Those communications certainly existed, but to my knowledge no direct connections, especially for telephone, existed between CONUS and Puerto Rico for some time. I also find the whole point about communications as being hollow; I can send a message to someone in China today and vice versa, that does not mean assimilation is occurring.

That's the point.

@interpoltomo argued that Puerto Rico did not assimilate because, in part, it was more isolated from the United States than Mexico would have been; I was demonstrating that this is not true. You are merely adding additional evidence that isolation is not really such an important factor.

Not really; Washington D.C. is almost 2,000 miles from Puerto Rico while by the dawn of the 20th Century you could generally get just about anywhere in the U.S. within three days thanks to railroads.

And you can sail 2000 miles in 6 days at 12 knots, which isn't a particularly fast cruise; the point is that Puerto Rico was approximately as difficult to reach as many other places in the country, especially somewhat remote areas such as mountainous areas in the Mountain West, which were nevertheless completely Anglicized in a linguistic sense. This indicates that a large native population of Hispanophones is not so trivial to Anglicize.

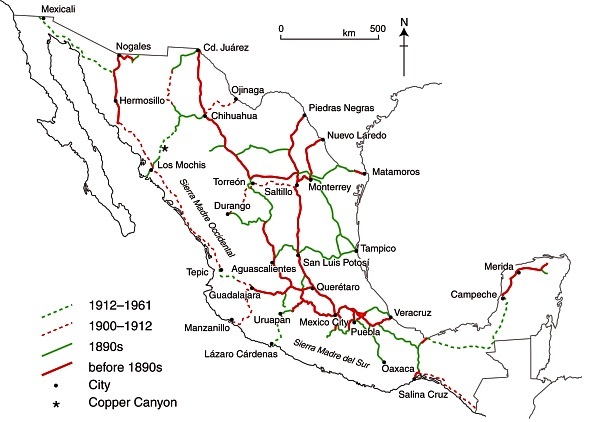

An annexed Mexico would have direct land connections

Remember that a considerable portion of northern Mexico is relatively empty desert or mountains. In practice, the main connections between the United States and central and southern Mexico for some time are likely to be by sea; those areas will probably be very much like islands in many respects.

EDIT: Also, given available technology in 1848 it will take much longer for people to reach the central or southern Mexico overland than via sea travel; rather longer than it took to reach Puerto Rico from the United States in 1898, for sure.

and more active interactions the Anglophone population of the U.S. particularly as a result of migration from the Southern states. It also would be directly tied into the political structure of the U.S. in a way Mexico never has been.

Sure, I just question how significant all of these factors would actually be in driving the abandonment of the Spanish language in favor of English. They might drive bilingualism, but that's not at all the same thing as the claim that Mexico would become mostly English-speaking.

Your post was unclear, my apologies.

Again, you were very unclear on this:

The relevant bits:

Yes, I read the material you're quoting. It explains how being a commonwealth gives Puerto Rico more autonomy

than it would have as a territory, which I already knew. It does not explain how it has more autonomy

than it would have as a state, which was the assertion

@interpoltomo made, which I very specifically and repeatedly said was what I was talking about in the material you quoted:

I don't see how a commonwealth is "more autonomous" than a state, anyway.

What I do not see, and what that link does not indicate, is how being a territory of the United States ultimately subject to Congressional control gives Puerto Rico more autonomy than being a state would

So it does not really seem to me that the Commonwealth could have had any significant effect on Puerto Rican ability to resist or forestall assimilation, because while they were a territory they certainly were not more autonomous than any state.

I can literally, for example, replace every single instance of the term "Puerto Rico" and "insular" in the other material you quote with the word "state" and it's still entirely true or favors states as being more autonomous:

Under this arrangement, the [state's] electorate selects its own government, and its representatives pass its own laws. [The state's] elected governor appoints all cabinet officials and other key members of the executive branch [actually in most cases states elect some of these as well, but that's merely a matter of the state constitution]; the [state] legislature determines the government’s budget; and the judicial system amends its civil and criminal code, without federal interference—as long as such measures do not contradict the US Constitution, laws, and regulations. [in fact, for states Congress itself can't do this, so this is one point where the Commonwealth has less autonomy than states]

By contrast, the limitations outlined in the next paragraph mostly do

not apply to states:

Under Commonwealth status, Puerto Rico continued to be an “unincorporated territory” that “belonged to but was not a part of the United States.” The US Congress and president could unilaterally dictate policy relating to defense, international relations, foreign trade, and investment. [Of course states also lack these powers, but they do have some influence over foreign trade and investment through such measures as governor visits to foreign countries] Congress could also revoke any insular law inconsistent with the US Constitution. [This is impossible with states; only courts have the right to review state statutes for consistency with the Constitution] Moreover, Congress or the president could apply federal regulations selectively to Puerto Rico, resulting in both concessions and revocations of special privileges. [This is also true for states; look at how many states got waivers for portions of No Child Left Behind, for example] In addition, many US constitutional provisions—such as the requirement of indictment by grand jury, trial by jury in common law cases, and the right to confrontation of witnesses—were not extended to the Commonwealth. [I suppose you could argue that this gives them some additional autonomy, just not anything you'd like to them to actually exert]

Again, Congress can't simply pass a law to establish an unelected commission to run any

state's budget the way they can and has done to Puerto Rico, which is a major indication that being a Commonwealth makes Puerto Rico

less autonomous than states, not

more; it has

less ability to run its own affairs without the specter of Congress coming in at any moment and changing things up, which is pretty much the definition of autonomy.

Meanwhile, the third paragraph could equally well be true of a state; in fact, the state of Texas meets many of those criteria, such as having a defined territory, history, and language (languages, in Texas' case; English is the main language of Texas, of course, but Spanish is far too historically important and well-used along the border to be left out). It has its own flag, the Lone Star Flag, and its own anthem, "Texas, Our Texas"; it has heroes like Davy Crockett or Sam Houston that kids learn about in school and rituals like the state pledge; it has its own university systems (plural!), museums, libraries, and other institutions; and its own traditions in literature and art, although I'll grant that many of these share great commonalities with neighboring literatures in the South, Mexico, and the Plains states. Unlike some other states, perhaps, there are many inhabitants of Texas who strongly identify with being Texan, along with or even perhaps in some cases before being American, so it also has a national population. It only lacks independent representation in sports and beauty contests. So unless you think independent participation in the Olympics and Miss World is a major sign of autonomy, I don't see how this is relevant.

Before becoming a Commonwealth it was an unincorporated territory, which in of itself was a special designation.

It was special alright, but

@interpoltomo's argument was that Puerto Rico was partially protected from assimilation by virtue of being more autonomous than states, and the entire point of designating it an unincorporated territory was so that the federal government could treat it as being

less autonomous, or at least equal, than other parts of the United States. So I don't see how the special status of pre-Commonwealth Puerto Rico supports the argument that having greater autonomy that it would have as a state played an important role in preserving the dominance of the Spanish language in Puerto Rico.

Despite this loose political relationship and and sheer isolation from the U.S. roughly a fourth of the population still speaks English fluently and 70% overall at least speak some.

I am skeptical that central and southern Mexico will become primarily English speaking--that is to say, regions where English is the usual first language--not that Mexico might become bilingual to some greater or lesser extent, so this statistic means nothing. And, again, Puerto Rico is

not isolated from the United States, and hasn't been at any point during the time it's been part of the United States, and it does

not have a loose political relationship with the United States, and certainly didn't before 1950!