals do a Puerto Rican Marxist, a Pakistani factory owner and a Cornish smallholder truly have in common?”

What indeed?

Last edited:

Hi all.

Quick bit of housekeeping but I just wanted to let you know that I've added a bit to the update I made a while ago covering Barbara Castle's third term (1971-76). As you might have noticed, I'm often going back to make small little edits because I'm one of those guys who thinks work is never finished, only abandoned. But those are just stylistic/grammar changes and this is a substantive addition so for the sake of completeness I've pasted the text I added, below. I've also added a link to the changed update too incase any of you want to boost my fragile self-esteem by throwing a few more likes its way.

"In 1973 the government rolled out a programme of connecting every Westminster to the NPL Network (now renamed the 'inter-departmental communication network' or 'internet'). The programme would subsequently be rolled out to the devolved assemblies in 1976 and local government institutions in 1979. "

https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...xon-social-model.458146/page-32#post-19192419

Quick bit of housekeeping but I just wanted to let you know that I've added a bit to the update I made a while ago covering Barbara Castle's third term (1971-76). As you might have noticed, I'm often going back to make small little edits because I'm one of those guys who thinks work is never finished, only abandoned. But those are just stylistic/grammar changes and this is a substantive addition so for the sake of completeness I've pasted the text I added, below. I've also added a link to the changed update too incase any of you want to boost my fragile self-esteem by throwing a few more likes its way.

"In 1973 the government rolled out a programme of connecting every Westminster to the NPL Network (now renamed the 'inter-departmental communication network' or 'internet'). The programme would subsequently be rolled out to the devolved assemblies in 1976 and local government institutions in 1979. "

https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...xon-social-model.458146/page-32#post-19192419

I just hope this has a better reputation than OTL government IT projects.

That wouldn't be hard, in fairness.

First Rodgers Ministry (1981-1986)

The Banality of Revolution: Bill Rodgers in Power

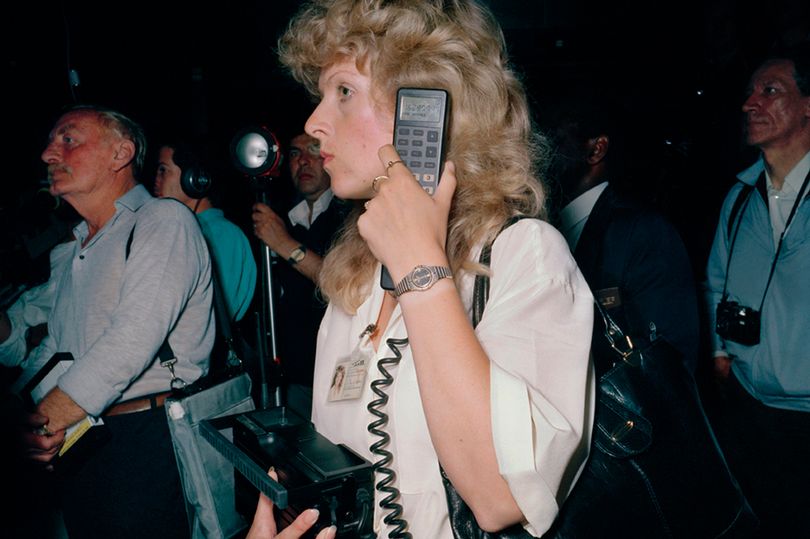

Living on the Edge: The return of economic prosperity in the 1980s saw an explosion of new fashions and technology

Labour had returned to power in 1981 mainly on the back of popular discontent with Liberal rule but its programme for government had been vague. When he got into office, Rodgers delegated much of the responsibility for what became the Hogg-Manley Reforms to Roy Jenkins and Peter Shore while he attempted to get to grips with the domestic problems that the Thatcher government had left behind it. Despite the attention of historians being focused on her government’s handling of Commonwealth and environmental affairs, at the time the foremost legacy of Thatcher’s premiership in Britain was thought to be her and Keith Joseph’s savage cuts to the welfare state. Labour had opposed the Liberals’ cuts to social security but it was not clear, now they were in power once more, whether Labour intended to simply reverse them or do something else. In general terms, there were three main schools of thought within the party.

