What's the only thing better than a New World? New Words, of course!

Introducing...

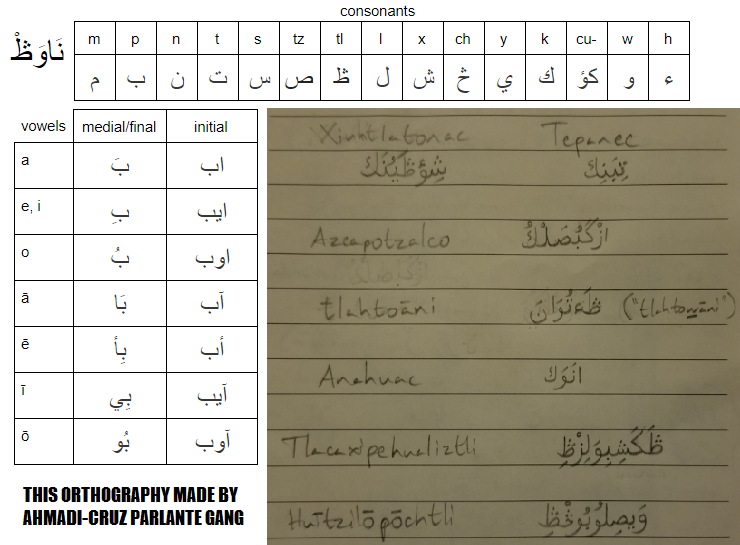

The 100% Halal Sufi-Approved Nahuatl Ajami [translator's note: Arabic based script for non-Arabic language]!

Some notes on the system:

Introducing...

The 100% Halal Sufi-Approved Nahuatl Ajami [translator's note: Arabic based script for non-Arabic language]!

Some notes on the system:

- Nahuatl's the easiest (major, well-attested) Mesoamerican language to make an Ajami script for-- not a lot of vowels or consonants. The real nightmares would be Yucatec Maya or Otomi's umlaut-vowels. And K'iche'... *shivers*

- The script is based mostly on medieval Berber orthography and modern Senegalese Wolof Ajami (or Wolofal), with minimal influence from Spanish Aljamiado. I emphasized the West and North African elements because that's who is bringing Islam to Anahuac. I tried to take as little influence from Aljamiado as possible since most Aljamiado that survives today wasn't actually from the peak of Andalusi power. During that peak, everyone tried to learn Arabic. It was only during the Reconquista, when spoken Arabic had died out and Islam in Spain seemed to be going the same way, that the need to express spoken Spanish in a script that preserved Islamic heritage--the need for Aljamiado--became pressing.

- The system of full vocalization (using fatha-kasra-damma at all times, even during long vowels) is inspired by Aljamiado and Wolofal. Neither of those languages really has long vowels, so I had to base the long-vowel system off of Berber (They don't have long vowels either, but what they do have is two coherent but separate methods of writing the same short vowels). This gives the script a somewhat alphabetic character.

- Observers may note that various Ajami scripts' letters for /g/ resemble the Arabic "kaf". This is because before the new letters were invented, "kaf" (due to its similar sound) was used to represent /k/ and /g/ in those languages. This being unsatisactory, a similar-looking but graphically distinct letter was soon invented. The Sufis who created this TTL script used that similar-sound principle to assign "ba" to /p/ and "saad" to /tz/, but since Nahuatl has no real competitors (an actual /b/, for example) to those sounds, the choice stuck despite imperfections. For /tl/, a distinct letter based on "ta'" (ڟ) was judged to be necessary due to the distance of the sound from anything in western Islam's sound inventories. As for /ch/, the West African Sufis had developed that character (څ) for their own use so they decided to add it I guess.

- Other flaws in the system include short /e/ and short /i/ looking the same (both use a single kasra). Wolof uses the kasra to represent all of its front vowels, so the script designers probably didn't see an issue with it. I also wanted to stay within Unicode's requirements and what I considered realistic developments (e.g. using the tanwin marks seemed like an oddball choice, as no Ajami script uses them for anything).

- Wa-hamza is generally supposed to be used for labialized consonants and vowels, as in "Cuauhtemoc" (/Kwawtemok/).

- Diphthongs are, in written from, broken up with a waw or ya, as per Aljamiado practice. /oa/ is written "owa", /ai/ becomes "ayi", and so on.

- The sukun is used to break up consonant clusters. Aljamiado did this to an extent, but also had a dumb feature of "smoothing out" clusters by adding silent vowels ("entrar" became "entarar", "primero" became "pirimero"). It would still be pronounced the same way, but just written in imitation of Arabic practice.

Last edited: