Franklin Pierce is one of the more interesting figures of the mid-19th century. After Andrew Jackson left office in 1837, he was succeeded by a series of presidents who have largely been forgotten by the public. And while Pierce was no Washington, Jefferson, or Jackson, he certainly made his mark on American history. He entered the presidency at a time when America was increasingly divided, and through his leadership prevented those divisions from tearing the nation apart. Ever since he left office, he has been praised for his actions as president. However, more recent historians are divided on the legacy of Franklin Pierce. Some praise his leadership abilities and willingness to compromise for the good of his country. Others take a more critical view. Critical historians portray him as a warmonger and a man who had no conscience when it came to issues like slavery. Here the reader will simply find a presentation of the facts, and is free to come to his or her own conclusions.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Man of the Hour, A Franklin Pierce Story

- Thread starter CELTICEMPIRE

- Start date

Chapter I, The First Two Years

The founding fathers united the states in 1787, but in the decades that followed, their work was coming undone. Despite their great wisdom, the Constitution they wrote had failed to resolve one issue that would soon surpass all others in importance. The issue of slavery was set aside, to be revisited at a future date. In all fairness, at the time it appeared that slavery was going to eventually die out. In the 19th century it became apparent that slaveholders were not going to surrender their precious institution easily. As slavery largely disappeared from the North, it became even more entrenched in the South. This created a geographic polarization. This polarization was exacerbated by recent expansion at the expense of Mexico. Making matters worse was the increasing talk of secession, mostly in the South, though most saw this as bluffing. This made it all the more important that the Democrats choose a man who could appeal to both regions of an increasingly divided nation. In 1852 that man was Franklin Pierce.

Franklin Pierce (D-NH)/William King (D-AL): 1,605,943 Votes (50.83%), 254 Electoral Votes

Winfield Scott (W-NJ)/William Graham (W-NC): 1,386,418 Votes (43.88%), 42 Electoral Votes

John Hale (FS-NH)/George Julian (FS:-IN): 155,799 Votes (4.93%), 0 Electoral Votes

Others [1]: 11,480 Votes (0.36%), 0 Electoral Votes

Franklin Pierce was a Mexican War veteran and exceedingly popular in both the North and the South. He was thus the perfect candidate for the nomination. He would go on to win the election in a landslide, defeating Whig candidate Winfield Scott by nearly seven percent. He won 254 electoral votes to Scott’s 42. Pierce’s support came from both North and South, and so did Scott’s. Of the four states that voted against Pierce, two were Northern and two were Southern. It looked as if the sectional divisions threatening to tear the country apart might subside. That would be wishful thinking, of course. But plenty of people in both sections were optimistic. The Pierce presidency, interestingly enough, almost didn’t happen. On January 8, 1853, in Amherst, Massachusetts, there was a train accident. Aboard the train was Pierce, his wife, and his son. Fortunately, no one was killed [2]. In his inaugural address, which he gave from memory, he spoke in favor of peace but also in favor of expansion. He never mentioned the issue of slavery.

(Franlin's wife, Jane, and his son, Benjamin)

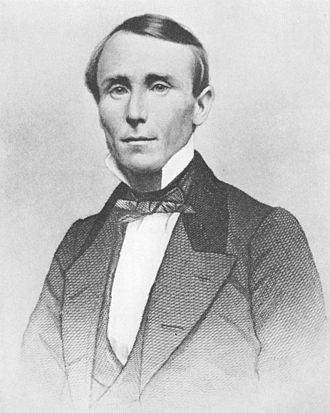

Pierce’s cabinet would include Democrats from all around the nation. His Vice President was the 66-year-old Alabama Senator William R. King. King held a firm pro-slavery stance. His Secretary of State was William Marcy of New York, who had served as Secretary of War under James K. Polk. Marcy was a committed expansionist. Pierce appointed James Guthrie of Kentucky, an opponent of central banking, as Secretary of the Treasury. Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, advocate of slavery and expansionism, was chosen as Secretary of War. Justice Caleb Cushing of Massachusetts, a Northerner with southern sympathies, was chosen as Attorney General. Pennsylvania Attorney General James Campbell became the new Postmaster General, the first Catholic member of a presidential candidate. The new Secretary of the Navy would be former Representative James C. Dobbin of North Carolina, an advocate of a strong navy. Michigan Governor Robert McClelland, a moderate on slavery, was selected as Secretary of the Interior. Pierce would soon appoint John A. Campbell of Alabama, a staunchly pro-slavery justice, to the Supreme Court. On April 18, King died, and his position would remain vacant for the next four years.

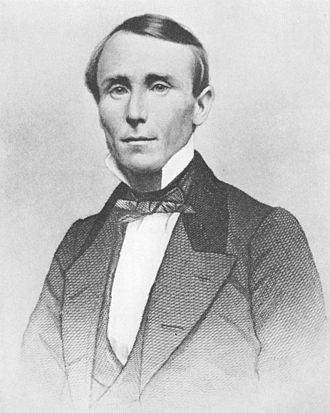

(William Rufus DeVane King, 1786-1853)

Pierce himself was an expansionist, and in late 1853 America purchased land from Mexico in what is known as the Gadsden purchase (named after South Carolina businessman and Ambassador James Gadsden). Commodore Matthew Perry went to Japan, and the Convention of Kanagawa was signed in 1854. America could now trade with Japan at the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate [3]. Back home, the early months of 1854 saw an attempt by Democratic Senators to repeal the Missouri Compromise. These Senators, led by Stephen Douglas, wanted to allow voters in the new territories determine whether their territory would be admitted as a slave state or a free state. This would open up the new territories of Kansas and Nebraska to the possibility of slavery. While support for such a bill was highest in the south, plenty of Northern senators supported it as well (Douglas himself was from Illinois). When they approached the president, they were unable to convince him to support their bill. Pierce argued with Southern senators, claiming that Kansas was “too cold” for slavery to work there, and that any attempt to bring slavery into Kansas would turn public opinion against the South. After hours of negotiations, Pierce was unmoved. He unequivocally stated that he would veto any attempt to allow slavery in Kansas.

(Japanese Depiction of Commodore Matthew C. Perry)

Pierce assured Southern political leaders that he would protect their interests in other ways. He suggested that he would support efforts to expand Southwards, particularly Cuba. He also pledged to support a southern route for the transcontinental railroad, using the land recently purchased from Mexico. And he told them he could sway enough Northern Democrats to vote for the admittance of New Mexico as a slave state in the near future. Nevertheless, many southerners were angry at the president. A rift between Pierce and Douglas occurred as well. Kansas, though not yet populous enough to attain statehood, was destined to become a free state. Despite this, the majority of settlers were from neighboring Missouri. The Kansas Territory, under Pierce’s appointed governor Andrew Reeder, would ban slavery while at the same time enforcing fugitive slave laws. There was a small but vocal abolitionist movement in the territory. Nebraska, on the other hand, would be mostly settled by people who were staunchly anti-slavery. Later that year, the Nebraska territory would see conflict between the US Army and the Brulé band of the Lakota.

(Stephen Douglas, advocate of popular sovereignty)

When Pierce began to push for a southern railroad, he predictably faced opposition from northerners. Ironically, much of the opposition came from Whigs, who were generally supportive of internal improvements. In addition, there were plenty of southerners who were disinterested in the railroad. Pierce changed tactics. He argued that the railroad was necessary for national security purposes. He claimed that a railroad from New Orleans to San Francisco would allow for the quick movement of troops, which could be useful in protecting settlers in the Southwest from attacks by hostile Indian tribes. In order to get some northern Whigs on board, the railroad bill was amended to include increased funding for infrastructure in the North, and stipulated that free labor would be used to build the railroad. Though the labor would “free,” it would hardly be fair to the Chinese and Irish immigrants who would do most of the work. James Gadsden helped convince some southerners who were still on the fence. The bill was narrowly wrangled through congress and signed by President Franklin Pierce on August 1, 1854.

(James Gadsden was the brains behind the Southern railroad)

The issue of slavery would continue to threaten disunion. Pierce’s administration was committed to enforcement of the fugitive slave act. Federal agents snatched escaped slaves from Massachusetts, horrifying many Northerners. This helped grow the Free-Soil Party and forced Northern Whigs to take a firmer stance against slavery. During the 1854 congressional elections, Northern Whigs used both anti-slavery and anti-immigrant sentiment against the Democratic Party. Democrats experienced losses in both the House and the Senate, mostly in the North. Nevertheless, both chambers maintained their Democratic majorities. Linn Boyd of Kentucky kept his position as House Speaker. The 34th Congress would have 124 Democratic Representatives, 105 Whigs, and 5 Free-Soil Representatives. The President pro tempore of the Senate would be Lewis Cass of Michigan. The Democratic majority fell from 35 to 33 Senators. There were 27 Whig and 2 Free Soil Senators. There was a great deal of infighting in both parties during the congressional elections, which was seen as a sign of things to come.

(House Speaker Linn Boyd)

2: This is the POD, in OTL Benjamin Pierce was killed in that accident.

3: Up to this point all the domestic and foreign policies of the Pierce administration are the same as OTL.

Awesome! It's an interesting change to see Pierce actually manage to be a not totally inept president.

Glad to have you on board!

Having a well-regarded Pierce Presidency is an interesting premise. I look forward to your future updates.

Will the epic bromance between Pierce and Davis be the focus early on? Davis for VP in 1856?

Will the epic bromance between Pierce and Davis be the focus early on? Davis for VP in 1856?

Having a well-regarded Pierce Presidency is an interesting premise. I look forward to your future updates.

Will the epic bromance between Pierce and Davis be the focus early on? Davis for VP in 1856?

Wait and see

Kennedy4Ever

Banned

Alright!! So excited for this timeline! I can already tell it’s going to be a good one!

A TL centered on one of the forgotten blunder Presidents of the 1850s. Interesting.

What will posting schedule look like?

Probably once a week, I plan on having the next post up by Sunday night. I have a much more stable job now (when I was writing America's Silver Era I was working less than twenty hours a week on average, which gave me more time to write).

Chapter II, Nicaragua

Despite the best efforts of President Pierce, as well as many other Democrats and Whigs, slavery was the inescapable issue of the time. The last act of the outgoing 33rd Congress was to reduce tariffs. This was one of the most important issues dividing Democrats and Whigs in the past. Two decades earlier, the tariff issue had even threatened disunion. Franklin Pierce hoped that tariffs could once again become the dividing issue in politics. But by 1855 it ceased to be the polarizing issue it once was. Newspapers that favored the Whigs tried to excite passion over the tariff issue, hoping to reinforce partisan loyalty. They argued that the decrease in tariffs would destroy American industry. But the American public had largely forgotten about tariffs within a few months. While the citizens of New England were unhappy with Pierce’s free trade policies, they were more upset with the enforcement of fugitive slave laws.

(Railroad workers in Eastern Texas)

The Pierce administration turned its attention towards foreign affairs. For years Nicaragua had seen conflict between the elites of Leon (Democratic Party) and the elites of Granada (Legitimist Party), the latter of which ruled the country. The elites of Leon enlisted in support of their cause an American adventurer named William Walker. A series of victories in 1855 saw victory for the Democrats and Walker would become President of the nation the following year. Many, though not all, of the men who followed Walker desired to make Nicaragua an American slave state. Walker’s government had not gotten around to legalizing slavery yet (the institution had been abolished in 1824, shortly after independence). In May the Pierce administration recognized Walker’s government. But his control of the country was far from secure. Opposition within the country remained, and Walker’s Nicaragua had gone to war with Costa Rica a few months earlier. Walker called for help.

(William Walker)

Pierce was favorable to Walker’s plea for American troops. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis was particularly eager for America to get involved. Secretary of State William Marcy supported American intervention as well. The three all hoped for Nicaraguan statehood. While Davis hoped for annexation and statehood in the near future, Pierce and Marcy understood that the Central American country would need to be “Americanized” before attaining statehood. In June, Pierce spoke before congress, claiming that American citizens in Nicaragua were under threat from Costa Rica. He also argued that William Walker was bringing Republicanism and Constitutional government to the country. Pierce, against the advice of Davis, did not argue for annexation. Two major factors worked against Nicaraguan statehood. The first was that the country’s population was mostly Catholic and couldn’t speak English. The second was that Nicaragua was south of the Missouri Compromise line, making its admittance as a state unlikely to be widely supported in the North.

(The flag of Walker's Nicaragua)

In June, Pierce asked Congress for a declaration of war on Costa Rica. Most Democrats voted for the bill, while the Whigs were divided. The Free-Soil Party unequivocally opposed the war. The Declaration of War passed both houses of Congress by comfortable, though not commanding, margins. Five thousand soldiers would be deployed to Nicaragua. There was concern that other Central American countries would join Costa Rica against Walker’s government in Nicaragua. The presence of American soldiers in the country prevented this. America also blockaded Costa Rican ports. Other nations in the region accused America of engaging in Imperialism, and the British government denounced America’s actions. Some have speculated that the United States and Britain could have gone to war over Central America. As interesting as such speculations may be, they are outside the realm of plausibility.

Back home, Pierce was running for a second term. No one had succeeded in doing this since Andrew Jackson twenty-four years earlier. But Pierce thought he had what it took. His main challenger would be Illinois Senator Steven Douglas. Douglas advocated for popular sovereignty on slavery. This attracted support from many southerners who saw him as the final hope for Kansas being admitted as a slave state. There was also former Representative William Yancey of Alabama, who led the radical pro-slavery fire-eaters. Finally, there was the anti-slavery John C. Fremont of California. Douglas and Fremont both accused Pierce of using the war to increase his popularity at home. Yancey supported the war but also criticized Pierce for not immediately pushing for Nicaraguan statehood. Only Illinois and Missouri backed Douglas. Texas and Louisiana remained loyal to Pierce due to the railroad, and Jefferson Davis convinced Mississippi delegates to stick with the President. Yancey was supported by his home state of Alabama as well as a few delegates from Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida. Fremont only received scattered support across the Northeast.

Douglas urged his supporters to unite behind Pierce, and they mostly did. Quitman and Fremont would not endorse the Democratic ticket, however. The delegates at Cincinnati turned their attention towards selecting a Vice President. As Pierce was a Yankee, the ticket would need to be balanced with a southerner. Jefferson Davis hoped that he would be chosen to fill the vacancy that was left by the death of William King three years earlier. Pierce himself had told Davis that he would love to have him as his running mate. Former Representative Howell Cobb of Georgia was also a strong contender. But there was also another man, one who could appeal better to Northerners. This man was former President of Texas and current Senator Sam Houston. As an opponent of the expansion of slavery, delegates from the free states rallied behind him. On the second ballot, Houston won a majority. Davis was angry, but there was nothing he could do about it now.

(Sam Houston)

In 1855 the first tracks of the Trans-continental Railroad were laid down in New Orleans. Soon, the railway extended into Texas. The construction of the railroads was not without its own controversies, however. Some abolitionists claimed that the railroad was built to increase slave power and hand the West to the South. The state of California was a concern, and some claimed the railroad would put California under Southern influence, and might possibly lead to the legalization of slavery there. There was also an influx of foreign laborers into the small towns in Louisiana and Texas, mostly Irish. This led to an increase of nativist sentiment there. In some places there were violent confrontations between railroad workers and the locals. The same happened with Chinese laborers in San Francisco.

(Railroad workers in Eastern Texas)

The Pierce administration turned its attention towards foreign affairs. For years Nicaragua had seen conflict between the elites of Leon (Democratic Party) and the elites of Granada (Legitimist Party), the latter of which ruled the country. The elites of Leon enlisted in support of their cause an American adventurer named William Walker. A series of victories in 1855 saw victory for the Democrats and Walker would become President of the nation the following year. Many, though not all, of the men who followed Walker desired to make Nicaragua an American slave state. Walker’s government had not gotten around to legalizing slavery yet (the institution had been abolished in 1824, shortly after independence). In May the Pierce administration recognized Walker’s government. But his control of the country was far from secure. Opposition within the country remained, and Walker’s Nicaragua had gone to war with Costa Rica a few months earlier. Walker called for help.

(William Walker)

Pierce was favorable to Walker’s plea for American troops. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis was particularly eager for America to get involved. Secretary of State William Marcy supported American intervention as well. The three all hoped for Nicaraguan statehood. While Davis hoped for annexation and statehood in the near future, Pierce and Marcy understood that the Central American country would need to be “Americanized” before attaining statehood. In June, Pierce spoke before congress, claiming that American citizens in Nicaragua were under threat from Costa Rica. He also argued that William Walker was bringing Republicanism and Constitutional government to the country. Pierce, against the advice of Davis, did not argue for annexation. Two major factors worked against Nicaraguan statehood. The first was that the country’s population was mostly Catholic and couldn’t speak English. The second was that Nicaragua was south of the Missouri Compromise line, making its admittance as a state unlikely to be widely supported in the North.

(The flag of Walker's Nicaragua)

In June, Pierce asked Congress for a declaration of war on Costa Rica. Most Democrats voted for the bill, while the Whigs were divided. The Free-Soil Party unequivocally opposed the war. The Declaration of War passed both houses of Congress by comfortable, though not commanding, margins. Five thousand soldiers would be deployed to Nicaragua. There was concern that other Central American countries would join Costa Rica against Walker’s government in Nicaragua. The presence of American soldiers in the country prevented this. America also blockaded Costa Rican ports. Other nations in the region accused America of engaging in Imperialism, and the British government denounced America’s actions. Some have speculated that the United States and Britain could have gone to war over Central America. As interesting as such speculations may be, they are outside the realm of plausibility.

Back home, Pierce was running for a second term. No one had succeeded in doing this since Andrew Jackson twenty-four years earlier. But Pierce thought he had what it took. His main challenger would be Illinois Senator Steven Douglas. Douglas advocated for popular sovereignty on slavery. This attracted support from many southerners who saw him as the final hope for Kansas being admitted as a slave state. There was also former Representative William Yancey of Alabama, who led the radical pro-slavery fire-eaters. Finally, there was the anti-slavery John C. Fremont of California. Douglas and Fremont both accused Pierce of using the war to increase his popularity at home. Yancey supported the war but also criticized Pierce for not immediately pushing for Nicaraguan statehood. Only Illinois and Missouri backed Douglas. Texas and Louisiana remained loyal to Pierce due to the railroad, and Jefferson Davis convinced Mississippi delegates to stick with the President. Yancey was supported by his home state of Alabama as well as a few delegates from Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida. Fremont only received scattered support across the Northeast.

Douglas urged his supporters to unite behind Pierce, and they mostly did. Quitman and Fremont would not endorse the Democratic ticket, however. The delegates at Cincinnati turned their attention towards selecting a Vice President. As Pierce was a Yankee, the ticket would need to be balanced with a southerner. Jefferson Davis hoped that he would be chosen to fill the vacancy that was left by the death of William King three years earlier. Pierce himself had told Davis that he would love to have him as his running mate. Former Representative Howell Cobb of Georgia was also a strong contender. But there was also another man, one who could appeal better to Northerners. This man was former President of Texas and current Senator Sam Houston. As an opponent of the expansion of slavery, delegates from the free states rallied behind him. On the second ballot, Houston won a majority. Davis was angry, but there was nothing he could do about it now.

(Sam Houston)

Well, you got to the divergence fast. It'll be interesting to see how the Nicaragua stuff plays out down the line, in what I'm assuming will be Pierce's second term.

Pierce-Houston?

Wow!

Bit of a blow to Davis but even giving him the SoS position in the next administration would place him as the "heir" might soften up his anger a bit.

Wow!

Bit of a blow to Davis but even giving him the SoS position in the next administration would place him as the "heir" might soften up his anger a bit.

Share: