They can't just import them from Canadia?Minnesotans need models for their snow men?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Until Every Drop of Blood Is Paid: A More Radical American Civil War

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"You have snow elvesMinnesota we don't have snowmen we have white walkers

wait until u "meet" these snow elves and you may change your tuneYou have snow elves! I need to go and visit sometime!

I've read Sam's chapters is ASOS, I think I've met them just fine, thank you.wait until u "meet" these snow elves and you may change your tune

Nah those are distant relatives we are much tougher and that not all we have...I've read Sam's chapters is ASOS, I think I've met them just fine, thank you.

I just noticed this TL has been nominated for a Turtledove award! Many thanks to @Gaius Julius Magnus for nominating me, and @Worffan101 for seconding the nomination. We've some though competition by excellent TLs written by excellent authors. I'm under no illusions, there are better TL writers out there. Still, and I'm just repeating myself, but I wanted to thank you all for the great support you've showed towards this little project of mine. I'd be very grateful if you could lend me your vote and your support.

It's a good TL, and yeah, there's a great field this year, but I wish you luck all the same, sir.

It's a good TL, and yeah, there's a great field this year, but I wish you luck all the same, sir.

Thanks

Chapter 13: Down with the Traitors, Up with the Stars!

Chapter 13: Down with the Traitors, Up with the Stars!

President Breckinridge was sitting in his office in Richmond, Virginia. He had a gigantic task ahead of him. He had to create an army, build a navy, and consolidate a nation. All tasks more difficult that those Washington had faced, for Washington had been able to build up his country after winning militarily. Breckinridge, on the other hand, had to do both at the same time. This created a series of strange contradictions – he was assuring diplomats that he only wanted peace, while at the same time he was building an army; he was proclaiming that the South only wanted to be alone, while his army was marching on to Washington D.C.

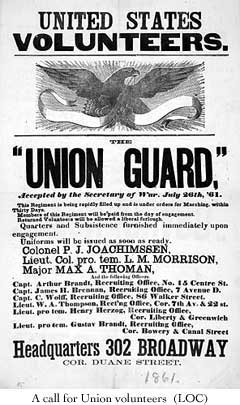

The fact was, Lincoln had outmaneuvered him this time. The prairie lawyer turned statesman showed the Counterrevolutionaries what he could do by maneuvering them into being the aggressors. If the Confederacy was the first to draw blood, the North would be united against them. Just the rumors of a Southern army heading to D.C. was enough to ignite the spirit of the Northern people. From the East and from the West, thousands cheered the stars and stripes and vowed to defend the capital no matter what. The Baltimore riots plus the isolation of Washington was the last drop. People who had before advised caution and reconciliation now clamored for bloody vengeance.

Lincoln’s plan hadn’t been executed perfectly. For one, there truly were no troops to protect Washington, leaving the city defenseless. For how long, neither Head of State was sure. This window of opportunity was priceless, and Breckinridge and many Southerners recognized that it was their best shot at conquering peace for Dixie. But Breckinridge wasn’t sure whether he wanted to “conquer” a peace, or simply negotiate one. Another flaw in Lincoln’s plan was that he overestimated the loyalty of Maryland and its people. But still, Breckinridge told his secretary that Lincoln’s plan “exhibited a perplexing brilliancy.”

The brilliance of Lincoln’s decisions wasn’t apparent to many Southerners, and a lot of Northerners as well. But the fact was that, through his actions, Lincoln had basically told Breckinridge “heads I win, tails you lose”, per the words of historian James M. McPherson. If Breckinridge attacked the North, he would be branded as the aggressor in the eyes of the world, solidify the Northern will to go to war and to win it, and, worst of all, he would start a war in the first place. Breckinridge was painfully aware of the South’s weaknesses and the immense power of the North. “I trust I have the courage to lead a forlorn hope”, said the President whilst under an especially despondent mood.

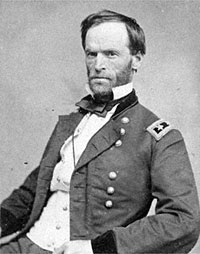

Indeed, when the South and the North were compared in the basis of men, resources, and industry, or in other words, when you pitied the war resources of both sections, it was clear that the North had an immense advantage. Though Breckinridge wasn’t present when the Superintendent of the Louisiana State Military Academy, William T. Sherman, gave a fiery condemnation of the Southern Rebellion, it’s clear that Sherman’s words would have added to his conclusions.

“You people of the South don’t know what you are doing”, the red-bearded West Pointer said, "This country will be drenched in blood, and God only knows how it will end. It is all folly, madness, a crime against civilization! You people speak so lightly of war; you don't know what you're talking about. War is a terrible thing!" Other Southerners shared Breckinridge’s feelings. Robert E. Lee, the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, had given up his US Army commission, declaring that he could not raise his hand against “my birthplace, my home, my children.” Lee exhibit great resolve and skill as a commander, and his high sense of dignity prevented him from expressing much emotion. Nonetheless, he also dreaded war: “I foresee that the country will have to pass through a terrible ordeal, a necessary expiation perhaps for our national sins.”

William T. Sherman

Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, who had wanted to fight as a general in the Army of the Mississippi but was compelled by a strong sense of duty to answer Breckinridge’s call, was also aware of this disparity. Having being Buchanan’s Secretary of War, he had a good idea of the resources of the US. Commander in-chief Johnston also was aware of their disadvantage, but he was a proponent of seizing Washington at once before the North was able to build an army. He was joined in this by General Beauregard, the commander of the Army that was marching on to the Yankee Capital. Both Generals believed the Lincoln government could be brought to its knees by "the crushing victory the fall of the Yankee capital would constitute."

Many people opposed a direct attack. Although his hunger for glory had not yet been sated, Toombs argued against attacking, because that would “inaugurate a civil war greater than any the world has yet seen”. He continued, adding that “it is suicide, murder, and it would lose us every friend at the North. It would wantonly strike a hornets’ nest which extends from mountains to ocean. Legions now quiet will swarm out and sting us to death. It is unnecessary. It puts us in the wrong. It is fatal.” Breckinridge tended to agree with such sentiments. But pro-war Confederates expressed a counterpoint: not attacking would lose Breckinridge his Southern friends; it would allow the Lincoln administration to consolidate and prepare; it would lose the momentary advantage the South enjoyed; and it would discredit the entire Revolution.

Peace could not be negotiated, it had to be asserted, it had to be conquered. That was at least the point many Confederates made. Lincoln had barely 15,000 men, of whom only a faction was in Washington. The Confederacy already had hundreds of thousands of young men. Many had no shoes, no uniform, no arms, and no training. But for all intents and purposes Breckinridge had an army while Lincoln didn’t – but that could change, and it could change soon. If Breckinridge took Washington, that could potentially constitute a fatal blow towards the Lincoln administration, shattering Northern unity and their faith on Lincoln, and showing that the Confederacy was independent and had the means to enforce this independence. But it could also have the opposite effect and unite the North.

What pushed Breckinridge the most was the potential effects on the South. If he didn’t attack, he would be seen as a weak figure, not fit for commanding a new nation in its hour of need. Yancey had introduced him to cheering Richmond crowds with these words: “The man and the hour have met!”. Many were already doubting whether the Alabamian was right. Was Breckinridge truly the man of the hour? “Our new President does nothing at all for our cause. The armies of the Lincolnites will soon come!”, complained an exasperated Richmond clerk. Newspapers demanded action. “Let us take the Yankee capital, and our independence will be secured”, said one, while the Richmond Examiner printed a column asking for "one wild shout of fierce resolve to capture Washington City, at all and every human hazard. That filthy cage of unclean birds must and will be purified by fire." Many expressed similar rhetoric – “we are willing to pledge our hands and hearts for this most holy crusade, but we need to act now”, declared a Virginia officer, while a North Carolinian wrote home that "the defense and survival of our country, of our very lives, depends on whether we can take the Federal city."

Striking the North would unite the South behind Breckinridge, keeping the martial spirit of the people, and it would force Lincoln to either surrender or call for troops. The first option was simply not possible; the second would reek of coercion, and push the Border States towards the Confederacy. These Border States would be all more eager to join their Southern brethren after it was shown that the Confederacy was able to conquer a peace. Britain, France, and other Great Powers would likewise be impressed. Already the London Times was expressing that the North couldn’t win:

It is one thing to drive the rebels from the south bank of the Potomac, or even to occupy Richmond, but another to reduce and hold in permanent subjection a tract of country nearly as large as Russia in Europe. . . . No war of independence ever terminated unsuccessfully except where the disparity of force was far greater than it is in this case. . . . Just as England during the revolution had to give up conquering the colonies so the North will have to give up conquering the South.

With each passing day, the resolve of the Southern people weakened, and Lincoln’s hold over the Border South strengthened. Due to this, Breckinridge decided that he had no option. Attacking would start a war, but at the moment it seemed like one would start anyway, and it would start soon. The best option was to start it under favorable terms. Breckinridge would lose, but Lincoln wouldn’t win. The Southern President was finally pushed forward when the Maryland Convention declared secession from the Union. In April 18th, 1861, the order was given and Beauregard marched on to Washington.

General P. G. T. Beauregard

The capital was submitted under panic. Under the direction of General Scott, the Treasury Building was being fortified for a last stand. Only militias and a couple of regiments were available to defend the city. In April 16th, Lincoln had issued a call for 25,000 volunteers to protect the National Capital from “a hostile rebellion” which means "to direct an attack towards the seat of the government". The Northern President had been greatly troubled. He needed troops to defend his capital, but issuing a general call would start the war in the worst possible moment. He needed to paint Breckenridge as the aggressor, but also maintain the image of his own government as strong enough to lead. Furthermore, he had to threat carefully around the not-yet seceded states, especially Maryland and Kentucky.

Events surrounding Kentucky will be discussed later. For the moment, Maryland was a more pressing issue. The capital had been cut off the rest of the nation in April 10th, but in April 13th General Benjamin Butler was able to reopen a railway line through Annapolis, and arrive with 2 regiments: the 7th New York and the 6th Massachusetts. Now able to communicate with the states and the rest of the Federal government, Lincoln issued two proclamations: the first calling for the 25,000 volunteers, and the second asking Congress to meet in Philadelphia.

The first proclamation was carefully crafted as to not offend the sensibilities of the Border South. It made it clear that the troops would only be used to defend Washington and not to go on the offensive. The small numbers of troops called was another reassurance of that. Furthermore, it did not call for troops from the Border South, though some newspapers felt the need to make it clear that “the President has the power and the right to call for the men of any state.” The proclamation was mild enough to not provoke Kentucky, Kansas, Tennessee, or Arkansas, all of which had conventions in session, to secede. But Maryland was different.

The governor of Maryland, George William Brown, was a pro-Confederate, pro-Slavery man. Unhappily for Lincoln, panic regarding the admission of Kansas as a slave state had provoked a pro-slavery reaction in Maryland, which pushed Brown to run for the governorship as a Democrat against the Know-Nothing Thomas Hicks. Brown had wanted to run for mayor of Baltimore, but he was convinced that he needed to protect his state against the Black Republicans. When South Carolina seceded, Brown had called the legislature into session. A convention was rejected, but after Virginia seceded one was finally elected. It returned a strong Conditional Unionist majority, which frustrated Brown and other secessionists. The convention voted down an ordinance of secession, after which Brown took action. He was the one who ordered Maryland militia and rioters to prevent the passing of Union troops no matter what. “A tyrant’s heel is on thy shore, Maryland!”, he thundered, “it’s time to raise our swords and, with a manly thrust repeal him from our sacred home!”

Confederate flags were flown in seemingly every window in Baltimore, and effigies of Lincoln and other Republicans were burned. Militia companies were raised, the so called “State Guard” regiments. But the Unionists of Maryland were also spurred into action. Rival “Home Guard” Unionist regiments were also raised, and Unionist organized an election for a new state assembly, an effort that received the approval and support of Lincoln. Denouncing this “appropriation” of his legal duties, Brown asked the Convention to consider an ordinance of secession. Lincoln considered sending troops to stop the Convention, but decided against it.

This proved to be the right choice. Though some members still talked about Southern rights and called Lincoln a tyrant, Brown’s actions had solidified the Unionism of the Convention. Even the location was telling – the pro-Union city of Frederick. Brown decided to not recognize the Convention, instead turning to the Legislature. Dominated through gerrymandering by pro-Slavery Southern Democrats who represented Southern Maryland and the shores of the Chesapeake, the Legislature was ripe for secession. When news came of a clash of arms in Brotherton, a small town just off the Annapolis railway, in April 16th, the Legislature acted and passed the ordinance of secession, fearing that the troops encountered were the abolitionist, ready to “John Brown” them.

The Union regiment was the 8th Massachusetts, which had had to dismount the train near Brotherton. There the soldiers started to repair the damaged rail, when State Guard regiments appeared. Calling themselves minutemen and swearing that they would not allow the Union to pass through, they charged. “Remember the stern example of the Minutemen of Lexington! Remember the immortal courage of the Maryland militia at Guilford! Stand firm, and attack!” yelled the Rebel commander.

The Battle of Brotherton was anti-climactic, with the rebels scampering to Baltimore and the Union soldiers to Washington after a futile exchange of shots that only produced a dozen casualties. Still, these were some of the first casualties of the Civil War. Lincoln received the regiment in Washington, while in Baltimore the Legislature denounced the “wicked, inhumane, despotic” acts of the Lincoln government. It promptly passed the ordinance of secession. The Convention at Frederick then declared itself the new government of Maryland, electing Hicks, now a National Unionist, as interim governor. Maryland thus was divided between two governments. However, for the moment Brown’s rebel government held more power. Brown quickly asked for admission into the Confederacy, and for Breckinridge to send troops to protect Maryland from the expected Union military buildup. He also offered to attack Washington from the North with his militias.

George William Brown

Something like that had been expected by Lincoln, who had arranged for a quick evacuation of Washington should his small army be unable to hold off the Confederates. His second proclamation, not made public directly, also anticipated the need to evacuate the capital. After the end of the March special session, he asked Congress to reconvene not in Washington, but in Philadelphia. The proclamation found its way into the press, where the opposition ran away with the story, something that weakened the Lincoln administration and most likely slowed down significantly the flow of volunteers. Some even reported that the Capital had already been surrendered! But Lincoln was able to turn the news around and make it clear that the Rebels were coming, but that they could be stopped. His call for volunteers plus the announcement that Lincoln would remain in Washington until the last moment served to galvanize the North. More tragic and admirable for many was the fact that Lincoln had sent Vice-President McLean and some key members of his cabinet to Philadelphia, most likely so that they could assume control should Lincoln be captured or killed.

The strategic choice of Philadelphia as the new capital had not taken long. Besides its prime location which allowed it to easily receive foreign diplomats and communicate with the east and the west, Philadelphia was protected by several rivers, dismissing the threat of the Confederate army. Furthermore, the large and cosmopolitan city was firmly Unionist, and it enjoyed great prestige and historical significance as the place where the First and Second Continental Congresses plus the Constitutional Convention met. Choosing the birthplace of the nation sent a firm message to the rebels who were trying to destroy that nation. Other options like New York and Boston were ruled out because the former’s loyalty was suspect while the later would probably alienate moderates and was too far away from the battlefield. With Philadelphia thus selected as the new seat of government, a lot of the apparatus was moved there by sea in the weeks following Virginia's secession.

Still, despite all his preparations, when the rebel flag was spotted outside Washington in April 19th, Lincoln almost gave in to despair. Breckinridge had finally given Beauregard the go ahead in April 18th, after receiving news of Maryland’s secession. The event had put him in a critical spot. If he couldn’t show other states’ secessionists that the Confederacy would and could protect them if the seceded, he would basically lose all hope he had for welcoming the Border South into his new nation. Without these critical states, the Confederacy’s hope for survival was dim at best. Feeling himself trapped, he approved Beauregard’s plans.

The South had around 40,000 men under arms in Virginia, facing the around 15,000 Lincoln had managed to scrape out of incomplete regiments and militia. Of this 40,000, Beauregard could use only 25,000. The others lacked equipment, were unorganized, or had fallen sick. Still, his troops were superior to the ragtag bunch of militia of Lincoln. Some were not even soldiers, but civilians organized in volunteer companies. Feeling confident, Beauregard forded the Potomac through the Chain Bridge, some two miles to the Northeast of the city. The Federals had failed to destroy it, and when they saw him approaching they quickly withdrew to the city. Beauregard started his advance at the Rock Creek Road, but received intelligence that informed him of the existence of makeshift Fort Saratoga. To circumvent them, Beauregard swerved east to the Rockville Road, and started to advance again.

There, he received a petition of the commander of the Maryland Militia. The Marylanders had been advancing by the Road to Baltimore, but they didn't feel confident on their own strength after their embarrassing performance at Brotherton. They asked Beauregard to send Confederate regulars to meet with them at the halfway point of Seventh Street Road, just north of another makeshift fort. Knowing that he needed to successfully protect the Marylanders from defeat, however unlikely it was, and the optics of them fighting alongside other Confederates mere days after succeeding would help the Southern cause in the Border, Beauregard accepted and sent the Virginia Colonel Thomas J. Jackson. Showing the skill that would make him famous in the future, Jackson marched his men to the meeting point at an astounding velocity. There were now two Confederate columns: Beauregard with 20,000 men and Jackson with 8,000.

The Union soldiers bravely held off the rebels at the Rock Creek and the still not completed but appropriately named Fort Bunker Hill. Despite their strong defenses and their artillery, the Union men were “green” troops, which even Winfield Scott considered useless. The Rebels, to be fair, were also “green”, but they enjoyed several advantages. For one, Beauregard possessed a skilled net of spies within Washington; Maryland rebels also made sure to ax trees, destroy roads and railways, and do everything to slow down the already slow Union regiments. They also enjoyed a psychological edge over their adversaries.

But the Union soldiers showed a resilience and bravery that would characterize them in later years. Despite being outnumbered, despite their inexperience and the general sense of hopelessness that gripped them, they fought on, decided to not give up their capital unless every man had fallen. They made good of their promise – at the end of the day, the sun fell over 4,000 rebels, more than double the Union casualties. Still, the sheer force of numbers and the ferocity of the Confederates pushed the Union soldiers to the breaking point, and a rout took place. Lincoln was forced to evacuate, taking a boat down the Potomac together with Scott, many important archives and art pieces, and whatever and whoever else he could take with him. He implored the surviving soldiers to go with him, but they solemnly answered that they would stay until the end. With tears in his eyes, the President thanked them profusely, and set forth to the Chesapeake, where heavily armed boats were, ready to protect him as he traveled north to Philadelphia.

By the next day, April 20th, Washington had fallen. Many civilians had been evacuated towards the Unionist parts of Maryland after the Legislature approved the ordinance of secession. Only clerks and militias remained, some fortified within the Senate chambers and the Treasury. The rebels looted and burned buildings and homes, including the Capitol and the White House, which blazed for the second time. This time, the fire was more destructive. The Statue of Freedom, built to crown the dome of the unfinished Capitol, was also destroyed. The significance of the Slavers destroying it was not lost. Finally, the last defenders of Washington surrendered, and the Confederate Stars and Bars rose over the smoking capital.

Washington burns

Far from destroying the Northern will, this attack pushed the North towards fury and outrage, and a desire to crush out treason no matter what. From his new desk in Philadelphia, President Lincoln issued a proclamation calling for 150,000 volunteers for three years of service to quell a “rebellion too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings”. The reaction was overwhelming. From all corners of the nation came a giant scream, as millions swore allegiance to the nation and clamored for the blood of traitors.

In New York, known for its Southern sympathies, half a million people turned out for a Union rally. "I look with awe on the national movement here in New York and all through the Free States," said a lawyer, while a New York woman added that “it seems as if we never were alive till now; never had a country till now." From Boston, a woman wrote that “The whole North stood up as one man… I have never seen anything like this before. I had never dreamed that New England... could be fired with so warlike a spirit.” The West was alight with the same electric energy: "In every city, in every village and house you can hear the cheers. I've never seen such popular excitement!" wrote a Michigan man, while in Springfield, Illinois, thousands met to cheer the President and "declare that whatever sacrifice it takes, they will not stop until every single rebel is hanged, and every city of the South is ablaze", per one spectator. "All squeamish sentimentality should be discarded, and bloody vengeance wreaked upon the heads of the contemptible traitors who have provoked it by their dastardly impertinence and rebellious acts", clamored a newspaper. “Let our enemies perish by the sword, let them die in the fire of condemnation!”, said others. None other than Stephen A. Douglas issued a fiery declaration: "There are only two sides to the question. Every man must be for the United States or against it. There can be no neutrals in this war, only patriots—or traitors."

The American Civil War had begun.

Last edited:

Ahem. Chesapeake.Southern Maryland and the shores of the Cheapskate

Otherwise, fantastic work. I can't help but guess that burning Washington will cause more trouble than it's propaganda worth for Breckinridge...

also, I imagine that with a much more anti-Slavery Lincoln here, the British will be even less likely to support the Confederacy than OTL, because even in OTL, the British Public was extremely pro-union, I imagine that they would be even more so, here.

Wow, the Second Burning of Washington. The South really fucked up there. I can imagine parallels being drawn between Breckenridge and George III.

Que the sherman memes]

Well the rebels burned dc now let’s sherman lose on them!

Brown had wanted to run for mayor of Maryland

Mayor of Maryland?

Not when you consider the defenses- you need to cross the Susquehanna to reach it, and it is a bitch to cross, especially upriver. Any army would be screwed if they tried to hit the city.Well, saw that coming. Although methinks Philadelphia is a trifle too close to the Confederacy.

Threadmarks

View all 80 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 57: The Liberty Hosts Are Advancing! Appendix: Wikiboxes of US Elections 1854-1864 Chapter 58: Shall Be Paid by Another Drawn with the Sword Side-story: "A Baseball Legend" Side-story: "A deserter and a freeman." Epilogue: The Union Forever Bonus: Fun-facts and alternate scenarios Side-story: "A Story from Dr Da Costa"

Share: