Chapter 6: Lee Takes Command (Part 2)

JJohnson

Banned

Battle of Fredericksburg

Jackson recognized the defensive position of the heights left of the city, but if the Federals could position their artillery on Stafford Heights, counterattack and pursuit would be made impossible, and the Federals would be protected on both flanks by the river, and it would be impracticable to maneuver against Burnside's most vulnerable point, his supply line. If defeated, he could easily withdraw a dozen miles to Aquia Creek before the Confederates could cut the line and isolate his army. Jackson wanted to attack at the North Anna River, where they would have a long retreat, and could easily be smashed along the 37-miles back to Aquia Creek. Lee overruled him, for the fourth time. Fredericksburg would gain him a victory, but little more; Jackson moved into position loyally as was his duty.

Pontoon bridges, ready for deployment.

Union engineers began to assemble six pontoon bridges (similar to those pictured above) before dawn, December 11, two just north of the center of town, the third at the southern end of town, and three farther south, near the meeting of Deep Run and the Rappahanock.

Union pontoon bridges at Franklin Crossing, allowing the Union across the river.

Marye's House, Confederate HQ

The engineers constructing the bridge directly across the city came under fire from Confederate sharpshooters, primarily from Brig. Gen. William Barksdale's Mississippi brigade, in command of town defenses. Union artillery attempted to dislodge the sharpshooters, but their positions in the cellars of houses in town rendered the fire from 150 guns mostly ineffective.

Eventually, Brig. Gen. Henry Hunt, Burnside's artlilery commander, convinced him to send infantry landing parties over in the pontoon boats to establish and secure a small bridgehead and take care of the sharpshooters. Col. Norman Hall volunteered his brigade for this assignment. Burnside suddenly became reluctant, lamenting to Hall in front of his mean that "the effort meant death to most of those who should undertake the voyage."

When his men responded to Hall's request with three cheers, Burnside relented. At 3 PM, the Union artillery began their bombardment to cover their landing, with 135 infantrymen from the 17th Michigan and 19th Massachusetts crowding into the small boats, and the 20th Massachusetts following shortly afterwards. They crossed successfully and spread out in a skirmish line to clear the sharpshooters. Although some of the Confederates surrendered, fighting went street by street through the town as the engineers completed the bridges. Sumner's Right Grand Division began crossing about 4:30 PM, but the bulk of his men didn't cross till the 12th of December. Hooker's Center Grand Division crossed on December 13th, using both the northern and southern bridges.

The clearing of the city's buildings by Sumner's Union infantry and by artillery fire from across the river began the first major urban combat of the war. Union gunners sent out more than 5,000 shells against the town, and the ridges to the west. By nightfall, four brigades of Union troops occupied the town, which they looted with a fury that had not been seen in the war up to that point, and would continue throughout the Union war effort, repeated in every single town they occupied till war's end.

This behavior enraged Lee, who compared their depredations with those of the ancient Vandals. The destruction also angered the Confederate troops, many of whom were native Virginians. Many on the Union side were also shocked by the destruction inflicted on Fredericksburg. Civilian casualties were fortunately low, given the widespread violence.

River crossings south of the city by Franklin's Left Grand Division were much less eventful. Both bridges were completed by 11 AM December 11th, while five batteries of Union artillery suppressed most sniper fire against the engineers. Franklin was ordered at 4PM to cross his entire command, but only a single brigade was sent out before dark. Crossings resumed at dawn, and were completed by 1 PM on the 12th. Early on the 13th, Jackson recalled his divisions under Jubal Early and D.H. Hill from down river positions to join his main defensive lines south of the city.

Burnside's verbal instructions given on December 12th outlined a main attack by Franklin, supported by Hooker on the southern flank, while Sumner made a secondary attack on the northern Flank. His actual orders on December 13th were vague and confusing to his subordinates. At 5 PM on December 12th, he made a cursory inspection of his southern flank, where Franklin and his subordinates pressed him to give them definite orders for the morning attack by the grand division, so they would have adequate time to position their forces overnight. However, Burnside tarried and the order didn't reach Franklin till 7:15 to 7:45 AM. when it arrived, it wasn't what Franklin expected.

Rather than ordering an attack by the entire grand division of almost 60,000 men, Franklin was instead to keep his men in position, and send "a division at least" to seize the high ground (Prospect Hill) around Hamilton's Crossing; Sumner was to send one division through the city and up Telegraph Road, and both flanks were to be prepared to commit their entire commands.

Burnside was apparently expecting those weak attacks to intimidate Lee, causing him to withdraw. Franklin, who originally advocated a vigorous assault, chose to interpret Burnside's order very conservatively. Brig. Gen. James Hardie, who delivered the order, did not ensure that Burnside's intentions were understood by Franklin. Map inaccuracies concerning the road network made his intentions unclear, and his choice of the verb "seize" was less forceful at the time than the order to "carry" the heights.

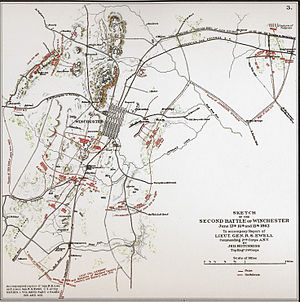

Overview of the battle

The day of the 13th began cold and overcast. A dense fog blanketed the ground and made it impossible for the two armies to see one another. Franklin ordered his I Corps commander, Maj. Gen. John Reynolds, to select one of the divisions for attack; he chose the smallest, the 4500 men of Maj. Gen. George Meade, and assigned Brig. Gen. John Gibbon's division to support Meade's attack.

His reserve division under Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday, was to face south and protect the left flank between Richmond Road and the river. Meade's division began moving out at 8:30 AM, with Gibbon following behind. The fog began lifting about 10:30 AM. The Union started moving parallel to the river, turning right to face Richmond Road, where they began to be hit by enfilading fire from the Virginia Horse Artillery under Major John Pelham. He started with two cannons (12-pounder Napoleon smoothbore, and a rifled Blakely) but continued with only one after the Blakely was disabled by counter-battery fire. J.E.B. Stuart sent word to Pelham that he should feel free to withdraw from his dangerous position at any time, to which Pelham responded, "Tell the General I can hold my ground."

The Iron Brigade (led by Brig. Gen. Solomon Meredith) was sent to deal with the Confederate horse artillery. This action was mainly conducted by the 24th Michigan Infantry, a newly enlisted regiment that had joined the brigade in October. After around an hour, Pelhams ammo began to run low, and he withdrew. General Lee observed this and noted about the 24-year-old, "It is glorious to see such a courage in one so young." The most prominent victim of Pelham's fire was Brig. Gen. George Bayard, a cavalry general who was mortally wounded by a shell while standing in reserve near Franklin's HQ.

General Jackson's main artillery batteries remained silent in the fog while this was happening, but the Union troops soon received direct fire from Prospect Hill, principally five batteries under Lt. Col. Reuben Lindsay Walker's direction, and Meade's attack was stalled about 600 yards from his initial objective for nearly two hours by these combined artillery attacks.

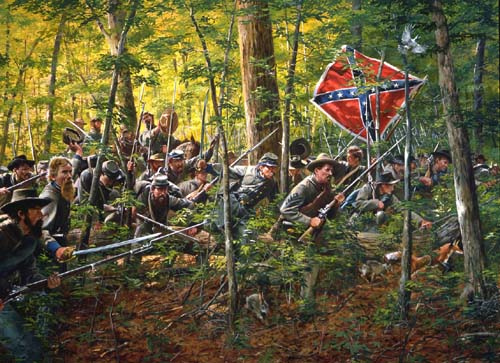

Union artillery fire was lifted as Meade's men moved forward around 1 PM. Jackson's force of around 35,000 remained concealed on the wooded ridge to Meade's front. His formidable defensive line did have an unforeseen flaw. In A.P. Hill's division's line, there was a triangular patch of the woods that extended beyond the railroad; it was swampy and covered with thick underbrush, and the Confederates had left a 600-yard gap there between the brigades of Brig. Gens. James Archer and James Lane.

Brig. Gen. Maxcy Gregg's brigade stood about a quarter mile behind the gap. Meade's 1st brigade (Col. William Sinclair) entered the gap, climbed the railroad embankment, and turned right into the underbrush, striking Lane's brigade in the flank. Following immediately behind, his 3rd Brigade (Brig. Gen. Feger Jackson) turned left and hit Archer's flank. The 2nd Brigade (Col. Albert Magilton) came up in support and intermixed with the leading brigades.

As the gap widened with pressure on the flanks, thousands of Meade's men reached the top of the ridge, and ran into Gregg's brigade. Many of these Confederates had stacked arms while taking cover from Union artillery fire, and weren't expecting to be attacked then, and were killed or captured unarmed. Gregg first mistook the Union soldiers for fleeing Confederates, but he rode back and turned around, rallying his troops. Though partially deaf, he was able to avoid being struck by the bullets, amazingly, though his brigade fought hard, it was totally routed after inflicting a number of casualties, and was no longer an organized unit for the remainder of the day.

James Archer was being pressed hard on his left flank, and sent word for Gregg to reinforce him, unaware his brigade disintegrated. The 19th Georgia's flag was captured by the adjutant of the 7th PA Reserves; it was the only Confederate regimental flag captured and retained by the Army of the Potomac in the battle.

Similar to the 19th, the 65th Georgia's flag is on display in the Georgia Museum of Confederate History, with Curator Angela Gregg, the great-great-great granddaughter of Brigadier General Maxcy Gregg, who fought at Fredericksburg.

14th Tennessee Regimental Flag, currently on display at the Tennessee Confederate Historical Museum.

The Georgians broke ranks and ran. The 14th Tennessee resisted the onslaught for a little while longer before breaking also; a large number of its men were taken prisoner. Archer frantically sent messages to the rear, calling on John Brockenbrough and Edmund Atkinson's brigades for help. With ammunition on both sides running low, hand-to-hand fighting broke out with soldiers stabbing each other with bayonets, and using muskets as clubs. Most of the regimental officers on both sides fell as well; on the Confederate side, the 1st Tennessee going through three commanders in minutes; Meade's 15 regiments lost most of their officers also, although Meade himself survived the battle unscathed, despite having been exposed to heavy artillery fire.

Confederate reserves, namely the divisions of Brig. Gens. Jubal Early and William Taliaferro (pronounced "Toliver"), moved into the fray from behind Gregg's position. Inspired by their attack, regiments from Lane's and Archer's brigades also rallied and formed a new defensive line in the gap. Now Meade's men were receiving fire from three sides and could not withstand it. Feger Jackson attempted to flank a Confederate battery, but after his horse was shot, he began to lead on foot, and then was shot in the head by a volley, and his brigade fell back, leaderless; Col. Joseph Fisher soon replaced Jackson in command.)

To Meade's right, Gibbon's division prepared to move forward at 1 PM. Brig. Gen. Nelson Taylor proposed to Gibbon that they supplement Meade's assault with a bayonet charge against Lane's position. Gibbon told him this would violate his orders, so Taylor's brigade didn't move forward till 1:30 PM. The Union attack didn't have the benefit of a gap to exploit in Confederate lines, nor did the Union soldiers have any wooded cover for their advance, so progress was slow under heavy fire from Lane's brigade and Confederate artillery.

Immediately following Taylor was the brigade of Col. Peter Lyle, and the advance of the two brigades ground to a halt before they reached the railroad. Committing his reserve at 1:45 PM, Gibbon sent forward his brigade under Col. Adrian Root, which moved through the survivors of the first two brigades, but they were brought to a halt soon as well. Eventually some of the Union troops reached the crest of the ridge, and had some success during hand-to-hand fighting. Men on both sides had depleted their ammunition and resorted to bayonets and rifle butts, and even empty rifles with bayonets thrown like javelins, but they were forced to withdraw back across the railroad embankment along with Meade's men to their left.

Gibbon's attack, despite heavy casualties, failed to support Meade's temporary breakthrough, and Gibbon himself got wounded in the attack when a shell fragment struck his right hand. Brig. Gen Nelson Taylor took over command of his division.

During the afternoon, Maj. Gen. George Meade asked to Maj. Gen. John Reynolds, "My God, General Reynolds, did they think my division could whip Lee's whole army?"

On the Confederate side, Gen. Lee watched the carnage unfolding of the Confederate counterattack from the center of his line, remarked, "It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it." His position became known soon after as Lee's Hill.

After the battle, Meade complained some of Gibbon's officers hadn't charged quickly enough, but his main frustration was with Brig. Gen. David Birney, whose division of the III Corps had been designated to support the attack. Birney claimed his men had been subjected to devastating artillery fire as they formed up, he hadn't understood the importance of Meade's attack, and that Reynolds hadn't ordered his division forward.

When Meade galloped to the rear to confront Birney with a string of profanities that in the words of one staff lieutenant, "almost makes the stones creep," he was finally able to order the brigadier forward under his own responsibility, but by this time, it was too late to accomplish any further offensive action.

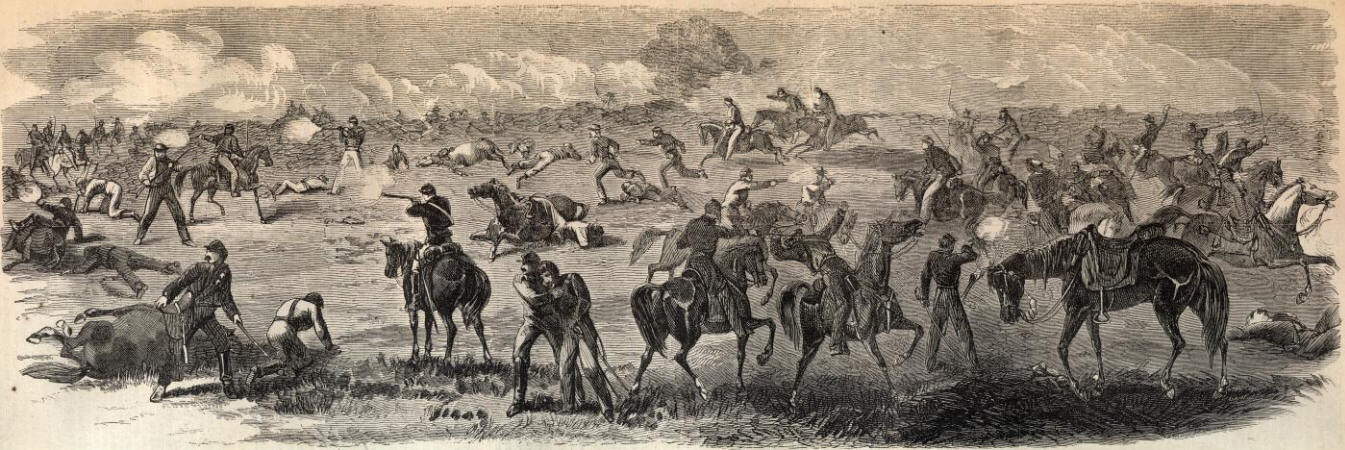

Confederates in Early's division began a counterattack, led initially by Col Edmund Atkinson's Georgia brigade, which inspired men from the brigades of Col Robert Hoke, Brig. Gen. James Archer, and Col. John Brockenbrough to charge forward out of the railroad ditches, driving Meade's men from the woods in a disorderly retreat, followed closely by Gibbon's men. Early's orders to his brigades were to pursue as far as the railroad, but in the chaus, many kept up the pressure over the open fields as far as the old Richmond Road.

Union artillery crews proceeded to unleash a blast of close-range canister shot, firing as fast as they could load their guns. The Confederates were also struck by the leading brigade of Birney's belated advance, commanded by Brig. Gen. J.H. Hobart Ward. Birney followed up with the brigades of Brig. Gens. Hiram Berry and John Robinson, which broke the Confederate advance which had threatened to drive the Union into the river. Confederate Col. Atkinson got hit in the shoulder by canister shot and was abandoned by his own brigade; Union soldiers later found him and took him prisoner. Further Confederate advance was deterred by the arrival of the III Corps division led by Brig. Gen. Daniel Sickles on the right. General Burnside, who was now focusing on his attack on Marye's Heights, was frustrated his left flank attack hadn't achieved the success he assumed earlier in the day. So he ordered Franklin to "advance his right and front," but despite his repeated request, Franklin refused, claiming all his forces were engaged. This wasn't true, as the entire VI Corps of Brig. Gen. Abner Doubleday's division of the I Corps had been mostly idle, suffering just a few casualties from artillery fire while waiting in reserve.

The Confederates withdrew back to the safety of the hills south of town. General "Stonewall" Jackson considered mounting a resumed counterattack, but the impending darkness and the Federal artillery changed his mind. The Union breakthrough had been wasted because Franklin didn't reinforce Meade's success with his roughly 20,000 men standing in reserve, and neither Franklin nor Reynolds took any personal involvement in the battle, and were unavailable to their subordinates at the critical point. Franklin's losses were about 5000 casualties in comparison to Jackson's 3300. Skirmishing and artillery duels continued until dark, but no additional major attacks took place, and the center of the battle moved north to Marye's Heights. Brig. Gen. George Bayard, in command of the cavalry brigade of the VI Corps, was struck in the leg by a shell fragment, and died two days later.

As the fighting south of Fredericksburg died down, the air was filled with the screams of hundreds of wounded men and horses. Dry sage grass around them caught fire and burned many men alive.

Marye's Heights

Over on the northern end of the battlefield, Brig. Gen. William French's division of II Corps prepared to move forward, subjected to Confederate artillery fire descending on the fog-covered city of Fredericksburg. General Burnside's orders to Maj Gen Edwin Sumner, commander of the Right Grand Division, was to send "a division or more" to seize the high ground west of the city, assuming that his assault on the southern end of the Confederate line would be the decisive action of the battle.

The avenue of approach to the Confederates was difficult, mostly open fields, but interrupted by scattered houses, fences, and gardens that would restrict the movement of the battle lines. A canal stood about 200 yards west of the town, crossed by three narrow bridges, which would require the Union troops to funnel themselves into columns before proceeding. About 600 yards west of Fredericksburg was a low ridge called Marye's Heights, rising 40-50 feet above the plain. Though known as Marye's Heights, it was composed of several hills, north to south: Taylor's, Stansbury, Marye's, and Willis Hill. Near the crest of the part of the ridge made of Marye's and Willis Hihll, a narrow lane in a slight cut, the Telegraph Road, known after the battle as the Sunken Road, was protected by a 4-foot stone wall, enhanced in places with log breastworks and batis, making it a perfect infantry defensive position.

Confederate Major General Lafayette McLaws initially had about 2000 men on the front line of Marye's Heights, and there were an additional 7000 men in reserve on the crest and behind the ridge. Massed artillery also provided almost uninterrupted coverage of the plain below. General Longstreet was assured by his artillery commander, Lt Col Edward P Alexander, "General, we cover that ground now so well that we will comb it as with a fine-tooth comb. A chicken could not live on that field when we open on it."

The Confederate troops behind the stone wall

The fog lifted from the town about 10 AM, and Sumner gave his order to advance an hour later. French's brigade under Brig. Gen. Nathan Kimball began to move around noon. They advanced slowly through heavy artillery fire, crossed the canal in columns over the narrow bridges, and formed in line, with fixed bayonets, behind the protection of a shallow bluff. In perfect line of battle, they advanced up the muddy slope until they were cut down about 125 yards from the stone wall by repeated rifle volleys.

Some soldiers were able to get as close as 40 yards, but having suffered severe casualties from both artillery and infantry fire, the survivors clung to the ground. Kimball himself was severely wounded during the assault, and his brigade suffered 25% casualties. French's brigades under Col John Andrews and Col Oliver Palmer followed, with casualty rates of about 50%.

Sumner's original order called for the division of Brig. Gen. Winfield Hancock to support French and Hancock sent forward his brigade under Col Samuel Zook, behind Palmer's. They met a similar fate. Next was his Irish Brigade under Brig. Gen. Thomas Meagher.

Union Irish Brigade, which participated in the fighting at Marye's Heights.

Irish Regiment Flag

The original flag flown at Fredericksburg hangs in the Museum of the Confederacy

First Scottish Regiment Flag

This is the flag flown at Fredericksburg, not the Second Scottish Regiment Flag, which was introduced in 1864.

By coincidence, they attacked the area defended by fellow Irishmen of Col. Robert McMillan's 24th GA Infantry. One Confederate who spotted the green regimental flags approaching cried out, "Oh, God what a pity! Here comes Meagher's fellows." But McMillan exhorted his troops, "Give it to them now, boys! Now's the time! Give it to them!"

Hancock's final brigade was led by Brig. Gen. John Caldwell. Leading his two regiments on the left, Col Nelson Miles suggested to Caldwell that the practice of marching in formation, firing, and stopping to reload made the Union soldiers easy targets, and that a concerted bayonet charge might be more effective in carrying the works. Caldwell denied permission; Miles was struck by a bullet in the throat as he led his men to within 40 yards of the wall, where they were pinned down as their predecessors had been. Caldwell himself was soon struck by two bullets and put out of the action.

Union Assault on Marye's Heights

The commander of the II Corps, Maj. Gen. Darius Couch, was dismayed at the carnage wrought upon his two divisions in the hour of fighting, and like Col. Miles, realized the tactics weren't working. He first considered a massive bayonet charge, but as he surveyed the front, he quickly realized French's and Hancock's divisions were in no shape to move forward again.

He planned for his final division, under Maj. Gen. Oliver Howard, to swing to the right and attempt to envelop the Confederate left, but after receiving urgent requests for help from French and Hancock, he sent Howard's men over and around the fallen troops instead. The brigade of Col. Joshua Owen went in first, reinforced by Col. Norman Hall's brigade, and then two regiments of Brig. Gen. Alfred Sully's brigade. The other corps in Sumner's grand division was the IX Corps, and he sent in one of its divisions under Brig. Gen. Samuel Sturgis. After two hours of desperate fighting, four Union divisions had failed in the mission Burnside originally assigned to one. Their casualties were heavy - II Corps lost 4398 and Sturgis's division 1033.

While the Union army paused, Longstreet reinforced his line so that there were four ranks of infantrymen behind the stone wall. Brig. Gen. Thomas Cobb of Georgia, who commanded the key sector of the line was mortally wounded by an exploding artillery shell, and was replaced by Brig. Gen. Joseph Kershaw. General Lee expressed some concern to Longstreet about the massing troops breaking the line, but Longstreet assured him, "General, if you put every man on the other side of the Potomac on that field to approach me over the same line, and give me plenty of ammunition, I will kill them all before they reach my line."

By midafternoon, Burnside had failed on both flanks to make progress against the Confederates. Rather than reconsidering his approach in the face of such heavy casualties, he decided to continue on the same path. He sent orders to Franklin to renew the assault on the left (orders he ignored), and ordered his Center Grand Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, to cross the Rappahannock into Fredericksburg and continue the attack on Marye's Heights. Hooker performed personal reconnaissance (something neither Burnside nor Sumner did) and returned to Burnside's HQ to advise against the attack.

Brig Gen. Daniel Butterfield, commanding Hooker's V Corps sent his division under Brig. Gen. Charles Griffin to relieve Sturgis's men while waiting for Hooker to return from his conference with Burnside. By this time, Maj. Gen. George Pickett's Confederate division and one of Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood's brigades had marched north to reinforce Marye's Heights. Griffin smashed his three brigades against the Confederate position, one by one. Also concerned about Sturgis, Couch sent the six guns of Capt. John Hazard's Battery B, 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery, to within 150 yards of the Confederate line. They were hit hard by Confederate sharpshooters and artillery fire and provided no effective relief to Sturgis.

A soldier in Hancock's division reported movement in the Confederate line, leading some to believe they might be retreating. Despite the unlikeliness of that belief, the V Corps division of Brig. Gen. Andrew Humphreys was ordered to attack and capitalize on the situation. Humphreys led his first brigade on horseback, with his men moving over and around fallen troops with fixed bayonets and unloaded rifles; some of the fallen men clutched the passing pant legs, urging their comrades not to go forward, causing the brigade to become disorganized in their advance. The charge reached to within 50 yards before being cut down by rifle fire. Brig. Gen. George Sykes was ordered to move forward with his V Corps regular army division to support Humphreys's retreat, but his men were caught in a crossfire and pinned down.

By 4 PM, Hooker returned from his meeting with Burnside, having failed to convince the general to abandon his attacks. While Humphreys was still attacking, Hooker reluctantly ordered the IX Corps division of Brig. Gen. George Getty to attack as well, but this time to the leftmost portion of Marye's Heights, called Willis Hill. Col. Rush Hawkins's Brigade, followed by Col Edward Harland's brigade, moved along an unfinished railroad line just north of Hazel Run, approaching close to the Confederate line without detection in the gathering twilight, but they were eventually detected, fired on, and repulsed.

Seven Union divisions had been sent in, generally one brigade at a time, for a total of fourteen separate charges, all of which failed, costing between 7,000 and 9,000 casualties. Confederate losses at Marye's Heights totaled around 1200. The setting sun and the please of Burnside's subordinates were enough to put an end to the attacks. Longstreet later wrote, "The charges had been desperate and bloody, but utterly hopeless." Thousands of Union soldiers spent the cold December night on the fields leading to the heights, unable to move or assist the wounded because of Confederate fire. That night, Burnside attempted to blame his subordinates for the disastrous attacks, but they argued it was entirely his fault and none other's.

During a dinner meeting in the evening of December 13, Union General Burnside dramatically announced he would personally lead his old IX Corps in one final attack on Marye's Heights, but his generals talked him out of it the next morning. The armies remained in position throughout the day on December 14th. That afternoon, Burnside asked Lee for a truce to attend to his wounded, which Lee graciously granted. Both sides removed their wounded, and the next day, the Federal forces retreated across the river, and the campaign came to an end.

Union casualties were 14,199, with 2,384 killed, the rest wounded (9600) or captured/missing. They lost two generals - Brig. Gens. George Bayard and Conrad Jackson. The Confederates lost 5180 (550 killed, 4108 wounded, the rest captured/missing). Brig. Gens. Maxcy Gregg and T.R.R. Cobb were wounded but would recover.

Angel of Marye's Heights, Sgt. Richard Rowland Kirkland

One of the more courageous acts of the entire war, and a sample of the humanity sometimes lacking in war, was the story of Confederate Sergeant Richard Rowland, Kirkland, of Company G, 2nd South Carolina Volunteer Infantry. He had been stationed at a stone wall by the sunken road below Marye's Heights.

The Stone Wall and Sunken Road, 2010;

Sharpsburg Confederate Memorial Battlefield Park

He had a close-up view to the suffering, and like so many others was appalled at the cries for help of the Union wounded throughout the cold winter night of December 13, 1862. After getting the permission of his commander, Brig. Gen. Joseph Kershaw, Kirkland gathered canteens, and in broad daylight, without the benefit of a recognized ceasefire or flag of truce, provided water to numerous Union wounded lying on the field of battle, easing their suffering and cries.

Memorial Statue of Sgt. Kirkland, a copy of the original at Fredericksburg Battlefield Park.

Flat Rock, South Carolina

Union soldiers held their fire, as it was obvious what his intent was. Kirkland was nicknamed the "Angel of Marye's Heights" for his actions, and is memorialized with a statue by Anton van der Velden at the Fredericksburg Confederate Memorial Battlefield Park where he carried out his actions, and later copied in his home town of Flat Rock, South Carolina.

On the night of December 14, the Aurora Borealis made an appearance, unusually enough for the latitude, possibly caused by a solar flare. One witness described it as "the wonderful spectacle of the Aurora Borealis was seen in the Gulf States. The whole sky was a ruddy glow as if from an enormous conflagration, but marked by the darting rays peculiar to the Northern light."

The remarkable event was noted in the diaries and letters of many of the Union and Confederate soldiers at Fredericksburg, such as John W. Thompson, Jr, who wrote: "Louisiana sent those famous cosmopolitan Zouaves called the Louisiana Tigers, and there were Florida troops who, undismayed in fire, stampeded the night after Fredericksburg, when the Aurora Borealis snapped and crackled over that field of the frozen dead hard by the Rappahannock ..."

Some of the senior Confederate generals took it as a sign from heaven of the blessing of their cause; some Union troops took it as a divine shield of protection over the Confederates.

Lull and Withdrawal

Union View of the Confederates, one of the rare times they photographed their opponents during the War for Southern Independence

General Burnside and the Federal troops had abandoned the once beautiful city of Fredericksburg. A chilling rainstorm drenched the night countryside as the Federal troops retreated across the Rappahannock. After they left, General Jackson looked over the still bloody battlefield and declared, "I did not think a little red earth would have frightened them. I am sorry that they are gone." By the 16th, Confederate troops reoccupied Fredericksburg. Later as Jackson and his staff rode through the city their anger was aroused by the extent of the ruthless vandalism. A staff officer commented on how thoroughly the Federals had taken the town apart and asked, "What can we do?" "Do?" replied Jackson, "Why, shoot them!"

On Princess Anne Street General Jackson is directing the refortification of the city and setting up new defenses, as a horse-drawn artillery piece rushes by, pulled by a fine team of Morgan horses. Soon new orders will call Jackson away from the city he helped to defend so successfully.

The people of Fredericksburg welcomed the Confederates as liberators from the Union looters, and the troops were refreshed, as they helped repair and clean the city.

Aftermath of the Battle

The South was jubilant over their victory. The Richmond Examiner described it as "a stunning defeat to the invader, a splendid victory to the defender of the sacred soil." General Lee, normally reserved, was described by the Charleston Mercury as "jubilant, almost off-balance, and seemingly desirous of embracing everyone who calls on him." The newspaper also exclaimed that, "General Lee knows his business and the army has yet known no such word as fail."

Reactions were the opposite in the North, and both the Army and President Lincoln came under strong attacks from both politicians and the press. The Cincinnati Commercial wrote, "It can hardly be in human nature for men to show more valor or generals to manifest less judgment, than were perceptible on our side that day." Senator Zachariah Chandler, a radial Republican, wrote, "The President is a weak man, too weak for the occasion, and those fool or traitor generals are wasting time and yet more precious blood in indecisive battles and delays." Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin visited the White House after a trip to the battlefield. He told the President, "It was not a battle, it was butchery."

Curtin reported that the President was "heart-broken at the recital, and soon reached a state of nervous excitement bordering on insanity." Lincoln himself wrote, "If there is a worse place than hell, I am in it." Burnside was relieved of command a month later, following an unsuccessful attempt to purge some of his subordinates from the Army, and the humiliating failure of his Mud March in January.

Christmas in Fredericksburg

Time was short for General Jackson's Stonewall Brigade; final preparations were underway. He had received orders from General Lee to move his corps east, from the Shenandoah towards the Rappahannock River. The Federal army under the command of General Burnside was gathering in great numbers across the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg in an attempt to sweep around Lee's eastern flank and attack Richmond.

Jackson's corps numbered over 38,000 soldiers, the largest command he had ever had. Among these troops were his old reliable, tried and true, Stonewall Brigade, also referred to informally as "Virginia's First Brigade." Organized and trained personally by Jackson at Harper's Ferry in April 1861, the brigade would distinguish itself at the Battle of First Manassas, and become one of the most famous combat units in the war.

Snow lay on the ground in Winchester at the Frederick County Courthouse as new volunteers were organized and drilled for their march to meet the enemy. A young soldier was given a Christmas gift made by his sweetheart. Like so many couples, they did not know what the future held. The town was grateful to the Confederate soldiers for freeing them from the Union troops who had only recently been there.

A Winchester resident watching the men pass through the town remarked how poor looking the soldiers were. "They were very destitute, many without shoes, and all without overcoats or gloves, although the weather was freezing. Their poor hands looked so red and cold holding their muskets in the biting wind....They did not, however look dejected, but went their way right joyfully."

While foreign shipments came in, and cotton went out, just at reduced levels from prewar standards, supply issues within the Confederacy meant that sometimes soldiers were not always equipped as well as their Union counterparts. Before the next battle, these new recruits would have new boots to cover their feet from the cold, and new overcoats woven in the United Kingdom. Still, the British had not recognized the Confederates, nor had they broken their neutrality of trading with both North and South, but refused to trade munitions with either side.

Jackson recognized the defensive position of the heights left of the city, but if the Federals could position their artillery on Stafford Heights, counterattack and pursuit would be made impossible, and the Federals would be protected on both flanks by the river, and it would be impracticable to maneuver against Burnside's most vulnerable point, his supply line. If defeated, he could easily withdraw a dozen miles to Aquia Creek before the Confederates could cut the line and isolate his army. Jackson wanted to attack at the North Anna River, where they would have a long retreat, and could easily be smashed along the 37-miles back to Aquia Creek. Lee overruled him, for the fourth time. Fredericksburg would gain him a victory, but little more; Jackson moved into position loyally as was his duty.

Pontoon bridges, ready for deployment.

Union engineers began to assemble six pontoon bridges (similar to those pictured above) before dawn, December 11, two just north of the center of town, the third at the southern end of town, and three farther south, near the meeting of Deep Run and the Rappahanock.

Union pontoon bridges at Franklin Crossing, allowing the Union across the river.

Marye's House, Confederate HQ

The engineers constructing the bridge directly across the city came under fire from Confederate sharpshooters, primarily from Brig. Gen. William Barksdale's Mississippi brigade, in command of town defenses. Union artillery attempted to dislodge the sharpshooters, but their positions in the cellars of houses in town rendered the fire from 150 guns mostly ineffective.

Eventually, Brig. Gen. Henry Hunt, Burnside's artlilery commander, convinced him to send infantry landing parties over in the pontoon boats to establish and secure a small bridgehead and take care of the sharpshooters. Col. Norman Hall volunteered his brigade for this assignment. Burnside suddenly became reluctant, lamenting to Hall in front of his mean that "the effort meant death to most of those who should undertake the voyage."

When his men responded to Hall's request with three cheers, Burnside relented. At 3 PM, the Union artillery began their bombardment to cover their landing, with 135 infantrymen from the 17th Michigan and 19th Massachusetts crowding into the small boats, and the 20th Massachusetts following shortly afterwards. They crossed successfully and spread out in a skirmish line to clear the sharpshooters. Although some of the Confederates surrendered, fighting went street by street through the town as the engineers completed the bridges. Sumner's Right Grand Division began crossing about 4:30 PM, but the bulk of his men didn't cross till the 12th of December. Hooker's Center Grand Division crossed on December 13th, using both the northern and southern bridges.

The clearing of the city's buildings by Sumner's Union infantry and by artillery fire from across the river began the first major urban combat of the war. Union gunners sent out more than 5,000 shells against the town, and the ridges to the west. By nightfall, four brigades of Union troops occupied the town, which they looted with a fury that had not been seen in the war up to that point, and would continue throughout the Union war effort, repeated in every single town they occupied till war's end.

This behavior enraged Lee, who compared their depredations with those of the ancient Vandals. The destruction also angered the Confederate troops, many of whom were native Virginians. Many on the Union side were also shocked by the destruction inflicted on Fredericksburg. Civilian casualties were fortunately low, given the widespread violence.

River crossings south of the city by Franklin's Left Grand Division were much less eventful. Both bridges were completed by 11 AM December 11th, while five batteries of Union artillery suppressed most sniper fire against the engineers. Franklin was ordered at 4PM to cross his entire command, but only a single brigade was sent out before dark. Crossings resumed at dawn, and were completed by 1 PM on the 12th. Early on the 13th, Jackson recalled his divisions under Jubal Early and D.H. Hill from down river positions to join his main defensive lines south of the city.

Burnside's verbal instructions given on December 12th outlined a main attack by Franklin, supported by Hooker on the southern flank, while Sumner made a secondary attack on the northern Flank. His actual orders on December 13th were vague and confusing to his subordinates. At 5 PM on December 12th, he made a cursory inspection of his southern flank, where Franklin and his subordinates pressed him to give them definite orders for the morning attack by the grand division, so they would have adequate time to position their forces overnight. However, Burnside tarried and the order didn't reach Franklin till 7:15 to 7:45 AM. when it arrived, it wasn't what Franklin expected.

Rather than ordering an attack by the entire grand division of almost 60,000 men, Franklin was instead to keep his men in position, and send "a division at least" to seize the high ground (Prospect Hill) around Hamilton's Crossing; Sumner was to send one division through the city and up Telegraph Road, and both flanks were to be prepared to commit their entire commands.

Burnside was apparently expecting those weak attacks to intimidate Lee, causing him to withdraw. Franklin, who originally advocated a vigorous assault, chose to interpret Burnside's order very conservatively. Brig. Gen. James Hardie, who delivered the order, did not ensure that Burnside's intentions were understood by Franklin. Map inaccuracies concerning the road network made his intentions unclear, and his choice of the verb "seize" was less forceful at the time than the order to "carry" the heights.

Overview of the battle

The day of the 13th began cold and overcast. A dense fog blanketed the ground and made it impossible for the two armies to see one another. Franklin ordered his I Corps commander, Maj. Gen. John Reynolds, to select one of the divisions for attack; he chose the smallest, the 4500 men of Maj. Gen. George Meade, and assigned Brig. Gen. John Gibbon's division to support Meade's attack.

His reserve division under Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday, was to face south and protect the left flank between Richmond Road and the river. Meade's division began moving out at 8:30 AM, with Gibbon following behind. The fog began lifting about 10:30 AM. The Union started moving parallel to the river, turning right to face Richmond Road, where they began to be hit by enfilading fire from the Virginia Horse Artillery under Major John Pelham. He started with two cannons (12-pounder Napoleon smoothbore, and a rifled Blakely) but continued with only one after the Blakely was disabled by counter-battery fire. J.E.B. Stuart sent word to Pelham that he should feel free to withdraw from his dangerous position at any time, to which Pelham responded, "Tell the General I can hold my ground."

The Iron Brigade (led by Brig. Gen. Solomon Meredith) was sent to deal with the Confederate horse artillery. This action was mainly conducted by the 24th Michigan Infantry, a newly enlisted regiment that had joined the brigade in October. After around an hour, Pelhams ammo began to run low, and he withdrew. General Lee observed this and noted about the 24-year-old, "It is glorious to see such a courage in one so young." The most prominent victim of Pelham's fire was Brig. Gen. George Bayard, a cavalry general who was mortally wounded by a shell while standing in reserve near Franklin's HQ.

General Jackson's main artillery batteries remained silent in the fog while this was happening, but the Union troops soon received direct fire from Prospect Hill, principally five batteries under Lt. Col. Reuben Lindsay Walker's direction, and Meade's attack was stalled about 600 yards from his initial objective for nearly two hours by these combined artillery attacks.

Union artillery fire was lifted as Meade's men moved forward around 1 PM. Jackson's force of around 35,000 remained concealed on the wooded ridge to Meade's front. His formidable defensive line did have an unforeseen flaw. In A.P. Hill's division's line, there was a triangular patch of the woods that extended beyond the railroad; it was swampy and covered with thick underbrush, and the Confederates had left a 600-yard gap there between the brigades of Brig. Gens. James Archer and James Lane.

Brig. Gen. Maxcy Gregg's brigade stood about a quarter mile behind the gap. Meade's 1st brigade (Col. William Sinclair) entered the gap, climbed the railroad embankment, and turned right into the underbrush, striking Lane's brigade in the flank. Following immediately behind, his 3rd Brigade (Brig. Gen. Feger Jackson) turned left and hit Archer's flank. The 2nd Brigade (Col. Albert Magilton) came up in support and intermixed with the leading brigades.

As the gap widened with pressure on the flanks, thousands of Meade's men reached the top of the ridge, and ran into Gregg's brigade. Many of these Confederates had stacked arms while taking cover from Union artillery fire, and weren't expecting to be attacked then, and were killed or captured unarmed. Gregg first mistook the Union soldiers for fleeing Confederates, but he rode back and turned around, rallying his troops. Though partially deaf, he was able to avoid being struck by the bullets, amazingly, though his brigade fought hard, it was totally routed after inflicting a number of casualties, and was no longer an organized unit for the remainder of the day.

James Archer was being pressed hard on his left flank, and sent word for Gregg to reinforce him, unaware his brigade disintegrated. The 19th Georgia's flag was captured by the adjutant of the 7th PA Reserves; it was the only Confederate regimental flag captured and retained by the Army of the Potomac in the battle.

Similar to the 19th, the 65th Georgia's flag is on display in the Georgia Museum of Confederate History, with Curator Angela Gregg, the great-great-great granddaughter of Brigadier General Maxcy Gregg, who fought at Fredericksburg.

14th Tennessee Regimental Flag, currently on display at the Tennessee Confederate Historical Museum.

The Georgians broke ranks and ran. The 14th Tennessee resisted the onslaught for a little while longer before breaking also; a large number of its men were taken prisoner. Archer frantically sent messages to the rear, calling on John Brockenbrough and Edmund Atkinson's brigades for help. With ammunition on both sides running low, hand-to-hand fighting broke out with soldiers stabbing each other with bayonets, and using muskets as clubs. Most of the regimental officers on both sides fell as well; on the Confederate side, the 1st Tennessee going through three commanders in minutes; Meade's 15 regiments lost most of their officers also, although Meade himself survived the battle unscathed, despite having been exposed to heavy artillery fire.

Confederate reserves, namely the divisions of Brig. Gens. Jubal Early and William Taliaferro (pronounced "Toliver"), moved into the fray from behind Gregg's position. Inspired by their attack, regiments from Lane's and Archer's brigades also rallied and formed a new defensive line in the gap. Now Meade's men were receiving fire from three sides and could not withstand it. Feger Jackson attempted to flank a Confederate battery, but after his horse was shot, he began to lead on foot, and then was shot in the head by a volley, and his brigade fell back, leaderless; Col. Joseph Fisher soon replaced Jackson in command.)

To Meade's right, Gibbon's division prepared to move forward at 1 PM. Brig. Gen. Nelson Taylor proposed to Gibbon that they supplement Meade's assault with a bayonet charge against Lane's position. Gibbon told him this would violate his orders, so Taylor's brigade didn't move forward till 1:30 PM. The Union attack didn't have the benefit of a gap to exploit in Confederate lines, nor did the Union soldiers have any wooded cover for their advance, so progress was slow under heavy fire from Lane's brigade and Confederate artillery.

Immediately following Taylor was the brigade of Col. Peter Lyle, and the advance of the two brigades ground to a halt before they reached the railroad. Committing his reserve at 1:45 PM, Gibbon sent forward his brigade under Col. Adrian Root, which moved through the survivors of the first two brigades, but they were brought to a halt soon as well. Eventually some of the Union troops reached the crest of the ridge, and had some success during hand-to-hand fighting. Men on both sides had depleted their ammunition and resorted to bayonets and rifle butts, and even empty rifles with bayonets thrown like javelins, but they were forced to withdraw back across the railroad embankment along with Meade's men to their left.

Gibbon's attack, despite heavy casualties, failed to support Meade's temporary breakthrough, and Gibbon himself got wounded in the attack when a shell fragment struck his right hand. Brig. Gen Nelson Taylor took over command of his division.

During the afternoon, Maj. Gen. George Meade asked to Maj. Gen. John Reynolds, "My God, General Reynolds, did they think my division could whip Lee's whole army?"

On the Confederate side, Gen. Lee watched the carnage unfolding of the Confederate counterattack from the center of his line, remarked, "It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it." His position became known soon after as Lee's Hill.

After the battle, Meade complained some of Gibbon's officers hadn't charged quickly enough, but his main frustration was with Brig. Gen. David Birney, whose division of the III Corps had been designated to support the attack. Birney claimed his men had been subjected to devastating artillery fire as they formed up, he hadn't understood the importance of Meade's attack, and that Reynolds hadn't ordered his division forward.

When Meade galloped to the rear to confront Birney with a string of profanities that in the words of one staff lieutenant, "almost makes the stones creep," he was finally able to order the brigadier forward under his own responsibility, but by this time, it was too late to accomplish any further offensive action.

Confederates in Early's division began a counterattack, led initially by Col Edmund Atkinson's Georgia brigade, which inspired men from the brigades of Col Robert Hoke, Brig. Gen. James Archer, and Col. John Brockenbrough to charge forward out of the railroad ditches, driving Meade's men from the woods in a disorderly retreat, followed closely by Gibbon's men. Early's orders to his brigades were to pursue as far as the railroad, but in the chaus, many kept up the pressure over the open fields as far as the old Richmond Road.

Union artillery crews proceeded to unleash a blast of close-range canister shot, firing as fast as they could load their guns. The Confederates were also struck by the leading brigade of Birney's belated advance, commanded by Brig. Gen. J.H. Hobart Ward. Birney followed up with the brigades of Brig. Gens. Hiram Berry and John Robinson, which broke the Confederate advance which had threatened to drive the Union into the river. Confederate Col. Atkinson got hit in the shoulder by canister shot and was abandoned by his own brigade; Union soldiers later found him and took him prisoner. Further Confederate advance was deterred by the arrival of the III Corps division led by Brig. Gen. Daniel Sickles on the right. General Burnside, who was now focusing on his attack on Marye's Heights, was frustrated his left flank attack hadn't achieved the success he assumed earlier in the day. So he ordered Franklin to "advance his right and front," but despite his repeated request, Franklin refused, claiming all his forces were engaged. This wasn't true, as the entire VI Corps of Brig. Gen. Abner Doubleday's division of the I Corps had been mostly idle, suffering just a few casualties from artillery fire while waiting in reserve.

The Confederates withdrew back to the safety of the hills south of town. General "Stonewall" Jackson considered mounting a resumed counterattack, but the impending darkness and the Federal artillery changed his mind. The Union breakthrough had been wasted because Franklin didn't reinforce Meade's success with his roughly 20,000 men standing in reserve, and neither Franklin nor Reynolds took any personal involvement in the battle, and were unavailable to their subordinates at the critical point. Franklin's losses were about 5000 casualties in comparison to Jackson's 3300. Skirmishing and artillery duels continued until dark, but no additional major attacks took place, and the center of the battle moved north to Marye's Heights. Brig. Gen. George Bayard, in command of the cavalry brigade of the VI Corps, was struck in the leg by a shell fragment, and died two days later.

As the fighting south of Fredericksburg died down, the air was filled with the screams of hundreds of wounded men and horses. Dry sage grass around them caught fire and burned many men alive.

Marye's Heights

Over on the northern end of the battlefield, Brig. Gen. William French's division of II Corps prepared to move forward, subjected to Confederate artillery fire descending on the fog-covered city of Fredericksburg. General Burnside's orders to Maj Gen Edwin Sumner, commander of the Right Grand Division, was to send "a division or more" to seize the high ground west of the city, assuming that his assault on the southern end of the Confederate line would be the decisive action of the battle.

The avenue of approach to the Confederates was difficult, mostly open fields, but interrupted by scattered houses, fences, and gardens that would restrict the movement of the battle lines. A canal stood about 200 yards west of the town, crossed by three narrow bridges, which would require the Union troops to funnel themselves into columns before proceeding. About 600 yards west of Fredericksburg was a low ridge called Marye's Heights, rising 40-50 feet above the plain. Though known as Marye's Heights, it was composed of several hills, north to south: Taylor's, Stansbury, Marye's, and Willis Hill. Near the crest of the part of the ridge made of Marye's and Willis Hihll, a narrow lane in a slight cut, the Telegraph Road, known after the battle as the Sunken Road, was protected by a 4-foot stone wall, enhanced in places with log breastworks and batis, making it a perfect infantry defensive position.

Confederate Major General Lafayette McLaws initially had about 2000 men on the front line of Marye's Heights, and there were an additional 7000 men in reserve on the crest and behind the ridge. Massed artillery also provided almost uninterrupted coverage of the plain below. General Longstreet was assured by his artillery commander, Lt Col Edward P Alexander, "General, we cover that ground now so well that we will comb it as with a fine-tooth comb. A chicken could not live on that field when we open on it."

The Confederate troops behind the stone wall

The fog lifted from the town about 10 AM, and Sumner gave his order to advance an hour later. French's brigade under Brig. Gen. Nathan Kimball began to move around noon. They advanced slowly through heavy artillery fire, crossed the canal in columns over the narrow bridges, and formed in line, with fixed bayonets, behind the protection of a shallow bluff. In perfect line of battle, they advanced up the muddy slope until they were cut down about 125 yards from the stone wall by repeated rifle volleys.

Some soldiers were able to get as close as 40 yards, but having suffered severe casualties from both artillery and infantry fire, the survivors clung to the ground. Kimball himself was severely wounded during the assault, and his brigade suffered 25% casualties. French's brigades under Col John Andrews and Col Oliver Palmer followed, with casualty rates of about 50%.

Sumner's original order called for the division of Brig. Gen. Winfield Hancock to support French and Hancock sent forward his brigade under Col Samuel Zook, behind Palmer's. They met a similar fate. Next was his Irish Brigade under Brig. Gen. Thomas Meagher.

Union Irish Brigade, which participated in the fighting at Marye's Heights.

Irish Regiment Flag

The original flag flown at Fredericksburg hangs in the Museum of the Confederacy

First Scottish Regiment Flag

This is the flag flown at Fredericksburg, not the Second Scottish Regiment Flag, which was introduced in 1864.

By coincidence, they attacked the area defended by fellow Irishmen of Col. Robert McMillan's 24th GA Infantry. One Confederate who spotted the green regimental flags approaching cried out, "Oh, God what a pity! Here comes Meagher's fellows." But McMillan exhorted his troops, "Give it to them now, boys! Now's the time! Give it to them!"

Hancock's final brigade was led by Brig. Gen. John Caldwell. Leading his two regiments on the left, Col Nelson Miles suggested to Caldwell that the practice of marching in formation, firing, and stopping to reload made the Union soldiers easy targets, and that a concerted bayonet charge might be more effective in carrying the works. Caldwell denied permission; Miles was struck by a bullet in the throat as he led his men to within 40 yards of the wall, where they were pinned down as their predecessors had been. Caldwell himself was soon struck by two bullets and put out of the action.

Union Assault on Marye's Heights

The commander of the II Corps, Maj. Gen. Darius Couch, was dismayed at the carnage wrought upon his two divisions in the hour of fighting, and like Col. Miles, realized the tactics weren't working. He first considered a massive bayonet charge, but as he surveyed the front, he quickly realized French's and Hancock's divisions were in no shape to move forward again.

He planned for his final division, under Maj. Gen. Oliver Howard, to swing to the right and attempt to envelop the Confederate left, but after receiving urgent requests for help from French and Hancock, he sent Howard's men over and around the fallen troops instead. The brigade of Col. Joshua Owen went in first, reinforced by Col. Norman Hall's brigade, and then two regiments of Brig. Gen. Alfred Sully's brigade. The other corps in Sumner's grand division was the IX Corps, and he sent in one of its divisions under Brig. Gen. Samuel Sturgis. After two hours of desperate fighting, four Union divisions had failed in the mission Burnside originally assigned to one. Their casualties were heavy - II Corps lost 4398 and Sturgis's division 1033.

While the Union army paused, Longstreet reinforced his line so that there were four ranks of infantrymen behind the stone wall. Brig. Gen. Thomas Cobb of Georgia, who commanded the key sector of the line was mortally wounded by an exploding artillery shell, and was replaced by Brig. Gen. Joseph Kershaw. General Lee expressed some concern to Longstreet about the massing troops breaking the line, but Longstreet assured him, "General, if you put every man on the other side of the Potomac on that field to approach me over the same line, and give me plenty of ammunition, I will kill them all before they reach my line."

By midafternoon, Burnside had failed on both flanks to make progress against the Confederates. Rather than reconsidering his approach in the face of such heavy casualties, he decided to continue on the same path. He sent orders to Franklin to renew the assault on the left (orders he ignored), and ordered his Center Grand Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, to cross the Rappahannock into Fredericksburg and continue the attack on Marye's Heights. Hooker performed personal reconnaissance (something neither Burnside nor Sumner did) and returned to Burnside's HQ to advise against the attack.

Brig Gen. Daniel Butterfield, commanding Hooker's V Corps sent his division under Brig. Gen. Charles Griffin to relieve Sturgis's men while waiting for Hooker to return from his conference with Burnside. By this time, Maj. Gen. George Pickett's Confederate division and one of Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood's brigades had marched north to reinforce Marye's Heights. Griffin smashed his three brigades against the Confederate position, one by one. Also concerned about Sturgis, Couch sent the six guns of Capt. John Hazard's Battery B, 1st Rhode Island Light Artillery, to within 150 yards of the Confederate line. They were hit hard by Confederate sharpshooters and artillery fire and provided no effective relief to Sturgis.

A soldier in Hancock's division reported movement in the Confederate line, leading some to believe they might be retreating. Despite the unlikeliness of that belief, the V Corps division of Brig. Gen. Andrew Humphreys was ordered to attack and capitalize on the situation. Humphreys led his first brigade on horseback, with his men moving over and around fallen troops with fixed bayonets and unloaded rifles; some of the fallen men clutched the passing pant legs, urging their comrades not to go forward, causing the brigade to become disorganized in their advance. The charge reached to within 50 yards before being cut down by rifle fire. Brig. Gen. George Sykes was ordered to move forward with his V Corps regular army division to support Humphreys's retreat, but his men were caught in a crossfire and pinned down.

By 4 PM, Hooker returned from his meeting with Burnside, having failed to convince the general to abandon his attacks. While Humphreys was still attacking, Hooker reluctantly ordered the IX Corps division of Brig. Gen. George Getty to attack as well, but this time to the leftmost portion of Marye's Heights, called Willis Hill. Col. Rush Hawkins's Brigade, followed by Col Edward Harland's brigade, moved along an unfinished railroad line just north of Hazel Run, approaching close to the Confederate line without detection in the gathering twilight, but they were eventually detected, fired on, and repulsed.

Seven Union divisions had been sent in, generally one brigade at a time, for a total of fourteen separate charges, all of which failed, costing between 7,000 and 9,000 casualties. Confederate losses at Marye's Heights totaled around 1200. The setting sun and the please of Burnside's subordinates were enough to put an end to the attacks. Longstreet later wrote, "The charges had been desperate and bloody, but utterly hopeless." Thousands of Union soldiers spent the cold December night on the fields leading to the heights, unable to move or assist the wounded because of Confederate fire. That night, Burnside attempted to blame his subordinates for the disastrous attacks, but they argued it was entirely his fault and none other's.

During a dinner meeting in the evening of December 13, Union General Burnside dramatically announced he would personally lead his old IX Corps in one final attack on Marye's Heights, but his generals talked him out of it the next morning. The armies remained in position throughout the day on December 14th. That afternoon, Burnside asked Lee for a truce to attend to his wounded, which Lee graciously granted. Both sides removed their wounded, and the next day, the Federal forces retreated across the river, and the campaign came to an end.

Union casualties were 14,199, with 2,384 killed, the rest wounded (9600) or captured/missing. They lost two generals - Brig. Gens. George Bayard and Conrad Jackson. The Confederates lost 5180 (550 killed, 4108 wounded, the rest captured/missing). Brig. Gens. Maxcy Gregg and T.R.R. Cobb were wounded but would recover.

Angel of Marye's Heights, Sgt. Richard Rowland Kirkland

One of the more courageous acts of the entire war, and a sample of the humanity sometimes lacking in war, was the story of Confederate Sergeant Richard Rowland, Kirkland, of Company G, 2nd South Carolina Volunteer Infantry. He had been stationed at a stone wall by the sunken road below Marye's Heights.

The Stone Wall and Sunken Road, 2010;

Sharpsburg Confederate Memorial Battlefield Park

He had a close-up view to the suffering, and like so many others was appalled at the cries for help of the Union wounded throughout the cold winter night of December 13, 1862. After getting the permission of his commander, Brig. Gen. Joseph Kershaw, Kirkland gathered canteens, and in broad daylight, without the benefit of a recognized ceasefire or flag of truce, provided water to numerous Union wounded lying on the field of battle, easing their suffering and cries.

Memorial Statue of Sgt. Kirkland, a copy of the original at Fredericksburg Battlefield Park.

Flat Rock, South Carolina

Union soldiers held their fire, as it was obvious what his intent was. Kirkland was nicknamed the "Angel of Marye's Heights" for his actions, and is memorialized with a statue by Anton van der Velden at the Fredericksburg Confederate Memorial Battlefield Park where he carried out his actions, and later copied in his home town of Flat Rock, South Carolina.

On the night of December 14, the Aurora Borealis made an appearance, unusually enough for the latitude, possibly caused by a solar flare. One witness described it as "the wonderful spectacle of the Aurora Borealis was seen in the Gulf States. The whole sky was a ruddy glow as if from an enormous conflagration, but marked by the darting rays peculiar to the Northern light."

The remarkable event was noted in the diaries and letters of many of the Union and Confederate soldiers at Fredericksburg, such as John W. Thompson, Jr, who wrote: "Louisiana sent those famous cosmopolitan Zouaves called the Louisiana Tigers, and there were Florida troops who, undismayed in fire, stampeded the night after Fredericksburg, when the Aurora Borealis snapped and crackled over that field of the frozen dead hard by the Rappahannock ..."

Some of the senior Confederate generals took it as a sign from heaven of the blessing of their cause; some Union troops took it as a divine shield of protection over the Confederates.

Lull and Withdrawal

Union View of the Confederates, one of the rare times they photographed their opponents during the War for Southern Independence

General Burnside and the Federal troops had abandoned the once beautiful city of Fredericksburg. A chilling rainstorm drenched the night countryside as the Federal troops retreated across the Rappahannock. After they left, General Jackson looked over the still bloody battlefield and declared, "I did not think a little red earth would have frightened them. I am sorry that they are gone." By the 16th, Confederate troops reoccupied Fredericksburg. Later as Jackson and his staff rode through the city their anger was aroused by the extent of the ruthless vandalism. A staff officer commented on how thoroughly the Federals had taken the town apart and asked, "What can we do?" "Do?" replied Jackson, "Why, shoot them!"

On Princess Anne Street General Jackson is directing the refortification of the city and setting up new defenses, as a horse-drawn artillery piece rushes by, pulled by a fine team of Morgan horses. Soon new orders will call Jackson away from the city he helped to defend so successfully.

The people of Fredericksburg welcomed the Confederates as liberators from the Union looters, and the troops were refreshed, as they helped repair and clean the city.

Aftermath of the Battle

The South was jubilant over their victory. The Richmond Examiner described it as "a stunning defeat to the invader, a splendid victory to the defender of the sacred soil." General Lee, normally reserved, was described by the Charleston Mercury as "jubilant, almost off-balance, and seemingly desirous of embracing everyone who calls on him." The newspaper also exclaimed that, "General Lee knows his business and the army has yet known no such word as fail."

Reactions were the opposite in the North, and both the Army and President Lincoln came under strong attacks from both politicians and the press. The Cincinnati Commercial wrote, "It can hardly be in human nature for men to show more valor or generals to manifest less judgment, than were perceptible on our side that day." Senator Zachariah Chandler, a radial Republican, wrote, "The President is a weak man, too weak for the occasion, and those fool or traitor generals are wasting time and yet more precious blood in indecisive battles and delays." Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin visited the White House after a trip to the battlefield. He told the President, "It was not a battle, it was butchery."

Curtin reported that the President was "heart-broken at the recital, and soon reached a state of nervous excitement bordering on insanity." Lincoln himself wrote, "If there is a worse place than hell, I am in it." Burnside was relieved of command a month later, following an unsuccessful attempt to purge some of his subordinates from the Army, and the humiliating failure of his Mud March in January.

Christmas in Fredericksburg

Time was short for General Jackson's Stonewall Brigade; final preparations were underway. He had received orders from General Lee to move his corps east, from the Shenandoah towards the Rappahannock River. The Federal army under the command of General Burnside was gathering in great numbers across the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg in an attempt to sweep around Lee's eastern flank and attack Richmond.

Jackson's corps numbered over 38,000 soldiers, the largest command he had ever had. Among these troops were his old reliable, tried and true, Stonewall Brigade, also referred to informally as "Virginia's First Brigade." Organized and trained personally by Jackson at Harper's Ferry in April 1861, the brigade would distinguish itself at the Battle of First Manassas, and become one of the most famous combat units in the war.

Snow lay on the ground in Winchester at the Frederick County Courthouse as new volunteers were organized and drilled for their march to meet the enemy. A young soldier was given a Christmas gift made by his sweetheart. Like so many couples, they did not know what the future held. The town was grateful to the Confederate soldiers for freeing them from the Union troops who had only recently been there.

A Winchester resident watching the men pass through the town remarked how poor looking the soldiers were. "They were very destitute, many without shoes, and all without overcoats or gloves, although the weather was freezing. Their poor hands looked so red and cold holding their muskets in the biting wind....They did not, however look dejected, but went their way right joyfully."

While foreign shipments came in, and cotton went out, just at reduced levels from prewar standards, supply issues within the Confederacy meant that sometimes soldiers were not always equipped as well as their Union counterparts. Before the next battle, these new recruits would have new boots to cover their feet from the cold, and new overcoats woven in the United Kingdom. Still, the British had not recognized the Confederates, nor had they broken their neutrality of trading with both North and South, but refused to trade munitions with either side.

Last edited:

![300px-CSSShenandoah[1].jpg 300px-CSSShenandoah[1].jpg](https://www.alternatehistory.com/forum/data/attachments/381/381213-710f472a39c64f2391e5461dacc100fa.jpg)