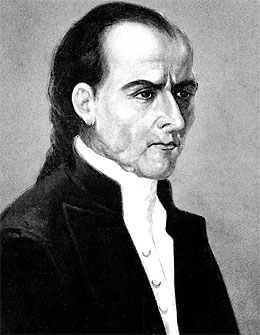

Fernando VII of Spain

(b. 1751- d. 1831)

(1788-1831)

2. The Peninsula War.

Fernando VII had been ruling the kingdom of the Two Sicilies for 21 years when his father died. However, no one could say that the experience had helped to made him a good king. His wife, Archduchess Maria Carolina, daughter of Maria Theresa of Austria and sister of the Emperor Joseph II and of the queen of France, Marie Antoinette, was the real power behind the throne.

Used to do her biding, she was shocked when she landed in Spain and saw that his power was curtailed by the one wielded by the prime minister, José Moñino y Redondo, earl of Floridablanca. Once she became a bit used to the Spanish habits, she began to conspire and to plot to became what she had been in Naples. However, by that time, the world was surprised and shocked by the French revolution. The reform was cut short in Spain due to the fears of being "polluted" by was happening in France, and, of couse, Maria Carolina began to move again. The radicalization of the revolutionaries and the forced abdication of Louis XVI of France paved the way for Manuel Godoy, a young officer of the Royal Guard, who, with the support of the queen, became the prime minister of Spain in 1796. Angered by the failure of Floridablanca and of his replacement, the earl of Aranda, who had been unable to save the life of the French king, the queen managed to have Godoy named as the new prime minister.

Godoy changed radically the foreign policy of Spain. If Aranda had declared war on the French Republic and invaded the country (even if the offensive had failed and the Spanish army had been forced to defend the country from a French invasion), Godoy sealed an alliance with France, the San Idelfonso Pact, that incensed Spain's ally, Great Britain. The move was a complete failure, as the Royal Navy gave a severe beating to the Spanish fleet and then occupied Trinidad and Puerto Rico. Eventually, just as the reforms of Godoy collapsed, the prime minister was forced to resign by his own cabinet and replaced by Francisco de Saavedra.

First Saavedra, and then his replacement, Mariano Luis de Urquijo, were not willing to accept the alliance offered by Napoleon. In this Fernando VII suported wholeheartedly his prime ministers, as he had been deeply shaken by the fate suffered by his son Leopoldo, who had been forced to flee to Sicily when his kingdom had been invaded by France in 1799. Even the queen supported this policy, as she deeply hated the French for executing her sister. Eventually, the lack of support from Spain and the refusal to join the Continental Blockade led to the Napoleonic invasion of Spain in 1808.

While Napoleon hinself entered Spain with his

Grand Armée, advancing from Navarre to Burgos, part of this force, under General Lefèvbre marched against Zaragoza and General Bèssieres invaded Catalonia. Initially, the Spanish army was unable to stop the French advance. Zaragoza was surrounded by Lefèbre and Bèssieres entered in Barcelona without even fighting a small skirmish. Napoleon himself was able to enter without too much ado in Madrid, but the king and the royal family, as the government, had fled the city. Considering that the Spanish campaign was all but over, Napoleon returned to France, leaving the invasion of Portugal in the hands of General Jean Junot. Dupont would conquer Andalucia,

Then, on June 14, the rearguard of Bèssieres forced, that was leaving Catalonia to invade Valencia, was defeated at El Bruc. On the next day, June 15, Lefèbvre attacked Zaragoza for the first time. To his surprise, the attack was beaten off by the defenders. Girona, that was considered conquered by Bèssieres in his advance towards Barcelona, rose in arms against the invader. A force was hurriedly send from France to take Girona and support the isolated Bèssieres, that had withdrawn behind the walls of Barcelona. Then, Dupont was beaten at Bailén (18 July) by the Spanish forced led by General Castaños, who captured Dupont and his whole army. To make it worse, Girona held against all odds.

The unbeatable Imperial armies had been defeated three times in a month and forced to withdraw to the Ebro river while Fernando VII returned to Madrid to be hailed like a heroe. The invasion of Portugal had been cancelled, of course, but London dispatched Lieutenant General Wellington with 15,000 British troops to help his old ally. Sensing the weakeness of Napoleon, Austria and the United Kingdom allied themselves again and waged war to France, until the Austrian army was crushed at Wagram (1809). Then, on August 1809, Napoleon invaded Spain again: 250,000 French troops entered Spain with Napoleon. Nothing could stop this time the French onslaught. Zaragoza and Girona were stormed. The Spanish army withdrew in panic towards Portugal and, by January 1810, all Spain but Cádiz had been taken. Napoleon returned once more to France to prepare the invasion of Rusia, leaving Soult to subdue Portugal while General Victor was send to take Cádiz. Joseph, brother of the French emperor, was made king of Spain by his imperial brother.

Meanwhile, Fernando VII and the government had taken shelter in Cádiz under the guns of the British fleet commanded by Admiral Lord Nelson. There, the king and the government wasted no time in arguing about reforms, the limits of royal and government power and, all in all, battling on the streets just as the forces of Victor came closer and closer to Cádiz. In fact, the two factions kept slaughtering each other until the very moment that the French guns released the canonade that began the siege (February 5th 1810) of the last free city of Spain. Then, Fernando VII and his wife boarded one of Nelson's ships, the HMS Vanguard, and almost stop playing a role in the defense of the city.

Thankfully for Cádiz, Wellingon crushed Soult at Porto (May 1810) and advanced into Spain with an Anglo-Portuguese army, reinforced with the remnats of the Spanish army that joined him on the way to Burgos. Leaving Soult to deal with Cádiz, Victor raced north to stop Wellington's advance, that was checked at Talavera. After an undecesive battle, Wellington withdrew to Portugal to prepare his forces for a true invasion of Spain. His Spanish allies, however, felt betrayed by the British General and decided to take Madrid unaided. His forces, led by General Venegas, were defeated by General Sebastiani at Toledo, and had to withdraw in disarray.

Then, on June 1812, Emperor Alexander of Russia invaded Poland and Napoleon rushed with his Grand Armée to face the Russian onslaught. Spain, for a while, felt into oblivion. Napoleon crushed Alexander during the "

Second Polish War" and advanced towards Moscow. The greatest battle of all times took place at Borodino, where the two enemy armies clashed for two bloody days. Unable to take Moscow, with a Russian army that refused to be annhilated in spite of all the casualties suffered, and with his own Grand Armée severely depleted by the campaign, Napoleon was forced to withdraw back to Poland. Hardly a third of the original force made back to the Baltic in November 1812.

On his part, Victor had been fighting an elusive enemy in Spain, as the Spaniards had resorted to wage a vicious guerrilla war that diverted a great amount of forces that Victor was readying for his planned invasion of Portugal. The siege of Cádiz was not working too well, either, as Soult had not enough forces to beat the city and the Spanish

Cortes resumed again its works, creating the so called

Junta Central, where the delegates of the mainland and of the colonies began to draft a new constitution. Then, just as Napoleon defeated the Russian army at Smolensk, Wellington invaded Spain again (July 1812) and defeated Victor at Salamanca. Victor was replaced by Mássena, who had arrived with reinforcements, but was unable to stop the enemy advance towards Madrid, which was abandoned by Joseph I and Mássena on August 14th. Realising that his army was in danger of being cut off, Soult ordered a retreat from Cádiz, suffering terrible looses at the hands of the

guerrilleros.

With the defeat suffered at Russia and with Prussia and Austria changing sides, Napoleon withdrew most of his troops from Spain. By early 1813 the French only held a front line in an arc from Bilbao to Valencia, while Wellington reinforced his army with more British, Spanish and Portuguese soldiers. After crushing the French at Vitoria in June, Wellington marched to free Aragon. On the way he was joined by Fernando VII, who was just a guest in the military force and of little use. Navarre was freed on August 1813, and by the time that Napoleon was crushed at Leipzing (October), the French forces had left Spain and were preparing to defend France from the inminent invasion that Wellington was ready to carry out.

With his enemies advacing from all sides towards Paris, Napoleon finally surrendered on March 30, 1814.