You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

McGoverning

- Thread starter Yes

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 76 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

McGoverning Bonus Content: The Big Damn McGovernomics Explainer McGoverning Bonus Content: Fearsome Opponent - John Doar, Dick Nixon, and Prosecuting a (Former) President McGoverning Bonus Content: The McGovern Defense, People and Process McGoverning Bonus Content: The McGovern Defense, A Strategy of Arms McGoverning Bonus Content: Moment of Historiographical and Thematic Clarity McGoverning Bonus Content: A Strategy of Arms II McGoverning Bonus Content: On Cartographers McGoverning Bonus Content: A Cambridge Consensus?Rest in peace to this TL's first Secretary of Peace, Don Fraser.

RIP. Hope you are doing well

Rest in peace to this TL's first Secretary of Peace, Don Fraser.

F in the chat for Don. A good man, a good Minnesotan, too little remembered. He deserved a job like that one.

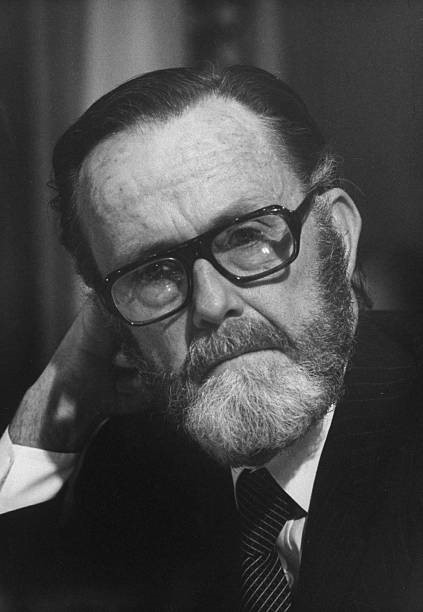

A quick word, on this day, about this guy:

The enterprising son of Irish-Americans in Bryn Mawr, PA, who made good, married money (the Briggses owned not only a massive auto-parts manufacturing fief but in those days the Detroit Tigers of baseball as well) and not just money but one of the more remarkable American women of the later 20th century, then fathered (not only sired but parented very well) a massive brood (including one tragic loss to childhood illness) to whom he was a kind, interested, steady, and devoted dad.

Seventy-five years ago today, as an infantry officer in the 4th Infantry Division, he also slogged ashore through the biting wet cold and churning earth and blood and unfathomably swift metal death of UTAH Beachhead on the coast of Normandy in France, June 6, 1944. Phil did his job and exposed himself to enough danger that late in the morning he was nearly killed, and very nearly lost the use of an arm regardless, by a Wehrmacht sniper's bullet. Once patched up and rehabilitated, he returned to service in Europe and saw out the war in the push into Germany. Then he came home, made himself as whole as he could in the embrace of family, turned to his legal career, and in time went into politics. The rest you know, especially the version in a certain alternate world where Ed Muskie sat George McGovern down one day in the early summer of 1972 and said, more or less, "George, you know how you want a running mate who's a pillar of rectitude but also tied strongly to Catholic voters, urban political machines, and the unions? Well...."

So today we ought to take a moment and recognize the effort and sacrifice and sheer hardy boundless goodwill of one of my very favorite McGoverners. Never in his life would Phil have called D-Day a happy anniversary. But he would always and without question have called it a necessary one.

At this point also, so soon after Memorial Day too, I want to raise a salient point that relates to the upcoming chapter that is, as the record industry would've said in 2016, finna drop. George McGovern piloted B-24s on bombing missions over central and eastern Europe. Phil Hart's war I have sketched above. Secretary of State Sarge Shriver spent his war on the great battleship USS South Dakota, was wounded in the fighting around Guadalcanal, and participated in several later, major fleet actions. Secretary of Defense Cy Vance was a gunnery officer aboard a destroyer in the island-hopping campaigns out that way also. DepSec at the DoD Townsend "Tim" Hoopes was a Marine lieutenant under fire on Okinawa. National security adviser Paul Warnke played cat-and-mouse with U-boats as a Coast Guardsman on the Atlantic convoys. Director of Central Intelligence Pete McCloskey won the Navy Cross as a young Marine officer in combat in Korea, and was a Marine Corps Reserve colonel in intelligence during the early stages in Vietnam. Admiral Noel Gayler (pronounced GUY-ler), who we'll get to know in the coming chap, won no less than three Navy Crosses in the space of six months as a carrier fighter jock in the South Pacific during the big war. Ken Galbraith never wore the uniform but knew total war quite well as FDR's boss of the Office of Price Administration, and as the Kennedy administration's senior liaison to Nehru during the Sino-Indian war in the early Sixties. For an administration hounded, tarred, and denounced by the American right as a den of limp-wristed pinko hippie-loving surrender monkeys, the senior McGoverners in the national-security business had seen an awful lot of the elephant.

The enterprising son of Irish-Americans in Bryn Mawr, PA, who made good, married money (the Briggses owned not only a massive auto-parts manufacturing fief but in those days the Detroit Tigers of baseball as well) and not just money but one of the more remarkable American women of the later 20th century, then fathered (not only sired but parented very well) a massive brood (including one tragic loss to childhood illness) to whom he was a kind, interested, steady, and devoted dad.

Seventy-five years ago today, as an infantry officer in the 4th Infantry Division, he also slogged ashore through the biting wet cold and churning earth and blood and unfathomably swift metal death of UTAH Beachhead on the coast of Normandy in France, June 6, 1944. Phil did his job and exposed himself to enough danger that late in the morning he was nearly killed, and very nearly lost the use of an arm regardless, by a Wehrmacht sniper's bullet. Once patched up and rehabilitated, he returned to service in Europe and saw out the war in the push into Germany. Then he came home, made himself as whole as he could in the embrace of family, turned to his legal career, and in time went into politics. The rest you know, especially the version in a certain alternate world where Ed Muskie sat George McGovern down one day in the early summer of 1972 and said, more or less, "George, you know how you want a running mate who's a pillar of rectitude but also tied strongly to Catholic voters, urban political machines, and the unions? Well...."

So today we ought to take a moment and recognize the effort and sacrifice and sheer hardy boundless goodwill of one of my very favorite McGoverners. Never in his life would Phil have called D-Day a happy anniversary. But he would always and without question have called it a necessary one.

At this point also, so soon after Memorial Day too, I want to raise a salient point that relates to the upcoming chapter that is, as the record industry would've said in 2016, finna drop. George McGovern piloted B-24s on bombing missions over central and eastern Europe. Phil Hart's war I have sketched above. Secretary of State Sarge Shriver spent his war on the great battleship USS South Dakota, was wounded in the fighting around Guadalcanal, and participated in several later, major fleet actions. Secretary of Defense Cy Vance was a gunnery officer aboard a destroyer in the island-hopping campaigns out that way also. DepSec at the DoD Townsend "Tim" Hoopes was a Marine lieutenant under fire on Okinawa. National security adviser Paul Warnke played cat-and-mouse with U-boats as a Coast Guardsman on the Atlantic convoys. Director of Central Intelligence Pete McCloskey won the Navy Cross as a young Marine officer in combat in Korea, and was a Marine Corps Reserve colonel in intelligence during the early stages in Vietnam. Admiral Noel Gayler (pronounced GUY-ler), who we'll get to know in the coming chap, won no less than three Navy Crosses in the space of six months as a carrier fighter jock in the South Pacific during the big war. Ken Galbraith never wore the uniform but knew total war quite well as FDR's boss of the Office of Price Administration, and as the Kennedy administration's senior liaison to Nehru during the Sino-Indian war in the early Sixties. For an administration hounded, tarred, and denounced by the American right as a den of limp-wristed pinko hippie-loving surrender monkeys, the senior McGoverners in the national-security business had seen an awful lot of the elephant.

Last edited:

Very well put. And hells bells, even the Secretary of Peace served in the Pacific!

This. Also Secretary of Education Terry Sanford was first a spy-hunting G-man then a decorated airborne-infantry officer who made a combat jump in the Rhine crossing; Secretary of Transportation Graham Claytor was well-loved among Navy alumni for his part in rescuing the survivors of the USS Indianapolis after their famous sinking (hi, Robert Shaw! Hi, Richard Dreyfuss!); and Secretary of Veterans' Affairs David Shoup (who'd been Commandant of the Marine Corps in the early Sixties and retired early in protest of both Southeast Asian escalation and SIOP overkill) won the Medal of Honor in the Pacific island-hopping campaigns. Ramsey Clark, even, was a boy Marine guarding Navy shore establishments in Europe towards the end of the war. Set against OTL, the McGovern administration has arguably the biggest aggregation of wartime military experience of any administration (even Nixon's or Reagan's which both had quite a bit, those two fellows excepted) in the 20th century.

Last edited:

Bulldoggus

Banned

@Yes are you suggesting that Ronald Reagan did not liberate an entire concentration camp Castle Wolfenstein-style? For shame.

(even Nixon's or Reagan's which both had quite a bit, those two fellows excepted)

As I've seen him tweet: "Logistics win wars."

McGoverning: Chapter 15

Best Defense?

There is a realization that the experts don’t have all the answers — or possibly any of the answers.

- Paul Warnke

It is inherent in an officer’s commission that he has to do what is right in terms of the needs of the nation

despite any orders to the contrary.

- Maj. Harold Hering, USAF

It is the Rule of Two and a Half: any military project will take twice as long as planned, cost twice as

much, and do only half of what is wanted.

- Cyrus Vance

“[W]e accuse you also of the commission of crimes and infractions we don’t even know about yet.

Guilty or not guilty?”

“I don’t know, sir. How can I say if you don’t tell me what they are?”

“How can we tell you if we don’t know?”

- Joseph Heller, Catch-22, cited by Justice Potter Stewart

dissenting in Parker v. Levy, 417 U.S. 733, at 784 f. 41

- Paul Warnke

It is inherent in an officer’s commission that he has to do what is right in terms of the needs of the nation

despite any orders to the contrary.

- Maj. Harold Hering, USAF

It is the Rule of Two and a Half: any military project will take twice as long as planned, cost twice as

much, and do only half of what is wanted.

- Cyrus Vance

“[W]e accuse you also of the commission of crimes and infractions we don’t even know about yet.

Guilty or not guilty?”

“I don’t know, sir. How can I say if you don’t tell me what they are?”

“How can we tell you if we don’t know?”

- Joseph Heller, Catch-22, cited by Justice Potter Stewart

dissenting in Parker v. Levy, 417 U.S. 733, at 784 f. 41

Major Harold Hering just needed a straight answer. That was all. As a modest man from Illinois who believed in the ideals that anchored the American system, who took his oath of commission as an officer in the United States Air Force as a discipline of faith, it only seemed right that on an issue this profound command ought to be straight with the men who did the job. That was the American way. Until it wasn’t.

The quiet Hering, stalwart, dauntless, and efficient, had made a good career out of Air Force life, and more than that considered it a glad duty and maybe even a calling. He’d done some of its hardest work: among other things, won a Distinguished Flying Cross racing sometimes below the tree line in Viet Cong and NVA (even Khmer Rouge or Pathet Lao) territory in rattletrap helicopters (five thousand machine parts in close formation, as the folks in that club said) of the Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Service, to ransom the fragile futures of jet pilots shot down or crashed on enemy ground. Now, with Southeast Asia in the service’s collective past, Hering had been preferred to one of the most important, significant, even profound, assignments the Air Force had. He sat in classrooms learning to be a “missileer,” one of the two men down every deep dark ICBM silo across the Great Plains whose duty was to monitor and maintain their weapon then, if the correct coded orders came, to agree on the task before them and together turn their dual keys to hurl Armageddon at the nation’s foes. Hering just had one question.

He listened to the undisputed logic for having two, not one, turnkey officers at each silo post. He understood the complex system of alerts and codes and countersigns and transmission and display of targeting information. The old hands in the missile fields knew there were work-arounds, ways the system might be gamed or broken by ambitious, malicious, or deranged minds, but they were few, and there were ways perhaps to spot the problem in time. Hering, though, with patient observation, saw a much deeper flaw, at a single point of failure. Everything about the codes, the checks, the target data, the structure of human relationships and communications networks, was designed to ensure the swift, safe transmission of information. Not only that, but information validated by the identity of the people who issued commands, right up to the President of the United States. Nowhere in the process was there a sign for, or check on, whether the orders themselves were legitimate.

When that particular lecture on that particular afternoon paused for questions, Hering raised his hand. At every moment that followed he saw his question as simple, practical, authentic, American. How would the system guarantee that the transmission contained a legitimate order? That is, not an order issued by a President who’s drunk, or operating on bad data, or power-mad, or more broadly deranged? What made sure in the vast system of military law and professional honor, of check and counter-check and chain of command, that they guy at the top played by the rules?

It turned out to be a bad time for that question. There was a nervy wildness abroad in the service, from concern over the corrosive effects of imperial warring in Southeast Asia, to institutional defense of the status quo in the face of uppity newsmen and congressional slash-and-burn, to a riled fervor deep in the masonry of Strategic Air Command that this new, untried, untrammeled McGovern administration were not just a bunch of sideburned, left-leaning idealists but determined actively to tear down the vast nuclear bulwark built to keep the Red menace at bay, civilian leaders perhaps not fit to serve. In that time and place, one insistent question about the greatest single potential point of human failure in the giddily vast architecture of American Armageddon was not just inconvenient. It might set off a chain reaction that could rupture the whole system. From the moment Major Hering spoke up his superiors knew this just wouldn't do.

In their effort to clamp the lid down tight the Air Force brass played a game familiar to any long-service member or dedicated sports fan of Permanent Washington: they took Hering’s question out of context. Hering’s actual question — can we guarantee a lawful order under UCMJ all the way to the top? — became a declaration of absolute dissent, a sign Hering would refuse to turn his key down there in hellfire’s cockpit any time he got a bit pernickety about the provenance of information coming his way. Pointedly and many times, Hering said no. He was Air Force all the way down; he would do his job past the outer limits of his devotion so long as it was a lawful, an American, job, as everything built into United States military law required it to be. The brass tacked again: Hering didn’t have a need to know, at his operational level, how such things got done. That got Hering’s back up a little. As an officer in whom was reposed special trust and confidence, like they said at every promotion ceremony, and as a human being about to do the most awe-filled and serious work the Air Force had on offer, Hering saw it as an American right to know that the system lived up to American standards. The light-blue machine prevaricated. Sure now that all this would come to no good, Hering backed off, decided to be a good airman, and put in for a transfer to other duty. But that would keep him in the system, somewhere, him and his inconvenient questions. So a few weeks on from the transfer request the brass scooped out the bad seed. Administrative discharge, they said. “Failure to demonstrate appropriate qualities of leadership,” they said.

Like hell, Hering said. He appealed the discharge to a Board of Inquiry. There it might have lain, one man’s voice against a verdict predetermined and an institution almost giddy with anxiety to pretend this had never happened. But strange things were abroad in the land. Hopped-up hatchet men for corrupt administrations blew up buildings and dropped the dime on presidents. Congress wrestled back imperial prerogatives from the larger-than-life Executive Branch. Towering vice-presidents beloved of American conservatism turned out to be cheap grifters not good enough not to get caught, then tumbled out of office in a week. A bunch of idealistic crusaders briefly grabbed the reins of the Democratic Party, that crazy-quilted big tent practically built on machine politics. Third parties marinated in racism and reaction monkey-wrenched elections to flex their muscle. Modest senators from the Great Plains who wanted civil rights and social democracy and reform of the big, clumsy, secretive state ended up in the Oval Office. And newsmen drank bottomless draughts of their own ambition to remake the national landscape with the next big scandal or prophetic cry for America to live up to its principles.

Thus, an administrative flunkie of the Board of Inquiry who thought Hering had gotten a raw deal talked to a local reporter. The local flack talked to a full-up correspondent, a guy who wrote long-form for the monthlies name of Rosenbaum, hunting like every other long-form habitue for the next diagnosis of America’s moral and societal crisis, the next hero or villain of the tale. Ron Rosenbaum cast his eye over Hering’s legal woes and saw not only a juicy earner for The Atlantic or Harper’s but a deeply necessary morality play about Cold War America, with a hero who asked the essential question about a broken system. Soon enough Rosenbaum got to talking over coffee to a senior staffer for an ambitious young Wisconsin congressman on House Armed Services. Then the staffer sat out for lunch on the Mall with Gene Pokorny. Then Pokorny thought about it, and talked to Frank Mankiewicz. At that point the stories of Major Harold Hering and President George Stanley McGovern bumped into each other.

For the president, who asked Ron Rosenbaum to the private presidential office just off the Oval, a little more like the professor’s digs George McGovern likely would’ve inhabited if the politics bug never bit, it seemed plain enough. Once he’d sat down with smiles and patient questions to get Rosenbaum to tell the story, it was only more so. McGovern looked at Major Hering, at his career, his logic, his impulse, his question, and McGovern saw himself. It was the very thing people had to do, that had to be done for the country, for someone to ask that question or a dozen others like it. So he sent Gary Hart’s deputy Doug Coulter — Coulter who’d seen the elephant himself by choice and sense of duty, in the long grass astride the Ho Chi Minh Trail, then come home to change the world that chose a war like that — to meet with Hering and Hering’s legal counsel in quiet. After an evening spent scrawling swiftly through a pair of yellow legal pads, deep in conversation with Eleanor, the president also pulled together his senior legal minds, Arch Cox the AG, Cy Vance himself at the Pentagon, Gary Hart, Ramsey Clark, Solicitor General John Doar, and so on. McGovern went to Tom Moorer too, the cherub-faced Alabaman admiral who chaired the Joint Chiefs, because McGovern expected this whole business would stir up the Air Force establishment nastier than a bed of hornets. But, so be it.

The first part of the solution was as precise and elegant as it was vast. Already a proposed constitutional amendment, heavy with much more detail than the typical model for such acts, had passed Congress out into the states that dealt with when, and how, and on what terms, a United States President could use military force in concert with Congress’s constitutional right to examine, debate, and pass final judgment on such acts. Folks had taken fast to calling it the War Powers Amendment for short. Now, there would be War Powers Amendments, plural. In what George McGovern called the greatest spate of constitutional reform since Woodrow Wilson was president, designed to make America’s holy writ fit and vital for the nuclear age, two more proposed amendments would go before Congress, then out for ratification if they passed.

The first, designed to deal with presidential succession in the event both an elected president and vice-president were rendered unable to serve, filled in gaps in the Twenty-Fifth Amendment on that score, turned back the clock on the 1948 Presidential Succession Act by returning emergency succession to the deeper bench of the Executive Branch and an older legal model of who counted as “Officers of the Government,” and promised timely nomination and special election of a new Vice President in such a crisis. The minds of plenty a congressional staffer or correspondent turned to the late unpleasantness over Brookingsgate, but as framed for consumption by the McGoverners, the amendment really was designed to right the ship of constitutional succession in the event of an attack on the United States of the kind a nuclear power might make.

The second, well, as George McGovern said with a smile that one was Major Hering all the way. Fired with the belief that Harold Hering’s inconvenient question was the best idea about war powers and the funhouse-mirror logic of the Cold War that McGovern had never thought of, this additional amendment hit that nail dead center. On the logic (that gladdened Birch Bayh’s heart among others when the language hit the Senate) that executive officials appointed through the advice and consent of the Senate could act as a functional extension of Congressional war powers, it required that a presidential launch order be confirmed as valid by an executive official who’d taken their job on senatorial consent, except in a specified case where communications were demonstrably devastated by armed attack or natural calamity such that confirmation couldn’t be asked and given. It required, too, that military personnel obey only confirmed orders at risk of court-martial, and punishments for presidents who tried to go around the process — the most we can do, counseled Cy Vance, but a necessary symbol at least.

A few congressional denizens of the hard right tied themselves in knots over a president giving away authority to shore up checks and balances, indeed a whole campaign was launched with head office down in South Carolina to argue McGovern’s move threatened the worth of the presidency itself. But when even folks like Barry Goldwater said, provided the “breakdown exception” held up, that this produced a more lawful system with less unchecked state power, the indigestion of a few Birchers and Boll Weevils didn’t get too much in the way.

This was, however, only one front in a broader war. It was older than the bright ideals of the new administration, and deeper. Three presidents had fought it already — the celebrity of Jack Kennedy, the grandiosity of Lyndon Johnson, and the ruthlessness of Dick Nixon — to no real effect. It had started in the unruly mid-Fifties muddle of American policy, or lack thereof, on nuclear weapons and the waging of nuclear war. In short order the most well-adapted and relentless beast in the armed services’ bureaucratic pastures, the Strategic Air Command, had vaulted forward into the lead. Both an Air Force command and a “specified command” with overarching purpose beyond one service, SAC had the advantages: in an age of jet bombers it controlled the great weight of American nuclear power, and was led by the Pentagon’s high priest of strategic bombing Curtis LeMay. Despite that, both outside consultants and the other services recoiled at the SAC model of clumsy excess designed mostly to justify vast, spiraling, upward growth in SAC’s overall scale and its political and bureaucratic leverage, and worked towards alternatives. Near the end of the Fifties that came to a head.

It was a fight, and a tale, made for myth, of deeply different and opposed philosophies about nuclear Armageddon, fronted by entirely different men. On one hand came the United States Navy, backed tacitly by the Army and Marine Corps, and the newest marvel of a technological age: nuclear-powered submarines that could load out and fire ballistic missiles. This new resource was seized upon by a man who understood its potential, the Chief of Naval Operations at the time, Adm. Arleigh Burke. A cool, pragmatic Swede from the Rockies, Burke was a surface-warfare man by vocation but also a grand strategist who understood the potential SSBNs had given him. Against him came the purest and most terrible expression of SAC’s flight into absurdity: LeMay’s successor at SAC, Gen. Thomas Power, a kill-the-bastards enthusiast who frankly unnerved many a powerful man inside the national-security loop, chuckling at plans to annihilate nations that were largely bystanders to Soviet-American conflict, off-kilter in his responses to others’ emotional cues, utterly dedicated to the SAC cause.

The seeming clusterfuck of disjointed, overlapping, and countervailing plans for hurling Armageddon at Moscow had got President Eisenhower’s ex-supreme-commander up. Ike wanted a single, unified, streamlined plan for the employment of nukes if it came to it. As the psychic costs of his heart attack rose while the days of his administration faded, Ike found himself chased too by the ghosts of this looming holocaust of physics and the desire in his words to “get it down to the deterrence.” To that Burke had a reply. SAC, so Burke said, was a funhouse mirror of nuclear policy, wildly distorted with excess resources, piling megaton after megaton onto programmed targets where people would already be dead, rooted in fleets of bombers highly vulnerable to a preemptive strike, on a hair trigger to throw every damn thing at all of the Commies all at once with no discretion nor process nor strategy. Instead, Burke argued, you could have a nuclear force based on just about four dozen SSBNs, effectively invulnerable to first strike, able to use or to withhold their weapons on the basis of reasoned policy at command level, aimed at the people and infrastructure of a nation — to deter in the classic sense — not down a money pit of building ever more nukes to chase the other guy’s nukes.

It had great appeal but, by the moment everyone in the armed services not tied to the Air Force rallied behind it, the Eisenhower White House had run out of bureaucratic time. In the end, they handed the whole thing over to SAC on the basis of institutional resources and past experience, and told them to get on with it. The result was SIOP: the Single Integrated Operational Plan. All but independent of civilian, or even the Joint Chiefs’, control it first targeted an almost comically vast swathe of “designated Ground Zeroes” in the Eastern Bloc, then proposed a management system to hurl all of America’s warheads at all those targets in a tremendous fury that critics called a “wargasm” for a reason. Russians, Chinese, satellite peoples, all would die in the fires of SIOP whether they were actually at war with the United States or not, because it was simpler that way and, being Commies, America would’ve gotten around to them eventually anyway. By Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee’s iron rule that people first make secret what they want to get away with, SAC walled the target selection and programming process off from scrutiny with special levels of security that might be interpreted to keep a sitting president from having a look at the printouts. Three administrations had chipped away at the fortress’ walls and tinkered round the edges, but SIOP still sat there supreme: with it SAC was all but a military within the military, and the Air Force supreme above its fellows with the biggest budget and greatest Cold War sway.

To this as one the McGoverners said, the hell with that. To make that more than sentiment took time, of course. McGovern himself, in this case, played a central part. That part hinged on the president’s relationship with his first Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Admiral Tom Moorer. Moorer was a conservative naval fighter jock from the Deep South, a Vietnam hawk, a SALT skeptic, ranged against any tilt to Israel based in part on the attack on the USS Liberty in ‘67, and a zealous advocate for larger defense budgets in Southeast Asia’s wake. But he was also an accomplished bureaucrat, methodical, well-considered enough in his own strategies to build a working relationship with the new chief executive, which Moorer believed would make the nation less vulnerable to change and dampen institutional effects of McGovern’s idealism and reforming zeal. Moorer also understood two other things. Despite McGovern’s disdain for policing the world and disgust with the enterprise in Southeast Asia, the commander in chief dealt with the uniforms squarely and with more professional respect than his recent predecessors. Also, McGovern was enough of a politician that he considered “that little eavesdropping business” when Moorer’s office had spied actively on the Nixon-Kissinger China opening both more serious and more useful as leverage than Democrats past. That tended to help McGovern and Moorer get to know each other, which was what the president wanted.

President McGovern knew something else, too: that Moorer belonged both to the generation and the faction of Navy men who had lined up behind Arleigh Burke in the great nuclear debates at the end of the Fifties Despite Moorer’s job as the vicar-on-earth for the whole uniformed military, the admiral carried the outcomes of that dogfight deep in his craw. McGovern expressed that he wanted to explore those issues from time to time and was able too. Things even reached the pass where the president invited old Arleigh himself, retired a decade or more, to a long afternoon’s coffee at the Residence, where the men could stretch their feet out on veranda chairs and beguile the hours about what Burke’s planners had called the “alternative undertaking” — just the kind of label to strike President McGovern’s fancy. Eyebrows flared in the Air Force firmament but by the same token they had begun to make an assumption common among government agencies that did not wish to be reformed by the “McGovern moment”: that in practice the administration was a mix of naive amateurs and closet moderates, who in the end would make a lot of noise but do little.

As Clark Clifford later observed, with his almost leering trademark grin, it was possible they’d got that one wrong. The first blow was especially well-struck. In an executive order, tucked away in the flurry of work after the Mideast warring of late ‘73, the president first countermanded, then by the end rescinded, the layers of security clearance SAC had piled on the national targeting process. This was indeed Ben Bradlee’s own advice to President McGovern — “George, this whole thing’s a pissing contest, and if you want to see how big their dicks really are you’ll have to pull their pants down” — because the president liked seeking out that sort of thing from the voluble editor from time to time, before the drinks got taller and the ghosts of Jack and Bobby came into it. It was an elegant solution — if SAC actually called the decision out they could either take up the case with Tom Moorer and three other armed services that wanted them cut down to size or try their luck with federal courts eager to show their bona fides against the arrogance of secret power.

The second, as Gary Hart sardonically observed, really stirred up the anthill. The administration wanted anyway, for other, complimentary reasons, to reform and restructure the military’s system of unified and specified commands. No sooner had the McGoverners thrown open the doors to SAC’s war rooms when they proposed an administrative solution to the inter-service politics that dogged SAC control of the Third World War-in-waiting. Deputy Secretary Tim Hoopes’ office proposed a United States Strategic Command, USSTRATCOM for short, that would put all three legs of the triad under one roof, Zoomers and Squids alike, together with North America’s integrated radar and air defense networks. Command of STRATCOM, they noted in plain, economic words in the last short paragraph of the proposal, would rotate between the Air Force and the Navy. And that lit the match off.

It was a flurry of elements. The Air Force’s vice-chief of staff, Dick Ellis, and the general eyed as the next CINCSAC, Russell Dougherty, both announced they would retire early rather than see through a transition to STRATCOM, a particularly prim form of protest. Not one to waste a shot at photogenic martyrdom, General Alexander Haig — noted adjutant of the Nixon crew, number two man in the Army though passed over for the top job after Abe Abrams smoked himself methodically into the hereafter in ‘73 — resigned with a laundry list of grievances passed swiftly around the circuit of backbench House Republicans who could insinuate these into Congressional Record. Distinguished alumni of the service summoned the durable segregationist gnome John McClellan, chair of Senate Appropriations, to gavel in his defense subcommittee and have at the security clearances of the administration and every comma John Holum ever inked. Mailing lists from groups that even the John Birch Society couldn’t see on their right-hand horizon cranked out newsletters about how Gary Hart’s youth in the Church of the Nazarene meant he was a secret disarmer, and that President McGovern had been recruited into the NKVD in Italy during the war. As the president said in a confab with his national security adviser Paul Warnke, it was all a hell of a tussle.

But the McGoverners knew they held the cards. In particular, that the little birds of the Pentagon eaves who whispered in Tom Moorer’s ear knew the present CINCSAC — a highly-decorated fighter ace and decent fellow by the standard, Gen. John Meyer — had heart trouble and would retire soon. If the administration could grease the correct congressional palms and time statutory reforms of the commands just right, Meyer would have time to run STRATCOM just a little before the strange bedfellows in the West Wing and the Joint Staff could bring a Navy man in.

Which they did. Not just any, either. The president reached out to Hawaii and requested the presence of the Commander in Chief, United States Pacific Command, in D.C. for a conference. Admiral Noel Gayler — “that’s GUY-ler,” he told earnest, sideburned young West Wing staffers who steered him to the Oval — was a man the McGoverners would have had to invent otherwise. Tall for a pilot, lean, and lion-in-winter handsome, Gayler hailed from Alabama like Tom Moorer but Gayler’s politics, and perspective, were quite different. Gayler was a talented carrier jock, who’d won no less than three Navy Crosses in about six months out in the South Pacific during the war, then risen to command aircraft carriers and lately PACOM. But his career was defined by another track as well, and a secret cause. More than almost any other Navy man, since 1945 Gayler had been involved deeply and repeatedly in the development of America’s nuclear arsenal, its technology, its administration, its strategy. He had watched the Devil’s own furnaces rise above Eniwetok, walked the islands with the geiger-counter boys, worked in the Navy’s own offices for atmoic war, even become one of the token Navy boys among SAC’s Templars on the nuclear targeting board itself.

Gayler stood at the opposite end of the world from Curtis LeMay or Tom Power: Gayler believed nuclear weapons were an obscenity, an active, aggressive, and almost irresistible threat to the future of humanity, a sin that had slowly and methodically to be expunged. But he was no radical, and he knew how to plan. Rather than wave signs or shout at buildings into the wind, Gayler learned the trade, better than almost anyone, worked his way up, not only stayed in the game but reached its heights so there always would be at least his voice of reason. And he did not expect, now, to beat W53s or Polaris SLBMs into plowshares. But, sat down with this trim and earnest president, who had warned since his college graduation against the path “from cave to cave” — from Stone Age to humanity’s nuclear eclipse — there was nonetheless some work Gayler could be getting on with.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

It came around the time the McGovern administration first got its work boots on. In his wood-paneled Senate office Barry Goldwater tidied up staffers’ drafts of speeches he’d hurl like bolts at the new crowd in the West Wing, about sacrificing American jobs and childish radicalism that would strip national security bare. Jules Witcover warmed up some rare friendly column inches (you declared peace now and then, it confused the enemy) about how on defense the McGoverners were principled reformers who’d stand athwart General Dynamics shouting “Stop!” Deep in the scrum, Paul Warnke pulled young John Holum aside from a staff meeting.

Cy Vance, returned to his Sixties roost at the Pentagon and now in charge of the whole damned department, had given what amounted to an orientation for senior civilian staff new to the remorseless jungle of the “E Ring” where senior uniformed and civil personnel kept offices. Don’t get snared in details, said the rumbling persuasion of Paul Warnke to Holum. Don’t get caught up in systems either. The Chiefs — the uniformed leadership of the armed services — will tie everything up in systems. That’s where the money is and from their point of view that’s where the sweat equity is in the bureaucracy. Don’t get caught up. Now Warnke settled into the Churchillian scowl he liked to use for effect and said: processes and people, John. That’s where the action is if you want to get something done. Don’t live or die on systems; it’s processes and people.

Warnke by and large had his head on straight. Secretary Vance felt much the same: both men had done their time under McNamara, the giant with feet of clay, had seen what it looked like when you put too many eggs in a basket or failed to speak up when either the White House or the services made bad — bad? Catastrophic — decisions. They knew too the deep tapestry woven in iron cables between senior military leadership, long-service congressmen, and favored corporate lobbies in the defense sector. You could fight for years for or against a grand strategy or a missile or a bomber or a ship, but if you didn’t change the mechanisms, affect the rules, it didn’t really matter much at all. So they did.

Processes took a pincer movement. Enabling statutes were the highways and byways of DoD: they put you in a lane and described where you could go from there. So in the closest thing the young administration had to a honeymoon with a Congress quite leery of letting the sun shine in, Cy Vance went to the committee chairs with dour but oddly soothing brahmin mien to tell them the McGovern administration wanted to restructure the Pentagon. After the long befuddling messes of the Southeast Asia years, Vance reckoned that an actual push for efficiencies and streamlining not only stood a chance but might buy a little goodwill before young Holum or some of the West Wingers got too gleeful about closing Navy Yards or turning mothballed tanks into razor blades. Vance was right enough that he got to move the ball down field.

The McGovern crew moved to sort the subdivisions and internal departments of the Pentagon into two sets of commonalities. In one batch they placed what Vance described, with elegant economy, as “tasks in common,” needs or functions performed in the interest of all the several uniformed services. Stewardship of those tasks would go to four newly-minted Under Secretaries: the Under Secretaries for Policy, for Intelligence, for Operations and Procurement, and for Reserve Affairs, the last of them responsible for joint coordination and regulatory oversight for the services’ National Guard and also Reserve elements.

Down a very different stovepipe went the services themselves. There, a much larger and more activist role was settled on the Deputy Secretary. He would act as everyday supervisor, coordinator, judge, and referee for the service departments and the service Secretaries of Army, Navy, and Air Force. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs would take on a dual and interlocutory role, as the DepSec’s military deputy for coordination of the services, and as the services’ uniformed spokesman — much as the Secretary was the senior and civil one — for the armed services to the National Security Council. This bunched the department under two big tents and “flattened,” in the bureaucrat’s argot, relationships between administrators and everyday business so the Under and Deputy Secretaries could mind their own houses without too much confusion between them and the action.

Reform of the unified and specified commands system fell in with the same train of logic. With bucking-up memos from both Paul Warnke and the president’s own desk, Secretary Vance set up the deftly named Hoopes Commission so that Vance’s deputy Tim Hoopes could shepherd and tend this overhaul. The commission report issued in the waning weeks of 1973 slashed the number of unified and specified commands from ten (some said it was really more like twelve, a couple of outfits canned in the Sixties still had substantial ghosts in the bureaucratic signal) down to five, of which STRATCOM was only one piece of the process, if a foundation stone. Hoopes also lent a practiced editorial eye to the legislation and federal regulations that shaped the relationships of the new commands to the standing services because differences of vision and opinion between the “Sinks” — the CINCs, commanders-in-chief of the unified and specified outfits — and service chiefs often led to conflicts that rubbed each of those two layers of career military perspective the wrong way.

Restless ambition for more grand redrafting reached out from “the building” into that very military-industrial complex Ike had warned about. Ken Galbraith at Treasury figured the hand that held the public purse could probably handle a whip, too, and saw the tangled landscape of defense contractors and sub-contractors and sub-sub-contractors as ripe for consolidation, maybe even a new public corporation or two. Cy Vance endorsed the spirit of Galbraith’s schemes though not always the letter, especially when it meant running up against the fierce energy of congressional grift. Likewise Vance saw the sheer bad press of “reconversion” coming, taking his time before offering alternate methods of selling the same thing while the administration took its lumps across the street in the Capitol and in the merciless jackhammer tutting of the press.

A few small, bold experiments worked especially in electronics, where there was a burgeoning, oncoming civilian sector to lift boats. But otherwise one of the fondest hopes of the McGovern-adjacent, that like the United States economy in 1945 a landscape of surplus military-industrial plant could be magicked into engines of civilian prosperity, mostly turned into a lightning rod for bad press, bad blood with the unions, and attacks on “reckless spending” for reconversion from senatorial Boll Weevils.

Boats, rather than lifting, really were the biggest problem. The shipbuilding sector ran scared from the massive tonnage of Japanese and now South Korean output; while a few members of the president’s Keynesian conclave didn’t mind quotas, the Treasury worried about pissing off Tokyo on regularized foreign exchange flows, while the shipyard unions set the wire-service jackals on the West Wing practically for sport. In one memo among the steady throughput from the Secretary’s office over to the Resolute desk Cy Vance wondered drily about the irony of Ivy League econometricians worried about the false consciousness of shipyard welders who’d gotten a nice mortgage and a shot a putting the kids through college out of building destroyers.

Vance, among others but Vance especially, pointed out there were other angles on which you could come at costs. The administration mobilized the moment — or more often tagged along with it nudging now and then — and got the congressional reformers on the job. In his senate days President McGovern had trucked quite a bit of the Members of Congress for Peace Through Law, a bipartisan caucus rooted in hacking at the brambles of Southeast Asia root and branch that grew into the main talking shop for liberal reformers who wanted to pare back overzealous defense procurement while they showed credible technical expertise. Thrilled to have a fellow-traveler in the White House, the Members for Peace Through Law put their backs into it. Early in 1974 their marquee bill turned into the Defense Procurement Rationalization Act, more often the Aspin-Hatfield Act in the Annotated United States Code, in honor of the bespectacled, pernickety technocrat Les Aspin in the House and McGovern’s liberal-Republican chum the philosophical, movie-handsome Mark Hatfield in the Senate.

Aspin-Hatfield laid out a new, systematic calendar and metrics for the defense-procurement cycle and if it worked right would stem whole, flailing projects before they outstayed and overgrew. It dovetailed with a process begun already by the McGovern administration. In the first year of a president’s four-year term, any given administration was now required to hold and complete a Quadrennial Defense Review, a QDR in the acronymic argot of “the building.” This would no longer be two hundred pages of throat clearing with tidbits thrown in that an administration could play four or five different ways with congressmen and defense-contracting campaign bagmen. Now QDRs would have to lay out concrete proposals and metrics for force structures and systems procurement. The procurement requirements would turn into requests-for-proposals with standards for deadlines and cost estimates.

For projects that met certain standards of relative simplicity, the RFP window was set for two years, for other projects four; blue-sky projects would have to submit substantive technical requirements and proposals for how to meet them inside the deadline of a four-year administration. If vendors failed to meet the window deadline on RFPs or the DoD found it necessary substantively to revise requirements, they’d can the whole process and punch the restart button after another QDR. If RFPs went as planned, that would start another cycle, either two years or four, to put the widget, gadget, vehicle, or other item into low-rate initial production. There were byzantine systems for appeal, but Aspin-Hatfield built those stairs steep and twisty to make sure most failing projects fell off them. The intent was simple but powerful: keep DoD from shifting the goalposts and reinventing wheels just so project managers could get their management tickets punched; keep contractors from leading “the building” on with promises of jam tomorrow that always turned out, again, to be tomorrow not today; stop throwing good money after bad when a development cycle went south.

Because it really was all about one’s point of view, as Ken Galbraith conceded at least once when Paul Warnke poked at him about it, the administration found more willing partners for industrial consolidation and downscaling on defense when that got dressed up pretty enough for the Wall Street Journal as mergers and acquisitions. To the great satisfaction of Missouri’s almost-full house of Democratic governor, senators, and representatives, the administration laid open a path for surging McDonnell Douglas to absorb Martin Marietta, still stumbling through a thicket of bad press after the famous sex-discrimination suit that harpooned Martin Marietta’s personnel office. The newly refashioned and expanded military-industrial operation at McDonnell Douglas now became an offspring subsidiary dubbed McDonnell Douglas Martin. In a grand Galbraithian kitbash that took three years of to-ing and fro-ing in memos, the McGovern Pentagon midwifed Litton Naval Shipbuilding, which brought together Ingalls, Newport News Shipbuilding, plus Newport Drydock & Design’s submarine operations. As the McGoverners fondly hoped this raised up a challenger for contracts in the form of Bath National, a marriage of New England titans Bath Iron Works and the Left Coast’s NASSCO.

At other times, consolidation ended up in the cross-hairs of crossed purposes. During the fly-off for the Air Force’s A-X project Les Thurow at OMB fired off a memo to Vance and Tim Hoopes, cosigned by Ken Galbraith, suggesting that DoD pick Northrop’s YA-9 aircraft for the contract to push the other competitor, Fairchild Republic, out of the business and consolidate more aircraft-building at Northrop. Hoopes, backed both graciously and strategically by Jim Gavin at Commerce and Industry, answered back that there were two issues with this clean-line logic. The first was that Fairchild Republic’s YA-10 was a better aircraft overall, and if the administration wanted to cut through the fog of Nixonian and Wallace-like innuendo that socked in the news services they’d need facts for the job. The second issue was that a YA-10 production line would run in some of the most heavily Democratic House districts in the country, to the benefit of relations with several powerful members.

More often, again, the Pentagon could move more pieces on the board with the hand of friendship. In 1974, with frankly elaborate secrecy as Cy Vance noted when the meeting took place, senior Chrysler executives sat down with the Secretary of Defense to tell Vance Chrysler meant to flog its large, crucial defense and space divisions on the open market so as to raise fast cash for Chrysler’s failing, automotive core. Vance sat down with some usual suspects, calculated to get the economists’ conclave over in the West Wing to buy in, then broke out his appointment book to start scheduling Federal Trade Commissioners and members of Senate Commerce. In the course of the next sixteen months Chrysler’s space-program assets were sold to North American Rockwell’s subsidiary Rocketdyne.

In the same span, to the particular satisfaction of the Treasury Department, Chrysler Defense’s large land-systems assets and physical plant were spun off from the parent company, while in tandem the government encouraged General Motors to sell off its defense assets notably the Cadillac Gage vehicles division. These parts from two of Detroit’s Big Three were fused together in a new corporation, simply enough called Detroit Defense. For its first boss, when George Romney had passed beyond the bureaucratic veil after all he could do for the nation’s integration at HUD, Vice President Hart got on the phone with Romney and said that as one Michigander to another it’d be a great good thing if Romney could step back into the corporate world and run the Motor City’s newest defense contractor. It was, President McGovern remarked to Secretary Vance, not at all a bad look on the old boy.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

There were fights and friendships and committees and tantrums and congressional hearings and long, subtle games of bureaucratic chess over platforms too. The president’s chief original national-security guy John Holum, now setting his stamp on the Undersecretariat for Policy, was not only a well-versed and polymath skeptic but also the Capitol Hill reformers’ inside man. In particular, Holum dismissed what he saw as the baroquely technological approaches favored by the permanent-Pentagon elites and embodied in aircraft like the F-14 and F-15. Holum, like one of his friendliest ears in the Senate the fiscal witchfinder Bill Proxmire, was deep enough in the tank for the countervailing Light Weight Fighter demonstration down-select that like Proxmire, memorably described by Frank Mankiewicz as “moved often by the pillar of rectitude up his ass,” that the promising young Under Secretary had grown gills.

Plans to ring the gong of reform and hail a new day by shitcanning the F-15, of course, survived not even one afternoon under Stewart Symington’s seraphim glare. The senior senator from Missouri, a former Secretary of the Air Force in his youth, made bright and clear to a freshly-inaugurated President McGovern that it would be a very cold day in Hell indeed when St. Louis’ biggest new industrial project, the pride of old McDonnell Aircraft who made the F-4 Phantom, would disappear leaving a gaping wound in Missouri’s economy on the prim say-so of an ambitious deputy. That went for Symington’s junior partner Tom Eagleton too, former district attorney of that very city. Since the little birds that whispered in Frank Mankiewicz’s ear (or often Gene Pokorny’s or Doug Coulter’s, who then whispered it in Mankiewicz’s) said the “boyish” Eagleton was responsible for that whole “amnesty, abortion, and acid” dig during the ‘72 cycle, they preferred him in the president’s favored position, pissing outward from the tent instead of letting fly inside. Besides, President McGovern had learned his trade in the legislative branch; it was a shame on the principle of the thing not to be able to kill more big, gold-plated projects, but they needed Symington on about a hundred and one other pieces of legislation, and when it came to budget cuts there was more than one way to skin a cat.

There was plenty of friction with the Air Force already, even if you left SAC out of it, summed up by the fact that more often than not the uniforms and the civilians each wanted to invest in things the other did not. Tim Hoopes set out a tart compromise with the service, that he Air Force could have exactly as many combat wings of F-15s as it could actually pay for, which had the advantage that it helped the administration reduce the number of tactical aircraft wings as it desired to do as a matter of course. At the same time the McGovern crew had a couple of systems they actually wanted to buy, much to the service’s chagrin. One was the Fairchild Republic A-10 — and the A-X project generally, that even John Holum saw as a sensible piece of inter-service coordination for a straightforward machine that would do something useful on an actual Central European battlefield in terms of close-air support. The other, after a fly-off with McDonnell Douglas’ competing project the YC-15, was the Boeing YC-14 which would enter service as the C-14A Trojan despite the light-blue uniforms gladhanding as many congressional friends as they could to throw up roadblocks. The C-14, with its “Coânda Effect” overwing engines that produced dramatically short takeoffs and bleeding-edge maneuvers from the doughty little transport, would be a jet-powered successor to the ubiquitous C-130 in regular-service squadrons, with the Hercs shifted to the Guard and Reserve.

The Light Wing Fighter fly-off went ahead too, under different auspices though John Holum still hoped against hope they could stake the F-15 in low-rate production if an LWF exceeded its metrics. Several key NATO allies sought a quick successor to their widow-making F-104s and hoped an LWF winner would do. There were even potential contracts out there for a loser that flew well. The McGovern administration, meanwhile walked a fine line here in support of the Nixon Doctrine, what Paul Warnke had called “the pearl among the swine” of Nixon administration foreign and defense policy. The earnest, hopeful McGoverners worked hard to stem arms sales to the world’s conflict zones and the Third World more broadly. At the same time, they saw no reason American companies should not vie to make a buck helping established allies defend themselves with less US outlay.

Thus the LWF contenders flew, and the NATO partners — Belgium, the Netherlands, Norway, and Denmark — picked General Dynamics’ YF-16, which would be license-assembled abroad by Fokker and Belgium’s SABCA in partnership with General Dynamics’ big Texas plant. It was not the only success for GD or indeed for Texas: as the reformers hoped it might outflank the F-14 at sea, and for the legislative favors of a clutch of powerful Texan Democrats in the House of Representatives, the administration put its thumb on the scales for the Vought 1600, a joint venture with General Dynamics that would enter service classified as the “F-16N,” as the Navy’s own lighter-weight combat jet. In time the administration even held its nose in exchange for firm votes on the Revenue Reform Act and approved limited production of an F-16A expressly for the Guard and Reserve, to replace aging, early-model F-4 Phantoms and F-105s, so that in their enlarged role with respect to NATO Guard squadrons of F-16s and F-4Es would be “ready the first day” for a fight at lower logistical and procedural costs than active squadrons. Northrop was hardly left in the dust — their F-17 Cobra might have lost the fly-off but with a new generation of General Electric engines it sold on the same license-assembly principle to the Australians, Canada, France’s Marine Nationale (where it replaced their older F-8 Crusaders and preempted an improved Etendard jet), to the Luftwaffe, the Italians, in time democratizing Spain as well.

No conventional weapons system, however, was quite the political football that aircraft carriers were. The administration entered office determined to trim their sales: the most devoted reformers saw them as easy targets for massed sorties of Soviet submarines and missile-laden bombers, and otherwise too much the gunboats of Cold War diplomacy for comfort. Indeed the sharpest negotiating position, the Alternate Defense Posture of January ‘72, wanted their numbers dropped to six. This the Navy would not stand; on one hand they had some arguments from fact that the most modern carriers were sturdier even against nuclear-tipped torpedoes and missiles than the reformers presumed, but on the other they were also key to convoy protection and power projection in non-nuclear conflict. The administration moved swiftly past the cease-fire in Southeast Asia to cashier the smaller Essex-class carriers and draw up a case to mothball the older Forrestal-class, in no small part because they could see the admirals coming, chatting their way through Capitol hallways with the armed-services committees.

Even before John Stennis narrowed his bespectacled eyes the navalists had an in, or maybe two. One was that the president himself had imposed a “floor” already on the alternate-posture proposals: the Navy should still be able to deploy a pair of carriers regularly to the Mediterranean, which McGovern saw in terms of a military backstop for Israel. Once the war of Yom Kippur had played out the admirals, better perhaps at dancing across the game board of Bureaucracy than their flyboy counterparts, argued that there should be balance between the Atlantic and Pacific carrier fleets for two reasons. The first was that, given the major reductions in force for US military assets in the Pacific imposed by the new administration, carriers were flexible tools both to project and to withhold power that lacked many of the costs of, say, Air Force wings in the Philippines or Army divisions in South Korea. Also, said the admirals to such West Wingers as they knew traveled close by President McGovern on his support for Israel, another carrier available in the Pacific, especially a nuclear-powered one, could back-door its way quite nicely to the northern Indian Ocean, off the Arabian Peninsula, in the event of more trouble in the Middle East, and again cost less than land basing. This way the Department of the Navy budged the reformers’ “floor” on carriers up from six to eight.

The other in was to play on something that the whole administration, from its wan pragmatists to its most zealous agents of change, wanted more of: anti-submarine capability. The McGovern appointees saw the Soviet sub fleet as the core and the engine of Moscow’s naval power, the clearest threat to American reinforcement of any battlefront in conflict with the Soviet Union. Indeed the intelligence community had reports, debated back and forth between the uniforms and the reformers, of a new class of very-high-speed Soviet attack subs, designed said the admirals to hunt and kill both carriers and American ballistic-missile submarines. The administration’s first Chief of Naval Operations, Elmo Zumwalt, met the administration’s focus on submarines with a pitch for his pet fleet design. Zumwalt, a charismatic, pugnacious figure of boundless energy who was also mildly liberal for a military man, made some personal friends in “the building” and more so in the West Wing. His pitch was the “hi-lo mix,” already implied in the McGoverners’ vision for the Air Force, with a core of ships of both high quality and high expense, and then sea lanes flooded with cheap frigates and missile boats along with a greater volume of US submarines.

To the last of these the administration was already agreed: a decision written into CART to hold off on a new class of ballistic-missile subs meant more slots available in congressional budgets for the Los Angeles-class attack subs, against whose early construction woes the waspish Secretary of the Navy Otis Pike had already set himself. Like the A-10 this was a rare place where even the Holums of the administration wanted more not less. On the high end, the administration embraced not a flood of gimcrack frigates kitbashed on the fly but a larger than planned order of the strong, spacious Spruance-class sub-hunting destroyers, which had plenty of hull and hangar space for new technologies to meet the threat. (Zumwalt also got some of his hydrofoil missile launchers; as they were built in Tacoma and cost not much at all they were cheap and ready leverage, alongside Boeing’s C-14 and nuclear cruise missiles, for votes from Warren Magnuson in the Senate and in rare moments even Scoop Jackson himself.) Zumwalt proposed another idea also, what he called a Sea Control Ship not much bigger than a cruiser but made to carry sub-killing helicopters and a few vertical-takeoff jets like the British Harrier for top cover.

Both the Navy and the administration agreed to make studies of the SCS; what may have mattered more was that, along with their voluble sponsor, President McGovern’s chief of staff Gary Hart fell in love with them. Resolved to prove to Permanent Washington that he was a serious man of bold ideas, Hart hitched his wagon to the SCS to set himself up as a gadfly to the defense reformers and soothe senatorial nerves about sharp defense cuts elsewhere. But as he sometimes did Hart had grabbed hold of the next big thing just as the central players left it on the vine to wither. By the time Zumwalt had authorization for feasibility and cost projections the clock on his tenure had begun to wind down. Indeed both the Vances and Hoopeses of the process and the other admirals alike had moved swiftly to assess the SCS precisely because no one but Elmo and Gary loved them, and their foes needed to look busy as the design died. Its bones, though, were grist for the ingenuity of Zumwalt’s successor James Holloway, who advanced on the whole deal from a higher plane of skill.

Holloway was, in short, most of what the enterprising innovator Zumwalt was not. Zumwalt had brains and popularity in the fleet and a lively mind, but a brash touch with a tendency to nag that meant most of his projects fell short. Holloway on the other hand was the son of an admiral and Navy all the way down, an easy and popular guy, who hid behind the glad hands and quiet smile a sharp political mind. He understood the McGoverners and, rather than recoil or reject, decided to use that sensibility to get what he wanted done. To the admirals he said, trust me, we’ll get there, and because he was Jim Holloway they did. With the civilians he got what he wanted by giving them what they needed.

All right, said Holloway, always one to ease into it. All right. We’ll stop the fight; here’s what I propose. The service will accept the administration’s target of eight big-deck carriers, four on the East Coast and four on the West, and we’ll keep our smiles on and our mouths shut. As the first Nimitz-class ships come on line in this decade that will eliminate all the aging Forrestals: in the corners of his own mind, and in quiet asides to the four-stars, Holloway called this a victory because in a few years the Forrestals would’ve needed expensive refits to stay in service, and why do that when you can plead poverty to a friendlier administration after 1976 that gets you more new ships? Also — here Holloway knew just when to grin at Gary Hart in his audiences at the West Wing — let’s not knock ol’ Elmo too hard about the SCS. The logic was sound, there’s a real need for comprehensive ASW platforms. But we can have them the McGovern way.

This was where the short, doughty Holloway would sit back in his chair and move all the pieces on the board in the air between himself and his audience. The administration has made substantive cuts in the regular-service Marine Corps, which means what’s left needs to be as ready and effective as possible. Also, it is never going to hurt for an administration of cutters and tinkerers and strategists and gadflies to keep someone as powerful as old John Stennis at Senate Armed Services in the good books, or rather keep the White House in his. So. If the administration suggests that Congress approve funds to build all six of the big new Tarawa-class amphibious assault ships, built by Ingalls in Stennis’ very own Mississippi, not only will that look good to the Marine Corps’ friends in Congress and the press, it will soothe John Stennis’ mind. They will also do the jobs of two or three smaller, older amphibious ships apiece at better through-life costs. Nice start, yes? We’re agreed on that?

Very good, Holloway went on. Now at the same time, we should remember that those Iwo Jima-class Landing Platform, Helicopter ships the Tarawas will replace aren’t done yet, not in terms of hull life. They’re still good ships for their size, we can get a lot out of them. And we’ve just had USS Guam out to sea rigged up as an SCS to test proof of concept on Elmo’s idea. If that’s so, why don’t we use what we’ve got to do a job without reinventing the wheel? For sea-control purposes the Iwos match speed well with our likely convoy ships, they’re nice big hulls with a decent hangar deck too. With a little tinkering — it was all in the choice of words, really, everything in Washington was about the right words — they’d be fine “sea control ships” by another name. The Marines already fly Harriers, they can spare a few to do top cover on these ships, and we have plenty of sub-hunting helicopters in service and when new ones come along they can fit right in. In fact, if you took some of those Canadian Dynaverts that the Corps and some folks in the administration, from what I hear, want to buy, you could slap a radome on them very nicely and use them for basic airborne early warning on the convoys. What you’ve got there is a very nice way to use our present inventory and make everybody happy. Sensible. Cost-efficient. Pragmatic. Practical.

With his light political touch, and the fierce energy of Gary Hart’s desire to one-up the Hoopeses and Holums, Holloway held on and won the day on his proposal. The Five-Year Defense Plan for Fiscal Year 1975 — the Pentagon’s annual exercise in looking downfield to telegraph their intent for the edification of Congress — had in it language for converting six Iwos to the sea-control role as the first Tarawa-class ships moved into sea trials and then active service over the following five to six years. In the same motion Holloway banked not only goodwill with the present administration but an entreaty to the next, whatever Republican the Bicentennial primaries coughed up, who Holloway and every right-thinking senior uniform assumed would sweep aside this winsome little experiment. Already Holloway’s secretaries were at work on numbers for what it would take to accelerate production of Nimitzes to push big-deck numbers up again what with the Forrestals safely in mothballs on the whim, it would seem to the Republicans, of the hippie-lovers in the West Wing. Given time, strategy, and patience, that could mean greater fleet numbers overall with “supercarriers” and sea-control Iwos combined. Holloway’s approach was practically Zen: you had to embrace the McGoverners in order to outmaneuver them.

Such room was hard pressed for the gold-braided professionals, especially in the full flush of the McGovern presidency’s first Congress. Fresh from the Southeast Asian debacle and at least a dozen major procurement projects from the Sixties on that had spiraled over-budget, crashed to earth, or both, the leverage of the services was close on a low ebb. Some officers were philosophical about it, content to make the ground ready, lie fallow, and wait for a new wind to blow in — from Washington state, perhaps? Or Arizona — Senator Goldwater seemed to have found his full, sharp, ringing voice again railing against the cuts to the Air Force and its bomber fleet in particular. Others succumbed to gloom. Still more did what you did inside the machinery which was to drag low and firm to slow down changes you disliked and work the congressional refs on appropriations. This did not always work: Air Force and Navy four-stars found themselves called on the carpet even by conservative senators for vague or over-ambitious project estimates, for failing to instill enough military discipline in the ranks, even for the opposite sin of stifling young talent under rules and make-work.

Networks for liberal reform, across parties and in both houses of Congress, also held the whip hand in this period. Several pet projects of the services were curtailed or derailed, or saved only when the uniforms compromised with the McGovern administration to save a given appropriations line in exchange for cuts elsewhere. Spurred by the Members of Congress for Peace Through Law, and backroom coordination with the administration through Tim Hoopes and Gary Hart, McGovernite forces rallied the House behind the Senate’s Humphrey-Cranston Amendment to the Fiscal Year 1974 defense budget that called for a reduction of 125,000 American service personnel overseas by the end of 1974’s calendar year. That ratified especially the White House’s massive cuts to US forces in South Korea, together with trimming in Japan and on Okinawa, along with substantial drawdowns in Europe. Indeed the West Wing’s number crunchers conferred with Secretary Vance and the Undersecretariat for Policy and came out for an additional twenty thousand in reductions for US forces in Europe, in line with numbers the administration had sought back when it was just a passing fancy of American liberals rather than the executive arm of government. For senior officers who wanted first to retrench and then grow again against a Soviet threat in the wake of Vietnam, the Ninety-Third Congress was a hard and chastening time.

That didn’t mean the administration had abandoned a view to the future, or to longer-term military growth. Determined to show their very different vision for national security policy had sound principles, the McGoverners delved even further into the details of procurement strategy and technical development, keen to promote a technocratic if detente-driven pragmatism. In the second half of 1974, spurred by the momentum of the Rambouillet talks, the senior administrators at the Pentagon sat down with the staff of the Joint Chiefs to examine strategic weapons policy and development in light both of CART and a future state of affairs in the 1980s simply labeled “after CART.” The great winnowing lay with tactical systems, as several dozen proposals for new nuclear artillery shells, or depth charges, or anti-aircraft missiles, or the like fell by the wayside. It was not all scythes and the death of budgets: the administration wanted to pursue further development of the B61 “family” of nuclear gravity bombs, with its “dial a yield” flexibility (multiple fuzings for different explosive yields) and role in the Pentagon’s Nuclear Sharing program with NATO allies, along with a fast track for the Pershing II missile with its longer range, far greater accuracy, and absence of warhead overkill compared to the older Pershing Is still in the field.

At the strategic level, the administration found its wish to set aside the fixed demands of the services laid on the table when President McGovern took office was rescued by events. The McGoverners at the top of the Pentagon burned considerable political capital to delay significant studies or lead-in expenses on major strategic programs in the autumn of 1973, in part to carry on their broad general review of major DoD expenses, also to buy time for the CART concept to take hold. By the next summer Cy Vance and faithful staff were busy with explorations of the manpower and conventional budgets to find room for strategic budgets, with a few stalwarts like John Holum fighting rear-guard actions on the nature of US nuclear strategy itself. Then Rambouillet caught fire and the administration had its room to move. When they did, they moved back, past the fixed ideas of the four-stars and the Nixon administration to the last Democrats in office and the font of Seventies nuclear plans, Robert McNamara’s STRAT-X study.

The outcome, as the DoD principals reread STRAT-X and explored more of its blue sky proposals (which included chucking a live Minuteman ICBM out the back of a big C-5 transport jet the second year of President McGovern’s term just to say it could be done), should have surprised no one who knew the men and minds involved. It came to equal measures caution, pragmatism, and a desire to really do more with less. In line with the great constrictions laid on the Air Force, the suits vetoed the service’s desire to go chasing after a direct answer to the SS-18 “Satan” with their “M-X” large missile proposal. The veto, drafted in large part by John Holum himself, was a masterpiece of pernickety care citing built in issues with design delays, looming cost overruns, and the failure to provide a basing model that could be paid for and made timely to work. Instead Secretary Vance signed off on using CART’s opening for development of a single new replacement ICBM on another theme from STRAT-X: a lean, smaller missile with the range of the Minuteman series and a more powerful warhead than the ones mounted on MIRVed Minuteman IIIs, fired from a road-mobile launcher. In theory a smaller number of those more survivable missiles, ever on the move, could help mitigate the “counter-force” threat of the feared and hated SS-18s.

For the Navy, in part with Secretary Otis Pike’s support as he laid into Electric Boat about shoddy work on the first few Los Angeles-class attack submarines, the theme was newer but slower. CART settled the medium-term shape of naval deterrence on existing “boomers,” and on the Poseidon missile, now with more range carrying a slightly lighter-than-full payload under CART terms. Eager for economies Secretary Vance nixed the proposed “improved Poseidon” in favor of working faster towards a much larger new SLBM to be deployed early in the 1980s aboard a new class of twelve submarines that would carry them. (In an ecological twist, the McGoverners chose to designate and name the future boats after America’s great rivers, as the Columbia-class.) In a stopped-clock moment the grey heads and gold braids of both Air Force and Navy had issued joint reports suggesting commonalities between that project and any new ICBM. The McGovern appointees nipped this in the bud, remembering the debacle of “something for everyone” in the Sixties with the TFX project that nearly killed the F-111 by using it as a platform for too many jobs. The Air Force would get their light, mobile ICBM, the Navy a new missile that would help the administration shift the triad’s center of gravity to the “silent service,” and everyone could probably get their systems on time with less hassle from Congress.

That left the flyboys. The deep cuts in SAC’s bomber fleet — though tied to new long-range cruise missiles that would keep late production B-52s useful for some years yet — together with the rise of STRATCOM, revisions of SIOP, and trimming the hedges of of the ICBM fields, all ringed the most powerful Cold War service round and tightened over time. And the bomber mafia’s pet project, now Rockwell’s B-1A aircraft, had progressed in Congress just about like a passel of angry cats in a sack. It had taken fifteen years and graveyards of other projects to get to a new bomber in the first place, and to be fair Rockwell had shown some technological flair. With adjustable titanium nozzles on the heat intakes, special paint and contouring, and electronic-warfare gear almost a generation ahead of most aircraft, the three hulking prototypes Congress bought and paid for looked like gunmetal condors painted in white flashing, bigger than football fields but with a radar signature roughly a quarter the size of a Phantom jet’s and supersonic “dash” just a few dozen feet off the ground. But brilliance cost painfully vast hoards of cash in a straitened age, and on one side you had flight-suited four-stars who passed talking points to strident hacks on the wire services that America would lose a leg of the triad without this, on the other puritanically correct senators battling for reason calling them dangerous white elephants that did nothing new when the nation needed tight budgets to kill inflation.