The first school was dominated by what was generally considered to be the left of the party (although in this context they were kind of the most conservative) but had adherents from across most of the party’s political spectrum. In general terms, these people were in favour of simply returning to the model which had obtained in the UK since 1945. In practice, this would involve simply reversing Joseph’s budgets, with a few additions or subtractions around the edges (according to the flavour of the individual MP). A prominent exponent of this tendency was Michael Foot but his appointment as Education Secretary after the 1981 election indicated that he would be less influential in Rodgers’ final economic decision-making.

The second school was much smaller, made up of a small coterie of MPs on the right wing of the party. They had mixed feelings about many of the Thatcher-era cuts, viewing the 45-76 welfare state as in need of being trimmed. In practice, many of them viewed welfare as of secondary importance to other government programmes such advancing equality of opportunity and the maintenance of markets. Roy Jenkins was associated with this grouping but was, in truth, never fully of it and its informal cabinet-level spokesman was David Owen. Owen’s appointment as Defence Secretary was, like the appointment of Foot to Education, regarded by many as a sign that his tendency was being sidelined.

The final school was arguably the smallest but may have been the most adventurous. This school saw the question of welfare reform not just as one of whether to reverse or retain the Thatcher-era cuts but as an opportunity to replace them with something else. This attracted figures from across the political spectrum, from the technocratic Tony Benn through to Shirley Williams on the left and John Smith closer to the right. In many respects they were less of a coherent wing than a kind of parliamentary think tank - with some favouring an American-style guaranteed jobs programme, others a universal basic income and others nursing even more adventurous ideas. But the force and energy of their ideas, alongside the heterodox voices advancing them inside the party, meant that they attained a level of influence outside of their mere numbers.

In this context, Rodgers’ managerial, conciliatory style proved immensely valuable not only in making sure that the parliamentary party remained united but also that the policy debates were carried out internally rather than in the pages of the press. An informal ‘welfare cabinet’ was put together to manage and coordinate welfare reforms, consisting of Rodgers himself, the Chancellor Denis Healy, Home Secretary Roy Hattersley, President of the Board of Trade Tony Benn and Welfare Minister Shirley Williams. With figures drawn from across the party’s political spectrum, it also demonstrated the government’s openness to new ideas.

Over the next five years, Rodgers’ government rolled out a series of policies that were a mixture of fudge and ambition. Most of the Thatcher-era cuts were rolled back, with between two-thirds and three-quarters being simply reinstated. (Estimates vary in this context due to the fact that certain benefits were reinstated with different methods of calculating them.) In particular, social security payments relating to disability and maternity assistance were brought back in 1981 and increased in 1983 and 1984 as the economy recovered.

In the winter of 1982/3 the government unveiled the first part of its most ambitious reform package: an unconditional income guaranteed to all families. A trial run began in the Irish province of Ulster in January 1983, with plans for a national roll-out in the 1984/85 financial year in the event of successful results there. Millions of pounds were budgeted to provide the 1,600,000 people in Ulster with a guaranteed income of £200 a month. The trial had three big questions that it needed to answer: firstly, would people work less (or at all) with a guaranteed income?; secondly, would the program be too expensive; and, finally, would it be politically feasible?

Contrary to many of the predictions of its opponents, researchers found that the reduction in working hours was small to negligible. What declines did occur were mostly attributed to people with young children. Other declines were thought to have been compensated by people performing other useful activities, such as a search for better jobs. One mother took a night course in psychology and got a job as a researcher at Queen’s University. Another took acting classes while her husband indulged his previously private passion for classical music composition. Amongst people in their teens and twenties there was an increase in part-time and further education, including re-training for new jobs. Although it still had its opponents in the cabinet (not least Healy, who was quietly reshuffled in February 1984 in favour of Smith), the government announced that the plan would be rolled out across the entire nation for the financial year 1984/85.

After 1982, the economy began to return to growth, averaging 4% per annum by the beginning of 1986. There remains a significant controversy about the reasons for this growth, with some people identifying the calming effects of the Hogg-Manley Reforms, while others give credit to the increased profits of the SWF following the successful diversifying of its portfolio and an oil-price spike in the early 1980s.

The final major development in Rodgers’ first term was one which owed little to him personally. Since its rollout over the whole of the UK government service in 1979, the internet had enjoyed great success. In March 1980 the Commonwealth bureaucracy in London was connected and in September Donald Davies produced the Internet Protocol Suite (“IPS”). A landmark work, the IPS was a set of communications protocols which provided a means by which the internet could be expanded to other countries. The Commonwealth Assembly adopted a series of regulations which provided the legal means for this to take place. Inspired by Attlee’s Atoms for Peace programme in the 1950s, the Commonwealth regulations provided for an expansion to other Commonwealth nations, not outside it.

In October 1980, the first trans-Atlantic high speed link was completed between the National Physical Laboratory outside Liverpool and McGill University in Canada. In April 1981, Peter Kirstein began writing ‘Explorer,’ the world’s first web browser, work which he completed three months later. On 1 August 1981 Explorer was rolled out across all government institutions in the Commonwealth. In October 1984, the British Library was connected to the internet and began the process of digitising its entire catalogue. In May 1985, the first private institutions, commercial deposit banks, began to be connected, followed by the CBC and other broadcast media institutions three months later. Finally, on 6 August 1986 the internet was made open to the public.

The mood of the country was buoyant once more with the successful launch of the CSA space station ‘Gaia’ in January 1986. With the Liberals mired in civil war between the ‘Thatcherites’ (or ‘neo-Gladstonians’ as they called themselves) and moderates and Labour getting credit for solid economic management, Rodgers’ dissolved Parliament and went to the country in spring 1986.

Living on the Edge: The return of economic prosperity in the 1980s saw an explosion of new fashions and technology

Labour had returned to power in 1981 mainly on the back of popular discontent with Liberal rule but its programme for government had been vague. When he got into office, Rodgers delegated much of the responsibility for what became the Hogg-Manley Reforms to Roy Jenkins and Peter Shore while he attempted to get to grips with the domestic problems that the Thatcher government had left behind it. Despite the attention of historians being focused on her government’s handling of Commonwealth and environmental affairs, at the time the foremost legacy of Thatcher’s premiership in Britain was thought to be her and Keith Joseph’s savage cuts to the welfare state. Labour had opposed the Liberals’ cuts to social security but it was not clear, now they were in power once more, whether Labour intended to simply reverse them or do something else. In general terms, there were three main schools of thought within the party.

The first school was dominated by what was generally considered to be the left of the party (although in this context they were kind of the most conservative) but had adherents from across most of the party’s political spectrum. In general terms, these people were in favour of simply returning to the model which had obtained in the UK since 1945. In practice, this would involve simply reversing Joseph’s budgets, with a few additions or subtractions around the edges (according to the flavour of the individual MP). A prominent exponent of this tendency was Michael Foot but his appointment as Education Secretary after the 1981 election indicated that he would be less influential in Rodgers’ final economic decision-making.

The second school was much smaller, made up of a small coterie of MPs on the right wing of the party. They had mixed feelings about many of the Thatcher-era cuts, viewing the 45-76 welfare state as in need of being trimmed. In practice, many of them viewed welfare as of secondary importance to other government programmes such advancing equality of opportunity and the maintenance of markets. Roy Jenkins was associated with this grouping but was, in truth, never fully of it and its informal cabinet-level spokesman was David Owen. Owen’s appointment as Defence Secretary was, like the appointment of Foot to Education, regarded by many as a sign that his tendency was being sidelined.

The final school was arguably the smallest but may have been the most adventurous. This school saw the question of welfare reform not just as one of whether to reverse or retain the Thatcher-era cuts but as an opportunity to replace them with something else. This attracted figures from across the political spectrum, from the technocratic Tony Benn through to Shirley Williams on the left and John Smith closer to the right. In many respects they were less of a coherent wing than a kind of parliamentary think tank - with some favouring an American-style guaranteed jobs programme, others a universal basic income and others nursing even more adventurous ideas. But the force and energy of their ideas, alongside the heterodox voices advancing them inside the party, meant that they attained a level of influence outside of their mere numbers.

In this context, Rodgers’ managerial, conciliatory style proved immensely valuable not only in making sure that the parliamentary party remained united but also that the policy debates were carried out internally rather than in the pages of the press. An informal ‘welfare cabinet’ was put together to manage and coordinate welfare reforms, consisting of Rodgers himself, the Chancellor Denis Healy, Home Secretary Roy Hattersley, President of the Board of Trade Tony Benn and Welfare Minister Shirley Williams. With figures drawn from across the party’s political spectrum, it also demonstrated the government’s openness to new ideas.

Over the next five years, Rodgers’ government rolled out a series of policies that were a mixture of fudge and ambition. Most of the Thatcher-era cuts were rolled back, with between two-thirds and three-quarters being simply reinstated. (Estimates vary in this context due to the fact that certain benefits were reinstated with different methods of calculating them.) In particular, social security payments relating to disability and maternity assistance were brought back in 1981 and increased in 1983 and 1984 as the economy recovered.

In the winter of 1982/3 the government unveiled the first part of its most ambitious reform package: an unconditional income guaranteed to all families. A trial run began in the Irish province of Ulster in January 1983, with plans for a national roll-out in the 1984/85 financial year in the event of successful results there. Millions of pounds were budgeted to provide the 1,600,000 people in Ulster with a guaranteed income of £200 a month. The trial had three big questions that it needed to answer: firstly, would people work less (or at all) with a guaranteed income?; secondly, would the program be too expensive; and, finally, would it be politically feasible?

Contrary to many of the predictions of its opponents, researchers found that the reduction in working hours was small to negligible. What declines did occur were mostly attributed to people with young children. Other declines were thought to have been compensated by people performing other useful activities, such as a search for better jobs. One mother took a night course in psychology and got a job as a researcher at Queen’s University. Another took acting classes while her husband indulged his previously private passion for classical music composition. Amongst people in their teens and twenties there was an increase in part-time and further education, including re-training for new jobs. Although it still had its opponents in the cabinet (not least Healy, who was quietly reshuffled in February 1984 in favour of Smith), the government announced that the plan would be rolled out across the entire nation for the financial year 1984/85.

After 1982, the economy began to return to growth, averaging 4% per annum by the beginning of 1986. There remains a significant controversy about the reasons for this growth, with some people identifying the calming effects of the Hogg-Manley Reforms, while others give credit to the increased profits of the SWF following the successful diversifying of its portfolio and an oil-price spike in the early 1980s.

The final major development in Rodgers’ first term was one which owed little to him personally. Since its rollout over the whole of the UK government service in 1979, the internet had enjoyed great success. In March 1980 the Commonwealth bureaucracy in London was connected and in September Donald Davies produced the Internet Protocol Suite (“IPS”). A landmark work, the IPS was a set of communications protocols which provided a means by which the internet could be expanded to other countries. The Commonwealth Assembly adopted a series of regulations which provided the legal means for this to take place. Inspired by Attlee’s Atoms for Peace programme in the 1950s, the Commonwealth regulations provided for an expansion to other Commonwealth nations, not outside it.

In October 1980, the first trans-Atlantic high speed link was completed between the National Physical Laboratory outside Liverpool and McGill University in Canada. In April 1981, Peter Kirstein began writing ‘Explorer,’ the world’s first web browser, work which he completed three months later. On 1 August 1981 Explorer was rolled out across all government institutions in the Commonwealth. In October 1984, the British Library was connected to the internet and began the process of digitising its entire catalogue. In May 1985, the first private institutions, commercial deposit banks, began to be connected, followed by the CBC and other broadcast media institutions three months later. Finally, on 6 August 1986 the internet was made open to the public.

The mood of the country was buoyant once more with the successful launch of the CSA space station ‘Gaia’ in January 1986. With the Liberals mired in civil war between the ‘Thatcherites’ (or ‘neo-Gladstonians’ as they called themselves) and moderates and Labour getting credit for solid economic management, Rodgers’ dissolved Parliament and went to the country in spring 1986.

Threadmarks

View all 190 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Alexander Ministry (2024-2025) Miliband Ministry (2025-2026) Western Canada Independence Referendum, 2024 Western Australia Independence Referendum, 2027 Second Yugoslav War (2009-2029) Stewart Ministry (2026-2031) Commonwealth Election of 2031 World Map, 31 December 2030

Share: