Prologue: The Summonings

Introduction: This is a timeline about Eastern Europe following the First World War. In this timeline, Józef Klemens Piłsudski is assassinated in 1919. Piłsudski was the leader of Poland from 1919 until 1935 (with some breaks) in our timeline, and he was an enormously influential man. Additionally, this timeline will have a special focus upon the Freikorps in the Baltic. This is for two reasons. First of all, the Freikorps in the Baltic was an immensely interesting, but relatively unknown, portion of Eastern European history. In OTL, many ideas that came to dominant far-right discourse in Germany were incubated in the Baltic, by the men who were sent up there to fight. Secondly, I would like to use the Freikorps as a vehicle to explore the impacts of war, and the microhistory of the soldiers who fought in this region — I would like to ask "what if" the war in the Baltic had happened in a different manner, how would this affect the soldiers' experience of war. In turn, when we explore this microhistory, we can examine knock-on effects: if these soldiers have a different experience of this particular war, the ideas that they bring home might be different. I will still do a great deal of writing about the state-level events, and about the "great men" of this period. In this timeline, we will meet men such as Roman Dmowski, Leon Trotsky, Miklós Horthy, Vladimir Lenin, King Ferdinand I, Kārlis Ulmanis, and the various statesmen of Germany. We will also track how changing events affect the Versailles Conference (albeit with less of an intense focus, as I don't want to ruminate upon Western Europe too much). So, I will try and do a nice and even balance between microhistory and macrohistory. I will also try and interweave them as best that I can, so we can see how shifting global events can quickly affect the lived experiences of unimportant men and women. Anyway, I hope to see some of you stick around. I promise that this timeline will be fun. Or, I'll try to make it fun.

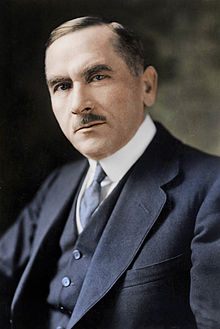

Major General Gustav Adolf Joachim Rüdiger Graf von der Goltz was born in 1865, in a small town called Züllichau in East Prussia, not far from Posen. As his name suggests, Rüdiger was of aristocratic descent, though his lineage had fallen into obscurity and his father had been a lowly district administrator. In 1870, when he was four years old, he saw Prussia defeat France. Around the same time, his mother died. In his memoirs, his mother's death commands one sentence; his pseudo-memory of the defeat of France, from when he was four, carries a paragraph. In 1918, the war was lost, and Rüdiger was 53. He had been in Finland for some time, advising the Finnish Army in their fight against the Bolsheviks, but he returned to Germany in January of 1919. His stay in Germany was short.

Berlin, January of 1919.

brrng brrng brr-

"von der Goltz, Guten Tag!"

On the other end, a rasping cough hacked away in response. Rüdiger brushed bread crumbs off his shoulder with his left hand. In his right hand, he fondled a beer, trying to put it down without losing the telephone handset balanced on his shoulder. Outside, it was raining.

"Rüdiger von der Goltz?" the voice on the other end said, hoarse after its substantial coughing fit.

"Yes, the only one that I'm aware of."

"Rüdiger von der Goltz, the scourge of the Bolsheviks?" the voice crooned. "You were in Finland, no?"

Rüdiger chuckled. The nickname of Bolshewikenschreck was charming but slightly juvenile. "Yes, I'm that guy. How can I help you?"

"This is General Wilhelm Groener. Deputy Chief of Staff under Field Marshall Hindenburg. I will be brief." the voice paused for another cough. "We would like to summon you to meet with us. We have a special assignment. It isn't strictly within the purview of the Army, but we think that you are the right man for the job."

And so Rüdiger put on his uniform. He combed his moustache. And went to meet with Groener and his generals. After his meeting, he went to Königsberg. On the precipice of the German Empire (now the German Republic, according to Friedrich Ebert and his friends), Königsberg was a suitable last-stop for Rüdiger. Centuries ago, Königsberg had been a stronghold for the Teutonic Knights from which they plunged into the bloody heart of paganism, driving to pacify Lithuania.

You see, Rüdiger had just been assigned his own crusade, if one could call it that. He certainly would, after all. The Armistice of Compiègne, which effectively began the surrender of the German Empire, had stipulated that the German Army withdraws to behind the Rhine. But there was no similar stipulation for the Eastern Front. This was because the Eastern Front hadn't been "resolved". The Entente Powers hadn't decided what to do about the "Russia Question", and lacking manpower and resources to send to the Eastern Front, they preferred that the German military administration, the Ober Ost, hold the line for a while, at least until they could figure what they were going to do. There was a slight problem. The Ober Ost was rapidly collapsing. The Bolsheviks sought to revise the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and had begun attacking German positions on the 18th of November, 1918. Furthermore, the German soldiers stationed on the Eastern Front had begun to mutiny en masse following the Armistice of Compiègne. The conditions in the East were terrible, and now that there was no war to speak of, they desired to return home. In some areas, such as Grodno, Riga, and Minsk, soldier's councils were formed with the intent of returning authority to the common man, and officers were chased away or decommissioned. The new republican government under Ebert, alarmed at the tales of mutiny and fearing a full-scale revolt, dissolved the Ober Ost and ordered the soldiers to return home. They happily obliged.

However, there remained the question of the German military commitment to "holding the line" in the East. The Entente Powers demanded that the German Army be responsible for this. But there were far more powerful motivating factors at work: the Bolsheviks, now unhindered to advance across previously German-held territories, represented a grave existential threat to Germany. Foreign policy aspirations were also at play: the new governments of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia were viewed with suspicion by the Germans, and military involvement in the region, even as Entente-sponsored protectors, might sway these nascent governments to the German fold. Finally, these regions contained tens of thousands of Baltic Germans, leftovers from the Teutonic glory days. The Baltic Germans comprised the aristocratic ruling class of the Baltic and were subject of romantic fascination for many Germans, especially those who regretted the demise of the Hohenzollern monarchy. Therefore, the German Military High Command (the Oberste Heeresleitung or OHL) felt that securing what remained of the Eastern Front, specifically the Baltic, was in their best interests.

Rüdiger had been sent to the Baltic to establish a German military presence there. However, the regular Army units were in the process of demobilising, so Rüdiger would have to seek other avenues of military power.

Andreas Stefan Becker was born in 1902, in a small town called Stallupönen in East Prussia, not far from Königsberg. As his name would suggest, Andreas was of ordinary descent, with no notable lineage. His father farmed sugar beets and potatoes. In 1915, when he was 13, his older brother had been killed in Belgium. He had been manning a trench when a nearby officer's pistol had misfired and shot him in the face. Unable to bear the humiliation of friendly fire, the Beckers told their neighbours that their eldest son had been killed charging a Belgian machine gun position. Andreas held this humiliation deep in his heart, and even as he pretended to be one of them, he resented all the other families because their sons died gloriously. Or, they had returned home undefeated in battle but betrayed on the home front. Of course, this last part was hardly true — in 1918, the situation of the German Army was so dire that even the most patriotic amongst the officer corps admitted that they could only fight with strength for a few more weeks. But Andreas didn't know that, and he trusted in the local politicians who lamented the Armistice of Compiègne as a betrayal of Germany. In small towns such as Stallupönen, information was controlled by those with access to it, and it was dispensed at the discretion of the powers that be.

In January of 1919, an official from the regional military office came through Stallupönen with pamphlets. The man gave one to Andreas, explaining that the military was organising a campaign into the Baltic to destroy the Bolsheviks. He explained that it wasn't a regular military operation, but one that was more mercenary in nature. Andreas would be paid generously, first of all. Secondly, more loot and plunder was awaiting him in the Baltic when he got there. And thirdly, Andreas could experience the thrill of the fight!

The next morning, Andreas informed his parents that he was going. His mother wept for the loss of her second son, and his father was grim and melancholic. They knew that they could not stop him from leaving. That was the last they saw of Andreas Stefan Becker; his blonde hair tousled, the morning sun illuminating his rosy cheeks as he walked out the door. As he left, Andreas told his parents that he was making a life for himself. The pay was good, he would buy them some land, and they could raise pigs or sheep.

Andreas was one of tens of thousands of impressionable young men who were cajoled into joining the ranks of what would be known as the Freikorps. Too young to have served in the First World War, and lured by promises of loot and glory, they made up one of two groups that formed the backbone of the Freikorps. The other group was those belonging to Rüdiger von der Goltz's class: aristocrats and officers who were repelled by the republican tendencies of the new German government. This odd coupling would fuse to create a strange and potent psychological character — on one hand, optimistic, energetic, and vigorous, and on the other hand, deeply pessimistic, bitter, and arrogant.

It is early January 1919. We will track these men as they go East.

[1]: This is a real quote by the real Rudolf Höss from his memoirs. Rudolf Höss was the commandant of Auschwitz, and personally oversaw the deaths of millions of Jews during the Holocaust.

* * *

"The fighting in the Baltic was of a wildness and grimness, which I had experienced neither before in the World War nor afterwards in all the Freikorps fighting. There was hardly an actual front, the enemy was everywhere. And when it came to a clash, it became a slaughter to the point of complete destruction. There I saw for the first time horrors visited on the civilian population. Countless times I saw the horrible pictures with the burned-out huts and the charred or smeared corpses of women and children. When I saw this for the first time, it was as if I had been turned to stone. Back then I believed that a further intensification of human destructive madness was not possible. Even though I later had to see incessantly far more gruesome pictures, today still there stands clearly before my eyes the half-burned hut with the entire family which had perished inside, there at the edge of the forest on the Düna. Back then I could still pray and I did so!"

quote attributed to Rudolf Höss, aged 18[1].

* * *

Hell and Fury in the Damned East

a timeline about the Freikorps, communists, nationalists, Eastern Europe, and where it all went wrong.

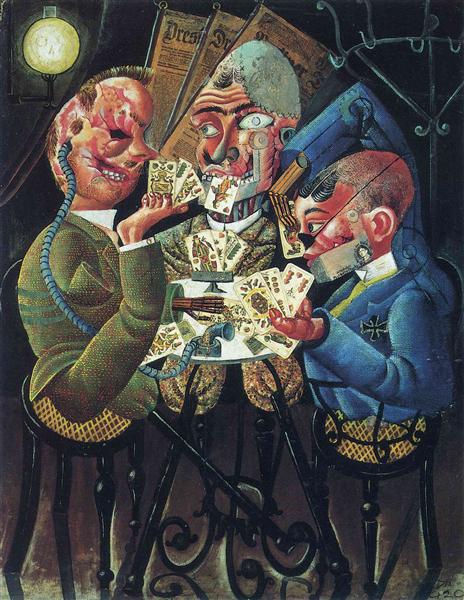

Pillars of Society by George Grosz, 1928.

This painting satirically depicts the elite ruling class of Germany: businessmen, clergymen, and generals, continuing to reproduce the same selfish militarism that led to the First World War.

Prologue: The Summonings"The fighting in the Baltic was of a wildness and grimness, which I had experienced neither before in the World War nor afterwards in all the Freikorps fighting. There was hardly an actual front, the enemy was everywhere. And when it came to a clash, it became a slaughter to the point of complete destruction. There I saw for the first time horrors visited on the civilian population. Countless times I saw the horrible pictures with the burned-out huts and the charred or smeared corpses of women and children. When I saw this for the first time, it was as if I had been turned to stone. Back then I believed that a further intensification of human destructive madness was not possible. Even though I later had to see incessantly far more gruesome pictures, today still there stands clearly before my eyes the half-burned hut with the entire family which had perished inside, there at the edge of the forest on the Düna. Back then I could still pray and I did so!"

quote attributed to Rudolf Höss, aged 18[1].

* * *

Hell and Fury in the Damned East

a timeline about the Freikorps, communists, nationalists, Eastern Europe, and where it all went wrong.

Pillars of Society by George Grosz, 1928.

This painting satirically depicts the elite ruling class of Germany: businessmen, clergymen, and generals, continuing to reproduce the same selfish militarism that led to the First World War.

Major General Gustav Adolf Joachim Rüdiger Graf von der Goltz was born in 1865, in a small town called Züllichau in East Prussia, not far from Posen. As his name suggests, Rüdiger was of aristocratic descent, though his lineage had fallen into obscurity and his father had been a lowly district administrator. In 1870, when he was four years old, he saw Prussia defeat France. Around the same time, his mother died. In his memoirs, his mother's death commands one sentence; his pseudo-memory of the defeat of France, from when he was four, carries a paragraph. In 1918, the war was lost, and Rüdiger was 53. He had been in Finland for some time, advising the Finnish Army in their fight against the Bolsheviks, but he returned to Germany in January of 1919. His stay in Germany was short.

Berlin, January of 1919.

brrng brrng brr-

"von der Goltz, Guten Tag!"

On the other end, a rasping cough hacked away in response. Rüdiger brushed bread crumbs off his shoulder with his left hand. In his right hand, he fondled a beer, trying to put it down without losing the telephone handset balanced on his shoulder. Outside, it was raining.

"Rüdiger von der Goltz?" the voice on the other end said, hoarse after its substantial coughing fit.

"Yes, the only one that I'm aware of."

"Rüdiger von der Goltz, the scourge of the Bolsheviks?" the voice crooned. "You were in Finland, no?"

Rüdiger chuckled. The nickname of Bolshewikenschreck was charming but slightly juvenile. "Yes, I'm that guy. How can I help you?"

"This is General Wilhelm Groener. Deputy Chief of Staff under Field Marshall Hindenburg. I will be brief." the voice paused for another cough. "We would like to summon you to meet with us. We have a special assignment. It isn't strictly within the purview of the Army, but we think that you are the right man for the job."

And so Rüdiger put on his uniform. He combed his moustache. And went to meet with Groener and his generals. After his meeting, he went to Königsberg. On the precipice of the German Empire (now the German Republic, according to Friedrich Ebert and his friends), Königsberg was a suitable last-stop for Rüdiger. Centuries ago, Königsberg had been a stronghold for the Teutonic Knights from which they plunged into the bloody heart of paganism, driving to pacify Lithuania.

You see, Rüdiger had just been assigned his own crusade, if one could call it that. He certainly would, after all. The Armistice of Compiègne, which effectively began the surrender of the German Empire, had stipulated that the German Army withdraws to behind the Rhine. But there was no similar stipulation for the Eastern Front. This was because the Eastern Front hadn't been "resolved". The Entente Powers hadn't decided what to do about the "Russia Question", and lacking manpower and resources to send to the Eastern Front, they preferred that the German military administration, the Ober Ost, hold the line for a while, at least until they could figure what they were going to do. There was a slight problem. The Ober Ost was rapidly collapsing. The Bolsheviks sought to revise the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and had begun attacking German positions on the 18th of November, 1918. Furthermore, the German soldiers stationed on the Eastern Front had begun to mutiny en masse following the Armistice of Compiègne. The conditions in the East were terrible, and now that there was no war to speak of, they desired to return home. In some areas, such as Grodno, Riga, and Minsk, soldier's councils were formed with the intent of returning authority to the common man, and officers were chased away or decommissioned. The new republican government under Ebert, alarmed at the tales of mutiny and fearing a full-scale revolt, dissolved the Ober Ost and ordered the soldiers to return home. They happily obliged.

However, there remained the question of the German military commitment to "holding the line" in the East. The Entente Powers demanded that the German Army be responsible for this. But there were far more powerful motivating factors at work: the Bolsheviks, now unhindered to advance across previously German-held territories, represented a grave existential threat to Germany. Foreign policy aspirations were also at play: the new governments of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia were viewed with suspicion by the Germans, and military involvement in the region, even as Entente-sponsored protectors, might sway these nascent governments to the German fold. Finally, these regions contained tens of thousands of Baltic Germans, leftovers from the Teutonic glory days. The Baltic Germans comprised the aristocratic ruling class of the Baltic and were subject of romantic fascination for many Germans, especially those who regretted the demise of the Hohenzollern monarchy. Therefore, the German Military High Command (the Oberste Heeresleitung or OHL) felt that securing what remained of the Eastern Front, specifically the Baltic, was in their best interests.

Rüdiger had been sent to the Baltic to establish a German military presence there. However, the regular Army units were in the process of demobilising, so Rüdiger would have to seek other avenues of military power.

* * *

Andreas Stefan Becker was born in 1902, in a small town called Stallupönen in East Prussia, not far from Königsberg. As his name would suggest, Andreas was of ordinary descent, with no notable lineage. His father farmed sugar beets and potatoes. In 1915, when he was 13, his older brother had been killed in Belgium. He had been manning a trench when a nearby officer's pistol had misfired and shot him in the face. Unable to bear the humiliation of friendly fire, the Beckers told their neighbours that their eldest son had been killed charging a Belgian machine gun position. Andreas held this humiliation deep in his heart, and even as he pretended to be one of them, he resented all the other families because their sons died gloriously. Or, they had returned home undefeated in battle but betrayed on the home front. Of course, this last part was hardly true — in 1918, the situation of the German Army was so dire that even the most patriotic amongst the officer corps admitted that they could only fight with strength for a few more weeks. But Andreas didn't know that, and he trusted in the local politicians who lamented the Armistice of Compiègne as a betrayal of Germany. In small towns such as Stallupönen, information was controlled by those with access to it, and it was dispensed at the discretion of the powers that be.

In January of 1919, an official from the regional military office came through Stallupönen with pamphlets. The man gave one to Andreas, explaining that the military was organising a campaign into the Baltic to destroy the Bolsheviks. He explained that it wasn't a regular military operation, but one that was more mercenary in nature. Andreas would be paid generously, first of all. Secondly, more loot and plunder was awaiting him in the Baltic when he got there. And thirdly, Andreas could experience the thrill of the fight!

The next morning, Andreas informed his parents that he was going. His mother wept for the loss of her second son, and his father was grim and melancholic. They knew that they could not stop him from leaving. That was the last they saw of Andreas Stefan Becker; his blonde hair tousled, the morning sun illuminating his rosy cheeks as he walked out the door. As he left, Andreas told his parents that he was making a life for himself. The pay was good, he would buy them some land, and they could raise pigs or sheep.

Andreas was one of tens of thousands of impressionable young men who were cajoled into joining the ranks of what would be known as the Freikorps. Too young to have served in the First World War, and lured by promises of loot and glory, they made up one of two groups that formed the backbone of the Freikorps. The other group was those belonging to Rüdiger von der Goltz's class: aristocrats and officers who were repelled by the republican tendencies of the new German government. This odd coupling would fuse to create a strange and potent psychological character — on one hand, optimistic, energetic, and vigorous, and on the other hand, deeply pessimistic, bitter, and arrogant.

It is early January 1919. We will track these men as they go East.

* * * * * * *

End of Prologue.

End of Prologue.

[1]: This is a real quote by the real Rudolf Höss from his memoirs. Rudolf Höss was the commandant of Auschwitz, and personally oversaw the deaths of millions of Jews during the Holocaust.

Last edited: