Could this promt the russians to get into eastern turkerstan? I mean, seems like an apropiate reaction to the british zeising tibet: you take the south west, I take the north west, right? I doubt that London would oppose or that the chinese would be in position to do anything.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Anglo-Saxon Social Model

- Thread starter Rattigan

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 190 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Alexander Ministry (2024-2025) Miliband Ministry (2025-2026) Western Canada Independence Referendum, 2024 Western Australia Independence Referendum, 2027 Second Yugoslav War (2009-2029) Stewart Ministry (2026-2031) Commonwealth Election of 2031 World Map, 31 December 2030Could this promt the russians to get into eastern turkerstan? I mean, seems like an apropiate reaction to the british zeising tibet: you take the south west, I take the north west, right? I doubt that London would oppose or that the chinese would be in position to do anything.

I agree with you on the latter but disagree on the former - geopolitics hardly brings out peoples' consistency.

Anyway, I'll be putting up another couple of updates today, one on domestic social reforms and another on the military. I know a lot less about the latter so feel free to provide any constructive criticism or abuse that comes to mind.

So, is this going to result in the UK having something closer to a "generic European country politics" ITTL?

Military Reforms 1905-10

Si vis pacem, para bellum: The Asquith Reforms, 1908-09

Edmund Allenby - The Lightning General

With the radical wing of the party in charge of domestic reforms, the final remaining province of the Liberals’ Gladstonians came in the War Office. When the Liberals returned to power in 1905, Henry Campbell-Bannerman was installed as Secretary for War. While this was initially thought to be a prestigious appointment for the department – Campbell-Bannerman was respected on a cross-party basis and had the additional cachet of having served in every Liberal government since the 1860s – and was widely held to have expertise in military affairs (he had been a parliamentary assistant to William Cardwell in carrying out the Cardwell Reforms). However, it rapidly became clear that Campbell-Bannerman had been cut out of the inner workings of the Liberal government and he was more or less ineffective in his role up to his death in April 1908.

Perhaps the only lasting effect of Campbell-Bannerman’s tenure at the War Office was his ordering of the creation of the Land-Ship Committee in February 1905 under the chairmanship of R.E.B. Crompton, to look into the possibilities of developing armoured vehicles for use in the military. The existence of this committee was kept secret from the rest of the cabinet until July 1905, when the first prototype tracked vehicle (codenamed ‘the tank’ in order to conceal its nature, a word which soon came to stand in for the entire concept) was unveiled. The original Mark I tank proved to have too high a centre of gravity to negotiate the broken ground and trechlines that was anticipated on future battlefields but the subsequent Mark II demonstrated the rhomboidal shape and sponson weapons that would become iconic. After a demonstration in January 1906 to members of the cabinet (in utmost secrecy), the War Office placed an order for 150.

By the time H.H. Asquith took over from Campbell-Bannerman as Secretary of War in April 1908, the ordered tanks had been delivered but the extreme secrecy under which they were held meant that the infantry, cavalry and artillery had not had the chance to train with these new vehicles (and, it was alleged, some brigade commanders were even unaware of their existence). Furthermore, the Second Boer War and the Anglo-Tibet War, along with supply difficulties during the Anglo-Egyptian War, had revealed the bad communication between the different armed forces of the empire and the problems inherent in trying to coordinate the tactics and a number of different organisations each with different histories and combat doctrines.

With an analytical mind that enjoyed working with numbers and chairing committees, Asquith was the ideal person for the job and set himself the task of reorganizing the different military forces of the empire in conjunction with the CID (although one of the first of these ‘Asquith Reforms’ was renaming the CID the Imperial Chiefs of Staff or “ICS”). Although the Dominions continued to raise their own land armies (and coast guards, where relevant), the budding Australian and Canadian navies and the longer-established Royal Indian Navy were scrapped and control was centralised with the Royal Navy under the command of the ICS. The secrecy around tanks was lifted (albeit only to an extent – they remained unknown to most of the public) and the active home army was reorganized into an active force of three cavalry divisions and three mixed infantry and mechanized divisions. This reorganization allowed a number of surplus infantry and artillery brigades to be disbanded, meaning that the government actually saved money. To support the active army, the various Yeomanry and Reserve forces were reorganized into the 28-division Territorial Force. In October 1908, the 11th Hussars became the first cavalry regiment to ‘mechanise’ permanently (i.e. get rid of their horses and replace them with tanks and armoured cars).

Asquith was not able to get agreement in the ICS to amalgamate all British and Dominion forces into a single army. However, he was able to get agreement as to the preparation of a single manual in 1907 that would be distributed to the armies and practiced at the combined empire military exercises. The man chosen to draft the manual was Edmund Allenby, a major-general who had served with distinction in the Second Boer War. Allenby was not known for being the most cerebral military mind in the world but he was experienced, tactically and strategically astute, open to new ideas and technology and had experience of commanding Australian and Canadian troops during the Second Boer War. Furthermore, he was well liked by the other staff officers both in Camberley and on the ICS, something which was regarded as vital considering that the writing process consisted of widespread consultation with other commanders in order to create a synthesis of the best ideas.

When it was published in 1909, the manual (nicknamed ‘Plan 1914’ for the date of anticipated implementation of all of its provisions) proposed a big break with previous orthodoxy, which had stressed good defensive preparations combined with maneuverable cavalry formations in order to destroy the opposing forces. Instead, Plan 1914 called for rapid strikes lead by mechanized infantry to punch holes through the opposing front line and make advances to the enemy’s rear, destroying lines of supply and communication. In the ensuing confusion, the enemy’s command could be eliminated. Allenby memorably described this kind of assault as “a shot to the brain.”

The manual was controversial amongst an older breed of commander but was generally accepted thanks to rapid advances in technology. In 1908, 2,000 of the heavier Mark IV tanks had been ordered, alongside the smaller Mark III tanks (of which there were 4,500 in service), creating the conditions for heavy tanks to punch holes in the opposition line, with lighter tanks and cavalry exploiting the breakthroughs. Research was also put into the potential use of planes, not only for reconnaissance but also for strafing runs on enemy infantry and bombing attacks on supply lines and artillery. Artillery doctrine was also changed to place emphasis on smaller, mobile guns which were capable to providing a rolling barrage ahead of the advancing tanks and infantry. Through the deployment of this fast-moving, combined-arms attack, the enemy would, in theory, be continually off-balance and unable to respond. The doctrine soon came to be known as ‘Lightning Warfare’ and Allenby himself as ‘The Lightning General.’

Edmund Allenby - The Lightning General

With the radical wing of the party in charge of domestic reforms, the final remaining province of the Liberals’ Gladstonians came in the War Office. When the Liberals returned to power in 1905, Henry Campbell-Bannerman was installed as Secretary for War. While this was initially thought to be a prestigious appointment for the department – Campbell-Bannerman was respected on a cross-party basis and had the additional cachet of having served in every Liberal government since the 1860s – and was widely held to have expertise in military affairs (he had been a parliamentary assistant to William Cardwell in carrying out the Cardwell Reforms). However, it rapidly became clear that Campbell-Bannerman had been cut out of the inner workings of the Liberal government and he was more or less ineffective in his role up to his death in April 1908.

Perhaps the only lasting effect of Campbell-Bannerman’s tenure at the War Office was his ordering of the creation of the Land-Ship Committee in February 1905 under the chairmanship of R.E.B. Crompton, to look into the possibilities of developing armoured vehicles for use in the military. The existence of this committee was kept secret from the rest of the cabinet until July 1905, when the first prototype tracked vehicle (codenamed ‘the tank’ in order to conceal its nature, a word which soon came to stand in for the entire concept) was unveiled. The original Mark I tank proved to have too high a centre of gravity to negotiate the broken ground and trechlines that was anticipated on future battlefields but the subsequent Mark II demonstrated the rhomboidal shape and sponson weapons that would become iconic. After a demonstration in January 1906 to members of the cabinet (in utmost secrecy), the War Office placed an order for 150.

By the time H.H. Asquith took over from Campbell-Bannerman as Secretary of War in April 1908, the ordered tanks had been delivered but the extreme secrecy under which they were held meant that the infantry, cavalry and artillery had not had the chance to train with these new vehicles (and, it was alleged, some brigade commanders were even unaware of their existence). Furthermore, the Second Boer War and the Anglo-Tibet War, along with supply difficulties during the Anglo-Egyptian War, had revealed the bad communication between the different armed forces of the empire and the problems inherent in trying to coordinate the tactics and a number of different organisations each with different histories and combat doctrines.

With an analytical mind that enjoyed working with numbers and chairing committees, Asquith was the ideal person for the job and set himself the task of reorganizing the different military forces of the empire in conjunction with the CID (although one of the first of these ‘Asquith Reforms’ was renaming the CID the Imperial Chiefs of Staff or “ICS”). Although the Dominions continued to raise their own land armies (and coast guards, where relevant), the budding Australian and Canadian navies and the longer-established Royal Indian Navy were scrapped and control was centralised with the Royal Navy under the command of the ICS. The secrecy around tanks was lifted (albeit only to an extent – they remained unknown to most of the public) and the active home army was reorganized into an active force of three cavalry divisions and three mixed infantry and mechanized divisions. This reorganization allowed a number of surplus infantry and artillery brigades to be disbanded, meaning that the government actually saved money. To support the active army, the various Yeomanry and Reserve forces were reorganized into the 28-division Territorial Force. In October 1908, the 11th Hussars became the first cavalry regiment to ‘mechanise’ permanently (i.e. get rid of their horses and replace them with tanks and armoured cars).

Asquith was not able to get agreement in the ICS to amalgamate all British and Dominion forces into a single army. However, he was able to get agreement as to the preparation of a single manual in 1907 that would be distributed to the armies and practiced at the combined empire military exercises. The man chosen to draft the manual was Edmund Allenby, a major-general who had served with distinction in the Second Boer War. Allenby was not known for being the most cerebral military mind in the world but he was experienced, tactically and strategically astute, open to new ideas and technology and had experience of commanding Australian and Canadian troops during the Second Boer War. Furthermore, he was well liked by the other staff officers both in Camberley and on the ICS, something which was regarded as vital considering that the writing process consisted of widespread consultation with other commanders in order to create a synthesis of the best ideas.

When it was published in 1909, the manual (nicknamed ‘Plan 1914’ for the date of anticipated implementation of all of its provisions) proposed a big break with previous orthodoxy, which had stressed good defensive preparations combined with maneuverable cavalry formations in order to destroy the opposing forces. Instead, Plan 1914 called for rapid strikes lead by mechanized infantry to punch holes through the opposing front line and make advances to the enemy’s rear, destroying lines of supply and communication. In the ensuing confusion, the enemy’s command could be eliminated. Allenby memorably described this kind of assault as “a shot to the brain.”

The manual was controversial amongst an older breed of commander but was generally accepted thanks to rapid advances in technology. In 1908, 2,000 of the heavier Mark IV tanks had been ordered, alongside the smaller Mark III tanks (of which there were 4,500 in service), creating the conditions for heavy tanks to punch holes in the opposition line, with lighter tanks and cavalry exploiting the breakthroughs. Research was also put into the potential use of planes, not only for reconnaissance but also for strafing runs on enemy infantry and bombing attacks on supply lines and artillery. Artillery doctrine was also changed to place emphasis on smaller, mobile guns which were capable to providing a rolling barrage ahead of the advancing tanks and infantry. Through the deployment of this fast-moving, combined-arms attack, the enemy would, in theory, be continually off-balance and unable to respond. The doctrine soon came to be known as ‘Lightning Warfare’ and Allenby himself as ‘The Lightning General.’

Dilke Ministry (1905-10)

Peace, Redistribution and Reform: The New Liberals in Power, 1906-10

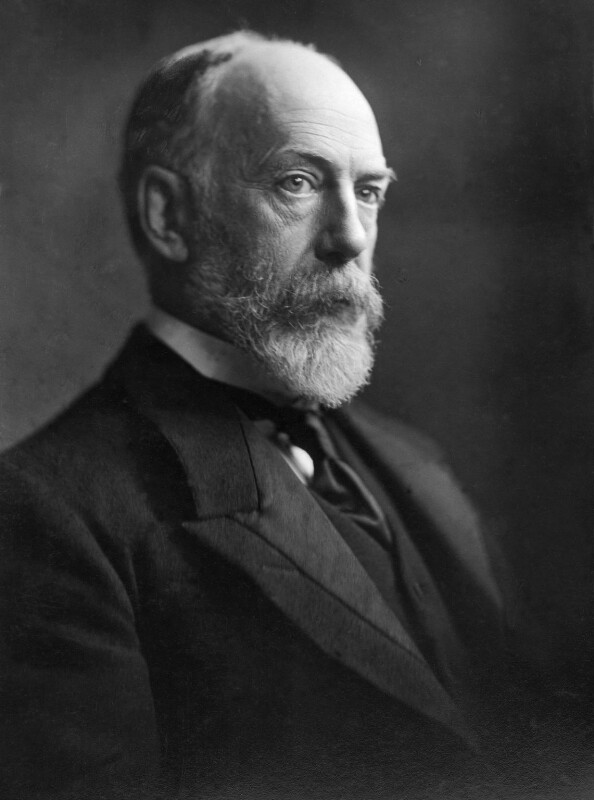

Sir Charles Dilke - The Last of the Whig Radicals

Although the incapacitation and forced retirement of Chamberlain so soon after his greatest triumph was an enormous psychological blow to the Liberals, they still had a massive majority in Parliament, more or less complete control over the sinews of legislative power and enormous public support. With this in mind, the party turned its attention to its transformative domestic agenda, attempting to not only carry through their manifesto commitments but lock themselves into power for the foreseeable future.

Many Liberals had been growing increasingly concerned about the potential challenge of Labour in the future. Rather lost amidst the massive Liberal gains, Labour had picked up 27 seats in 1905 to cement their position as a coherent third party. The fact that Labour was, effectively, the political face of the trades union movement ensured that it was well funded and had lasting power, especially given the large numbers of working class voters now enfranchised. During 1904-5, the parties had struck an informal alliance in order to lock out the Conservatives in certain target seats but few believed that such an arrangement could last for long: although the radical wing of the Liberals found itself closely aligned with Labour on many issues, there could be no doubt that the long-term future of the parties were as rivals. As such, the Liberals rolled out a series of policies designed to curry the female vote and peel off voters otherwise heavily influenced by their union. The fact that they aligned with a number of the Liberals’ long-term principles was all to the better.

Dilke had been a private supporter of women’s suffrage for some time and in his first six months in office his government passed the Sex Disqualification Removal Act 1906, which equalized the voting rights of men and women (by removing property disqualifications and reducing the age at which women could vote to 21) and removed all disqualifications of women from public life (for example, from serving on juries, receiving university degrees or being qualified lawyers). In 1907, the first minimum wages were introduced for agricultural workers, albeit at a rate not notably higher than the market rate. This was followed, in 1908 and 1909, with the Workmen’s Compensation (Silicosis) Act and the Blind Persons Act, respectively. Although both pieces of legislation can hardly be considered generous by contemporary standards, they were expansive for their time and represented the first time that the British government attempted to provide state aid for disabled and injured labourers outside of the strictures of the Poor Law.

The Poor Law itself remained in place, despite mooted attempts by Charles Hobhouse to replace it. However, the successive reforms of various Liberal and Conservative governments since the 1870s had progressively centralized much of British government and rendered much of the Law's contents moot. That being said, there remained significant differences between the quality of welfare provision across the country: radical strongholds such as Bermondsey and Birmingham retained their excellent services but other parts of the country (notably rural areas, where the dispersal of the population made delivery much harder) had far worse reputations.

But, while the government took power away from local councils in the form of welfare, it gave something back in the form of housing. Aside from its social reforms, one of the most obvious physical consequences of Dilke’s government was probably the Town Planning and Housing Act 1909, which provided further subsidies for local governments to demolish slums and build social housing in their place. Around 250,000 council-owned houses were built in the first four years of this act, supplemented by 30,000 privately-built houses which received government subsidies also provided for in the act. These changes not only created the rows of distinctive terraced housing so closely-associated with the late-Edwardian period but also ensured that local councils (taken together) had become the country’s largest landlords by 1919.

With social relations pacific, the economy growing and the Conservatives largely neutered in their Parliamentary opposition, Dilke asked for a dissolution and went to the country in December 1910.

Sir Charles Dilke - The Last of the Whig Radicals

Although the incapacitation and forced retirement of Chamberlain so soon after his greatest triumph was an enormous psychological blow to the Liberals, they still had a massive majority in Parliament, more or less complete control over the sinews of legislative power and enormous public support. With this in mind, the party turned its attention to its transformative domestic agenda, attempting to not only carry through their manifesto commitments but lock themselves into power for the foreseeable future.

Many Liberals had been growing increasingly concerned about the potential challenge of Labour in the future. Rather lost amidst the massive Liberal gains, Labour had picked up 27 seats in 1905 to cement their position as a coherent third party. The fact that Labour was, effectively, the political face of the trades union movement ensured that it was well funded and had lasting power, especially given the large numbers of working class voters now enfranchised. During 1904-5, the parties had struck an informal alliance in order to lock out the Conservatives in certain target seats but few believed that such an arrangement could last for long: although the radical wing of the Liberals found itself closely aligned with Labour on many issues, there could be no doubt that the long-term future of the parties were as rivals. As such, the Liberals rolled out a series of policies designed to curry the female vote and peel off voters otherwise heavily influenced by their union. The fact that they aligned with a number of the Liberals’ long-term principles was all to the better.

Dilke had been a private supporter of women’s suffrage for some time and in his first six months in office his government passed the Sex Disqualification Removal Act 1906, which equalized the voting rights of men and women (by removing property disqualifications and reducing the age at which women could vote to 21) and removed all disqualifications of women from public life (for example, from serving on juries, receiving university degrees or being qualified lawyers). In 1907, the first minimum wages were introduced for agricultural workers, albeit at a rate not notably higher than the market rate. This was followed, in 1908 and 1909, with the Workmen’s Compensation (Silicosis) Act and the Blind Persons Act, respectively. Although both pieces of legislation can hardly be considered generous by contemporary standards, they were expansive for their time and represented the first time that the British government attempted to provide state aid for disabled and injured labourers outside of the strictures of the Poor Law.

The Poor Law itself remained in place, despite mooted attempts by Charles Hobhouse to replace it. However, the successive reforms of various Liberal and Conservative governments since the 1870s had progressively centralized much of British government and rendered much of the Law's contents moot. That being said, there remained significant differences between the quality of welfare provision across the country: radical strongholds such as Bermondsey and Birmingham retained their excellent services but other parts of the country (notably rural areas, where the dispersal of the population made delivery much harder) had far worse reputations.

But, while the government took power away from local councils in the form of welfare, it gave something back in the form of housing. Aside from its social reforms, one of the most obvious physical consequences of Dilke’s government was probably the Town Planning and Housing Act 1909, which provided further subsidies for local governments to demolish slums and build social housing in their place. Around 250,000 council-owned houses were built in the first four years of this act, supplemented by 30,000 privately-built houses which received government subsidies also provided for in the act. These changes not only created the rows of distinctive terraced housing so closely-associated with the late-Edwardian period but also ensured that local councils (taken together) had become the country’s largest landlords by 1919.

With social relations pacific, the economy growing and the Conservatives largely neutered in their Parliamentary opposition, Dilke asked for a dissolution and went to the country in December 1910.

Last edited:

So, is this going to result in the UK having something closer to a "generic European country politics" ITTL?

Not quite sure I buy the idea that there’s a “generic” European politics but I know what you mean. Well, I said I was inspired by a blog about how the UK could’ve been Sweden so kind of but I think the electoral system is so different that we won’t see an exact copy.

Not quite sure I buy the idea that there’s a “generic” European politics but I know what you mean. Well, I said I was inspired by a blog about how the UK could’ve been Sweden so kind of but I think the electoral system is so different that we won’t see an exact copy.

Will the UK get PR at some point?

Will the UK get PR at some point?

Probably not. I always think that PR is so foreign to the political traditions of the UK that its implementation seems so unlikely (and I've never seen an alt convincingly give a scenario). But there will be new and exciting electoral systems coming.

Probably not. I always think that PR is so foreign to the political traditions of the UK that its implementation seems so unlikely (and I've never seen an alt convincingly give a scenario). But there will be new and exciting electoral systems coming.

Considering that STV (in its modern form) was invented by a Brit, I don't think it's all that alien.

However, I will look forwards to the new electoral systems.

Considering that STV (in its modern form) was invented by a Brit, I don't think it's all that alien.

However, I will look forwards to the new electoral systems.

Single transferable vote is very far from proportional representation. You still have a single representative per electoral district, and all this entails for local elections. It's just a bit fairer about allocating that one seat.

Maybe a hybrid system like Germany, where a candidate is elected first for the district, then the remaining unused votes are assigned to a proportional pool?

I think you've confused STV with AV/Instant Run off voting. Both involve ranking candidates by preference, the difference is that STV takes place in multi member districts, and is therefore a proportional system.Single transferable vote is very far from proportional representation. You still have a single representative per electoral district, and all this entails for local elections. It's just a bit fairer about allocating that one seat.

I think you've confused STV with AV/Instant Run off voting. Both involve ranking candidates by preference, the difference is that STV takes place in multi member districts, and is therefore a proportional system.

You're right, sorry about the confusion.

Single transferable vote is very far from proportional representation. You still have a single representative per electoral district, and all this entails for local elections. It's just a bit fairer about allocating that one seat.

Maybe a hybrid system like Germany, where a candidate is elected first for the district, then the remaining unused votes are assigned to a proportional pool?

I'm tempted to go for a mixed member-proportional system whereby each person gets two votes, one for a candidate in normal FPTP (making up maybe 75% of MPs) and one for a party to be allocated along a party list basis (the other 25%). That sounds to me like the sort of odd little compromise the British constitution would throw up but I've not firmly decided - we're probably at least a decade away from that in any event.

Not sure what I want to do with the Lords, though.

Indeed, your idea of a “Scandinavian”, socially democratic Britain might end up resembling New Zealand in a lot of ways (albeit far more wealthy and populous).

Well, New Zealand up until the 1980s at least...

The General Election of 1910

Natural Wastage: The Election of 1910

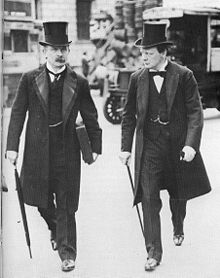

David Lloyd George (l) and Winston Churchill (r) - allies who represented the Liberal unity of the upwardly-mobile lower-middle classes and the progressive-minded aristocracy

Despite a large turnover in seats, commentators at the time regarded the 1910 election as one of the least consequential of recent political events. In a marked contrast with his predecessor and with recent elections, Dilke did very little personal campaigning outside of his Chelsea seat and instead the bulk of Liberal electioneering was done by Dilke’s acolytes, most notably Lloyd George in Wales, Churchill in Scotland, Dillon in Ireland and Austen Chamberlain (assisted, when he was able to, by his father) in the Midlands. While this inevitably lead to a degree of difference between the Liberal message in different parts of the county – famously, in a speech in Birmingham, Chamberlain claimed that the Liberals would immediately move to have a devolved English assembly in the city, which earned him a private rebuke from Dilke – but nothing that appeared to have had a consequential impact on the election. The informal electoral pact with Labour was dissolved, although local Liberal parties did not run serious candidates in seats Labour already held (mostly because of their moribund local organisations).

The Liberals’ laid back attitude may have had something to do with the disunity in the Conservative party. While Liberal splits over trade had largely been settled by 1900 (and before then had often taken place under the cover of debates about Ireland in the 1880s), for the Conservatives they were now out in full force. The pro-tariff wing of the party – largely the most strongly imperialist wings or those most close to the landed interest – saw the benefits of protectionism for agricultural products and closer unity within the Empire. On the other hand, the free trade wing argued that tariff reductions would lower prices, enable the government to scrap the Liberal food subsidies and save money. Many of the free trade Tories also argued for a closer alliance with the French and Americans (perhaps even joining the Triple Entente). While the Conservative manifesto wasn’t as comically contradictory as it had been in 1905, it still failed to paper over the party’s divisions.

In the end, the Liberals lost 76 seats, of which 11 were to Labour (who ran an efficient campaign in their urban targets). While this would have been considered an election-losing result in almost any other circumstance, in the context of the 1904-05 these loses could simply be written off as, in Churchill’s famous words, “natural wastage.” No ministers lost their seats and the party could continue to pass its legislative agenda with a comfortable working majority of over 60.

A total gain for the Conservatives of nearly 70 could also, on most nights, be regarded as a great result. But here it only caused the party to fall further into recrimination, partly because it was their second successive defeat and partly because power seemed to now be within reach (if only tenuously). Arthur Balfour resigned from the leadership of the party in February 1911 and it soon fell into a vigorous internal fight between protectionists such as Bonar Law and Walter Long against free-traders, most notably Charles Ritchie and Michael Hicks-Beach. Long would eventually emerge as the leader but he could do so only by promising Ritchie and Hicks-Beach prominent positions in any future government. As Bonar Law privately commented at the time, this promise was easy to make in opposition but hard to keep in government.

However, whatever hopes the Liberals may have had for a few months of smooth government were dashed by tragedy within a month of the election. Dilke, dressing for a dinner with Lloyd George and Churchill in Number 10, died very suddenly of a heart attack in January 1911, meaning that, for the second election in a row, the Liberals were required to replace an election-winner struck down by illness. This time, however, there was less doubt about the outcome, as Lloyd George was confirmed as Prime Minister eleven days after Dilke’s death, making what many assumed to be his natural promotion a few years earlier than planned. With a small reshuffle of the cabinet – the most notable change of which was the promotion of Churchill to the position of Chancellor – Lloyd George prepared to govern.

David Lloyd George (l) and Winston Churchill (r) - allies who represented the Liberal unity of the upwardly-mobile lower-middle classes and the progressive-minded aristocracy

Despite a large turnover in seats, commentators at the time regarded the 1910 election as one of the least consequential of recent political events. In a marked contrast with his predecessor and with recent elections, Dilke did very little personal campaigning outside of his Chelsea seat and instead the bulk of Liberal electioneering was done by Dilke’s acolytes, most notably Lloyd George in Wales, Churchill in Scotland, Dillon in Ireland and Austen Chamberlain (assisted, when he was able to, by his father) in the Midlands. While this inevitably lead to a degree of difference between the Liberal message in different parts of the county – famously, in a speech in Birmingham, Chamberlain claimed that the Liberals would immediately move to have a devolved English assembly in the city, which earned him a private rebuke from Dilke – but nothing that appeared to have had a consequential impact on the election. The informal electoral pact with Labour was dissolved, although local Liberal parties did not run serious candidates in seats Labour already held (mostly because of their moribund local organisations).

The Liberals’ laid back attitude may have had something to do with the disunity in the Conservative party. While Liberal splits over trade had largely been settled by 1900 (and before then had often taken place under the cover of debates about Ireland in the 1880s), for the Conservatives they were now out in full force. The pro-tariff wing of the party – largely the most strongly imperialist wings or those most close to the landed interest – saw the benefits of protectionism for agricultural products and closer unity within the Empire. On the other hand, the free trade wing argued that tariff reductions would lower prices, enable the government to scrap the Liberal food subsidies and save money. Many of the free trade Tories also argued for a closer alliance with the French and Americans (perhaps even joining the Triple Entente). While the Conservative manifesto wasn’t as comically contradictory as it had been in 1905, it still failed to paper over the party’s divisions.

In the end, the Liberals lost 76 seats, of which 11 were to Labour (who ran an efficient campaign in their urban targets). While this would have been considered an election-losing result in almost any other circumstance, in the context of the 1904-05 these loses could simply be written off as, in Churchill’s famous words, “natural wastage.” No ministers lost their seats and the party could continue to pass its legislative agenda with a comfortable working majority of over 60.

A total gain for the Conservatives of nearly 70 could also, on most nights, be regarded as a great result. But here it only caused the party to fall further into recrimination, partly because it was their second successive defeat and partly because power seemed to now be within reach (if only tenuously). Arthur Balfour resigned from the leadership of the party in February 1911 and it soon fell into a vigorous internal fight between protectionists such as Bonar Law and Walter Long against free-traders, most notably Charles Ritchie and Michael Hicks-Beach. Long would eventually emerge as the leader but he could do so only by promising Ritchie and Hicks-Beach prominent positions in any future government. As Bonar Law privately commented at the time, this promise was easy to make in opposition but hard to keep in government.

However, whatever hopes the Liberals may have had for a few months of smooth government were dashed by tragedy within a month of the election. Dilke, dressing for a dinner with Lloyd George and Churchill in Number 10, died very suddenly of a heart attack in January 1911, meaning that, for the second election in a row, the Liberals were required to replace an election-winner struck down by illness. This time, however, there was less doubt about the outcome, as Lloyd George was confirmed as Prime Minister eleven days after Dilke’s death, making what many assumed to be his natural promotion a few years earlier than planned. With a small reshuffle of the cabinet – the most notable change of which was the promotion of Churchill to the position of Chancellor – Lloyd George prepared to govern.

Last edited:

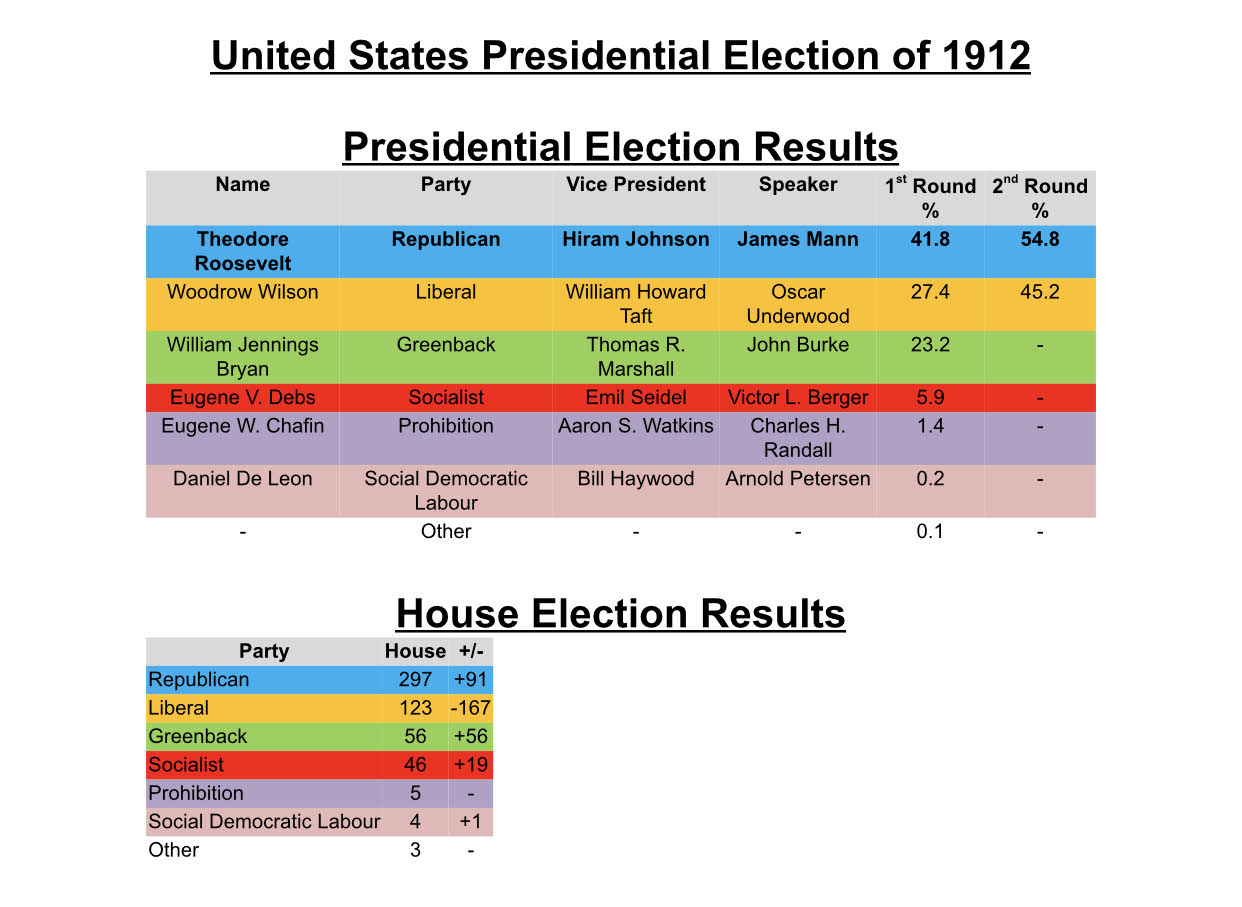

1912 US Presidential Election

Now for something completely different. I've previously said that pretty much every other country ITTL is meaningfully the same as IOTL but with a few exceptions. It should now be clear that one of these exceptions is the US...

From left to right - Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, William Jennings Bryan, Eugene V. Debs, Eugene W. Chafin and Daniel De Leon

The United States presidential election of 1912 was held on Saturday 2 November 1912 and Saturday 16 November 1912. It was the 32nd quadrennial presidential election in the history of the United States and the 9th to have been held under the rules of the Second American Constitution. It was won by New York Governor and former-Vice President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt defeated a field of seven other candidates, winning 41.8% of the vote in the first round and 54.8% in the run-off, thus foiling President William Jennings Bryan in his bid to become the first president to serve for more than two terms under the Second Constitution. In the House elections held at the same time, the Republicans picked up 91 seats to gain a majority of 31. Roosevelt’s running mates were California Governor Hiram Johnson (as Vice President) and Illinois Representative James Mann (as Speaker).

Backed by all notable factions of his party, Roosevelt, who had served as Vice President from 1901 to 1905 and as Governor of New York from 1908 to 1912, was adopted as the Republican candidate after two rounds of balloting at the Republican National Convention. Displeased with Bryan’s actions as president and the way that he had been sidelined since the Liberals had lost control of the Senate in 1910, Vice President Woodrow Wilson challenged Bryan at the 1912 Liberal National Convention. After Wilson’s conservative allies narrowly prevailed at the convention, Bryan rallied his supporters and launched a new party called the Greenback Party, with himself as the presidential candidate. Meanwhile, the Socialist Party and the Social Democratic Labor Party re-nominated their perennial standard-bearers, Eugene V. Debs and Daniel De Leon, respectively. The Prohibition Party nominated Arizona lawyer Eugene W. Chafin.

The election was a bitter and divisive one, mainly contested between the frontrunners of Roosevelt, Wilson and Bryan. Roosevelt’s platform called for an eight-hour workday, female emancipation and a stronger federal role in the economy. Wilson called for tariff reductions, cuts to social insurance programs and banking reform (although he did not call for a return to the gold standard, as he had done as recently as 1907). Bryan ran on a defence of his two terms as president and attempted to portray Wilson as corrupt and a betrayer of Liberal principles. Debs and De Leon claimed that the main three candidates were largely financed by trusts and corrupt business interests while Chafin and his running mates urged voters to help the Prohibitionists hold the balance of power in the new House.

The Republicans skillfully exploited the split between the Liberals and the Greenbacks, winning over former Bryan voters with their progressive policies and reassuring so-called ‘Bourbon’ Liberals through Roosevelt’s personal charm. His 41.8% in the first round was the highest by any first-round candidate since Abraham Lincoln in the 1884 election and he convincingly won the run-off against Wilson by convincing Greenback voters to come over to him. The Socialist result of 5.9% in the presidential election and nearly 50 seats in the house represents, to date, the electoral high point of their party.

The split in the Liberal Party is believed to have been a major factor in the Liberals’ losses in the election, which included not only losing the Presidency but also 167 seats in the House to all of the Republicans, Greenbacks, Socialists and Social Democratic Labor Party. But it is not clear exactly how big a cause this was. Some candidates stood calling for a reunification of the Liberals and the Greenbacks, others appear to have backed both Wilson and Bryan and some campaigned as so-called 'Liberal Greenbacks.' Few sources are able to agree on exact numbers, and even in the contemporary records held by the two parties, some House candidates were claimed for both sides. Furthermore, many analysts at the time believed that the popular mood had turned against Bryan, suggesting that a Republican win could have occurred in any event. By one estimate, there were 29 seats where Greenbacks and Liberals stood against one another. This is thought to have cost them at least 14 seats, 10 of them to the Republicans, so in theory a reunited Liberal Party would have been much closer to the Republicans in the House and might even have won the Presidency (Wilson’s and Bryan’s combined vote total in the first round was 50.6%). However, in reality the two factions were on poor terms and Bryan was hoping for cooperation between the Greenbacks and the Republicans in the House (and possibly even a cabinet position for himself).

* * *

From left to right - Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, William Jennings Bryan, Eugene V. Debs, Eugene W. Chafin and Daniel De Leon

The United States presidential election of 1912 was held on Saturday 2 November 1912 and Saturday 16 November 1912. It was the 32nd quadrennial presidential election in the history of the United States and the 9th to have been held under the rules of the Second American Constitution. It was won by New York Governor and former-Vice President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt defeated a field of seven other candidates, winning 41.8% of the vote in the first round and 54.8% in the run-off, thus foiling President William Jennings Bryan in his bid to become the first president to serve for more than two terms under the Second Constitution. In the House elections held at the same time, the Republicans picked up 91 seats to gain a majority of 31. Roosevelt’s running mates were California Governor Hiram Johnson (as Vice President) and Illinois Representative James Mann (as Speaker).

Backed by all notable factions of his party, Roosevelt, who had served as Vice President from 1901 to 1905 and as Governor of New York from 1908 to 1912, was adopted as the Republican candidate after two rounds of balloting at the Republican National Convention. Displeased with Bryan’s actions as president and the way that he had been sidelined since the Liberals had lost control of the Senate in 1910, Vice President Woodrow Wilson challenged Bryan at the 1912 Liberal National Convention. After Wilson’s conservative allies narrowly prevailed at the convention, Bryan rallied his supporters and launched a new party called the Greenback Party, with himself as the presidential candidate. Meanwhile, the Socialist Party and the Social Democratic Labor Party re-nominated their perennial standard-bearers, Eugene V. Debs and Daniel De Leon, respectively. The Prohibition Party nominated Arizona lawyer Eugene W. Chafin.

The election was a bitter and divisive one, mainly contested between the frontrunners of Roosevelt, Wilson and Bryan. Roosevelt’s platform called for an eight-hour workday, female emancipation and a stronger federal role in the economy. Wilson called for tariff reductions, cuts to social insurance programs and banking reform (although he did not call for a return to the gold standard, as he had done as recently as 1907). Bryan ran on a defence of his two terms as president and attempted to portray Wilson as corrupt and a betrayer of Liberal principles. Debs and De Leon claimed that the main three candidates were largely financed by trusts and corrupt business interests while Chafin and his running mates urged voters to help the Prohibitionists hold the balance of power in the new House.

The Republicans skillfully exploited the split between the Liberals and the Greenbacks, winning over former Bryan voters with their progressive policies and reassuring so-called ‘Bourbon’ Liberals through Roosevelt’s personal charm. His 41.8% in the first round was the highest by any first-round candidate since Abraham Lincoln in the 1884 election and he convincingly won the run-off against Wilson by convincing Greenback voters to come over to him. The Socialist result of 5.9% in the presidential election and nearly 50 seats in the house represents, to date, the electoral high point of their party.

The split in the Liberal Party is believed to have been a major factor in the Liberals’ losses in the election, which included not only losing the Presidency but also 167 seats in the House to all of the Republicans, Greenbacks, Socialists and Social Democratic Labor Party. But it is not clear exactly how big a cause this was. Some candidates stood calling for a reunification of the Liberals and the Greenbacks, others appear to have backed both Wilson and Bryan and some campaigned as so-called 'Liberal Greenbacks.' Few sources are able to agree on exact numbers, and even in the contemporary records held by the two parties, some House candidates were claimed for both sides. Furthermore, many analysts at the time believed that the popular mood had turned against Bryan, suggesting that a Republican win could have occurred in any event. By one estimate, there were 29 seats where Greenbacks and Liberals stood against one another. This is thought to have cost them at least 14 seats, 10 of them to the Republicans, so in theory a reunited Liberal Party would have been much closer to the Republicans in the House and might even have won the Presidency (Wilson’s and Bryan’s combined vote total in the first round was 50.6%). However, in reality the two factions were on poor terms and Bryan was hoping for cooperation between the Greenbacks and the Republicans in the House (and possibly even a cabinet position for himself).

Last edited:

I'm tempted to go for a mixed member-proportional system whereby each person gets two votes, one for a candidate in normal FPTP (making up maybe 75% of MPs) and one for a party to be allocated along a party list basis (the other 25%). That sounds to me like the sort of odd little compromise the British constitution would throw up but I've not firmly decided - we're probably at least a decade away from that in any event.

It's entirely not alien to Britain - both Scotland and Wales use a form of MMP for their devolved elections, and a variant of this (called AV+) was proposed for Westminster elections. That's exactly the really wonky sort of compromise the British political system can manifest.

It's entirely not alien to Britain - both Scotland and Wales use a form of MMP for their devolved elections, and a variant of this (called AV+) was proposed for Westminster elections. That's exactly the really wonky sort of compromise the British political system can manifest.

Yeah. I also happen to think it's a pretty elegant solution to reconciling the question of linking an MP to their constituency and creating majoritarian government while also creating an element of proportionality.

Yeah. I also happen to think it's a pretty elegant solution to reconciling the question of linking an MP to their constituency and creating majoritarian government while also creating an element of proportionality.

Personally, I dislike MMP, because it is a such a mishmash. I especially dislike the system Wales uses, because it is not proportional - it has 2/3 constituencies and 1/3 regional top-up, rather than 50:50.

I would prefer a strictly proportional system. There is nothing that prevents multiple MPs having a constituency link, and such constituencies would be built on far more "natural" communities, instead of arbitrary slices of cities or rural constituencies that are designed to fit a specific amount of population. Indeed, the "constituency link" is a relatively recent thing for MPs in the UK.

Personally, I dislike MMP, because it is a such a mishmash. I especially dislike the system Wales uses, because it is not proportional - it has 2/3 constituencies and 1/3 regional top-up, rather than 50:50.

I would prefer a strictly proportional system. There is nothing that prevents multiple MPs having a constituency link, and such constituencies would be built on far more "natural" communities, instead of arbitrary slices of cities or rural constituencies that are designed to fit a specific amount of population. Indeed, the "constituency link" is a relatively recent thing for MPs in the UK.

Sure, I don't really disagree with that (although I do think it's nice to have somebody to complain to about stuff in my local area). But I would say that this is one of those moments when I think "is this plausible?" rather than just going for outright wish fulfillment and I don't think it's plausible for a British government to leap straight from FPTP to PR. That's not to say that, after a few decades of MMP, the feeling won't be "well this has worked alright, let's go the whole hog."

Threadmarks

View all 190 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Alexander Ministry (2024-2025) Miliband Ministry (2025-2026) Western Canada Independence Referendum, 2024 Western Australia Independence Referendum, 2027 Second Yugoslav War (2009-2029) Stewart Ministry (2026-2031) Commonwealth Election of 2031 World Map, 31 December 2030

Share: