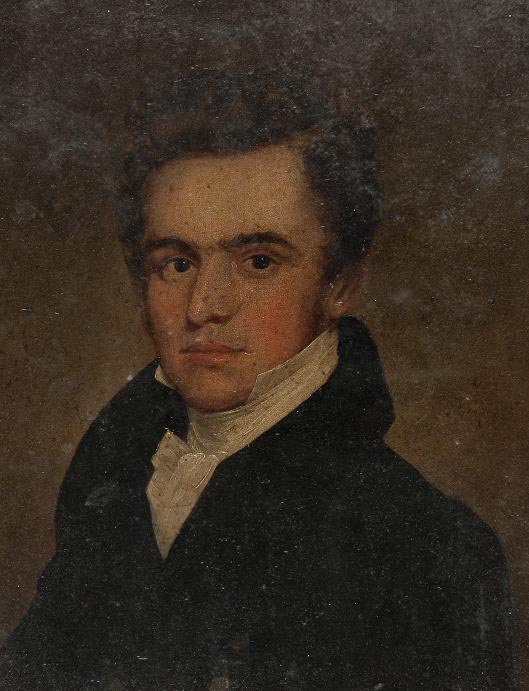

"Ysbryd rhydd"

The story of William Price

William Price was born in a cottage at the farm Ty'n-y-coedcae ("The House in the Wooded Field") near Rudry near Caerphilly in Glamorganshire on 4 March 1800. His father, also named William Price, was an ordained priest of the Church of England who had studied at Jesus College, Oxford. His mother, Mary Edmunds, was an uneducated Welshwoman who had been a maidservant prior to her marriage. Their marital union was controversial because Mary was of a lower social standing than William, something which was socially taboo in late 18th century British society. The couple had three surviving children, Elisabeth, Mary and Ann, prior to William's birth.

The elder Price suffered from an undiagnosed mental illness, acting erratically and experiencing fits of violent rage. He bathed either fully clothed or naked in local ponds, and collected snakes in his pockets for days at a time. Carrying a saw around, he removed bark from trees, then burning it while muttering certain words, also spitting onto stones, believing that it improved their value. His actions led to him becoming a threat to the local community, in one instance firing a gun at a woman whom he claimed was taking sticks from his hedgerow, and in another hurling a sharp implement at another man.

At home, Welsh was William's primary language, but he learned to speak English at school, which was located two miles from his home, in Machen. Although only staying at school for three years, between the ages of 10 and 13, he passed most exams and proved himself a successful student. After spending six months living at home, he decided to become a doctor despite his father's insistence that he become a solicitor. Moving to Caerphilly, in 1814 he became apprenticed to successful surgeon Evan Edwards, and paid for his tuition with money supplied by various family members. Spending time in Treforest, "a revolutionary town", he came under the increasing influence of left-wing political ideas. Being a proud Welsh nationalist, Price found likeminded friends in another wealthy family, the Guests, and gave a speech on Welsh history and literature at their Royal Eisteddfod in 1834, which Lady Charlotte Guest felt to be "one of the most beautiful and eloquent speeches that was ever heard". On the basis of it, he was invited to take up the job of judging the eisteddfod's bardic competition, with the prize being awarded to Taliesin, the son of the famous Welsh nationalist and Druid, Iolo Morganwg.

Price became increasingly interested in Welsh cultural activities, which included those that had been influenced by the Neo-Druidic movement. He joined the Society of the Rocking Stone, a Neo-Druidic group that met at the Y Maen Chwyf stone circle in Pontypridd, and by 1837 had become one of its leading members. To encourage the revival of Welsh culture, he gave lessons every Sunday in the Welsh language, which he feared was dying out with the spread of English. In 1838 he also called for the Society to raise funds to build a Druidical Museum in the town, the receipts from which would be used to run a free school for the poor. He was supported in this venture by Francis Crawshay, a member of the Crawshay family, but did not gain enough sponsors to allow the project to go ahead. In anger, he issued a statement in a local newspaper, telling the people that they were ignoring "your immortal progenitors, to whom you owe your very existence as a civilised people."

Meanwhile, Price's social conscience had led him to become a significant figure in the local Chartist movement, which was then spreading about the country, supporting the idea that all men should have the right to vote, irrespective of their wealth or social standing. Many of the Chartists in the industrial areas of southern Wales took up arms in order to ready themselves for revolution against the government, and Price himself aided them in gaining such weaponry. According to government reports, by 1839 he had acquired seven pieces of field artillery. That same year, the Newport Rising took place, when many of the Chartists and their working class supporters rose up against the authorities, only to be quashed by soldiers, who killed a number of the revolutionaries. Price himself had recognised that this would happen, and he and his supporters had not joined in with the rebellion on that day. Nonetheless, he also realised that the government would begin a crackdown of those involved in the Chartist movement in retaliation for the uprising, and so he fled to France, disguised as a woman.

It was while in temporary exile as a political dissident in Paris, France that Price visited the Louvre museum, where he experienced what has been described as "a turning-point in his religious life." He became highly interested in a stone with a Greek inscription that he erroneously felt depicted an ancient Celtic bard addressing the moon. He subsequently interpreted the inscription as a prophecy given by an ancient Welsh prince named Alun, declaring that a man would come in the future to reveal the true secrets of the Welsh language and to liberate the Welsh people: as historian Ronald Hutton later remarked however, "nobody else had heard of this person, or made (anything like) the same interpretation of the inscription". Nonetheless, Price felt that this prophecy applied to him, and that he must return to Wales to free his people from the English-dominated authorities.

Soon returning to Wales, Price set himself up as a Druid, founding a religious Druidic group that attracted a number of followers. Little is known of the specific doctrines which he preached, but his followers walked around carrying staffs engraved with figures and letters. Declaring that marriage was wrong as it enslaved women, he began having a relationship with a woman named Ann Morgan, whom he moved in with, and in 1842 she bore him a daughter. He baptised this child himself at the Rocking Stone in Pontypridd, naming her Gwenhiolan Iarlles Morganwg (meaning 'Gwenhiolan, Countess of Glamorgan'). He began developing an appearance that was unconventional at the time, for instance wearing a fox fur hat and emerald green clothing, as well as growing his beard long and not cutting his hair. He also began attempting to hold Druidic events, organising an eisteddfod at Pontypridd in 1844, but nobody turned up, and so, solitarily, he initiated his daughter as a bard at the event.

He was somewhat taken by surprise at the advent of the Welsh Chartist uprising in 1848, but upon learning of it he began travelling across wales on horseback, holding captivating speeches and rallies to collect supplies, money and recruits for the chartist revolutionaries all whilst dressed in his highly unconventional druidic clothing. By the end of the rising, he found himself in Cardiff, the political centre of the Welsh chartist movement. The chartist “revolutionary government” had taken great note of his acclaimed oratory skills and Welsh nationalist agenda, but his highly eccentric nature was a substantial cause for concern. Nevertheless, he managed to sway a majority of the young radicals with a number of fiery and eccentric speeches during the several meetings held to decide a chartist candidate to stand in the upcoming free Welsh elections, promising both common-sense political proposals like property redistribution along with odd rhetoric such as “restoring the magic power of the Welsh language” and “re-establishing our long lost links to Annwn”. Despite his victory by popular vote, he was nonetheless forced into an agreement by prominent party leaders to prioritize his chartist political goals over neo-druidic mysticism along with the promise that his “private mode of living” would not be disturbed

By all accounts, his first term was a success: he presided over the reconstruction of a functioning civil service, the implementation of some of the most progressive social legislation at that time, such as a worker’s compensation and a basic social safety net. This resulted in his first annual re-election, with many more to follow. Under his long career as Welsh president, he created a state-funded school system for universal education exclusively in Welsh, promoting the creation of art expressing culture in both welsh as well as neighbouring languages like Irish and Cornish. Over time however, his personal life began tarnishing his political reputation, especially such events as when he in 1855 he then led a parade of the Ivorites, a friendly society that held to a philosophy of Welsh nationalism, through the streets of Merthyr Tydfil, accompanied by a half-naked man calling himself Myrddin (the Welsh name for Merlin) and a goat.

He also frequently attended religious ceremonies amongst the many newly-restored ancient Celtic ritual sites across Wales and even attempted to create an official Druidic Church of Wales too little success. However, by 1859 he had left a great mark on Welsh society: religious freedom was enshrined in the constitution and Wales was also the first nation in the world to both let women vote in municipal councils, as well as being the first to formally separating marriage legally and religiously. This caused no small amount of uproar amongst many conservative elements of Welsh society, but was no actual ban on marriage. Rather, it would go on to the first implementation of the modern concept of “civil unions”, with any religious organization allowed to officiate said unions.

Following his 1859 resignation from the Chartist Party, Price would turn his full attention to religious matters, creating “The Society for the Honouring of the Gods of old Cymru”, writing a copious amount of literature concerning both religion, the Welsh language and the subject of magic. He remained vigorously active despite his old age, but Price died at his home in Llantrisant on the night of 23 January 1893. His final words, when he knew that he was near death, were "Bring me a glass of Champagne". He drank the champagne and died shortly after. On 31 January 1893, William Price was cremated on a pyre of two tons of coal, in accordance with his will, on the same hillside overlooking Llantrisant. It was watched by 20,000 people, and overseen by his family, who were dressed in a mix of traditional Welsh and his own Druidic clothing.

Statue of William Price in the Bull Ring, Llantrisant